1 Introduction to the Management of International Disasters: Pressing Issues and Collaboration Between Nations

Laura M. Phipps, DrPH, MPH, CPH, RS and David A. McEntire, PhD, SFHEA

Authors

Laura M. Phipps, DrPH, MPH, CPH, RS, University of Texas at Arlington

Dave A. McEntire, PhD, SFHEA Utah Valley University

Keywords

international emergency management, disasters, collaboration, public health, security

Introduction

FEMA firmly believes in the depth and breadth of a global emergency management community. Collaboration, communication, and swift action among foreign partners supports the “whole of community” emergency management mission before, during, and after disasters. Hazards of all types bring disaster response to the world’s stage, with emergency managers at the forefront (Federal Emergency Management Agency 2022).

On September 10th, 2023, Storm Daniel ripped through the northeastern region of Libya, bringing high winds and torrential rains. The subsequent flooding ultimately overwhelmed and broke two dams, allowing over 30 million cubic meters of floodwaters to sweep through the area and wipe out an estimated thirty percent of the coastal town of Derna (Center for Disaster Philanthropy 2024; European Commission 2023b). Structural consequences of the destruction in Derna, Libya can be viewed in Figure 1. Exact numbers vary, but it is estimated that as a result of this storm, at least 4,300 people in Libya died, 8,500 people are still missing, and 1.8 million people in the area were affected (UN News 2023).

The international response to this disaster was swift as global response agencies and organizations, including multiple UN agencies, USAID, the International Medical Corps, and the European Union, came to the aid of Libyan victims (European Commission 2023b; International Medical Corps 2024; USAID 2024). The World Health Organization (WHO) was on the ground providing psychological aid for those suffering from post-traumatic grief and anxiety and conducting infectious disease surveillance in hospitals and shelters to detect and control epidemics (Oduoye et al. 2024). Humanitarian aid from other national governments, such as Turkey, Italy, France, Iran, Jordan and Algeria, also flooded into the hardest hit regions of Libya (Reuters 2023; Al Jazeera 2024).

Despite the overwhelming response from the international community, the recovery of this region of Libya has been complex, obstructed and shaped by weak infrastructure and resources and driven by political and social tensions in the region. Deep political fractures have plagued the two opposing governments in Libya, which lacks a strong central government and has been in intermittent conflict since 2011 (Arab Center Washington 2023; Al Jazeera 2024). The country has high rates of poverty and is beset by militia groups involved in illicit economic activities and human trafficking (Arab Center Washington 2023). This context did not help when the flood dams broke in 2023 and floodwaters swept over the region. Most roads in the area collapsed, major roads between towns were blocked, healthcare facilities were wiped out, and cities were beset with power outages and loss of communication (UN News 2023). Children have been especially vulnerable to adverse effects of the flooding due to their increased chance of contracting waterborne diseases and suffering from malnutrition, interrupted schooling, and psychological trauma from loss of and separation from families (UNICEF 2023; Oduoye et al. 2024). The impacts of disasters can be truly astounding and present enormous challenges to the global emergency management community.

In this volume, we will explore disasters which have far-reaching effects that go beyond the immediate geographical area and impact bordering nations and beyond. We will look at why it is critical for us to concern ourselves with disasters that occur in countries far from our own borders and how these distant crises can have a direct or indirect impact on our environment and daily lives. We will examine complex issues that can arise when managing these types of international disasters. We will also explore the significant role of emergency management and relief agencies in handling these disasters abroad and why it matters how the disasters are managed.

This type of study is needed since recent humanitarian aid and refugee resettlement programs in countries such as Haiti, Myanmar and the Ukraine have faced significant challenges and have shown the need to broaden attention to disasters occurring in different parts of the world (European Commission 2023). In the same vein, our shared vulnerability to global infectious diseases was demonstrated throughout the recent global COVID-19 pandemic as health officials in communities around the world struggled to consistently and effectively communicate the latest findings and recommended infection prevention and control practices to mitigate disease transmission.

Practitioners also face a significant challenge in international emergency management due to the disparity between countries in their capacity to respond and recover from disasters (“Disaster Risk Reduction in Least Developed Countries” 2020). In addition to disasters caused by seismic and extreme weather events, nations also grapple with intentional emergencies such as terrorism, bioterrorism, and agroterrorism, which call for robust global health security measures and international cooperation. One of the book’s major contentions is that there is much to learn from the ways that other countries deal with disasters. Something can be learned from each country and population represented here.

Furthermore, the necessity for collaboration across nations is widely recognized, as disasters do not respect national borders and often impact multiple nations, calling for intentional cooperation and communication in emergency planning, response, and recovery efforts. However, such collaborations also present unique challenges and long-term outcomes, particularly when disasters undermine development efforts and foster a dependency on foreign aid.

Effective leadership and a well-trained network of emergency management professionals are therefore necessary for effectively facilitating international collaboration in response to disasters. Technology, while having the potential to worsen disparities, can also play a vital role in international emergency management and significantly contribute to the efficient recovery and progress of communities in the aftermath of a disaster. In the chapters that follow, we will dive deeper into these and other topics with the assistance of multiple perspectives. The chapter concludes with a forward-looking perspective on the future of international disaster management, considering the potential challenges and opportunities that lie ahead.

Context of Disasters

The context of global disasters is rapidly evolving due to factors such as climate change, urbanization, and socio-political dynamics (Awal 2015; Haggag et al., 2021; Sovacool et al., 2018). As a consequence, international emergencies can take multiple forms, including natural hazards such as hurricanes, earthquakes, and floods, as well as anthropogenic hazards, which include industrial accidents, chemical spills, armed conflict, war, and terrorism. Furthermore, although pandemics have occurred throughout history, the devastating effects of the recent global COVID-19 pandemic have even more clearly exposed our global vulnerability to infectious diseases.

Disasters and public health emergencies have resulted in a cumulative negative impact on humans and the environment, with an imbalanced impact on developing countries, exacerbating their lack of resilience and impeding recovery efforts. Disasters of all types will occur, cross borders, and have global implications. The increasing frequency and severity of global crises require a comprehensive approach to understanding and addressing the far-reaching impact of environmental and social factors on these events (Sovacool et al., 2018). The complexity and diversity of these emergencies demand proactive, comprehensive, and adaptable disaster management strategies through which emergency managers and responders can mitigate the impacts of these events and facilitate a swift and efficient recovery.

Natural Hazards

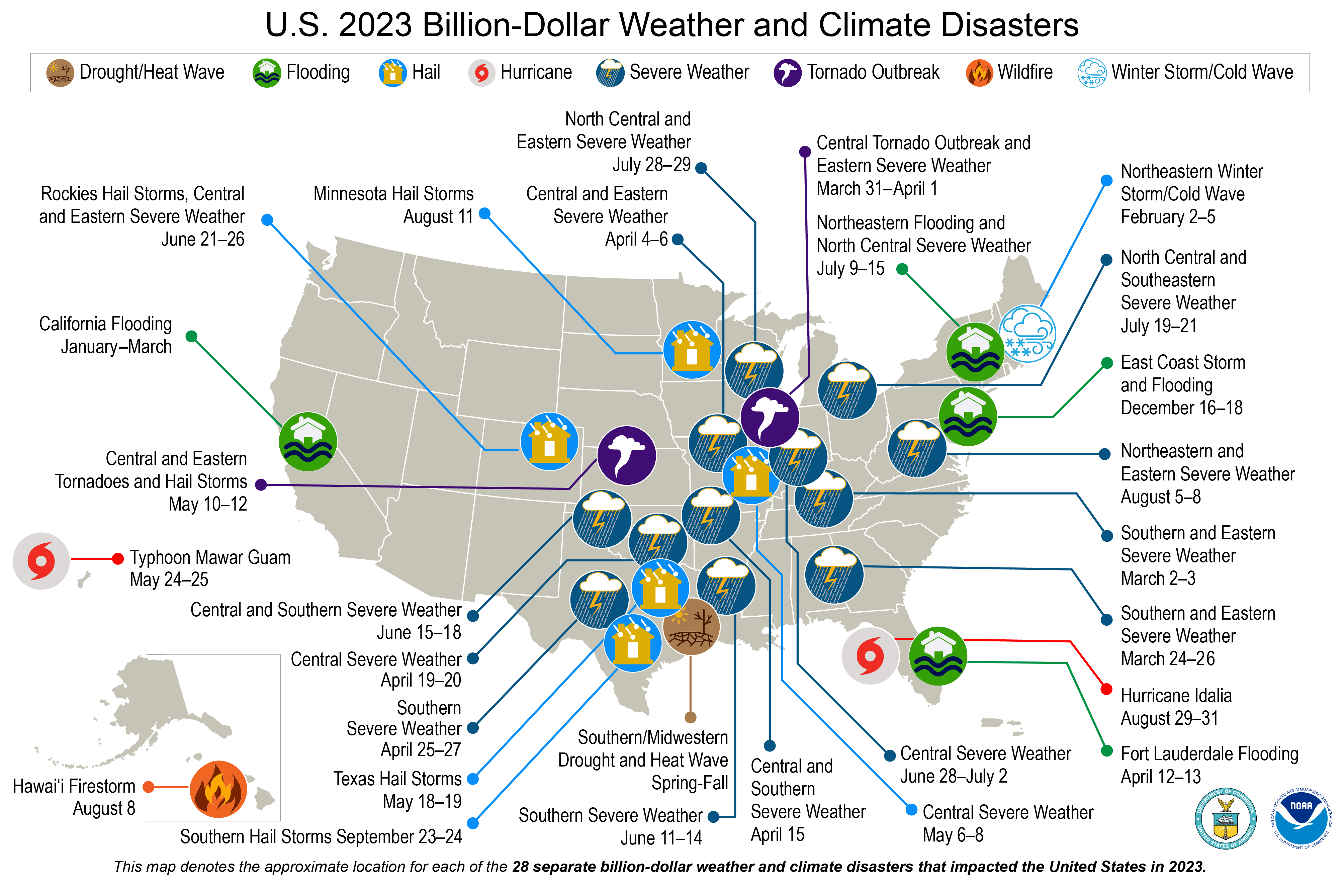

The past five decades have seen an unprecedented increase in hurricanes, wildfires, floods, and droughts, which are often attributed to the increasing effects of climate change. These effects have been particularly devastating to developing countries. While there was an average of 8.5 billion-dollar events every year between 1980-2023, between the years 2019-2023, there were 20.4 events each year (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association [NOAA] 2024). Locations of these events in 2023 are shown in Figure 2 (NOAA 2024). It is estimated that 3.3 million people have died over the past forty years due to the effects of disasters, most of them in developing countries (Kharb et al. 2022; UNDRR 2020). In addition, it is estimated that nearly 300 million people in 72 countries will require humanitarian assistance and protection in 2024 (European Commission 2023).

Besides becoming more frequent, hurricanes, cyclones and tropical storms have become more intense, leading to devastating consequences for coastal communities including the destruction of homes, municipal infrastructure and, in some cases, the destruction of whole communities. Wildfires have also become more common, particularly in regions with a warm climate, including parts of California, Australia, and the Mediterranean basin. These wildfires not only cause extensive property damage and loss of life but also contribute significantly to air pollution. Simultaneously, floods and droughts have become more prevalent due to changing precipitation patterns and higher evaporation rates due to increasing temperatures worldwide. Regions that used to receive steady rainfall are now experiencing more intense periods of rain followed by extended periods of dryness, leading to alternating periods of flooding and drought.

Natural hazards such as earthquakes and tsunamis form a significant portion of these disruptive events. They are unpredictable and can strike with little to no warning, leaving devastating consequences in their wake (Corbin et al. 2021; Feng and Cui 2021; Makwana 2019). The sheer force of nature displayed during these events can cause immense loss of life and property, leaving communities and nations in need of extensive recovery efforts.

Climate Change

Among the factors contributing to the increased frequency and severity of disasters, climate change stands out as a primary force. It is asserted that climate change has exacerbated weather patterns and contributed to more frequent and more severe disasters. As the effects of climate change grow more pronounced, global temperatures continue to rise, leading to more extreme weather patterns that manifest in the form of more frequent and severe disasters (Environment 2023; NASA 2024) The relationship between extreme weather events and climate change is cyclical and self-perpetuating. The damage caused by these events often leads to increased greenhouse gas emissions, which further exacerbate climate change. This, in turn, leads to more frequent and severe weather, creating a vicious cycle of destruction and environmental degradation.

The effects of these increasing temperatures are far-reaching. For instance, warmer ocean temperatures have been directly linked to the intensification of hurricanes, increased rainfall and subsequent flooding (European Commission 2023; NASA 2024; Environment 2023). Similarly, warmer air temperatures have led to higher evaporation rates, creating drier conditions and longer fire seasons and increasing the risk of wildfires (“Wildfire Climate Connection | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration,” n.d.). Desertification and drought are the unfortunate results of this situation.

Impact on Humans and the Environment

The escalating frequency and severity of natural hazards and climate change have had direct and far-reaching impacts on both human life and the environment. causing extensive damage, increased displacement and injuries, and loss of life (UNEP 2024). On the human front, these disasters have led to significant loss of life and displacement of communities. In addition to the immediate physical danger, they often result in economic hardship as homes, businesses, and infrastructure are destroyed.

The environmental impact has also been significant and, in many cases, similarly devastating. Natural hazards often lead to widespread habitat destruction, causing a significant loss of biodiversity and leading to extinction of freshwater fish and a decline in the number of saltwater fish (NOAA n.d.). Wildfires also decimate large areas of forest, destroying the habitats of countless species and reducing biodiversity. Furthermore, these events contribute to increased greenhouse gas emissions, which in turn exacerbate climate change.

The effective and efficient management of disasters at the global level requires international cooperation and coordination and necessitates that nations share responsibility for a country’s response and recovery from a disaster. This process involves the deliberate collaboration of countries and international organizations to prepare for, respond to, and recover from various global emergencies. Sharing resources and providing mutual aid during crises fosters the global community’s collective obligation to ensure every nation’s safety and recovery from threats.

However, challenges exist in globally managing disasters, particularly in resource sharing and providing humanitarian aid during emergencies. This book highlights what lies ahead for international disaster management. It addresses upcoming issues, raises awareness, and identifies existing resources, emphasizing that there is no need to reinvent the wheel if solutions exist.

Anthropogenic Threats

Unlike seismic and extreme weather events, anthropogenic threats such as nuclear accidents, chemical spills, industrial explosions, and wars are considered to be the direct result of human actions and decisions (Makwana 2019). Events like Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, Bhopal, and the recent and devastating fire ball in Beirut illustrate the dangers of mismanaged technology and harmful safety violations. Wars can also lead to widespread destruction, loss of life, and the displacement of millions of people (Leaning and Guha-Sapir 2013). The conflicts in Africa, the Middle East, Afghanistan, and the Ukraine are tragic reminders of the consequences of state sponsored violence. Adding to this complexity is the possibility of terrorism, which can be manifested through bombings and the use of other forms of mass destruction. State and non-state actors may also harness technology in nefarious ways. In fact, there is growing concern about the frequency and consequences of cyberattacks. Each of these threats, while rare, can have long-lasting impacts on people, the environment, health and infrastructure.

Public Health Emergencies

Over the past several decades, the world has witnessed a significant increase in the severity and frequency of infectious disease outbreaks, particularly those of zoonotic origin (USAID, 2024). This rise is largely attributable to the escalating proximity of humans and animals facilitated by human activities such as deforestation and the wider implications of climate change (USAID, 2024). As public health crises have increased in complexity over the past century due to globalization and increased mobility and density of humans in urban settings, infectious disease outbreaks have spread swiftly across borders, causing widespread health crises and disrupting national economies (Lawton, Luke 2013; Semenza et al. 2016).

The critical need for effective and responsive emergency preparedness measures during public health emergencies in all types of healthcare facilities, from outpatient clinics to long-term care facilities, became readily apparent during the recent COVID-19 pandemic (Herstein et al. 2021). Healthcare systems in vulnerable communities around the globe need to be strengthened and efforts invested to build capacities necessary to improve their emergency preparedness and resilience, particularly in areas vulnerable to infectious and neglected tropical diseases (Zhang et al. 2023).

In 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) was informed of an outbreak of Ebola virus disease in Guinea, Africa. The Director-General of WHO was reluctant to call it an outbreak, but Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) strongly disagreed and warned it was an Ebola epidemic that had the potential to transmit farther than ever before. By the time WHO declared it a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) on August 9th, 2014 and began sending supplies in October 2014, Ebola had already surged across the borders of Guinea (Packard 2016). Ebola cases soon overwhelmed the municipal infrastructure and healthcare systems in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. Patients began to avoid the healthcare clinics out of fear and the country leadership implemented mandatory curfews for the residents and disrupted medical transport services by closing borders (Parpia et al. 2016). By the end of the epidemic, over 28,000 individuals had become infected with Ebola and over 11,000 died (“Ebola Outbreak 2014-2016 – West Africa” n.d.)

As demonstrated by both the Ebola epidemic and COVID-19 pandemic, the threat posed by infectious diseases is far-reaching, extending well beyond the direct impact on human health and national security. It also has the potential to compromise the strength of various sectors including the social, political, and economic spheres (Ravi et al. 2020). Outbreaks of infectious diseases over the past several decades have led to a series of PHEICs, which have revealed the vulnerabilities within our existing health systems, the shortcomings of disease surveillance techniques, and the fragile nature of the global emergency management infrastructure (Zhang et al. 2023). One of the most devastating consequences of these emergencies has been the inability of countries to prevent and effectively respond to these emerging infectious diseases. This has resulted in an unimaginable human toll, with millions of people around the world losing not just their lives but also their livelihoods (USAID, 2024).

Infectious disease outbreaks can be initiated not only through natural transmission but intentionally as well. Nations are at risk for bioterrorism, in which one or more biological agents are used against a population, and agroterrorism, a terrorist attack targeting livestock animals and crops (“Animal Agrocrime and Agroterrorism,” n.d.). These events can cause widespread illness and casualties as well as indirect effects, such as civil unrest, mistrust of the government and economic loss. Biological threats necessitate leadership that is knowledgeable and skilled in managing public health crises (Htway and Casteel 2015; Lawton, Luke 2013). The control and eradication of global infectious diseases, such as Ebola, malaria and tuberculosis, will require better international cooperation with a higher level of urgency (Zhang et al. 2023).

Global Health Security

Effective global health security activities strengthen countries’ abilities to prepare for and respond to both terrorism attacks involving biological agents and infectious disease outbreaks. However, a primary challenge in international collaborative initiatives to address cross-border diseases is the disparity between countries in their ability to respond to recover from disasters.

An example of a collaborative global health security initiative designed to combat this disparity is the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA). In response to the growing global health crisis, the GHSA was launched in 2014. The GHSA is an extensive network comprising over 75 countries, international organizations, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that work together to improve and support countries’ infrastructure to detect, prevent, and respond to infectious disease threats (Global Health Security Agenda [GHSA], 2023). The GHSA has publicly established the goal to better strengthen global capacities to detect, prevent, and respond to outbreaks before they become epidemics and pandemics (GHSA, 2023). The GHSA has a systematic approach in its mission. It identifies measurable targets across a broad spectrum of 11 security areas. It then utilizes the resources available through its multisectoral partners to address existing gaps in a country’s emergency management infrastructure and systems. By doing this, the GHSA aims to bolster a country’s ability to prevent a disease outbreak, detect an outbreak in its early stages, and effectively respond to contain and manage such an outbreak (GHSA, 2023).

Addressing disparity in health systems across nations requires the measurement of the components of these systems. The health security of various countries was measured and categorized in 2019 and 2021 in the Global Health Security Index (GHS Index), which assesses the health security and related capabilities of 195 countries across six categories: prevention, detection and reporting, rapid response, health systems, compliance with international norms, and risk environment (“The 2021 Global Health Security Index” n.d.) The evaluators in this study determined that none of the countries is sufficiently prepared to face a severe infectious disease epidemic or pandemic in the future. However, it should be noted that there has been some recent concerns about the methods by which the GHS Index has ranked countries (Ravi et al. 2020).

Another entity in the global fight against infectious diseases is the USAID Global Health Security Program (GHS Program), which was launched in 2005 to aid in the international response to the Avian flu outbreak. Since its inception, the GHS Program has worked in collaboration with various partner countries and organizations to build and enhance the capacity of local, regional, and national entities to prevent the emergence of infectious disease threats and to mitigate the adverse effects of disease on local communities (USAID, 2024). Since the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, the USAID GHS Program has made an investment of $1.6 billion to aid in building countries’ capacity to address infectious disease outbreaks (USAID, 2024).

Global Vulnerability

The global response to the COVID-19 pandemic brought to light significant weaknesses in the ability for many communities and healthcare systems to effectively respond to a large-scale disease outbreak (Al Knawy et al. 2022). While all nations are impacted by disasters and public health emergencies, their infrastructures, resources and populations are impacted in different ways based on multiple factors, including their level of emergency response capacities and resilience. The impact of a disaster on a community is evaluated by the impact it has on the societal sectors and affected populations.

“Vulnerability” is a measure of the likelihood that an entity—e.g., region, population, individual—will be adversely impacted by exposure to a hazard, and “exposure” is the suggestion that an entity will experience the forces of the hazard (Coppola 2021). Another aspect of vulnerability is limiting coping capacity, which is often witnessed among certain populations when disasters occur. While the COVID-19 pandemic clearly showed us the global vulnerability to infectious disease as exposure to the virus increased, other key interactions of hazards and vulnerability are also important to consider.

Regardless of their origin, all disasters pose significant threats and challenges to societies. They disrupt normal life, often causing extensive loss of life and property. Economies can be severely affected, with some sectors suffering more than others. Disasters are typically evaluated by the degree to which they adversely affect human populations (Keller 2015; “Disaster Risk and Vulnerability: The Role and Impact of Population and Society” n.d.). Few sectors in a nation devastated by a disaster remain unscathed, including industry, human mobility, food and infrastructure, and in some cases, the risk of disaster is exacerbated by humanitarian crises and armed conflict (“Disaster Risk Reduction in Least Developed Countries” 2020). The environment, too, can sustain damage that takes years, if not decades, to heal. Understanding these impacts is not just important but crucial for devising effective disaster management strategies.

Situational and environmental factors can influence the scale, response, and recovery of a disaster. Industrialized cities hit by a tornado or hurricane, for instance, can result in mass displacement of the residents, chemical contamination of land and water, and significant environmental damage to infrastructure, community assets and sources of revenue that lead to widespread economic loss (Rebeeh et al. 2019). The causes of such events are numerous, and there are serious implications for institutions and individuals.

In his book, Fatal Isolation, which chronicles the events leading up to and during the 2003 heat wave in Paris, France, Keller encapsulates this relationship:

Yet the social, economic, and political contexts of disasters remain critical to their interpretation. Disasters are by definition social events, considered in light of their human impact, assessed in measures such as insured losses and mortality. Heat waves, droughts, floods, famines, and tsunamis originate in natural phenomena, but we interpret them through their effects on the local human environments with which they collide. When a hurricane is moving across the sea, it is a threat; when it strikes a community, it is a disaster. …Likewise, disasters’ effects have important social and political components; droughts, for example, lead to famine only in environments where relief mechanisms fail and when market effects draw food away from those who need it the most. (Keller 2015)

Because of the myriad ways in which disasters can negatively impact different sectors and industries within a geographic area, disasters undermine development and pre-existing efforts to build up the infrastructure of a community can be waylaid as bridges are washed away, crops are flooded, homes and businesses crumble and roads become impassible. At the same time, the vulnerability of an individual or population will affect the magnitude to which the hazard will be experienced. These relationships work together to shape the way the disaster is experienced by the individual or community and how it will ultimately impact the lives of the people involved.

In the case of the 2023 flooding in northeastern Libya, for instance, the residents’ risk of exposure to the mudslide was increased by the broken dams and floodwaters, while the extent of the disaster was severely intensified by the country’s political instability and poverty (Oduoye et al. 2024; UN News 2023). Likewise, the weakening of the infrastructure and healthcare system in West Africa as a result of the Ebola outbreak in 2014-2015 increased the vulnerability of the West African people to other infectious diseases during the following years, including malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS, resulting in increased mortality rates due to these diseases (Parpia et al. 2016).

The Pressure and Release (PAR) Model is a widely accepted conceptual model that expands these concepts and suggests a disaster occurs when the forces of a hazard interacts with one or more processes that create vulnerability in a population (Awal 2015). The model portrays three types of pressures that converge at a point of potential disaster: fundamental root causes, dynamic societal, socio-political and economic pressures, and people’s susceptibility to the negative impacts of a disaster, which includes precarious livelihoods and unsafe locations (Hammer et al. 2019; Awal 2015; Wisner, Gaillard, and Kelman 2015). The capacity of an individual or community is linked to the reduction of vulnerability, thereby setting up capacity-building as a mitigation measure for disaster preparedness (Wisner, Gaillard, and Kelman 2015).

Collaboration: Efforts Across Nations

Hazards and global vulnerability to disasters requires a unified international approach to disaster management and deliberate cooperation and clear communication in all stages of emergency planning, response, and recovery. The transnational nature of disasters and public health emergencies underscores the importance of this international collaboration, as they often involve and impact multiple countries. In the absence of such collaboration and communication, there is a risk of duplicating efforts or missing crucial response activities, leading to resource wastage and potentially higher rates of morbidity and mortality.

Moreover, the interconnectedness of our global community, spanning economies, ecosystems, and societies, intensifies the ripple effects of disasters occurring in one region on the rest of the world. As such, developing robust international cooperation is vital to our collective ability to manage disasters effectively. This involves sharing resources, knowledge, and best practices, and coordinating international response efforts. A key commitment for international cooperation is the swift rebuilding of basic infrastructure, especially in vulnerable areas. This includes the restoration of economic, financial, and healthcare systems, which is crucial in reestablishing these communities.

The 2004 tsunami in Southeast Asia, 2010 earthquake in Haiti, and recent COVID-19 pandemic serve as stark reminders of the enduring importance of international cooperation in disaster management. These events highlighted the need for swift response and recovery efforts, the challenges faced during disaster management, and the lessons learned for future disaster preparedness.

The communication and coordination of the fragmented Ebola response in West Africa in 2014-2015 would have benefited from a centralized command center utilized by the responding countries and organizations (Packard 2016). During the 2014-2015 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, NGOs in Guinea, Sierre Leone and Liberia were siloed and often duplicating efforts (Packard 2016). A joint response system promotes efficiency in the allocation of scarce resources, such as medications, vaccines, disaster responders and medical personnel. Similarly, relief organizations and volunteers could also be more efficiently mobilized through a jointly coordinated response system.

Many international humanitarian relief agencies recognize the need for a coordinated multinational disaster and public health emergency management network (“OCHA – United Nations” n.d.; “The Need for a Coordinated International Pandemic Response” 2020). Efficiency and cooperation are common characteristics of an effective disaster response that can significantly mitigate the detrimental effects of disasters on impacted populations. In practice, however, these efforts are often limited or missing and are not without their set of challenges. Political tensions, funding limitations, and logistical issues are just a few of the many obstacles that can impede these vital operations (Broussard et al. 2019). To overcome these hurdles, all involved members of the international community share responsibility in sustaining the cooperation of a joint disaster response.

Internationally accepted standards that outline best practices and procedures for disaster response and recovery practices would facilitate an effective and coordinated response across all involved jurisdictions. Similarly, a shared, real-time database managed and accessed by affected stakeholders would provide up-to-date information that could effectively inform decision-making processes. This shared database could also inform and support international partnerships for research and development of disaster management technologies.

A good example of sharing a real-time database for international disaster response is the International Charter Space and Major Disasters (Charter). The Charter is a program begun in 1999 by the European Space Agency, France’s Centre national d’études spatiales (CNES), and the Canada Space Agency. When asked for assistance by an affiliated agency, computer operators at the Charter select and send photographs taken of a disaster location by one or more of its 61 member satellites to assist with the agency’s response and recovery efforts (“The International Charter Space and Major Disasters” 2024). Note that there were 678 activations of the system between 2000 and 2020 within 126 countries.

Efforts to bridge disaster relief responses between countries have been initiated with the aim of providing mutual assistance in times of emergencies. Collaborations have been observed between nations and international organizations, such as the United Nations (UN) and the Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (USAID/OFDA). Collaborative agencies strive to bridge the gap between national and international emergency management capabilities and aim to enhance the effectiveness of emergency response and relief operations by working together to provide much-needed help to nations in crisis.

Challenges in International Cooperation

Those who manage disasters at the international level face continuous challenges. While there is a clear need for effective coordinated emergency management at an international level and although significant efforts have been made, there are considerable barriers to overcome, and involved organizations and nations have varying capacities to effectively respond to and recover from a public health emergency or disaster (De Ruiter et al. 2020). Cooperation between international agencies can be difficult, including the coordination of aid and capacity building among nations, resource limitations, and political barriers. Emergencies are unpredictable and reactions to them present complex challenges stemming from a variety of factors, including language barriers, political differences, the management of devastated disaster sites, and logistical issues (Corbin et al. 2021; Feng and Cui 2021; Makwana 2019). Efforts to provide humanitarian aid to a population entrenched in an armed conflict zone, for instance, are often hindered by various challenges, including limited resources, ethical dilemmas, and logistical complications (Broussard et al. 2019).

In some cases, the resilience of countries to infectious diseases and their ability to respond to an outbreak has been hampered by the lack of cooperation between governments and a dearth of technological tools that share relevant data (Zhang et al. 2023). Effective communication and information sharing in communities and between nations after disaster are critical components of recovery, and activities that promote health need to be adapted to fit the local needs of the community in crisis (Corbin et al. 2021).

Launching collaborative efforts for swift reconstruction of homes, roads, schools, and other essential infrastructure can ensure that affected communities can return to normalcy as soon as possible. An aid organization involving the community in resilience preparedness activities is key to successfully mobilizing and engaging at-risk communities (Corbin et al. 2021; Herstein et al. 2021). However, humanitarian agencies should be aware of the ethical implications of minimizing the risk of injury or illness to their own workers in a dangerous setting by transferring potentially dangerous tasks from the aid organization workers to local individuals (Broussard et al. 2019).

The aftermath of disasters often leaves a lasting economic and social impact on the affected individuals and communities (Makwana 2019). Therefore, disaster management strategies must also encompass post-disaster recovery and rebuilding efforts. This includes providing psychological support, rehabilitating displaced populations, rebuilding infrastructure, and restoring livelihoods. Ensuring that communities can return to normalcy as quickly as possible is not just about rebuilding what was lost, but also about building back better to enhance their resilience to future disasters. Enhancing the global standards for post-disaster rehabilitation and recovery should be improved, ensuring that affected communities receive the necessary support to recover fully from disasters. This includes all aspects of recovery, from physical reconstruction to socio-economic rehabilitation efforts.

Ethical Issues Intrinsic to International Emergency Management

Ethical and political issues often play a significant role in international disaster management. The ethical issues may include the equitable distribution of resources, respect for human rights and dignity during a disaster response and maintaining transparency and accountability in all operations. For example, during a disaster, resources must be allocated in a way that is determined to be ethical and fair, which can cause tension between affected individuals and populations and an emotional toll on those who must prioritize resource recipients. Developing relevant allocation guidelines before a disaster occurs and making them available to decision-makers can be instrumental in effective resource allocation (Persad, Wertheimer, and Emanuel 2009; Emanuel et al. 2020). Disaster management operations should therefore be transparent, and those involved should be held accountable for their actions to ensure that resources are used effectively and appropriately.

Political issues at the global level that can likewise impact international disaster management include conflicts between nations that hinder cooperative efforts, differing political systems and policies that complicate coordination, and the use of disaster relief as a tool for political gain. For example, a country might withhold aid or resources during a disaster due to political disagreements or conflicts with the affected nation. Furthermore, some governments may prioritize their own political interests over the needs of disaster-stricken communities. This can result in inadequate or delayed disaster response and recovery efforts. In some cases, disaster relief efforts may be used as a means to bolster a country’s international reputation or to gain political favor, rather than focusing solely on the needs of those affected by the disaster.

International aid organizations regularly face ethical challenges when balancing their responsibilities to the local community, which can be contractual or presumed, and the safety of their team members. An organization may feel the need to involve the community leaders in decision-making, for instance, while believing the need for “bunkerization,” controlled access to individuals in the community (Broussard et al. 2019). A community without sufficient resilience can become dependent on foreign aid after a disaster and development can either stall or proceed under the control of foreign entities, whether states, NGOs or military organizations. This dependency on entities outside the local jurisdiction can contribute to challenging ethical issues as the power to make decisions and funding are leveraged in the aftermath of a disaster.

Addressing these ethical and political issues is crucial in ensuring effective and fair international disaster management. This requires ongoing dialogue, cooperation, and commitment from all members of the international community.

Role of Technology in International Emergency Management

In the modern world, technology has become not just a useful tool but an essential component of international disaster management. It equips professionals in the field with the necessary tools for communication, disaster prediction and monitoring, data collection, and weather pattern analysis. Over time, technology has evolved and improved to the point where it now plays an indispensable role in the context of international disaster management. The use of artificial intelligence in disaster prediction and management and advanced communication technologies for timely alerts are especially promising developments.

As modern tools become more accurate, reliable, and cost-effective, innovative, technology-driven response activities are becoming an integral part of disaster management strategies. For example, predictive modeling uses data and algorithms to anticipate disasters and inform decision-making processes (Haggag et al. 2021; Zanchetta and Coulibaly 2020) and risk assessment involves identifying potential hazards and assessing their potential impact on populations (Ward et al. 2022).

The growing dependency on technology is particularly distinct in the area of crisis communication. The development and expansion of emergency communication systems at local, regional, and national levels have reshaped the way information is disseminated during disasters. These systems allow for rapid communication between international and interagency stakeholders, enabling a more coordinated and effective response during disasters.

As crisis communication systems have become more sophisticated, they have ushered in a new era of disaster prediction and monitoring systems, resulting in more accurate and timely emergency alerts for communities. These systems have been revolutionized by the use of advanced computer modeling and other innovative tools. Technologies in this field now offer the ability to anticipate potential emergencies and track their evolution and movement across geographic regions. This predictive power, combined with the capacity to monitor disasters in real time, forms an invaluable toolset for mitigating the impact of disasters and saving lives.

In addition to prediction and monitoring, data collection and analysis tools are crucial components in the decision-making process during disasters. These tools provide real-time information that allows decision-makers to initiate informed actions. They must be completely reliable and able to endure the harsh conditions common to emergency response settings (Lalone, Toups Dugas, and Semaan 2023). With accurate and timely data at their disposal, disaster management professionals can drastically improve the efficiency and effectiveness of response and recovery, leading to better outcomes and lessened impacts. The ability to predict, track, and analyze disasters through data and technological tools can dramatically improve our preparedness and ability to react effectively. However, this requires an investment of funding and resources in technical expertise, infrastructure and data management practices to ensure the effective use of these tools.

As disaster management technologies become more developed and refined, ethical considerations assume a greater importance. Power, decision-making, and funding can be tied to the point of access and control of the technology used in a disaster response and the recovery of a community. Technology can be a cause of disparity, and the role of technology in international emergency management can be both an ethical challenge and a critical factor in the efficient recovery and progress of a community after a disaster.

It is critical to ensure that technology-based interventions respect and uphold human rights. The sanctity of privacy for individuals must be ensured, especially for those who are unable to maintain their own privacy due to the circumstances of the disaster. As we continue to harness the power of technology in disaster management, it is our responsibility to do so in a way that is respectful of individual rights and dignity.

Interest is growing in the field of disaster management to investigate the numerous ways artificial intelligence (AI) can be incorporated into disaster risk prediction systems and incident management protocols. The development of a global framework for this integration could transform how we predict, prepare for, and respond to disasters. Applying technology-driven emergency response strategies like drone surveillance and AI-based data analysis could significantly enhance our capacity to respond to disasters promptly and effectively. As the problems of climate change become more prevalent and observed, artificial intelligence is a promising tool for addressing these problems in such ways as reducing energy pollution and improving both urban disaster reliance and agricultural productivity (Chen et al. 2023).

Leadership and Profession of Emergency Management

Facilitating effective international collaboration in response to disasters and addressing the challenges inherent in these collaborations requires effective and well-trained emergency management professionals and effective leadership. A far-reaching network of disaster management organizations that serve diverse populations across borders can provide an array of specialized assistance and expertise when disasters occur and, ideally, are well-equipped to be on site and functioning at a high level to assist local responders soon after the onset of a disaster. International disaster management frameworks provide consistent training and common points of reference when decisions are made regarding disasters that affect the populations and societal sectors of multiple countries.

Global Organizations

The global organizational network involved in preparing for, responding to, and assisting in the recovery from disasters is anchored by several key organizations. For example, the United Nations, headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland, plays a pivotal role in global preparedness and response activities. The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), in particular, coordinates disaster reduction and focuses on the strategic planning and implementation of measures intended to diminish the risk of threats. The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) provides humanitarian aid and support to individuals and communities adversely impacted by emergencies, especially by providing physical needs such as temporary shelter and food. The World Health Organization (WHO) is responsible for efforts that respond to and mitigate the effects of public health emergencies around the world, including pandemics.

International Disaster Management Frameworks

International agreements, such as the International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction, can play a key role in managing risk and reducing loss of life on a global scale. In 2005, for instance, at the World Conference on Disaster Reduction in Hyogo, Japan, participants adopted the Hyogo Framework for Action (HFA). The framework aimed to significantly reduce global disaster risk and burden from 2005 to 2015 (Olowu 2010; 2010). Although the HFA was ultimately replaced by the Sendai Framework, it paved the way for the development of international disaster risk reduction (DRR) strategies and policies that improved stakeholders’ abilities to assess risk and prepare for emergencies (UNDRR, n.d.). The HFA emphasized enhancing early warning systems, educating communities to foster resilience, mitigating risk factors, and improving emergency preparedness at all levels of government (UNDRR, n.d.).

HFA member states recognized, however, that despite some progress, overall exposure to hazards in both low- and high-income countries had increased more than vulnerability had decreased. The growth of risk factors had outpaced their reduction, leading to a shift in focus. This shift led to the implementation of the Sendai Framework in 2015, which focuses on managing and identifying risk (UNDRRb, n.d.). The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 was adopted at the Third UN World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction in Sendai City, Miyagi Prefecture, Japan. The framework proposed seven targets and four priorities to action designed to significantly reduce the risk of disasters, deaths and economic loss through the support of individuals, businesses, communities and nations over the course of 15 years (UNDRRb, n.d.).

Emergency Management Within Nations

Emergency managers who work within local communities are typically tasked with strengthening local capacities, including mitigation and planning, training and educational initiatives, enhancing infrastructure resilience, and empowering communities to manage disasters at the community and individual levels.

A municipal or organizational emergency manager may also be responsible for managing displaced populations during crises, whether short-term (such as in a shelter after a tornado) or long-term (such as in response to armed conflict in the region). Strengthening policies related to the management of displaced populations can ensure the protection and welfare of these vulnerable groups during times of crisis (Leaning and Guha-Sapir 2013).

Emergency managers may also need to advocate for psychological support and mental health services for affected populations during and after a disaster. Mental health is often overlooked during disaster response efforts, but providing psychological support services during and after disasters can be critical actions to help individuals cope with the traumas experienced

Emergency managers working at the community-level are key facilitators among agencies and responders during a disaster response. They are often among the first responders during a disaster and can assess the brunt of its impact. Empowering community members through knowledge sharing, resource allocation, and capacity building can significantly enhance the overall effectiveness of disaster response. Community-based disaster management strategies that involve local communities in planning, decision making, and implementation can lead to more sustainable and resilient disaster response mechanisms.

Preview of Chapters

With this complex context in mind, the following volume explores the unique issues surrounding the management of international disasters. The authors will present and analyze challenging problems related to public health emergencies and disasters resulting from natural hazards, evolving tools and technology developed to advance response and recovery activities, and the mitigation of disproportionately severe effects of disasters on vulnerable populations and communities.

Section I: Identifying the Context of Disasters and Emergency Management

The effective management of a multinational disaster requires a network of knowledgeable professionals to communicate and collaborate on emergency preparedness and recovery initiatives. The authors of the chapters in this section look at the context surrounding complex disasters and how it shapes humanitarian preparedness, response and recovery activities.

In Chapter 2, “Beyond Borders: Comparative Disaster Response Systems and the Challenges of Humanitarian Relief and Coordination,” Suarez examines the complexities of global disaster responses, highlighting the differences between the approaches used by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) in its response to the 2010 earthquake in Port-au-Prince, Haiti and the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) when it responded in 2017 to Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. Suarez aims to suggest solutions to common problems when responding to disasters that require international coordination.

Ayers, Chadburn and Hoque discuss the use of the innovative people-centered early warning systems (PC-EWSs) during the development and evolution of a disaster event in Chapter 3, entitled “Behaviourally-Informed Early Warning and Anticipatory Action: Unleashing the Potential of Locally-Led Pre-emptive Response and the Forecast-Based Financing it Requires.” The authors argue that these systems can be part of a new way to approach humanitarian relief that benefits vulnerable populations during a disaster.

Yang, the author of Chapter 4, “Evacuation Theories and Practices: Case Analysis in Taiwan,” looks at disaster response through the lens of evacuation protocols, applying a model developed by the author to assess the implementation of evacuation procedures in six communities in Tawain affected by mudslide and flooding. Yang focuses primarily on one of these communities and interviews local leaders to evaluate the use of information provided to the community, resources mobilization by responders and the collaboration between organizations during the response to the community’s mudslide.

In Chapter 5, entitled “Challenges in Preparing for and Responding to Disasters in Taiwan and the U.S.: Reflections from Practice and Academia,” Chang examines both the shared and diverse challenges of disaster preparation and response activities conducted in Taiwan and the U.S. The author uses his first-hand experience and research findings in both countries to inform recommendations for emergency responders in any country to overcome related challenges.

Section II: Becoming More Proactive

A proactive response to a disaster often requires a robust, multi-dimensional approach to preventing, mitigating and preparing for disasters. This approach can include infrastructure fortification measures that bolster the resilience of buildings and other structures against hazards. It may also involve capacity building activities that enhance the ability of individuals, communities, and organizations to effectively respond to and recover from disasters, promoting community resilience.

In Chapter 6, “Learning from Smong: Incorporating Local and Indigenous Knowledge in Disaster Management,” Sheach looks at the role that local and indigenous knowledge (LIK) plays in reducing disaster risk in a community. The author uses two different types of knowledge, metis and techne, to analyze indigenous and external knowledge and how they relate to disaster response and recovery.

Brenner, Mayberry, Kennedy and Anthonisen argue in Chapter 7, “Nations Among Nations: Strengthening Tribal Resilience and Disaster Response,” that indigenous populations disproportionately experience the impact of disasters compared to other local jurisdictions, and legal and policy issues can increase the complexity of a disaster response. The authors glean insights from conversations with members of Tribal Nations in the U.S. to suggest ways in which more resilient indigenous communities can be built and how to manage international boundaries in settings with multiple government jurisdictions.

Murphy, Chretien, Gunson and Brown contend in Chapter 8, “Rural Critical Infrastructure and Emergency Management Planning to Improve Climate Change Resilience: Insights from Rural Ontario, Canada,” that municipal emergency management planners do not take sufficient consideration of climate change. The authors suggest ways in which communities could be better prepared for extreme weather events by addressing and responding to climate-related factors.

Section III: Addressing the Needs of the Vulnerable

Vulnerable populations, including children, elderly individuals, persons with disabilities, and economically disadvantaged communities, often suffer the most during disasters (Benevolenza and DeRigne 2019; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2015; Fatemi et al. 2017). Addressing their needs is of upmost importance and emergency responders and managers should ensure that their disaster response protocols, equipment and facilities are equipped to provide these vulnerable populations with the necessary aid and support (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2015). This involves creating inclusive disaster response strategies that consider the unique needs and challenges of each population at risk.

In Chapter 9, “Disability Inclusive Disaster Risk Reduction (DiDRR) in South Asia: Status, Prospects, and Challenges,” Islam, Farid, Roberts and Glick explore the current status of disaster preparedness and resilience efforts in South Asian countries to support the unique needs of people with disabilities in disasters, highlighting trends and lessons learned.

Raj, Schneider, Latner, Baron and Burke – the authors of Chapter 10, “Pediatric Priorities Through the Disaster Management Cycle: Integrating Children’s Needs in Mitigation, Preparedness, Response and Recovery” – focus on the need for disaster planning strategies that center on the unique needs of children and families. The authors analyze the pervasive military-styled, resources-approach to managing disasters and suggest ways in which communities can benefit from a shift to an approach that focuses instead on the mental and physical health of individuals and utilizes resources provided by community-based organizations.

Prasad and Russell further explore the added value of the contribution by local organizations to a disaster response in Chapter 11, “Issues for Infant and Toddler Feeding at Disaster Mass Care Sites: Paradigm Shifts for Strategic and Operational Planning.” The authors argue for change in policies and procedures that direct the approach used by emergency responders to feed young children and the critical role emergency planners play in setting up effective protocols that will maintain the health of children during and after a crisis.

Aydiner, Hoban, Corbin and Gerber-Chavez close out this section by analyzing Germany’s recent responses to Ukrainian refugees and Turkish asylum seekers in Chapter 12, “Migrant Displacement in Conflicts: Emergency Management Response to Ukrainian Refugees and Turkish Asylum Seekers in Germany.” The authors examine the challenges faced by authorities to integrate displaced persons into the local communities and the skills required to interact with them effectively.

Section IV: Acknowledging and Addressing Challenges and Opportunities

The current landscape of addressing global disasters presents new opportunities and challenges. The increasing frequency and intensity of disasters, coupled with advancements in technology and communication, offers unprecedented potential for improving disaster response (Zanchetta and Coulibaly 2020; Al Knawy et al. 2022). However, these advancements also pose new challenges that need to be addressed, such as increasing disparity in access to technology, cybersecurity threats, and data privacy concerns (Chen et al. 2023; Wirtz et al. 2014).

Feldmann-Jensen and O’Sullivan evaluate lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic and analyze the complexity of infectious disease disasters (ID disasters) in Chapter 13, “Lessons Learned from Key 21st Century Infectious Disease Outbreaks: Informing Future Risk Management Adaptation.” Through their analyses of recent case studies, the authors look at the impact of factors such as climate change and migration on the increased frequency of ID disasters and the subsequent social and economic outcomes.

During a crisis, governmental officials often exercise expanded powers and limit the fundamental autonomy of the people to mitigate adverse outcomes. In Chapter 14, “Return of the ‘Administrative State?’ The Expansion of Executive Power under Crisis,” Tso investigates the retention of expanded power by leaders after a national crisis and its potential impact on future political frameworks in a community or nation. The author highlights concrete cases during the COVID-19 pandemic and ways in which the broadened powers shaped the shifting perspective of the people toward governmental and health leadership.

In Chapter 15, “Technology in Emergency Management: A Review from Developed Nations with Considerations in a Global Context,” authors Cawley and McEntire explore the evolving role of technology over the past 20 years. They provide a comprehensive overview of the emergency management field and how it has been both transformed and challenged by technology integration. Reflecting on the history and current state of technology use in disaster preparedness and response, the authors propose recommendations for future practices and policies.

Lin and Tso, authors of Chapter 16, “Applications and Prospects of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Emergency Situations: A Case Study from Taiwan,” further develops the discussion surrounding technology by closely examining the operational and ethical aspects of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and the legislation that has been introduced to manage the use of UAVs. In particular, the authors look at the ways in which UAVs have been utilized to assess the extent of damage after a disaster and compare how regulations in Taiwan and European Union countries have been implemented to protect individuals during the collection of personal data.

Section V: Improving Professionalism in Emergency Management

Improving the skills of emergency managers and enhancing the professionalism of emergency management as a field is crucial to overcoming the challenges and leveraging the opportunities encountered when managing a disaster. This involves investing in the emergency managers’ training and development to ensure they are equipped with the necessary skills and knowledge to navigate the complex landscape of disasters, whether local or global. It also means fostering a culture of professionalism and accountability in emergency management, which is essential for ensuring effective and efficient disaster response.

In the first chapter of this section, Chapter 17, “Description of the Typical Emergency Manager: An Assessment of Who Leads in Times of Disaster,” Lavaris describes the essential qualities needed in an emergency manager to adequately address the challenges of current emerging issues in the chapter. In this chapter, Lavarias outlines the unique, specialized knowledge base and skillset required by an emergency manager to effectively respond to an emergency.

Richardson, McDuffie and Cooper, authors of Chapter 18, “The Capable Emergency Management Professional: Emerging Competencies for a Changing World,” argue that in this time of increasing complexity of disaster events and risk of emerging issues across the international emergency management landscape, communities are being negatively impacted by a lack of cohesive structure within the responding organizations that result in ineffective responses to emergency events.

In Chapter 19, entitled, “Credentialing and Professionalization in Emergency, Crisis and Disaster Management,” Ainsworth and Jones identify various pathways used to become a practicing professional in emergency, crisis and disaster management (ECDM). The authors review and analyze the efficiency and comprehensiveness of credentialing mechanisms provided by international jurisdictions as they align with specific criteria within ECDM.

Ferreria continues the examination of standardization in the professionalism of emergency management practitioners in Chapter 20, “Aligning International Strategy to Standards in Emergency Management: Current & Emerging Issues.” In this chapter, the author argues that confusion and inconsistency in professional standards for emergency management professionals has strengthened the effects of politicization and crises on disaster management, undermining the intentional decision-making of professionals that could reduce the risk of harm and improve community resilience.

This section concludes with an overview by Jones and Ainsworth of the need for crisis leaders to maintain consistent messaging and effective engagement with the community in Chapter 21, “The Challenges to a Modern Approach to Leadership, Management, Critical Thinking, and Decision Making Within an Emergency Management Environment.” The authors contend that as the international disaster community faces the ever-increasing pressure of evolving changes in the climate, data management, technological tools, and interpersonal leadership, fostering the positive involvement and perceived agency of individuals become a critical responsibility of crisis leaders.

Conclusion

As the reader explores the chapters that follow, the context of global disasters – including the complex and challenging landscape – should be kept in mind. However, by acknowledging the benefit of proactive approaches, addressing the needs of vulnerable communities and populations, leveraging new opportunities to learn from each disaster and bolster capacities, improving emergency management strategies, and focusing on post-disaster recovery, we can make significant strides in mitigating the impact of these disasters and enhancing our collective resilience.

Managing disasters on a global scale is thus a vital aspect of global cooperation in the face of adversity. Despite the challenges it faces, its importance is increasingly recognized, aided by advancements in technology and a growing emphasis on global partnerships. As we move forward, it is crucial that the international community continues to strengthen these efforts to safeguard our shared world. International disaster management is a complex field necessitating global cooperation and coordination. While challenges persist, the future holds promise with advancements in technology, increased international cooperation, and a focus on strengthening local capacities.

This underscores the urgent need for concerted global action to mitigate the effects of climate change and build resilience against these increasingly common events. We must work together as a global community to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, protect vulnerable communities, and develop strategies to adapt to our changing climate. These events can have devastating impacts on both human life and the environment, creating a cycle of destruction that threatens to continue if significant action is not taken.

Future of International Disaster Management

The ability to effectively handle future global disasters and mitigate their adverse effects on communities relies on such endeavors as strengthening the profession of emergency management and developing robust local capacities to respond to crises. Building stronger disaster response networks and sharing resources and expertise can enhance international cooperation and proactively prepare communities to withstand future disasters. Furthermore, empowering communities through training, education, and infrastructure resilience can strengthen local capacities for disaster management, especially when the needs of vulnerable populations are considered and addressed.

Looking ahead, the future of international disaster management is likely to be shaped by many evolving factors and thus requires continuous assessment and attention. The increasing importance of climate change suggests a greater frequency and intensity of seismic and extreme weather events. Technological advancements promise improved prediction, response, and recovery capabilities. Strengthening global partnerships is therefore essential to fostering cooperation and resource-sharing in the face of global emergencies.

References

Al Jazeera. 2024. “Rival Governments Cooperate to Aid Libya’s Flood Victims as Misery Piles on.” Al Jazeera. 2024. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/9/14/rival-governments-cooperate-to-aid-libyas-flood-victims-as-misery-piles-on.

Al Knawy, Bandar, Mollie Marian McKillop, Joud Abduljawad, Sasu Tarkoma, Mahmood Adil, Louise Schaper, Adam Chee, et al. 2022. “Successfully Implementing Digital Health to Ensure Future Global Health Security During Pandemics: A Consensus Statement.” JAMA Network Open 5 (2): e220214. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.0214.

“Animal Agrocrime and Agroterrorism.” n.d. Accessed July 13, 2024. https://www.interpol.int/en/Crimes/Terrorism/Bioterrorism/Animal-agrocrime-and-agroterrorism.

Arab Center Washington. 2023. “Libya: Despite Talks on a Unified Government, Impasse Remains.” Arab Center Washington DC. June 13, 2023. https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/libya-despite-talks-on-a-unified-government-impasse-remains/.

Awal, M A. 2015. “Vulnerability to Disaster: Pressure and Release Model for Climate Change Hazards in Bangladesh.” International Journal of Environmental Monitoring and Protection 2 (2): 15–21.

Benevolenza, Mia A., and LeaAnne DeRigne. 2019. “The Impact of Climate Change and Natural Disasters on Vulnerable Populations: A Systematic Review of Literature.” Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 29 (2): 266–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2018.1527739.

Broussard, Grant, Leonard S. Rubenstein, Courtland Robinson, Wasim Maziak, Sappho Z. Gilbert, and Matthew DeCamp. 2019. “Challenges to Ethical Obligations and Humanitarian Principles in Conflict Settings: A Systematic Review.” Journal of International Humanitarian Action 4 (1): 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41018-019-0063-x.

Center for Disaster Philanthropy. 2024. “2023 Libya Floods.” Center for Disaster Philanthropy. April 12, 2024. https://disasterphilanthropy.org/disasters/2023-libya-floods/.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. 2015. “Planning for an Emergency: Strategies for Identifying and Engaging At-Risk Groups.”

Chen, Lin, Zhonghao Chen, Yubing Zhang, Yunfei Liu, Ahmed I. Osman, Mohamed Farghali, Jianmin Hua, et al. 2023. “Artificial Intelligence-Based Solutions for Climate Change: A Review.” Environmental Chemistry Letters 21 (5): 2525–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10311-023-01617-y.

Coppola, Damon. 2021. Introduction to International Disaster Management. Fourth. Philadelphia: Elsevier, Inc.

Corbin, J Hope, Ukam Ebe Oyene, Erma Manoncourt, Hans Onya, Metrine Kwamboka, Mary Amuyunzu-Nyamongo, Kristine Sørensen, et al. 2021. “A Health Promotion Approach to Emergency Management: Effective Community Engagement Strategies from Five Cases.” Health Promotion International 36 (Supplement_1): i24–38. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daab152.

“Disaster Risk and Vulnerability: The Role and Impact of Population and Society.” n.d. PRB. Accessed June 20, 2024. https://www.prb.org/resources/disaster-risk/.

“Disaster Risk Reduction in Least Developed Countries.” 2020. July 31, 2020. http://www.undrr.org/implementing-sendai-framework/sendai-framework-action/disaster-risk-reduction-least-developed-countries.

“Ebola Outbreak 2014-2016 – West Africa.” n.d. Accessed July 13, 2024. https://www.who.int/emergencies/situations/ebola-outbreak-2014-2016-West-Africa.

Emanuel, Ezekiel J., Govind Persad, Ross Upshur, Beatriz Thome, Michael Parker, Aaron Glickman, Cathy Zhang, Connor Boyle, Maxwell Smith, and James P. Phillips. 2020. “Fair Allocation of Scarce Medical Resources in the Time of Covid-19.” New England Journal of Medicine 382 (21): 2049–55. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsb2005114.

Environment, U. N. 2023. “Climate Change and Water-Related Disasters.” UNEP – UN Environment Programme. November 16, 2023. http://www.unep.org/topics/fresh-water/disasters-and-climate-change/climate-change-and-water-related-disasters.

European Commission. 2023. “8 Crises the World Must Not Look Away from in 2024.” 2023. https://civil-protection-humanitarian-aid.ec.europa.eu/news-stories/stories/8-crises-world-must-not-look-away-2024_en.

———. 2023b. “Libya Floods: Tackling a Complex Emergency.” 2023b. https://civil-protection-humanitarian-aid.ec.europa.eu/news-stories/stories/libya-floods-tackling-complex-emergency_en.

Fatemi, Farin, Ali Ardalan, Benigno Aguirre, Nabiollah Mansouri, and Iraj Mohammadfam. 2017. “Social Vulnerability Indicators in Disasters: Findings from a Systematic Review.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 22 (June):219–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2016.09.006.

Feng, Yi, and Shaoze Cui. 2021. “A Review of Emergency Response in Disasters: Present and Future Perspectives.” Natural Hazards 105 (1): 1109–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-020-04297-x.

Haggag, May, Ahmad S. Siam, Wael El-Dakhakhni, Paulin Coulibaly, and Elkafi Hassini. 2021. “A Deep Learning Model for Predicting Climate-Induced Disasters.” Natural Hazards 107 (1): 1009–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-021-04620-0.

Hammer, Charlotte Christiane, Julii Brainard, Alexandria Innes, and Paul R. Hunter. 2019. “(Re-) Conceptualising Vulnerability as a Part of Risk in Global Health Emergency Response: Updating the Pressure and Release Model for Global Health Emergencies.” Emerging Themes in Epidemiology 16 (1): 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12982-019-0084-3.

Herstein, Jocelyn J., Michelle M. Schwedhelm, Angela Vasa, Paul D. Biddinger, and Angela L. Hewlett. 2021. “Emergency Preparedness: What Is the Future?” Antimicrobial Stewardship & Healthcare Epidemiology 1 (1): e29. https://doi.org/10.1017/ash.2021.190.

Htway, Zin, and Cassandra Casteel. 2015. “Public Health Leadership in a Crisis: Themes from the Literature.”

International Medical Corps. 2024. “International Medical Corps: First There, No Matter Where.” International Medical Corps. 2024. https://internationalmedicalcorps.org/.

Keller, Richard C. 2015. Fatal Isolation: The Devastating Paris Heat Wave of 2003. Chicago: the University of Chicago press.

Kharb, Aditi, Sandesh Bhandari, Maria Moitinho De Almeida, Rafael Castro Delgado, Pedro Arcos González, and Sandy Tubeuf. 2022. “Valuing Human Impact of Natural Disasters: A Review of Methods.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (18): 11486. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811486.

Lalone, Nicolas, Phoebe Toups Dugas, and Bryan Semaan. 2023. “The Technology Crisis in US-Based Emergency Management: Toward a Well-Connected Future.” In . https://doi.org/10.24251/HICSS.2023.226.

Lawton, Luke. 2013. “Public Health and Crisis Leadership in the 21st Century.” Perspectives in Public Health 133 (3): 144–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913913488469.

Leaning, Jennifer, and Debarati Guha-Sapir. 2013. “Natural Disasters, Armed Conflict, and Public Health.” New England Journal of Medicine 369 (19): 1836–42. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1109877.

Makwana, Nikunj. 2019. “Disaster and Its Impact on Mental Health: A Narrative Review.” Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 8 (10): 3090. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_893_19.

NASA. 2024. “Extreme Weather – NASA Science.” 2024. https://science.nasa.gov/climate-change/extreme-weather/.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association [NOAA]. 2023. “2023 U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters in Historical Context | NOAA Climate.Gov.” January 8, 2024. https://www.climate.gov/media/15782

———. n.d. “Threats to Habitat | NOAA Fisheries.” n.d. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/insight/threats-habitat.

“OCHA – United Nations.” n.d. Accessed March 13, 2024. https://asiadisasterguide.unocha.org/IV-international-coordination.html.

Oduoye, Malik O., Karim A. Karim, Mayowa O. Kareem, Aminu Shehu, Usman A. Oyeleke, Habiba Zafar, Muhammad Muhsin Umar, Hafsa A.A. Raja, and Abdullahi A. Adegoke. 2024. “Flooding in Libya amid an Economic Crisis: What Went Wrong?” International Journal of Surgery: Global Health 7 (1). https://doi.org/10.1097/GH9.0000000000000401.

Olowu, Dejo. 2010. “The Hyogo Framework for Action and Its Implications for Disaster Management and Reduction in Africa.” Jamba : Journal of Disaster Risk Studies 3 (1): 303–20. https://doi.org/10.10520/EJC51181.

Packard, Randall M. 2016. A History of Global Health: Interventions into the Lives of Other Peoples. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins university press.

Parpia, Alyssa S., Martial L. Ndeffo-Mbah, Natasha S. Wenzel, and Alison P. Galvani. 2016. “Effects of Response to 2014–2015 Ebola Outbreak on Deaths from Malaria, HIV/AIDS, and Tuberculosis, West Africa.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 22 (3): 433–41. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2203.150977.

Persad, Govind, Alan Wertheimer, and Ezekiel J Emanuel. 2009. “Principles for Allocation of Scarce Medical Interventions.” The Lancet 373 (9661): 423–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60137-9.

Ravi, Sanjana J., Kelsey Lane Warmbrod, Lucia Mullen, Diane Meyer, Elizabeth Cameron, Jessica Bell, Priya Bapat, et al. 2020. “The Value Proposition of the Global Health Security Index.” BMJ Global Health 5 (10): e003648. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003648.

Rebeeh, Yousif A. M. A., Shaligram Pokharel, Galal M. M. Abdella, and Abdelmagid S. Hammuda. 2019. “Disaster Management in Industrial Areas: Perspectives, Challenges and Future Research.” Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management 12 (1): 133–53. https://doi.org/10.3926/jiem.2663.

Reuters. 2023. “Foreign Offers of Aid in Response to Libya’s Floods.” Reuters, September 13, 2023, sec. Africa. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/foreign-offers-aid-response-libyas-floods-2023-09-13/.

Semenza, Jan C., Elisabet Lindgren, Laszlo Balkanyi, Laura Espinosa, My S. Almqvist, Pasi Penttinen, and Joacim Rocklöv. 2016. “Determinants and Drivers of Infectious Disease Threat Events in Europe.” Emerging Infectious Diseases 22 (4): 581–89. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2204.151073.

Smith, Adam B. 2020. “U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters, 1980 – Present (NCEI Accession 0209268).” NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. https://doi.org/10.25921/STKW-7W73.

“The 2021 Global Health Security Index.” n.d. GHS Index. Accessed July 13, 2024. https://ghsindex.org/.

“The International Charter Space and Major Disasters.” 2024. 2024. https://disasterscharter.org/web/guest/home;jsessionid=C66E9489D940C329A3FDCC3BB2A2FF4F.APP1.

“The Need for a Coordinated International Pandemic Response.” 2020. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 98 (6): 378–79. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.20.020620.

UN News. 2023. “Libya: Humanitarian Response Ramps up as Floods of ‘epic Proportions’ Leave Thousands Dead.” September 12, 2023. https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/09/1140652.

UNDRR. 2020. “The Human Cost of Disasters: An Overview of the Last 20 Years (2000-2019) | UNDRR.” October 12, 2020. http://www.undrr.org/publication/human-cost-disasters-overview-last-20-years-2000-2019.

UNICEF. 2023. “Devastating Floods in Libya | UNICEF.” 2023. https://www.unicef.org/emergencies/devastating-flooding-libya.

USAID. 2024. “Libya | Humanitarian Assistance.” U.S. Agency for International Development. July 3, 2024. https://www.usaid.gov/humanitarian-assistance/libya.

Ward, Philip J., James Daniell, Melanie Duncan, Anna Dunne, Cédric Hananel, Stefan Hochrainer-Stigler, Annegien Tijssen, et al. 2022. “Invited Perspectives: A Research Agenda towards Disaster Risk Management Pathways in Multi-(Hazard-)Risk Assessment.” Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 22 (4): 1487–97. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-22-1487-2022.

“Wildfire Climate Connection | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.” n.d. Accessed June 11, 2024. https://www.noaa.gov/noaa-wildfire/wildfire-climate-connection.