4 Equity in Transportation Planning

CHAPTER OVERVIEW

Part A briefly highlights the body of US laws, executive orders, and administrative rules that frame the definition of transportation equity—a legacy of civil rights struggles against racist transportation planning and decision-making. These policies require the application of equity at all levels of transportation planning, programming, and project evaluation—the topic of the previous two chapters.

Part B delves into key equity and justice concepts used in transportation analysis and research, distinguishing horizontal and vertical equity and delving into the three types of justice—environmental and social, geographic (spatial), and procedural—necessary for a complete approach to transportation equity.

Part C explores procedural justice in the form of “meaningful” public involvement as proposed by scholars and new federal policy responding to the 2020 nationwide racial injustice protests. Implementing the policy, the US Department of Transportation requires meaningful public involvement in transportation planning and decision-making.

CHAPTER TOPICS

- Legal and Policy Framework for Transportation Equity

- Equity and Justice

- Achieving Procedural Justice in Practice

- Conclusion

- Quiz

- Glossary

- Acronyms

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Learning Objectives

- Describe the historical context and identify significant earlier and recent government directives framing transportation equity.

- Recognize the positive externalities (benefits) and negative externalities (burdens/costs) of the US car-centric system of transportation, explaining with examples, which population groups are the most advantaged and the most disadvantaged by the transportation system.

- Differentiate between justice and equity, horizontal and vertical equity, and between environmental, geographic, and procedural justice.

- Identify traditionally underserved populations and explain why and how transportation planners must include them in all phases of transportation planning.

INTRODUCTION

Contemporary transportation planning and programming emphasizes equity and the fair distribution of the positive and negative impacts of transportation decisions. The implementation of these decisions affects the spatial accessibility to opportunities such as travel to work and school, medical and social services, shopping, entertainment, and visiting family and friends. As introduced in Chapter One, accessibility—the ability to reach destinations or opportunities in the city or region—is a transportation system’s most crucial social and economic benefit (Martens, et al., 2012; Karner et al., 2023). A transportation system enables individuals, businesses, and institutions to participate in economic, social, cultural, and other essential activities for the well-being and prosperity of individuals and society.

Box 4.1 History – The Civil Rights Movement and Removing Barriers to Mobility

Rosa Parks is known as “the mother of the civil rights movement.” On December 1, 1955, she refused to give up her seat for a white man on a Montgomery, Alabama, bus. Parks was arrested for her defiance. After she challenged the local segregation ordinance and lost, Parks and others organized the Montgomery bus boycott: “For a little more than a year, we stayed off those busses. We did not return to using public transportation until the Supreme Court said there shouldn’t be racial segregation.” Parks and others lost their jobs, and she was harassed and threatened. The boycott raised an unknown clergyman named Martin Luther King, Jr., to national prominence and resulted in the US Supreme Court decision outlawing segregation on city buses. Learn more about Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycott.

FHWA (2022). Environmental justice history. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/environmental_justice/history/

In response, landmark federal legislation was enacted, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 banning discrimination based on race, color, or national origin, and presidential executive orders such as EO 12898 mandating all agencies receiving federal funds to identify and address disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects on minority and low-income populations. These policies have made transportation equity a requirement of all transportation agencies receiving federal dollars. Thus, understanding and addressing who benefits and who is disproportionately burdened by the costs of a car-centric transportation system—such as carless households, people with disabilities, and low-income individuals and households—has become not only a significant concern among transportation agencies and transportation planners but also a major responsibility.

PART A: LEGAL AND POLICY FRAMEWORK FOR TRANSPORTATION EQUITY

Due to the historical impact of racial segregation, urban renewal projects, and the racist siting of highways through low-income communities of color—particularly during the construction of the interstate highway system in the 1960s and 1970s, which destroyed and displaced many African American and immigrant communities (Aimen and Morris, 2012; Turner, 2022)—there is now a robust set of federal legislation and executive orders aimed at prohibiting discrimination based on race, color, national origin, ability, age, and gender. These include the 1964 Civil Rights Act’s Title VI, the 1987 Restoration Civil Rights Act, the Americans with Disabilities Act, and various presidential executive orders such as President Clinton’s EO 12898 (Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations) and President Biden’s EO 13985 (Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government).

Table 4.1 A, B, and C summarize the most important federal mandates (Acts and Executive Orders) on equity and the federal transportation administration’s (USDOT, FWHA, and FTA) implementation of these mandates as transportation equity regulations for planning agencies, transportation providers, and transportation federal funds recipients. Table 4.2 presents transportation equity guidance prepared by federal transportation agencies to guide compliance with their regulations.

| LAW | NOTES | REFERENCE |

|---|---|---|

| Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 | Prohibits race, color, and national origin discrimination in programs and activities receiving federal funds. | 42 U.S.C. §2000d et. Seq. |

| Age Discrimination Act of 1975 | Prohibits age discrimination in programs and activities receiving federal funds. | 42 U.S.C. §6101-6107 |

| Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987 | Clarifies relationships between Title VI and other more recent nondiscrimination law | 102 Stat. 28 |

| Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 | Prohibits discrimination against and requires equal opportunity for people with disabilities. | 42 U.S.C. §12101 |

| REGULATION | NOTES | REFERENCE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FTA/FHWA Joint Regulation for Statewide and Nonmetropolitan Transportation Planning: Metropolitan Transportation Planning regulations | Governs the development of metropolitan transportation plans (MTP) and programs for urbanized areas, long-range statewide transportation plans and programs, and the congestion management process. | 49 CFR Part 613 (FTA’s citation for the joint FTA/ FHWA regulations, found in total at 23 CFR Part 450) | |

| FTA/FHWA Joint Regulation for “Interested parties, public involvement, and consultation” | Requires MPOs and states to create a public participation plan establishing procedures for receiving and incorporating public input during the planning | 23 CFR 450.210 23 CFR 450.316 | |

| USDOT Title VI regulations | Implements Title VI compliance at the USDOT and its sub-agencies. | 49 CFR Part 21 | |

| FHWA Title VI program | Implements Title VI compliance at FHWA and its grantees. | 23 CFR Part 200 | |

| USDOT Americans with Disabilities Act regulations | Implements ADA compliance at the USDOT and its sub-agencies. | 49 CFR Parts 27, 37, 38, and 39 |

| EXECUTIVE ORDER | NOTES | REFERENCE |

|---|---|---|

| Executive Order 12898:

Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations |

Requires federal agencies to make achieving environmental justice part of their mission. | Clinton – Federal Register 59, no. 32 (1994): 7629–33. |

| Executive Order 13166:

Improving Access to Services for Persons with Limited English Proficiency |

Directs executive agencies to identify and provide needed services for persons with limited English proficiency. | Clinton – Federal Register 65, no. 159 (2000): 50121–22. |

| Executive Order 13330:

Human Service Transportation Coordination |

Establishes the “Interagency Transportation Coordinating Council on Access and Mobility” to coordinate efforts across multiple agencies that fund transportation services targeted at low-income people, older adults, and people with disabilities. | Bush, G.W. – Federal Register 69, no. 38 (2004): 9185–87. |

| Executive Order 13985:

Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government |

Directs the federal government to revise agency policies to account for racial inequities in their implementation. | Biden – Federal Register 86, no. 2021-01753 |

|

Notes:

|

||

This body of public policy mandates that the US Department of Transportation, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), and the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) implement these laws and executive orders as regulations and guidance for State Departments of Transportation (DOTs), Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs), transit authorities, and transportation providers. Collectively, these federal policies frame how transportation equity is officially defined:

Transportation equity refers to the way in which the needs of all transportation system users are reflected in the transportation planning and decision-making process. In particular, transportation equity focuses on the needs of those traditionally underserved by existing transportation systems, such as low-income and minority households, older adults, and individuals with disabilities. Transportation equity means that transportation decisions deliver equitable benefits to a variety of users and that any associated burdens are avoided, minimized, or mitigated so as not to disproportionately impact disadvantaged populations (FHWA and FTA 2018, p.23).

In implementing EO 13985 of 2021, the US Department of Transportation further defined transportation equity as quoted below for guidance efforts including the development of tools for measuring equity.

The term “equity” means the consistent and systematic fair, just, and impartial treatment of all individuals, including individuals who belong to underserved communities that have been denied such treatment, such as Black, Latino, and Indigenous and Native American persons, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders and other persons of color; members of religious minorities; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) persons; persons with disabilities; persons who live in rural areas; and persons otherwise adversely affected by persistent poverty or inequality.

The term “underserved communities” refers to populations sharing a particular characteristic, as well as geographic communities, that have been systematically denied the full opportunity to participate in aspects of economic, social, and civic life, as exemplified by the list in the preceding definition of “equity” (USDOT, 2021 https://www.transportation.gov/sites/dot.gov/files/2021-06/Public-Information-Session-Presentation-%28final%291.pdf )

The above definitions show that the notion of “underserved” and “disadvantaged” populations has broadened over the years. However, the foundational federal mandates for transportation equity guidance are rooted in Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Executive Order (EO) 12898 on environmental justice (EJ). Title VI prohibits discrimination based on race, color, and national origin, while EO 12898 directs all federal agencies to identify and address disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects on minority and low-income populations.

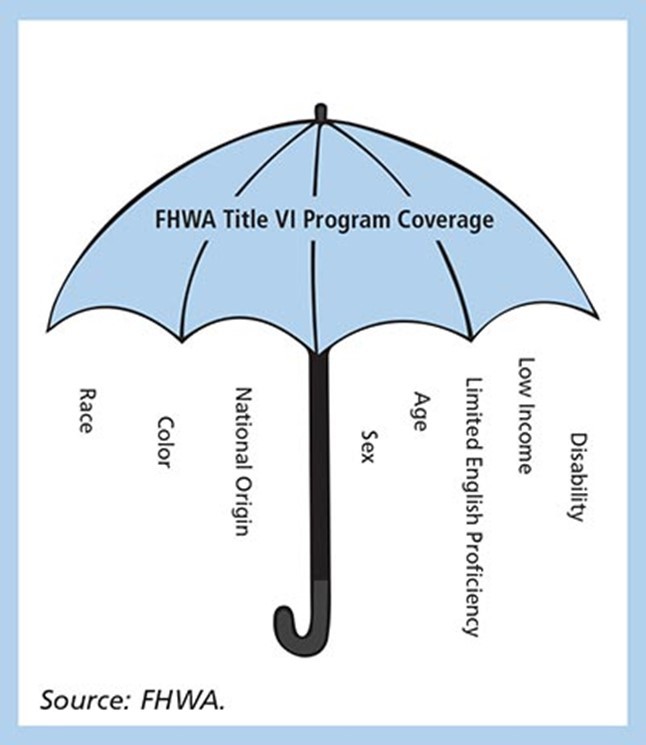

Recognizing gaps and overlaps between these mandates, the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) expanded their Title VI guidance for all State DOTs, MPOS and transportation agencies receiving federal funding. This updated guidance extends the scope of protected classes beyond the original Title VI statute to include sex, age, disability, limited English proficiency, and low-income status.

“Although the Title VI statute protects persons from discrimination solely on the basis of race, color, and national origin, the FHWA Title VI Program includes other nondiscrimination statutes and authorities under its umbrella, including E.O. 12898, ensuring that FHWA’s fund recipients do not discriminate based on income, sex, age, disability, or limited English proficiency as well” (Kragh, et al., 2016, n.p.), as illustrated in Figure 4.1.

Media 4.1 Minnesota Department of Transportation (2023, June 30). Transportation equity – A State DOT’s perspective [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R4yi0gCGSYU

PART B: EQUITY AND JUSTICE

Equity Concepts

In its most general sense, equity refers to the just and fair distribution of costs and benefits across a society. In transportation, Litman’s (2024) equity classification into horizontal and vertical dimensions has been widely used since the 1990s:

Horizontal equity, based on the principle of equality or fair share, refers to the distribution of costs and benefits among individuals and groups in similar circumstances (ability and wealth).

Vertical equity, based on the principle of distributive justice, refers to the distribution of cost and benefits among individuals or groups differing in circumstances (ability or wealth) and who are structurally disadvantaged.

Litman (2024) further classifies and groups, under the horizontal and vertical dimensions, five equity types summarized in Table 4.3 in terms of goals, indicators and strategies. Box 4.3 provides a description of each equity type.

| EQUITY TYPE | GOAL | INDICATORS | STRATEGIES |

|---|---|---|---|

| HORIZONTAL | |||

| Fair Share | Each person receives a comparable share of public resources | Per capita share of public resources (money, road space, etc.) | Multimodal transport planning. Comprehensive impact analysis. Least-cost funding. |

| Externalities (Costs) | Travelers minimize and compensate for external costs. | Infrastructure costs, congestion, crash risk, and pollution that travelers impose on other people. | Minimize and compensate for external costs. Favor resource-efficient modes. |

| VERTICAL | blank cell | blank cell | blank cell |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Social Inclusion |

Transportation systems provide basic mobility to disadvantaged groups. | Quality of travel for people with disabilities and other special needs. Disparities between groups. |

Favor inclusive modes and accessible community development. |

|

Affordability |

Lower-income households can afford basic mobility. |

Transportation costs relative to incomes. Quality of affordable modes. | Favor affordable modes and housing in high-access areas. |

| Social / Environmental Justice | Policies address structural inequities. |

Whether organizations address biases such as racism and classism. | Identify and correct structural inequities, past wrongs.

Affirmative action. |

Note: Adapted from “Evaluating transportation equity guidance for incorporating distributional impacts in transport planning,” by T. Litman, 2024, p. 11, https://www.vtpi.org/equity.pdf. In the public domain.

Box 4.2 Types of Transportation Equity by Todd Litman (2024)

1. A Fair Share of Resources

Horizontal equity requires that people with similar needs and abilities receive similar shares of resources and bear similar shares of costs. It implies that consumers should “get what they pay for and pay for what they get” unless subsidies are specifically justified.

2. External Costs

External costs, such as infrastructure subsidies, congestion delays, crash risk, and pollution that one person imposes on others are horizontally inequitable. Fairness requires minimizing or compensating for these costs.

3. Inclusivity – Vertical Equity Regarding Mobility Need and Ability

Vertical equity requires that transportation systems serve travelers with mobility

impairments. This supports multimodal planning, to accommodate people who cannot or should not drive, plus universal design (also called accessible and inclusive design), which ensures that transportation facilities and services accommodate all users, including those with disabilities and other special needs.

4. Affordability – Vertical Equity Regarding Income

Vertical equity assumes that public policies should favor economically disadvantaged groups, and ensure that lower-income people can afford basic mobility. Policies are called progressive if they favor disadvantaged groups and regressive if they harm such groups. This definition supports affordable mode improvements, affordable housing in multimodal neighborhoods, plus special transportation services and discounts for lower-income groups.

5. Social Justice

Social justice (also called environmental justice) objectives address structural social inequities such as racism, sexism, and unfair disparities. It is usually addressed by establishing affirmative action programs and targets, employee training, and procedural justice (the decision-making process is transparent and fair)

Evaluating transportation equity guidance for incorporating distributional impacts in transport planning, 29 May 2024, Victoria Transport Policy Institute, https://vtpi.org/equity.pdf

Frameworks for Transportation Justice

While transportation equity is defined and administered by the federal government and its transportation agencies, as detailed in Part A, transportation justice is a broader concept defined and advanced by transportation academics and advocacy groups outside of government agencies. These scholars emphasize “justice” over “equity,” aiming for transformative change rather than mere reform. They critique equity-focused approaches for their mixed and often ineffective record in addressing past transportation injustices, largely due to racialized and tokenistic institutional legacies that have hindered meaningful involvement of disadvantaged communities in transportation planning and decision-making processes (Karner et al., 2020).

Echoing Bullard et al. (2004), the concept of transportation justice includes not only concerns with distributive justice (implied in vertical equity) but also procedural justice, which involves inclusive and fair transportation planning and decision-making processes. According to Bullard et al. (2004), disparate transportation outcomes can be categorized into three broad types: environmental and social, geographic (spatial), and procedural. This section explores each of these concepts, highlighting the most salient transportation justice approaches and frameworks.

Environmental Justice

Environmental Justice (EJ), along with environmental racism, “refers to environmental policies, practices or directives that differentially affect or disadvantage (whether intentionally or unintentionally) individuals, groups of communities based on race or color” (Bullard, 2002, p. 35). From the perspective of the previously detailed federal mandates, EJ refers to avoiding, preventing, and mitigating racial, ethnic, and other social sources of inequality in the distribution of positive and negative environmental impacts as defined by law. This underscores the notion of “protected classes”—low-income, race, ethnicity, national origin, limited English proficiency, sex, and disability groups—legally protected from disproportionate impacts of transportation policies, projects, and programs, which requires their effective meaningful involvement in transportation planning, programming, and decision making.

For instance, low-income and/or carless households are burdened by a car-centric transportation system and limited from accessing vital economic and social opportunities. These groups are forced to depend on alternative modes of transportation (transit, walking, or biking), which are underfunded in comparison with public investments devoted to automobile infrastructure. Often, low-income communities of color, where careless households predominate, have disproportionately borne the environmental burdens (noise and air pollution) and health harms and hazards associated with nearby six-lane highways or transportation facilities they may not get to use (Bullard et al., 2004; Sanchez et al. 2003).

Social Justice

Social Justice includes social equity which concerns the distribution of amenities (benefits) and disamenities (burdens/costs) across transportation groups and asks: Are they equally distributed? It refers to the principle of social inclusion in the distribution of transportation benefits, ensuring that all groups have equal access to the opportunities transportation provides. However, the distributive justice approach recognizes that the social and economic system’s inequalities reproduce structural disadvantaged groups. This social justice approach addresses inequities and barriers to transportation access and mobility options to promote broader social equity. Individuals with disabilities, frail seniors, low-income-female-headed households, carless households, and low-income neighborhoods without public transit service or with public transit service that does not connect to needed opportunities (jobs, health care, groceries) are examples of groups and places left out from full participation in transportation mobility and accessibility benefits.

Geographic or spatial equity

Geographic or spatial equity concerns the place or neighborhood’s (local) and regional (e.g., rural vs. urban, or central city vs. suburban) accessibility to opportunities. It asks whether transportation decisions disproportionately favor certain locations over others in terms of services, facilities and infrastructure, resources and investments, and access to employment centers and other vital and essential places in the city or region (Bullard, 2004). Accessibility and mobility frameworks pertain to this equity type, and as introduced in Chapter One, they directly relate to land use and transportation planning analysis and decisions.

Travel demand models have been the cornerstone of spatial accessibility analysis, but they are biased towards automobile travel. Until recently, the availability of new real-time data sources from partnerships between transit agencies and IT companies has made possible more accurate travel demand models for transit, walking, and biking (Karner et al., 2023). Despite an overwhelming body of accessibility approaches and measures, there is no standard approach for assessing the spatial equity outcomes of transportation systems. Based on a comprehensive review of approaches Guo et al., (2020) identified an overarching three-step framework characteristic of most accessibility equity assessments.

Accessibility Equity Framework

Accessibility Equity Framework focuses on the population groups for whom the benefits of transportation are evaluated using spatial units such as census tracts, block groups or traffic analysis zones (TAZ). The first step in the framework involves identifying the populations for horizontal or vertical equity; the second step quantifies the transportation outcomes of interest such as accessibility (benefit); and the third step compares the accessibility outcomes to determine inequalities in their distribution. The approach described below varies slightly in terms of horizontal or vertical equity.

- Identifying the population. For horizontal equity, which treats the population as homogeneous, the distribution of accessibility is evaluated (irrespective of demographic differences) based on the spatial location of residence of the population. Vertical equity, on the other hand, evaluates the distribution of accessibility for subgroups identified based on race, ethnicity, education and income or disadvantaged criteria such as unemployment rate, deprivation index, mobility need and ability, etc. Each population subgroup’s data—typically measured as the percentage of each subgroup residing within each spatial census or TAZ unit—is employed to calculate the accessibility measure or transportation benefit.

- Quantifying the benefit or outcome. Among the various methods for measuring the accessibility outcome or benefit of a transportation system, “reachability” metrics gauge the ability of a zone’s population to reach activities or destinations in all other zones in the city or study area subjected to a monetary and/or time budget. The analysis counts how many other zones a subpopulation from a zone can reach within a time or monetary limit. The larger the number of reachable zones within that limit, the larger the accessibility enjoyed by the population in that zone. As highlighted in Chapter One of this book, the accessibility of a zone or place is equal to “the sum of its accessibility to any other zone” in the city or study area (Guo et al., 2020, p. 5). Since the accessibility between two zones decreases as the travel cost (time or money) increases, this “impedance in accessibility” function can be captured by either a cumulative accessibility function (Golub and Martens, 2014; El Geneidy et al., 2016) or an accessibility negative exponential function (Santana Palacios and El-Geneidy, 2022) (Guo et al., 2020, p. 5).

- Determining inequality. Gap analysis tabulating and GIS mapping the accessibility results for each zone’s population allows us to manually and visually compare the transportation system’s horizontal or vertical equity performance. For horizontal equity, the distribution of accessibility for each zone is plotted for the whole city or study area displaying the accessibility of all zones for one population irrespective of demographic characteristics; for vertical equity, maps of the distribution (by zone) of the subgroup of interest (e.g., carless population) are compared with maps of the distribution of the system’s (e.g., transit) accessibility measure for all subgroup’s zones. This approach has been used to identify gaps in equity between transit need (zones with high shares of careless households) and supply (transit accessibility for those zones). To quantify gaps (between need and supply) for horizontal equity, simple descriptive measures of dispersion like variance and standard deviations have been used, while for vertical equity, correlation and multivariate regression analysis exploring for instance, the relationship between transit accessibility and race and household factors such as education and income have been also utilized. Additionally, inequality indices, for example, the Gini index for horizontal equity, and for vertical equity, the Atkinson index, which uses an “aversion inequality” adjustment to weight benefits for those at the low end of the benefit distribution (Guo et al., 2020 p. 8).

Note: This framework relates to one of several conceptual accessibility approaches. For further details on accessibility concepts and measures for all levels of expertise and an in-depth treatment of the subject, including examples from MPOs and State DOTs, see Karner et al. (2022). For other approaches outside academia, see also Karner, A., Levine, K., Alcorn, L., Situ, M., Rowangould, D., Kim, K., & Kocatepe, A. (2022). Accessibility measures in practice: a guide for transportation agencies. Transportation Research Board. https://doi.org/10.17226/26793

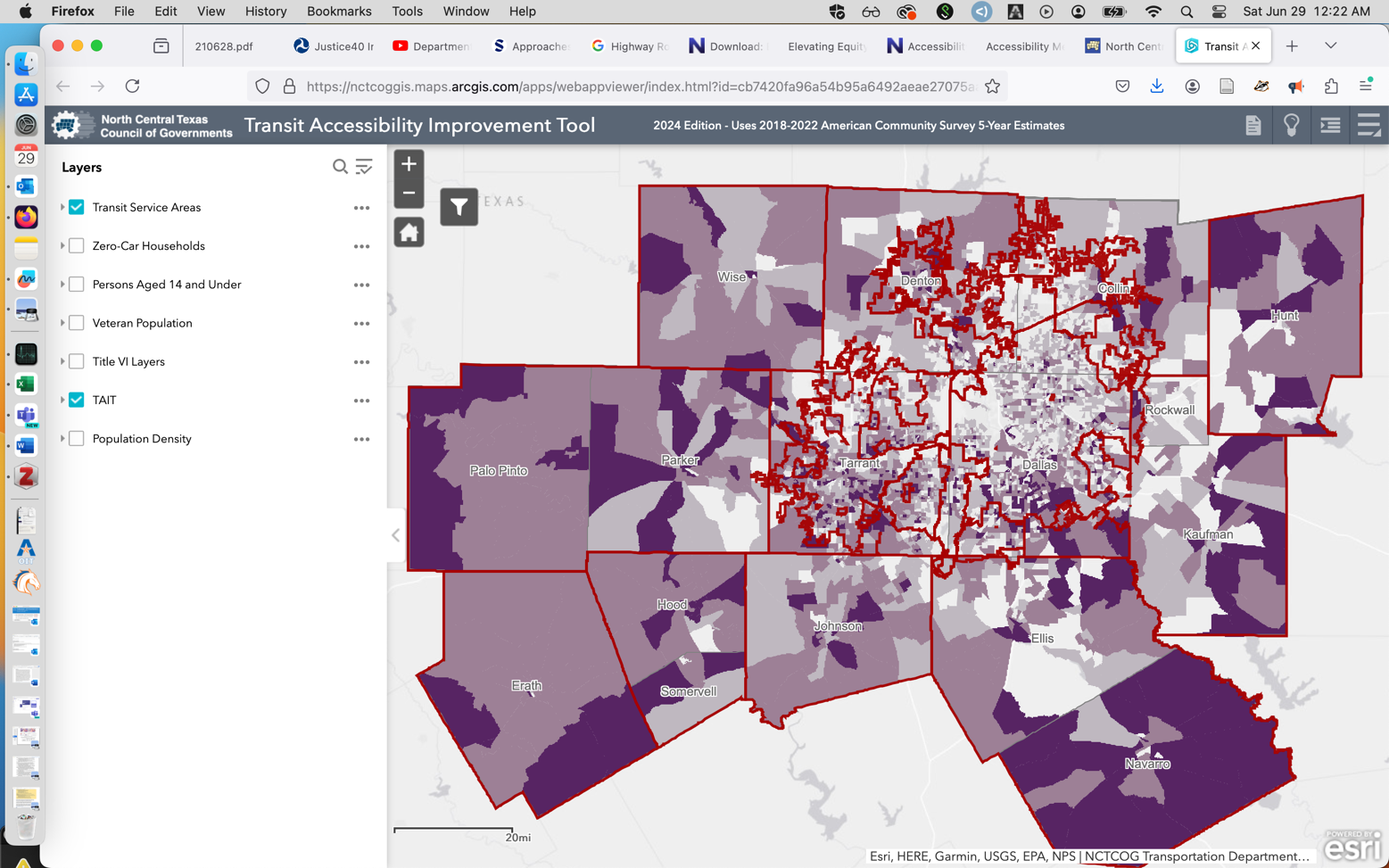

Box 4.3 Accessibility example: North Central Texas Council of Governments (NCTCOG).

A practical application of the accessibility equity framework is the Transit Accessibility Improvement Tool, which was developed by the NCTCOG to help identify communities facing transportation disadvantages.

“The Transit Accessibility Improvement Tool (TAIT) identifies communities who face transportation disadvantages and may have a greater potential need for public transit. This is done by identifying US Census block groups with concentrations of residents who are below poverty, living with disabilities, or age 65 and over.”

Note: “This is a GIS-based tool that’s available on our website. You don’t have to have GIS to use it, but if you do have GIS, you can download the data and work with it yourself. It overlays three layers: elderly people, people with disabilities, and low-income populations to identify where there may be the greatest transit need. We have additional layers of existing transit service areas. You can compare where there’s a need and where there isn’t service available. We have additional demographic layers if folks want to consider those or use them for an equity analysis. . . . Separately, we use similar data to conduct an equity analysis of our long-range transportation plan, where we look at things like number of jobs accessible within 15 to 30 minutes by auto [or other transportation modes]. We look at those for protected populations versus non-protected populations (protected being environmental justice populations) . . . and then we compare whether the projects in the long-range plan result in an equitable outcome.” (NCTCOG interviewee in Kramer et al., 2023, p. B-12).

In addition to the above TRB source, USDOT has released Transportation Data and Equity Hub (Hub), a one-stop shop that offers tools, metrics, and data to analyze transportation accessibility and the impacts of the transportation system on communities. Explore the data, maps, and other equity-related data visualization tools at Explore the Data, Variable Explorer or Tools, Maps and Apps. USDOT invites users to make their own maps using these data and tools.

Procedural Justice

Procedural justice asks if the transportation planning and decision-making process is transparent and fair and conducted with meaningful involvement of stakeholders and affected communities (Bullard et al., 2004). The emphasis here is “meaningful” to the community, which in the EJ context means a fair process that empowers affected community stakeholders and residents to voice their interests and concerns and to participate in decisions about a transportation project or activity that will affect their environment, safety or health (Aimen and Morris 2012, p. 5-1).

PART C: ACHIEVING PROCEDURAL JUSTICE IN PRACTICE

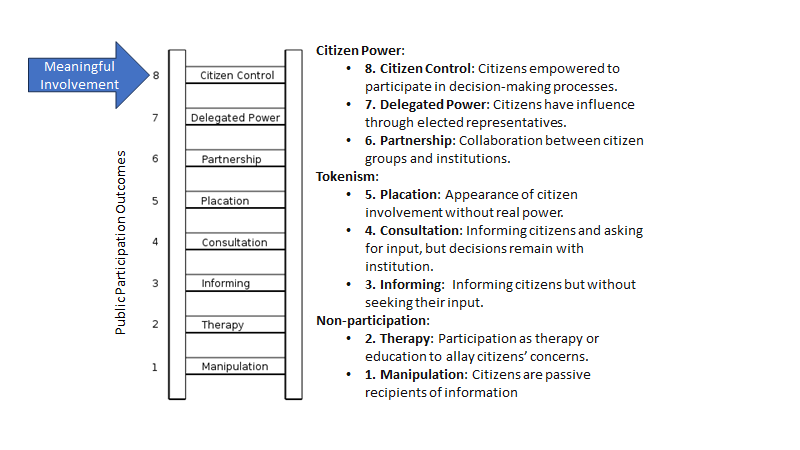

As discussed in the previous section, achieving equity in transportation requires procedural justice through meaningful public involvement. Despite the Federal Highway Administration’s (FHWA) institutionalization of public involvement since its 1969 3-C guidance, which mandated citizen participation in all phases of the planning process (from goal setting to analysis of alternatives) (Weiner 2008, p. 60), public participation has often been limited and superficial.

With a few exceptions, public participation was mostly tokenistic, restricted to hearings that merely announced projects and involved consultation or placation as defensive tactics against public opposition, particularly during the periods of urban renewal and interstate highway construction. This led Arnstein (1969) to develop her ladder of public participation, with “citizen control” representing the highest level of community involvement.

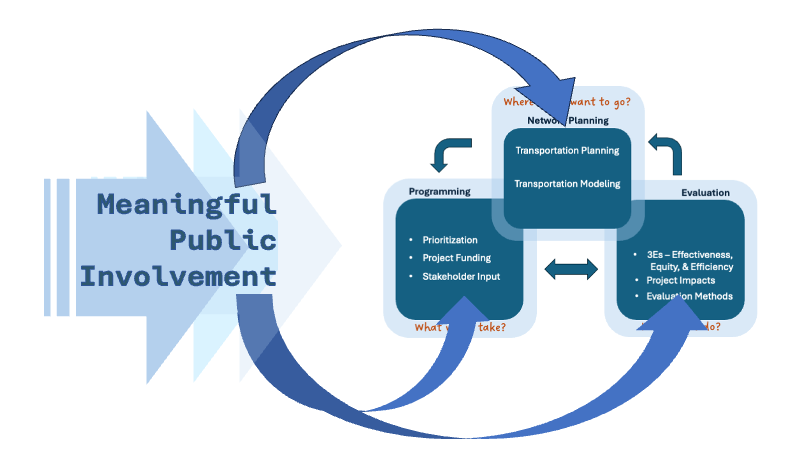

In other words, meaningful public involvement, which allows for the possibility to shape the outcomes of the planning process, is essential for achieving procedural justice and just outcomes in transportation equity (Figure 4.4).

As Karner and Marcantonio (2018) observe, despite decades of legally required public involvement methods in transportation planning, these efforts have often fallen short of meeting the meaningful engagement standard. This shortfall is partly due to the time and costs required to build a transportation agency’s capacity for meaningful participation. Additionally, the priority needs of underserved communities often differ significantly from those typically pursued by public agencies (e.g., cost-effectiveness, positive benefits in a cost-benefit framework, or Pareto optimality) (p. 114).

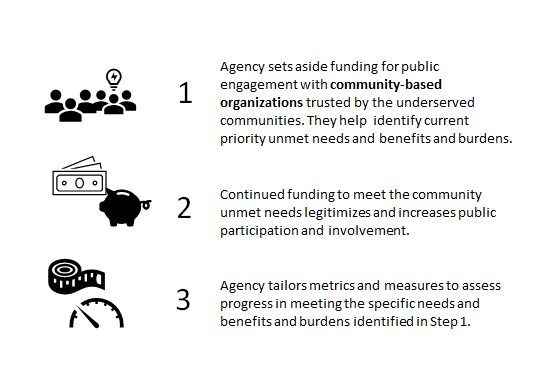

Based on research and successful public participation cases in California, Karner and Marcantonio (2018) have proposed a model for transportation equity that can be applied at the planning, programming, and project levels (presented in Chapters 2 and 3). Their three-step model for a funded, community-led decision-making process (Figure 4.5) consists of:

- Identifying current priority unmet needs in disadvantaged communities: This involves providing a dedicated fund to facilitate meaningful engagement. To achieve authentic involvement, agencies should rely on and fund community-based organizations that have established trusted relationships with underserved communities such as low-income, transit-dependent, senior, and limited English proficiency populations. This step also includes determining current benefits and burdens.

- Allocating funding to meet the needs identified in step 1: This significantly increases the salience and relevance of public involvement for underserved communities and their participation (p. 119).

- Tailoring metrics and measuring progress: This involves tracking the specific changes identified by the community in step 1 to ensure accountability and effectiveness.

Meaningful Public Involvement and Equity: From the Federal to Regional and Local Transportation Agencies

In the aftermath of the 2020’s nationwide mass demonstrations for racial justice, ignited by the killing of George Floyd, President Biden issued Executive Order 13985: “Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government.” In response to the EO, the above three-step and other public participation models, analyses, and methods (Sanchez et al., 2003, Innes & Booher 2004, Aimen and Morris 2012, Triplett 2015), have begun to make inroads into transportation at the federal level as USDOT, for the first time, has made equity a department-wide strategic goal institutionalizing equity across the department’s policies and programs. Along with expanding access, the USDOT’s 2023 updated Equity Action Plan underscores the department’s commitment to:

- continuously provide resources to embed equity, civil rights, and social justice initiatives into the Department’s decision-making processes, including meaningful public involvement, and

- ensure that equity is a core part of the Department’s mission and culture (USDOT, 2023, p.20).

Media 4.2 US DOT. (2022, July 13). U.S. Department of Transportation – Equity action plan [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/H-iQCr-xyhY?feature=shared

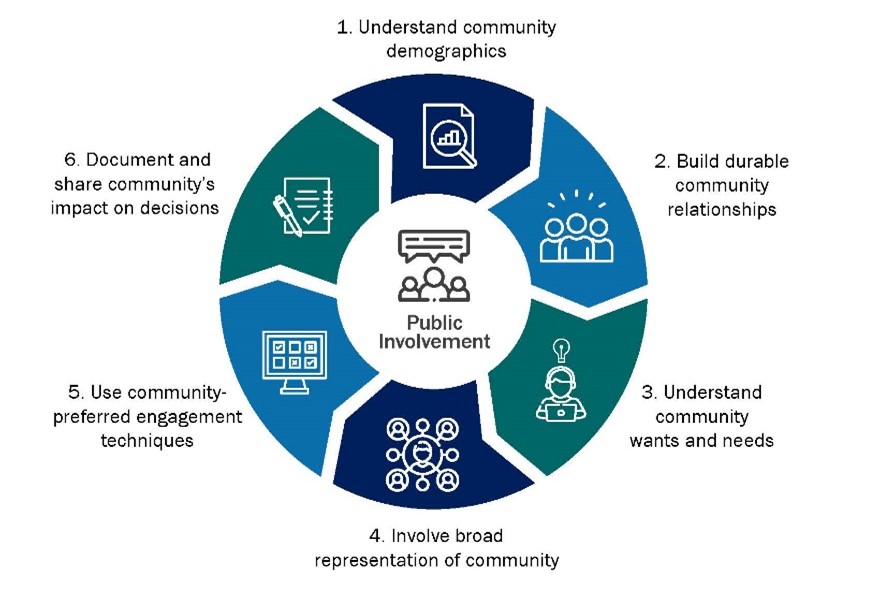

These initiatives aim to strengthen current FHWA and FTA requirements of federal funds recipients—State DOTs, MPOs, transit authorities, and transportation providers— to imbue meaningful public involvement in all transportation planning phases from strategic planning to programming and decision making. In its latest guidance to help achieve this, the USDOT’s Promising Practices for Meaningful Public Involvement in Transportation Decision-Making (2023) provides practical advice to practitioners across all modes of transportation on ways to strengthen public involvement including how grant application budgets and program funds can be used for this purpose.

Harking back to Chapters Two and Three, the left side of the Planning, Programming, and Project Evaluation figure labeled “Data & Public Involvement & Stakeholder Input” under this guidance implies meaningful public involvement that translates into effective, actionable input into the three phases of transportation decision making: planning, programming and project evaluation Figure 4.6.

Involving Underserved Populations

Traditionally, public involvement practices have been top-down, one-size-fits-all, focused on promoting attendance with little consideration for effectively identifying and locating underserved populations and leveraging opportunities for public involvement capable of influencing outcomes. To fill this gap, USDOT’s (2023) guidance defines meaningful public involvement as a process that “proactively seeks full representation from the community; considers public comments and feedback; and incorporates that feedback into a project, program, or plan” (USDOT 2024, p. 18). It further underscores five features of public involvement consisting of:

- Understanding the demographics of the affected community.

- Building durable relationships with diverse community members outside of the project lifecycle to understand their transportation wants and needs.

- Proactively involving a broad representation of the community in the planning and project lifecycle.

- Using engagement techniques preferred by, and responsive to the needs of, these communities, including techniques that reach the historically underserved.

- Documenting how community input impacted the final projects, programs, or plans, and communicating with the affected communities how their input was used (USDOT, 2023, p. 5).

While the US Department of Transportation’s new directives are decisive steps for improving transportation equity, through procedural justice, establishing a dedicated revenue stream to meet community needs and forging effective partnership with community-based organizations, as outlined in Karner and Marcantonio’s three-step model, may prove to be the litmus test for furthering a more complete equity approach to transportation.

Box 4.4 Underserved Populations

Who are the traditionally underserved populations?

The traditionally underserved can be defined as those specifically identified in Executive Order 12898 on Environmental Justice—that is, low-income populations and minority populations including Hispanics/Latinos, African Americans/Blacks, Asians/Pacific Islanders, and Native Americans—as well as other populations recognized in Title VI and other civil rights legislation and executive orders, including those with limited English proficiency such as the foreign-born, low-literacy populations, seniors, Americans with disabilities (including those who are visually and hearing impaired) as well as in transportation legislation, such as transit-dependent populations.

[. . .] The traditionally underserved include persons with low educational attainment (i.e., those without a high school degree), the unemployed or the underemployed who may have less access to opportunities. Single mothers, undocumented workers, immigrants with limited English proficiency, the homeless, substance abusers, and domestic violence victims are vulnerable populations. Women, elderly, physically or mentally impaired persons, late-night transit-dependent workers, or youth may have limited mobility options, particularly complex travel needs (e.g., trip-chaining and transit transfers), or have excessively difficult commutes in terms of time or risks to personal safety to reach jobs or other opportunities because of their isolation (i.e., distance or time-of-day). Transportation solutions need to be combined with other land use planning, social service, education, and health care initiatives to alleviate persistent disadvantages experienced by all persons in need.

[“Underserved’ and other synonymous terms] share a recognition that some individuals and groups experience a persistent inability to meet basic needs, access opportunities to improve their circumstances, or influence decision-makers because of their social position, lack of resources, or powerlessness. The terms encompass both protected and unprotected classes and groups under the nation’s existing civil rights laws and other laws, regulations, and executive orders.

Aimen and Morris. (2012). NCRHP Report 170, p. 1-2.

CONCLUSION

Two approaches to equity in transportation were discussed. The first approach stems from federal government responses to civil rights struggles against segregation in public transit and the discriminatory placement of freeways, especially interstate highways, which led to the widespread displacement of low-income communities of color. Landmark legislation such as Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Executive Order 12898 (Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority and Low-Income Populations, 1994), along with various other federal acts and executive orders, have defined transportation equity. This government-led framework, administered by the USDOT and its branches like the FHWA and FTA, shapes our understanding of transportation equity in practice and administration.

The second approach originates from transportation scholars, researchers, and practitioners who study transportation equity within or outside the government-led framework. They focus on the many groups disadvantaged by the US car-centric transportation system, drawing on three types of justice: environmental and social, geographic, and procedural. This chapter briefly discussed these equity and justice concepts, noting a recent convergence of government-led and academic approaches on procedural justice. The 2020 civil rights protests, sparked by the murder of George Floyd, led to Executive Order 13985 (Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government, 2021).

In implementing this order, the USDOT’s Equity Action Plan aims to institutionalize meaningful public involvement to achieve equity within the department and among the agencies it funds, including regional planning agencies, public transit authorities, and any other transportation organizations receiving federal funds. For transportation planners, these developments are significant as their organizations are now expected to address transportation equity through meaningful public involvement of underserved communities during the planning, programming, and project evaluation phases of decision-making.

QUIZ

Chapter 4 quiz

GLOSSARY

Accessibility negative exponential function describes how the likelihood or ease of accessing opportunities decreases exponentially with increasing travel time, distance, or cost. In this function, the accessibility to a destination diminishes rapidly as the travel impedance (time, distance, or cost) increases, reflecting a more realistic decay in accessibility over longer distances or higher costs.

Cumulative accessibility function measures the total number of opportunities (such as jobs, services, or amenities) that can be reached within a given threshold of travel time, distance, or cost from a specific location. It aggregates accessibility by counting all reachable destinations that fall within the specified limit, providing an overall assessment of the ease with which individuals can access essential resources and opportunities from their starting point.

Distributive justice: is concerned with the fair allocation of resources, benefits, and burdens within a society, ensuring that all individuals receive a just share based on specific principles. Under John Rawl’s Difference Principle a distribution (of benefits) is just if it maximizes the benefit for the group enjoying the least benefit. It aims to reduce inequalities by improving the well-being of the least advantaged members of society.

Equity action plan is a strategic document outlining specific goals, actions, and measures designed to promote fairness and inclusion by addressing and rectifying disparities experienced by underserved or marginalized groups. It aims to ensure access to opportunities, resources, and benefits across all segments of society.

Impedance in accessibility refers to any factor that hinders or restricts the ease and speed of movement between locations. It can include physical barriers, distance, time, cost, and other obstacles that affect the ability to reach desired destinations such as jobs, services, and amenities. Impedance plays a critical role in determining the overall accessibility of a location by influencing the effort required to travel from one place to another.

Locational disadvantaged communities are groups of people who experience limited access to essential services, opportunities, and resources due to their geographic location, often leading to social, economic, and health disparities.

Meaningful public involvement refers to the active and genuine participation of community members in decision-making processes, where their input is considered seriously and has a tangible impact on outcomes.

Negative externality: A cost imposed on others when an economic activity occurs. For example, a highway that is often congested with cars emitting pollution affects the health and environment of nearby residents who may not even own cars to use the highway.

Positive externality: A benefit received by others when an economic activity occurs. For example, a new light rail system increases the neighborhood’s property values and accessibility by transit.

Structurally disadvantaged refers to groups or communities that experience systemic barriers and inequalities embedded within societal, economic, and political institutions. These disadvantages arise from entrenched practices, policies, and norms that perpetuate disparities in access to resources, opportunities, and rights, often based on characteristics such as race, gender, socioeconomic status, or geographic location.

Structural inequality refers to systematic disadvantages that affect certain groups due to societal structures, policies, and practices, leading to unequal access to resources, opportunities, and rights based on characteristics such as race, gender, socioeconomic status, or other factors.

REFERENCES

Aimen, D. and Morris, A. (2012) Practical approaches for involving traditionally underserved populations in transportation decisionmaking. NCHRP Report 170, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/22813.

Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224.

Bhuyan I.A., Chavis C., Nickkar A. and Barnes P. (2019). GIS-based equity gap analysis: Case study of Baltimore Bike Share Program. Urban Science, 3(2):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci3020042

Cantilina, K., Daly, S. R., Reed, M. P., & Hampshire, R. C. (2021). Approaches and barriers to addressing equity in transportation: experiences of transportation practitioners. Transportation Research Record, 2675(10), 972-985. https://doi.org/10.1177/03611981211014533

Bullard, R. D. (2002) Confronting environmental racism in the twenty-first century. Global Dialogue, Nicosia, 4 (1), Winter, 34-48.

Bullard, R. D., Johnson, G. S., and Torres, A. O. (2004). Highway robbery: transportation racism & new routes to equity. South End Press.

El-Geneidy, A., Levinson, D., Diab, E., Boisjoly, G., Verbich, D., & Loong, C. (2016). The cost of equity: Assessing transit accessibility and social disparity using total travel cost. Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice, 91, 302–316.

FHWA (2015) Federal Highway Administration environmental justice reference guide. https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/50875

FHWA & FTA (2018) The transportation planning process briefing book. FHWA-HEP-18-015. https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/planning/publications/briefing_book/fhwahep18015.pdf

Golub, A., & Martens, K. (2014). Using principles of justice to assess the modal equity of regional transportation plans. Journal of Transport Geography, 41, 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2014.07.014

Guo, Y., Zhiwei, C., Stuart A., Li, X. and Zhang, Y. (2020). A systematic overview of transportation equity in terms of accessibility, traffic emissions, and safety outcomes: From conventional to emerging technologies. Perspectives, 4 (March). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100091

Innes, J.E. & Booher, D.E. (2004). Reframing public participation: Strategies for the 21st century. Planning Theory & Practice, 5(4)419-436. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/content/qt4gr9b2v5/qt4gr9b2v5.pdf

Karner, A., Levine, K., Alcorn, L., Situ, M., Rowangould, D., Kim, K., and Kocatepe, A. (2022). Accessibility measures in practice: a guide for transportation agencies. Transportation Research Board. Report 1000. https://doi.org/10.17226/26793

Karner, A., Levine, K, Dunbar, J., and Pendyala, R (2023). Practical measures for advancing public transit equity and access. FTA Report No. 0249. U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Transit Administration. https://www.transit.dot.gov/research-innovation/practical-measures-advancing-public-transit-equity-and-access-report-0249

Karner, A., London, J., Rowangould, D., and Manaugh, K. (2020). From transportation equity to transportation justice: Within, through and beyond the state. Journal of Planning Literature, 35(4), 440–459. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412220927691

Karner, A. and Marcantonio, R.A. (2018). Achieving transportation equity: Meaningful public involvement to meet the needs of underserved communities. Public Works Management & Policy, 23(2) 105–126. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1087724X17738792?journalCode=pwma

Kragh, B.C., Nelson, C., and Groudine C. (2016). Environmental justice: The new normal for transportation. Public roads, March/April, Vol. 79, No. 5, FHWA-HRT-16-003. https://highways.dot.gov/public-roads/marchapril-2016/environmental-justice-new-normal-transportation

Litman, T. (2024). Evaluating transportation equity. Guidance for incorporating distributional impacts in transportation planning. 29 May 2024. Victoria Transport Policy Institute. https://www.vtpi.org/equity.pdf

Martens, K., Golub, A. and Robinson, G. (2012). A justice-theoretic approach to the distribution of transportation benefits: Implications for transportation planning practice in the United States. Transportation research part A: policy and practice, 46 (4), May 2012, 684-695. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0965856412000055

Santana Palacios, M. and El-Geneidy, A. (2022). Cumulative versus Gravity-Based Accessibility measures: Which one to use?” Findings, February. https://doi.org/10.32866/001c.32444. https://findingspress.org/article/32444-cumulative-versus-gravity-based-accessibility-measures-which-one-to-use

Sánchez, T. W., Stolz, R., and Ma, J. S. (2003). Moving to equity: Addressing inequitable effects of transportation policies on minorities. Cambridge, MA: The Civil Rights Project at Harvard University. https://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/metro-and-regional-inequalities/transportation/moving-to-equity-addressing-inequitable-effects-of-transportation-policies-on-minorities/sanchez-moving-to-equity-transportation-policies.pdf

TRB – Transportation Research Board (2024). Elevating equity in transportation decision making recommendations for federal competitive grant programs. TRB Special Report 348. National Academy of Sciences. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/27439/elevating-equity-in-transportation-decision-making-recommendations-for-federal-competitive-grant-programs

Triplett, K. L. (2015). Citizen voice and public involvement in transportation decision-making: A model for citizen engagement. Race, Gender & Class, 22(3–4), 83–106. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26505351

Turner, D.E. (2022). Equity in Transportation. Public roads, 86 (1), Spring. FHWA-HRT 22-003. https://highways.dot.gov/public-roads/spring-2022/hottopic

USDOT (2021). Transportation equity at USDOT, information session. US Department of Transportation, June 25, 2021 https://www.transportation.gov/sites/dot.gov/files/2021-06/Public-Information-Session-Presentation-%28final%291.pdf

USDOT (2023). Equity action plan 2023 update. September 2023. https://assets.performance.gov/cx/equity-action-plans/2023/EO_14091_DOT_EAP_2023.pdf

USDOT (2024). USDOT promising practices for meaningful public involvement in transportation decision-making. Training, March 6, 2024. https://www.transportation.gov/sites/dot.gov/files/2024-03/Public%20Involvement%20Guide%20Training%20Presentation_March6_for%20posting.pdf

Weiner, E. (2008). Urban transportation planning in the United States: History, policy, and practice. 3rd Edition. Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-0-387-77152-6

Positive externality: A benefit received by others when an economic activity occurs. For example, a new light rail system increases the neighborhood's property values and accessibility by transit.

Negative externality: A cost imposed on others when an economic activity occurs. For example, a highway that is often congested with cars emitting pollution affects the health and environment of nearby residents who may not even own cars to use the highway.

Distributive justice is concerned with the fair allocation of resources, benefits, and burdens within a society, ensuring that all individuals receive a just share based on specific principles. Under John Rawl’s Difference Principle a distribution (of benefits) is just if it maximizes the benefit for the group enjoying the least benefit. It aims to reduce inequalities by improving the well-being of the least advantaged members of society.

Structurally disadvantaged refers to groups or communities that experience systemic barriers and inequalities embedded within societal, economic, and political institutions. These disadvantages arise from entrenched practices, policies, and norms that perpetuate disparities in access to resources, opportunities, and rights, often based on characteristics such as race, gender, socioeconomic status, or geographic location.

Structural inequities refers to systematic disadvantages that affect certain groups due to societal structures, policies, and practices, leading to unequal access to resources, opportunities, and rights based on characteristics such as race, gender, socioeconomic status, or other factors.

Impedance in accessibility refers to any factor that hinders or restricts the ease and speed of movement between locations. It can include physical barriers, distance, time, cost, and other obstacles that affect the ability to reach desired destinations such as jobs, services, and amenities. Impedance plays a critical role in determining the overall accessibility of a location by influencing the effort required to travel from one place to another.

Cumulative accessibility function measures the total number of opportunities (such as jobs, services, or amenities) that can be reached within a given threshold of travel time, distance, or cost from a specific location. It aggregates accessibility by counting all reachable destinations that fall within the specified limit, providing an overall assessment of the ease with which individuals can access essential resources and opportunities from their starting point.

Accessibility negative exponential function describes how the likelihood or ease of accessing opportunities decreases exponentially with increasing travel time, distance, or cost. In this function, the accessibility to a destination diminishes rapidly as the travel impedance (time, distance, or cost) increases, reflecting a more realistic decay in accessibility over longer distances or higher costs.

Equity action plan is a strategic document outlining specific goals, actions, and measures designed to promote fairness and inclusion by addressing and rectifying disparities experienced by underserved or marginalized groups. It aims to ensure access to opportunities, resources, and benefits across all segments of society.

Meaningful public involvement is defined as a process of intentionally programmed outreach to representatives of the entire community and inclusion of the community’s needs and vision into the transportation planning and programming documents (US DOT, 2022).