11 Issues for Infant and Toddler Feeding at Disaster Mass Care Sites: Paradigm Shifts for Strategic and Operational Planning

Michael Prasad, MA, CEM® and Jennifer Russell, MSN, RN, IBCLC, NHDP-BC, CHEP

Authors

Michael Prasad, The Center for Emergency Management Intelligence Research

Jennifer Hope Russell

Keywords

pediatric feeding; mass care; access; infant/toddler; breastfeeding support; equity

Abstract

There are currently disparities in the support of family choices for infant/toddler feeding by families during disasters in the United States. The current U.S. federal/national model only supports commercial infant formula as an immediate substitute in the event of issues or challenges with breastfeeding/chestfeeding (FEMA 2022). Most U.S. states, local governments, tribal nations and territories do not have complete solutions to support the preexisting and pre-disaster family-led choices for feeding, at shelters and other disaster fixed feeding sites. There are opportunities to apply global standards and best practices, in the United States and other countries, for more equitable and healthier results via a top-down and bottom-up grassroots change-management workflow.

This chapter is an academic detailing of the pracademic (i.e., both practitioner and academic) journey, first introduced to Emergency Management professionals and others in 2023 (Prasad and Russell 2023). The authors provided tactics and methods which could be used by anyone, to further solutions in their own jurisdictions.

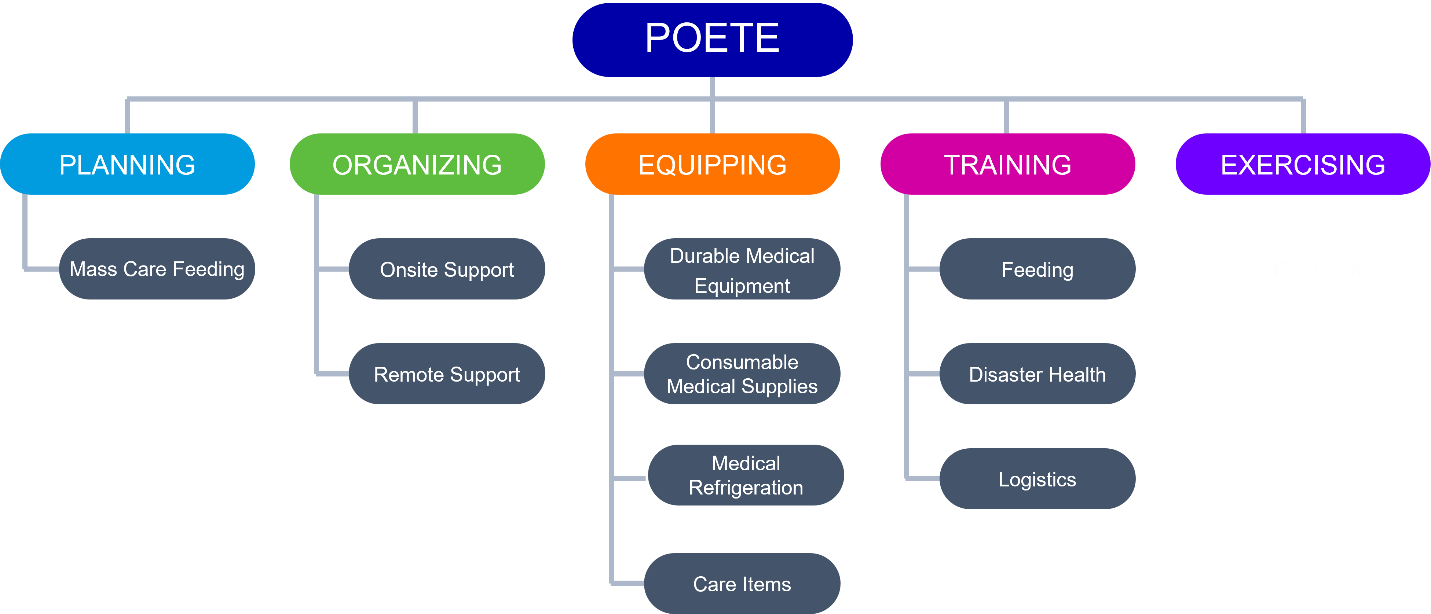

The authors have continued their pracademic research and advocacy, beyond just documenting the real-world problem in that prior article, towards the goal of deliberative planning changes needed in policies and procedures detailed in this chapter. One goal of this chapter is to effectively eliminate the lack of awareness of this pediatric feeding problem during disasters, and potential solutions. Another goal is to describe a novel top-down and bottom-up grassroots multi-pronged advocacy approach, coupled with the academic process of research and publishing, to effect a paradigm shift in strategic and operational planning. Utilizing the Emergency Management practitioner methodology of the POETE process (FEMA 2018) for continuous improvement problem-solving, the authors have separately and jointly embarked on this journey for positive change on this concern, which can have constructive outcomes on this and other disaster equity issues, throughout the United States and internationally.

Introduction

This chapter is designed to describe the processes and advocacy that the authors have employed so far, from a pracademic (i.e., both practitioner and academic) perspective. It includes the research and advocacy work towards urgently solving the specific emergency management problem of the lack of family choice for infant/toddler feeding support at disaster sites, such as shelters. This chapter also includes the advocacy work to help facilitate policy changes to support all levels of jurisdictions in their complete disaster cycle (before, during, and after) work towards that problem over the long-term. While this chapter is focused on the work being done in the United States, the problem is global (Hwang, Iellamo and Ververs 2021) – and the author’s solutions can be applied in every country. Per WHO and UNICEF standards (World Health Organization 2021), support for breastfeeding during disasters needs to be, and can be supported globally.

Breastfeeding is universally recognized for its protective benefits for the mother, baby, family, and community. Proper nutritional support for infants and toddlers becomes even more critical (Grubesic and Durbin 2022) during disasters (US Centers for Disease Control 2023) in any country. Breastfeeding/chestfeeding offers cost-effective (Gribble, Peterson and Brown 2019) and tailored nutrition for infants and toddlers (IFE Core Group 2017), and providing immune support and sufficient caloric intake (World Health Organization 2023). Current U.S. Federal disaster response and recovery guidance (FEMA 2022) only supports a switch to commercial infant formula for any infant/toddler who may have challenges with breastfeeding. Globally, this has been criticized as being exploitative (World Health Organization 2023).

Awareness of the changes needed at all governmental levels (e.g., to policies, procedures, planning, etc.) has now been introduced (Prasad and Russell 2023). This includes the support for additional durable medical equipment, consumable medical supplies, and personal assistance services [1] to the local general population shelter’s mass care feeding missions. Most of these elements can be shared, borrowed, donated, etc.; and the availability of lactation counseling support should be culturally and faith sensitive, for the families impacted. Much of the problem-solving for any breastfeeding issues is nature-based (Hoffman and Henly-Shepard 2023) and cost-effective (Hunt, et al. 2021). Families must be supported at the general population shelter serving people with disabilities and access/functional needs (FEMA 2023), so support for infant/toddler feeding aspects should be included at those sites. These changes must be made at the state, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) levels and financially supported at the federal level, to help protect the health of infants and toddlers adversely impacted by disasters.

This chapter will provide a window into Prasad’s use of the Planning, Organizing, Equipping, Training, and Exercising (POETE) (FEMA 2018) process-driven advocacy, research, and corrective actions, towards making these changes throughout the United States. The authors believe that top-down and bottom-up grassroots-led changes to U.S. Federally Declared Disaster Public Assistance [2] Emergency Work – Category B: Emergency Protective Measures (FEMA 2020) policies, to specifically include support for breastfeeding/chestfeeding elements, will help effect top-down changes to the SLTTs in the U.S. In advance of those needed policy amendments, the foundation for SLTT support of family choices for infant/toddler feeding during disasters, will be introduced in this chapter.

TEXT BOX 1: The Nexus Point for two Pracademics

During his prior independent practitioner research, Prasad recognized this pediatric disaster feeding concern was a “Pink Slice”/Johari Window problem – something emergency managers ‘did not know they did not know’ (Barton Dunant 2018).

The ‘Johari’ window model is a convenient method used to achieve this task of understanding and enhancing communication between the members in a group. American psychologists Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham developed this model in 1955. The idea was derived as the upshot of the group dynamics in University of California and was later improved by Joseph Luft. The name ‘Johari’ came from joining their first two names. This model is also denoted as feedback/disclosure model of self-awareness. (Communication Theory N.D.)

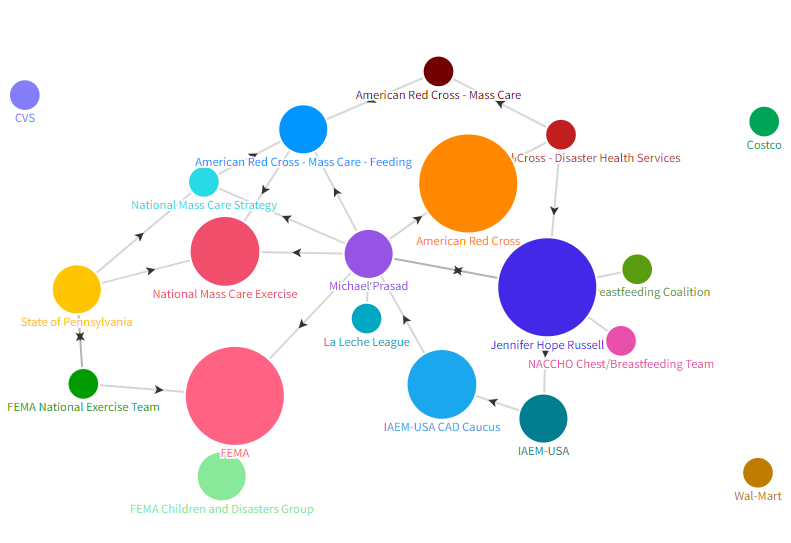

Prasad’s past practitioner research provided a possible non-legislative pathway for change, even though it was not going to be implemented via a current formal academic advocacy/change model or theory. As noted by Stachowiak (Stachowiak 2013), the “Power Politics theory” from Mills (Mills 1956), may come into play, for this problem statement at some point in the authors’ pracademic advocacy work. Mills believed that only the top leaders in politics, corporations, and the military had influence on society, and not just any ordinary citizen. The authors have focused their own advocacy efforts on individuals and groups who could be considered ‘Emergency Management elites’ (decision-makers, internal influencers, etc.). As of publishing this chapter, this has included:

- Limiting advocacy efforts to focused groups (and not the general public),

- Identifying individuals and advocacy organizations who have an influence for this specific problem statement – and the policy changes needed in the United States to fix it – and developing/furthering relationships with them, and

- Using the POETE process to provide a strategy of relationship development, communications, collaborations, and continuous improvement with those who have influence (Stachowiak, 2013).

However, the question of whether the authors themselves will be considered by the influencers as credible partners (one of the key factors for the Power Politics theory), remains to be seen. Prasad’s position as chair of the IAEM-USA CAD, familiarity with key staff at FEMA, and knowledge of the organizational construct of the Disaster Cycle Services and other leaders and groups of the American Red Cross’ National Headquarters, may have a positive influence for this problem statement. Meanwhile, Russell has been acknowledged as a strong advocate for inclusive, diverse, equitable and accessible breastfeeding support, in the pediatric healthcare field. Both have published academically, prior to this chapter.[3]

TEXT BOX 2: Disaster Pediatric Feeding Concerns Defined

The authors collaborated to further describe the problem statement to the pracademic world, through an article in the Domestic Preparedness Journal (May 10, 2023), which was published by the Texas Division of Emergency Management. This article effectively first introduced the problem statement to Emergency Management practitioners. It contained tactics and methods which could be used by anyone, to further solutions in their own jurisdiction. The authors have also continued both their pracademic research and pracademic advocacy, beyond just documenting the problem in the article and effectively eliminating the Pink Slice of lack of awareness of a problem and its potential solutions. Please see Appendix A for a full reprint of that article.

Literature Review

The Literature Review for this chapter will be comprised of two parts. First, the review of the academic literature to justify the need for breastfeeding support in disaster shelters will be mentioned. Second, the review of literature associated with making changes to governmental disaster policies and procedures at the federal, state, and local levels in the United States and other countries will be covered. These two components of the literature review are aligned to the two-fold purpose of this chapter: justifying the paradigm shift needed globally to fully support a family’s choice in how their infants and toddlers are fed, during a disaster; and proposing a novel approach to making policy and procedural changes in Emergency Management.

The Strong Academic Case for Breastfeeding Support During Disasters

The Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding (World Health Organization 2021) asserts the critical importance of an environment that protects, promotes, and supports breastfeeding during challenging circumstances such as natural or human-induced emergencies. These safeguards described by the World Health Organization include: (a) maternal-child policies and actions that provide lactation support; (b) supervision and coordination of the distribution of human-milk substitutes and complementary foods; (c) provision of trained lactation support; (d) lactation training for healthcare professionals; e) development of community peer-to-peer support networks; and (f) following guidelines in the World Health Organization International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes.[4]

Further, the “Infant and Young Child Feeding in Emergencies: Operational Guidance for Emergency Relief Staff and Programme Managers” (Emergency Nutrition Network (ENN) 2017) recommends that response plans include a validated early needs assessment, monitoring, or evaluation tool to assess breastfeeding mothers in any disasters. Shelter support staff for client care, feeding, health, etc. need to anticipate potential problems for anyone’s feeding needs, especially infants and toddlers.

However, existing literature highlights the significant challenges associated with infant and toddler feeding during disasters. These challenges include poorly targeted disaster assistance (Callaghan, et al. 2007); (DeYoung, Suji and Southall 2018); (DeYoung, et al. 2018); (Gribble, Peterson and Brown 2019); (Quinn, et al. 2008); (Santaballa Mora 2018); (Scott, et al. 2022), poor access to lactation supplies and support especially access to clean water, refrigeration, sanitization capabilities; and the uncoordinated and unsolicited donations of commercial infant formula or breastmilk substitutes (Fuentealba, Verrest and Gupta 2020); (Gribble, Peterson and Brown 2019); (Gribble and Palmquist 2022). The lack of adequate disaster plans,[5] and barriers to implementing the plans result in early and unplanned weaning from breastfeeding (Grubesic and Durbin 2022); (Hirani 2022).

The Lack of Academic Research on Disaster Policy Changes

Research on disasters from a sociology academic view has been the cornerstone of academic review for the field of emergency management for decades (Drabek 1984; Quarantelli 1995), and certainly disaster public policy changes through political groups has its own academic literature (Olson, Olson and Gawronski 1998). But there exists a dearth of academic literature connecting the top-down and bottom-up grassroots advocacy for protective and preventative changes in disaster or emergency management with the policies and practices of governments and non-governmental organizations supporting governmental disaster operations. For this specific problem statement, actual morbidity and mortality need not occur to require changes in policies and practices in the United States. Unfortunately, this cycle of adverse health and safety impacts and then legislative fixes, has been the norm (J. Catalino 2015). The authors are not only researching the changes needed, but actively participating in the process to effect these changes, equitably through ‘Cultural Humility’ (Yeager and Bauer-Wu 2013). This is one of the challenges and benefits of being a pracademic researcher. There is no plausible deniability when pracademics learn what needs to be fixed, how to resolve problems, and who can provide those solutions. Pracademics also have the science of “why” behind them, from multiple advocacy positions: in the authors’ case, pediatric and maternal health, social sciences, even logistics as a science (Delfmann, et al. 2010). The authors themselves are currently creating literature[6] and reference material[7] for both practitioners and academics. This book chapter is part of that process. It will also reference U.S. federal government policies [8] for declared disaster responses, along with other federal-level literature (from the U.S. and other countries (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015) covering the U.S. based National Essential Functions,[9] Emergency Support Functions, [10] Recovery Support Functions [11] the Community Lifelines,[12] and other applicable national policies and guidance for this issue. While each nation will be tasked with solving this issue within their jurisdiction, they can all learn from best practices performed globally.

There is limited academic literature and research into how changes – beyond those from internal and political sources – are made to U.S. governmental disaster-specific policies and procedures at the federal, state, and local levels, in any country. Searches were performed at the National Emergency Training Center’s Library, Searches were conducted on Pro-Quest, Google Scholar, and other academic search engines, as well. Based on their review, there is literature on making changes and organizational change management via diverse groups (Stachowiak 2013)/civic engagement (Cooper 2007), as well as the advocacy-only (and not legal requirements) for collaboration between governmental and non-governmental organizations (Kapucu 2008).

There are academic research centers which provide direct input to governments and may even be the impetus for long-term policy changes. Groups such as Rand, the Disaster Research Center at the University of Delaware, the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University, and the Natural Hazards Center at the University of Colorado are organized to do this research work, typically focused on natural or human-made hazards and focusing events (Birkland 1998) or incidents of scale (Prasad 2024). However, for this problem statement the authors are disaster-agnostic and are not affiliated with any of those institutions. They did not receive any funding to conduct this pracademic work, and do not believe the speed-to-scale (Cutter and Derakhshan 2019) timing for the current pathways for change management is appropriate for a pediatric feeding concern. Piecemeal solutioning implemented now – in advance of slower and methodical policy and doctrinal changes at any organization – must be made. In researching this problem statement, the authors quickly found disconnects (General Accounting Office 2017) between U.S. federal government groups (FEMA vs. HHS, for example), as to adherence and compliance with changes in one group’s policies and procedures, based on the recommendations of the other. The response failures during the COVID-19 pandemic certainly highlighted the issues of who oversees what, when it comes to federal disaster support to SLTTs (GovStar n.d.).

The authors believe that it is highly plausible that the effective and needed changes to current policies and procedures described in this chapter, can be cost-effectively put into practice now by local governments and their partners, without requiring bureaucratic changes in laws or regulations. People – especially children – do not need to suffer health consequences for effective and equitable changes to be made. One example of where this was not the case – and unfortunately people had to perish, before changes were made to disaster policies and procedures – was the U.S. implementation of the Pets Evacuation and Transportation Standards Act of 2006 (PETS Act) (Mike, Mike and Lee 2011), and the Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act of 2006 (PKEMRA)[13] laws. To this day, there are many local jurisdictions – and even U.S. Federal interagency coordination groups (U.S. Government Accountability Office 2016) – who have not fully implemented these two current U.S. disaster laws to provide support – including preparedness communications – for both people and their pets (J. Catalino 2015).

Another example of where the actual implementation of disaster policies and procedures does not fully align and adhere to laws, is the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)[14] and its lack of implementation in specific jurisdictions, during disasters. Even though there has been a law on the books for nearly 50 years, several local jurisdictions blatantly flout this law – and harm people, during disasters (Weibgen 2015). Breastfeeding support is not covered by the ADA. Again, the authors believe that through collaborative, top-down and bottom-up grassroots change, paradigm shifts in whole-of-government/whole-community acceptance and implementation of policy and procedural changes – such as the shift towards shelter operators supporting a family’s own choice for infant/toddler feeding modalities – is possible without changing laws and regulations.

TEXT BOX 3: Deliberative Planning

There is literature on the deliberative planning process, including pieces on applicable planning theories for urban planning (Whittemore 2021) which has relevant theories for changes to emergency management policies and procedures (rational comprehensive, incremental, transactive, communicative, advocacy, equity, radical management, and humanist intellectual models). FEMA’s Emergency Management Institute now has a Planning Practitioner Program, which can help train individuals at any jurisdiction to further mitigate losses and improve outcomes from hazards, threats, and risks. Prasad utilized this training to refine this chapter, and the top-down bottom-up grassroots approach for this problem statement is his capstone project for this FEMA course series.

Methodology

As noted above, the authors approached this pracademic work in this chapter through their prior experience and training. Methodologies used were two-fold:

- A sociology-oriented Narrative (Franzosi 1998) methodology – storytelling (Jerolleman 2021) (Freitag, et al. 2020) from both the future collection, as well as the analysis of the narratives from disaster-impacted families on their full-cycle journey. This work will be synergizing institutional decision-making groups and community actors/networks (de Vries, et al. 2020), and include the emotional recovery of both families and communities (Kargillis, Kako and Gillham 2014). Russell is incorporating this methodology into her doctoral dissertation.

- A Radical Management (Denning 2010) methodology – specifically the narratives from the authors themselves, reporting their practitioner work for change advocacy. This topic for the chapter is a case study in progress itself – the authors are conducting a novel approach – one aligned to many types of change methodologies, but not specifically driven by any – towards emergency management problem-solving. The author’s proposed methods are radical because they are novel for Emergency Management, at a minimum. The authors are also using an agile project management process (POETE: Planning, Organizing, Equipping, Training, and Exercising) as a top-down and bottom-up grassroots change-management flow (approach) to effect changes for the types of support provided, to ultimately benefit infant and toddler feeding at disaster mass care sites. This will be a continuous improvement process – one which will never be fully completed – and which, at the time of publishing this book, is still a work-in-progress. While the work to effect the change is aligned to the POETE process, the multiple steps to get to that process and the practitioner engagements, so far have categorically utilized a Radical Management methodology (Peters and Waterman 1982), one found more in corporate or business models of management. This is also because neither of the authors are in positions of authority to effect these changes themselves. The authors must rely on independent ‘meta-leadership’ (Marcus, Dorn and Henderson 2006) to get others to change the following:

- Governmental Shelter Operators. Including government-sponsored disaster feeding and health services,

- NGO Partners, who support the government’s operations of shelters, also through both disaster feeding and health services, and

- Operational Logistics, Finance/Administration, Planning, and other aspects of the full cycle of before, during, and after incidents of scale, requiring feeding support for families.

The authors are also coalescing external non-disaster supporters and disaster partners in support of this initiative for change. One example is the collaborations with the U.S. Breastfeeding Committee (USBC)[15] for their advocacy work at the U.S. Federal policies, programs, and initiatives level. The USBC was already tracking Federal and SLTT initiatives for “Infant & Young Child Feding in Emergencies (IYCF-E),” and the authors worked with them to refine/align that to their problem statement specifics. Another is working with local U.S. Public Health officials, and their tactical teams of volunteers (the Medical Reserve Corps or MRCs). MRCs can be cross-trained to support lactation counseling and other family choices for infant/toddler feeding – and therefore be embedded into disaster shelter operations.

Findings

Emergency Management – across all nations globally – can implement these strategic and operational planning solutions to support the changes to mass care feeding plans, staffing, equipment and logistics needed, training, and exercising in their own jurisdiction. The questions of funding, logistical support, training, etc. will need to be tactically resolved locally. The solutions for this specific problem statement (infant/toddler feeding support, based on pre-determined family choices) are aligned to inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility – and may be applicable for change management at the state, local, tribal, territorial, and even federal level, as top-down and bottom-up grassroots advocacy rather than top-down policy changes made through legislation only.

The Use of the POETE Process, Beyond THIRA/SPR

While the POETE process is familiar to Emergency Managers at the State/Territorial/Tribal level for their annual Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment/Stakeholder Preparedness Review (THIRA/SPR),[16] it is not currently widely utilized for general Emergency Management project management or problem solving.

Still, it is a known process, which can be aligned with S.M.A.R.T. goals which are specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and time-bound (Doran 1981). Other aspects of FEMA’s training (Continuity and Deliberative Planning) also use the POETE process. Reading Appendix A will provide further detail on the elements of the POETE process, and Figure 1 summarizes the tactical aspects of this chapter’s problem statement.

Enhancing the “P” – Planning/Plans

The authors quickly surmised that they would be breaking new ground on the pathways for change. Still, utilizing an established problem-solving methodology in Emergency Management must be acceptable to Emergency Managers. So, while the concept of a third-party advocate (rather than a supervisor, new legal requirements, etc. ordering change management) is novel, using the POETE process, as previously noted, is not. Planning, plans, and planners are all commonplace in Emergency Management; and planners look forward to continuously improving their plans. Solving for this problem statement at the local level, using the POETE process templated by the authors and others, will also add to the advocacy for change at the U.S. Federal Level. Changes to the Guidance on Planning for Integration of Functional Needs Support Services in General Population Shelters (FNSS),[17] the Commonly Used Sheltering Items Catalog (CUSI)[18] eligible emergency protective measures (Public Assistance/Category B)[19] for SLTT reimbursement during declared emergencies/disasters, and more are all needed. This overall problem statement will not be resolved with only Recovery phase support; it must be full cycle. SLTTs must be more prepared and ready to support the Response phase needs for feeding everyone. It should be noted that the author’s advocacy thus far has resulted in adding “Breastfeeding support and equipment” under the Critical Needs Assessment section for Individual Assistance,[20] as of August 16, 2023. However, that U.S. Federal financial assistance is delayed by weeks – if not longer – and only applicable to federally declared disasters, and those where the state/territory/tribal nation has requested and been approved for Individual Assistance.

Planning by an SLTT to develop/enhance their own mass care feeding plans to better support alternatives to formula-only feeding as the sole fallback for any challenges with infant/toddler feeding at disaster sites, can be aligned with the POETE process the authors took towards solving this problem in the United States. As noted previously, this work needs to occur before the disaster happens. Awareness in the public about increasing health support for nursing mothers, milk-banking, lactation counseling, and other protective and preventative elements can be established in any jurisdiction beforehand. Prasad has had deliberative planning training – including the use of POETE – and education from both FEMA[21] and the American Red Cross.[22] Features of that training – and his past experiences in policy/procedural changes at the U.S. national level[23] – guided the design of the planning for the practical solutions to this problem statement. One example is the use of a networking diagram to develop the planning team. Figure 2 shows the networking diagram the authors have started to develop, as of publication:

“O” – Organization/Staffing Roles

In research conducted with the Disaster Health Services (DHS) leadership at the American Red Cross, they indicated the support for nursing mothers (and families who choose to feed their infants/toddlers with human milk) cannot fall to shelter-based DHS staff alone. They utilize the CMIST Framework[24] Communication, Maintaining Health, Independence, Support & Safety, and Transportation – to help proactive problem-solving, but disaster health professionals in the field have too many other responsibilities to help manage and support this pediatric feeding aspect of Activities of Daily Living (ADL). Research in Australia indicates that familiar and informal people who care[25] for others with disabilities are more adversely impacted by disasters (Crawford, et al. 2023). Additional shelter staff – especially registration and feeding staff – need awareness training in the same way they need disabilities, access and functional needs (DAFN) awareness training. There is also a potential need for additional trained staff onsite for lactation counseling and/or remote support via telephone for this type of counseling (via a state or national support service) for anyone who needs it.

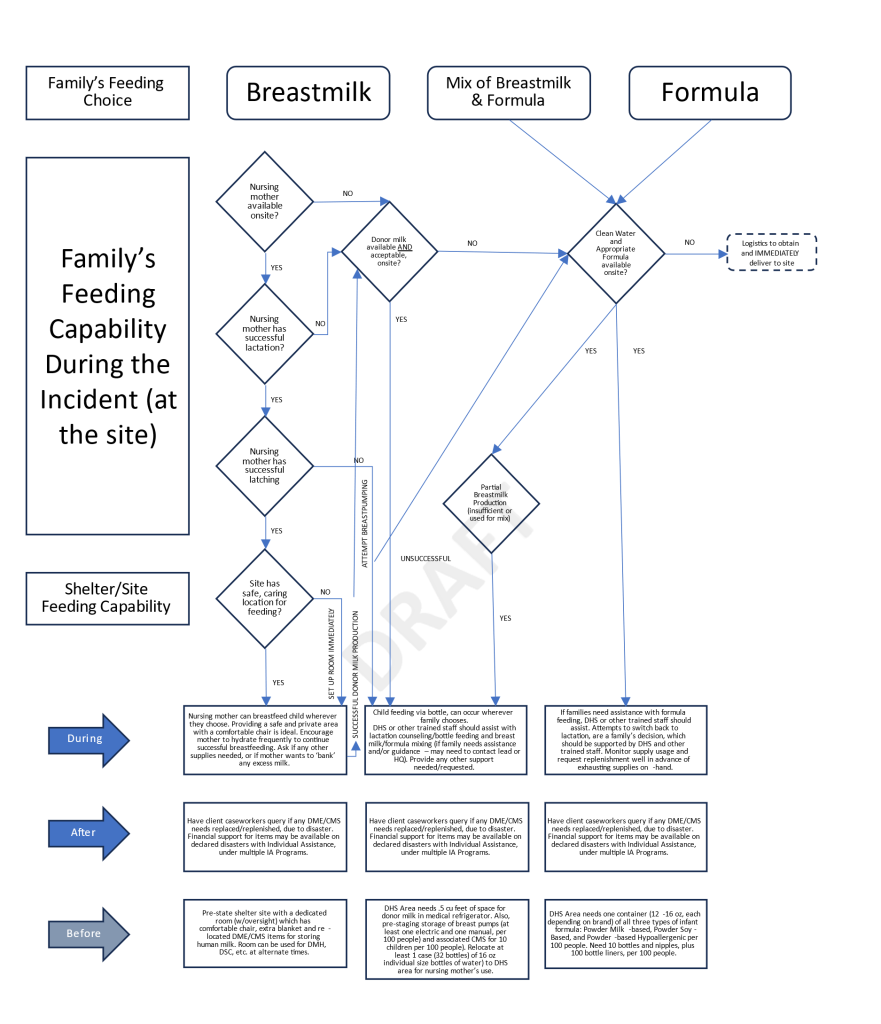

“E” – Equipment/Logistics

The heart of tactical solutions to the problem statement can be found in the equipment and logistics, especially when you include trained staff in the mix. Most jurisdictions lack enough pre-staged Durable Medical Equipment (DME) such as breast pumps and medical refrigerators, the pre-staged Consumable Medical Supplies (CMS), and the Personal Assistance Services (PAS) to fully support any challenges with breastfeeding infants/toddlers at fixed feeding/shelter sites. The planning and training for all these logistical elements must assume a worst-case scenario: it all must be on-hand/available/not expired before the first family arrives at the site, in the event the roads/routes to the site become blocked or impassable or there are other “last mile” delivery challenges (Pahwa and Jaller 2023). This is also the case for commercial formula (Jung, Widmar and Ellison 2023), as well. The consequence management planning as diagrammed in Figure 3, should be part of any Mass Care Feeding plan for everyone, not just infants/toddlers.

Logistics concerns/supply-chain management/integrity/security, timing, maintenance, cost, etc. are also concerns – again, as it should for any mass care logistical item. Questions about a jurisdiction’s ability to support on-site vs. remote PAS (lactation counseling) – and as importantly who will pay for it (insurance/Medicaid coverage?) – will require in-depth planning, organizing, training, and exercising. Disaster equipment costs in the U.S. are not necessarily a factor in Emergency Management decision-making, especially when FEMA moves the cost for these life-saving expenditures to be fully reimbursable to the State, Territory or Tribal Nation on declared incidents, per Public Assistance Category B, emergency protective measures. This is the case for a shelter cot or even a medical refrigerator now, for example – but not a breast pump or lactation counseling services.

Also, the operation’s Logistics section needs to add these physical items (DME, CMS) to the list of pre-staged temperature-sensitive equipment to be delivered to shelters and fixed feeding sites directly. Some items may not withstand temperature swings of trailer storage as cots or blankets can, for example. These logistical elements – including trained staff to support PAS will need to be delivered via transportation before the shelter opens. Obtaining additional supplies, staffing and equipment during shelter operations for replenishment, will need to be planned for as well.

“T” – Training/Education

There are training and educational information and material on the disaster feeding needs for infants and toddlers from other agencies (Administration for Children and Families (ACF) 2020) and departments (US Centers for Disease Control 2023) at the U.S. Federal Level. U.S. National advocacy groups have also provided guidance on breastfeeding during disasters. (American Academy of Pediatrics 2020). There is also training and education information and material available at the global level from the World Health Organization,[26] UNICEF,[27] and the World Health Organization.[28]

The authors are also adding to the depth of training materials and education on this concern, through material being produced in support of exercises and the POETE process. For example, a decision support tree on how shelter staff can more fully support families with their own choices for infant/toddler feeding, can be found in Figure 3. Policy makers, emergency managers, shelter operators, medical and public health professionals, and even the general public themselves should avail themselves of this training knowledge, as well as have a better awareness of their own local jurisdiction’s capacity to support infant and toddler feeding, during disasters.

“E” – Exercises/Evaluations

On the “E” side, the authors are building exercise material for the NMCS website, too. They have built an exercise planner’s guide, held three “Build-a-TTX” workshops (one each for “before, during, and after”) where whole-of-community partners were invited to collaborate, participate, and provide feedback. The authors built an overall exercise plan and four table-top exercise templates. They also participated as trusted agents for the 2024 National Mass Care Exercise (NMCE) in Pennsylvania (Keystone 6)[29] and provided their exercise planning team with a pre-exercise problem statement awareness online seminar, injects for their Master Scenario Exercise List (MSEL), and material for Exercise Evaluation Guides. The results from this large-scale exercise, on these targeted aspects for mass care pediatric feeding concerns will be shared with the authors. Those results will be included in a future article, and hopefully eventually posted to the NMCS website.[30] In the interim, all the above items can be found on this website: https://bartondunant.com/pediatric-feeding.[31]

TEXT BOX 4: The National Mass Care Strategy (NMCS) Website

https://nationalmasscarestrategy.org/

“The National Mass Care Strategy provides a unified approach to the delivery of mass care services by establishing common goals, fostering inclusive collaborative planning and identifying resource needs to build the national mass care capacity engaging the whole community including under-served and vulnerable populations.” (National Mass Care Strategy n.d.)

The site is independent of government, maintained by the American Red Cross, but contains ‘best practices’ for all things Mass Care. It is originally driven based off the 2010 Memorandum of Agreement between FEMA and the Red Cross, renewed in 2020.

As part of a full-cycle support of Emergency Support Function #6 – Mass Care, by both the Red Cross and the National VOAD, the NMCS website is tangible evidence of the commitment of both the Federal Government and leading national-level non-governmental/non-profit agencies active in disaster, to supporting the U.S. public for the four major components of mass care: feeding, sheltering, distribution of emergency supplies and family reunification. The NMCS site also has subject-matter-expertise information on

- Mass Evacuee Support,

- Household Pets, Service Animals, and Assistance Animals, and

- Accessibility and Inclusive Resources

All the exercise materials noted previously follow the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Homeland Security Exercise and Evaluation Program (HSEEP).[32] FEMA has expanded the training for exercises of all types, beyond the single in-person and online training, and to include a leadership certification program – the Master Exercise Practitioners (MEP) Program – at the U.S. national level.[33]

While neither author is certified as an MEP, Prasad has completed the basic HSEEP training, used multiple roles in large-scale exercises as his primary qualification aspect for his Certified Emergency Manager® credential,[34] and the material produced for the NMCE was aligned to HSEEP standards and practices. Prasad has regularly utilized the HSEEP construct in his emergency management training and consulting work.[35] MEPs did collaborate on the creation of this exercise material as well.

Discussion and Implications

The authors are actively working to solve this concern, not just admiring it (Rimmer 2022). The chapter documents the work so far, which has followed both a top-down and bottom-up grassroots change-management workflow, one for which other pracademic (Crowley n.d.) researchers can undertake to effect policy and procedural modifications for these and other life safety issues. The pathways taken through this specific pediatric mass care concern will be beneficial to other researchers, policymakers, practitioners, as well as academics in making similar changes to plans, organization, equipment, training, and exercises for Emergency Management in many other aspects, beyond just changes to benefit infant and toddler feeding at disaster mass care sites. In many ways, the authors were uniquely positioned to work on these changes, and not just write about them: both authors are also American Red Cross volunteers,[36] with disaster experience at the state and national levels. Prasad, in his voluntary role as chair of the national children and disaster caucus of the International Association of Emergency Managers – USA was already connected to specific national leadership staff at FEMA, who are focused on improving and correcting adverse impacts to children before, during and after disasters.

Strong Example of the POETE Process across the entire disaster lifecycle (i.e., before, during, and after)

The author’s pracademic work is aligned with the continuous improvement agile project management process of POETE, which is a common problem-solving methodology used for the cyclical THIRA/SPR (FEMA 2018) process by states and territories in the United States, as well as the HSEEP After-Action/Improvement Plan template (FEMA n.d.) used by most SLTTs. It is applicable across the full disaster lifecycle in Emergency Management. As described in this chapter, this was the model utilized to build the targeted planning and exercise templates – to locally identify the need for further organizational constructs, equipment, and training – for the SLTTs, to utilize in developing their own whole-community belonging program of disaster feeding for infants and toddlers. This same structure can be applied to any country, any nation. The historically routine pathway for Emergency Management policy and procedural changes is for a catastrophic failure to occur, and then change is forced through legislation. This chapter provides an alternative route for systemic change, one that does not require human suffering and bureaucratic delays.

IDEA impacts to and from communities – and community engagement for resilience

The authors’ advocacy work also aligns to and promotes a stronger sense of belonging, through inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility (IDEA). Shelter operators benefit from connecting more closely with the entirety of the communities they serve. And of course, families are respected, supported, and empowered for their own family feeding choices made for any number of reasons. Those families are not treated like outsiders or outcasts. The first three of these elements of IDEA – inclusion, diversity, and equity – have significant background in policy and practice in the professional and academic world (Molefi, O’Mara and Richter 2021). The last – accessibility – is partly covered in practice outside of Emergency Management, with the same set of scoring/checklists for disabilities (Cornell University n.d.), but current research has only general C-MIST protocols (Kailes and Enders 2007) covered, and not further specifics associated with the various options for infant/toddler feeding (Mace, et al. 2018). Relying on the C-MIST only, can be ill-timed in terms of urgent infant/toddler feeding needs, lack of trust/connection between the sheltered family and shelter operators, and a considerable lack of pre-knowledge by the public as to their own preparedness efforts needed to support their family choice for infant/toddler feeding and what the capabilities and capacities of shelters in their jurisdiction can provide. Lactation counseling is a specific area where a nursing family may not have predetermined resources, especially if the first time they have lactation issues (latching, milk production, etc.) is because of an adverse impact of the disaster.

In 2021, U.S. President Joseph Biden issued an Executive Order (Biden, Jr. 2021), applicable to all U.S. Federal executive office and departmental employees. Many of these governmental groups applied these same principles to the U.S. families they serve:

- Inclusion – the recognition, appreciation, and use of the talents and skills of employees of all backgrounds.

- Diversity – means the practice of including the many communities, identities, races, ethnicities, backgrounds, abilities, cultures, and beliefs of the American people, including underserved communities.

- Equity – the consistent and systematic fair, just, and impartial treatment of all individuals, including individuals who belong to underserved communities that have been denied such treatment.

- Accessibility – the design, construction, development, and maintenance of facilities, information and communication technology, programs, and services so that all people, including people with disabilities, can fully and independently use them. Accessibility includes the provision of accommodations and modifications to ensure equal access to employment and participation in activities for people with disabilities, the reduction or elimination of physical and attitudinal barriers to equitable opportunities, a commitment to ensuring that people with disabilities can independently access every outward-facing and internal activity or electronic space, and the pursuit of best practices such as universal design (p.3) (FEMA 2023).

TEXT BOX 5: Not a Black Swan, but a Gray Rhino

Many may be familiar with the term “Black Swan” (Taleb 2007), which describes the extreme impacts from an unpredictable incident. Switching infants and toddlers from breastmilk to formula – solely and most critically, as an Emergency Management/shelter operator’s decision – is not that. Rather it is a “Gray Rhino” problem (Wucker 2016). These types of issues are predictable threats manifesting as life-safety hazards which Emergency Management (now) sees coming at them, and with a high probability of highly adverse impacts. Yet for some unknown reasons, collectively most choose to do nothing to avoid it. The authors have provided evidence and awareness that the current practices for infant and toddler feeding options during disasters in the United States are not working:

- They go against recommendations from multiple national and international health organizations,

- They do not account for any pre-existing cultural or religious aspects of the family,

- They can potentially cost the family extra expenses for formula after the incident has ended, which they may not be able to afford/may not be covered by grants or assistance programs, and

- They are currently the ‘easy way out’ for Emergency Management officials to ignore the massive threat which they in fact created and is squarely now in front of them.

Switching from breastfeeding to formula feeding – unless it is specifically requested by the family, with the guidance/advice of the disaster health professional on-scene – should not be considered a “reasonable accommodation” (p.12), as are other feeding options for people with DAFN (FEMA 2021).

Conclusion

The timing involved in writing this chapter and publishing this book precluded a final resolution to the problem statement. In other words, the story does not yet have a true conclusion. However, the authors felt quite strongly that the material in this chapter should be included in this book, for two major reasons. First and foremost, time is of the essence. Infants and toddlers cannot wait for bureaucracy and organizational tardiness to eat a healthy, nutritious meal during a disaster, one based on their own family’s choice. Everyone involved in Emergency Management who now knows about this problem needs to do something positive about this problem. Changes to the way every society operates disaster feeding now must be made. In the authors’ opinion, as you have now read this chapter, regardless of your position or role: This now includes you. You now have a professional and ethical duty to be part of the solutions for family choice in infant/toddler feeding, which are needed now for the community/communities you are a part of.

It is recommended that the reader visit the author’s work in progress – currently online at https://bartondunant.com/pediatric-feeding[37] – to learn more about what is being done. At some point, if all goes as planned, this information will also be located online at the National Mass Care Strategy’s website, found at https://nationalmasscarestrategy.org/. Please find out how you can make your own jurisdiction better, regardless of what role you have in Emergency Management.

The story about how the authors got from “there to here” deserves to be memorialized, studied, and expanded upon. Not only do the authors encourage others solve their own jurisdiction’s pediatric mass care feeding concerns from a whole-of-community, full-cycle basis – as professional Emergency Managers should – they welcome other pracademic researchers and practitioners to amplify any advocacy for a top-down and bottom-up grassroots approach to global changes to disaster policies, procedures, doctrine, etc. Figure 4 shows a few of their key milestones between 2023 and 2024. Please see Appendix B for highlights of additional pracademic research and advocacy milestones, as of the publishing date.

Appendix A

The national-level guidance on mass care feeding for state, local, tribal, and territorial organizations (SLTTs) comes from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and is sourced from their toolkits[38] and the National Mass Care Strategy website,[39] which provides a consolidated and comprehensive set of guidance material from governmental and nongovernmental mass care experts. The U.S. Health and Human Services (HHS) Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have also produced a Maternal-Child Health (HHS MCH) Emergency Planning Toolkit.[40] The HHS MCH Toolkit is primarily designed for healthcare providers, public health officials, social services providers, and others but has community partners, organizations, and emergency managers as a secondary audience.

State, local, tribal, and territorial organizations must review and revise their mass care feeding response plans to better support pediatric feeding needs.

In contrast, the primary audience for the CDC Infant and Young Child Feeding in Emergencies Toolkit[41] are emergency preparedness and response personnel and disaster response organizations. These resources outline and highlight the need to make pediatric feeding a priority. Thus they should be reviewed, and their guidance incorporated into the SLTT’s emergency response planning.

Although these guidelines recommend how SLTTs should effectively and tactically provide this feeding support to infants and toddlers, they do not have the needed whole-community partnerships established for each SLTT. For example, while the Commonly Used Sheltering Items (CUSI)[42] list and other FEMA doctrine[43] strongly focus on feeding infants and toddlers with commercial infant formula, they omit the need for quick provision of breastfeeding supplies and support. The U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans[44] recommend exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months with continued breastfeeding while adding appropriate complementary foods for two years or beyond as long as mutually desired by the mother and child. Despite these recommendations, federal guidelines do not point SLTTs to vendors of breast pumps, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) who have breast pumps available for loan or donation, etc. SLTTs must estimate and plan for the logistical distribution and cost[45] of breastfeeding and re-lactation[46] supplies along with safe[47] alternatives to mothers’ breastmilk and other pediatric feeding items.

SLTTs must also eliminate barriers[48] (such as the pre-disaster written authorization[49] from a medical provider for breastfeeding equipment needs) to obtain breastfeeding support and supplies, understanding that breastfeeding is the best form of nutrition[50] for most babies. Thus, procuring resources to support breastfeeding is an immediate critical and life-sustaining need. Breastfeeding supplies should be added to the Commonly Used Sheltering Items Catalog with durable medical equipment, personal assistance services, and consumable medical supplies to support people with Disabilities and Access/Functional Needs (DAFN) in congregate care shelters and other disaster sites where mass care feeding occurs. SLTTs must ensure that the process of obtaining personal assistance and medical supplies does not delay feeding, thus causing food insecurity for infants and toddlers.

SLTTs must perform these feeding missions[51] through a culturally sensitive and equitable distribution model at disaster shelters, aid stations, and other locations where general population disaster feeding occurs. Challenges today include several erroneous assumptions on the part of emergency managers, for example:

- Evacuating mothers have all the feeding supplies with them when they evacuate;

- Switching feeding methods (commercial infant formula in lieu of human milk, a different type of formula than what the child normally has, etc.) is a reasonable accommodation and indemnifies the SLTT from its responsibilities for proper disaster mass care feeding of everyone adversely impacted;

- Mothers are able to find their own feeding support, including milk storage, without the assistance of trained shelter staff and lactation providers;

- Even with donations of some supplies – such as shown in the cover photo from Katrina – SLTT shelters will not need provisions for human-milk production and storage, including durable medical equipment, associated consumable medical supplies (breast pumps and other lactation supplies: bottles, nipples, etc.), private space within the shelter, and other shelter protocols and procedures[52] in support of breastfeeding by mothers for their – and potentially any other family’s – infants and toddlers; and

- At the SLTT level, another entity, organization, etc. would be responsible for the proper feeding capabilities at congregate care disaster shelters and other disaster sites where mass care feeding occurs.

- These disconnects are often exacerbated by existing low-levels of whole-community planning for people with DAFN, at the SLTT levels. A metric of adopting the CMIST Framework[53](Communication, Maintaining Health, Independence, Support, Transportation) for shelter resident intake is one measure of a positive application of planning for at-risk individuals with DAFN, including pregnant women and mothers with infants/toddlers.

SLTTs model their own logistical support for sheltering against the CUSI Catalog so they can be reimbursed on declared disasters. Those formula items are also part of infant/toddler kits that SLTTs can order through the same disaster resource request[54] process as other items and mission assignments from FEMA. As with any other tactical federal assistance requests, these need to be prioritized by the SLTTs and requested as soon as possible. The Update to FEMA’s Individual Assistance Program and Policy Guide, Version 1.1, also omits breastfeeding. However, there are U.S. congressionally proposed plans[55] to update the 2023 version to include breastfeeding.

Benefits of Pre-Planning on a Whole-Community Basis

There are benefits to SLTTs and nongovernmental organizations beyond covering pediatric feeding needs when incorporating whole-community planning for mass care feeding.

The relationships established between steady-state governmental organizations with nongovernmental organizations for pediatric feeding benefit governmental organizations for their non-disaster work. For example, MOUs, MOAs, and other collaborations between milk banks[56] and public health officials, child protective agencies, and social services organizations, will strengthen those SLTTs’ own daily operations and constituent support. Jefferson County, Colorado Public Health[57] created a formal emergency plan and implemented a safe infant feeding project. The plans, training information, and resources specific for their jurisdiction are on their Emergency Preparedness page.[58]

Nongovernmental organizations supporting the disaster needs of SLTTs should be integrated into the emergency response planning – including being identified as critical infrastructure/key resources (CI/KR)[59] – and benefit from any mitigation efforts afforded to other CI/KR assets. Restoration of their functionality – if adversely impacted by a disaster – should be prioritized along with other CI/KR feeding assets such as food banks, USDA warehouses, etc.

The amplification of pediatric feeding needs within SLTTs should also elevate other children and disaster needs, as well as the disaster-impact needs of people with DAFN. Examples include positive impacts on interim and long-term recovery, community lifeline support, and other disaster cycle mission essential functions.

HHS MCH Toolkit Recommendations

The HHS MCH Toolkit is comprehensive on the checklist type of considerations the public and shelter operators need to incorporate before, during, and after disasters. FEMA indicated that this guidance, which expands well beyond just feeding, was created through whole-community coordination, including the U.S. Breastfeeding Committee[60] and other groups.

The following list was adapted from the HHS-ASPR, May 2021, HHS MCH Toolkit[61] Shelter Considerations to Support MCH Populations in Emergency Response:

- Require background checks for shelter personnel.

- Train personnel to identify signs of human trafficking and abuse:

- See the CDC website for resources for Shelter Personnel on Human Trafficking in the Wake of a Disaster[62]

- Call the National Human Trafficking Hotline (888-373-7888 or text “HELP” to 233733); and

- Report suspected child exploitation to the CyberTipline, The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, at 1-800-THE-LOST.

- Initiate a rapid needs assessment system[63]for infants and young children to assess feeding support and resource needs.

- Provide safe, private spaces for infant feeding equipped with comfortable chairs, footstools, outlets, a sink with clean water and dish soap, refrigerated space with bins to store breastmilk/food, and signage for a designated breastfeeding area (a mother may breastfeed in any public or private space she is authorized by law).[64]

- Provide breastfeeding supplies, including: breast pumps (electric, battery-operated, and manual ones for disaster scenarios where continuous power at the shelter site may be in question); breast pump quick clean wipes and steam cleaning bags; breast milk storage bags; nursing pads and soothies; nipple cream or lanolin; nursing cover; nursing pillow; sound information[65] about pumping, increasing milk supply, and re-lactating; and nutritious food and clean water for the mother.

- Supply diapers, baby wipes, bottles, nipples, disposable cups, ready-to-feed infant formula, pacifiers, clean water, infant feeding and cleaning supplies, feminine hygiene products (e.g., sanitary napkins), and child-size equipment (e.g., beds, masks as advised by public health officials) to women who are pregnant, postpartum, or lactating as well as to infants and young children.

- Adhere to safe sleep[66] guidelines for infants and safer sleep guidelines for exclusively breastfed infants[67] who meet specific criteria. For more information, see Planning Considerations for Infants (ages 0-12 months) in Emergencies.

- Provide essential social services independently or through partnerships with local social service organizations, including nutrition, breastfeeding support, and healthcare referrals.

- Initiate a referral system for women who are pregnant and go into labor, who show signs of labor or pregnancy loss, or who are in the postpartum period and show problems to healthcare providers and emergency medical services.

- Initiate a referral system for lactating women who experience problems, such as difficulty feeding, breast pain, and low milk supply, to International Board-Certified Lactation Consultants (IBCLC) and healthcare providers.

- Provide access to services for testing and treatment, such as sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and emergency contraception.

- Staff individuals who represent the community in terms of demographics and culture.

- Provide access to medical interpretation and translation services.

Applying the best practices found in the HHS MCS and CDC toolkit should benefit all SLTTs, which should undertake the deep dive needed for tactical logistics pre-planning for acquiring and distributing supplies and equipment for pediatric feeding. Multi-state disasters, including worldwide pandemics,[68] can severely impact breastfeeding support. Even infant and specialty formula itself has been the subject of recent product-process disasters[69] and significantly impacted socially vulnerable populations around the world, even without the additional adverse impacts from a natural or human-made disaster. Therefore, SLTTs should be better prepared to respond and recover from any type of disaster, and their ability to safely, effectively, equitably, and quickly provide pediatric feeding support is paramount.

© Reprinted with permission from the Texas Division of Emergency Management. Originally published in the May 2023 edition of the Domestic Preparedness Journal (https://domesticpreparedness.com/articles/challenges-with-pediatric-mass-care-feeding).

Appendix B – Milestones Timeline

|

Pediatric Feeding Concerns – Pracademic Research and Advocacy Milestones. For a more updated list, please visit https://bartondunant.com/pediatric-feeding |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Timeframe |

Milestone

|

Status |

|

March 27, 2023 |

Russell presents problem statement to IAEM-CAD Caucus. |

Completed |

|

March 31, 2023 |

Prasad starts discussions with FEMA about PA/Category B, Recovery Assistance, CUSI listing, FNSS updates, NMCS website.

|

In Progress |

|

May 10, 2023 |

Prasad and Russell co-author article in the Domestic Preparedness Journal. |

Published |

|

April, 2023 |

Prasad starts discussions with various groups within Disaster Cycle Services at the American Red Cross’ national headquarters, including Mass Care and Disaster Health Services.

|

In Progress |

|

September 10, 2023 |

As part of work to increase content to be made available for the National Mass Care Strategy Website, Prasad hosts the first of three “Build-a-Tabletop Exercise” series, to build a template for a table-top exercise which SLTTs can use to help them pre-plan and pre-stage support for breastfeeding at future mass care shelters and fixed feeding sites. |

Ongoing |

|

November, 2023 |

Authors’ problem statement approved for inject and other pre-exercise work for the 2024 National Mass Care Exercise, held in Shippensburg, PA.

|

Completed |

|

November 1, 2023 |

Russell co-leads web panel on “Infant and Young Child Feeding in Emergencies: Preparedness Systems for Communities to Keep Babies Safe”, with the US Breastfeeding Committee and the National Association of County and City Health Officials. |

Completed |

|

December 1, 2023 |

Prasad received Institutional Review Board approval for exempt research on the American Red Cross sheltering records, from American Public University (2023-095).

|

Approved |

|

January, 2024 |

Red Cross indicates it does not have historic feeding data, from the Logistical requisition perspective. Prasad continues to explore other dataset research options at the Red Cross. |

Declined |

|

January, 2024 |

Prasad received initial research results from the Red Cross, on demographics of large-scale disaster recovery case work for families, for the past three years. Averaging 3% year-over-year, for children ages 2 and under. This will be utilized as the default denominator in further research, as well as the factoring number for logistics support ‘best case’ defaults (3 for every 100).

|

Completed |

|

January 25, 2024 |

Prasad reaches out to the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, for modifications to their “Infection Prevention and Control for Shelters during Disasters” guidelines [70] related to shelter-based breastfeeding activities. |

Open |

|

February, 2024 |

Created Spanish-language version of problem statement presentation, for use in Puerto Rico.

|

Completed |

|

March, 2024 |

Prasad contacts PREMA to coordinate a Spanish-language version of the problem statement, utilizing native Spanish speakers with public health expertise. |

Open |

|

March, 2024 |

Prasad received decline notice from FEMA’s Higher Education Program to present problem statement at the 26th Annual FEMA Emergency Management Higher Education Symposium.

|

Declined |

|

April, 2024 |

Prasad received notification of acceptance of problem statement into IAEM-USA’s annual conference’s pre-conference virtual webinars, scheduled for October 2024. |

Open |

|

May, 2024 |

Russell presents problem statement to Maine State Breastfeeding Coalition on a webinar, with MEMA Mass Care lead. |

Completed |

|

May, 2024 |

Prasad observes the National Mass Care Exercise (Keystone 6) in Pennsylvania and reports findings to the After-Action Report/Improvement Plan |

Completed |

|

May, 2024 |

Prasad introduces FEMA’s Office of Disability Integration & Coordination to the problem statement. |

Open |

| May, 2024 | National Mass Care Strategy’s Feeding page on their website now includes notice of Infant/Toddler Feeding Support in Shelters.[71] |

Closed |

| June, 2024 | Prasad communicates with Healthcare Ready (healthcareready.org) to inquire if they want to help with DME and CMS logistics, especially from retail pharmacies. | Open |

|

June, 2024 |

Prasad provides comments for FEMA’s new Planning Considerations: Putting People First guidance document, during public comment period.

|

Open |

References

Administration for Children and Families (ACF). 2020. “Infant Feeding During Disasters.” https://www.acf.hhs.gov. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ohsepr/resource-library?page=3.

American Academy of Pediatrics. 2020. “Infant Feeding in Disasters and Emergencies: Breastfeeding and Other Options.” https://downloads.aap.org/AAP/PDF/DisasterFactSheet-2020_English.pdf.

Barton Dunant. 2018. “Shrink the Pink Slice!” Blog.BartonDunant.com. Accessed December 11, 2023. https://blog.bartondunant.com/what-is-the-pink-slice/.

Biden, Jr., J R. 2021. Executive Order on Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility in the Federal Workforce. Presidential Executive Order, Washington: The White House. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/06/25/executive-order-on-diversity-equity-inclusion-and-accessibility-in-the-federal-workforce/.

Birkland, Thomas. 1998. “Focusing Events, Mobilization, and Agenda Setting.” Journal of Public Policy (Cambridge University Press) 18 (1): 53-74.

Callaghan, W. M., S. A. Rasmussen, D. J. Jamieson, S. J. Ventura, S. L. Farr, P. D. Sutton, T. J. Mathews, et al. 2007. “Health Concerns of Women and Infants in Times of Natural Disasters: Lessons Learned from Hurricane Katrina.” Maternal and Child Health Journal 11 (4): 307-311. doi:https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10995-007-0177-4.

Catalino, J. 2015. The Impact of Federal Emergency Management Legislation on At-Risk and Vulnerable Populations for Disaster Preparedness and Response. Dissertation, Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies. https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations/572.

Catalino, Joseph. 2015. “The Impact of Federal Emergency Management Legislation on At-Risk and Vulnerable Populations for Disaster Preparedness and Response.” Doctoral Dissertation, College of Social and Behavioral Sciences , Walden University. Accessed June 20, 2024. https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?params=/context/dissertations/article/1571/&path_info=Catalino_waldenu_0543D_16046.pdf.

Communication Theory. N.D. The Johari Window Model. Accessed June 20, 2024. https://www.communicationtheory.org/the-johari-window-model/.

Cooper, M. 2007. Pathways to Change: Facilitating the Full Civic Engagement of Diversity Groups in Canadian Society. Calgary, Alberta, Canada: Government of Alberta.

Cornell University. n.d. Working to advance disability inclusion. Accessed February 12, 2024. https://yti.cornell.edu/.

Crawford, T, I Yen, K -y Chang, G Llewellyn, D Dominey-Howes, and M Villeneuve. 2023. “How well prepared are we for disaster? The perspectives of informal carers of people with disability.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 93: 103785. doi:https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.103785.

Crowley, K. n.d. Pracademic: bridging the gap between science and practice for disaster management and climate change adaptation. Web Presentation, The University of Edinburgh. https://www.ed.ac.uk/files/atoms/files/pracademic.pdf.

Cutter, Susan L, and Sahat Derakhshan. 2019. “Implementing Disaster Policy: Exploring Scale and Measurement Schemes for Disaster Resilience.” Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management 16 (3): 20180029. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/jhsem-2018-0029.

de Vries, D H, J Kinsman, J Takacs, S Tsolova, and M Ciotti. 2020. “Methodology for assessment of public health emergency preparedness and response synergies between institutional authorities and communities.” BMC Health Services Research 20: 411. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05298-z.

Delfmann, W, W Dangelmaier, W Günthner, P Klaus, L Overmeyer, W Rothengatter, J Weber, J Zentes, and Working Group of the Scientific Advisory Board BVL. 2010. “Towards a science of logistics: cornerstones of a framework of understanding of logistics as an academic discipline.” Logistics Research 2: 57-63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12159-010-0034-5.

Denning, Stephen. 2010. The Leader’s Guide to Radical Management: Reinventing the Workplace for the 21st Century. Jossey-Bass.

DeYoung, S. E., J. Chase, M. P. Branco, and B. Park. 2018. “The Effect of Mass Evacuation on Infant Feeding: The Case of the 2016 Fort McMurray Wildfire.” Maternal Child Health Journal 22 (12): 1826-1833. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2585-z.

DeYoung, S., M. Suji, and H. G. Southall. 2018. “Maternal Perceptions of Infant Feeding and Health in the Context of the 2015 Nepal Earthquake.” Journal of Human Lactation 34 (2): 242-252. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334417750144 .

Dickinson, Jill, Andrew Fowler, and Teri-Lisa Griffiths . 2022. “Exploring transitions and professional identities in higher education.” Studies in Higher Education 47 (2): 290-304. doi:10.1080/03075079.2020.1744123.

Doran, G T. 1981. “There’s a S.M.A.R.T. Way to Write Management’s Goals and Objectives.” Management Review 70: 35-36.

Drabek, Thomas Ed. 1984. “Some Emerging Issues in Emergency Management.”

Emergency Nutrition Network (ENN). 2017. “Infant and Young Child Feeding in Emergencies: Operational guidance for emergency relief staff and programme managers, 52.” https://www.ennonline.net/operationalguidance-v3-2017.

FEMA. 2022. “Commonly Used Sheltering Items Catalog.” Accessed April 23, 2024. https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_commonly-used-sheltering-items-catalog.pdf.

FEMA. 2020. “Homeland Security Exercise and Evaluation Program Doctrine 202 Revision 2-2-25.” FEMA.gov. Accessed February 12, 2024. https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-04/Homeland-Security-Exercise-and-Evaluation-Program-Doctrine-2020-Revision-2-2-25.pdf.

FEMA. 2023. Inclusion, Diversity, Equity and Accessibility in Exercises Considerations and Best Practices Guide. Washington: FEMA. https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_inclusion-diversity-equity-accessibility-exercises.pdf.

FEMA. 2021. Individual Assistance Program and Policy Guide (IAPPG) Version 1.1. FEMA. https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_iappg-1.1.pdf.

FEMA. 2020. Public Assistance Program and Policy Guide Version 4. FEMA. https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_pappg-v4-updated-links_policy_6-1-2020.pdf.

FEMA. 2018. Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment (THIRA) and Stakeholder Preparedness Review (SPR) Guide Comprehensive Preparedness Guide (CPG) 201 3rd Edition. FEMA.

Franzosi, R. 1998. “Narrative Analysis-Or Why (And How) Sociologists Should be Interested in Narrative.” Annual Review of Sociology 24: 517–554. http://www.jstor.org/stable/223492.

Freitag, B, T Hicks, A Jerolleman, and W Walsh. 2020. “Storytelling—Plots of resilience, learning, and discovery in emergency management.” Journal of Emergency Management 18 (5): 363-371. doi:10.5055/jem.2020.0485.

Fuentealba, R., H. Verrest, and J. Gupta. 2020. “Planning for Exclusion: The Politics of Urban Disaster Governance. Politics and Governance.” Politics and Governance 8 (4): 244-255. doi:https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v8i4.3085.

General Accounting Office. 2017. DEFENSE CIVIL SUPPORT DOD, HHS, and DHS Should Use Existing Coordination Mechanisms to Improve Their Pandemic Preparedness. Report to the Committee on Armed Services, House of Representatives, United States Government Accountability Office. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-17-150.pdf.

GovStar. n.d. “HHS Federal Lead for COVID-19.” govrisk.com. Accessed December 5, 2023. https://www.govrisk.com/article/hhs-federal-lead-for-covid-19.

Gribble, K, M Peterson, and D Brown. 2019. “Emergency preparedness for infant and young child feeding in emergencies (IYCF-E): an Australian audit of emergency plans and guidance.” BMC Public Health 19 (1): 1278. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7528-0.

Gribble, K. D., and A.E. L. Palmquist. 2022. “We make a mistake with shoes [that’s no problem] but… not with baby milk.” Maternal & Child Nutrition 18 (1): e13282. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.13282.

Grubesic, T H, and K M Durbin. 2022. “Breastfeeding, Community Vulnerability, Resilience, and Disasters: A Snapshot of the United States Gulf Coast.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (19): 11847. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911847.

Hirani, S.A. A. 2022. “Caring for breastfeeding mothers in disaster relief camps: A call to innovation in nursing curriculum.” Science Talks 4: 100089. doi:https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sctalk.2022.100089.

Hoffman, Jenn, and Sarah Henly-Shepard. 2023. Nature-based Solutions for Climate Resilience in Humanitarian Action. SPHERE. https://friendsofeba.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/sphere-nbs-23-04-2023-english.pdf.

Hunt, L, G Thomson, K Whittaker, and F Dykes. 2021. “Adapting breastfeeding support in areas of socio-economic deprivation: a case study approach.” International Journal for Equity in Health 20 (1): 83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-021-01393-7.

Hwang, C. H., A. Iellamo, and M. Ververs. 2021. “Barriers and Challenges of Infant Feeding in Disasters in Middle- and High-Income Countries.” International Breastfeeding Journal 16: 1-13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-021-00398-w.

IFE Core Group. 2017. “Infant and Young Child Feeding in Emergencies – Operational Guidance for Emergency Relief Staff and Programme Managers.” Emergency Nutrition Network. Accessed January 5, 2024. https://www.ennonline.net/attachments/3127/Ops-G_English_04Mar2019_WEB.pdf.

Jerolleman, Alessandra. 2021. “Storytelling and Narrative Research in Crisis and Disaster Studies.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1615.

Jung, Jinho, Nicole Olynk Widmar, and Brenna Ellison. 2023. “The Curious Case of Baby Formula in the United States in 2022: Cries for Urgent Action Months after Silence in the Midst of Alarm Bells.” Food Ethics 8 (1): 4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s41055-022-00115-1.

Kailes, J. I., and A. Enders. 2007. “Moving Beyond “Special Needs”: A Function-Based Framework for Emergency Management and Planning.” Journal of Disability Policy Studies 17 (4): 230-237. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/10442073070170040601.

Kapucu, N. 2008. “Collaborative emergency management: Better community organising, better public preparedness and response.” Disasters 32: 239-262. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7717.2008.01037.x .

Kargillis, C, M Kako, and D Gillham. 2014. “Disaster Survivors: A Narrative Approach Towards Emotional Recovery.” Australian Journal of Emergency Management 29 (2): 25-30.

MacDonald, T., J. Noel-Weiss, D. West, M. Walks, M. Biener, A. Kibbe, and E. Myler. 2016. “Transmasculine individuals’ experiences with lactation, chestfeeding, and gender identity: a qualitative study.” BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 16: 106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0907-y.

Mace, C. E., C. J. Doyle, K. Askew, S. Bradin, M. Baker, M. M. Joseph, and A. Sorrentino. 2018. American Journal of Disaster Medicine 13 (3): 207-220. doi:https://doi.org/10.5055/ajdm.2018.0301.

Marcus, Len Jay, Beta Cara Dorn, and Jay May Henderson. 2006. “Meta-leadership and national emergency preparedness: A model to build government connectivity.” Biosecurity and Bioterrorism : Biodefense Strategy, Practice, and Science 4 (2): 128-134. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/bsp.2006.4.128.

Mike, M, R Mike, and C J Lee. 2011. “Katrina’s Animal Legacy: The PETS Act.” Journal of Animal Law & Ethics 4: 133. https://advance-lexis-com.ezproxy1.apus.edu/api/document?collection=analytical-materials&id=urn:contentItem:56VD-HDD0-02C9-K04H-00000-00&context=1516831.

Mills, C W. 1956. The Power Elite. New York: Oxford University Press.

Molefi, N., J. O’Mara, and A. Richter. 2021. Global Diversity, Equity & Inclusion Benchmarks: Standards for Organizations Around the World. QED Consulting. https://www.qedconsulting.com/component/content/article/104-services/products/161-global-diversity-equity-inclusion-benchmarks?Itemid=566.

National Mass Care Strategy. n.d. Mission and Purpose. Accessed December 29, 2023. https://nationalmasscarestrategy.org/lp-profile/home-2/about-us/mission-and-purpose/.

Olson, R S, R A Olson, and V T Gawronski. 1998. “Night and Day: Mitigation Policymaking in Oakland, California before and after the Loma Prieta Disaster.” International Journal of Mass Emergencies & Disasters 16 (2): 145-179. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/028072709801600202.

Pahwa, Anmol, and Miguel Jaller. 2023. “Assessing last-mile distribution resilience under demand disruptions.” Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 172: 103066. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2023.103066.

Peters, T J, and R H Waterman. 1982. In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America’s Best-Run Companies. New York: Harper & Row.

Prasad, Michael. 2024. Emergency Management Threats and Hazards: Water. CRC Press. https://www.routledge.com/Emergency-Management-Threats-and-Hazards-Water/Prasad/p/book/9781032755151.

Prasad, Michael, and Jennifer Russell. 2023. “Challenges with Pediatric Mass Care Feeding.” Domestic Preparedness Journal 19 (5): 27-31. https://domesticpreparedness.com/articles/challenges-with-pediatric-mass-care-feeding.

Quarantelli, Ed La. 1995. “Patterns of sheltering and housing in US disasters.” Disaster Prevention and Management 4 (3): 43-53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09653569510088069.

Quinn, D., S. V. Lavigne, C. Chambers, L. Wolfe, H. Chipman, J. D. Cragan, and S. A. Rasmussen. 2008. “Addressing concerns of pregnant and lactating women after the 2005 hurricanes:The OTIS response.” The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing 33 (4): 235-241. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NMC.0000326078.49740.48 .

Rimmer, J H. 2022. “Addressing Disability Inequities: Let’s Stop Admiring the Problem and Do Something about It.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 11886. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191911886.

Santaballa Mora, L. M. 2018. “Challenges of Infant and Child Feeding in Emergencies: The Puerto Rico Experience.” Breastfeeding Medicine 13 (8): 539-540. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2018.0128 .

Scott, B. L., M. Montoya, A. Farzan, M. Cruz, M. Jaskela, B. Smith, M. LaGoy, and J. Marshall. 2022. “Barriers and Opportunities for the MCH Workforce to Support Hurricane Preparedness, Response, and Recovery in Florida.” Maternal & Child Health Journal 26 (3): 556-564. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-021-03351-9.

Stachowiak, C. 2013. “Pathways for Change: 10 Theories to Inform Advocacy and Policy Change Efforts.” ORS Impact 11. https://www.orsimpact.com/DirectoryAttachments/132018_13248_359_Center_Pathways_FINAL.pdf.

Taleb, Nicholas. 2007. The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. United States: Random House.

U.S. Government Accountability Office. 2016. Emergency Communications Effectiveness of the Post-Katrina Interagency Coordination Group Could Be Enhanced. GAO. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-16-681.pdf.

United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. 2015. “Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030.” Geneva: United Nations.

US Centers for Disease Control. 2023. Infant and Young Child Feeding in Emergencies. Accessed December 11, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/emergencies-infant-feeding/index.html.