2 The Slap: Functionalism and Popular Culture

When one celebrity slaps another, everyone has an opinion about it.

In 2014, Solange Knowles repeatedly slapped her brother-in-law, Jay-Z, in an elevator with Beyoncé watching after the Met Gala.[1] Popular culture sleuths went to work and the consensus became that Jay-Z cheated on his wife. This narrative kept growing after Beyoncé released her wildly popular visual album Lemonade. On “Sorry,” Beyoncé sings a diss to “Becky with the good hair.” This line brought the elevator conflict back as Beyoncé fans thought “Becky” must be the woman with whom Jay-Z cheated on Beyoncé. Everyone had an opinion.

Chris Rock told a joke about Jada Pinkett-Smith at the 2022 Oscars ceremony. Will Smith stood up, walked to the stage, and slapped Rock while saying “keep my wife’s name out your mouth.”[2] It was a difficult moment to miss in the pop culture world. Everyone had an opinion.

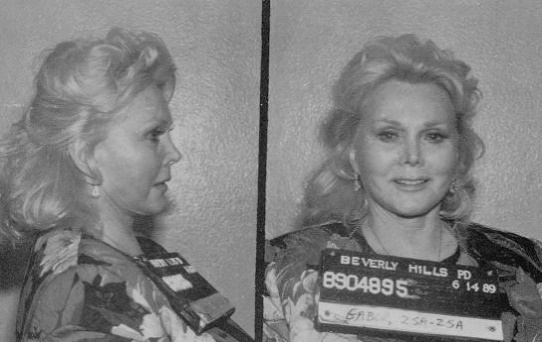

The first big celebrity slap came in 1989 when actress Zsa Zsa Gabor slapped a police officer in a traffic stop.[3] After being pulled over, Gabor took off in her $215,000 Rolls Royce. The officer pulled her over again and attempted to remove Gabor from the car when Gabor slapped him because she thought he was being rough with her. Everyone had an opinion.

But where these incidents may be personal, traumatic events for the people involved, their celebrity elevated the slaps to international points of conversation. What did Jay-Z do to Beyoncé? When is it okay to slap someone over a joke? Who has a right to discuss a slap? And if we look at it comparatively: how different would Gabor’s slap look if Will Smith slapped an officer? Race, class, and gender are always elements of what a slap means and how it is interpreted.

Wildfires ripped through Los Angeles, in January 2025, killing people, destroying property, and threatening the futures of people. On the other side of the country, the Los Angeles Rams played the Philadelphia Eagles in an NFL playoff game. Before the game, they had a moment of silence for the victims of the fires. Throughout the game the commentators instructed viewers to support their fellow Americans by donating to the Red Cross. The key is that even though two teams oppose each other on the field, they are all Americans.[4]

From a functionalist perspective, popular culture serves a function in society. First, popular culture helps to build solidarity among a large diverse population. This is why at sporting events between domestic opponents, someone plays the national anthem because it instills unity where games/matches place two cities against each other. Second, popular culture allows us to discuss difficult subjects without talking about people we know. We may discuss Solange, Smith, or Gabor without having to weigh-in on the personal affairs of friends, family, or colleagues.

Structural Functionalism

Popular culture serves a function in society. French sociologist Émile Durkheim (1858-1917) wanted to understand the role culture, and other institutions, play in society. Durkheim is known as one of the founders of sociology and developed the concept of structural functionalism. Structural functionalism looks at the way social system is held together. It is an analysis of the structure of society.

In his book The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, Durkheim looked at societies where religion was the central organizing institution of their existence.[5] He noticed that all religions had a heavy reliance on signs, images, and symbols derived from the natural world. While the signs were of importance to the societies, they did not make sense to outsiders. But Durkheim observed that regardless of the religion or symbols they all serve a function in society.

Durkheim demonstrated all the religions he observed had characteristics in common: sacred/profane, collective conscience, and collective effervescence. Regardless of the religious beliefs of any society, they had these characteristics. In turn, the understanding each group had of its religion bound people together.[6] Some of the rules and norms of any given religion might not make sense to an outsider, but Durkheim thought the opaqueness of these religious rules were also important for demarcating insiders from outsiders and formed the glue of the social fabric. In contemporary society, popular culture serves a similar function.

First, a group of people develops a collective conscience, which is a set of beliefs, ideas, and morals that bring a group of people together. This is the biggest point for Durkheim regarding religion. People create religion to structure their society instead of a god or gods bringing people together with these ideas. In The Division of Labor in Society, Durkheim shows that religion develops in small societies because it helps them to unify when there is little division of labor and groups were homogeneous. By creating strong moral rules about right and wrong, religious belief holds people together.

We see this in popular culture when people identify with each other over shared consumption of the same movies, TV shows, music, video games, influencers, comic books, etc. For example, the rules surrounding concert etiquette and attire. People who go to a rock concert in a stadium know to wear jeans and band t-shirts and scream to show support, but when those same people go to a jazz club to see a jazz trio, they wear business casual and applaud politely following a solo or a song.

Second, collective effervescence is the sensation a group of people experience when they are in one place feeling the same moment. In these instances, the group becomes herd-like moving and experiencing everything together. The best example of this is the vibe you feel at a concert. I’ve been to concerts where the collective effervescence makes me think it was the greatest show ever. Then I hear the recording later and it sounds awful. Getting “caught in the moment” is a product of collective effervescence.

Finally, Sacred (religious) and profane (secular) often make little sense to outsiders. Why can only a holy person touch a sacred object during specific times of the year? The distinction between secular and profane helps to distinguish self/other because the out-group would not know the distinction between sacred/profane. To an outsider, a sacred cup is just a cup. If they touch it, they know nothing will happen to them. And frankly, people in the group likely know nothing will happen to those who touch the cup even if their beliefs state the person who touches it will be damned eternally. However, something much deeper happens if a member of the group touches the sacred cup, they signal to the group they are “not like us.”

The power of “Not Like Us” by Kendrick Lamar isn’t the reality of Lamar’s diss of Drake, but the idea that someone is fundamentally not like us—i.e., not an insider. We can take that hook and run with it in any direction. At a football game, we could hear the hook and think how the opposing team acts. At a political rally, we could hear it and think about how the other political party doesn’t have our views. The point isn’t that claiming someone is “not like us” divides, but rather that it unifies those inside the group apart from those outside the group.

Social Solidarity

I began my freshman year in college in 2001. A couple weeks into the semester, two 747s crashed into the World Trade Center. At the next Virginia Tech football game, there were unprecedent displays of patriotism before the game, capped off by a B-2 stealth bomber flyover. The idea was that even though Virginia Tech would play the University of Central Florida on the field, we were all one nation.

When people feel a sense of connectedness with each other, they experience social solidarity. A strong sense of social solidarity creates social cohesion as the bonds between people create unity. Several factors create social solidarity. Knowing people through face-to-face interactions creates strong social bonds. Interdependence, usually around the division of labor in society, shows people they have to work together to survive. Symbols, rituals, and practices bring people together through shared values. For Durkheim, complex societies with diverse populations require the same elements as more homogenous smaller societies to bind them, but they require each other more due to their increased interdependence.[7] Lacking common religions in complex societies, culture helps produce a sense of social solidarity.

Sport teams provide the same type of glue that brings people together in contemporary societies. However, rivalries between teams also rips them apart. Durkheim sees these as centripetal and centrifugal forces.[8] Lacking a common religious practice, sports teams create social solidarity among a group of people. They include totemic symbols that represent them, which are usually animal symbols. These symbols then become representative of the city or region of the team. Team regalia allows fans to identify with the team and each other (ex. Green Bay Packers cheeseheads).

Sports resemble religions by creating ceremonies. Games, matches, and tournaments happen at a designated time. Football happens on Sundays (NFL), Saturdays (college), and Fridays (high schools). The NCAA Basketball tournament takes place during March Madness. The Super Bowl gets its own special Sunday. These events happen at designated spaces: stadiums, ballparks, arenas, etc. Sports have collective gestures from stadium waves to creating animal horns with their hands. Teams have incantations such as fight songs.

In all of these cases, sports in major cities bring people together along otherwise divided communities along race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Sports teams allow people to feel like a part of something in an otherwise disconnected environment.

The playing of national anthems and displaying of national iconography plays a role in creating national culture and unity at sports events. While opposing fans from different cities come together to support their team and city, sports leagues make an effort to reunite them under a common banner. Hence the strong display of nationalism in moments of crisis such as the Virginia Tech game mentioned above.

But even when there were huge claims to be one nation following the September 11, 2001 attacks, there remained exclusion. Anti-Muslim hate crimes increased 1,617% between 2000 and 2001.[9] According to the FBI, numbers of hate crimes committed against Muslims have not fallen below the 2001 level since.[10] Talib Kweli engages the idea of what it means to be American in the early 2000s in the song “The Proud.”[11] See Box 1 for an extended reading of the song.

Box 1 – “The Proud” by Talib Kweli

In the first verse, Kweli addresses the problems with coding all terrorist attacks as a Muslim problem in the aftermath of the death sentence of Oklahoma City Bomber Timothy McVeigh.

Today, the papers say Timothy McVeigh’s in hell

So everything’s okay and all must be well

I remember in Oklahoma when they put out the blaze

And put Islamic terrorist bombing on the front page

It’s like saying only gays get AIDS, propaganda

Like saying the problem’s over when they locked that man up

Wrong, it’s just the beginning, the first inning

Battle for America’s soul, the devil’s winning

. . .

They don’t wanna raise the babies, so the election is fixed

That’s why we don’t be fucking with politics

They bet on that, parents fought and got wet for that

Hosed down, bit by dogs, and got Blacks into house arrest for that

It’s all good except for that, we still poor . . .

The issue Kweli raises is that the press has an inherent inclination to present stories by blaming marginalized groups whether that is the Oklahoma City bombing or blaming gays for AIDS.

In the second verse, Kweli addresses issues related to unequal treatment for Black people through the justice system. He lays out different issues from “Prop 21,” which increased the penalties for graffiti, to the instance of a NYC drunk cop killing a family in Brooklyn then being released with no bail. While he is concerned about the justice system, the point is how he struggles to explain it to his son:

I want him living right, living good, respect the rules

He’s five years old and he still thinking cops is cool

How do I break the news that when he gets some size

He’ll be perceived as a threat or see the fear in they eyes?

Kweli wants the listener to know the problem in this system is that institutionalized racism in America makes his son a perceived threat to officers because of his skin color.

In the third verse, Kweli turns his attention to the attacks on the World Trade Center. As a New Yorker, Kweli witnessed the horror of the attacks and its aftermath first-hand. He lays out the way rescue workers and everyday people became heroes following the attack, but its hard for him to witness it because these same people were reviled before the attack. The verse feels like reconciliation with the first two verses, but he ends by stating that the attacks showed the United States caused problems around the world for decades and now is the time to “fight for our truth and freedom.”

Imagined Community

Popular Culture allows people to see themselves as part of national cultures. Historian Benedict Anderson developed the concept “imagined community” to show the way disparate groups of people unite to see themselves as part of one community, people, or nation.[12] For Anderson, national community develops through the development of print capitalism. Print capitalism emerges through a market logic following the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in 1440. Anderson says we never really had any idea of national identity until we get the rise of the printing press.

After the invention of the printing press, news stories could be presented to people over large areas in a common language. The printing press led to writing printed in national languages. In medieval Europe, the primary written language before the printing press was Latin, and the Bible was the primary written text. Monks worked in Catholic monasteries hand-writing the Bible over and over again in Latin. Part of the Protestant Reformation advanced the ability for people to read the Bible in their native tongue in Europe. This was a world changing moment. A common printed language then gave rise to European monarchies—governments that control larger areas of territory. At the same time, most people in Europe were illiterate, but the printed word functioned as a source of power by spreading language over larger territories.

On Great Britain, there are three nations, Wales, Scotland, and England, which spoke Welsh, Scottish, and English, respectively. Even today, the language is dramatically different in these three nations. Print capitalism facilitated the spread of proper English as the English monarchy consolidated power over England and later became the British monarchy.

If we focus on smaller territories, there were little feudal serfdoms all over England. People who live in small areas in medieval England would have separate dialects, over a very short distance because communication and travel were limited. However, the nobility moved around quite a bit. Proper English in Great Britain became referred to as the King’s English—i.e., the nobility’s English. The aristocratic class traveled around England and Great Britain, and they spoke a similar dialect. Eventually the aristocratic class’s language became the proper one. With the invention of the printing press, what language do they print in? The King’s English, which becomes codified in the Oxford English Dictionary. People in disparate places then began to identify with other people who spoke the same language.

As the printing press grew in use, newspapers became widespread. But since only wealthy powerful people could read, newspapers geared stories toward powerful people’s interests. If a person reads something in York about what’s happening in London, then they find out, “Oh, this is the thing that’s important. This is the thing that I’m supposed to care about,” and overtime, it gives more power to those in power.

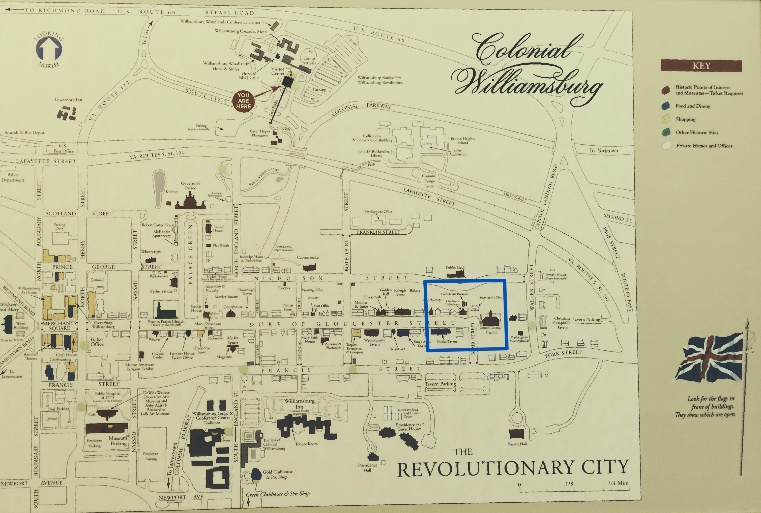

For Jürgen Habermas, this gave rise to what he termed the bourgeois public sphere.[13] Print newspapers enabled a bourgeoning class of capitalists to communicate what was important to them—mainly stock prices and events that impact stock prices. These publications enabled communication over distance and everyone else who could read was subjected to the reading interests of the bourgeoisie and the aristocracy. In Colonial Williamsburg, the colonial capital of Virginia, this is visible with the proximity between the stock market, the capitol, and a coffee shop, all on a partial cul-de-sac. Those with money in colonial Virginia accessed news about stock prices in the paper, discussed events that would impact prices in the coffee shop, and influenced the men who legislated in the capitol.

In effect, the royal family in the United Kingdom brought together England and later Great Britain by instituting their language and culture through an imagined community. That’s why people follow the tabloids of what’s going on with the royal family, but in the United States, Americans don’t have royalty. Instead, popular culture creates an imagined community in 21st century America. Americans follow the lives of the Kardashians, Knowles-Carters, or Taylor Swift to understand the right (and wrong) way to live and make sense of the world.

Work and Watercoolers

After a decade of certain politicians attacking single mothers, the creators of the sitcom Murphy Brown pushed back by having the eponymous lead character give birth to and keep a child as a single mother.[14] Then-Vice President Danforth Quayle inserted himself in the storyline. While speaking in California about 1992 LA riots, Quayle blamed Murphy Brown. Quayle stated the “riots were caused in part by a ‘poverty of values’ that included the acceptance of unwed motherhood, as celebrated in popular culture by the CBS comedy series Murphy Brown.”[15] In reality, the riots were caused by the acquittal of four police officers who were caught on film brutally beating a Black man, Rodney King.[16] Single-motherhood and Murphy Brown had nothing to do with the riot. This became a controversy in the 1992 presidential election as everyone in America had an opinion about it.[17]

In 1992, most people in America who watched television had a choice of three network TV shows to watch during each primetime slot (8-11pm ET). Murphy Brown was a hugely popular show, peaking as the third most popular TV show in Season 4 according to Nielsen ratings.[18] After Quayle’s speech and subsequent comments, people tuned in to see the season premier, and the episode “You Say Potatoe, I Say Potato” (Season 5, Episode 1, 9/21/92) became its most viewed episode with 70 million viewers.[19] People watched to see the controversy play out and hear the writers’ response to VP Quayle. After watching the episode, people went to work the next day to discuss what they viewed. The imagined community of popular culture made large populations of people in the United States aware of the political issue brought to the fore by Murphy Brown and Danforth Quayle. In these instances, popular culture transcends its medium to be a topic of discussion throughout society.

In contemporary American society, we experience the world through popular culture. When we go to work, we talk about the popular culture we consume with our colleagues. We often refer to this as watercooler talk to highlight the fact that people engage in small talk in breakrooms at work while they grab a water or coffee. Popular culture serves a function. When everyone is aware of something that happens on a TV show, a controversy between celebrities, or a powerful person and a fictional character, it gives us the opportunity to discuss moral dilemmas. And it allows us to discuss these moral dilemmas while not directly gossiping about people we know.

During the Murphy Brown/Danforth Quayle controversy, people could discuss the issue of single motherhood at work without weighing directly into the trials and tribulations of friends and family. As sociologist David Grazian highlights, popular culture acts as a type of myth akin to Aesop’s fables or The Iliad and The Odyssey. Myths help people to make sense of abstract ideas through fictional characters. They are “stories we tell ourselves about ourselves.”[20] Celebrities and popular culture provide us the opportunity to discuss hot topics without offending those close to us for their own decisions because we are discussing the fictional or real lives of other people.

Conclusion

While popular culture serves a function to create social solidarity, establish an imagined community, and allow people to discuss social issues, it serves another function: it allows power to function. According to Italian theorist Antonio Gramsci, power operates through the consent of the people.[21] While power might operate over us, we still get something from the system to maintain it. In the case of popular culture, we can consume popular culture and temporarily forget about our miserable condition. We consent to the system because things could always be worse.

Therefore, popular culture can act as a pressure relief valve. We can watch political satire from Saturday Night Live to The Daily Show, both of which use irony to cut through the political topics of the moment. But they never really change anything. The week I wrote this, Saturday Night Live celebrated its 50th anniversary show. Fifty years of political commentary and no political science researcher could find a single instance where the show impacted political outcomes. Why? The show functions as a relief valve for us to let off steam and prepare for another week of drudgery at our jobs.

Bibliography

Alfonesca, Kiara. “20 Years after 9/11, Islamophobia Continues to Haunt Muslims.” ABC News, September 11, 2021. https://abcnews.go.com/US/20-years-911-islamophobia-continues-haunt-muslims/story?id=79732049.

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities : Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Vol. Rev. and extended. London ; New York: Verso, 1991.

Aniftos, Rania. “Everything That Happened Between Will Smith & Chris Rock Since the 2022 Oscars Slap.” Billboard, March 7, 2023. https://www.billboard.com/lists/will-smith-chris-rock-oscars-slap-timeline/.

“Dan Quayle vs. Murphy Brown.” TIME Magazine 139, no. 22 (June 1, 1992): 20.

Durkheim, Emile. The Division of Labor in Society. Edited by Steven Lukes. New York: Free Press, 2014.

———. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. Edited by Mark S. Cladis. Translated by Carol Cosman. 1 edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Fortin, Jacey. “That Time ‘Murphy Brown’ and Dan Quayle Topped the Front Page.” The New York Times, January 26, 2018, sec. Arts. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/26/arts/television/murphy-brown-dan-quayle.html.

Grad, Shelby. “Zsa Zsa Gabor, the Beverly Hills Cop and ’the Slap Heard ‘Round the World.’” Los Angeles Times, December 19, 2016. https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-zsa-zsa-gabor-retrospective-20161219-story.html.

Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. Edited by Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell-Smith. London,: Lawrence & Wishart, 1971.

Grazian, David. Mix It Up: Popular Culture, Mass Media, and Society. 2nd ed. W. W. Norton, Incorporated, 2017.

Habermas, Jürgen. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Studies in Contemporary German Social Thought. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1989.

Kishi, Katayoun. “Assaults against Muslims in U.S. Surpass 2001 Level.” Pew Research Center, November 15, 2017. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2017/11/15/assaults-against-muslims-in-u-s-surpass-2001-level/.

Kweli, Talib. The Proud. Quality. Rawkus Records, 2002. https://genius.com/Talib-kweli-the-proud-lyrics.

Petit, Stephanie. “JAY-Z and Solange’s Infamous Elevator Fight: Everything That’s Been Said.” People.Com. Accessed February 3, 2025. https://people.com/music/jay-z-solange-elevator-fight-everything-theyve-said/.

Reinstein, Mara. “Murphy Brown at 35: By the Numbers.” Television Academy. Accessed February 19, 2025. https://www.televisionacademy.com/features/news/online-originals/murphy-brown-by-the-numbers.

Rosenthal, Andrew. “THE 1992 CAMPAIGN: Murphy Brown; Get Ready, America: Murphy Responds.” The New York Times, September 4, 1992, sec. U.S. https://www.nytimes.com/1992/09/04/us/the-1992-campaign-murphy-brown-get-ready-america-murphy-responds.html.

Serrano, Richard A. “All 4 Acquitted in King Beating : Verdict Stirs Outrage; Bradley Calls It Senseless : Trial: Ventura County Jury Rejects Charges of Excessive Force in Episode Captured on Videotape. A Mistrial Is Declared on One Count against Officer Powell.” Los Angeles Times, April 30, 1992, sec. California. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1992-04-30-mn-1942-story.html.

- Petit, “JAY-Z and Solange’s Infamous Elevator Fight.” ↵

- Aniftos, “Everything That Happened Between Will Smith & Chris Rock Since the 2022 Oscars Slap.” ↵

- Grad, “Zsa Zsa Gabor, the Beverly Hills Cop and ’the Slap Heard ‘Round the World.’” ↵

- Note here that the use of “Americans” is a rhetorical tool. They aren’t concerned about a person’s citizenship, but the identity of people watching American football. ↵

- Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. ↵

- Durkheim, The Division of Labor in Society. ↵

- Durkheim, The Division of Labor in Society. ↵

- Durkheim, The Division of Labor in Society. ↵

- Alfonesca, “20 Years after 9/11, Islamophobia Continues to Haunt Muslims.” ↵

- Kishi, “Assaults against Muslims in U.S. Surpass 2001 Level.” ↵

- Kweli, The Proud ↵

- Anderson, Imagined Communities : Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. ↵

- Habermas, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. ↵

- Fortin, “That Time ‘Murphy Brown’ and Dan Quayle Topped the Front Page.” ↵

- “Dan Quayle vs. Murphy Brown.” ↵

- Serrano, “All 4 Acquitted in King Beating.” ↵

- Rosenthal, “The 1992 Campaign.” ↵

- Reinstein, “Murphy Brown at 35." ↵

- Reinstein, “Murphy Brown at 35." ↵

- Grazian, Mix It Up, 34. ↵

- Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. ↵

A functionalist perspective on popular culture posits that popular culture serves a function for society by creating social cohesion.

Structural functionalism is a way of understanding society through the function that different institutions, organizations,symbols, and ideas serve in society.

a set of beliefs, ideas, and morals that bring a group of people together and give them a sense of belonging.

Collective effervescence is the sensation a group of people experience when they are in one place feeling the same moment.

Social solidarity is the social bond between people within a group. It is often characterized by both internal and external pressures.

The concept “imagined community” was developed by Benedict Anderson to show the way disparate groups of people unite to see themselves as part of one community, people, or nation. Anderson develops the concept using the printing press as the initial means to create a shared sense of nation.