5 Quizzes

Jessica Kahlow

The digital transformation in education has revolutionized the way assessments are conducted. Online quizzes and exams have become integral components of both traditional and virtual learning environments, offering flexibility, immediacy, and a range of interactive possibilities. This chapter explores the essential elements and best practices for creating effective online assessments that accurately measure student learning and foster engagement. Online assessments serve multiple purposes:

- Evaluating Learning: They help measure students’ understanding and retention of course material.

- Providing Feedback: Instant feedback mechanisms in online quizzes can guide students in their learning journey.

- Encouraging Engagement: Interactive and diverse question types can make learning more engaging.

To Quiz or not to Quiz

Exams may not be the best fit for all courses. Exams are stressful, inequitable, logistically difficult, not empathetic, and frankly, no one likes them (Saucier et al., 2022). Quizzes may not be the best assessment fit for a course, but they could be a great activity for a course. There are a lot of fun technologies out there (e.g., Google Forms, Kahoot, H5P, Genially, Canva, and Quizlet) that provide additional functionalities for creating engaging and interactive quizzes that you could use as an interactive activity. However, be sure to be prepared to make accommodations for students facing technical issues or requiring additional support.

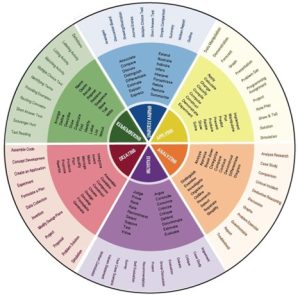

To start, are you sure a quiz is your best option? Recall Bloom’s taxonomy wheel from the page on selecting an assessment type. According to that wheel, how many levels of Bloom’s learning verbs can be assessed with a multiple-choice quiz? Right, only two learning objectives are tested with multiple-choice questions. Those types of questions are most beneficial when assessing if students can remember factual information. And yet they are the go-to assessment strategy a majority of the time. If you only use multiple choice quizzes in your course, how are you going to find out if students can apply and analyze the knowledge you have given them? As you study the wheel, you will see that to bring students up to using higher-order thinking skills, you will need to vary your assessment techniques. However, there are some strategies you can use that I’ll discuss here to get your quiz questions up to higher levels of Bloom’s taxonomy.

Sometimes you will have to use multiple choice tests because of time or grading constraints or the content covered in the course (e.g., it would probably be fine to forgo quiz assessments in an introduction to communication course, but it might be less fine to forgo quizzes in a course where you’re literally teaching future doctors how to be a doctor. In this case, you can still write your multiple choice questions to test students on levels above the knowledge level. Here is an example.

Original Question

Place the steps in order, from start to finish, for designing a course with backward alignment.

- Write measurable, action-oriented learning objectives that address the appropriate level of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

- Choose assessment methods that indicate students’ mastery of the objectives and materials.

- Choose instructional materials that help students work towards those objectives

Rewritten Question

Tyler is using the backward design method to develop his course. He has written his learning objectives for the lesson. What will he choose in his next step?

- Assessment methods

- Instructional activities

- LMS tools

- Technology resources

The question has been taken from the knowledge level to the application level. Students have to know the order of steps (knowledge level) and then apply it to a situation (application level). We are testing both with one question.

Aligning Quiz Questions

Effective quizzes and exams must align with the course’s learning outcomes. Each question should directly relate to a specific objective, ensuring that the assessment accurately measures the intended outcomes. Incorporating a mix of question types can assess different levels of cognitive skills, from basic recall to higher-order thinking:

- Multiple-Choice Questions: Good for assessing factual knowledge and comprehension.

- True/False Questions: Useful for quick checks of understanding.

- Short Answer and Essay Questions: Evaluate deeper understanding and the ability to articulate complex ideas.

- Matching and Ordering Questions: Test recognition and understanding of relationships between concepts.

- Scenario-Based Questions: Present real-life scenarios to assess application and analysis skills.

Online assessments support a variety of question types; refer to the list below for question types, descriptions, Bloom level, advantages, and disadvantages of each.

| Question Type | Description | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Choice | Multiple choice questions present a question and ask students to choose from a list of possible options/answers. Most MCQs feature one correct answer, and two to four “distractor” choices that are incorrect. Questions can take the form of incomplete sentences, statements, or complex scenarios. MCQs are most appropriate for factual, conceptual, or procedural information. Some simple rules of thumb that can make for more effective questions: | MCQs are the most versatile of the closed-ended question types. This versatility stems from the fact that the questions can contain more elaborate scenarios that require careful consideration on the part of the student. The probability of student guessing is also relatively low. | When compared to true/false and matching, multiple-choice items can be more challenging to write. They also require the creation of plausible “distractors” or incorrect answer options. As with other closed-ended questions, multiple-choice assesses recognition over recall. |

| Multiple Response | MRQs are very similar to the MCQs except that it has more than one correct answer. MRQs present a question and ask students to choose multiple options from a list of possible options/answers and usually has more than one correct answer. | MCQs are most appropriate for factual, conceptual, or procedural information | Scoring can be complicated if students don’t select all of the correct answers, which can make these questions seem more difficult than they really are. |

| Fill-in-the-blanks | Fill-in-the-blank questions are “constructed-response,” that require students to create an answer and typically one word answers. Completion questions are also similar to fill-in-the blank question types. Fill-in-the-blank questions are most appropriate for questions that require student recall over recognition. Examples include assessing the correct spelling of items or in cases when it is desirable to ensure that the students have committed the information to memory. | Fill-in-the-blank questions assess unassisted recall of information, rather than recognition. They are relatively easy to write. | FIB questions are only suitable for questions that can be answered with short responses. Additionally, because students are free to answer any way they choose, FIB questions can lead to difficulties in scoring if the question is not worded carefully. |

| True/False | True/false questions present a statement, and prompt the student to choose whether the statement is true. Students typically have a great deal of experience with this type of question. T/F questions are most appropriate for factual information and naturally dichotomous information (information with only two plausible possibilities). Dichotomous information is “either/or” in nature. | True/false questions are among the easiest to write. | True/false questions are limited in what kinds of student mastery they can assess. They have a relatively high probability of student guessing the correct answer (50%). True/false also assesses recognition of information, as opposed to recall. |

| Matching | Matching questions involve matching paired lists that require students to correctly identify, or “match” depending on the relationship between the items. These are most appropriate for assessing student understanding of related information. Examples of related items include states and capitals, terms and definitions, tools and uses, and events and dates. | Matching items can assess a large amount of information relative to multiple-choice questions. If developed carefully, the probability of guessing is low. | Matching assesses recognition rather than recall of information. |

| Essay/Short Answer | Essays and short-answer types are constructed-response questions. However, essay answers are typically much longer than those of short-answer, ranging from a few paragraphs to several pages. Most appropriate for assessments that cannot be accomplished with other question types. Because essays are the only question types that can effectively assess the highest levels of student mastery, they are the only option if the goal of testing is the assessment of synthesis and evaluation levels. | Essay questions are the only question type that can effectively assess all six levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy. They allow students to express their thoughts and opinions in writing, granting a clearer picture of the level of student understanding. Finally, as open-ended questions, they assess recall over recognition. | There are two main disadvantages to essay questions — time requirements and grading consistency. Essays are time-consuming for students to complete. Scoring can be difficult because of the variety of answers, as well as the “halo effect” (students rewarded for strong writing skills as opposed to demonstrated mastery of the content). |

Writing Good Quiz Questions

In contemporary education, multiple-choice examinations are inescapable. Yet, studies over decades confirm that many of the questions used in these tests are of dubious validity because of shoddy construction. This activity provides a stepwise guide to construct good multiple-choice questions (MCQs). Before you get started writing a question, be certain that you are testing an important concept—a “take-home” message that you really want the learners to understand and remember. Questions about minutiae are easier to write, so avoid the temptation.

What are the parts of a question?

- The stem is the part that asks the question.

- The distractors are the incorrect answer options.

- The key is the correct answer choice.

Writing The Stem

Probably, the most important single concept in writing a strong MCQ is to have a well-focused stem. That means that the main idea of the question must be found in the stem. A good way to test the quality of your stem is to cover the options and see if you can answer the question.

Examples of good, well-focused stems

- “On computed tomography (CT), what is the typical contrast enhancement pattern of a hepatic cavernous hemangioma?”

- “What pancreatic tumor most often shows radiographically evident calcification?”

Examples of poor, unfocused stems

- “Which of the following is true regarding dual-energy CT?” “Concerning ovarian carcinoma, it is correct that:”

- Such unfocused stems turn an MCQ into a group of loosely related true-false questions.

In creating your stem, use simple wording and avoid any extraneous information not needed to answer the question.

Example of a stem with extraneous information

- “Numbness of the right side of the lower lip of a 60-year-old woman with facial injury due to a motorcycle accident is most likely caused by a fractured mandible with displacement of the ________.”

Unnecessary information removed

- “With mandibular fracture, displacement of what structure is the most likely cause of lower lip numbness?”

Test takers benefit from clarity and conciseness. Be sure to avoid “negative” constructions:

- “…each of the following EXCEPT,”

- “Which of the following is NOT associated with…”

You want the test takers to stay in “find the right answer” mode.

Writing the Answer Choices

The correct answer (or key)

The most important attribute is that the choice identified as correct must be 100% incontrovertible. Ideally, you should have a manuscript citation or reference available for corroboration. In writing the correct answer, avoid nebulous terms such as “frequently,” “often,” “rarely,” or “sometimes” because they can give clues as to what the correct answer is.

The distractors

From the psychometric standpoint, having two distractors is fine, although three is more typical. These can be the most challenging part of constructing a good question because plausible distractors are difficult to write. Your distractors should be plausible and not be obvious “throw-away” options. Using plausible distractors helps ensure the learner really knows the correct answer and isn’t just deducing the right answer. For similar reasons, “all of the above” and “none of the above” are frowned upon. Each question should test a single concept.

Avoiding clues in the answer options

Examples of constructions that draw attention to one of the choices:

-

- One option is significantly longer or shorter than the others (longer answers are usually correct).

- Definite modifiers such as “always” or “never” (clues that an answer is false)

- A choice “highlighted” by capitalization, quotation marks, or parentheses

- A choice whose grammar doesn’t agree with the stem

- And don’t include two options that form a mutually exclusive pair, such as “Worse when the patient inhales” and “Worse when the patient exhales” because frequently, one of the pair is the correct answer, improving the guessing odds for the test taker.

Purpose of Bloom’s Taxonomy

Bloom’s Taxonomy provides a framework for creating well-structured quiz questions that assess different levels of cognitive skills. When writing Multiple Choice Questions (MCQs) or Multiple Response Questions (MRQs) (where students can select more than one correct answer), it’s important to align each question with the appropriate cognitive level.

While MCQs and MRQs are typically associated with lower-level thinking, such as recall and comprehension, but with thoughtful question crafting, they can reach the Evaluate and Create levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Questions by Bloom’s Level

Remember

The remembering level forms the base of Bloom’s Taxonomy pyramid. Because it is the lowest complexity, many of the verbs in this section are in the form of questions. You can use this level of questioning to ensure students can recall specific information from the lesson.

Best Practices

- Keep the questions straightforward.

- Use simple, clear language.

- Ensure distractors (incorrect answers) are plausible to avoid guesswork.

Examples

- Define mercantilism.

- Name the inventor of the telephone.

- List the 13 original colonies .

- Label the capitals on this map of the United States.

- Locate the glossary in your textbook.

- Match the following inventors with their inventions.

- Select the correct author of “War and Peace” from the following list.

Understand

At the understanding level, you want students to show that they can go beyond basic recall by understanding what the facts mean. The questions at this level should allow you to see if your students understand the main idea and are able to interpret or summarize the ideas in their own words.

Best Practices

- Focus on questions that ask students to explain or classify concepts.

- Use distractors that test common misconceptions.

- Ensure correct answers involve interpretation, not mere recall.

Examples

- Explain the law of inertia using an example from an amusement park.

- Outline the main arguments for and against year-round education.

- Discuss what it means to use context to determine the meaning of a word.

- Translate this passage into English.

- Describe what is happening in this Civil War picture.

- Identify the correct method for disposing of recyclable trash.

- Which statements support implementing school uniforms?

Apply

At the applying level, students must show that they can apply the information they have learned. Students can demonstrate their grasp of the material at this level by solving problems and creating projects.

Best Practices

- Use real-world scenarios to assess how students can apply their learning.

- Ensure distractors represent common mistakes or incorrect applications of knowledge.

- Provide sufficient context to make the scenario clear.

Examples

- Using the information you have learned about mixed numbers, solve the following questions.

- Use Newton’s Laws of Motion to explain how a model rocket works.

- Using the information you have learned about aerodynamics, construct a paper airplane that minimizes drag.

- Create and perform a skit that dramatizes an event from the civil rights era.

- Demonstrate how changing the location of the fulcrum affects a tabletop lever.

- Classify each observed mineral based on the criteria learned in class.

- Apply the rule of 70 to determine how quickly $1,000 would double if earning 5 percent interest.

Analyze

Analyze questions need to assess the ability to break information into components and understand their relationships. These questions often require students to examine data, compare different ideas, or determine relationships.

Best Practices

- Ask students to identify relationships, causes, or underlying principles.

- Provide scenarios that require critical thinking and comparison.

- Use distractors that represent incomplete or incorrect analysis.

Examples

- Which of the following best explains the relationship between supply and demand in a competitive market?

- Which of the following factors likely contributed to the economic recession of 2008?

Evaluate

Evaluate questions ask students to assess the ability to make judgments based on criteria and standards. These questions often involve decision-making, prioritizing options, or determining the best course of action.

Best Practices

- Focus on real-life dilemmas or problems that require students to make informed judgments.

- Ensure distractors represent common but flawed evaluations.

- Make the criteria for evaluation clear, even if implicit.

Examples

- Which of the following actions would be the most ethical response in a case of workplace discrimination?

- Which of the following policies would be most effective in reducing unemployment?

Create

Create questions typically are not best suited for a quiz, but it could be done through essay questions. Asking students to “create” something in a quiz can be challenging, especially when quizzes are often designed for objective assessments. While it’s possible to integrate creation-focused tasks into a quiz by using innovative question types that encourage students to apply higher-order thinking, these types of assessments are typically better suited as assignments.

Best Practices

- Clarity and Guidelines: Since creation tasks are more subjective, ensure that questions are clear and provide specific expectations for what students should create.

- Rubrics: Use detailed rubrics that outline criteria like originality, depth of thought, relevance, and adherence to course content. Rubrics will help in grading creative assignments more objectively.

- Scaffolded Support: Consider scaffolding the creation process. For example, if the final product is complex, you can ask students to submit drafts or preliminary ideas in earlier quizzes.

Examples

- Ask students to create a thesis statement based on provided data or readings.

- Provide a real-world problem and ask students to design a solution or response

Overall Tips for Writing Good Quiz/Exam Questions

To write effective multiple-choice and multiple-response questions, follow these guidelines to ensure clarity, fairness, and alignment with learning outcomes.

- Questions should be clear, concise, and free of ambiguity to prevent misinterpretation.

- Distractors (incorrect answer options) should be plausible so that students can’t easily eliminate them, and terms like “always” or “never” should be avoided to prevent obvious answers.

- Options like “all of the above” and “none of the above” should be used sparingly.

- Ensure that questions are culturally neutral, accessible to all students (including those with disabilities), and free of bias.

- Each question should be directly related to a learning outcome and cover a single concept, with simple and precise language. Incorporating a variety of question difficulties will help differentiate levels of student understanding.

When designing a quiz or exam,

- Determine its purpose: formative (to provide ongoing feedback) or summative (for final evaluation).

- Choose question types that align with your learning objectives and cover a range of cognitive levels.

- Provide timely feedback so that students can learn from their mistakes.

- Before releasing the assessment, test it yourself or with a colleague to ensure clarity, technical functionality, and appropriate timing.

- After the assessment, analyze the results to spot trends or issues that can highlight areas where students struggled, potentially indicating gaps in instruction.

To ensure your questions are focused, make sure the main idea is clearly stated in the question stem and use simple wording. All answer options should be plausible, avoiding complex or tricky language. Remember, bad questions are easier to write than good ones. While writing effective questions can be challenging, these straightforward principles will help create assessments that are clear, fair, and valid, providing better learning opportunities for your students.

Security and Academic Integrity

There are also several things you can do to maintain the integrity of online assessments:

- Randomize Questions: Use question pools and randomization to create unique quizzes for each student.

- Timed Assessments: Limit the time available to complete the quiz to reduce the likelihood of cheating.

- Proctoring Tools: Use online proctoring services if necessary to monitor exams. Respondus Monitor helps maintain academic integrity in high-stakes online exams by providing secure proctoring environments.

Conclusion

Creating effective online quizzes and exams requires careful planning, a deep understanding of assessment principles, and the strategic use of technology. By aligning assessments with learning objectives, diversifying question types, ensuring clarity and fairness, and leveraging digital tools, educators can design assessments that not only measure student learning accurately but also enhance the overall learning experience.

References

Brame, C. J. (2013). Writing good multiple-choice test questions. https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/writing-good-multiple-choice-test-questions/

Moniquemuro. (2019). How to create a quiz in your online course (that doesn’t suck). ProofMango. https://proofmango.com/create-a-quiz-in-online-course/

Saucier, D. A., Renken, N. D., & Schiffer, A. A. (2022). Five reasons to stop giving exams in class. Faculty Focus. https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/educational-assessment/five-reasons-to-stop-giving-exams-in-class/

Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. (n.d.). Giving exams online: Strategies and tools. https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/online-exams/

Ye, H. (2019). Best practices for online quizzes. FOCUS Center for Teaching and Learning, Cedarville University. https://ctl.cedarville.edu/wp/best-practices-for-online-quizzes/