Chapter 1: The Basics of Sustainable Mobility

Sustainability has a broad definition and it varies from one discipline to another. This textbook defines sustainable mobility from the perspective of transportation engineering. We will train students to plan, design, operate, and maintain transportation-related infrastructure with the lens of sustainability as the primary focus. Th textbook was designed to use with a course that aims to teach students the current tools and technologies that have already been proven to reduce energy consumption and emissions from the transportation system. At the same time, we will introduce students to a blueprint to characterize, enhance, and integrate transportation technologies into transportation systems. This chapter lays down the overarching concept of this book.

Chapter Overview

The term “Sustainable Mobility” can be broken down into the terms “sustainable” and “mobility”. While sustainability has been defined in the literature in many ways, the meaning of sustainability in terms of mobility has specific nuances. In this chapter, we will start with the broader definition of sustainability. We will drill further down into specific transportation strategies that can improve the sustainability of the transportation system.

Chapter Topics

- Pillars of sustainability

- Sustainable transportation

- Reasons for unsustainable transportation

- Sustainable mobility strategies

Learning Objectives

At the end of the chapter, the reader should be able to do the following:

- Summarize the three pillars of sustainability.

- Acquire a basic facility for using the IPAT equation.

- Identify the strategies to promote sustainability in the transportation sector.

- Classify different metrics of sustainable transportation.

- Explain why the automobile-based system of transportation is unsustainable in terms of inputs, outputs, and social impacts

- Explain why transportation is a derived demand and how making transportation sustainable depends on land use as well as vehicles and infrastructure.

- Differentiate between accessibility and mobility by comparing how they are currently treated by our transportation system

- Analyze how a more sustainable system might address accessibility and mobility.

Sustainability

Sustainability is derived from two Latin words: sus which means up and tenere which means to hold. In its modern form it is a concept born out of the desire of humanity to continue to exist on planet Earth for a very long time, perhaps the indefinite future. Sustainability is, hence, essentially and almost literally about holding up human existence. Possibly, the most succinct articulation of the issue can be found in the Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. The report entitled “Our Common Future” primarily addressed the closely related issue of Sustainable Development. The report, commonly known as the Brundtland Report after the Commission Chair Gro Harlem Brundtland, stated that “Humanity has the ability to make development sustainable to ensure that it meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” Following the concept of Sustainable Development, the commission went on to add ”Yet in the end, sustainable development is not a fixed state of harmony, but rather a process of change in which the exploitation of resources, the direction of investments, the orientation of technological development, and institutional change are made consistent with future as well as present needs. We do not pretend that the process is easy or straightforward. Painful choices have to be made. Thus, in the final analysis, sustainable development must rest on political will.” Sustainability and the closely related concept of Sustainable Development are, therefore, very human constructs whose objective is to insure the very survival of humanity in a reasonably civilized mode of existence.

Pillars of Sustainability

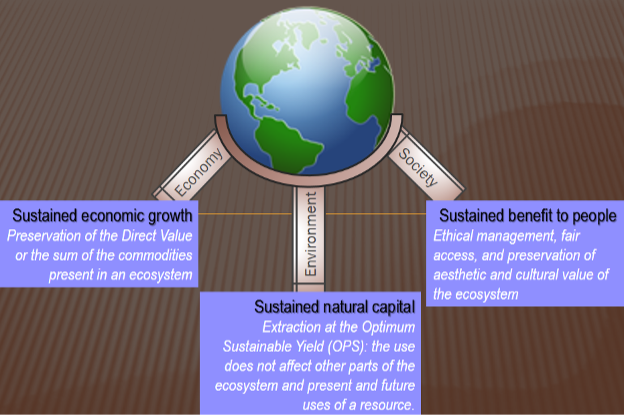

Achieving the goals of Sustainability requires a balance among three different bottom lines (shown in Figure 1.1), which are linked in very intricate ways. For example, the Great Recession of 2008 resulted in a temporary decrease of carbon emissions. However, tentative improvements in the economy have been accompanied by proportionally larger increments in emissions. Stricter regulations on the mining industry in the developed world resulted in mass migration of extractive industries to the developing world, with a net increment in environmental degradation and larger losses of environmental resources.

The Environmental Bottom Line limits the extraction and harvesting to levels at or below the Optimal Sustainable Yield and it addresses critical environmental concerns:

- Emissions. Minimize emission from fossil fuels and the impact of these emissions on global climate.

- Resources. Reverse the loss of environmental resources.

- Biodiversity. Decrease the rate of decline of biodiversity.

The Social Bottom Line addresses the ethical management of resources, issues of social stability, and the preservation of aesthetic and cultural values. Social stability requires universal access to:

Food. Feeding the world's population, which is projected to reach over 9 billion by 2050, requires a large increment of agricultural output. This is particularly important in the developing world, where production is limited and most of the population growth is predicted to occur. However, modern agricultural methods require vast losses of wild lands, drastic changes in ecosystems, and the introduction of large amounts of fertilizer and pesticides.

Safe drinking water and basic sanitation. Access to water that is microbially, chemically and physically safe for human and animal consumption, sanitation and hygiene remains a challenge in the developing world. In addition, depletion and pollution of surface and ground waters are an increasing concern in many developed nations including the United States.

The Economic Bottom Line aims at preserving the Direct Value of commodities present in an ecosystem. Sustainable economies are focused on curving poverty and incentivizing fair trade.

The IPAT Equation

As attractive as the concept of sustainability may be as a means of framing our thoughts and goals, its definition is rather broad and difficult to work with when confronted with choices among specific courses of action. Here we introduce one general way to begin to apply sustainability concepts: the IPAT equation.

As is the case for any equation, IPAT expresses a balance among interacting factors. It can be stated as

Equation:

I = P × A × T

where I represents the impacts of a given course of action on the environment, P is the relevant human population for the problem at hand, A is the level of consumption per person, and T is impact per unit of consumption. Impact per unit of consumption is a general term for technology, interpreted in its broadest sense as any human-created invention, system, or organization that serves to either worsen or uncouple consumption from impact. The equation is not meant to be mathematically rigorous; rather it provides a way of organizing information for a “firstorder” analysis.

Suppose we wish to project future needs for maintaining global environmental quality at present day levels for the mid-twenty-first century. For this we need to have some projection of human population (P) and an idea of rates of growth in consumption (A).

The global population in 2050 will grow from the current 8 billion to about 9.2 billion, an increase of 35%. Global GDP (Gross Domestic Product, one measure of consumption) varies from year to year but, using an annual growth rate of about 3.5% seems historically accurate (growth at 3.5%, when compounded for forty years, means that the global economy will be four times as large at mid-century as today).

Thus if we wish to maintain environmental impacts (I) at their current levels, then

Equation:

P2023 x A2023 x T2023 = P2050 x A2050 x T2050

Or

Equation:

[latex]\frac{T_{2050}}{T_{2023}}=\ \frac{P_{2023}}{P_{2050}}\ \times\ \frac{A_{2023}}{A_{2050}}=\ \frac{1}{1.35}\ \times\frac{1}{4}=\ \frac{1}{5.4}[/latex]

This means that just to maintain current environmental quality in the face of growing population and levels of affluence, our technological decoupling will need to reduce impacts by about a factor of five. So, for instance, many recently adopted “climate action plans” for local regions and municipalities, such as the Chicago Climate Action Plan, typically call for a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (admittedly just one impact measure) of eighty percent by mid-century. The means to achieve such reductions, or even whether or not they are necessary, are matters of intense debate; where one group sees expensive remedies with little demonstrable return, another sees opportunities for investment in new technologies, businesses, and employment sectors, with collateral improvements in global and national well-being.

What is Sustainable Transportation?

Transportation is a tricky thing to analyze in the context of sustainability. It consists in part of the built environment: the physical infrastructure of roads, runways, airports, bridges, and rail lines that makes it possible for us to get around. It also consists in part of individual choices: what mode we use to get around (car, bus, bike, plane, etc.), what time of day we travel, how many people we travel with, etc. Finally, it also is made up of institutions: federal and state agencies, oil companies, automobile manufacturers, and transit authorities, all of whom have their own goals and their own ways of shaping the choices we make.

Most importantly, transportation is complicated because it’s what is called a derived demand. With the exception of joyriding or taking a walk or bicycle ride for exercise, very rarely are we traveling just for the sake of moving. We’re almost always going from Point A to Point B. What those points are—home, work, school, shopping—and where they’re located—downtown, in a shopping mall, near a freeway exit—influence how fast we need to travel, how much we can spend, what mode we’re likely to take, etc. The demand for transportation is derived from other, non-transportation activities. So in order to understand transportation sustainability, we have to understand the spatial relationship between where we are, where we want to go, and the infrastructure and vehicles that can help get us there.

Is our current transportation system in the U.S. sustainable? In other words, can we keep doing what we’re doing indefinitely? The answer is clearly no, according to professional planners and academics alike. There are three main limitations: energy input, emissions, and social impacts (Black, 2010).

Energy Inputs

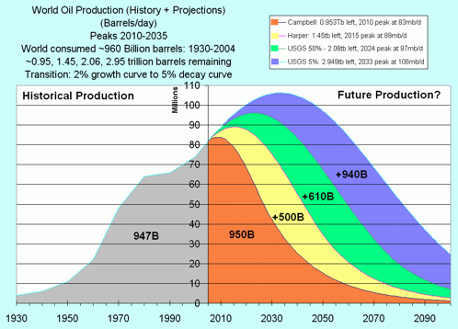

The first reason that our current transportation system is unsustainable is that the natural resources that power it are finite. The theory of peak oil developed by geologist M. King Hubbert suggests that because the amount of oil in the ground is limited, at some point in time there will be a maximum amount of oil being produced (Deffeyes, 2002). After we reach that peak, there will still be oil to drill, but the cost will gradually rise as it becomes a more and more valuable commodity. The most reliable estimates of the date of peak oil range from 2005 to 2015, meaning that we’ve probably already passed the point of no return. New technologies do make it possible to increase the amount of oil we can extract, and new reserves, such as the oil shale of Pennsylvania and the Rocky Mountains, can supply us for some years to come (leaving aside the potential for environmental and social damage from fully developing these sites). However, this does not mean we can indefinitely continue to drive gasoline-powered vehicles as much as we currently do.

Scientists are working on the development of alternative fuels such as biofuels or hydrogen, but these have their own limitations. For example, a significant amount of land area is required to produce crops for biofuels; if we converted every single acre of corn grown in the U.S. to ethanol, it would provide 10% of our transportation energy needs. Furthermore, growing crops for fuel rather than food has already sparked price increases and protests in less-developed countries around the world (IMF, 2010). Is it fair to ask someone living on less then two dollars a day to pay half again as much for their food so we can drive wherever and whenever we want?

Emissions or Outputs

The engine of the typical automobile or truck emits all sorts of noxious outputs. Some of them, including sulfur dioxides, carbon monoxide, and particulate matter, are directly harmful to humans; they irritate our lungs and make it hard for us to breathe. (Plants are damaged in much the same way). These emissions come from either impure fuel or incomplete burning of fuel within an engine. Other noxious outputs cause harm indirectly. Nitrous oxides (the stuff that makes smog look brown) from exhaust, for example, interact with oxygen in the presence of sunlight (which is why smog is worse in Los Angeles and Houston), and ozone also damages our lungs.

Carbon dioxide, another emission that causes harm indirectly, is the most prevalent greenhouse gas (GHG), and transportation accounts for 23% of the CO2 generated in the U.S. This is more than residential, commercial, or industrial users, behind only electrical power generation (DOE, 2009). Of course, as was explained above, transportation is a derived demand, so to say that transportation itself is generating carbon emissions is somewhat misleading. The distance between activities, the modes we choose to get between them, and the amount of stuff we consume and where it is manufactured, all contribute to that derived demand and must be addressed in order to reduce GHG emissions from transportation.

Social Impacts

If the definition of sustainability includes meeting the needs of the present population as well as the future, our current transportation system is a failure. Within most of the U.S., lack of access to a personal automobile means greatly reduced travel or none at all. For people who are too young, too old, or physically unable to drive, this means asking others for rides, relying heavily on under-funded public transit systems, or simply not traveling. Consider, for example, how children in the U.S. travel to and from school. In 1970, about 50% of school-aged children walked or biked to school, but by 2001, that number had dropped to 15% (Appleyard, 2005). At the same time that childhood obesity and diabetes are rising, children are getting less and less exercise, even something as simple as walking to school. Furthermore, parents dropping off their children at school can increase traffic levels by 20 to 25%, not just at the school itself, but also throughout the town in question (Appleyard, 2005). At the other end of the age spectrum, elderly people may be functionally trapped in their homes if they are unable to drive and lack another means of getting to shopping, health care, social activities, etc. Finally, Hurricane Katrina made it clear that access to a car can actually be a matter of life or death: the evacuation of New Orleans worked very well for people with cars, but hundreds died because they didn’t have the ability to drive away.

Another serious social impact of our transportation system is traffic accidents. Road accidents and fatalities are accepted as a part of life, even though 42,000 people die every year on the road in the U.S. This means that cars are responsible for more deaths than either guns, drugs, or alcohol (Xu et al., 2010). On the bright side, there has been a steady reduction in road fatalities over the last few decades, thanks to a combination of more safety features in vehicles and stricter enforcement and penalties for drunk or distracted drivers. Nevertheless, in many other countries around the world, traffic accidents are in the top ten or even top five causes of death, leading the World Health Organization to consider traffic accidents a public health problem.

An additional problem with our current unsustainable transportation system is that much of the rest of the world is trying to emulate it. The U.S. market for cars is saturated, meaning that basically everyone who can afford or is likely to own a car already has one. This is why automobile manufacturers vie so fiercely with their advertising, because they know they are competing with each other for pieces of a pie that’s not getting any bigger. In other countries such as China and India, though, there are literally billions of people who do not own cars. Now that smaller, cheaper vehicles like the Tata are entering these markets, rates of car ownership are rising dramatically. While the same problems with resources, emissions, and social impacts are starting to occur in the developing world, there are also unique problems. These include a lack of infrastructure, which leads to monumental traffic jams; a need for sharing the road with pedestrians and animals; and insufficient regulation to keep lead and other harmful additives out of gasoline and thus the air.

What Would Make Transportation Sustainable?

The circular answer to the question is to meet our current transportation needs without preventing future generations from meeting theirs. We can start by using fewer resources or using the ones we have more efficiently. One way to do this is by increasing the efficiency of new vehicles as they are manufactured. Since 1981, automotive engineers have figured out how to increase horsepower in the average American light-duty vehicle (cars and SUVs) by 60%, but they haven’t managed to improve miles per gallon at all (see Figure World Oil Production – History and Projections). As gas prices continue to rise on the downside of the oil peak, consumers are already demanding more fuel-efficient cars, and federal legislation is moving in this direction to raise the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards.

However, simply producing more fuel-efficient vehicles is not sufficient when we consider the embodied energy of the car itself. It takes a lot of energy to make a car, especially in the modern "global assembly line," where parts come from multiple countries for final assembly, and that energy becomes "embodied" in the metal, plastic, and electronics of the car. A study in Europe found that unless a car is over 20 years old, it does not make sense to trade it in for a more efficient one because of this embodied energy (Usón et al., 2011). Most Americans trade in their cars after about a third of that time. A related concept is true for electric cars. In their daily usage, they generate zero carbon emissions, but we should also consider the source of power used to recharge the vehicle. In most parts of the U.S., this is coal, and therefore the emissions savings are only about 30% over a traditional vehicle (Marsh, 2011).

If transportation is a derived demand, another way to meet our current transportation needs is by changing the demand. There are two related aspects to this. First, there is a clear causal link between having more transportation infrastructure and more miles traveled on that infrastructure, and greater economic growth. This is true between regions of the world, between individual countries, and between people and regions within countries. This causal connection has been used as a reason to finance transportation projects in hundreds of different contexts, perhaps most recently in the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act that distributed federal funds to states and localities to build infrastructure in the hopes that it would create jobs. Policymakers, businesspeople, and citizens therefore all assume that we need more transportation to increase economic growth.

However, it is also true that more transportation does not automatically mean more economic growth: witness the state of West Virginia, with decades' worth of high-quality road infrastructure bestowed upon it by its former Senator Robert Byrd, but still at the bottom of economic rankings of states. Furthermore, at some point a country or region gains no significant improvements from additional infrastructure; they have to focus on making better use of what they already have instead. We therefore need to decouple economic growth from transportation growth (Banister and Berechman, 2001). We can substitute telecommunication for travel, work at home, or shop online instead of traveling to a store (although the goods still have to travel to our homes, this is more efficient than each of us getting in our own cars). We can produce the goods we use locally instead of shipping them halfway around the world, creating jobs at home as well as reducing resource use and emissions. All of these options for decoupling are ways to reduce the demand for transportation without also reducing the benefits from the activities that create that demand.

The other way to think about changing the derived demand of transportation is via the concepts of accessibility and mobility. Mobility is simply the ability to move or to get around. We can think of certain places as having high accessibility: at a major intersection or freeway exit, a train station, etc. Company headquarters, shopping malls, smaller businesses alike decide where to locate based on this principle, from the gas stations next to a freeway exit to the coffee shop next to a commuter rail station. At points of high accessibility, land tends to cost more because it's easier for people to get there and therefore more businesses or offices want to be there. This also means land uses are usually denser: buildings have more stories, people park in multi-level garages instead of surface lots, etc.

We can also define accessibility as our own ability to get to the places we want: where we shop, work, worship, visit friends or family, see a movie, or take classes. In either case, accessibility is partially based on what the landscape looks like—width of the roads, availability of parking, height of buildings, etc.—and partially on the mode of transportation that people have access to. If a person lives on a busy four-lane road without sidewalks and owns a car, most places are accessible to him. Another person who lives on that same road and doesn't have a car or can't drive might be literally trapped at home. If her office is downtown and she lives near a commuter rail line, she can access her workplace by train. If her office is at a major freeway intersection with no or little transit service, she has to drive or be driven.

Unfortunately, in the U.S. we have conflated accessibility with mobility. To get from work to the doctor's office to shopping to home, we might have to make trips of several miles between each location. If those trips are by bus, we might be waiting for several minutes at each stop or making many transfers to get where we want to go, assuming all locations are accessible by transit. If those trips are by car, we are using the vehicle for multiple short trips, which contributes more to air pollution than a single trip of the same length. Because of our land use regulations, which often segregate residential, retail, office, and healthcare uses to completely different parts of a city, we have no choice but to be highly mobile if we want to access these destinations. John Urry has termed this automobility, the social and economic system that has made living without a car almost impossible in countries like the US and the UK (2004).

So how could we increase accessibility without increasing mobility? We could make it possible for mixed uses to exist on the same street or in the same building, rather than clustering all similar land uses in one place. For example, before a new grocery store opened in the student neighborhood adjacent to the University of Illinois campus in Champaign, people living there had to either take the bus, drive, or get a friend to drive them to a more distant grocery store. Residents of Campustown had their accessibility to fresh produce and other products increase when the new grocery store opened, although their mobility may have actually gone down. In a large scale example, the Los Angeles Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) was sued in the 1990s for discriminating against minorities by pouring far more resources into commuter rail than into buses. Commuter rail was used mainly by white suburbanites who already had high levels of accessibility, while the bus system was the only means of mobility for many African American and Hispanic city residents, who had correspondingly less accessibility to jobs, shopping, and personal trips. The courts ruled that the transit authority was guilty of racial discrimination because they were providing more accessibility for people who already had it at the expense of those who lacked it. The MTA was ordered to provide more, cleaner buses, increase service to major job centers, and improve safety and security. More sustainable transportation means ensuring equitable accessibility — not mobility — for everyone now and in the future.

Strategies for Sustainable Transportation

How do we go about making transportation more sustainable? There are three main approaches: inventing new technologies, charging people the full costs of travel, and planning better so we increase accessibility but not mobility.

New Technology

This is the hardest category to rely on for a solution, because we simply can't predict what might be invented in the next five to fifty years that could transform how we travel. The jet engine totally changed air travel, making larger planes possible and increasing the distance those planes could reach without refueling, leading to the replacement of train and ship travel over long distances. However, the jet engine has not really changed since the 1960s. Is there some new technology that could provide more propulsion with fewer inputs and emissions? It's possible. But at the same time, it would be unreasonable to count on future inventions magically removing our sustainability problems rather than working with what we already have.

Technology is more than just machines and computers, of course; it also depends on how people use it. When the automobile was first invented, it was seen as a vehicle for leisure trips into the country, not a way to get around every day. As people reshaped the landscape to accommodate cars with wider, paved roads and large parking lots, more people made use of the car to go to work or shopping, and it became integrated into daily life. The unintended consequences of technology are therefore another reason to be wary about relying on new technology to sustain our current system.

Charge Fuel Costs

The economist Anthony Downs has written that traffic jams during rush hour are a good thing, because they indicate that infrastructure is useful and a lot of people are using it (Downs, 1992). He also notes that building more lanes on a highway is not a solution to congestion, because people who were staying away from the road during rush hour (by traveling at different times, along different routes, or by a different mode) will now start to use the wider road, and it will become just as congested as it was before it was widened. His point is that the road itself is a resource, and when people are using it for free, they will overuse it. If instead, variable tolls were charged depending on how crowded the road was—in other words, how much empty pavement is available—people would choose to either pay the toll (which could then be invested in alternative routes or modes) or stay off the road during congested times. The point is that every car on the road is taking up space that they aren't paying for and therefore slowing down the other people around them; charging a small amount for that space is one way of recovering costs.

Traffic congestion is an example of what economists call externalities, the costs of an activity that aren't paid by the person doing the activity. Suburbanites who drive into the city every day don't breathe the polluted air produced by their cars; urban residents suffer that externality. People around the country who use gasoline derived from oil wells in the Gulf of Mexico didn't experience oil washing up on their beaches after the BP disaster in 2010. By charging the full cost of travel via taxes on gas or insurance, we could, for example, pay for children's hospitalization for asthma caused by the cars speeding past their neighborhoods. Or we could purchase and preserve wetland areas that can absorb the floodwaters that run off of paved streets and parking lots, keeping people's basements and yards drier. Not only would this help to deal with some of the externalities that currently exist, but the higher cost of gas would probably lead us to focus on accessibility rather than mobility, reducing overall demand.

Planning Better for Accessibility

The other way we can produce more sustainable transportation is to plan for accessibility, not mobility. Many transportation planners say that we've been using the predict and provide model for too long. This means we assume nothing will change in terms of the way we travel, so we simply predict how much more traffic there is going to be in the future and provide roads accordingly. Instead, we should take a deliberate and decide approach, bringing in more people into the planning process and offering different options besides more of the same. Some of the decisions we can make to try and change travel patterns include installing bike lanes instead of more parking, locating retail development next to housing so people can walk for a cup of coffee or a few groceries, or investing in transit instead of highways.

For example, the school district in Champaign, Illinois, is considering closing the existing high school next to downtown, to which many students walk or take public transit, and replacing it with a much larger facility on the edge of town, to which everyone would have to drive or be driven. The new site would require more mobility on the part of nearly everyone, while many students and teachers would see their accessibility decrease. As gas prices continue to rise, it will cost the school district and parents more and more to transport students to and from school, and students will be more likely to drive themselves if they have access to a car and a driver's license. Putting the new school in a more accessible location or expanding the existing one would keep the school transportation system from becoming less sustainable.

You may have noticed that these proposed changes to increase transportation sustainability aren't really things that one person can do. We can certainly make individual choices to drive less and walk or bike more, to buy a more fuel-efficient car, or to use telecommunications instead of transportation. In order to make significant changes that can reduce overall energy usage and emissions production, however, the system itself has to change. This means getting involved in how transportation policy is made, maybe by attending public meetings or writing to city or state officials about a specific project. It means contacting your Congressional representatives to demand that transportation budgets include more money for sustainable transportation modes and infrastructure. It means advocating for those who are disadvantaged under the current system. In means remembering that transportation is connected to other activities, and that focusing on how the demand for transportation is derived is the key to making and keeping it sustainable.

Key Takeaways

- Achieving the goals of Sustainability requires a balance among three different bottom lines – economy (profit) , environment (planet), and society (people).

- The demand for transportation is derived from other, non-transportation activities.

- There are three major dimensions of unsustainable transportation- dependence on non-renewable fuel, emissions of deleterious materials, and social impacts or externalities such as congestion, crashes, etc.

- More sustainable transportation means ensuring equitable accessibility — not mobility — for everyone now and in the future.

- There are three main approaches to increase transportation sustainability: inventing new technologies, charging people the full costs of travel, and planning for multimodal accessibility.

Self-Test

Glossary: Key Terms

Accessibility: In transportation, a measure of the ease with which people are able to get places they want or need to go.

Derived demand: Demand for a good or service that comes not from a desire for the good or service itself, but from other activities that it enables or desires it fulfills.

Embodied energy: The sum of all energy used to produce a good, including all of the materials, processes, and transportation involved.

Externality: Cost of an activity not paid by the person doing the activity.

Mobility: The ability to move or to get around.

Sustainable development: Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

Media Attributions

- Figure 1.1: Three pillars of sustainability by Neyda Abreu is under the following Creative Commons license: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

- Figure 1.2: World Oil Production- History and Projections by Tom Ruen is under the Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 1.3: Freeway Traffic by User Minesweeper via Wikimedia Commons is under the following Creative Commons license: CC-BY-SA-3.0

References

- Appleyard, B. S. 2005. Livable Streets for School Children: How Safe Routes to School programs can improve street and community livability for children. National Centre for Bicycling and Walking Forum, available online: https://www.safetylit.org/citations/index.php?fuseaction=citations.viewdetails&citationIds[]=citjournalarticle_476088_9

- Banister, D. and Berechman, Y. 2001. Transport investment and the promotion of economic growth. Journal of Transport Geography 9:3, 209-218.

- Black, W. 2010. Sustainable Transportation: Problems and Solutions. New York: Guilford Press.

- Deffeyes, K. 2002. Hubbert’s Peak: The Impending World Oil Shortage. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- DOE (Department of Energy). 2009. Emissions of greenhouse gases report. DOE/EIA-0573, available online: http://www.eia.doe.gov/oiaf/1605/ggrpt/carbon.html

- Downs, A. 1992. Stuck in Traffic: Coping With Peak-Hour Traffic Congestion. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2010. Impact of high food and fuel prices on developing countries. Available online: http://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/faq/ffpfaqs.htm

- Marsh, B. 2011. Kilowatts vs. Gallons. New York Times, May 28. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2011/05/29/weekinreview/volt-graphic.html?ref=weekinreview

- Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. 1987. www.un-documents.net/wced-ocf.htm.

- UPI (United Press International). 2011. Global biofuel land area estimated. Available online: http://www.upi.com/Science_News/2011/01/10/Global-biofuel-land-area-estimated/UPI-97301294707088/

- Urry, J,. 2004. The ‘System’ of Automobility. Theory Culture and Society 21:4-5, 25-39.

- Usón, A.A., Capilla, A.V., Bribián, I.Z., Scarpellini, S. and Sastresa, E.L. 2011. Energy efficiency in transport and mobility for an eco-efficiency viewpoint. Energy 36:4, 1916-23.

- Xu, J., Kochanek, K., Murphy, S., and Tejada-Vera, B. 2010. Deaths: Final Data for 2007. National Vital Statistics Reports, 58:19, available online: http://www.cdc.gov/NCHS/data/nvsr/nvsr58/nvsr58_19.pdf

Attributions

- Foundations in Sustainability Systems (EME 504) by Neyda Abreu is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

- Sustainability: A Comprehensive Foundation by Tom Theis and Jonathan Tomkin is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

Demand for a good or service that comes not from a desire for the good or service itself, but from other activities that it enables or desires it fulfills.

The sum of all energy used to produce a good, including all of the materials, processes, and transportation involved.

In transportation, a measure of the ease with which people are able to get places they want or need to go.

The ability to move or to get around.

Cost of an activity not paid by the person doing the activity.