Chapter 9: Sustainable Freight

Chapter Overview

In this chapter, we discuss the policies and strategies used to ensure sustainability in the freight movement process. Everything from retail to services, construction to waste collection rely on an efficient and reliable freight transport system. However, with the increasing pressures of urbanization, this has to be balanced with the environmental and social impacts caused by transport activity. This is the challenge of City Logistics, a field of study that has significant practical implications for the world and the cities we live in. It is not merely a question of what is involved, but what can be done about urban freight transport to improve it for the sake of economic efficiency, quality of life, and sustainability. This chapter will give you the tools you need to understand the complexities of urban freight transport systems.

Chapter Topics

- Sustainable Urban Freight Transport

- Urban Freight as a System

- City Logistics Solutions

- Evaluation of City Logistics

Learning Objectives

At the end of the chapter, the reader should be able to do the following:

- Understand the complex nature of urban freight transport systems.

- Evaluate freight traffic impact.s

- Explore the different approaches to solving urban freight transport problems.

- Identify the research methods used to develop and apply knowledge in this field.

- Identify the main logistics challenges facing cities around the world.

Sustainable Urban Freight Transport

Building on the definition of sustainability, we can consider a transport system to be sustainable if it contributes to overall economic growth as well as social equity, without degrading the natural environment. There are several trends that point to a strong growth of urban freight transport around the world, such as the general growth of the economy and the steep growth of e-commerce. The problem is that urban freight activity in many instances lead to direct impacts on the environment, society and economy. Some impacts, of course, are more severe and urgent than others. The impacts, such as air and noise pollution, traffic accidents, congestion and the emissions of greenhouse gases, lead to unsustainable outcomes, such as climate change, poor health and safety outcomes, delays and, eventually, unlivable cities.

We can often get the impression that freight activity are only “bad”, but that is not the case. The freight system holds, first and foremost, a functional role, which is to facilitate the movement of freight, a function essential to the economy and living of the urban residents. Hence, any solution aimed at reducing the negative impacts of urban freight should take care that the service quality of the freight system is not too diminished either.

So, a balanced view will at least have four aspects considered:

- Logistics service quality

- General condition of the transport system

- Environmental concerns and impacts

- Social concerns

Logistics service quality

Goods delivery and pick-up can be regarded at the micro-, meso- and macro-economic level. The micro level is that of the individual firms. Shops sell their goods and order fresh produce, and city logistics operators deliver them at the required location. Accessibility, average speed, reliability and delivery costs are important here. By keeping logistic costs down, goods stay attractive for buyers. This has a positive impact on the productivity of entire sectors of the city’s economy, including construction, retail and tourism (meso level impact). This increases the volume and diversity of the goods and services available and increases the return of investments in the city, which in turn contributes to economic development (macro level impact).

General condition of the transport system

With a growing number of people living in cities, both passenger and freight transport will grow substantially. The city’s government may spend part of the tax income on infrastructure in order to keep the economy on its growth path. However, if these investments cannot keep up with the growth in traffic, congestion can become worse. This makes it more difficult to deliver goods on time and at low costs. Congestion also leads to an increase of traffic emissions (e.g. carbon monoxide). A negative cycle may start. Economic development may slow down. Companies and people may migrate away to less congested areas, creating new flows every time they want to return to the city, thereby increasing congestion. Although bad city logistics cannot be blamed for all these transport problems, it can be part of the problem – and the solution.

Environmental concerns and impacts

City logistics takes place with motorized and non-motorized vehicles and equipment. In most cases roads are used to transport the goods, but there are also examples where inland waterways and railways are used to ship goods in and out of cities. A growing use of motorized transport vehicles leads to a growing use of fossil fuels. This has many negative environmental impacts. One of these is the depletion of natural resources. The emission of carbon dioxide contributes to climate change. Mining and production of conventional vehicle fuels damages and pollutes the environment as well. Air pollution (such as nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide, particulate matter and sulfur dioxides) is also a well-known side effect of the combustion of fuels in engines. Particles as small or smaller than 10 micrometers (also known as PM10) result from the wear of tires and brakes. There are also other environmental effects, for instance a visual pollution or intrusion in the landscape, roads acting as physical barriers for pedestrians, or loss of green areas. Contamination of land with toxic or other hazardous materials may occur during production, maintenance and use of vehicles (e.g., loss of fluids, wear of brake pads). It may also occur during construction, maintenance and use (e.g. run-offs) of infrastructure. Finally, there is waste produced during the lifecycle of vehicles and infrastructure.

Social concerns

The urban freight sector has an important social impact as well, both positive and negative. A positive impact is that city logistics provides many jobs, either directly or indirectly. Having a job means a higher standard of living and more diverse spending opportunities (on education etc.). Another positive impact is that efficient city logistics allows people to consume a wider range of goods. The negative social impacts of city logistics may relate to environmental effects. Air pollution, noise and safety hazards may make the city a less pleasant, less safe and it affects health. Inhalation of smoke is linked to respiratory diseases. Traffic safety, especially of vulnerable road users like cyclists and pedestrians, are difficult problems facing many cities around the world, causing unnecessarily high fatalities. One should also note that these effects are not equally distributed to members of society, but affect usually poorer areas.

Urban Freight as a System

The domain of urban freight transport has many facets and touches our lives in different ways sometimes. So, it is important to first define the terms and concepts that will be used throughout the rest of this chapter. This will help us to be clear about what we mean when we use a specific term, and help us communicate with one another better. The next video will introduce some of these terms and fundamental concepts.

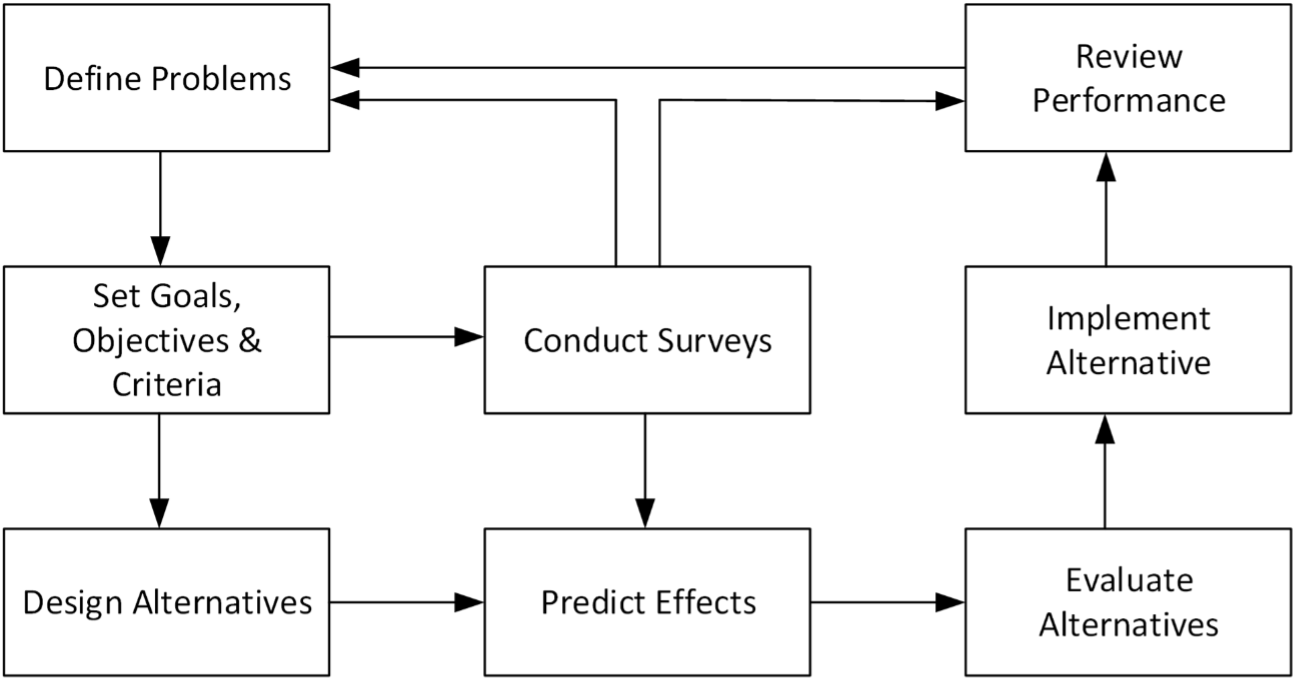

A systems approach to urban distribution is an integrated process aimed at improving performance of urban distribution systems, that involves a number of activities, including defining problems, conducting surveys, setting goals, objectives and criteria, designing alternatives, predicting and evaluating the performance of alternatives, implementing an alternative and reviewing the performance of the system (Figure 9.1).

City Logistics Solutions

In this chapter, we will briefly describe some of the city logistics schemes that have been studied and implemented. We will not be able to cover them all, since they are truly many (see Table 9.1). The main focus will be interesting perspectives that practitioners and researchers have in solving some of the challenges of urban freight transport.

| Main category | Approach | Specific action | Private sector reaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Private/Public infrastructure |

Transfer points | City terminals | Incorporate spaces into logistics chain; consolidate deliveries/collection; shift to smaller & cleaner road vehicles or other modes. |

| Outskirts logistic centers | |||

| Logistic improvement of terminals | |||

| Use of rail or ship terminals | |||

| Use of public parking lots | |||

| Modal shift | Use of the train or underground system | ||

| Shuttle train | |||

| Land use

management |

Parking | (smart) Load zone provision | Avoid on-street parking for loading and unloading activities; less congestion; higher reliability. |

| Parking space planning | |||

| Hub areas | |||

| Use of other reserved spaces | |||

| Building regulations | Load/unload interfaces | ||

| Use of private parking lots | |||

| Mini-warehouse | Consolidate delivery to only one location (per block/small walkable area) |

||

| Access conditions |

Spatial restrictions | Access according to weight, volume, width, height & length |

Shift to smaller vehicles (but also MORE vehicles) |

| Access to pedestrian zones | Shift to small/clean vehicles | ||

| Street blocking allowance | Minimize impact of delivery activity/increase safety |

||

| Closing the center to private traffic | Access given to freight vehicles during a time-window |

||

| Environmental zoning restricting polluting vehicles or zero-emission zones |

Reduction of emissions | ||

| Road pricing | Overall reduction in unnecessary traffic |

||

| Time restrictions | Adequate rotation in load zones | Increase utilization of load zones | |

| Night deliveries | Shift to off-hour delivery | ||

| Double-parking short time restrictions | Minimize impact of delivery activity | ||

| Access time windows | Avoid congested periods or pedestrian/shopping hours |

||

| Traffic

management |

Scope of regulations | Carrier classification | Apply for appropriate classification, with best traffic permissions |

| Freight zone classification | – | ||

| Harmonization of regulations | – | ||

| Street classification | – | ||

| Information | On-line load zone reservations | Dynamic routing |

Access Restrictions

Time Access Restrictions

Time access restrictions, also known as time-windows, restrict trucks from entering a certain area within a certain time. The time-window area is often the city center or even a smaller part, the pedestrian area within the city center. Sometimes time-window restrictions allow delivery trucks access for a certain time period to areas where normally no motorized vehicles are allowed, such as pedestrian areas.

Vehicle Restrictions

Vehicle restrictions prevent vehicles that have certain characteristics from entering a certain area (e.g., city center, specific streets). Vehicle restrictions can apply to various vehicle characteristics, such as length, width, height, axle pressure, and weight. A specific vehicle restriction, the amount of emissions emitted by the vehicle’s engine, is discussed in another restriction, the low emission zone.

Low Emission Zones/Environmental Zones (Engine Restrictions)

Low emission zones or environmental zones restrict polluting vehicles from entering a defined area. This can be considered an advanced type of vehicle restrictions. Usually the vehicle receives a special sticker that marks it as qualified to enter the zone.

Vehicle Load Factor Controls

A vehicle’s load factor should ensure that only fully (or at least to a certain extent) loaded vehicles enter an area, such as the city center. Urban freight vehicles have, on average, a low load factor (due to several reasons). Enforcement of such controls are difficult.

Road Pricing

Road pricing is an access regulation that usually affects not only freight transport, but all transport, although the prices might discriminate between passenger and freight transportation. Depending on the primary function of the road pricing, the price may increase for different times in a day or depending on how “clean” the vehicle is. Note that this not a restriction per se, but falls more under traffic management schemes.

Parking and Unloading Restrictions

Finally, parking and unloading restrictions regulate the locations in an area where large vehicles are allowed to park in order to unload deliveries or load pickups. Parking restrictions on other road users might also be used to facilitate the loading and unloading activities of freight vehicles on a particular street at a particular time.

Vehicle Technology

A key aspect of the transport system is the vehicle! A vehicle can be understood in a broader sense than just a machine running on the road carrying your freight. It also extends to non-mechanical means, like walking, or to continuous distribution systems, like pipelines. In this video, we will focus on the most common considerations for deciding between vehicle types from the point of view of freight carriers.

Consolidation and Transshipment of Freight

The subject of consolidation and transshipment is a regular topic in logistics management, because of the possibility to increase the utilization and efficiency of resources. Ron introduces the topic of urban consolidation centers and the main advantages and disadvantages to the solution in the video below.

Shared Logistics

An important approach to deal with inefficiencies in the urban freight system is for companies to cooperate more with each other. Here, we restrict the discussion to horizontal logistics cooperation, rather than vertical logistics cooperation (such as integration along the supply chain or sub-contracting).

In urban freight, we can identify three types of objects shared among cooperating companies:

- Order sharing

- Capacity sharing

- Information sharing.

In order sharing, “collaborating carriers combine, share or exchange customers orders or requests” for the purpose of optimizing their own transport capabilities and while as a whole, still provide the same level of service. An acceptable and fair method for allocating the costs and revenue according to the service provided by each company needs to be designed.

While in the former type, the transport demand is shared; in capacity sharing, it is the transport supply, which is shared. In other words, there is a temporary loan or borrowing of transport capacity, either in terms of load units (e.g. containers), transport units (e.g. vehicles or drivers), or logistics facilities (e.g. consolidation centres or cross-docks), or also of storage capacity, in terms primarily of warehousing space.

The third type, information sharing, occurs when carriers share information (often anonymized or aggregated to protect legal and business interests) with other partners to improve overall efficiency of operations. Such sharing might need a trusted third-party to collect, aggregate and process the data from the partners. The information could be used, for example, to optimize parking management at a busy street or a loading bay, such that competing carriers do not arrive at the same time.

Evaluation of City Logistics

In this video, Prof Taniguchi starts the series of lectures on evaluation of city logistics. Based on the a brief overview of the basic goals of city logistics, this video introduces three categories of city logistics policies with many examples.

Criteria for Evaluation

On what basis are evaluations made? Assistant Professor Ali presents here the typical evaluation criteria used in city logistics, such as cost, environment, social and congestion. It also describes some detailed components, normally, considered under each evaluation criteria.

Modeling of Urban Freight Flows

For many of the tasks in developing, evaluating and implementing sustainable urban freight concepts, we need to be able to model the freight flows. Freight traffic is embedded in a multi-layered economic and social context. Prof Tavasszy explains, in this video, the state-of-the-art models used in urban freight.

Key Takeaways

- Urban freight movement creates negative impacts, such as air and noise pollution, traffic accidents, congestion, and the emissions of greenhouse gases.

- A sustainable urban freight system balances the four key aspects (a) logistics service quality (b) general condition of the transport system (c) environmental concerns and impacts, and (d) social concerns

- An urban distribution system has three key dimensions (a) Stakeholders – administrators, residents, carriers, shippers, and receivers, (b) Spatial- site, link, regional, city, (c) Factors – financial, social, economic, environmental.

- There are four main approaches to improving the city logistics (a) creation of public/ private infrastructure (b) land use management (c) access conditions (d) traffic management.

Self-Test

Glossary: Key Terms

Consolidation: Freight consolidation is when a shipper combines multiple shipments within a region into a single load hauled by a carrier to a destination region.

Horizontal logistics: Horizontal logistics cooperation may be defined as “cooperation between two or more firms that are active at the same level of the supply chain and perform a comparable logistics function”. These firms serve the same transport service segment and provide almost the same services. Hence, they are very much rivals, in the fiercely competitive industry.

Logistics: logistics refers to the overall process of managing how resources are acquired, stored, and transported to their final destination.

Shuttle train: A shuttle train is a train that runs back and forth between two points, especially if it offers a frequent service over a short route.

Supply chain: A supply chain is the network of all the individuals, organizations, resources, activities and technology involved in the creation and sale of a product.

Transshipment: transshipment is the shipment of goods or containers to an intermediate destination, then to another destination.

Urban distribution: Urban freight distribution is the system and process by which goods are collected, transported, and distributed within urban environments. The urban freight system can include seaports, airports, manufacturing facilities, and warehouse/distribution centers that are connected by a network of railroads, rail yards, pipelines, highways, and roadways that enable goods to get to their destinations.

Media Attributions

Figures

- Figure 9.1: A Systems Approach to Urban Distribution from Sustainable Urban Freight Transport: a Global Perspective by through TU Delft OpenCourseWare is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike

Tables

- Table 9.1: Overview of main actions public administrators can perform and potential reactions from the private sector from Sustainable Urban Freight Transport: A Global Perspective is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Videos

- Video 1: Sustainable Urban Freight: Urban Freight Systems is available for free via http://www.online-learning.tudelft.nl ©️ TU Delft, released under a CC BY NC SA license: https://creativecommons.org/licences/…

- Video 2: Sustainable Urban Freight: Vehicle Technology is available for free via http://www.online-learning.tudelft.nl ©️ TU Delft, released under a CC BY NC SA license: https://creativecommons.org/licences/…

- Video 3: Sustainable Urban Freight: Urban Consolidation Centre is available for free via http://www.online-learning.tudelft.nl ©️ TU Delft, released under a CC BY NC SA license: https://creativecommons.org/licences/…

- Video 4: Sustainable Urban Freight: Evaluating the Impacts of City Logistics Policy Measures is available for free via http://www.online-learning.tudelft.nl ©️ TU Delft, released under a CC BY NC SA license: https://creativecommons.org/licences/…

- Video 5: Sustainable Urban Freight: Evaluating the Impacts of City Logistics Policy Measures is available for free via http://www.online-learning.tudelft.nl ©️ TU Delft, released under a CC BY NC SA license: https://creativecommons.org/licences/…

- Video 6: Sustainable Urban Freight: Modelling City Logistics is available for free via http://www.online-learning.tudelft.nl ©️ TU Delft, released under a CC BY NC SA license: https://creativecommons.org/licences/…

References

- Muñuzuri, J., Larrañeta, J., Onieva, L., & Cortés, P. (2005). Solutions applicable by local administrations for urban logistics improvement. Cities. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2004.10.003

- Sustainable Urban Freight Transport: a Global Perspective by TU Delft OpenCourseWare is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Attributions

-

- Transforming the Freight Industry in ACCESS Magazine, 1(20), 26-31 by Regan, A. is licensed by CC BY-NC 3.0

- Sustainable Urban Freight Transport: a Global Perspective by Dr. J.H.R. van Duin, Dr. Johan Joubert, Dr. Russell Thompson, Ir. Tharsis Teoh, Prof.dr.ir. L.A. Tavasszy through TU Delft OpenCourseWare is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike

Urban freight distribution is the system and process by which goods are collected, transported, and distributed within urban environments. The urban freight system can include seaports, airports, manufacturing facilities, and warehouse/distribution centers that are connected by a network of railroads, rail yards, pipelines, highways, and roadways that enable goods to get to their destinations.

Freight consolidation is when a shipper combines multiple shipments within a region into a single load hauled by a carrier to a destination region.

transhipment is the shipment of goods or containers to an intermediate destination, then to another destination.

Horizontal logistics cooperation may be defined as “cooperation between two or more firms that are active at the same level of the supply chain and perform a comparable logistics function”. These firms serve the same transport service segment and provide almost the same services. Hence, they are very much rivals, in the fiercely competitive industry.

A supply chain is the network of all the individuals, organizations, resources, activities and technology involved in the creation and sale of a product.