3 Transportation Programming and Evaluation

CHAPTER OVERVIEW

This chapter discusses transportation programming and evaluation, essential for decision-making in transportation planning, and is divided into Parts A and B. Part A outlines the decision-making process and criteria for programming transportation and transit projects for construction or implementation. The current phase of each project is documented within a four-year time frame. In the US, projects using federal funds must comply with and be specified in a State or regional Transportation Improvement Program (STIP or TIP), while a local government typically identifies projects in their Capital Improvement Plan (CIP). This section primarily focuses on federal programming of regional surface transportation projects, providing an overview of the overarching and evolving criteria for prioritizing surface and transit projects outlined in the Federal Funding Acts.

Transportation programming is not conducted in isolation; it is a crucial part of the project development process, essential for implementing the transportation plans, discussed in Chapter Two, within budget and time constraints. Due to the significant investment and long-term economic, environmental, and social impacts of transportation facilities, project programming and evaluation at regional and local levels are embedded within a larger regulatory and budgetary framework. This framework aligns with federal and state requirements for a Transportation Performance Management (TPM) approach, incorporating feedback loops between evaluation and future planning and programming decisions.

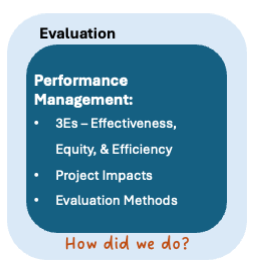

Part B explores transportation project evaluation, essential for assessing project performance and impacts. Evaluation is integral to the planning and programming process, as it helps determine the effectiveness and efficiency of projects. This section introduces six categorical impacts of transportation projects, whose evaluation may vary according to project characteristics. However, under a TPM approach, this process is vital for evaluating progress toward meeting planning goals and targets.

The three Es—equity, efficiency, and effectiveness—are briefly discussed. Efficiency, highlighted in the title of the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act (ISTEA), has long been a transportation goal. Effectiveness applies to various aspects of transportation planning, programming, service, and operations. Equity is introduced here as a precursor to Chapter Four, which focuses on transportation equity. Equitable transportation is emphasized throughout the book due to its significance in contemporary transportation planning and programming.

CHAPTER TOPICS

- Programming Elements

- Key Components of Transportation Programming

- Transportation Project Evaluation

- 3Es of Transportation Programming and Projects

- Conclusion

- Quiz

- Glossary

- Acronyms

Learning Objectives

- Identify common programming criteria in the decision-making process to prioritize transportation projects.

- Describe the steps in the programming and evaluation phase of the transportation development process.

- Explain the relationship of the three Es – Equity, Effectiveness, and Efficiency – to transportation programming and project evaluation.

- Discuss and give examples of the six categories of impacts to consider when evaluating transportation projects.

INTRODUCTION

Transportation programming is the process of prioritizing, selecting, and scheduling real-world projects from the transportation network envisioned in the agency’s long-term plan. As discussed in Chapter Two, planning and modeling articulate the envisioned future goals and objectives for transportation projects, typically delineated and mapped in the long-range Metropolitan Transportation Plan (MTP). A Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) is required to develop this plan to secure federal funding. Consequently, project programming is an outcome of the vision outlined in the MTP, which should also support the Federal Highway Administration’s (FHWA) national transportation goals.

For example, at the regional Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) level, the Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) is the list of priority projects ready for some level of implementation with estimated costs and identified funding sources. A programmed transportation project is generally generated from the Metropolitan Transportation Plan (MTP) and is usually a public project developed to provide a new facility or service and to enhance and maintain a current segment or facility of the transportation system. While the MTP has a horizon of 25 years, the TIP program has a 4-year horizon and is continually evaluated and updated as system needs are presented or changed.

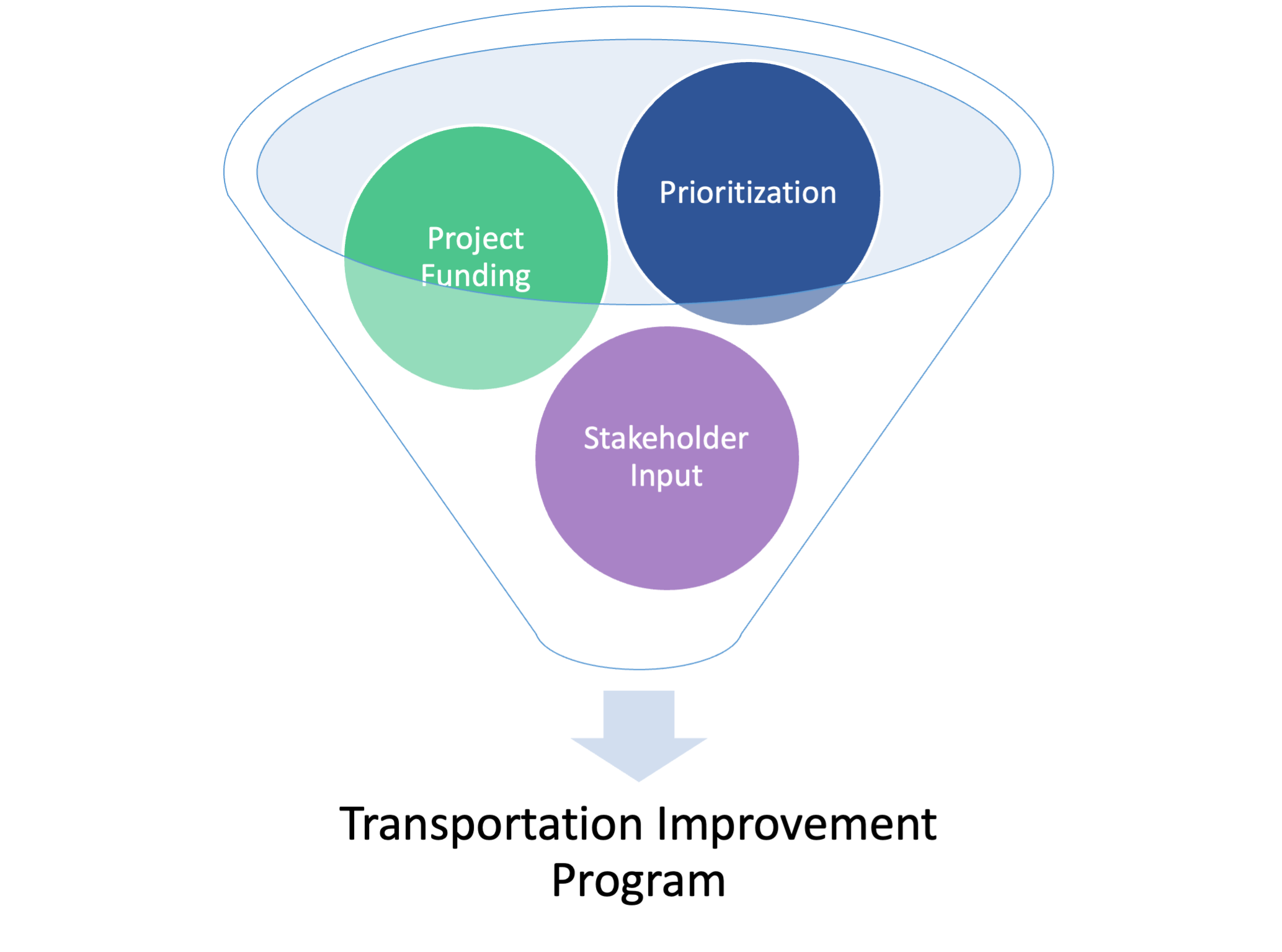

This chapter presents the next two steps of project development – programming and evaluation. Programming includes creating a viable financial plan for the funding of projects in a “program of projects,” also known as the TIP at the regional level. Project evaluation measures the impacts of facilities, programs, and projects to inform future transportation planning efforts and assess future improvements.

Role of Transportation Programming and Evaluation in Transportation Project Development

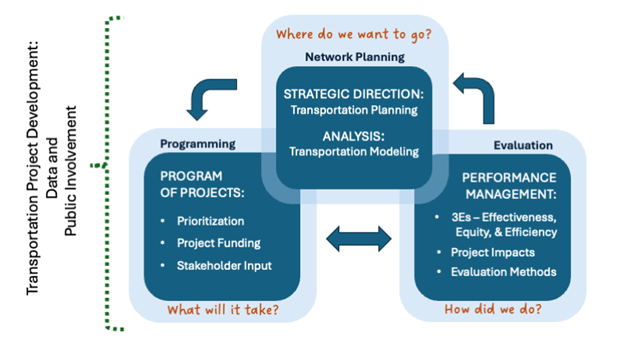

The programming and evaluation of a transportation project are two more steps in the development of transportation projects. It is important to emphasize that transportation planning, programming, and evaluation form a connected and iterative process that guides a transportation project or program from its initial concept and vision to the implementation of the actual transportation service or infrastructure. The planning phase, discussed in Chapter Two, sets the overall planning direction addressing the “Where do we want to go?“ strategic questions. It is itself an iterative process comprising numerous steps and feedback loops.

Figure 3.1 is the same figure presented and discussed in Chapter Two. It illustrates the connections between planning, programming, and evaluation, emphasizing the performance-based planning and programming (PBPP) approach. This chapter focuses on the two steps depicted by the lower two boxes – Programming and Evaluation. “PBPP is how State DOTs, MPOs, and transit providers implement Transportation Performance Management (TPM) within their transportation planning and programming processes to make investment and policy decisions to achieve national performance goals” (TPCB, n.d.). This approach is part of the Transportation Performance Management (TPM) framework elaborated by the FHWA in response to the 2012 Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act (MAP-21).

Watch the video “What is TPM and why does it matter “

Media 3.1 Federal Highway Administration USDOTFHWA. (2019, December 30). What is TPM and why does it matter? [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YyjW1Ua89Ug

Note: Notice that the TPM framework is a general planning, programming, and evaluation perspective and that the seven federal goals do not preclude MPOs and local public agencies (LPAs) from developing and including additional goals in their transportation plans.

Media 3.2 Federal Highway Administration USDOTFHWA. (2019, December 6). TPM Essentials: Performance Based Planning and Programming [Video]. https://youtu.be/nIyVE0MADZg

Note: This video provides a succinct explanation of the link between planning, programming, and evaluation discussed in Chapters Two and Three.

PROGRAMMING ELEMENTS

Project Identification

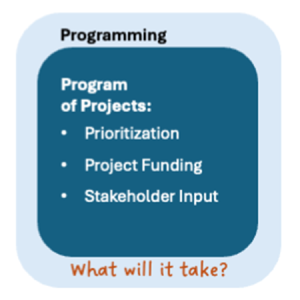

Part A of this chapter briefly presents transportation programming and includes three steps – prioritization, funding, and input – introduced below. When programming transportation projects (lower left block in Figure 3.1), the first step is to identify specific projects that address the specific transportation needs or system gaps and align with the established goals and objectives specified in the plan documents created during the planning phase (top block of Figure 3.1). Programming involves project prioritization, a very important process based on established agency criteria such as safety, congestion reduction, environmental impact, and alignment with community goals. It also guides the resource allocation intrinsic to project funding guided by the question, “What will it take?”

Box 3.1 Project Selection vs. Project Prioritization

It is important to differentiate between project selection and project prioritization. Prioritization is the cooperative process among states, MPOs, and transit agencies for identifying projects and strategies from the metropolitan transportation plan (MTP) that are of sufficiently high priority as to be included in the transportation improvement plan (TIP). Project selection, on the other hand, relates to identifying projects already listed in the TIP that are next in line for grant award and funding authorization.

Transportation Planning Capacity Building Program (TPCBP). (2018, webpage updated 2022). The transportation planning process: Briefing Book: Key issues for transportation decision-makers, officials, and staff (FHWA-HEP-23-001; DOT-VNTSC-FHWA-23-01). U.S. Department of Transportation,

Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/planning/publications/briefing_book/fhwahep18015.pdf

Project Funding

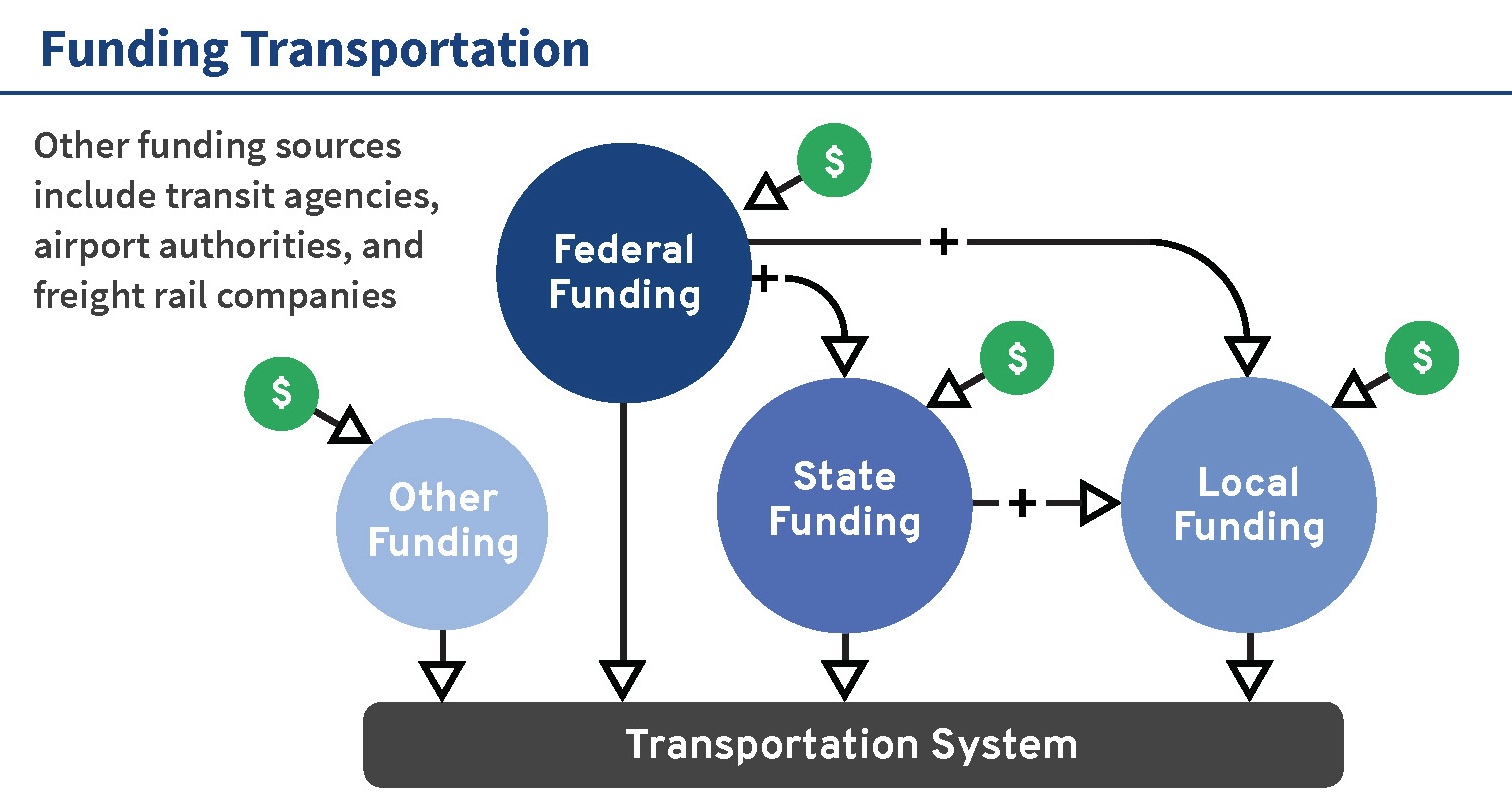

Financial planning begins in the transportation planning phase of project development. Without considering how projects may be funded, “the MTP could be viewed as nothing more than a ‘wishlist’ of good ideas” (FHWA & FTA, 2018, p. 3). Considering costs of transportation projects continues into the programming phase. Financial programming includes preparing for project implementation and construction by estimating costs and identifying funding sources that must be enumerated in the program document. Typically, funding comes from various sources, including federal, state, and local governments, private sector investments, grants, and other funding mechanisms. The result is a “program of projects” (NCTCOG 2025-28 TIP, 2024, p.I-1) detailed in the Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) document. Recall Figure 1.1, which depicts the typical flow of funds and monetary contributions to project development from federal, state, and local sources. The width and color of the arrows represent the transfer of funds or direct investment in support of the transportation project.

Stakeholder Input

All phases of project development require input from local officials, professionals, users, and residents. Recall Figure 1.1 During the programming phase, public participation assists and supports project selection and prioritization. Transportation demand management (TDM) was introduced in Chapter One which is focused on understanding how a traveler decides to get from the origin of the trip to the destination. Figure 2.6 in Chapter Two presents the typical inputs in the planning process. Traveler input in coordination with TDM informs project programming using stakeholder input discussed in a later section of this chapter.

Project Implementation

The next step is project implementation and evaluation, which are introduced here and discussed further in Part B of this chapter. This step involves developing technical documents – detailed project designs, construction documents, and specifications – and, again, incorporating public input. Community outreach and information programs are essential to secure federal funding and build community trust. Experts such as engineers, architects, urban planners, and other professionals coordinate and collaborate to design transportation infrastructure and systems that meet the project objectives.

Evaluation and Impact Assessment

Chapter Two introduced the role of evaluation in transportation project development. Performance goals outlined in long-range plans are aligned with specified performance measures and targets, which are then used to gauge the progress and performance of transportation projects. As discussed in the two videos in the previous section of this chapter, agencies involved in transportation project development are required to track, monitor, and report on project performance. These measures also facilitate transparent communication with the public, stakeholders, and funding sources. Tracking these measures ensures compliance and assesses the extent to which goals and objectives are met, addressing the question: “How did we do?” In turn, this information provides essential feedback applicable for future transportation project development.

While the effectiveness of implemented projects and programs is often evaluated in monetary terms, alternative evaluation methods are also used. This overview of planning, programming, and evaluation allows us to delve more deeply into programming in the next section, while continually keeping in mind the interrelatedness of planning, programming, and evaluation.

PART A: TRANSPORTATION PROGRAMMING- “What will it take?”

Introduction to Transportation Programming – “What will it take?”

Developing a transportation program, such as a Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) or a Capital Improvement Program (CIP), includes several steps that involve translating the facilities envisioned in the long-range plan into concrete projects. The fundamental purpose is two-fold: to advance the 3C process, including accountability to stakeholders, and to conform with federal law, including fiscal constraint. The North Central Texas Council of Governments (NCTCOG) 2023-2026 TIP explains, “Within metropolitan areas across the country, regional transportation projects are tracked through Transportation Improvement Programs. The Transportation Improvement Program, or TIP, is a staged, multi-year program of projects approved for funding by federal, state, and local sources within the Dallas-Fort Worth metropolitan area” (NCTCOG Transportation website, 2023). While projects are funded from a variety of sources, federal funding requirements tied to performance-based planning and programming set the overall scope and pace of transportation programming, as illustrated with the following examples.

Examples of Transportation Programming

The programming process at various agency levels typically uses tools like ranking, prioritization, and optimization to choose project types and locations that make the most of the available budget and schedule, maximizing system-level benefits. Below are examples of local-level Capital Improvement Plans (CIP) approaches from two U.S. municipalities: Bryan, Texas and Fairbanks, Alaska. At the regional level, transportation programming in the TIP process is presented by the Richmond Regional Planning Organization (RRTPO). At the state level, the Virginia Department of Transportation showcases the process in the state STIP.

Table 3.1 Programming examples.

(Click on the icon or the links to view the example of the programming document, noting the description of the methods used during the selection and prioritization process.)

| AGENCY | PROGRAMMING EXAMPLE |

|---|---|

| LOCAL | Bryan, Texas CIP |

|

|

|

| Figure 3.3 City of Byran CIP ranking system. From the City of Bryan, Texas (https://docs.bryantx.gov/CIP/future_CIP/cip_ranking_system_chart1.pdf). In the public domain. | |

| Fairbanks, Alaska CIP | |

|

|

|

| Figure 3.4 City of Fairbanks, North Star Borough CIP process. From City of Fairbanks, Alaska (https://www.fnsb.gov/DocumentCenter/View/7557/CIP-Process-PDF?bidId=) and (https://youtu.be/tOEQAND966o?feature=shared). In the public domain. | |

| REGIONAL | Southwest Washington Regional TIP |

|

|

|

| Figure 3.5 2023-2027 Southwest Washington Regional Transportation Council. From 2023-2027 Southwest Washington Regional TIP. (https://rtc.wa.gov/programs/tip/docs/ProgrammingGuidebook20230207.pdf) In the public domain. | |

| STATE | Virginai State DOT / STIP |

|

|

|

| Figure 3.6 Project selection process From Smart Scale, 2024. (https://smartscale.virginia.gov/how-it-works/). Copyright 2024 Smart Scale | |

| Note: Click in the upper right hand corner of each graphic to view the image in full screen. | |

For more information on project programming and Statewide Transportation Improvement Programs (STIPs) view the video below.

Media 3.3 Federal Highway Administration USDOTFHWA. (2016, August 26). Projects and Statewide Planning. [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qNsdyhTlPqE

The Transportation Improvement Program (TIP)

Historically, in the US, transportation programming is an outcome of federal law. The textbox activity below highlights the expanding prioritization criteria of each Act. Click on each Act to read about the priorities specified in the purpose statement. Since the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1962, programming has been based on the 3C (Continuing, Comprehensive, and Cooperative) approach, fiscal constraint, and performance management. Transportation programming aims to enhance mobility, multimodal facilities, operation improvements, accessibility, safety, efficiency, economic development, and sustainability in the movement of people and goods. Transportation programming is an ongoing, continuous process that requires collaboration, careful planning, and vigilant management to create a sustainable and efficient transportation system that meets the evolving needs of a community or region.

Evolution of Project Prioritization in Federal Acts

As previously noted, for the past several decades, transportation agencies have been transitioning toward performance-based approaches, specifically data-driven performance-based planning and programming (PBPP), to support decision-making (TPCBP, 2018, p. 2). Aligned with the Federal Acts’ national performance goals, PBPP allows state and regional transportation agencies to deploy a strategic and systematic process to organize and coordinate various transportation and transit improvement projects within a specific region or area. Additionally, the PBPP principles embedded in the FHWA TPM approach link “investment priorities to performance targets and make progress toward target achievement” (FHWA, 2020).

Key Activities of Transportation Programming

Key activities involved in the process of programming transportation projects at the state and MPO level, entail data collection, iterative analysis and evaluation, and public input until a final list of projects is determined and formally adopted by authoritative bodies like the Regional Transportation Council (RTC) of the Metropolitan Planning Organization and the State Transportation Board.

Figure 3.7 highlights three key activities that culminate in the listing of transportation and transit projects in the improvement program (TIP) – prioritization, financial planning, and public input – which “is the pinnacle of the transportation planning process and represents a consensus among state, regional, and local officials regarding selected projects for implementation.” (PlanRVA, 2022). This consensus is pivotal as it assures federal and state governments that all parties adhering to the 3Cs and establishing eligibility for federal funding have collaboratively developed priorities before committing funds to a project.

Prioritization

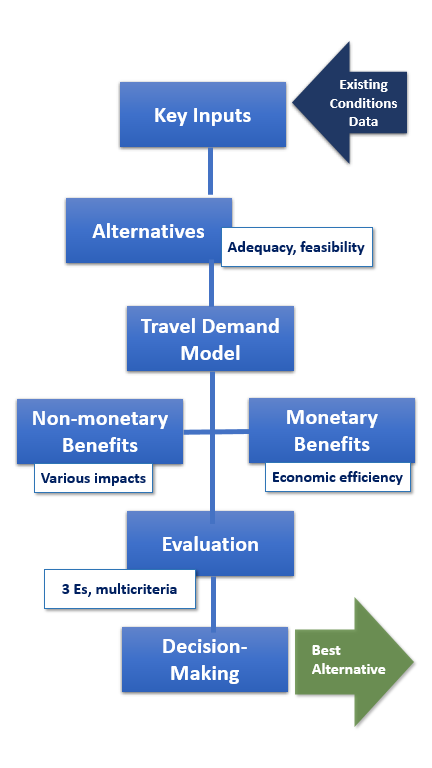

Project prioritization, the initial stage of programming, is critical as it deals with sensitive aspects of the process. State and regional transportation agencies must comply with federal laws and regulations related to various factors such as ecology, natural resources, air pollution, historic preservation, civil rights, and property acquisition. These requirements, including those aforementioned and established by the MAP-21 ACT under the transportation performance management (TPM) framework, are aligned with national goals and include performance targets and performance measures. These criteria guide the prioritization and selection of projects at the state and MPO levels, a process heavily reliant on data-driven project performance measures. Therefore, collecting and analyzing data objectively and comprehensively is essential in this process.

Figure 3.8 presents a flowchart from Sinha and Labi (2007), illustrating the complexity and multi-stepped project prioritization process. The decision to prioritize a project begins with gathering relevant data about existing conditions. These inputs are used to create and test several alternative scenarios for the form and function of the project until a selected project meets the agency-defined criteria and performance goals, such as travel time and safety, using statistical and mathematical models. For a more detailed discussion of land use and transportation modeling, refer to the OERtransport book, “Transportation Land Use Modelling and Policy .” Figure 3.8 also provides an overview of the major steps in the prioritization process, from data input to decision-making.

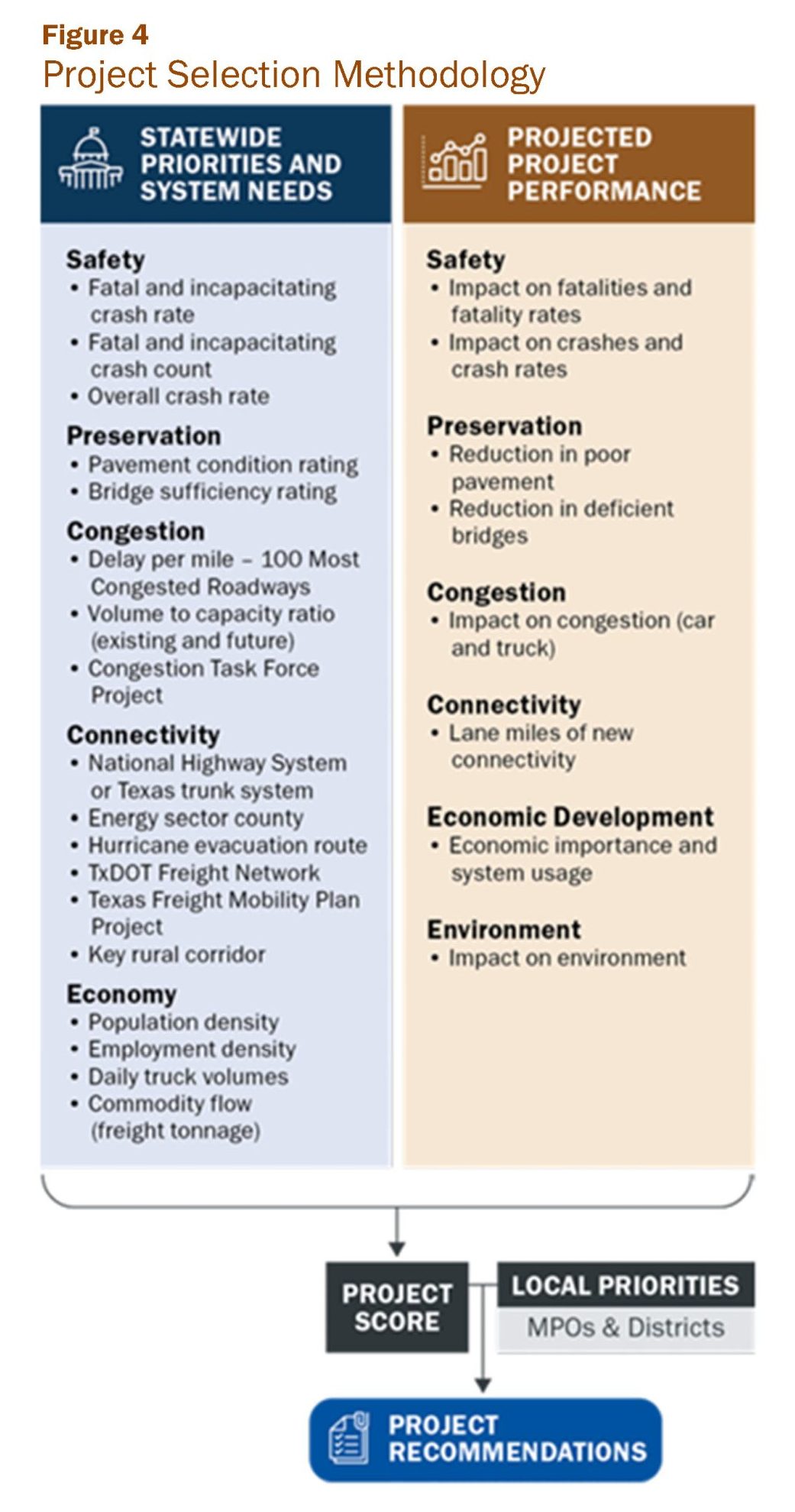

To further illustrate this prioritization process, Figure 3.9 is an example from the Texas Department of Transportation (TXDOT) showing the relationship between statewide system priorities and predicted project performance. The project under review is scored and ranked based on how it will meet local and regional performance goals and targets. At this point, the project may be included in the program of projects.

This example also underscores how state and regional transportation agencies develop specific procedures to identify and select transportation projects that align their long-range plan’s goals and performance measures with federal law. For instance, the 2012 Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century (MAP-21) Act first established federal requirements for performance measures and associated targets, which were continued under the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act. The main aim of these requirements is to ensure that states and MPOs invest their resources in projects that contribute to achieving the seven categorical national performance goals:

-

- Safety.

- Infrastructure condition.

- Congestion reduction.

- System reliability.

- Freight movement and economic vitality.

- Environmental sustainability; and

- Reduced project delivery delays. (FHWA, 2013, n.p.).

For more information on FHWA’s programming under TPM, consult the TPM Guidebook; specifically, the programming approach.

Project Funding

Development of each transportation project includes specifying funding from several sources. Like 1.1, Figure 3.10 depicts the major sources– federal, state, local, and other – which play a role in funding projects. It also reveals the relationship of funding sources to the transportation system. The Federal government both directly funds the transportation system as well as distributes funds to state and local governments through the Federal Aid Transportation Funding Acts presented in the previous chapters. State governments and Departments of Transportation also make direct investments into the system as well as financially coordinate and support local and regional agencies, such as the MPOs. Again, local fund sources are also used to develop transportation projects. Finally, beginning with the MAP-21 Act, the Federal government permits innovative finance and flexible funding, including fund transfers between FHWA and FTA. (USDOT, FHWA and FTA, TPCBP, 2018, n.p.)

Project Listings in the Transportation Improvement Program (TIP)

Since the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991 (ISTEA), funding responsibility has been integral to the planning and programming of public surface transportation projects as federal law requires fiscal constraint. Title 23, Section 450 of the Code of Federal Regulations requires only “projects for which construction or operating funds can reasonably be expected to be available may be included” in the improvement program ( 23 CFR 450.326.j, 2017).

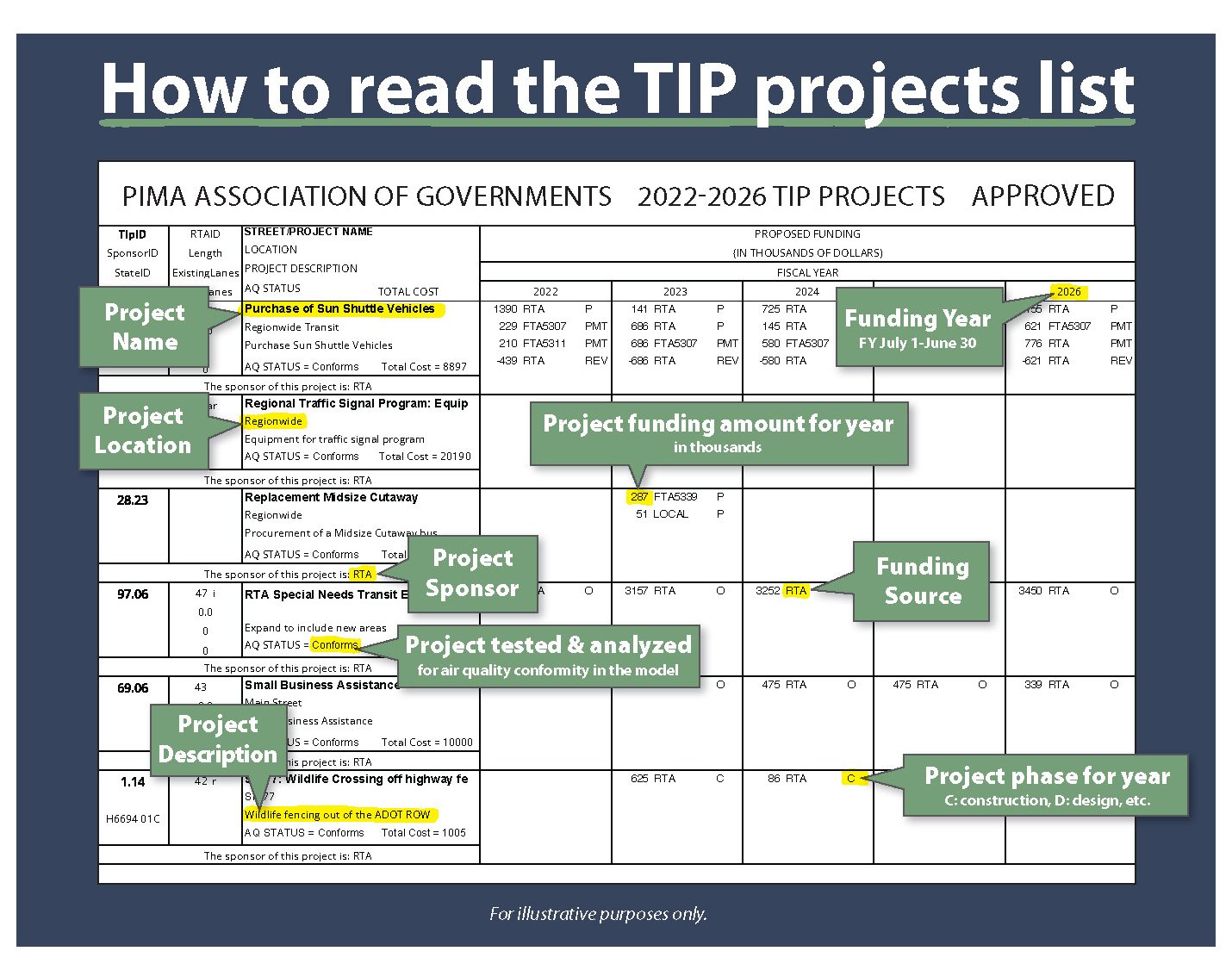

The transportation programming document, the STIP or the TIP, includes a listing for each transportation and transit project. To be included in the TIP, each project must first be a part of the adopted long-range transportation plan, the STP or the MTP. The TIP is a detailed document with technical information required by federal law. Figure 3.11 is an example from an Arizona MPO, the Pima Association of Governments (PAG). Title 23CFR 450.326(g) specifies what information must be included for each project in the improvement program document, including the project name, the funding year, the projected project cost, the project location and description, project phase, the applicable federal program, and funding sources (23CFR 450.326(g)). The figure below illustrates the different components of the TIP project sheet and demonstrates PAG MPO compliance with federal TIP requirements. Additionally, Title 23 CFR 450.326(i) stipulates that the TIP must be “consistent with the approved metropolitan transportation plan” (Title 23 CFR 450.326) discussed in Chapter Two.

Media 3.4 Federal Highway Administration USDOTFHWA. (2016, August 22). Funding Basics and Eligibility. [Video]. https://youtu.be/r0NBR4r3M7M

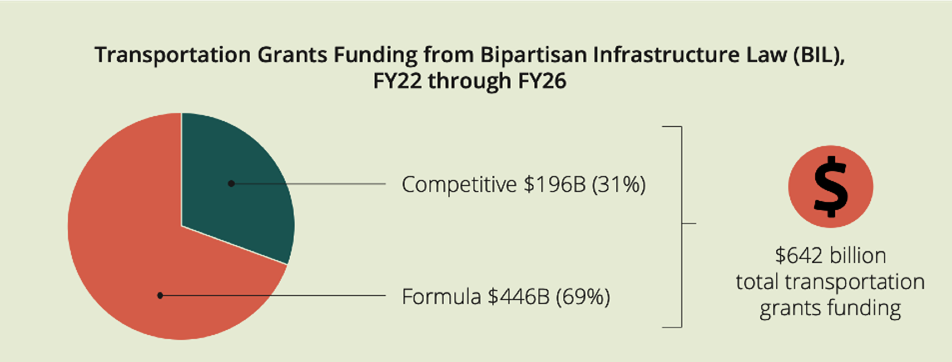

Federal transportation monies are distributed through various methods to the various federal highway and transit programs. First, the current Transportation Act, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), specifies dollar amounts to be distributed in each fiscal year (FY) covered by the Act. The IIJA authorizing legislation includes FY 2022 to FY 2026. Then, in its annual budget process, Congress specifies appropriations yearly to distribute funds to the US DOT. The USDOT then administers the authorized funding through two general funding methods –apportionment by formula and allocation, including discretionary grants. Additionally, when a transportation project receives federal funds, the local or state government is required to provide local funds as a match. The matching amount depends on the type of federal funding being received. Approximately 80% of project funds are federal, and 20% are matching funds. The “Project funding amount” in Figure 3.11 lists a local match of $51,000 for the “Replacement Midsize Cutaway” project. State DOTs are responsible for project oversight to ensure projects meet USDOT criteria and federal law. Local planning agencies (LPAs), like MPOs and other transportation agencies, are sub-recipients of the federal monies distributed to the state DOTs, who are the direct federal grantees.

Box. 3.2 Formula grants, what are they?

The most common non-discretionary opportunities offered by federal agencies are formula grants, which distribute funds to every recipient in a group (such as all 50 states) to accomplish the same purpose. These may also be known as federal-aid funds or formula funds. Formula grants are not competitive because the funding amount for each recipient is calculated based on specific parameters set by Congress, such as state population.

USDOT. (2024). Federal funding and financing: Grants. (https://www.transportation.gov/rural/grant-toolkit/funding-and-financing/grants-overview).In the public domain.

Box 3.3 What makes a grant “discretionary”?

Discretionary grants are grants that USDOT awards to eligible applicants usually through a competitive selection process. Eligible applicants vary based on the specific grant program but may include state, Tribal and local governments, transit providers, universities, research institutions, law enforcement agencies, nonprofit organizations, and others.

USDOT. (2024). Federal funding and financing: Grants. (https://www.transportation.gov/rural/grant-toolkit/funding-and-financing/grants-overview).In the public domain.

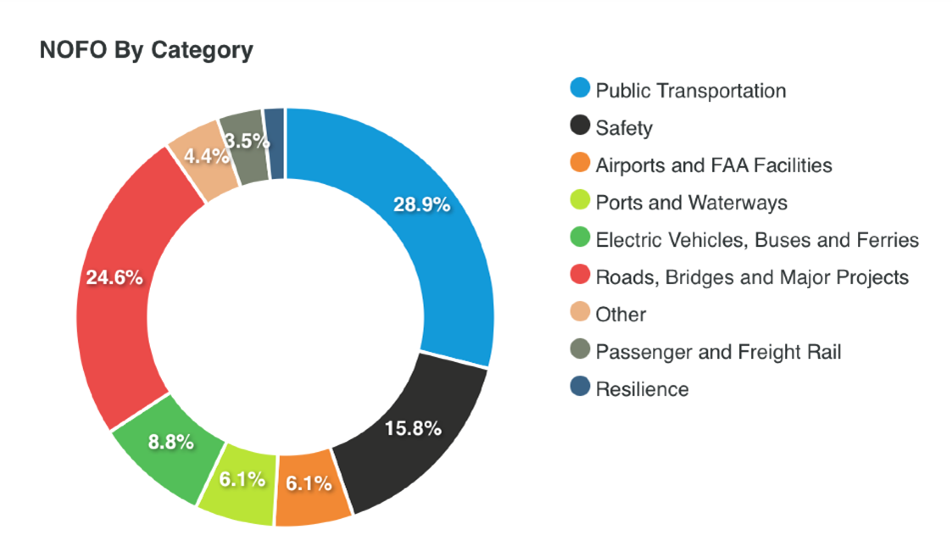

The discretionary grant funding program is competitive and administered by the FHWA and FTA. Discretionary grants are made available first by a “Notice of Funding Opportunity” (NOFO). Figure 3.12 illustrates that through the IIJA, approximately $200 billion in discretionary funds will be awarded the five-year period for programs focused on infrastructure and rural areas (nonmetropolitan areas), climate change and resilience, and equity for all roads.

At the regional and local level, MPO staff, in response to the NOFO, collaborate with local governing bodies and transportation agencies to select and submit project applications to the state DOT, where they are screened for eligibility. Each project application is evaluated based on criteria like cost-effectiveness, air quality benefits, local commitment, congestion reduction, and multimodal and social mobility benefits. Figure 3.13 illustrates programs, with calls for applications by announcing a notice of funding opportunity (NOFA) specifying eligibility, evaluation criteria, and program priorities.

Stakeholder Input

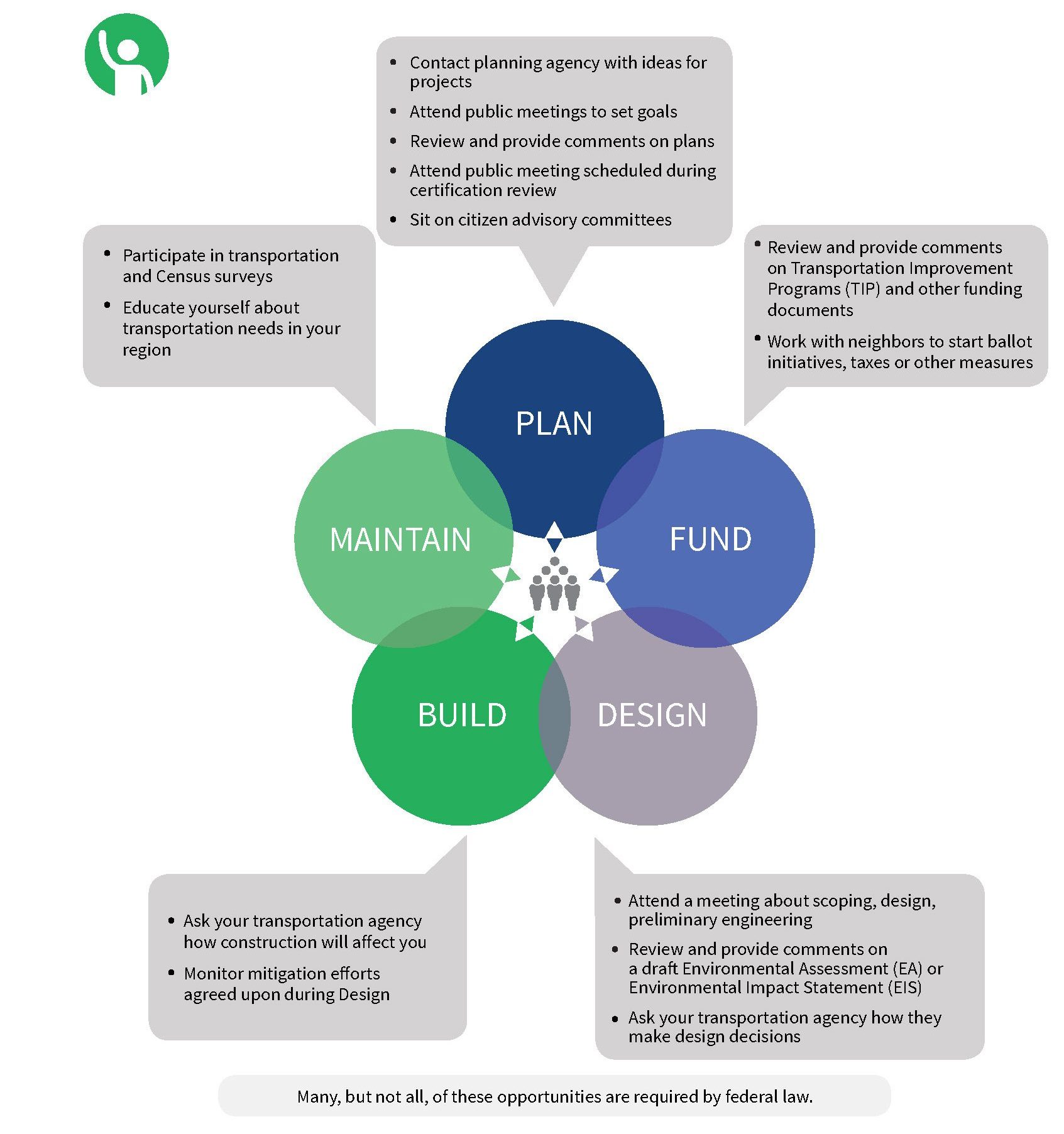

Since the 1962 Federal-Aid Highway Act and later in 1991 with ISTEA, public participation has been an essential and required activity in the transportation planning and programming process throughout its many stages of project development. As presented in Chapter Two, MPOs are obligated by Federal Law to create and regularly update a “Public Participation Plan” (PPP). This plan outlines specific activities undertaken by MPOs to collect, document and include public input in transportation plans and programs. Figure 3.14 displays the opportunities available to stakeholders for providing input during all stages of the process. Stakeholder input is at the center of transportation decisions.

The Federal Transit Administration in accordance with 23 CFR 450.316 indicates that an MPO’s PPP must include:

- “Adequate public notice of public participation activities;

- review and comment at key decision points in the development of the MTP and TIP; and

- multiple, accessible participation formats, including electronic and in-person” (FTA, 2023).

In compliance, MPOs summarize outreach activities and outcomes in their MTPs and TIPs and specify how they will conduct outreach and communication to ensure public participation. The MPO for the Dallas-Fort Worth area, NCTCOG, explains within its 2023-2026 TIP that:

“The Public Participation Plan provides measures for evaluating the effectiveness of NCTCOG Transportation Department’s public involvement activities regarding the transportation and air quality planning process. Evaluation helps staff understand how to better engage the public and allocate time and resources. Since 2019, NCTCOG has published a report summarizing the efforts for each fiscal year.” (NCTCOG, 2023, n.p.).

For an FHWA video on how transportation agencies are using virtual public involvement (VPI) tools, watch the video Virtual Public Involvement Outcomes:

Media 3.5 Federal Highway Administration USDOTFHWA. (2024, March 18). Virtual Public Involvement Outcomes. [Video]. https://youtu.be/7E_a7FkB-2o?feature=shared

Box 3.4 Community and stakeholder engagement are key to successful project delivery.

Additionally, the federal transportation acts mandate stakeholder engagement and involvement in the transportation planning and decision-making processes. Recently, the IIJA (Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021) furthers the importance of engagement as a measure of delivery:

Community and stakeholder engagement are key to successful project delivery.

Fostering open communication and collaboration with communities and stakeholders significantly increases the likelihood of delivering successful, impactful projects with societal benefits. Early and sustained community and stakeholder engagement are vital to ensuring the success of a project. Community involvement fosters a sense of ownership and inclusivity, aligning a project’s goals with the needs and values of those it affects. By engaging stakeholders early on, a project gains invaluable insights, allowing for better planning, risk mitigation, and more effective decision-making throughout the project lifecycle. This engagement also builds trust, encouraging cooperation and reducing potential conflicts. Moreover, stakeholders often bring diverse perspectives, expertise, and resources, contributing to innovative solutions and enhancing the project’s overall quality and sustainability.” (USDOT, Volpe Center, 2024, p. 2)

PART B: TRANSPORTATION PROJECT EVALUATION – “How did we do?”

In this last phase, the transportation agency evaluates and reports on progress in attaining targets and gauges the effectiveness of planning and investment decisions. Guided by Performance-Based Planning and Programming (PBPP), project outcomes are evaluated to determine the degree to which the transportation project meets policy goals and objectives and contributes to progress toward the successful implementation of performance targets. This information serves as feedback to the planning phase and helps to further refine goals, targets, measures, and future investment priorities as shown in Figure 3.15 Performance-based measures encompass five major functions:

-

- Defining goals: Performance measures aid in translating broad goals into measurable objectives.

- Monitoring performance: Metrics are utilized to track performance regularly, such as on a yearly or monthly basis.

- Setting targets: Metrics serve as a reference for establishing achievable targets.

- Informing decision-making: Metrics provide a basis for comparing various investment or policy options to support decision-making.

- Evaluating effectiveness: Metrics enable the assessment of whether projects and strategies have effectively contributed to achieving goals. (FHWA PBPP guidebook, 2018, p. 40).

Performance Management

In project selection, “performance could be defined as the execution of a required function” (Sinha & Labi, 2007, p. 21) and can be measured both qualitatively and quantitatively, indicating the extent to which a specific function is executed. For transportation projects, performance measures are influenced by two factors:

- The satisfaction of the transportation service user.

- The concerns of the system owner or operator and other stakeholders.

These performance measures must be identified at all stages of transportation project development. They are derived from a hierarchy of desired system outcomes, with effectiveness and equity (two of the “3 Es”) at the top of the hierarchy. At the next level, transportation network-level or system goals are identified in planning documents and integrated into all phases of project development. Each goal is supported by a set of objectives, and for each objective, specific performance measures are established (Sinha & Labi, 2007).

Table 3.2 shows examples of highway and transit performance measures, including a few of the national performance goals, while Figure 3.7 in Part A depicts how TXDOT measures and reports a specific measure for pavement condition to comply with both federal and state-level performance.

| GOAL | FACILITY OR CATEGORY | PERFORMANCE MEASURE(S) |

|---|---|---|

| ACCESSIBILITY | Roadway | Percentage of the population residing within 10 minutes or 5 miles of public roads |

| Access to and amount of transit | Percentage of the population with access to (or within a specified distance from) transit service | |

| Percent of the workforce that can reach the work site in transit within a specified period | ||

| MOBILITY | Travel speed | Average speed vs. peak-hour |

| Transit | Frequency of transit service | |

| Congestion | Hours of delay | |

| Amount of travel | Vehicle miles of travel (VMT) on highways | |

| SAFETY | Number of vehicle collisions | Fatality or injury rates per 100 million VMT |

| Number of pedestrians killed on highways | ||

| Transit collisions (injuries or fatalities) per VMT | ||

| QUALITY OF LIFE | Accessibility, Mobility | Percentage of motorists satisfied with travel times for work and other trips |

| Customer satisfaction with commute time | ||

| Customer perception of quality of transit service | ||

| Note: Adapted from “Transportation Decision Making: Principles of Project Evaluation and Programming,” by K. C. Sinha and S. Labi, (p. 14), 2007. | ||

THREE-Es of Transportation Evaluation

The 3E triangle (efficiency, effectiveness, and equity) of transportation project and program evaluation are applied throughout development of the transportation project. Project prioritization is a form of evaluation that incorporates the criteria represented by the 3E triangle – efficiency, effectiveness, and equity (Figure 3.16).

- Efficiency refers to the monetary value gained from a project relative to the investment required. Economic analysis is typically used to assess efficiency. However, it’s important to consider user costs and non-monetary or non-quantifiable performance measures when evaluating efficiency (Sinha & Labi, 2007). It is worth repeating that to assess the effectiveness of a transportation project, understanding the goals and objectives of the transportation project is essential. Goals and objectives are stated in the transportation planning documents such as the Metropolitan Transportation Plan (MTP). In deciding to select and invest in a project, programming first evaluates how well each project alternative will meet the program objective.

- The evaluation of effectiveness includes tangible and intangible measures, such as cost-benefit analysis and social well-being and aesthetic appeal (Sinha & Labi, 2007).

- Transportation equity is central to transportation planning as detailed in Chapter 4 of this book. This section highlights key equity considerations from the US DOT-FHWA perspective and provides examples of equity tools used by transportation agencies to analyze and evaluate projects’ potential disproportionate impacts on underserved populations.

Box 3.5 What is Equity in Transportation?

“Under Executive Order 13985 Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities (2021), the term “equity” means the consistent and systematic fair, just, and impartial treatment of all individuals, including individuals who belong to underserved communities that have been denied such treatment, such as Black, Latino, and Indigenous and Native American persons, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders and other persons of color; members of religious minorities; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) persons; persons with disabilities; persons who live in rural areas; and persons otherwise adversely affected by persistent poverty or inequality.”

The Federal Highway Administration states that equity in transportation “seeks fairness in mobility and accessibility to meet the needs of all community members. A central goal of transportation is to facilitate social and economic opportunities by providing equitable levels of access to affordable and reliable transportation options based on the needs of the populations being served, particularly populations that are traditionally underserved” (FHWA, 2024). Additionally, equity is one of the six goals of the US Department of Transportation’s FY 2022-2026 Strategic Plan. The 2023 update to the Equity Action Plan reinforces its mission to advance:

“Smart and inclusive transportation investments transform economies, connect people to opportunities and each other, and empower communities to build generational wealth for the future. The current transportation system distributes benefits and burdens that vary greatly by location due to historical and systemic patterns of disparity” (US DOT, 2023, p. 3).

In 2022, the USDOT established the Advisory Committee on Transportation Equity (ACTE) which reports directly to the Secretary of Transportation. The USDOT-FHWA Planning Portal on Transportation Equity https://www.planning.dot.gov/planning/topic_transportationequity.aspx emphasizes inclusive public participation and evaluation of benefits and burdens analysis in project development to assess impacts of proposed projects on traditionally underserved populations. Mitigation of negative impacts is expected to be addressed in the MPO’s TIP and State’s STIP. For more information, visit the USDOT-FHWA Planning Portal on transportation equity at The text covers equity in transportation, including Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and relevant Executive Orders. It discusses the roles of State DOTs, MPOs, and public transportation providers in promoting nondiscrimination and environmental justice in planning, as well as resources for further learning about equity in transportation at https://www.planning.dot.gov/planning/topic_transportationequity.aspx. The website covers equity in transportation, including Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and relevant Executive Orders. It discusses the roles of State DOTs, MPOs, and public transportation providers in promoting nondiscrimination and environmental justice in planning, as well as resources for further learning about equity in transportation.

Box 3.7 What role do State DOTs, MPOs, and public transportation providers play in incorporating nondiscrimination and environmental justice into transportation planning?

As the agency responsible for coordinating the transportation planning process, the State DOT or MPO must ensure that all segments of the population have been included in the planning process regardless of race, national origin, income, age, sex, or disability. State DOTs, MPOs, and public transportation providers must comply with agency-specific Title VI requirements when developing and implementing a Title VI Program.

EJ considerations are carried out through public participation and complementary benefits and burdens analysis at planning and project development stages to gauge potential impacts of proposed projects on traditionally underserved populations. The presence of disproportionately high and adverse impacts on EJ populations could necessitate mitigation. The results of these analyses are then incorporated into planning products such as the Long-Range Statewide Transportation Plan or Metropolitan Transportation Plan, Statewide Transportation Improvement Program or Transportation Improvement Program, Unified Planning Work Program, and Public Participation Plan.

Equity in Transportation, Coming Together on Transportation, USDOT-FHWA, TPCP 2024 (https://www.planning.dot.gov/planning/topic_transportationequity.aspx)

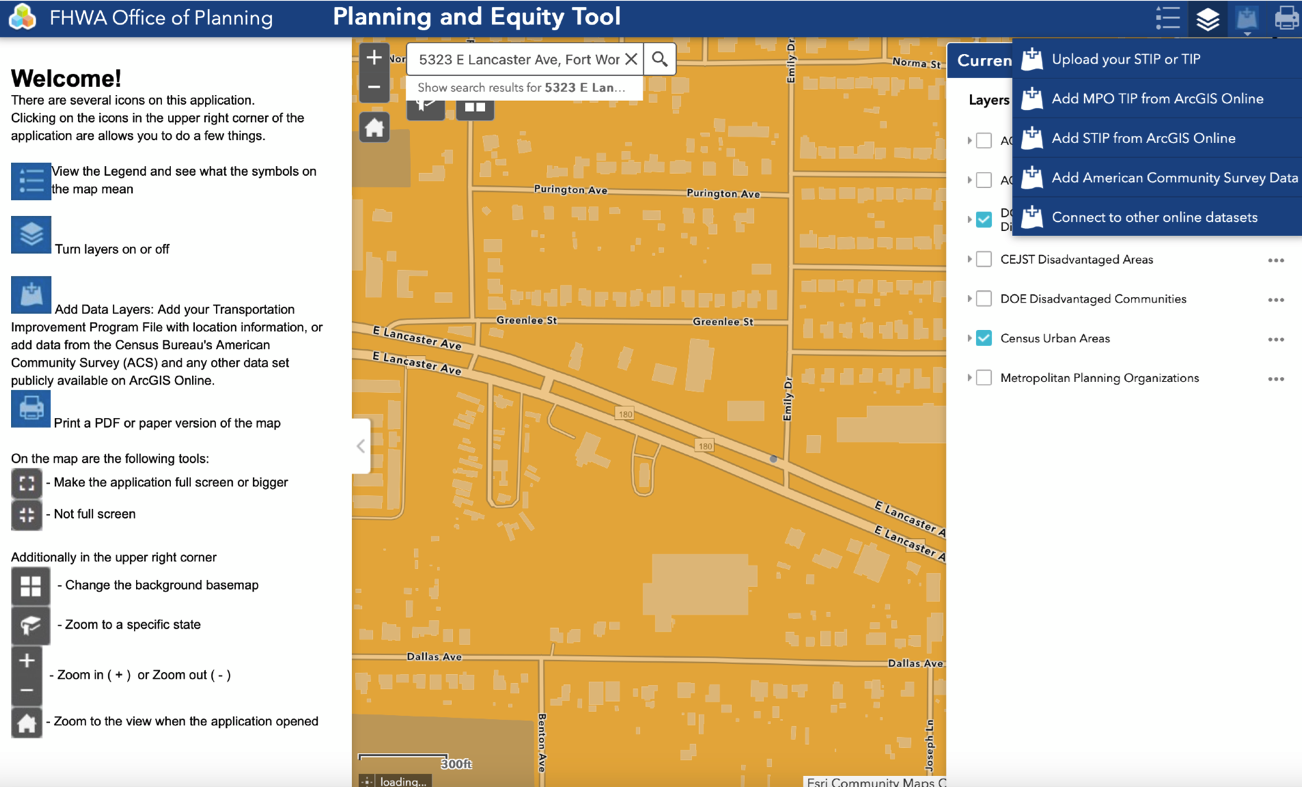

Equity Tools

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) Office of Planning provides an online Planning and Equity tool with recent data that helps decision-makers evaluate transportation program alternatives. Transportation agencies can upload their Transportation Improvement Programs (TIPs) or individual projects for evaluation using this tool which includes layer and data options from several sources, such as the White House Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), to support their Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool (CEJST). The screenshot below is from the FHWA Office of Planning Online GIS Planning and Equity tool.

Impacts of Transportation Projects

A critical aspect of project evaluation is the assessment of the impacts of existing or proposed transportation projects. Such impacts will vary depending on the scope, type, and size of the project. Project impacts are categorized into six main groups: technical, environmental, economic efficiency, economic development, legal, and community impacts (Sihna and Labi 2007).

- Technical Impacts include both primary motivations for transportation system improvements and the resulting effects. Considerations include facility condition improvements, vehicle operating costs, travel-time impacts, network mobility and accessibility, safety enhancements, inter-modalism, land-use patterns, and risk assessment.

- Environmental Impacts include ecological impacts of transportation systems, such as impacts on wetlands and ecology (biodiversity, fauna, and flora), air quality, water resources, noise pollution, and aesthetic impacts. Their assessment is typically a National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA) requirement.

Media 3.6 Federal Highway Administration USDOTFHWA. (2012, September 5). Overview of NEPA as applied to transportation projects. [Video].

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FTanW6keaAc

Media 3.7 Federal Highway Administration USDOTFHWA. (2016, October 24). Environmental assessment. [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S1x8rX7U3Hg

3. Economic Efficiency Impacts focus on the financial implications of transportation projects. Factors such as initial costs, life-cycle costs, and benefits are analyzed to assess economic efficiency.

4. Economic Development Impacts go beyond efficiency as these impacts involve evaluating the role of transportation projects in regional economic processes at different stages of production, such as employment growth.

5. Legal Impacts is a category that deals with the legal risks associated with transportation projects, including liability costs stemming from design, construction, or maintenance issues. With changing technologies like connected and automated vehicles, new legal considerations arise.

6. Community Impacts refer to the broader societal implications of transportation projects such as displacement of residents and businesses, barriers to walking and cycling, visual impacts, changes in accessibility and land use, impacts on community cohesion, and effects on property values. Impacts on archeological, historical, and cultural heritage community assets are also included in this group.

Media 3.8 Federal Highway Administration USDOTFHWA. (2016, October 24). The social environment. [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b3uEzq6Cccs

In addition to project characteristics, methodologies for assessing transportation project impacts also depend on the disciplines involved, such as economics, urban planning, engineering, operations research, environmental science, archeology, and historic preservation. The next section provides a snapshot of project evaluation in transportation with links to resources for further consultation.

Evaluation Methods

Evaluation methods of project impacts have ranged from traditional economics-based Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) to recent life-cycle-sustainability-based decision-making (Arshad et al., 2021), depending on policy, project performance objectives and agency practices. Other evaluation methods include:

- Contingent Valuation: Used in accessibility studies.

- Agent Modeling: Applied for safety in active transport and for assessing network capacity projects.

- Delphi Expert Evaluation Methods: Used for assessing environmental factors in public transportation projects.

- Multicriteria Analysis: Used in evaluation of quality-of-life impacts of active transportation.

- Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP): Applied for assessing racial equity in public transportation projects.

- Surveys and Focus Groups: Used for traffic management projects.

These methods were compiled in a comprehensive review of evaluation methods for “smart” transportation projects by (Džupka & Horvath, 2021). However, most non-traditional evaluation methods are still more commonly used by academic researchers in transportation than by practitioners.

Benefit/Cost Analysis (BCA)

Traditionally, the evaluation of transportation project impacts has relied on Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA), also known as Benefit Cost Analysis (BCA). The USDOT defines BCA as a “a systematic process for identifying, quantifying, and comparing expected benefits and costs of an investment, action, or policy. Common uses of BCA at DOT include regulatory impact analysis and policy analysis, as well as infrastructure project evaluation” (USDOT, 2024, n.p.). To assist applicants in preparing requests for discretionary funds, the USDOT provides a BCA spreadsheet template. https://www.transportation.gov/mission/office-secretary/office-policy/transportation-policy/benefit-cost-analysis-spreadsheet-template However, several state DOTs use alternative analytical tools to prioritize and evaluate transportation projects.

BCA Alternatives

In addition to BCA, other methods for project evaluation, such as contingent valuation and willingness to pay (WTP), focus on estimating monetary costs and benefits to recommend the alternative that maximizes return on investment or specific monetized benefits or burdens. However, for outcomes and impacts involving non-monetary costs and benefits and requiring stakeholder input, other evaluation methods like Participatory and Non-Participatory Multi-Criteria Analysis (MCA) are used as substitutes or complements to BCA.

MCA is the umbrella term for a number of related methods including multiple-criteria decision-making (MCDM), multiple-criteria decision analysis (MCDA), multi-objective decision analysis (MODA), multiple-attribute decision-making (MADM) or multi-dimensional decision-making (MDDM). Basically, MCA evaluates a plan or project by considering various project options or courses of action and the interplay between multiple, often contrasting, objectives, and different decision criteria and metrics (quantitative and qualitative) (Dean, 2022). In MCA, policy or project options are evaluated against multiple objectives for which a set of criteria has been identified. Each option’s performance is scored based on criteria that are weighted differently to reflect their importance. At the core of a multi-criteria method is the set of rules that define the options, objectives, criteria, scores, and weights and determine how these elements are used to assess, compare, screen, or rank options (Dean, 2022, p. 11).

MCA can be participatory involving multiple project stakeholders and experts unlike traditional methods where a single analyst might conduct the evaluation. This participatory approach is said to provide more comprehensive, transparent, and democratic evaluations.

For a detailed discussion consult Dean, M. 2022, Practical Guide to Multi-Criteria Analysis, Bartlett School of Planning, University College London DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.15007.02722

A comprehensive review of evaluation methodologies falls outside the scope of this book. For more in-depth and further exploration of this vast topic, the reader is encouraged to review some of the sources provided below:

- Rhouhani, O. M. (January 2019). Transportation Project Evaluation Methods/Approaches. Munich Personal RePEc Archive. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/91451/1/MPRA_paper_91451.pdf

- Chen, Williams, and Boyd. (2024). Evaluating system performance in multimodal transportation planning in multimodal planning. UTA PressBooks, OERtransport. Retrieved from https://uta.pressbooks.pub/oertransportmultimodalplanning/chapter/chapter-8-evaluating-system-performance/

- Cordero, F., LaMondia, J. J., & Bowers, B. F. (2024). Performance measure–based framework for evaluating transportation infrastructure resilience. Transportation Research Record, 2678(5), 601-616. https://doi.org/10.1177/03611981231190396

- Ustaoglu, E., & Williams, B. (2020). Cost-Benefit evaluation tools on the impacts of transport infrastructure projects on urban form and development. IntechOpen. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.86447 https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/68046 Free Open Source

- Project Assessment Tools Evaluation and Selection Using the Hierarchical Decision Modeling: Case Study of State Departments of Transportation in the United States. Authors: Rafaa I. Khalifa https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8173-9891 rafaa.khalifa@gmail.com and Tugrul U. Daim tugrul.u.daim@pdx.eduAuthor Affiliations. Publication: Journal of Management in Engineering Volume 37, Issue 1 https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000858.

- Zhang, L., Morallos, D., Jeannotte, K., & Strasser, J. (2012). Traffic Analysis Toolbox Volume XII: Work Zone Traffic Analysis–Applications and Decision Framework(No. FHWA-HOP-12-009). United States. Federal Highway Administration. Office of Operations. https://ops.fhwa.dot.gov/publications/fhwahop12009/index.htm#toc

- Konduri, K., Lownes, N., & Angueira, J. (2013). Analyzing the economic impacts of transportation projects(No. CT-2279-F-13-13). Connecticut. Dept. of Transportation. https://ctcase.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/CONNDOT_econ.pdf

- TRB Transportation Economics Committee. (2022). CBA: Transportation Benefit-Cost Analysis. Retrieved from https://sites.google.com/site/benefitcostanalysis/benefit-cost-analysis

- International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD). (2016). Environmental Impact Analysis (primer and manual) IISSD. Primer: retrieved from https://ctcase.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/CONNDOT_econ.pdf Manual: retrieved from https://www.iisd.org/learning/eia/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/EIA-Manual.pdf

Transportation programming is a crucial step in developing transportation networks. It involves prioritizing real-world projects based on established goals and objectives to respond to the question “what would it take” the transportation agency to achieve the strategic vision and goals laid out in its long-range metropolitan transportation plan (MTP)? In the programming process, Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs) document transportation project priorities as the Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) to prioritize projects for implementation by vetting them against USDOT’s performance-based planning framework, which emphasizes data-driven evaluation and decision-making. The MPO’s four-year final transportation improvement plan contains the list of projects that will be submitted for funding to the state DOT.

Efficiency, effectiveness, and equity serve as overarching criteria guiding the evaluation process, which asks the question “how did we do?” at every step including the one assessing the larger impacts of metropolitan transportation plans (MTP) and of implemented and built transportation improvement projects.

Project evaluation considers various impacts, including technical, environmental, economic efficiency, economic development, legal, and community impacts. Additionally, evaluation considers the project timeframe and purpose as a guide for determining appropriate evaluation methods to assess transportation projects’ effectiveness and efficiency. Traditional economic analysis, such as benefit/cost evaluation methods are still used, but alternative methods, such as multicriteria-analysis, address non-monetary costs and benefits in delivering services with community performance targets. Ultimately, transportation programming and evaluation aims to create a sustainable, equitable, and efficient transportation system that meets the evolving needs of communities and regions.

Chapter 3 quiz

3C process is the transportation process which stands for “continuing, comprehensive, and cooperative” and was first specified in the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1962. Its purpose is to be inclusive, focused on public input, and to prioritize regional planning of transportation projects.

3E triangle: Transportation project “alternatives are evaluated on the basis of the three E’s or 3E triangle: efficiency, effectiveness, and equity. These may be considered the overall goals of evaluation” (Since & Labi, 2007, p. 13).

Authorizing legislation: “Congress enacts legislation that establishes or continues the existing operation of a federal program or agency, including the amount of money it anticipates will be available to spend or grant to States, MPOs, and transit operators. Congress generally reauthorizes Federal surface transportation programs over multiple years, in effect authorizing subsequent Congressional action to make annual awards. The amount authorized, however, is not always the amount that ends up actually available” (TPCBP, 2018, n.p.).

Allocation: “The distribution of Federal-aid highway funding on any basis other than a statutory formula” (FHWA, 2017, p.19 )

Appropriation: “Annually, as set forth in authorizing legislation, Congress decides on the Federal budget for the upcoming fiscal year. As a result of the appropriation process, the amount appropriated to a federal program is often less than the amount authorized for a given year. The appropriation is the actual amount available to Federal agencies to spend or grant” (FHWA, 2017, p.19; TPCBP, 2018, n.p.).

Apportionment “describes appropriated funds, which come from selected Federal-aid programs, that are distributed among States and metropolitan areas (for most transit funds) using a formula provided by law. An apportionment is usually made on the first day of the Federal fiscal year (October 1), when funds become available for a State to spend in accordance with an approved STIP. In many cases, the State is the designated recipient for Federal transportation funds; in some cases, transit operators are the recipient” (TPCBP, 2018, n.p.).

Capital Improvement Plan (CIP) lays out the financing, location, and timing for capital improvement projects over several years. It typically consists of one or more capital improvement projects, which are financed through a capital budget. CIPs are important tools for local governments, allowing them to plan strategically for community growth and transformation. (Open Government, 2024).

Discretionary grants: Federal transportation funding made available by transportation and transit agencies through a competitive process in which projects are selected “based on program eligibility, evaluation criteria, and Departmental or program priorities” (USDOT, 2022, n.p.).

Financial Planning: “ Agencies use financial planning to take a long-range look at how transportation investments are funded and the possible sources of funds” (TPCBP, 2018, n.p.).

Financial Programming “ involves identifying available or expected funds and scheduling specific projects listed in the STIP, TIP, and MTP” (TPCBP, 2018, n.p.).

Fiscal Constraint: Estimates of costs and revenue sources “that are reasonably expected to be available to adequately operate and maintain Federal-aid highways (as defined by Title 23 U.S.C. 101(a)(5)) and public transportation (as defined by Title 49 U.S.C. Chapter 53).” “Making sure that a given program or project can reasonably expect to receive funding within the time allotted for its implementation” (FHWA Planning Glossary, 2022).

Flexible Funding as permitted by federal transportation legislation allows for the transfer of funds between certain highway and transit fund programs.

Goals and Objectives are essential to the strategic direction planned and programmed for the development of transportation projects and specify measurable outcomes that align with priorities.

Innovative Finance is a combination of techniques and specially designed mechanisms to supplement traditional financing sources and methods (IFS, 2024, n.p.).

Match: “Most Federal transportation programs require a non-Federal match. State or local governments must contribute some portion of the project cost at a matching level established by legislation. For many programs, the amount that State or local governments must contribute is 20 percent of the capital cost of most highway and transit projects” (TPCBP, 2018, n.p.).

Performance-Based Planning and Programming (PBPP) “is a strategic, data-driven approach to transportation decision-making that enables transportation planning agencies to efficiently allocate resources, maximize return on investments, and achieve desired performance outcomes while increasing accountability and transparency to the public) (TPCBP, n.d.).

Prioritization is the cooperative process by which transportation and transit agencies identify projects from the MTP to be included in the TIP.

Program of Projects, as defined by North Central Texas Council of Governments (NCTCOG), is a detailed list of upcoming transportation projects covering a period of at least four years.

Programming is the process of specifying and documenting transportation projects and matching those projects with available funds to accomplish agreed upon and stated needs (FHWA Planning Glossary, 2022).

Transportation Improvment Program (TIP) is a document prepared by regional transportation planning agencies cataloging prioritized transportation projects and available funding sources.

Transportation Performance Management is “a strategic approach that uses system information to make investment and policy decisions to achieve national performance goals” (FHWA, 2021, n.p.).

Performance target is a “quantifiable level of performance or condition, expressed as a value for the measure, to be achieved within a time period” (TPCBP, 2018, n.p.).

Performance measures “support objectives and are the basis for comparing alternative improvement, investment, and policy strategies, and tracking results” (TPCBP, 2018, n.p.). An expression based on a metric that is used to establish targets and to assess progress toward meeting the established targets.

REFERENCES

Arshad, H., Thaheem, M., Bakhtawar, B., & Shrestha, A. (2021). Evaluation of Road Infrastructure Projects: A Life Cycle Sustainability-Based Decision-Making Approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3743.

Johnston, R.A. (2004). The Urban Transportation Planning Process in S. Hanson and G Giuliano (Eds.), The geography of urban transportation, Guilford Press.

Dean, M. (2022). A practical guide to multi-criteria analysis. UCL: London, UK.

Džupka, P., & Horvath, M. (2021). Urban smart-mobility projects evaluation: a literature review. Theoretical and Empirical Researches in Urban Management, 16(4), 55-76.

Lee, D. B. (2000). Methods for evaluating transportation projects in the USA. Transport Policy, 7(1), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-070X(00)00011-1

Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). (2012). Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century (MAP-21) fact sheet. National goals and performance management measures, Title 1, 23 USC 150(b) [Fact Sheet]. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/map21/factsheets/pm.cfm#:~:text=A%20key%20feature%20of%20MAP,achievement%20of%20the%20national%20goals.

Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), Office of Policy and Governmental Affairs. (2017). Funding Federal-aid highways: Publication no. FHWA-PL-17_011. U.S. Department of Transportation. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policy/olsp/fundingfederalaid/FFAH_2017.pdf

Federal Highway Administration USDOTFHWA. (2016, August 22). Funding Basics and Eligibility [Video]. https://youtu.be/r0NBR4r3M7M

Federal Highway Administration USDOTFHWA. (2012, September 5). Overview of NEPA as applied to transportation projects. [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FTanW6keaAc

Federal Highway Administration USDOTFHWA. (2016, August 26). Projects and Statewide Planning. [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qNsdyhTlPqE

Federal Highway Administration USDOTFHWA. (2016, October 24). Environmental assessment. [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S1x8rX7U3Hg

Federal Highway Administration USDOTFHWA. (2016, October 24). The social environment. [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b3uEzq6Cccs

Federal Highway Administration USDOTFHWA. (2019, December 6). TPM Essentials: Performance Based Planning and Programming [Video]. https://youtu.be/nIyVE0MADZg

Federal Highway Administration USDOTFHWA. (2019, December 30). What is TPM and why does it matter? [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YyjW1Ua89Ug

Federal Highway Administration USDOTFHWA. (2024, March 18). Virtual Public Involvement Outcomes. [Video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qNsdyhTlPqE

Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). (2020). Building links to improve safety: How safety and transportation planning practitioners work together. U.S. Department of Transportation. https://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/tsp/fhwasa16116/saf_plan.pdf

Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). (2021). Transportation performance management. U.S. Department of Transportation. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/tpm/about/tpm.cfm

Federal Highway Administration. (2022). Planning glossary. Retrieved from https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/Planning/glossary

Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). (2022). The safe system approach. U. S. Department of Transportation. Retrieved from https://highways.dot.gov/sites/fhwa.dot.gov/files/2022-06/FHWA_SafeSystem_Brochure_V9_508_200717.pdf.https://www.planning.dot.gov/documents/RTPO_factsheet_master.pdf

Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), Innovative Finance Support. (2024). What is innovative surface transportation finance? US Department of Transportation. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ipd/

Federal Highway Administration & Federal Transit Administration (FHWA FTA). (2018). The transportation planning process: Key issues for transportation decision-makers, officials, and staff. U. S. Department of Transportation. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/planning/publications/briefing_book/

Federal Highway Administration & Federal Transit Administration (FHWA FTA). (2021). What is a regional transportation planning organization? [Fact sheet]. U. S. Department of Transportation. Retrieved from https://www.planning.dot.gov/documents/RTPO_factsheet_What_is_an_RTPO.pdf

Federal Highway Administration & Federal Transit Administration (FHWA FTA). (2023, January 2023). Federal transportation planning process [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/T2BCt39Ub1k?feature=shared

Federal Transit Administration (FTA). (2021). Safety performance targets guide. Retrieved from https://www.transit.dot.gov/regulations-and-programs/safety/public-transportation-agency-safety-program/safety-performance

Federal Transit Administration (FTA). (2023). Metropolitan, Statewide & Non-Metropolitan Planning. Retrieved from https://www.transit.dot.gov/regulations-and-guidance/transportation-planning/metropolitan-statewide-non-metropolitan-planning

North Central Texas Council of Governments (NCTCOG). (2024). 2025-28 Transportation Improvement Program. Retrieved from https://www.nctcog.org/trans/funds/tip/transportation-improvement-program-docs/2025-2028tip

North Central Texas Council of Governments NCTCOG. (2023). Public Participation Plan. Retrieved from https://www.nctcog.org/trans/involve/public-participation-plan

Open Government. (2024). What is a capital improvement plan? Retrieved from https://opengov.com/article/capital-improvement-plans-101/

Pima Association of Governments (PAG). (2024). FY 2025-2029 Transportation Improvement Program. Retrieved from https://pagregion.com/wp-content/docs/pag/2024/04/FY-2025-FY-2029-Draft-TIP-Document.pdf.

Richmond Regional Transportation Agency. (2022). Plan RVA 2017-2027 TIP. Retrieved from https://planrva.org/transportation/tip/.

Sinha, K. C., & Labi, S. (2007). Transportation decision making principles of project evaluation and programming. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/utarl/detail.action?docID=792589

Transportation Planning Capacity Building Program (TPCBP). (2018, webpage updated 2022). The transportation planning process: Briefing Book: Key issues for transportation decision-makers, officials, and staff (FHWA-HEP-23-001; DOT-VNTSC-FHWA-23-01). U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/planning/publications/briefing_book/fhwahep18015.pdf

US Department of Transportation (USDOT). (2017). Funding transportation toolkit. Retrieved from https://www.transportation.gov/sites/dot.gov/files/docs/ToolkitFinal2017.pdf

US Department of Transportation (USDOT). (2022). Overview of funding and financing at USDOT. Retrieved from https://www.transportation.gov/grants/dot-navigator/overview-funding-and-financing-usdot

US Department of Transportation (USDOT). (2023). 2023 equity action plan. Retrieved from https://www.transportation.gov/priorities/equity/2023-equity-action-plan

US Department of Transportation (USDOT). (2024). What is benefit-cost analysis (BCA)? https://www.transportation.gov/grants/dot-navigator/what-is-a-benefit-cost-analysis

US Department of Transportation (USDOT). (2024). Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) launchpad. Retrieved from https://billaunchpad.com/nofo

US Department of Transportation (USDOT), FHWA Office of Planning. (2024). Online GIS planning and equity tool. Retrieved from https://usdot.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=af1a590b45444e768402714efb148805

Wikibooks.org. (2017). Fundamentals of transportation/evaluation—Wikibooks, open books for an open world. https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Fundamentals_of_Transportation/Evaluation

Programming: "Priortizing proposed projects and matching those projects with available funds to accomplish agreed upon, stated needs" (FHWA Planning Glossary, 2022).

A Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) is a document prepared by regional transportation planning agencies cataloging prioritized transportation projects and available funding sources. "A document prepared by a metropolitan planning organization that lists projects to be funded with FHWA/FTA funds for the next one- to three-year period" (FHWA Planning Glossary, 2022). Note that "TIP" generally refers to the program document prepared by the MPO, while "STIP" refers to the "Statewide Transportation Improvement Program" prepared by the state Department of Transportation.

A Capital Improvement Plan (CIP) lays out the financing, location, and timing for capital improvement projects over several years. It typically consists of one or more capital improvement projects, which are financed through a capital budget. CIPs are important tools for local governments, allowing them to plan strategically for community growth and transformation. (Open Government, 2024).

Three Es: Also known as the 3E triangle.

Performance-Based Planning and Programming (PBPP) “is a strategic, data-driven approach to transportation decision-making that enables transportation planning agencies to efficiently allocate resources, maximize return on investments, and achieve desired performance outcomes while increasing accountability and transparency to the public” (TPCBP, n.d.).

Transportation Performance Management (TPM) is “a strategic approach that uses system information to make investment and policy decisions to achieve national performance goals” (FHWA, 2021, n.p.).

Goals and objectives are essential to the strategic direction planned and programmed for the development of transportation projects and specify measurable outcomes that align with priorities.

Prioritization is the cooperative process by which transportation and transit agencies identify projects from the MTP to be included in the TIP.

Financial planning: “Agencies use financial planning to take a long-range look at how transportation investments are funded and the possible sources of funds” (TPCBP, 2018, n.p.).

Financial programming “involves identifying available or expected funds and scheduling specific projects listed in the STIP, TIP, and MTP” (TPCBP, 2018, n.p.). "A short-term commitment of funds to specific projects identified in the regional Transportation Improvement Program" (FHWA Planning Glossary, 2022).

Program of Projects, as defined by North Central Texas Council of Governments (NCTCOG), is a detailed list of upcoming transportation projects covering a period of at least four years.

3C process is the transportation process which stands for “continuing, comprehensive, and cooperative” and was first specified in the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1962. Its purpose is to be inclusive, focused on public input, and to prioritize regional planning of transportation projects.

Fiscal constraint: Estimates of costs and revenue sources “that are reasonably expected to be available to adequately operate and maintain Federal-aid highways (as defined by Title 23 U.S.C. 101(a)(5)) and public transportation" (as defined by Title 49 U.S.C. Chapter 53). "Making sure that a given program or project can reasonably expect to receive funding within the time allotted for its implementation" (FHWA Planning Glossary, 2022).

Program of Projects, as defined by North Central Texas Council of Governments (NCTCOG), is a detailed list of upcoming transportation projects covering a period of at least four years.

Performance targets are “quantifiable levels of performance or condition, expressed as values for the measure, to be achieved within a time period” (TPCBP, 2018, n.p.).

Performance measures “support objectives and are the basis for comparing alternative improvement, investment, and policy strategies, and tracking results” (TPCBP, 2018, n.p.).

An expression based on a metric that is used to establish targets and to assess progress toward meeting the established targets.

Appropriation: “Annually, as set forth in authorizing legislation, Congress decides on the Federal budget for the upcoming fiscal year. As a result of the appropriation process, the amount appropriated to a federal program is often less than the amount authorized for a given year. The appropriation is the actual amount available to Federal agencies to spend or grant” (FHWA, 2017, p.19; TPCBP, 2018, n.p.).

Apportionment “describes appropriated funds, which come from selected Federal-aid programs, that are distributed among States and metropolitan areas (for most transit funds) using a formula provided by law. An apportionment is usually made on the first day of the Federal fiscal year (October 1), when funds become available for a State to spend in accordance with an approved STIP. In many cases, the State is the designated recipient for Federal transportation funds; in some cases, transit operators are the recipient” (TPCBP, 2018, n.p.).

Allocation: “The distribution of Federal-aid highway funding on any basis other than a statutory formula” (FHWA, 2017, p.19 )

Match: “Most Federal transportation programs require a non-Federal match. State or local governments must contribute some portion of the project cost at a matching level established by legislation. For many programs, the amount that State or local governments must contribute is 20 percent of the capital cost of most highway and transit projects” (TPCBP, 2018, n.p.).

The most common non-discretionary opportunities offered by federal agencies are formula grants, which distribute funds to every recipient in a group (such as all 50 states) to accomplish the same purpose. These may also be known as federal-aid funds or formula funds.

Formula grants are not competitive because the funding amount for each recipient is calculated based on specific parameters set by Congress, such as state population.

Discretionary grants: Federal transportation funding made available by transportation and transit agencies through a competitive process in which projects are selected “based on program eligibility, evaluation criteria, and Departmental or program priorities” (USDOT, 2022, n.p.).

3E triangle (aka three Es): Transportation project "alternatives are evaluated on the basis of the three E’s or 3E triangle: efficiency, effectiveness, and equity. These may be considered the overall goals of evaluation" (Since & Labi, 2007, p. 13).