2 Selecting Aligned Assessments

Jessica Kahlow

Assessment is a crucial element in enhancing the overall quality of teaching and learning in higher education. What and how students learn depends to a major extent on how they think they will be assessed (Biggs & Tang, 2007). All assessments lead to some amount of student learning, but a fundamental challenge lies in stimulating the right kind of learning. Therefore, it is important that assessment practices are designed to send the right signals to students in shaping the effectiveness of student learning – about what they should learn and how they should learn.

From a student’s perspective, the relationship between learning and assessment often comes down to one thing: a grade (McMorran, Ragupathi and Simei, 2015). This problem arises simply because an assessment is usually about several things at once and Boud (2000) refers to this as ‘double duty’. It is about grading and about learning; it is about evaluating student achievements and teaching them better; it is about standards and invokes comparisons between individuals; it communicates explicit and hidden messages.

Assessment has multiple purposes that include providing feedback on learning, facilitating improvement, measuring achievement, motivating learning, and maintaining standards. Always worry about the quality of assessments rather than their quantity. Well-designed assessment tasks will influence how students approach the problems and thereby improve the quality of their learning. Thus, the level of student engagement and the amount of time students invest in any given learning experience is directly related to how much the student believes they will benefit from this experience.

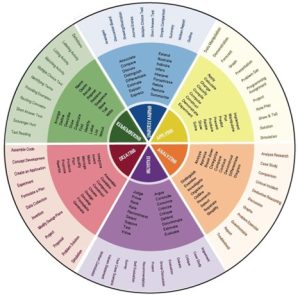

It’s a good reminder here for how to determine the assessment type before you start creating all the assessment details.

- In the middle section of the wheel, find the action verb your objective uses.

- Once you find the location of your verb, look at the outer portion of that section and review the assessments listed.

- Choose an assessment.

- Check yourself: What if you don’t see an assessment you want to use? Do you see the assessment you do want to use under a different section of the circle? If so, it looks like there may be a problem with the alignment of your objective and assessment. Perhaps you need to rewrite your objective to use a different action verb.

Crawford, Stephen (2012). Aligning Assessments with Learning Objectives. http://teachonline.asu.edu/2012/10/aligning-assessments-with-learning-objectives/.

Types of Online Assessments

| Assessment Type | Examples | Possible Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Written Assignments | Essays, Case studies, Reflections, Journals, Article Reviews, Literature Reviews Proposals, Research Papers, Reports, Summaries, ePortfolios | Canvas Assignments, Canvas Rubrics Microsoft Word, PowerPoint, Blogs/wikis, etc. |

| Online Discussions | Presentations, Peer Reviews, Case Studies, Analysis, Reflections, etc. | Canvas Discussions |

| Graded Quizzes | Online Quizzes (MCQs, MRQs, FIBs, T/F, matching, ordering), in-video quizzes, short answer questions | Canvas Quizzes, H5P, Quizlet, Genially, etc. |

| Ungraded Quizzes | Online Quizzes (MCQs, MRQs, FIBs, T/F, matching, ordering), in-video quizzes | H5P, Quizlet, Genially, etc. |

According to the constructive alignment theory by Biggs and Tang (2007), assessment tasks (AT) and teaching-learning activities (TLA) are designed to ensure that students achieve the intended learning outcomes (ILO) and develop cognitive skills at a range of levels. The learning outcomes for a topic/unit are the criteria against which instructors make judgments about student learning. The introduction of a series of in-class teaching-learning activities and online tests/assignments that allow students to practice applying information, and the repetitive use of these skills that are spaced in regular intervals makes a difference in students’ learning.

Assessment tasks need to be aligned to the learning outcomes we intend to address for a particular topic, and an appropriate AT should indicate how well a student has achieved the ILO(s) it is meant to address and/or how well the task itself has been performed. A range of assessment types ensures that students develop all of the intended learning outcomes and also provides opportunities for students to demonstrate their learning.

Well-designed assessments set clear expectations, establish a reasonable workload, and provide opportunities for students to self-learn, rehearse, practice, and receive feedback. However, when designed poorly they can be a major hindrance to thinking and learning in our students. Assessments should be able to provide students with feedback on their progress and be able to help them identify their readiness to proceed to the next level of the module. Therefore, assessment tasks need to be aligned with intended learning outcomes (ILOs) and should be designed in such a way that they:

- Elicit higher-order cognitive skills

- Develop a consequential basis for test score interpretation and use

- Are fair, and free of bias

- Can be generalized and transferable, at least across topics within a domain

- Ensure the quality of content is consistent with the best current understanding of the field

- Recognize the comprehensiveness, or scope, of content coverage

- Are high-fidelity assessments of critical abilities

- Are contextualized and meaningful to students’ educational experiences.

- Are practical, efficient, and cost-effective

The above set of criteria is not exhaustive but provides a guideline that is consistent with both current theoretical understandings of validity and the nature and potential uses of new forms of assessment (Linn et al, 1991; Darling-Hammond et al., 2013).

Bloom’s Taxonomy of educational objectives (Table 1) can also serve as a useful reminder when designing assessment tasks. Holtzman (2008) provides a quick summary of the six levels in Bloom’s taxonomy, and how these six skill levels build on each other.

When following the Quality Matters (QM) Rubric, you’ll find the recommendation to make sure assessments are varied, sequenced, and suited to the level of the course. Here’s what each of those mean:

- variety: According to QM, “… provide multiple ways for learners to demonstrate progress and mastery, and to accommodate diverse learners”. Some students may do better at written assignments because multiple choice tests give them test anxiety. Vice versa, some students may struggle with written assignments (maybe English is their second language) and so they prefer multiple choice tests.

- sequence: According to QM, “… assessments are sequenced so as to promote the learning process and to build on previously mastered knowledge and skills gained in this course and prerequisite courses. Assessments are paced to give learners adequate time to achieve mastery and complete the work in a thoughtful manner.” For example, students may start off with simple quiz questions to identify key concepts from the week’s readings. Then, once they have mastered identifying and recalling information about the concepts, they are ready to apply the concepts on a discussion or real-life example problem. Another example is sequencing of a final project. Students may start by turning in an outline, then an introduction and bibliography or a first draft, and then the final version of the project.

- suited to the level of the course: While you do want to make sure assessments reflect varying levels of cognitive engagement in every course, the level of the course can dictate how much it is skewed. For example, in a lower-level course it may be ok for most of the assessments to measure students remembering basic facts; but, assessments in an upper-level course should include more assessments that are at the application level or above.

How to Complete the Course Map

The course map provides a detailed outline of your entire course. Its purpose is two-fold. First, it helps make sure you and your instructional designer (ID) are on the same page as you begin putting your course into Canvas. Second, it helps show alignment for both students and the QM review process. So, it’s an important first step, and you can’t move on to developing your course until your ID approves your course map.

It is a lengthy and time-consuming process, and most course maps need to be reviewed by the ID 3-4 times before they are complete. Most course maps end up being at least three pages long. It is important that you stick to your course map as you develop your course, but you can make changes to it; we’ll ask for a finalized course map at the end of the process.

This guide will help you develop your course map.

Course Outcomes

Make sure course objectives are measurable (use verbs from the lists below).

Below is a list of measurable verbs from Bloom’s taxonomy that are most often used for course and module objectives.

| Knowledge | Understand | Apply | Analyze | Evaluate | Create |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| classify

define describe enumerate identify label list locate match name recall recite record repeat select |

compare

contrast describe differentiate discuss distinguish explain group interpret order organize outline paraphrase summarize translate |

apply

calculate change combine collect complete compute demonstrate explain illustrate interpret practice relate solve use |

analyze

classify compare contrast correlate diagram differentiate dissect distinguish estimate explain illustrate order organize separate |

appraise

argue assess critique debate decide estimate evaluate grade judge justify measure predict rate recommend |

collaborate

construct create design develop facilitate integrate make manage plan prepare present propose simulate write |

Table adapted from UTA Center for Distance Education. (2023). CDE Measurable Verbs. https://uta.instructure.com/courses/143147/pages/measurable-verbs?module_item_id=7039880. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Action Verbs to Avoid because they are NOT measurable

There are some action verbs that should be avoided. Those are:

- understand

- reflect

- demonstrate understanding

- become aware of

- increase awareness of

- explore

- know

- learn

- appreciate

- demonstrate an appreciation of

These verbs are not the task students will be doing to demonstrate mastery on the graded assignment. For example, to measure understanding, students might be identifying on a multiple choice test or explaining on a written assignment, and therefore identify or explain is a better action verb.

Module Outcomes

Focus on what you want students to have learned by the time they finish the module. A good place to start thinking about these might be your textbook chapters; they often have objectives already listed at the beginning of chapters.

Your module objectives should also use Bloom’s verbs and they should use a verb at the same level or lower than the course objective. For example, if the course objective starts with “analyze” a module objective could include any verb from the analyze, apply, understand, or knowledge categories.

Make sure they are measurable (use a verb from the lists provided above).

Make sure there is only one module objective per row. This means that each module will have more than one row.

Make sure they’re not tasks. If they are tasks, then they are likely an activity or an assessment (see below).

Materials (readings, videos, etc.)

Materials include anything that you give students to learn the materials. This includes textbook chapters, journal articles, other reading materials, recorded lectures, other videos, podcasts, etc.

Be sure to list out each reading separately and say what it is. For example, “Read textbook chapter 3.”

Selecting inclusive instructional materials

It is also important to include a variety of instructional materials so that your course isn’t entirely text-based. According to Quality Matters, there should be “options for how they [learners] consume content, e.g., reading an article or text, viewing a video, listening to a podcast.” Some students digest content better when watching versus reading and vice versa.

Variety doesn’t just mean variety in text versus audio/video, but also in perspectives. It’s good to provide content from multiple authors and multiple perspectives (if multiple perspectives exist). This culturally responsive pedagogy is a part of having variety among your course materials. This is also things like making sure your course isn’t completely text-based, citing your sources, having current materials, and having a variety of assessments, preferably one per module, even if it’s a low-stakes assessment.

Whether you are curating or developing content, it is important to always consider the inclusivity of the materials. Read each item below to learn more about how to make sure your instructional materials are inclusive.

1. Select content that engages a diversity of ideas and perspectives

One of the best ways to make sure your content is diverse and inclusive is to choose interesting, engaging, and relevant content. When choosing readings, texts, and other materials, think about whether any perspectives are missing or underrepresented. You want students to be able to think about course materials from a variety of different perspectives. So, it’s important to recognize how your choice of materials reflects your perspectives, interests, and possible biases. Always analyze the content of your examples, analogies, and humor; too narrow a perspective may ostracize students who have differences.

If you do assign something that could be problematic or that uses stereotypes, be sure to point out those shortcomings and consider supplementing those readings with other materials that show other perspectives. This also encourages students to critique content, which also helps promote critical thinking. You can also use this as an opportunity to teach students about the conflicts present within the field by incorporating those diverse perspectives.

2. Select content by authors with diverse backgrounds

When selecting course content, include materials written, created, or researched by authors of diverse backgrounds relevant to the topics in the course. For example, if all of the articles in your course were conducted by male European or American scientists, you may send a message (even if inadvertent) to students that there is no scholarship produced by women and people of color, or perhaps worse, that you do not value it. If applicable, discuss contributions made to the field by historically underrepresented groups and explain why these efforts are significant. This can validate students by helping them see themselves represented by the authors of the course (Appert et al., 2017).

Whenever possible, instructors should broaden readings by including some from non-dominant perspectives. However, you should also avoid including just a token marginalized perspective here or there just to comply with a diversity best practice instead of meaningfully including and considering different perspectives. Inclusive course readings should place multiple perspectives at the center and should be carefully and thoughtfully contextualized and integrated (Appert et al., 2017).

3. Offer a variety of representative instructional materials

Offering a variety of course materials is an inclusive best practice and a general teaching best practice. Standard 4.5 of the QM rubric states “a variety of instructional materials is used in the course”, and the Universal Design for Learning model also stresses the importance of presenting information in a variety of formats because not everyone learns or processes information in the same way; this it increases the cognitive accessibility of the materials, provides students flexibility in how they learn, and increases student engagement (Brooks & Grady, 2022).

This means that you should use a variety of teaching methods. Your course shouldn’t be entirely text-based because not every student learns best by reading. Instead, supplement your readings with recorded lecture videos, overview videos, other pre-existing videos (that you didn’t create), podcasts, images, and other activities. When selecting visuals, try to choose visuals that include diverse participants.

4. Use relevant and diverse examples

When choosing materials and examples (and test questions, assignments, and case studies) to use in your course, be sure to use examples that speak across genders and cultures and that are relatable to people from various socio-cultural contexts in a way that doesn’t marginalize students. Provide representative exemplars through the selection of texts, guest speakers, and leaders that allow students to imagine their future successful selves.

If you cannot, ground examples in specificity and discuss limitations. Don’t assume that all students will recognize the cultural, literary, or historical references you use. Make sure not to reward students for their similarity to you at the expense of others. Instead, draw on resources, materials, humor, and anecdotes that are relevant to the subject, and sensitive to the social and cultural diversity of your students (Appert et al., 2017). Make connections from the content to learners’ lived experiences when possible (e.g., provide examples of genetic diseases familiar to learners when discussing the topic of chromosomal abnormalities).

5. Ensure all materials work together to promote diverse ways of knowing

Make sure the instructional materials, assessments, learning activities, and tools you develop/select all support the learning outcomes. This intentional curricular alignment should integrate and encourage diverse ways of knowing.

As you begin to create content, always keep alignment and the course’s learning objectives in mind. Alignment is the idea that all critical course components work together to ensure that learners achieve the desired learning outcomes. This best practice also aligns with QM standards 4.1 and 4.2, which state that “instructional materials contribute to the achievement of the stated learning objectives” and “the relationship between the use of instructional materials and learning activities in the course is explained”, respectively.

You can ensure alignment with backward design by following these three basic steps:

- Write measurable, action-oriented learning objectives that address the appropriate level of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

- Choose assessment methods that indicate students’ mastery of the objectives and materials.

- Choose instructional materials that help students work towards those objectives.

6. Make all content accessible to all students

Another question to always keep in mind as you are developing and curating content, is “Are these materials/activities accessible for all learners?” Are images and other visuals described in text? Are headings properly formatted as headings or are they just bigger, bolder fonts?

As you may recall, accessibility is also present in the QM rubric; standards 8.3 and 8.4 state that the “course provides accessible text and images in files, documents, LMS pages, and web pages to meet the needs of diverse learners” and “the course provides alternative means of access to multimedia content in formats that meet the needs of diverse learners”, respectively.

Using diverse, inclusive, and equitable content can help improve the learning experience for all learners.

Keep in mind that not all of these will always be appropriate for every class, but you should still be able to find yourself able to incorporate at least a few of them.

1. Allow students to demonstrate learning in multiple ways

One way to do this would be to include varying assignment types (e.g., quizzes, discussions, assignments, H5P activities, etc.) to balance the type of tasks students do in the course (e.g., individual vs group or written vs oral).

Another way to do this would be to allow students to choose how they will demonstrate that they learned the aligned course or module objective. For example, instead of assigning a traditional written out synthesis paper, you could still ask students to synthesize materials, but instead of requiring a paper, you could allow them to choose the type of product they produce (e.g., paper, presentation, video, website). This type of agency lets students demonstrate their individual strengths.

You could also encourage students to explore topics from their unique identity perspectives. This could include inviting students to critique the current literature in your field for biases, or it could also include inviting students to respond to course readings from their own personal experiences.

2. Make assessment criteria clear from the beginning

You may also recognize this best practice from the QM rubric. Standards 3.2 and 3.3 state that “the course grading policy is stated clearly at the beginning of the course” and “specific and descriptive criteria are provided for the evaluation of learners’ work, and their connection to the course grading policy is clearly explained”, respectively. Therefore, these best practices are true from a general teaching perspective and from an inclusive teaching perspective.

To make sure that all students can succeed on a given assignment, communicate specific assessment criteria when the assignment is given. You’ll provide this information in the rubric, but you could also include a description of successful versions of the assignment, and other Transparent Assignment Design strategies. Transparent assignment design is the process of designing assignments so that the process of learning is more explicit for students. In other words, transparent assignments shed light on the assignment’s purpose, task, and criteria (Bose et al., 2020). UTA’s assignment template provides a template for getting started with this by including headings for the prompt, guidelines, and support.

3. Include a variety of different assessments

This is also present in the QM rubric; standards 3.4 and 3.5 states that “the assessments used are sequenced, varied, and suited to the level of the course” and “the course provides learners with multiple opportunities to track their learning progress with timely feedback”, respectively. When we say to include various types of assessments, we mean that in any given course, you should use more than one or two types of assessments. For example, you could include weekly quizzes and discussions, and then have one or two longer essays throughout the course.

However, you should also include diversity in the types of assessments, which have different functions. Diagnostic assessments typically come at the beginning of a course; they provide informal opportunities for you to learn what students know going into your course so that you may adjust instruction accordingly. Formative assessments promote practice and create opportunities for you to give feedback to students to guide their learning. Like diagnostic assessments, formative assessments provide you with information that can inform instruction. Summative assessments provide opportunities for formal evaluation, typically for the purposes of a grade (Marquis, 2021).

You should also incorporate a balance of low-stakes and high-stakes assessments because all students can benefit from these. Low-stakes assessments are typically more informal and formative, and they may be graded (with a very low point value) or ungraded. These are important because they give students the opportunity to practice (without the risk of negatively impacting their final grade) and receive feedback, which enhances their learning (Marquis, 2021). Examples of these could include comprehension/reading quizzes, H5P activities, and reflective assignments. Conversely, high-stakes assessments are more formal and summative and have grades that represent a significant portion of their grades. Examples of these may include final projects or papers, midterms or final exams, etc.

4. Make sure you’re assessing the learning you’re aiming for

This best practice also overlaps with the QM rubric; standard 3.1 states that “the assessments measure the achievement of the stated learning objectives”. There are two major things to keep in mind here.

First, when creating an assessment, always make sure that it relates to your materials and to your objectives.

Second, be sure that the assessment is focusing on the skills or knowledge from the course and not from something else. For example, if you’re asking students to present something, be sure the assessment is focused on things you discussed in the course and not on the student’s ability to actually present (unless of course, that’s something covered in the course). In any case, be clear about the specific learning you are aiming to see displayed will help you to better identify aspects of your assessments that you may be able to adjust. For instance, grading criteria for presentations might privilege the conceptual learning you want to see displayed over public speaking skills (Barkley & Major, 2016).

5. Provide descriptive, forward-looking feedback

Feedback is an essential component of the learning process. From a diversity and inclusivity perspective, giving students good, quality feedback is important so that students know how they’re doing in your course and what they need to do to improve. Usable, meaningful feedback doesn’t need to be labor intensive. Indeed, research shows that providing too much feedback (for instance, on written work) can be overwhelming and inhibit learning.

Even a few key observations that describe what is and is not working in an assessment can help students better self-assess. Concrete strategies for improvement also can help to ensure all students have the information they need to be successful (Watling & Ginsburg, 2018).

In your feedback, be sure to let students know what they’re doing well and what they could be doing better. Moreover, be sure you also give students the opportunity to use the feedback you provide (Brookhart, 2008). For example, will the feedback apply to future assignments as well, or will they be able to use it to revise the current assignment?

Activities (not graded or low stakes)

Activities, for the purpose of a course map, is anything the student does in the course that isn’t directly graded. For example, you might have an ungraded video quiz or an H5P activity that you want students to complete.

Activities can include activities that you mark as either complete or incomplete.

Activities always include reading and watching the materials in the “materials” column and should be noted.

Assessments (graded)

Assessments are anything that your students complete for a grade (quizzes, exams, papers, projects, discussions, etc.). So, you need to decide what kind of assessment will best test whether your students learned what the objective said they would learn. Once you have measurable verbs, it’s also important that you choose an assessment that aligns with the verb.

For example:

| Verb | Assessment |

|---|---|

| Define

Identify Recognize Categorize Classify |

Quiz |

| Describe

Explain Summarize Interpret |

Quiz/Assignment (short answer or essay questions) |

| Discuss

Defend Interpret Critique Compare Relate Contrast |

Discussion |

| Write

Evaluate Analyze Conclude Judge Cite Solve |

Written assignment/essay |

| Design

Develop Plan Create Use Illustrate |

Course project |

| Collaborate

Complete |

Group assignment |

Is it a learning activity or an assessment?

Learning activities and assessments can be thought of the same; they are anything that incorporate interaction and engage the learner with the course content. For example:

- Class discussions

- Simulation exercises

- Practice quizzes

- Tests

- Case studies

- Role-playing

- Student presentations

- Labs

For example, you may have a discussion where in order to participate in the discussion, students will first have to read two articles. The reading of the two articles would be the learning activity. The discussion post the student creates is then the assessment.

Another example is when a learning objective requires a student to apply a concept to a real-life case. The learning activity could be the student applying that concept to a case study and the assessment is how well the student did when they applied that concept to the case study.

References

Ragupathi, K. (2016). Designing Effective Online Assessments: Resource Guide.

Brooks, R., & Grady, S. D. (2022). Course design considerations for inclusion and representation. Quality Matters White Paper. https://www.qualitymatters.org/qa-resources/resource-center/articles-resources/course-design-inclusion-representation-white-paper

Crawford, Stephen (2012). Aligning Assessments with Learning Objectives. http://teachonline.asu.edu/2012/10/aligning-assessments-with-learning-objectives/.

Appert, L., Simonian Bean, C., Irvin, A., Jungels, A. M., Klaf, S., & Phillipson, M. (2017). Guide for Inclusive Teaching at Columbia. Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning. https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/inclusive-teaching-guide/download/

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., & Norman, M. K. (2010). How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. John Wiley & Sons.

Davis, B. G. (2009). Tools for Teaching. Second Edition. John Wiley & Sons.

Malamed, C. (n.d.). Why You Need To Use Storytelling For Learning. http://theelearningcoach.com/elearning2-0/why-you-need-to-use-storytelling-for-learning/.

Mills, E. (2017). Don’t Overlook the Value of Storytelling in Instructional Design. https://www.caveolearning.com/blog/dont-overlook-the-value-of-storytelling-in-instructional-design.

Pappas, C. (2014). 7 Tips To Integrate Storytelling Into Your Next eLearning Course. https://elearningindustry.com/7-tips-integrate-storytelling-next-elearning-course.

Ko, S., & Rossen, S. (2017). Teaching Online: A Practical Guide. Taylor & Francis.

Zhadko, O., & Ko, S. (2019). Best Practices in Designing Courses with Open Educational Resources. Taylor & Francis.

Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., Norman, M. K., & Ambrose, S. A. (2023). How Learning Works: Eight Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. Wiley.

Bose, D., Dalrymple, & Shadle, S. (2020). A renewed case for student success: Using transparency in assignment design when teaching remotely. Faculty Focus. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/course-design-ideas/a-renewed-case-for-student-success-using-transparency-in-assignment-design-when-teaching-remotely

Reinert Center for Transformative Teaching & Learning. (2017). Resource Guides for Assessment and Assignment Design. Saint Louis University. https://www.slu.edu/cttl/resources/inclusive-teaching.php

Marquis, T. L. (2021). Formative assessment and scaffolding online learning. New Directions for Adult & Continuing Education, 169, 51-60. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.20413

Watling, C. J., & Ginsburg, S. (2018). Assessment, feedback, and the alchemy of learning. Medical Education, 53(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13645

Barkley, E. F., & Major, C. H. (2016). Learning assessment techniques : A handbook for college faculty . Jossey-Bass.

Brookhart, S. M. (2008). How to give effective feedback to your students . Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Nestor, M. & Nestor, C. (2013, November 25). Alignment and Backward Design. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZTv2HR2ckto.