67 Chapter 1 What is Historical Geography?

What is Historical Geography

History is not the past but a map of the past drawn from a particular point of view to be useful to the modern traveler.[1]

Henry Glassie Passing Time in Ballymenone 1982

1.1 What is Historical Geography?

What is Historical Geography? For many, that is a good question. The Fifth Edition of The Dictionary of Human Geography defines it as “a sub-discipline of human geography concerned with the geographies of the past and with the influence of the past in shaping the geographies of the present and the future.”[2] Until the early nineteenth century, historical geography focused on the antiquarian geographies of Biblical and classical Greco-Roman history, and geography was perceived as a “stage” for history. However, as W. Gordon East, in The Geography Behind History, observes:

The familiar analogy between geography and history as the stage and the drama is in several respects misleading, for whereas a play can be acted on any stage regardless of its particular features, the course of history can never be entirely unaffected by the varieties and changes of its settings.[3]

Therefore, “history” from a geographical perspective “is not rehearsed before enactment, and so different and so changeful are its manifestations that it certainly lacks all unity of place, time and action.”[4] An example of how to think geographically about history can be found in Stephen King’s novel 11/22/63, about a time-travelling school teacher who goes back to the year 1963, to prevent the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas, Texas. King’s metaphorical use of “watersheds” and “flash floods of history” in his novel can help us think spatially about history:

“Do you know the phrase watershed moment, buddy?” . . .

“Nope.”

“Cartography. A watershed is an area of land, usually mountains or forests, that drains into a river. History is also a river . . . Sometimes the events that change history are widespread – like heavy prolonged rains over an entire watershed that can send a river out of its banks. But rivers can flood even on sunny days. All it takes is a heavy, prolonged downpour in one small area of the watershed. There are flash floods of history, too. Want some examples? How about 9/11?[5]

Furthermore, the historian Philip Ethington argues that “the past cannot exist in time: only in space. Histories representing the past represent the places (topoi) of human action. History is not an account of ‘change over time,’ as the cliché goes, but rather, change through space. Knowledge of the past, therefore, is literally cartographic: a mapping of the places of history indexed to the coordinates of spacetime.”[6] In Forward to Historical Geography (1941) Carl Ortwin Sauer, Doyen of the Berkeley School of Geography, described the work of reconstructing landscapes of the past as a “slow task of detective work.”[7] Sauer maintained that historical geographers needed the “ability to see the land with the eyes of its former occupants, from the standpoint of their needs and capacities” and cultivate “the most initimate familiarity with the terrain which the given culture occupied.”[8] He then warned:

This is about the most difficult task in all human geography, to evaluate site and situation, not from the standpoint of an educated America of to-day, but to place one’s self in the member of the cultural group and time being studied.[9]

For this reason, in North America, historical geography is a crucial and academically rigorous, sub-field of geography, but in today’s public eye, it is a somewhat marginalized field of study. This is perhaps because North America is separated from Europe, Africa and Asia by two large oceans and has been the destination for millions of people since before pre-historic times. In the last 600 years, its coasts and interiors have been explored, surveyed, and mapped, leading one to erroneously conclude that North America is a “Terra Cognita”, a “Known Land.” However, upon closer examination, landscapes of the past can appear to us in the present day—to paraphrase the geographer David Lowenthal—as “foreign countries.”[10] In summary, historical geography is a sub-field of geography that incorporates both human and physical geography and is concerned with the landscapes of the past and with the influence of the past landscapes in shaping the geographies of the present and the future. In researching and writing about the worlds of the past, a key method that historical geography has developed is the ability to situate localized research within broader, regional and global comparative contexts, and vice versa.

1.2 The Geneaology of Western Geography

In the West, the field’s origins can be traced to Herodotus’s (484-425 BCE) chronicle of events, regions and cultures, Euclid’s (300-200BCE) geometry, Eratosthenes’ (276-194 BCE) introduction of measurement and scale, Strabo’s (63 BCE-23 CE) poetic impressions of place, Ptolemy’s (100-170 CE) coordinate system, and Al-Idris’ (1100-1165 CE) cartographic calligraphy of the known world’s climatic zones.

These early geographical knowledge systems were rediscovered during the European Renaissance (1300–1600 CE) and shaped the period’s literary, historical and geographical discourse and analysis well into the European Enlightenment (1600-1900). In the seventeenth century, Philipp Clüver (1580-1622) published Germaniae antiquae libri tres (1616), an early modern historical geography on the development of Germany, based on the writings of the ancient Roman historian Tacitus (56-120 CE). However, prior to the mid-nineteenth century, historical geography tended to focus on the antiquarian geographies of Biblical and classical Greco-Roman history, the role of geography as a “stage” for history, and the geographies of discovery and historical cartography.

1.2.1 Toward Modern Historical Geography

Modern historical geography’s genealogy is protean, and the contribution of two major figures, Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) and Alexander von Humbolt (1769-1859) established a foundation for its practice which is still in place today. Kant provided the philosophical foundations for geography as an empirical, spatially focused discipline. In his Lectures on Physical Geography (published posthumously in 1802), Kant argued that geography and history together constitute the two fundamental modes of human knowledge: geography organizing phenomena in space and history organizing them in time.[11] Insisting that geography should systematically classify and compare the Earth’s various geological, climatic, biological, and cultural phenomena, Kant set the methodological basis for later geographical traditions which integrated environmental processes with human development. Kant’s distinction between Erdkunde (earth description) and physical geography laid the groundwork for subsequent debates about whether geography was a branch of the sciences, a branch of the humanities, or a discipline that synthesized both branches into its practices.[12] Humboldt’s contribution combined botany, zoology, climate, natural and cultural history with fieldwork and comparative spatial analysis establishing geography as an empirical, historically grounded discipline. Through works such as Cosmos (1845–1862), Humboldt advanced the idea that landscapes are products of long-term interactions between physical processes and human activity, thereby laying the foundation for what would become modern cultural and historical geography.[13] His comparative methods—linking climate, vegetation, colonization, and indigenous histories across continents—encouraged geographers to interpret places diachronically, not just descriptively.[14] Humboldt also promoted systematic field observations, biogeographical mapping, and analyses of human–environment relationships. Modern historical geographers continue to draw on Humboldt’s integrative approach, valuing his insistence that understanding the present requires reconstructing past historical layers of environmental and cultural change.[15]

1.3 Accidental origins: North American historical geography

In 1893, the historian Frederick J. Turner gave a talk to the American Historical Association conference meeting in Chicago, which took place during the World’s Fair. Titled The Significance of the Frontier in American History (1894), Turner’s paper, which has been described as the “classic American essay in speculative historical geography,” made the pronouncement, on the basis of his reading of the 1890 U.S. Census, that the American frontier was closed. 81 As a historian drawn to geography, Turner drafted a thesis arguing that English and European settlers’ interactions with the North American frontier uniquely shaped the United States as a nation and a democracy. Over the past one-hundred years, Turner’s “Frontier Thesis” has been lambasted by historians and geographers on one end of the academic spectrum for naïvely, conflating culture, the environment, and cartography, whereas on the other end, it has been harshly castigated by others for being a Eurocentric, racial, and gender biased promoter of environmental determinism.[16] Ironically in 1940, George W. Pierson argued that Turner had not accounted for the environmental influences of climate, crops, animals, and disease upon the course of America’s expansion.[17] Arthur M. Schlesinger Sr. flatly stated that Turner’s perspective was obsolete, because, by the 1820s, migration to cities had increased more rapidly than frontier settlements. By the 1860s, Schlesinger noted that one out of six individuals in the U.S. lived in an urban milieu containing 8,000 or more people. This led him to conclude that Turner’s “historic announcement in 1890 census was less a prophecy of an end to an old civilization, than a long overdue admission of the arrival of a new one.”[18] Murray Kane dismissed the Frontier Thesis as “dominated by anthropological and geographical determinism” and constituted “a statistical interpretation of history rather than a historical interpretation of statistics.”[19] In the 1950s, Henry Nash Smith argued that the ‘Pristine Wilderness’ myth rendering pre-Columbian North America a new “Garden of Eden” was the subtext of Turner’s thesis.[20] However, many of Turner’s students adopted his methods and revised his work. Ray Allen Billington modified Turner’s concept of the frontier as a line between ‘civilization and savagery’ to a more dynamic ‘moveable feast’ of regional settlements, resource extractions and consumption: “The frontier can be pictured meaningfully as a vast westward-moving zone, contiguous to the settled portions of settlement and peopled by a variety of individuals bent on applying individual skills to the exploitations of unusually abundant resources.”[21] Herbert Eugene Bolton, Doyen of the Spanish Borderlands School, applied aspects of Turner’s theory to study the histories of the U.S. southwest and Mexico. In contrast to the frontier, Bolton mapped out heterogeneous hispanic-indigenous regions whose populations had been largely ignored or treated one-dimensionaly by Turner’s thesis. Bolton suggested that a Western “frontier of inclusion” existed in contra-distinction to the Anglo-European-American “frontier of exclusion.”[22] Turner seems to have anticipated and encouraged the barrage of criticism aimed at his “Frontier Thesis” and refuted the charge that he was an environmental determinist. Merle Curti, one of his students, noted that Turner assumed that, in the hands of his “wiser” successors, his theoretical and speculative approaches to history and geography “would . . . be reconstructed.”[23] Richard Hofstadter, interrogated the Jeffersonian “agrarian myth” underlying Turner’s work, arguing that “the United States did not produce a distinctively rural culture,” but rather, the country’s development was based on urbanization and the extraction and exploitation of natural resources, which “unleashed in the nation an entrepreneurial zeal probably without precedent in history, a rage for business, for profits, for opportunity, for advancement.”[24] In the 1980s Annette Kolodny and Patricia Limerick noted the omission of women in Turner’s thesis, and that the American West possessed a diversity of “complicated environments occupied by natives who considered their homelands to be the center, not the edge”of a frontier.[25] Limerick did state that in Turner’s “weird hodgepodge of frontier and pioneer imagery” were “important lessons about the American identity, sense of history, and direction for the future.”[26] In contrast, Richard White argued that “Turner often placed himself and his audience not in the West but in popular representations of the West,” in order to turn the eyes of American citizens away from the memory of the Civil War and focus them “on westering as the formative experience” of the United States.[27] White also criticized Turner for “clearly” confusing “environment” with “culture.”[28] In Turner’s thesis, “frontiersmen did not accept what the environment offered; instead, they accepted what Indian cultures offered. Canoes, hunting shirts, moccasins, and war cries were not natural products of the forest. Birch trees and deer were natural to the forest. Canoes and moccasins were not. Culture, not wilderness, created them.”[29] The historian William Cronon considered “Turner’s vocabulary” and the language of his thesis more like a poet’s than that of a “logician.” Reading Turner’s 1893 essay, one can see the influences of the poet Walt Whitman, the transcendental naturalists Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, and the broad sweep of American Frontier literature found in works like James Fenimore Cooper’s 1826 novel, The Last of the Mohicans.[30] Cronon stated that Turner’s definition of the North American frontier “could mean almost anything: a line, a moving zone, a static region, a kind of society, a process of character formation, an abundance of land.” Although admitting that the “frontier thesis” was flawed, Cronon stated that nevertheless, Turner’s methods were groundbreaking. He showed how the study of North America could unfold

. . . along geographical lines that were also temporal: the frontier thesis, in effect, set American space in motion and gave it a plot . . . His stages and types had great rhetorical attractions. Seen through their lens, previously disparate phenomena and events suddenly seemed to become connected. [31]

It seems that despite the erroneous conclusions of his thesis, Turner’s innovative methods accidentally inaugurated the practice of North American historical geography: “one can easily visualize the young historian seated at a table in the library of the Wisconsin State Historical Society in 1893, poring over the latest historical atlases and census publications.”[32] In the end, Cronon concluded that “although he was uncomfortable with the shifting definitions that have plagued scholarly readings of frontier history since the days of . . . Turner,” present-day “regional redefinitions of the field are ultimately not much better.”[33] Since the publication of Turner’s essay in the United States, discussions between historians and geographers have explored how the dynamic interplay between human agency, time, and environment sculpted the landscapes of the past. Several figures helped usher in the practice of American historical geography, though their innovations were not without flaws:

- William Morris Davis (1850–1934) in The Rivers and Valleys of Pennsylvania (1889) maintained that physical landscapes were created by a long, continuous geographical cycles of erosion. As the father of geomorphology as a systematic science in the United States, Davis model was later critiqued for being teleological, overly schematic, and inconsistent with process-based geomorphology.[34]

- Ellen Churchill Semple (1863–1932) as a student of German Geographer Friedrich Ratzel whose two volume Anthropogeographie (1882-1891) examined the effects of environment on individuals and societies, introduced the idea of environmental determinism to American geography. Semple’s American History and Its Geographic Conditions (1903), which was adopted as a textbook by several colleges and Influences of Geographic Environment (1911) were influential, but later criticized for overly deterministic, ethnocentric, and reductionist interpretations.[35]

- Albert Perry Brigham (1855–1932) was an influential geography educator and author of the textbook Geographic Influences in American History (1903) which helped institutionalize geography in American schools and universities. However, his works relied on environmental determinist assumptions that were later challenged for their oversimplification and cultural biases.[36]

- Ellsworth Huntington (1876–1947) in Civilization and Climate (1915) advanced environmental determinist and climatic influence theories, linking climate cycles to civilization’s rise and fall. His work is now widely critiqued for scientific racism, climatic determinism, and speculative correlations.[37]

- Richard Hartshorne (1899–1992) who published The Nature of Geography (1939) articulated a philosophical framework for geography grounded in chorology and regional differentiation, shaping mid-twentieth-century geographical methods. Critics argued that his approach was overly descriptive, atheoretical, and resistant to quantitative, and critical turns.[38]

- Mark Jefferson (1863–1949) chief cartographer of the American Delegation to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, he published The Law of the Primate City (1939), contributing the emerging field of urban historical geography.[39] Jefferson helped formalize geographic education, notably through work with the American Geographical Society. Some critiques note that his urban models generalized from limited case studies and reflected early-twentieth-century urban developmental assumptions.[40]

1.4. The Dean of American Historical Geography

Arguably, it is Carl Ortwin Sauer who can be named as the “dean of American historical geography.”[41] After writing a Ph.D dissertation on the Ozark Highlands, Sauer developed an interest in human–environmental relations under the influence of the Germanic Landschaff (Landscape) tradition and the French Annales schools of geography and history. In a series of cultural field studies in northern Mexico, Sauer explored the roles played by time and human agency in sculpting the environments in which people lived. Sauer’s work went against the grain of early twentieth century trends in geography, by explicitly rejecting environmental determinism. In The Morphology of Landscape (1923) Sauer observed that

The cultural landscape is fashioned from a natural landscape by a cultural group. Culture is the agent, the natural area is the medium, the cultural landscape is the result. [42]

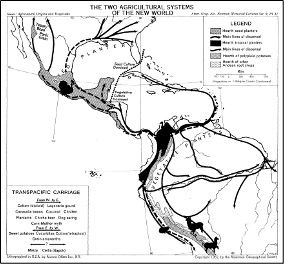

Describing geography as “a critical system which embraces the phenomenology of landscape, in order to grasp in all of its meaning and color the varied terrestrial scene,” Sauer argued that “we cannot form an idea of landscape except in terms of its time relations as well as it space relations. It is in continuous process of development, or of dissolution and replacement.”[43] Striking a balance on the interplay between cultural agency and geographical processes, Sauer invoked French Annales School founder Paul Vidal de la Blache’s warning against seeing “the earth as ‘the scene on which the activity of man unfolds itself,’ without reflecting that this scene itself is living.”[44] In Agricultural Origins and Dispersals (1952), Sauer stated that maps constituted a form of “visual hypothesis” and as intellectual tools, could help the study of relations between cultural agency, geographical processes and physical landscapes.[45]

Sauer argued that maps provided the “ideal formal geographic description”, and these visual forms of hypotheses could be “applied to an unlimited number of phenomena. Thus, there is a geography of every disease, of dialects and idioms, of bank failures, perhaps of genius.” [46] In 1953, Sauer helped organize a symposium Man’s role in changing the face of the earth during which he made one of the most definitive statement on the aims of historical geography in studying not only North America, but the planet’s other major continents as well:

It is concerned with historically cumulative effects, with the physical and biological processes that man sets in motion, inhibits, or deflects, and with differences in cultural conduct that distinguish one human group from another.[47]

Sauer’s work emphasized cultural landscapes, fieldwork, and historical spatial patterns and interpretations, and had a considerable influence on the development and traditions of American historical geography.[48] Despite Sauer’s impact, his work has been more recently critiqued as being anti-theoretical, nostalgic, and insufficiently attentive to the issues of power, economy, and modernity that became the concern of the “New Cultural Geography” of the 1980s and ‘90s.[49] In the late twentieth century, “cultural and spatial turns” in the humanities and social sciences shifted historical geography’s focus to post-colonialism, the crisis of representation and postmodernism. A critique of orthodox methods called for engagements with cultural, Marxist, gender, ethnic and feminist theories rather than relying solely on empirical descriptions of historical regions. Historical geography subsequently synthesized traditional methods, with structuralist, hermeneutic, philosophical, linguistical, feminist and post-colonial perspectives.[50] In addition, in the past decade, historical geographers have started working with geographical information systems (GIS) to flesh out studies of past landscapes and regions via visual and spatial analyses. [51]

1.5 Book Contents

Perceptions of North America’s cultures and landscapes have evolved over its long history, offering no definitive perspectives but rather a montage of entangled stories and surveys of the continent’s diverse regions, periods, cultures and senses of place. This section provides a précis on the chapters to help readers orient themselves to the structure and content of this textbook. Chapter 2: Physical Geography of North America provides a regional overview of the physiography of the third largest continent on Earth. Extending south from the Isthmus of Panama to Alaska, the Aleutian Islands and Arctic regions in the north, the countries of Canada, the United States, and Mexico occupy most of the continent’s landmass sharing the descending western mountain spine of the North American Cordillera. This chapter discusses the continent’s physical geography and regional landscapes, its watersheds and hydrography, and its climate and weather. In Chapter 3: Geographical Imaginations and Cartographic Inventions of North America, we find that the sixteenth-century Spanish, French and British cartographical perspectives of North America were very different from the indigenous perceptions of the Olmecs, Aztecs and Mayans, who inhabited present-day Mexico, and the native nations that occupy the present-day United States and Canada. For example, the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee –People of the Longhouse) Confederacy’s conception of North America as “Turtle Island” imparted a continental cosmography was shared by other native nations. In the late nineteenth century, the Ghost Dance emerged as an embodied mapping of sacred space that was performed by the Great Plains and Southwestern nations in resistance to the expansion of the United States.Several theories are discussed in Chapter 4: Pre-Columbian North America, from the Upper Paleolithic to 1492, to explain how the continent was settled in the pre-Columbian period. Humans are a migratory species and this complex phenomenon is the focus of many archaeological, genetic, and paleoenvironmental studies. Pollen samples, deep sea and ice cores, radio carbon D.N.A. dating of human remains and artifacts such as those discovered at Chiquihhite Cave in Mexico, have provided scientists and archaeologists with increasing evidence that North America settled 30,000 years ago, before the last ice age. Long before the official European first contact in 1492, native nations in North America maintained their own complex networks of exchange, diplomacy, colonialism and conflict—trading across vast distances, forming alliances, waging wars for economic and territorial gain, and taking and owning slaves. Chapter 5: Post-Columbian Indigenous North America discusses how many of these practices continued after European contact, illustrating that native nations were active agents in shaping modern North American continental history rather than just being passive and “vanishing” cultures impacted by European colonial incursions. The Columbian Exchange in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries altered not only the biogeography, but also patterns of settlement, labor, and power across the emerging Transatlantic world.[52] Chap 6: 1492-1800: Migrations, Frontiers, Homelands and Wars explores this newly connected Atlantic world and how the geographic foundations of the Spanish, French, and British colonial expansions in North America were established. The Spanish were the first to consolidate imperial networks across the Caribbean, Southwestern and South American interiors, driven by the extraction of silver and gold and the establishment of Catholic missions and military presidios. The French and British followed, competing for access to trade, land, and indigenous alliances in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Each empire adapted the ecological legacies of the Columbian Exchange to its own colonial geography: the Spanish introduced cattle ranching and mission agriculture to the Southwest; the French integrated fur-trading economies into existing indigenous ecologies across riverine networks of the St. Lawrence, Great Lakes and Ohio and Mississippi valley regions; and the British established agricultural colonies from New England down the eastern seaboard that were dependent on mercantile transatlantic trade and exchanges of enslaved Africans, tobacco, sugar, and rice. The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 doubled the size of the United States, setting the stage for the nation’s westward expansion, which politically and culturally transformed the North American continent in the early to mid-nineteenth century. The major regional developments during this period discussed in Chapter 7: Continental Expansions 1800-1850 include the dissolution of New Spain and Mexican independence, the establishment of the United States-Canada border, the Texas revolution and annexation, the Mexican-American War and the U.S. Civil War. The political and economic development of the North American continent in the latter half of the nineteenth and early parts of the twentieth century was shaped by the dynamic interplay of several geographical processes: the shift in transportation infrastructure from rivers and roads to railroads; the shift from wind, water and animal power to energy sources through the extraction of coal and oil; and the role of ore and iron in the industrialization and urbanization of the continent. Chapter 8: Transcontinental North America 1850-1915 discusses how transport systems, resource extractions and manufacturing integrated at a continental scale to radically shape North American landscapes from 1850 to the early decades of the twentieth century. Finally, Chapter 9, Global North America, 1915-2000, discusses how the rise of North American globalization in the late twentieth and early twentieth centuries unfolded in three distinct, although overlapping political-economic geographies known as the Mercantile, Industrial and Globalized Services and Hi-Tech eras. Each era was characterized by a specific dominant political‒economic logic and a corresponding system of resource extraction, commerce, industry, transport, and communication technologies that shaped the spatial growth and distribution of North America’s cities, rural areas and regions. This macro historical-geographical perspective affords us a view of North America not as a static, continental map but as a number of dynamic and intersecting landscapes that are continually being reshaped by resource extractions and political, economic and cultural forces, which intersect and interact on a global scale with other world regional geographies in Europe, Africa and Asia.

1.6 Conclusion: North American Regions and Historical Geography Dating Styles

When geographers study continents, they use the concept of a region as a tool for organizing and simplifying the vast complexity of the surface of the Earth into intelligible, meaningful and manageable units. Regions are areas with one or more shared characteristics, and their boundaries are defined on the basis of the specific traits being studied and mapped by geographers. These characteristics can be physical, such as climate, or human-based, such as culture. Generally, geographers categorize regions according to three conceptual scales:

- the formal region (an area that shares a common physical or human trait);

- the functional region (how an area operates within a physical or human network); and

- the vernacular region (a subjective scale based upon people’s perceptions of landscape, cultural identity, and sense of place, which creates the ‘personality’ of a region).

A single location in North America can often belong to multiple, overlapping formal, functional and vernacular landscapes and regions simultaneously. For example, Arlington, Texas, sits at the intersection of the tail of the Appalachian Range, the edge of the Deep South, and the gateway to the Great Plains and American Southwest. Culturally, it is a mosaic of Anglo-European, Hispanic, African-American, Asian and indigenous cultures. The Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex also operates as a node on a global network connected by air travel and digital telecommunications, and Arlingon itself is the home of the Dallas Cowboys and Texas Rangers, two major football and baseball franchises that are members of national sports leagues and regional divisions.

1.6.1 Nota Bene (Note Well) Historical Geography Dating Systems

In the Landscape of History (2002), John Lewis Gaddis asks, “What if we were to think of history as a kind of mapping?” Gaddis links the ancient practice of mapmaking within the archetypal triptych of perceived and anticpated time (past, present, and future) and states that cartography and narrative are both techniques to manage infinitely complex subjects by imposing abstract grids and concepts, such as longitude and latitude to frame locations, or hours and days to denote time. The foundations of historical chronology are shaped in part by the transition from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar. Established by Julius Caesar in 46 BCE, the Julian calendar miscalculated the solar year by approximately eleven minutes, resulting in a cumulative drift of approximately ten days by the sixteenth century. To correct this discrepancy, Pope Gregory XIII introduced the Gregorian calendar in 1582, which revised leap-year rules and realigned the calendar with the equinox. Catholic countries adopted the new system immediately, whereas others converted gradually over the following centuries—Britain and its colonies not until 1752 and Russia after the 1917 revolution—leading to significant dating inconsistencies across historical documents.[53] Historical geographers utilize chorology (the map as a visual hypothesis) and, depending on the period of their studies, the chronologies of the Julian or Gregorian calendars.[54] Within the Gregorian calendar system, scholars have come to distinguish between major year-labeling styles. The traditional BC (Before Christ) and AD (Anno Domini) notation centers dates around the estimated birth year of Jesus, marking years before and after this point.[55] The secular equivalents, BCE (Before Common Era) and CE (Common Era), use identical numerical values but explicitly avoid Christian terminology. A third system, common in archaeology and the earth and environmental sciences, is BP (Before Present), which measures time backward from a fixed reference year of 1950 CE, selected because radiocarbon dating became widespread at that time. Thus, 10,000 BP corresponds to approximately 8,050 BCE. This textbook utilizes the second (BCE/CE) and third systems (BP).[56]

Sources and notes

[1] Glassie, H. 1982. Passing Time in Ballymenone: Culture and History of an Ulster Community. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pg. 621.

[2] Gregory, D., Johnston, R., Pratt, G., Watts, M., Whatmore, S. 2009. The Dictionary Human Geography, 5th Ed. London: Wiley-Blackwell. Ref. 332.

[3] East, W.G. 1965. The Geography Behind History. New York: Norton & Company, Inc., pg. 2

[4] Ibid.

[5] King, S. 2011. 11/22/63. N.Y.: Scribner, pg. 57.

[6] Ethington, P. J. 2007. Placing the past: ‘Groundwork’ for a spatial theory of history. Rethinking History, 11(4), 465–493. Ref.

[7] Sauer, C.O., 1941. Foreword to historical geography. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 31(1), pp.1-24.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Lowenthal, D., 1975. Past time, present place: landscape and memory. Geographical review, pp.1-36.

[11] May, J. A. 1970. Kant’s Concept of Geography and its Relation to Recent Geographical Thought. University of Toronto Press.

[12] Livingstone, D.N. 1992. The Geographical Tradition. Oxford: Blackwell.

[13] Ibid.

[14] To study a phenomenon diachronically is to study it as it changes and develops over a period of time. As a method it focuses on historical progression or decline and/or evolution or regression, as opposed to looking at a phenomena at a single point in time.

[15]Wulf, A. 2015. The Invention of Nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s New World. New York: Knopf.

[16] Environmental determinism is the theory that the physical environment, including climate and geography, shapes and determines human culture and societal development. It suggests that factors like climate influence human traits, social behaviors, and economic outcomes. This theory is largely considered outdated and has been criticized for being overly simplistic, leading to alternative theories like possibilism, which states that the environment sets limitations but humans have the agency to choose how to respond to those limitations.

[17] Gressley, G.M. 1958. The Turner Thesis: A Problem in Historiography, Agricultural History 32, no. 4: 237.

[18] Ibid., 236.

[19] Ibid., 236-237.

[20] Smith, H.N., 1978. Virgin Land: The American West as Symbol and Myth. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.; Popper, D.E., Lang, R.E., and Popper, F.J. 2009. From Maps to Myth: The Census, Turner, and the Idea of the Frontier, The Journal of American Culture 23, no. 1: 92; Simonson, H.P. 1964. Frederick Jackson Turner: Frontier History as Art, The Antioch Review, 24, no. 2: 202-203.

[21] Ray Billington referenced in, (Ed.) Wunder, J. 1988. Historians of the American Frontier: A Bio-Bibliographic Sourcebook. New York: Greenwood Press: 100.

[22] Weber, D.J., 1986. Turner, the Boltonians, and the Borderlands, The American Historical Review 91, no. 1: 67; Mikesell, M.W. 1960. “Comparative Studies in Frontier History,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 50: 65.

[23] Gressley, The Turner Thesis, 240.

[24] Ibid., 239.

[25] Kolodny, A. 1984. The Land Before Her: Fantasy and Experience of the American Frontiers, 1630-1860. Chapel Hill: UNC Press Books; Limerick, P.N. 1987. Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West. New York: 26.

[26] Limerick, P.N. 2001. The Adventures of the Frontier in the Twentieth Century,” in Ed. Brad Gambill, et al., The Great Plains: Writing Across the Disciplines, ed. Brad Gambill, et al., Fort Worth: Harcourt: 94.

[27] White, R. 2017. The Republic for which it stands: The United States During Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865-1896, New York: Oxford University Press: 763.

[28] Richard White, referenced in Wunder, J. 1988. Historians of the American Frontier: A Bio-Bibliographical Source Book. London: Bloomsbury: 665.

[29] Wunder, J. 1988. Historians of the American Frontier: A Bio-Bibliographical Source Book. London: Bloomsbury.

[30] Travis, C., 2023. Reterritorializing Frederick Jackson Turner’s Rhetorical Cartography: Reconsidering the US Census 1870–1900 and the Multiple and Intersecting Landscapes of the American Frontier. Historical Geography, 51(1), pp.25-61.

[31] Cronon, W. 1987. “Revisiting the Vanishing Frontier: The Legacy of Frederick Jackson Turner,” Western Historical Quarterly, 18, no. 2: 166.

[32] Block, R.H. 1980. Frederick Jackson Turner and American Geography. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 70, no. 1: 34.

[33] Cronon, W. 1991. Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West. New York: WW. Norton: xvi.

[34] Davis, W.M. 1899. The geographical cycle, Geographical Journal, 14(5): 481–504.; Chorley, R.J., Schumm, S.A. and Sugden, D.E. 1964. Geomorphology. London: Methuen.

[35] Semple, E.C. 1911. Influences of Geographic Environment: On the Basis of Ratzel’s System of Anthropo-Geography. New York: Henry Holt; Livingstone, D.N. 1992. The Geographical Tradition: Episodes in the History of a Contested Enterprise. Oxford: Blackwell.

[36] Brigham, A.P. 1903. Geographic Influences in American History. New York: Ginn & Company.

[37] Huntington, E. 1907. The Pulse of Asia: A Journey in Central Asia, Illustrating the Geographic Basis of History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.; Peet, R. 1985. The social origins of environmental determinism, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 75(3): 309–333.

[38] Hartshorne, R. 1939. The Nature of Geography: A Critical Survey of Current Thought in the Light of the Past. Lancaster, PA: Association of American Geographers.; Schaefer, F.K. 1953. Exceptionalism in geography: A methodological examination’, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 43(3): 226–249.

[39] Jefferson, Mark. 1939. The Law of the Primate City. Geographical Review. 29 (29): 226–232.

[40] Jefferson, M. 1939. The law of the primate city, Geographical Review, 29(2): 226–232.

[41] Boyer, C.R. 2011. Geographic Regionalism and Natural Diversity in A Companion to Mexican History and Culture, ed. William H. Beezley. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell: 126.

[42] Sauer, C. O. 1969. Land and life. University of California Press.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Thomas, W.L., 1956. Man’s Role in Changing the Face of the Earth. Chicago, University of Chicago Press. Ref 49.

[48] Notable works in American historical geography that bear Sauer’s influence include: E. Cotton Mather’s The American Great Plains (1972) parsed this ‘inarticulated’ region of the ‘West’ physiographically and culturally, while down in cotton and bible belt of the U.S.A., Sam Bowers Hilliard’s Hogmeat and Hoecake: Food Supply in the Old South, 1840-1860 (1972) adopted computing techniques to explore county level census records. Hilliard’s study of subsistence staples, blended demographic techniques and research into the environmental conditions such as precipitation and temperature which played a role in the production and diffusion of such staples. Carville V. Earle’s, The Evolution of a Tidewater Settlement System: All Hallow’s Parish, Maryland, 1670-1783 (1975) studied a small, niche on the Atlantic seaboard at a local scale to explore the dynamic impacts of colonial settlement. Earle’s work revisited assumptions on how the tobacco economy impacted the soils and affected the physical landscape of the parish. In Geographical inquiry and American historical problems, (1992) Earle teased out his distinction between historical geography and geographical history. The former “focuses upon those relationships which have shaped the evolution of place and landscape,”[48] while the latter focuses upon those relationships which have shaped human affairs in the past.” [48] This distinction, rested on Earle’s “personal embrace of the locational and ecological (environmental) traditions within geography.”[48] Terry G. Jordan-Bychkov and Matti Kaups’ The American Backwoods Frontier: An Ethical and Ecological Interpretation (1989) debunked the cliché of Scots-Irish pioneer ‘Manifest Destiny’ dominance by applying methods of cultural ecology’ to argue that “American backwoods culture had significant northern European roots,”[48] as a result of the “interplay between the unique history of a culture and its physical environment.”[48] William Cronin’s Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (1991) mapped out the American history of the nineteenth century from the environmental perspective of the quintessential American city sitting on the shore of Lake Michigan. In a collection of eleven essays, The desert is no lady: Southwestern landscapes in women’s writing and art (1997) edited by Vera Norwood and Janice Monk, consider what landscape means to Anglo, Hispanic, Mexican-American, and Indigenous women. The essays form a mosaic of perceptions drawn from genres stretching from poetry to photography, transposed upon and emanating from the physical geography of the region. A masterwork in the historical geography of the continent is D.W. Meinig’s The Shaping of America: A Geographical Perspective on 500 Years of History (1986, 1993, 1998, 2004) stands as a monumental work of North America historical geography, harking back to the tradition of a Braudelian grand project. Meing’s panoramic, four volume study mapped out the regional stages of settlement, national development and postcolonial creation of vernacular landscapes in the United States from 1492 to 2000. [48] Craig E. Colton’s An Unnatural Metropolis Wresting New Orleans from Nature (2006) illustrates how between 1800 and 2000 the Big Easy’s cityscape was altered by engineering the floodplain of the Mississippi delta with ramifications for a variety of issues concerning cultural, ethnic, and environmental justice in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. David Wishart’s The Last Days of the Rainbelt (2013) provides a geo-historiography on how the amount of precipitation in parts of Nebraska, Colorado and Kansas was exaggerated and manipulated by private and public interests to promote nineteenth century pioneer settlement. In reality, despite well-digging and irrigation to draw water from the colossal Ogallala Aquifer, this region of the High Plains was less agriculturally productive than advertised or in practice. Last, Graeme Wynn’s The landscape of Canadian Environmental History: Empires of nature and the nature of empires (2014) draws on British and North American practices in historical geography, establishing a common ground to address human induced global climate change, which without argument, is the most significant challenge to our shared human condition.

[49] Mitchell, D. 2000. Cultural Geography: A Critical Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell.

[50] In particular, Allan Pred’s Lost words and lost worlds: Modernity and the language of everyday life in late nineteenth century Stockholm (1990) symbolize a theoretical and methodological apogee in historical geography’s response to the quantitative revolution. Employing time-geographic montage, historical and linguistic methods, the work mapped the daily life path of a Swedish docker named Sörmlands-Nisse. Other Notable works in recent historical geography include Derek Gregory’s Regional Transformation and Industrial Revolution: A Geography of the Yorkshire Woollen Industry (1982), Denis Cosgrove and Stephen Daniels, The iconography of landscape: essays on symbolic landscapes of the past (1988), J. B. Harley’s Deconstructing the Map (1989) Alison Blunt, Travel, Gender and Imperialism: Mary Kingsley and West Africa (1994), Miles Ogborn, Space of Modernity: London’s Geographies, 1680-1780 (1998) Stuart Elden’s Mapping the present: Heidegger, Foucault and the project of a spatial history (2001) and William J. Smyth, Map-Making, Landscapes and Memory: A geography of Colonial and Early Modern Ireland c. illustrated engagements with structuralist, hermeneutic, philosophical, linguistical feminist and postcolonial thought. In Travels with Feminist Historical Geography (2003) Mona Domosh and Karen Morin state that historical geography is already feminist and understating geographical change through time is important for understanding relationships between gender, space, place, and environment. Jared Diamond’s Pulitzer-Prize winning Guns, Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies (1997) drew on tropes in Anglo-American historical geography, and met with a backlash from social scientists, historical, human and critical geographers who argued that the book reintroduced environmental determinism into the public imagination. Diamond responded by making distinctions between late nineteenth century racialized discourses, and his own consideration of geographical factors and human agency. He argued that that climate and environment do affect lifestyle choices by pointing out that Inuits living north of the Arctic Circle created warm fur clothing, but not farming practices, in comparison to cultures in equatorial Papua New Guinea who had no need for warm clothing but were able to developed agriculture.

[51] See: Travis, C., 2015. Visual geo-literary and historical analysis, tweetflickrtubing, and James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922). Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 105(5), pp. 927-950. Geographical information systems (GIS) was developed by the Canada Land Inventory in the early 1960s, and took flight with Ian McHarg’s Design With Nature (1969). Between the 1960s and 1980s geocomputing labs at the University of Edinburgh, and Harvard University developed mainstream GIS platforms for academic, public and private use Initially, GIS was adopted by the earth and environmental studies and urban planning, but in the 1990s and 2000s GIS was employed in historical geography research and by historians. Such projects included the Great Britain Historical GIS at Portsmouth University in the U.K., and the China Historical GIS at Harvard University and more recently at the Spatial History Project at Stanford University. Although many historians, geographers and geoscientists regard geographical information science (GIS), as a mapping practice, its platforms have evolved into new types of visual database technology, and interactive media. As a database technology, GIS spatially parses and itemizes attribute data (as a row of statistics, a string of text, an image, a movie) linking coordinates to representations of the locations to which the data refers. As a form of media, GIS holds the possibility to “transcend the instrumental rationality currently rampant among both GIS developers and GIS practitioners and cultivate a more holistic approach to the nonlinear relationships between GIS and society.” With the advent of the digital and coding revolutions “the idea of nature is becoming very hard to separate from the digital tools and media we use to observe, interpret, and manage it.” Indeed “until recently, place has been off the intellectual radar screen of GIScientists, many of whom appear to use the two terms place and space somewhat interchangeably.” In this light, historical geography and textual analysis methods can help address “the underlying complexities in the human organization of space that present methodological problems for GIS in linking empirical research questions with alternative theoretical frameworks.” Key texts in Historical GIS include Anne Kelly Knowles’ Past Time, Past Place: GIS for history (2002), Ian Gregory and Paul Ell’s, Historical GIS: Techniques, methodologies and scholarship (2003), Meghan Cope and Sara Elwood’s, Qualitative GIS: A Mixed Methods Approach (2009), David Bodenhamer, John Corrigan and Trevor M. Harris’ The Spatial Humanities: GIS and the future of humanities scholarship (2010), Alexander von Lunen and Charles Travis’ History and GIS: Epistemologies, Considerations, Reflections (2012), and last, Charles Travis’s Abstract Machine: Humanities GIS (2015) surveyed periods of Irish literary, social and cultural history sourcing archival and cartographical documents.

[52] Cook, N. D. 1998. Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492–1650. Cambridge University Press.

[53] Richards, E. G. 1988. Mapping Time: The Calendar and Its History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[54] Chorology: From the Greek χῶρος, khōros, “place, space.” The study of relations, distributions, and patterns of phenomena over various geographical scales. Chronology: From the Latin chronologia, and Greek χρόνος, chrónos, “time” and -λογία, –logia. Thepractice and science of arranging events, periods, ages, scales in temporal sequence or occurrence in time.

[55] Greenway, D.E., 1999. Dates in history: chronology and memory. Historical Research, 72(178), pp.127-139.

[56] Mark, J. J. (2017, March 27). World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved from <https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1041/the-origin–history-of-the-bcece-dating-system/>

Media Attributions

- Fig. 1 Al-Idrisi

- Fig. 2 Agricultural dispersals © Carl O. Sauer