5 America Votes or the Culture Industry

In the United States of America, voting is sacred. We connect all democracy to the act of voting (see Box 1). From voting for our representatives to making decisions on a microlevel, we ask people what they want to do, and generally, the majority wins.

Reality TV counts on our votes too. American Idol, America’s Got Talent, and The Voice depend on at home audiences to vote. When judges reference the voting, they say “America voted.” Even on shows like Survivor, contestants vote to see who should be eliminated from the show each week.

But reality TV shows do not have to follow “America’s” votes. In the contract for The Voice, producers state that they can change the voting results for programming purposes. I ran into this in my own research as one contestant informed me, they were eliminated after refusing to sign a contract.[1]

Even the idea of voting is problematic. To vote on American Idol, audience members need to have an internet-enabled device and each person can vote up to 10 times.

While American Idol clearly is not representative of the American public, the question of voting is always close by in all popular culture consumption. What counts as voting? Do dollars equal votes? These are questions for both popular culture and American society.

A critical approach to popular culture shows the issues of how money is the end goal of the entertainment industry, or culture industry as discussed below.

Consumption

Instead of saying people watch, listen to, read, and/or play popular culture, we usually reference popular culture consumption. We consume popular culture making us popular culture consumers. In American society, it is typical to see oneself as a consumer before other identities. Any time there is a boycott or a buycott, people place their identity as consumers ahead of their identities as citizens or residents. This framing is important because it links one’s position in society to the amount of money one possesses. At its root, consumption places the values of capitalism before all else. What does it mean to consume? What does it mean to be a consumer?

Consumption does not happen as a direct result of production. If it did, there would be no need for advertising/marketing. When someone releases a product without marketing, then no one will know the product exists. The average film producer spends over 50% the production costs on marketing for a film. This means that if a film cost $100 million to shoot, the producer will spend at least $50 million on marketing. People have some agency in their choices—meaning they can choose to watch a film or not—but without the marketing budget, no one will know it exists. The same could be said for the infinite number of great local bands stuck at local bars and regional tours.

In classical economics, first, “consumption usually refers to the purchase of a product and its exchange-value, or ‘price.’”[2] The focus is on exchange—you consume when you pay for something. Second, it refers to final consumption. When a good can no longer be used, it has been consumed—examples, eating something or a service. Another way to conceive of consumption is associated with waste—i.e., a fire consumes a house.

In my own work, I show how problematic it is to discuss “consuming” music, video games, movies, TV shows, etc.[3] For example, if we discuss file-sharing music, music neither has an exchange-value nor does it get used up. Or, if I watch a television show on a broadcast network, I do not pay to watch it, and my watching it does not preclude others from watching it.

Framing popular culture in terms of consumption places it within a specific set of economic interests. As a result, we think about popular culture that “sells.” This means that popular culture fans with more money have a greater say in what gets produced.

The music industry sharply demonstrates this phenomenon with how they calculate the popularity of a song. If a song is popular with poor people and rich people hate the song, then it will not be valued by the music industry. Billboard Magazine makes the charts of the most popular music via streams, sales, and radio airplay. A sale of music is clear in the rankings, but the other sources seem less like consumption.

For instance, Nielsen SoundScan tracks music “sales” by giving streaming from subscription services more weight than ad-supported or video streaming services (like YouTube). NBA YoungBoy is the top YouTube artist, but often lags behind on the Billboard charts because Nielsen SoundScan excludes many of the streams. That means that not all listens are equal.

This is not a new process, either. Tape cassettes provided youth with a way to create their own playlists by taping the radio, vinyl records, or other tapes. It created mix-tape culture, especially among hip-hop, punk, and electronic dance music subcultures.[4] This mixing and remixing provided a new way of listening that was completely untracked by the recording industry, partly because it was unprofitable for them. Record labels stuck to tracking listeners by tracking consumption either in record stores or through radio airplay.

When corporations in the culture industry track consumption of popular culture, they do so to place consumers over popular culture listeners, viewers, and participants. Those who spend more on popular culture (i.e., have expendable income) count more. Popular culture corporations produce products for wealthy consumers instead of creating popular culture based on actual demand. By tracking consumption, corporations ensure only the tastes of people with money count.

Critical Theory

The social system we have at any given moment is the product of relationships between people. Critical theory looks at how power operates within society to create and maintain the social system. Popular culture has been a major site of analysis for critical theory because it helps the powerful maintain their position in society.

Foundations

Critical theory emerged from the work of Karl Marx (1818-1883). Marx showed that society works through contradictions using a philosophical tool known as a dialectic. A dialectic shows that concepts are constituted by their negation (opposite). While the dialectic has existed since at least Plato in Ancient Greece, Marx uses the tool as outlined by German Philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Every order (thesis) contains its negation (antithesis), these contradictions resolve themselves in a new order (synthesis). It is Marx’s use of dialectic thinking that gave rise to critical theory because the method shows the constitution of power in society.

Marx showed that contradictions in society stemmed from class conflict. He called his method of analyzing class conflict over time “historical materialism.” During each era, classes come into conflict and bring about a new era giving rise to a new class conflict—i.e., historical materialism uses a dialectic approach to history. Our social order, Capitalism, is the conflict between capitalist and labor classes. They are dialectic in that they only exist in contradiction to each other.

Capitalism is a social order characterized by the endless accumulation of capital. Capital is a social relationship that congeals value created by workers in commodities. Capitalists own the means of production (the materials, machinery, and money used to produce commodities) and require workers to extract value (Labor Theory of Value discussed below). Labor itself is a commodity bought and sold by capitalists and labor’s use is to produce and sell commodities. Capitalists redeploy capital to earn more capital. Capitalists and workermeans of productions require each other to exist in capitalism as a social order. This was Marx’s major contribution to scholarship describing how capitalism works in Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume I-III.

Ideology

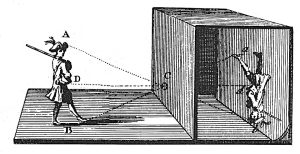

In another important thread from his work “The German Ideology,” Marx described the way powerful people in the ruling class maintain and expand their power. They do so through ideology. Ideology is an upside-down vision of reality that makes common sense to us, but perpetuates the position of the ruling class, what Marx describes as a camera obscura. A camera obscura is a dark box with a pinhole. The pinhole would project an image of the outside world on a wall, but the image would be inverted. This would allow a painter to quickly sketch the outside world upside-down. Ideology works the same way by showing the social world as the opposite from reality.

The ruling class uses its power to establish the order of society.

“The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas: i.e., the class which is the ruling material force of society, is at the same time its ruling intellectual force. The class which has the means of material production at its disposal, has control at the same time over the means of mental production, so that thereby, generally speaking, the ideas of those who lack the means of mental production are subject to it.”[5]

In other words, the ruling class has the time and money to produce ideology.

American society is rife with examples of wealthy people using their wealth to advance ideology. Charles Koch and his late brother David Koch spent over $128 million funding the Mercatus Center, a think-tank at George Mason University. The Mercatus Center is an economic think-tank that emphasizes free market liberalism. With its proximity to Washington, D.C., the Mercatus Center presents its “experts” to government and news media to demonstrate the benefits of the free market in seemingly un-ideological terms. But these goals unequivocally advance the Koch brothers’ financial goals. More recently, Jeff Bezos’ purchase of The Washington Post has allowed him to advance both his direct financial interests[6] and his ideological interests as demonstrated by his recent changes to the editorial content.[7] And Elon Musk’s purchase of Twitter allows him to promote and suppress content based on his own opinions.[8]

Since ideology operates in the background, by-and-large people are not aware of its functioning. Italian social theorist Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937) discussed the way ideology operates to create an all-pervasive power, hegemony. For Gramsci, “particular social groups struggle in many different ways, including ideologically, to win the contest of other groups and achieve a kind of ascendancy in both thought and practice over them.”[9] This is hegemony—the power of one class to rule over another class. Gramsci was not only talking about economic and political power, but also cultural power. Cultural has the ideological power to help aid social control. Cultural hegemony. Cultural Hegemony is the idea that we consent to the ruling class; we accept the ruling class’s ideology because we get something in return. Hegemony seems natural or “common sense,” but Gramsci argues we must have “good sense”—i.e., critical thinking skills that require thinking against power.

Frankfurt School

When people refer to critical theory, they usually mean the Frankfurt School. Associated initially with The Institute for Social Research at the University of Frankfurt, the Frankfurt School was a group of German-Jewish intellectuals conducting social science. People associated with the Frankfurt School include Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Herbert Marcuse, Walter Benjamin, Leo Löwenthal, Erich Fromm, and Friedrich Pollock. Their interest was with how power operates through domination. For the Frankfurt School, much like Gramsci, domination wasn’t just the police or military power of the state, but also the way it is exercised through culture.Frankfurt School

With the rise of the Nazi party, many of the members of the Frankfurt School escaped and made their way to America. After escaping fascism in Europe, they looked at the United States and determined it too was fascist, but in a different way. First, there were the obvious racial and ethnic elements of fascism from Jim Crow segregation to the Japanese internment camps. But they also explored the way the United States treated consumption like a religion. In fact, Herbert Marcuse argued that this obsession with consumption made people “one-dimensional.”[10]

One aspect of social life they explored was the expansion of consumption in the 20th century. To drive consumption to higher levels, capitalists realized they needed to create more consumer goods for people with disposable income. To do so, capitalists recognized the “growing importance of leisure and consumption activities.”[11] Culture, and consumption itself, became a significant part of people’s lives. Marcuse[12] and Walter Benjamin[13] showed the act of shopping itself became a leisure activity. To drive consumption, capitalists have to produce more and more goods. The problem is that this expansion of consumption leads to domination and mass manipulation.

The Frankfurt School argued that sustained critical thought was the only way to avoid domination. Readers often perceived their work as very pessimistic and bleak. Yet, it is important to remember that they experienced the Holocaust and the horrors of nuclear weapons. There was not much to be happy about in their time. And they feared that human beings would continue to deploy domination on each other. Sadly, in the 21st century, we continue to make the same mistakes and avoid thinking about the consequences of our actions.

Culture Industry

The most famous text by anyone associated with the Frankfurt School is “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception,” a chapter from Dialectic of Enlightenment published in 1944. The Enlightenment was a period of time (around the 18th century) in Europe where science, rationality, and freedom would prevail over myth and religious dogma. However, without critical thinking, the Enlightenment project became a new source of myth and dogma. Writing in the wake of World War II, Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer witnessed the horrors of the Holocaust, nuclear war (Hiroshima and Nagasaki), trench warfare, blitzkrieg, and Japanese internment. Adorno and Horkheimer asked: where is the progress promised by the Enlightenment? How do power and domination operate in enlightened times?

To answer these questions, Adorno and Horkheimer viewed mass culture as a major contributing factor to transmitting a new age of myth. As a result, they developed a perspective they called the “culture industry” to describe this era of “mass deception.” By linking culture with industry, the term culture industry does two things. On the one hand, it highlights culture as “possessing connotations of refinement, learning, and aesthetic contemplation.”[14]On the other hand, industry links it directly with capitalism. For Adorno and Horkheimer, culture should have nothing to do with capitalism, but culture produced by the culture industry follows the commodity logics of all other commodities.

Adorno and Horkheimer link culture with industry to identify the top-down production of culture industry commodities. At the time, the preferred word was “mass culture,” but Adorno and Horkheimer thought this term has a connotation of culture emanating from the masses. Culture industry reverses that relationship to demonstrate that these commodities emerge from the corporate board room instead of the street. They also distinguish culture industry from popular culture because popular or folk culture implies that it was created by the people. Rather, culture industry produces homogenized culture that articulates power.

Leisure time for most people is an early 20th century invention. In our time off from work, we want to relax and be entertained. The culture industry produces commodities that are supposed to make us feel good. But Adorno and Horkheimer argue “amusement under late capitalism is the prolongation of work.”[15] People work more to have time off and they look forward to their leisure time. Workers may spend their money on a movie on the weekend or save up to go on a cruise during their vacation. While leisure time may be necessary to relieve workers from the grind of their daily job, they also think about work while at leisure. More importantly for Adorno and Horkheimer, one person’s leisure time is another person’s working time. In other words, leisure for one person is exploitation for another person. To see a movie, hundreds of people produce the film, distribute it to theaters, and take tickets, sell popcorn, clean, and otherwise run the movie theater. The example of the cruise ship is even more exploitative as the cleaning staff lives on the ship for very low wages in segregated spaces.

The products of the culture industry work with the logic of capitalism. They sell the ideology of those people in power. Workers feel like they enjoy movies, television, video games, music, vacations, etc., but Adorno and Horkheimer see these as just levers of power to distract the masses. Many scholars have criticized Adorno and Horkheimer for their bleak vision because enjoyment is an important part of life. Whether or not we get enjoyment out of the products of the culture industry, it is also important to always remember the products are commodities that generate profits and produce ideology. I’ll remember this as I watch the next Marvel movie!

Media Concentration and Conglomeration

Before we can think about the role of labor in culture industry, its important acknowledge the role of media concentration.[16] Large corporate conglomerates create most of the popular culture available for consumption. A nearly infinite supply of television shows, movies, video games, books, music, television shows, and comics seems to exist, but only a small number of corporations produce them, and this gets worse every year as companies merge.

At the time of writing, there were three major record labels, six film studios, and five book publishers. Some of the largest conglomerates are Sony, Time Warner, Walt Disney, Viacom, CBS, Comcast, and 21st Century Fox, but they are always further conglomerating. In the early days of television, there were three TV networks—CBS, ABC, and NBC. Who owns the big TV networks? Disney purchased ABC, which also owns ESPN along with the streaming service, Hulu. CBS is owned by Paramount, which also owns Viacom which includes MTV, BET, Nickelodeon, Country Music Television, among others. NBC’s parent company is NBCUniversal, which includes numerous television and film studios and production companies. Ultimately, cable company Comcast owns NBCUniversal. The overlap between entertainment entities feeds homogenization in content.

Radio feels like it is decentralized, but because of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 the radio industry is hyper-conglomerated. The Telecommunications Act eliminated caps on how many broadcasters one company can own. The largest owner of radio stations in the United States is iHeartMedia, which used to be iHeartRadio before it combined with online media content. Even earlier it was called Clear Channel and reached into live events via Live Nation. iHeartMedia owns 858 broadcast radio stations in the United States of America. The next largest is Cumulus Media which owns 454 radio stations.

While there might be 858 different radio stations, they all have the same content. In every market in the United States, iHeartMedia, owns several stations. iHeartMedia owns different stations in different markets, and every station’s content is produced at the same location. For each station, iHeartMedia will have an artist say, “Hey, Dallas. Thanks for listening to KXYZ. Enjoy that hot weather!” The artist sits in a booth, and they do a dozen of these statements, and it gets played in a dozen different markets. This makes the station feel like it is local, but it’s not because the programming is happening at the corporate headquarters, and so this is happening on all these different media platforms, and it’s a result of the Telecommunications Act of 1996 which, quote unquote, deregulated media ownership.

For local television broadcasting (ABC, CBS, and NBC affiliates) Sinclair Broadcaster owns the largest number of local stations. It is a conservative media organization that explicitly tries to engage in politics on its stations. They own 172 local TV stations, and what they were doing on Sinclair Broadcast groups – they were having similar stories produced in different markets that were coming from the corporate center. And these, again, have a political partisan orientation to them.

Finally, most Americans receive their news from a handful of newspapers and online news organization. The largest newspaper conglomerate in the US is the Gannett Company which owns 80 newspapers, including the largest newspaper in the United States, USA TODAY.

Media ownership impacts the kind of content available to people. The information we receive is tightly controlled by a small group of wealthy people. According to the critical approach, they use these outlets to produce and reinforce ideology. At the same time, they reduce labor costs to increase profits.

Labor Theory of Value

Classical economics from Adam Smith[17] to Karl Marx[18] used the labor theory of value, the simple idea that labor creates all value. Labor is a commodity that works like all other commodities. Supply and demand impact prices of commodities. When supply is up and demand is low, prices go down; when supply is low, and demand is high, prices go up. The price of a labor’s commodity is its wage. According to the labor theory of value, capitalists generate profit by underpaying workers for their labor.

Workers produce goods for capitalists. They do so to earn a wage to pay for their needs. They must work for capitalists because they do not own the means of production. Capitalists give workers access to the means of production to produce commodities. The trick to capitalism is that workers never receive pay for the value they create; they always earn less. Whether that involves workers earning minimum wage to clean movie theaters or movie stars earning $10 million for a role, the people, or companies they work for pocket the extra value they create with their labor.

In the culture industry, corporations obscure labor to the point where creative workers don’t see themselves as workers and consumers view those workers as overpaid for their talent. The resulting situation makes labor in the culture industry very precarious.

Artists as independent contractors

At the 2025 Grammys, Chappell Roan called out record labels in her Best New Artist winning acceptance speech.[19] She stated, “I told myself if I ever won a Grammy, and I got to stand up here in front of the most powerful people in music, I would demand that labels and the industry, profiting millions of dollars off of artists, would offer a livable wage and health care, especially to developing artists.”[20] To many non-artists in my research, this comes as a surprise.[21] People believe that if someone signs a record contract, they are instantly rich and famous. The truth is record labels never bring most albums to market and for those whose music becomes commercially available, most never earn a dime.

The problem is often, as Chappell says, “record labels need to treat their artists as valuable employees with a livable wage and health insurance and protection.”[22] Recording artists are not considered employees, but rather independent contractors. As independent contractors, record labels do not owe their artists the basic benefits for labor as required by law: no minimum wage, no health care, no 40-hour work week, no family and medical leave. Everyone else who works at the label, from the CEO to the janitorial staff, earns a wage and is protected by laws. Yet the people who record music, do not earn a wage or experience the benefits of employment.

A record contract works by giving an artist an advance on their royalties, then they must pay back the advance on their portion of the royalties. A royalty is the amount artists earn from the sale (or stream) of their music that is usually 10-15% of the sale. The advance is similar to a loan, but instead of having to pay back the loan or default, recording artists have the terms of the advance connected to future albums. With that advance, artists have to record and market their album. A typical artist makes $20,000 from a $500,000 advance as a stipend over two years. That means that each member of a 4-piece band earns $5,000 in two years from throyalty eir record contract.

It is easiest to discuss these terms in relation to CDs. If an artist earns a 10% royalty from the sale of the CD, they net $1 per CD. If they receive a $500,000 advance, they must pay back the advance with their $1from every CD sold. This means they would have to sell 500,000 CDs before they recouped the advance. At 500,001 CDs sold, they earn a dollar. Most artists never come close to this many albums sold as 500,000 is the number of albums sold for the Recording Industry Association of America to certify an album “gold.”

The situation is dire for artists. They have to work really hard to sell albums, or get digital streams, but the work they put into these efforts pays very little. At the same time, record labels also receive a 10% royalty from the sale of every album. In the above scenario, labels recoup at 250,000 albums sold. Between 250,000 and 500,000 albums, the label continues to earn their royalty and the artist’s royalty; therefore at 500,000 albums sold, record labels have already profited $500,000 before the artist earns a dollar.

Some recording artists like Taylor Swift, Metallica, Drake, Rhianna, or Ed Sheeren sell hundreds of millions of records. They have massive tours that gross billions of dollars. They have staggering net worths. The system works for them, and they are the most visible artists. But most artists never recoup their advances and live a life of poverty.

Internships

America runs on free labor for the dream of future work. While musicians signing record contracts is an obvious way they live this dream,[23] the American economy is filled with people hoping to get jobs one day who are willing to do the job for experience for low to no wages. Lauren Berlant calls the pursuit “cruel optimism”[24] because these people who dream a better life become mired in the reality of their dreams. I called this process the ideology of getting signed.[25] One of the places this is most disturbing is the demand for internships, and the culture industry is a regular exploiter of these dreams.

College students are told they need to get an internship in order to gain experience to acquire a job. Often, these internships are unpaid. When they do these jobs, they rarely gain experience doing the job. Instead, companies bring interns to make copies, answer phones, and make coffee. These are tasks that used to be paid tasks by administrative assistants, but companies utilize free labor.

Since interns are willing to do menial labor for companies, those companies don’t hire as many administrative assistants. As a result, these workers go into the reserve army of labor and must compete with other would-be workers for jobs and wages. Remember labor is a commodity, so it follows the commodity logics of supply and demand. More workers willing to do a job means higher supply, but for fewer jobs, which lowers wages.

Pseudo-individuality

Another strategy of the culture industry is to produce what worked before. The low-risk strategy offers consumers something similar to what already sells. For example, if a comic book movie does well at the box office, other movie studios mine comic book content to produce a similarly popular movie. Consumers feel like they get something different that represents them, but the differences are small. Adorno and Horkheimer call this pseudo-individuality – a deception whereby people feel like their consumption tastes represent their individual choices, but they really reflect limited options. No where is pseudo-individuality clearer than the music industry in the late 1990s.

In 1997, Jive Records signed Britney Spears. At the time, the 15-year-old blonde former Disney star had name recognition. She was an immediate success on the music charts with her debut album . . . Baby One More Time selling more than 14 million albums. Her success on the charts led other labels to take notice. And then after she turned 18, she did it again with Opps! . . . I Did It Again (2000).

Columbia Records then signed fellow blonde former Disney star, Jessica Simpson. However, the slight difference between Spears and Simpson was the latter’s marketing as a wholesome Christian girl. Because Simpson fit the formula, she was guaranteed success in the recording industry. And sure enough her first album Sweet Kisses (1999) charted at 25 on the Billboard 200 and sold 2 million albums.

Not to be outdone, RCA Records signed Christina Aguilera who is once again an attractive blonde singer. This time with a caveat: she wasn’t on Disney but had tried out unsuccessfully for the same iteration of the Mickey Mouse Club that starred Spears and Simpson. “When I came into this business, there was a really big pop boom, and it was very specific what a label wanted a pop star to look like, to sound like.”[26] This time the difference was Aguilera’s Latin influence. Her first album Christina Aguilera (1999) reached number 1 on the Billboard 200 with over 9 million albums sold to date.

The idea is not to take away credit from any of these singers’ musical talent, but rather to highlight how the industry tries to produce the same thing if it sells elsewhere. Record labels in the culture industry try to produce similar products to sell to the public. They know that if people buy Britney Spears’ music, they will buy something similar. They make each product similar with a slight difference to make people feel like they are consuming something different, often creating slightly different markets.

Pseudo-individuality makes it seem like we have options, but the culture industry produces uniformity. In turn, uniformity produces conformity as we submit to the logics of the culture industry.

Discrimination and Stereotypes

Hollywood and the culture industry are rife with discrimination and stereotypes, much like the rest of American society. But the culture industry possesses the power to perpetuate ideology. Popular culture produces the ideas we think by reflecting the worst of our collective sensibilities back at us. For instance, comedians earn money by making fun of people. Making fun of people usually starts with focusing on stereotypes. While Hollywood traffics in stereotypes, it discriminates and oppresses workers behind the scenes.

When people aspire to positions, it helps for them to see people like them at the top. However, few top managers in media companies are women—especially not women of color. Furthermore, sexual harassment stops women from being able to pursue positions as executives in the culture industry. Two movements that exposed the prevalence of sexual harassment and assault in the music industry—#MeToo (film) and #TimesUp (music) highlight the domination women face in the culture industry. Harassment creates more inequity by having few women at the top. #MeToo and #TimesUp are movements that demonstrate how pervasive misogyny is in the entertainment industry and America.

Hollywood perpetuates stereotypes. The term stereotype comes from the printing press—a relief printing plate cast in a mold made from composed type or an original plate. The term became more widely used as a widely held but fixed and oversimplified image or idea of a particular type of person or thing. In films and television, male villains are often ethnic caricatures, sometimes in Black/Red/Brown Face. Female villains are portrayed as unstable.

In turn stereotypes change the types of roles available to actors. Few Black actors have been nominated for Oscars. Those nominated tend to play roles of homeless, violent, or criminal characters. This led to #OscarsSoWhite, a social media tag started on Twitter to highlight the lack of representations of people of color in the Oscars.

As actors accept roles for certain types of characters, they become typecast. Aziz Ansari used his TV show, Master of None, to show how typecasting creates roles for actors. In “Indians on TV,” Ansari shows how casting directors always look for Indian-American actors to use an Indian accent to play roles like taxi driver or store clerk—roles that do not require an accent to be delivered effectively.[27] However, he is always asked to “do the accent.” At the same time, Ansari shows that only white straight men get to be the “everyman.”

The most disturbing part of Ansari’s “Indians on TV” episode[28] is the logic played by fictional executive Jerry Danvers. When pressed by Ansari’s character, Dev, why there can’t be two Indians on a TV show, Danvers says there can be one but there can’t be two. Danvers says he doesn’t care, but the American public isn’t ready for a show with 2 Indians. No poll is given, the people don’t vote, the assumption comes from Danvers’ gut. And Danvers’ cut is filled with stereotypes. This creates the homogenization of the culture industry without any input from the audience.

Democratic Consumption

I started this chapter discussing voting in the culture industry. Unfortunately, everything in the culture industry depends on the sale of commodities as a vote. We vote with our wallets.

Adorno and Horkheimer describe this as “democratic consumption.” The culture industry tells us it gives us what we want because the content sells the most. Supposedly we can tell the best in culture by what people buy (Billboard Charts, Ticket sales, Nielsen ratings). Consumers vote with their money.

What about people who don’t have money to consume? Do they get a vote? The answer is their vote only counts to the degree they can purchase the culture industry’s commodities. For this reason, “good” can’t be equated with “popular.”

More importantly, the choices are limited. If you want something that isn’t produced or marketed, there is no way to “vote” for it. And this is a big reason marketing is so important to popular culture. People buy what they are told they want to buy.

While the culture industry tells us that measurement is key to understanding the masses, measurement itself is a key product of the culture industry. “The masses are not the measure but the ideology of the culture industry, even though the culture industry itself could scarcely exist without adapting to the masses.”[29] By claiming the culture industry produces content for “us,” it places itself as a neutral observer, but it produces the culture we consume.

This is why the concept of democracy is so important. Democracy requires people to participate, not choose between two products. For the people to rule, they have to understand the terms of debate. Meanwhile, the culture industry obscures its process by telling the people it serves them. It does not.

To look at popular culture through critical theory means to analyze the interests behind the content we consume.

Bibliography

Adorno, Theodor W. “Culture Industry Reconsidered.” New German Critique, no. 6 (1975): 12–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/487650.

Arditi, David. Digital Feudalism: Creators, Credit, Consumption, and Capitalism. SocietyNow. Emerald Publishing, 2023.

Arditi, David. “Digital Subscriptions: The Unending Consumption of Music in the Digital Era.” Popular Music and Society 41, no. 3 (2018): 302–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2016.1264101.

Arditi, David. Getting Signed: Record Contracts, Musicians, and Power in Society. Palgrave Macmillan, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44587-4.

Arditi, David. iTake-Over: The Recording Industry in the Streaming Era. 2nd edition. Lexington Books, 2020.

Arditi, David. Streaming Culture: Subscription Platforms and the Unending Consumption of Culture. SocietyNow. Emerald Publishing Limited, 2021.

Bailey, Alyssa, and Lauren Puckett-Pope. “Chappell Roan Calls Out Record Labels in Her Impassioned 2025 Grammys Acceptance Speech.” Celebrity News. ELLE, February 3, 2025. https://www.elle.com/culture/celebrities/a63642360/chappell-roan-speech-grammys-2025-transcript/.

Baker, C. Edwin. Media Concentration and Democracy: Why Ownership Matters. Communication, Society, and Politics. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Benjamin, Walter. The Arcades Project. Third Printing edition. Translated by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin. Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press, 2002.

Berlant, Lauren. Cruel Optimism. Duke University Press Books, 2011.

Bond, Shannon. “2 Years in, Trump Surrogate Elon Musk Has Remade X as a Conservative Megaphone.” Elections. NPR, October 25, 2024. https://www.npr.org/2024/10/22/nx-s1-5156184/elon-musk-trump-election-x-twitter.

Burns, Jehnie I. Mixtape Nostalgia: Culture, Memory, and Representation. Lexington Books, 2021.

Drew, Rob. Unspooled: How the Cassette Made Music Shareable. Duke University Press Books, 2024.

Gay, Paul du, Stuart Hall, Linda Janes, Hugh McKay, and Keith Negus. Doing Cultural Studies: The Story of the Sony Walkman. 2nd ed. SAGE, 2013.

Hall, Stuart, Jessica Evans, and Sean Nixon, eds. Representation. 2nd ed. Sage: The Open University, 2013.

Harrison, Anthony Kwame. “’Cheaper than a CD, plus We Really Mean It’: Bay Area Underground Hip Hop Tapes as Subcultural Artifacts.” Popular Music 25, no. 2 (2006): p.283-301.

Horkheimer, Max, and Theodor W. Adorno. “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception.” In Dialectic of Enlightenment. Herder and Herder, 1972.

Kellman, Laurie. “Washington Post Owner Jeff Bezos Says Opinion Pages Will Defend Free Market and ‘Personal Liberties.’” Politics. AP News, February 26, 2025. https://apnews.com/article/washington-post-bezos-opinion-trump-market-liberty-97a7d8113d670ec6e643525fdf9f06de.

Marcuse, Herbert. One-Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society. Beacon Press, 1991.

Marx, Karl. Capital: Volume 1: A Critique of Political Economy. Penguin Classics, 1992.

Marx, Karl, and Friedrich Engels. “The German Ideology.” In The Marx-Engels Reader, 2nd ed., edited by Robert C. Tucker. Norton, 1978.

Mier, Tomás. “Christina Aguilera Meets Raye: Two Vocal Powerhouses Dream of Duets.” Rolling Stone, October 21, 2024. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/christina-aguilera-raye-singing-duets-1235133001/.

Smith, Adam. The Wealth of Nations. Edited by Edwin Cannan. Bantam classic. Bantam Classic, 2003.

Smith, Paul, Alexander Monea, and Maillim Santiago, eds. Amazon: At the Intersection of Culture and Capital. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2022.

Wareheim, Eric, dir. Indians on TV. Comedy. With Aziz Ansari, Kelvin Yu, Lena Waithe, and Ravi Patel. 3 Arts Entertainment, Alan Yang Pictures, Fremulon, 2015.

- Arditi, Getting Signed. ↵

- du Gay et al., Doing Cultural Studies, 80. ↵

- Arditi, iTake-Over; Arditi, Streaming Culture; Arditi, “Digital Subscriptions.” ↵

- Harrison, “'Cheaper than a CD, plus We Really Mean It’: Bay Area Underground Hip Hop Tapes as Subcultural Artifacts”; Burns, Mixtape Nostalgia; Drew, Unspooled. ↵

- Marx and Engels, “The German Ideology,” 172. ↵

- Arditi, Digital Feudalism; Smith et al., Amazon. ↵

- Kellman, “Washington Post Owner Jeff Bezos Says Opinion Pages Will Defend Free Market and ‘Personal Liberties.’” ↵

- Bond, “2 Years in, Trump Surrogate Elon Musk Has Remade X as a Conservative Megaphone.” ↵

- Hall et al., Representation, 33. ↵

- Marcuse, One-Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society. ↵

- du Gay et al., Doing Cultural Studies, 82. ↵

- Marcuse, One-Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society. ↵

- Benjamin, The Arcades Project. ↵

- du Gay et al., Doing Cultural Studies, 82. ↵

- Horkheimer and Adorno, “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception,” 10. ↵

- Baker, Media Concentration and Democracy: Why Ownership Matters. ↵

- Smith, The Wealth of Nations, Bantam classic. ↵

- Marx, Capital. ↵

- Bailey and Puckett-Pope, “Chappell Roan Calls Out Record Labels in Her Impassioned 2025 Grammys Acceptance Speech.” ↵

- Bailey and Puckett-Pope, “Chappell Roan Calls Out Record Labels in Her Impassioned 2025 Grammys Acceptance Speech.” ↵

- Arditi, Getting Signed. ↵

- Bailey and Puckett-Pope, “Chappell Roan Calls Out Record Labels in Her Impassioned 2025 Grammys Acceptance Speech.” ↵

- Arditi, Getting Signed. ↵

- Berlant, Cruel Optimism. ↵

- Arditi, Getting Signed. ↵

- Mier, “Christina Aguilera Meets Raye.” ↵

- Indians on TV. ↵

- Indians on TV. ↵

- Adorno, “Culture Industry Reconsidered.” ↵

Democracy means “rule by the people.” However, how the people rule remains a matter of contestation. In the United States, the emphasis is on voting. But the ancient Greeks saw democracy emerging from instilling the people with power through consensus.In Greek democracy, the expectation was that the people could only rule by being educated and communicating freely about the topics of the day. Communication requires a public sphere in which people discuss issues impacting governance. Voting was not necessarily part of democracy as the Greeks emphasized building consensus and they did not elect people to represent them.American democracy requires voting and little else from the citizenry to govern. But voting, the American expression of giving voice, permeates most elements of American life.

The term culture industry highlights the industrial logics behind mass produced popular culture. It demonstrates the bottom line for popular culture corporations is profit.

A dialectic shows that concepts are constituted by their negation (opposite). While the dialectic has existed since at least Plato in Ancient Greece, Marx uses the tool as outlined by German Philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Every order (thesis) contains its negation (antithesis), these contradictions resolve themselves in a new order (synthesis). It is Marx’s use of dialectic thinking that gave rise to critical theory because the method shows the constitution of power in society.

Capitalism is a social order characterized by the endless accumulation of capital.

Capital is a social relationship that congeals value created by workers in commodities.

The means of production are the materials, machinery, and money used to produce commodities.

Ideology is an upside-down vision of reality constructed by the dominant class in society to obscure the social conditions in which everyone lives.

Hegemony is an all-encompassing power that operates through force or consent. Cultural hegemony is a power we consent to as described by Antonio Gramsci.

Associated initially with The Institute for Social Research at the University of Frankfurt, the Frankfurt School was a group of German-Jewish intellectuals conducting social science. People associated with the Frankfurt School include Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Herbert Marcuse, Walter Benjamin, Leo Löwenthal, Erich Fromm, and Friedrich Pollock. Their interest was with how power operates through domination.

The Enlightenment was a period of time (around the 18th century) in Europe where science, rationality, and freedom would prevail over myth and religious dogma.

The labor theory of value is the simple idea that labor creates all value.

A royalty is a percentage or set amount given to the creator of a piece of culture.

The term stereotype comes from the printing press—a relief printing plate cast in a mold made from composed type or an original plate. The term became more widely used as a widely held but fixed and oversimplified image or idea of a particular type of person or thing.

Democratic consumption is the idea the most popular or best things are those commodities that sell the most. It substitutes personal taste with exchange value.