45 Introduction

Chapter Authors: Karishma Chatterjee, Damla Ricks, Diane Waryas Hughey

Learning Objectives

- Describe the process of communication.

- Define technical and professional communication.

Defining Communication

We cannot not communicate in the presence of another person (Watzlawick & Beavin, 1967). This is a well-known idea among scholars and practitioners in the field of communication. Even if a person decides not to speak, others will interpret or assign meaning to the act of “not speaking.” So, what is communication? There are many definitions of communication. We offer two such definitions because they encompass ideas applicable to the different contexts in which we communicate. Professors Griffin, Ledbetter, and Sparks (2015) define communication as “the relational process of creating and interpreting messages that elicit a response” (p. 6). Professor Rothwell (2019) summarizes communication as a “transactional process of sharing meaning with others” (p. 12).

Both definitions include concepts such as transactional, messages, relationships, process, meaning, and response. Let’s review each of these terms next.

Communication is transactional means each person is both a sender and receiver simultaneously of messages (Rothwell, 2019). As you speak, you receive feedback from other listeners. You may even adjust how you speak or what you are saying based on the non-verbal cues’ listeners send.

Communication is a process, which means it is dynamic or often changing between and among people. For example, when you first meet someone called Joe at work or in the classroom, it is normative to ask each other questions to get to know each other. However, you may choose to share information with Joe at first and over time decide not to share information with Joe.

Communication is often seen as a relational process (Griffin et al., 2015). This is because human communication takes place between at least two people, and it may affect or change the nature of the relationship. You thought you were becoming friends with Joe who begins to snap at you when you approach each other. You then decide to stop trying to form a friendship with Joe.

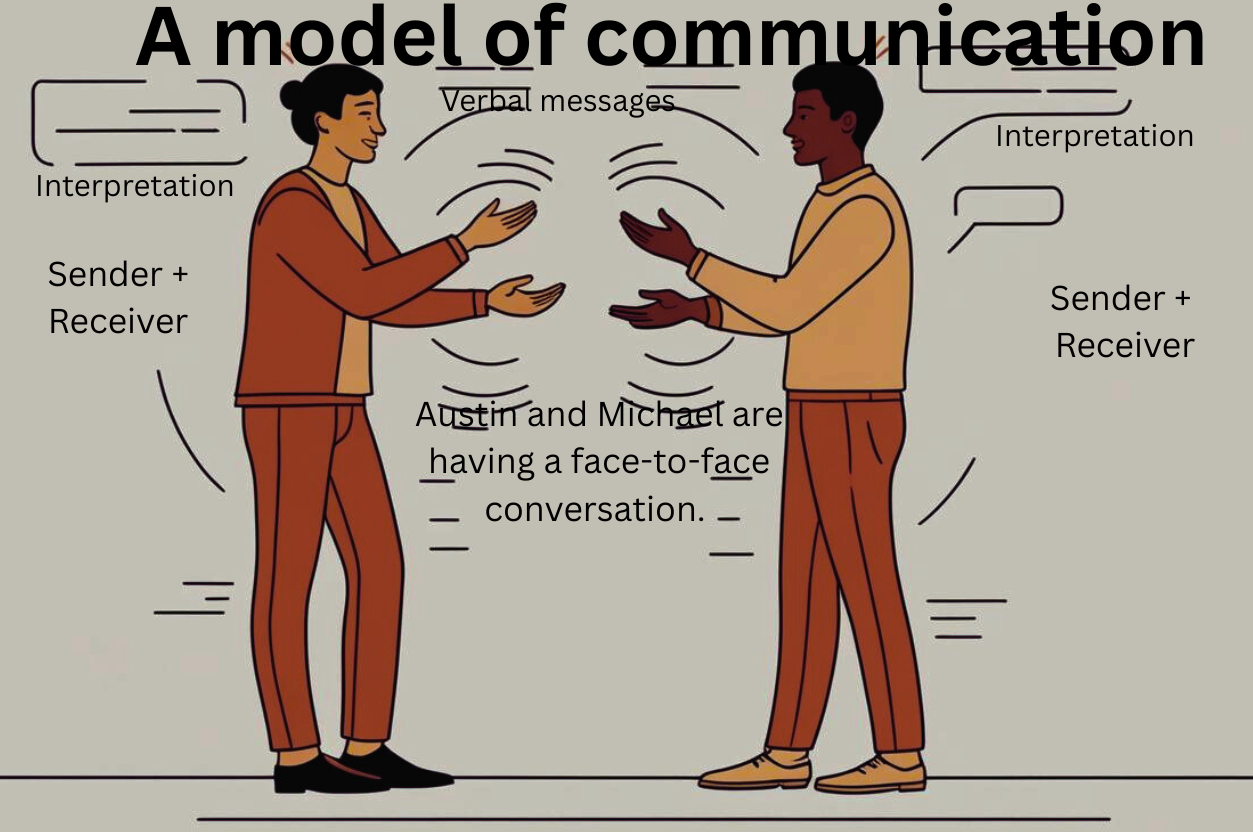

Messages are a core part of communication. They may be verbal and nonverbal. Verbal messages includes the use of words and nonverbal messages include facial expressions, eye contact, personal appearance, tone of voice, gestures, touch, posture and the use of space and time (Rothwell, 2019). The verbal and non-verbal cues are largely symbolic in nature. A symbol represents a referent or thing/object/idea, it is not the thing, object, or idea itself. How a person interprets the meaning of the symbol will depend on the individual, their culture, and their understanding of the symbol. For example, the thumbs-up gesture could have different meanings depending upon the culture. For example, in the United States, the raised thumb means “way to go” (Martin & Nakayama, 2013) whereas it is the number “one” when counting in Germany (Wolters, 2017) and is an offensive gesture in Iran (Martin & Nakayama, 2013). How many non-verbal cues are present in Figure 1.1 that shows two people facing each other while talking.

Figure 1.1

Model of Communication

Source: This image was created using AI in Canva on 03/29/2025 by Karishma Chatterjee.

In addition to verbal and non-verbal messages, communication scholars also study texts (emails, tweets, social media posts etc.), images, audio, and videos as part of the data that communicates meaning.

Communication has two levels of meaning- content and relational (Watzlawick & Beavin, 1967). Meaning represents an understanding of what is occurring when people interact. Content level is “what is said,” whereas the relational level is “how it is said.” If your friend Sam says, “Will you lend me $50.00?”, the content level is the request and the relational level is how Sam says it including the tone of voice, eye contact, and body language or the use of emojis if it is a text message. How Sam presents this “Ask” depends upon the relationship you both share, for example the length of your friendship or the closeness of your friendship. Refer to Figure 1.1, if you had to guess what type of relationship Austin and Michael have, what would you infer based on the non-verbal cues in the image?

Response is the final piece in the process of communication. A message must elicit any cognitive, behavioral or emotional reaction in the intended audience for it to be considered communication (Griffin et al.). In other words, if a person doesn’t hear you even though you asked them a question, communication hasn’t occurred. Similarly, if your friend heard you ask them a favor and felt upset or obliged and then said yes or no are all instances of communication having occurred. Finally, communication occurs via both face-to-face (in person) and mediated channels (emails, social media etc.)

One of the major mistakes amateur communicators make is the claim that they are efficient in every type of communication. This is faulty logic considering the field of communication includes variety of content that is complex in nature. For example, while a person may be highly experienced in creative writing and poetry, they may struggle with writing a one-page rejection letter to a client. Since technical writing tends to be short, strategic, and to the point, it may require a different set of skills.

While engineering majors have the training and knowledge in technical information, students are continuing to struggle with communication related concerns as they transition to the workplace (Ford et al., 2021). We have designed this text to help students learn about communication and help them develop communication speaking and writing skills.

1.2 Technical and Professional Communication

Like many technical disciplines, technical communication has an international professional organization, The Society for Technical Communication (STC.org). It characterizes technical and professional communication as either “about technical or specialized topics,” communication that “us[es] technology, such as web pages, help files, or social media sites,” or communication that “provid[es] instructions about how to do something” (STC.org, 2024). In other words, technical and professional discourses involve communicating complex information to a specific audience who will use that information to accomplish some goal or task in a manner that is accurate, useful, and clear. Based on this definition, technical and professional communication can be described as:

Purposeful

Goal oriented (in terms of both hard goals like project deadlines and soft goals like rapport-building and maintaining)

Aimed at audiences of stakeholders with agency and/or relevant credentials

Shaped by the discursive conventions of a professional community.

When you write an email to your professor or supervisor, develop a presentation or report, design a sales flyer, or create a webpage, you are engaging in technical and professional communication. Along those lines, “technical” and “professional” are used interchangeably throughout this textbook when referring to writers and/or writing produced by them. In this textbook, the word “document” refers to any of the many forms of technical writing, whether it is a web page, an instruction manual, a lab report, or a travel brochure.

1.3 Where Does Technical Communication Come From?

According to the STC, technical communication’s origins have been attributed to various eras dating back to Ancient Greece and to the Renaissance, but what we know today as the professional field of technical writing began during World War I, arising from the need for technology-based documentation for military and manufacturing industries (STC.org). As technology grew, and organizations became more global, the need and relevance for technical communication emerged, and in 2009, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics recognized Technical Writer as a profession (STC.org).

1.4 How “Technical” Writing and “Professional” Writing are Related and How they Differ

Technical communication—or technical writing—is writing about any technical topic. The term “technical” refers to specialized knowledge that is held by experts and specialists. Whatever your major is, you are developing an expertise and becoming a specialist in a particular technical area. And whenever you try to write or say anything about your field, you are engaged in technical communication.

Professional (or business) writing, on the other hand, covers much of the additional writing you’ll be doing in your profession. Professional writing includes correspondence such as emails, memos, newsletters, business letters, and cover letters, as well as other documents such as resumes, social media posts, blogs, and vlogs. While professional writing may convey technical information, it is usually briefer and targets an individual or small group of readers who may or may not be experts in the field.

1.5 Importance of Audience

Another key part of the definition of technical and professional communication is the receiver of the information—the audience. Technical communication is the delivery of technical information to readers (or listeners or viewers) in a manner that is adapted to their needs, level of understanding, and background. In fact, this audience element is so important that it is one of the cornerstones of this course: you are challenged to write about technical subjects but in a way that a beginner—a non-specialist—could understand. This ability to “translate” technical information to non-specialists is a key skill to any technical communicator. Technology companies are constantly struggling to find effective ways to help customers or potential customers understand the advantages or the operation of their new products.

In addition, communicating with employees within an organization also requires superior professional communication skills. Employees prefer detailed information in a timely manner when there are companywide changes such as layoffs and wage cuts (Sguera et al., 2021). When companies do not communicate, employees tend to become cynical and unhappy with their workplace. An individual with excellent communication skills is an asset to every organization. No matter what career you plan to pursue, learning to express yourself professionally in speech and in writing will help you get there.

Profiling or analyzing your audience takes skill and consideration. An effective communicator will need to consider the length of the message and the channel in which the message is communicated based on the audience’s needs. When you sit down to write, prepare a presentation or communicate with clients or coworkers, ask yourself the following questions:

- How big is my main audience? Is it one person, two, a few, several, a dozen, dozens, hundreds, or an indeterminately large number (the public)?

- Who might be my secondary or tertiary audiences (e.g., people you can see CC’d or people you can’t because they could be forwarded your email without you knowing)?

- What is my professional or personal relationship to them relative to their position/seniority in their organization’s hierarchy?

- How much do they already know about the topic of my message?

- What is their demographic—i.e., their age, gender, cultural background, educational level, and beliefs?

This section is adapted from the following sources:

What is Technical and Professional Communication. In Howdy or Hello? Technical and Professional Communication Copyright © 2022 by Matt McKinney, Kalani Pattison, Sarah LeMire, Kathy Anders, and Nicole Hagstrom-Schmidt, available at Howdy or Hello? Technical and Professional Communication – Simple Book Publishing licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

Analyzing Your Audience in Communication at Work (2nd ed). Copyright © 2025 by Jordan Smith, available at Communication at Work – Simple Book Publishing is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Discussion

- Discuss how verbal communication impacts your line of work.

- Discuss how written communication will be utilized in your field.

- What type of communication skills will be necessary to succeed in an engineering or science field?

- Consider audience analysis for a moment. You are writing a proposal for a land surveying company for an app to speed up their communication process related to projects. The owners of the company are from The Boomer and Gen X generation. What would be your audience considerations as you develop your proposal and upcoming presentation?

References

Ford, J. D., Paretti, M., Kotys-Schwartz, D., Howe, S., & Ott, R. (2021). New engineers’ transfer

of communication activities from school to work. IEEE Transactions on Professional

Communication, 64(2), 105–120. https://doi.org/10.1109/tpc.2021.3065854

Griffin, E., Ledbetter, A., & Sparks, G. (2015). A first look at communication theory (9th Ed.).

McGraw-Hill.

Martin, J. N. & Nakayama, T. K. (2018). Intercultural communication in contexts (7th ed.). New

York: McGraw-Hill.

Rothwell, J. D. (2019). In mixed company: Communicating in small groups and teams (10th Ed.).

Oxford University Press.

Sguera, F., Patient, D., Diehl, M., & Bobocel, R. (2021). Thank you for the bad news: Reducing

cynicism in highly identified employees during adverse organizational change. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 95(1), 90–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12369

Society for Technical Communication. Defining Technical Communication (2024). Retrieved

January 28, 2025, from https://www.stc.org/about-stc/defining-technical-communication/

Watzlawick, P., & Beavin, J. (1967). Some formal aspects of communication. The American

Behavioral Scientist 10(8); 4 – 8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764201000802

Wolters World (2017). German hand gestures that throw off tourists [Video]. YouTube.

Retrieved Jan 28, 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h8Dul0MOvc8