17 The Capable Emergency Management Professional: Emerging Competencies for a Changing World

Kesley J. Richardson, DPA, MPH, CEM®; Joshua D. McDuffie, M.S., E.I.; and Terry D. Cooper, DHSc, MS, MPH, CEM®

Authors

Kesley J. Richardson, DPA, MPH, CEM®, MEM-S, Loyola University

Joshua D. McDuffie, MS, E.I., Vanderbilt University

Terry D. Cooper, DHSc, MS, MPH, CEM®, University of New Haven

Keywords

Emergency Management, Interprofessional Education, Governance, Competencies

Abstract

The increasingly complex risks associated with emergent issues in emergency management, compounded with problems existing in organizational structures, are beginning to outpace the institutional ability to address them, leading to more significant losses and damages in several communities. The responsibilities of emergency management agencies continue to expand, and many may need more resources and knowledge to address them. This chapter will survey the literature to highlight what will be discussed as the critical competencies of the everyday emergency manager from an international paradigm. We approach this by across governance structures. In our discussion, we cover various topics ranging from current higher education programs, certifications (by state, country, and international), and the gaps identified by emergency managers internationally. The ability of emergency management professionals to adequately meet a standard level of performance has far-reaching implications for community resilience, engagement, and trust. It can also close the performance gap by applying leadership, management, critical thinking, and decision-making strategies.

Introduction

What is a capable emergency management (EM) professional? Is it the practitioner with the first responder experience from spending years with the fire department, law enforcement office, or military? Or is it a person with post-secondary education who is focused on the principles and policy that emergency management has to offer? Here, we clarify this discussion regardless of how you view emergency management.

Foremost, the terms emergency manager, professional and capable, are worth defining. The National Fire Protection Agency (NFPA) 1600 defines an emergency manager as the individual who manages the “ongoing process to prevent, mitigate, prepare for, respond to, maintain continuity during, and to recover from, an incident that threatens life, property, operations, or the environment (Spiewak, 2014). Simply put, emergency managers help create and maintain the framework necessary to reduce vulnerability in a community. Maintaining structure, functionality, and relationships among stakeholders differentiates them from emergency responders, who focus on taking strategic actions within the framework and responding to specific hazards as they arise (Hubbard, 2021).

The term “professional” has developed over time and coincided with the development of what a profession is. Definitions have typically included the following criteria: provision of a vital public service, significant requirements for education and training, adherence to an ethical code, a defined scope for autonomy within the practice, and self-regulation (Billett et al., 2014). Spiewak, 2014 notes that professions have “a common body of knowledge; specialized education and training; benchmarked performance standards; continuing professional development; professional association” and relevant social traits that build positive relationships.

When the term “capable” is used in the context of a person occupying a role, it usually refers to one having the “required skills for an acceptable level of performance.” So, gathering these concepts together to form a unified understanding of the term, the capable emergency management professional operates and continually develops skills within a specialized body of knowledge and supports the maintenance of hazard reduction frameworks. An emergency manager may be a capable emergency management professional, but a competent emergency manager professional need not be an emergency manager.

In this chapter, we will propose a set of characteristics that we will define as critical capabilities for the modern emergency manager. This chapter will highlight not only the capabilities needed for the professional but also address the challenges from governance structures in an international context —which can often present barriers that limit a capable practitioner from performing their job—. The established requirements baseline will be discussed based on current emergency management literature and the recommendations for equipping the modern EM professional moving forward. Furthermore, we will propose that as risk, climate variability, and incident stabilization become more complex, the professional needs policy support, education, training, experience, and a system to support the development of more standardized practitioners globally. Such a system will support the prioritization of life safety, protection of property, and incident stabilization (FEMA, 2013). Finally, as current professionals try to mitigate scope creep, we discuss the implications of addressing these capabilities and deficiencies.

The current state of the standard EM, a professional, depends on the role and the type of government the professional works within, and there is a considerable level of international variance. Governance can be defined here as “steering and co-ordination of interdependent (usually collective) actors based on institutionalized rule systems (Benz, 2004, p. 25).” and reflects a change in the nature of a state. Succinctly put, governance manages the behaviors of social actors. An emergency manager is thus subject to the type of governance within their domain, whether the regulations are legally binding or societal norms (soft law) (Treib et al., 2007). Whereas an emergency manager operating under rigid forms of governance may favor policies as a vehicle for program implementation, the same emergency manager operating under weak governance may find more success focusing on relationships with local leaders and community groups. The emergency manager should be equipped for both, but we must acknowledge that circumstances often dictate a successful leader’s characteristics. The emergency manager professional, whether or not the title of an emergency manager is held, is subject to demands and legal structures. As is the case with variations in government types, the functions of the emergency manager, as understood in the U.S., may also be present in roles such as a Crisis Manager or Civil Defense Minister. We will highlight more of this in Section 1.

Section 2 will discuss the similar requirements for the capable emergency manager that arise independent of the governance structures and cultural norms, asking the question: What skills are transferable across all dimensions? Risks and hazards emerge from all corners of society, fueled by technological advancements, political unrest, and ecological degradation. How does the emergency manager develop capabilities to address what is increasingly becoming a “wave of risk” that the job description did not account for? We will draw from existing discussions related to competencies, highlighting the work of authors like Feldmann-Jensen, Jensen, and Smith, who developed guidance through their work on The Next Generation Core Competencies (NGCC) for Emergency Management Professionals and highlighted the benefits of technological, scientific, geographic, sociocultural, and systems literacy (Feldmann-Jensen, 2017). This document will be juxtaposed with other discussions on competencies in the literature to help identify convergence and divergence points within the relevant knowledge bodies.

Section 3 addresses current methods for training and educating the emergency management professional. As the emerging EM develops, it is trending towards adding incoming professionals with higher degrees of educational attainment and significantly diverse career backgrounds, which may require restructuring how training and education are done. The qualifications for a modern emergency manager must reflect the goals for the field moving forward rather than the time of the field’s inception. In an increasingly polarized and diffuse world, soft skills like risk communication and cross-disciplinary knowledge are linchpins in an effective EM action plan. The educational and experiential requirements for a capable emergency manager are also discussed.

Methodology

The methodological approach to this chapter utilized a scoping literature review / PRISMA model. The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) model is a filtering process for literature reviews that breaks down a large arrangement of articles in a reproducible way (PRISMA, 2020). Articles were initially gathered using relevant keywords. Examples of phrases used to search databases include “international governance systems,” “international emergency management,” “emergency management competencies,” “emergency management professional,” etc. A total of 63 articles passed the filtering stages and were deemed suitable for the scope of the discussion. Comparative analysis was also used throughout the chapter to juxtapose the varying roles of EM professionals within governance structures and the associated competencies that are required to operate successfully. The lack of comparable international emergency management literature limited the development of this chapter.

Literature Review

Section 1: The Emergency Manager’s Role Through the Lens of Governance Systems

Classification was done via government types that oversee their operations to organize the international context of emergency management worldwide. For example, in the U.S., the structure for coordinating interagency operations is organized via Emergency Support Functions (ESFs). This structure has advantages and disadvantages. One advantage is grouping interdisciplinary functions by categories (e.g., ESF 6 – Mass Care). A disadvantage is that the categories are not always exclusive; some functions may be multi-functional or operate in various ESFs (Yeskey, 1994). Other approaches included grouping by geographical regions, global economic status, and climate zones. Upon consideration, the governance approach represents an ideal grouping due to the significant influence that the rule of law and the operational capacity of the state play in determining the emergency manager’s role and scope of work. Indeed, there is variance even within governance types, but a general overview will serve the purposes of this manuscript. The government forms reviewed are democratic, monarchical, and single-party governments. This review will highlight the operational capacity of emergency management professionals internationally.

Democratic Governance

The democratic governance structure encompasses all systems where public elections determine the rule of law. This plays out as either a direct democracy, representative democracy, or parliamentary democracy. In the latter two, officials are elected and act in place of the people, while direct democracies form policy without a proxy. Some systems have constitutions (e.g., the U.S., Canada, and New Zealand), while others do not (e.g., Israel). The differences amongst these systems manifest when comparing the amount of legislation devoted to guiding emergency functions. The United States is an example of a representative democracy that has housed its emergency management functions in a uniquely organized bureaucratic system that offers considerable autonomy and resources to its departments. As of 2006, FEMA has been established as an independent executive agency within the Department of Homeland Security, allowing the director to serve as an advisor to the president. Even with FEMA as the federal entity for American emergency management, the practices and principles are not uniformly applied. FEMA can dictate models, powers, and processes at a federal level (the highest level within the American government). Still, states can have statutes with different definitions and roles for the state-level emergency management agency. For example, in Florida’s statutes, chapter 252 outlines all emergency management powers (The 2023 Florida Statutes, 2024). State statutes define emergency management powers, and these differences are on par with the differences of neighboring countries. For example, the policy differences between Florida and Georgia may vary in the same way that policies vary between countries like France and Germany. Emergency declarations can also shape governance. Crises have changed how democratic nations distribute emergency powers, with 9/11’s effect on emergency management being a prominent example in the United States.

Australia stands out as a peer, both as a federal and democratic nation, whose structure allows for more coordination amongst states, territories, and the federal government. The Council of Australian Governments, which served as a forum for state and territory collaboration with Parliament, allowed for the development of reforms through consensus of its members. The benefits and drawbacks to this arrangement became evident during the nation’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, as an intergovernmental forum allowed for comparatively more coordinated responses than the U.S. (Downey & Myers, 2020). Any relative success for this approach requires significant time spent building procedures. If procedures are not well established, this can suffer from delayed action resulting from a lack of consensus. This structure has since been replaced with a National Cabinet, where representatives from different states and territories are more integrated into the government, and their deliberations are more transparent.

What does this mean for the emergency manager in a democratic governance system? The systems that govern the scope and responsibilities associated with their role are subject to varying degrees of authority and delegation. As an example, in response to increasingly complex and severe emergencies, several states have elevated emergency management agencies to a standalone role (Overly, 2022), indicative of the increasing responsibilities the agencies are taking on. Within this chapter, an agency is defined as “a permanent or semi-permanent organization” connected to a level of government. Democratic governance provides public services to a jurisdiction (University of the District of Columbia. n.d). It is important to note that even when there is a delegation of authority, the elected official’s responsibility for the community or jurisdiction still falls, even as the practitioner serves as the decision-maker or incident manager. For example, in Florida, title XVII chapter 252 from 252.31 to 252.71 expresses the extent of emergency management powers (Florida Legislature, 2024). This statute empowers the agency to take emergency management actions but may or may not associate responsibility for those actions. The practitioner serves as a proxy and is given the authority to make a strong recommendation, but their decisions are still subject to leadership at the state level. The democratic governance structures for emergency management professionals and practitioners are more of a reflection within a FAMA context.

Monarchal Governance

Monarchal governance refers to governance systems headed by a single ruler and based upon an undivided sovereignty of rule from the royal family. This reflects areas in Europe (e.g., the United Kingdom) with a long history of monarchical governance and regions with more modern monarchies. Rulership was often associated with belief systems that held to the principle of a “divine right” to rule. However, many of these countries have made significant structural changes to modernize this form of governance (O’Brian, 2005). The responsibility of modernizing the forms of governance within a monarchical government initially falls to the ruling class but can be delegated depending on the adopted modern structures. The degree of delegation distinguishes an absolute monarchy from a more modern constitutional monarchy. These institutions, like all forms of government, often have wicked problems around accountability despite enabling actions to perform disaster-related actions for emergency management professionals and managers. Countries like Saudi Arabia or Brunei have fewer restrictions on a monarch’s ability to influence law, compared to areas like the United Kingdom and Japan, where there is little that a monarch can do of their own accord.

Emergency Management in the latter nations focuses on organizational resilience, adapting disaster governance structures and collaboration practices to the needs of the locales being served. As a result, local (municipal) governments have more flexibility in configuring emergency management procedures, as in Japan (Kato et al., 2022). In Japan’s case, the municipalities are required to design plans; Saudi Arabia, by comparison, is a country where the monarch is more invested in governance. Saudi Arabia has a General Directorate of Civil Defense that is instituted by royal decree and tasked with overseeing “protocols and operations required to protect civilians as well as public and private properties from the dangers of fires, natural disasters, wars, and other accidents…rescuing those afflicted by such catastrophes, ensuring transportation safety, and protecting national resources in times of peace and emergency” (Alamri, 2010).

The development of such a program is dependent on royal decree. Saudi Arabia has seen two significant restructurings, consolidating fire and security into civil defense in 1965 and then modifying the organizational structure in 1987. There is a board appointed by the ruler, executive committees to oversee different sectors and a pool of volunteers that resembles the role of FEMA reservists. Compare this with the United Kingdom, where there is no formal department for emergency management, but there are roles laid out in the Civil Contingencies Act (2004). The Civil Contingencies Act lays out the role of an “emergency coordinator” by appointment, with the direction of guidance coming from a “minister of the Crown” (CCA, Section 24).

In summary, the emergency management professional in monarchical systems supports the leadership and decision-makers during incidents and disasters. Still, the levels at which decisions are made vary based on the monarchy’s influence over the rule of law. Similar to those operating under democratic governance, the emergency manager or equivalent serves as a decision-making support for the leadership and provides recommendations for critical decisions when incidents and disasters take place. As we review a monarchical system, we will also review a single-party system with similarities and differences from an emergency management context.

Single Party Governance

Single-party governance describes those systems with either de facto or outright control over political proceedings. This governance form may encompass authoritarian regimes, communism, or forms of socialism. Still, the main characteristic tends to be systems that centralize significant power in the hands of a particular group, regime, or individual. Often, leadership structures are vertical, and there is a historical tendency to push from the top down. Without opposing parties to diversify thoughts, processes, and ideologies, a stagnant developmental trend is easily established, slowing the pace of governance improvements.

China represents a clear case of the single-party structure’s effect on the role of an emergency manager. Zhao et al. discussed methods for emergency decision-making and noted that a mandate was given by Leader Xi Jinping, “highlighting the defense focus” (Zhao et al., 2017). Flood management seems exclusively a military task in Jinping’s eyes; the language (“battle against floods”) lends to this idea. There are institutes associated with managing disasters, including one for Flood Control and Disaster Reduction and another for Water Resources and Hydropower Research. Overall, the emergency manager in China works under the influence of military-style procedures, which precede the beginnings of emergency management and its first functions in departments like Civil Defense. Many countries developed similar departments to address internal disasters, emergency management, and relief to maintain national security (e.g., Pakistan).

Despite this, there have been some recent developments in organizational structure for emergency management in China. Hu discusses how China has shifted from command-control structures towards collaborative emergency management due to the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. China’s governance system lends towards a centralized locus of power with vertical command structures, which can lead to swift decision-making but can produce inefficiencies and handicap local capacity. Policies have been established within the last decade to provide structures and guidance for local-level participation in disaster relief (Hu et al., 2020).

The emergency manager in single-party systems serves similarly to an emergency manager or equivalent in various governance forms. The militaristic approach for emergency managers was observed to be more mission-focused than community-focused. This depends on the emergency manager’s existing role or identified equivalent role by government and jurisdiction. The previously mentioned concept is also relevant for emergency management professionals, whose roles apply to all jurisdictions and governments. These roles in all forms of governance, including the single party, can apply to emergency management roles and functions within an international context.

The Developing Role of an E.M.

Framing an EM professional’s position is critical to understanding their role within the governance system. The U.S. switch from civil defense to emergency management indicates the parallel shift to a bureaucratic form of governance and a broadening of the disaster concept as a whole to include all-hazards (RAND, 2023). In this new framework, disasters are “managed” rather than defended against. Juxtapose this with Xi Jinping’s military-based framing of the responsibilities and roles associated with emergency management elsewhere.

As noted, there are several forms of government and different forms of governance, such as democratic, monarchal, and single-party. Regardless of the forms of government or governance, emergency management or disaster management-like agencies in the respective forms of governance worldwide have evolved. Through the development of this profession in every form of governance and country, there has been a variety of emergency management-like agencies that have developed to support a jurisdiction’s need to prepare, respond, recover, and mitigate disasters, incidents, planned events, and other occurrences that supersede the resources of one jurisdiction. From each of the examples discussed, there are lessons to be learned in more of the governmental organizational capacity than within an EM context. What is clear from this review is that there is a need for more research within emergency management and disaster management for all governance types and governmental levels. The available literature that considers challenges and recommendations for countries on an international scale was scattered and scarce. Research focused on identifying existing functions and options for improvement will only support countries globally and augment the development of emergency management professional capabilities at every level of their respective governments. The remaining sections expand on the need for the individual to operate within these various forms of governance and various forms of government on an international scale.

Section 2: Transferable Skills For All Emergency Management Professionals

Despite the myriad of situations that emergency management professionals may find themselves in, a review of roles across different governance systems can still provide a set of qualities that remain vital to the role of an emergency manager. Within these governance structures, this set of qualities can differentiate performance levels and guide training procedures. Shifts in organizational and procedural structures often arise out of necessity, and the same increases in disaster damages and complexity that lead to an all-hazards approach may require yet another fundamental change to how emergency managers are trained and taught. This introduces the discussion of competencies and their relation to a capable emergency management professional.

Competencies are those traits and abilities that enable individuals to align their behaviors around intended outcomes. The use of the word “competencies” when discussing a “capable” emergency management professional aligns with Sen’s approach (1999), namely that competencies are external evaluations of how internal traits are used to achieve a goal. In this same approach, capability is associated with the capacity to choose when one applies a skill to a task or goal. In this case, capable means someone can decide when to apply a skill, which is impossible if they do not have a skill (Lozano et al., 2012). As discussed in this paper, the capable EM will be deemed “competent” to the extent that the skills developed through education and training of innate ability are properly applied toward the profession’s goals. Like any competency, there is a degree of situational dependence, as some may be more critical. The same can be said of the emergency manager operating in different governance systems; there will be situations where some skill sets and competencies are relied on to a different degree. Furthermore, some competencies separate average performers from outstanding ones; these include cognitive competencies (how we process information), emotional intelligence competencies (how we process emotions), and social intelligence competencies (how we manage relationships) (Boyatzis, 2007). Competencies provide a standard for performance, define categories, and provide opportunities for feedback.

We will discuss the topic of competence to examine what has been identified by the field as a behavior associated with success in the role. The discussion will be followed by how to train the traits necessary to fulfill those behaviors (capabilities). This approach is to say that before an EM professional can be competent, they must be capable. Still, the training and education guided by established competencies will give the professional the means to be qualified. The work that has come out of FEMA’s Emergency Management Institute has helped to catalyze the development of established competencies so that improvements can be—to a certain degree—measured.

The Next Gen Core Competencies (NGCC) developed competencies to support Emergency Management education program development to ensure institutes of higher learning encouraged the development of critical traits and behaviors in their curricula. In the document, several behavioral anchors that are associated with capabilities were identified. A summary can be seen in the table below (Table 1).

| A summary of the core competencies discussed in Next Generation Emergency Management Core Competencies for Emergency Management Professionals, along with examples of where these competencies can be further developed. | ||

|

Competencies |

Behavioral Anchors The capable EM will have the following traits: |

Supplemental Opportunities for Development |

|---|---|---|

|

Operational |

Comprehensive, Progressive, Risk Driven, Integrated, Collaboration, Coordinated, Flexible, Professional, Uses EM body of knowledge |

Professional Development Seminars/Courses |

|

Critical Thinking |

Problem identification and solving, Uses of strategic thinking processes, Uses adaptive thinking processes |

Formal Education, Field Experience |

|

Ethical |

Respect, Veracity, Justice, Integrity, Service, exhibits duty to protect, Ethical treatment amongst stakeholders |

Code of Ethics |

|

Professional Development |

Reflects & Questions, understanding of confidence levels, Contribution to multidisciplinary work, Engage in Inquiry, Seeks practical applications |

Performance Reviews |

|

Domain Literacy |

Knowledge-seeking, Seeks credible sources, Applies the Scientific Method, Recognizes patterns, Recognizes interconnected Systems, Recognizes causes and implications, Understands social determinants of hazard risk, Understands political and legal processes, Promotes adaptive capacity building, Integrates technology into operations, Assesses usefulness and risk of technology, Advances technological use, Assesses implications of technology use, Guides information flow, Facilitates action between the parts and the whole system, Uses situational awareness to guide adjustments, Guides innovation processes |

Undergraduate Education, Seminars |

|

Risk Management |

Risk communication, implements risk management, optimizes risk management procedures and outcomes |

Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment, Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment, Hazard Vulnerability Analysis, or similar. |

|

Community Engagement |

Involves key stakeholders, cultivates partnerships & mutual respect, creates public value, Establishes process for expanded engagement and learning |

Public Forums |

|

Civic/Legal |

Considers policy options, has knowledge of political and legal dynamics, facilitates cross-sector connections, Builds social capital, Implements plans, Continually evaluates and improves |

Laws, Statues, and other legally established processes and policy. |

|

Leadership |

Inspires a shared vision, empowers organization members, Resolve conflict, Strategic decision-making |

Mentorship |

There may be competencies from other fields that overlap with EM and may even augment the capabilities of an EM professional. For example, adapting project management competencies has been suggested as a route to improving EM transferable skills (Boyarski, 2024) because developing emergency management programs aligns well with the phases of project management (Tager, 2022). Similar discussions have highlighted how emergency management’s shift to managing catastrophic events can inform project management practices (Willis, 2014).Similarly to the NGCC, The International Project Management Association produced a comprehensive competency baseline with 46 competence elements to establish an “adequate standard of professional behavior” for project managers (IPMA, 2006). The categories are organized with the understanding that “maximum efficiency is achieved when the person’s capability or talent is consistent with the needs of the job demands and the organizational environment” (Boyatzis, 1982). IPMA has also scaled its levels of competence to distinguish between declarative knowledge and experiential knowledge. The categories in both documents grouped competencies by individual behavior, technical expertise, and relevant contextual knowledge. Upon analysis, many of the competencies associated with project management have analogs in the EM competencies, and both disciplines could benefit from overlap (Galastri & Mitchell, 2014).

All competencies are developed to orient professionals towards a goal the profession values. So, what are the goals that need to be met? In its list of priorities for 2022 – 2026, FEMA referenced equity, community resilience to climate, and community preparedness as the top considerations. UNISDR listed amongst its goals for disaster risk reduction a substantial reduction in lost lives, infrastructure, and economic damages. Additionally, other goals aimed at improving national and local strategies, international cooperation, and access to early warning and risk assessment (UNISDR). These aims highlight the international orientation towards prioritizing resilience building within communities, a space where emergency management professionals are well equipped to operate. Considering this, there are three areas of emphasis that the modern state of affairs will require the capable emergency management professional to focus on, irrespective of governance: human-centered competencies, hazard literacy, and technological competencies.

The term human-centered competencies will include those that emphasize cognitive, intrapersonal, and interpersonal skills. Traits like divergent thinking (i.e., thinking “outside the box”; see Brooks et al., 2019), statistical numeracy (i.e., adequate knowledge of probabilities), and heuristic deliberation (i.e., considering different strategies) play a role in individual decision-making ability and problem-solving (Cokely et.al., 2018). This also includes traits encouraging interpersonal relationship building, including conflict resolution, communication strategies, and ethics. In the competencies mentioned earlier, there are several mentions of traits that incorporate these skills (e.g., adaptive thinking). While looser forms of governance can lend towards more community-based, collaborative solutions (see Schaer & Hanonou, 2017, for an example), the emergency manager, as a decision-maker, will need to employ approaches that account for the probabilistic nature of risk and associated management strategies. These human-centered competencies allow the individual to adequately understand, assess, communicate, and plan for risk, regardless of the scope of their influence.

Another set of competencies centers around hazard literacy, which covers risks to the community deriving from natural and artificial phenomena. The all-hazards approach and associated scope creep require an EM professional to become familiar with domain knowledge related to various risks. Emergency management professionals with a background in a particular hazard (e.g., fire, biological) must now familiarize themselves with several hazards, the associated risks, and exposure and effectively develop standard operating procedures to manage them. This can often be a difficult transition, as added breadth can lead to limitations in depth of knowledge and vice-versa. An alternative method to addressing this is the “top-hazards approach,” which uses risk analysis to identify the most likely regional risks and prioritizes resource allocation to the most likely scenarios (Bodas et al., 2020).

Technological competencies will also play a pivotal role in advancing the EM profession. Both new technical risks and technological solutions accompany the rapid development and integration of new technologies into everyday life. The risks and benefits are numerous and significant. Communications can be augmented through more reliable systems and devices but can be immediately limited with an intentional act. Advances in artificial intelligence have increased EM professionals’ access to data and models critical to decision-making but can pose ethical and legal concerns. Intelligent sensors can develop an interconnected network (internet-of-things) and provide real-time data about the availability and status of critical infrastructure. However, they still need to be put in the price range for many communities that could use them the most. Current applications cover weather projections, resource allocation models, risk and decision analysis, broadcast communications, and knowledge management. FEMA’s strategic foresight initiative outlines the risks and benefits in greater detail (FEMA, 2011). Despite the availability of tools to automate and improve the capacity of the EM professional, it is essential to note that there are many instances where these advancements are neither accessible nor desired by practitioners. Each innovation mentioned above is only as useful as the decision-makers decide. Technological literacy, as outlined in the NGCC, discusses the need for awareness and continual adaptation of useful technology into the operations of the emergency management professional (Feldmann-Jensen, 2017). Making the most of available resources will distinguish the forward-thinking professionals from those who struggle to adapt to job demands.

The critical areas of focus for the emergency management professional in the future will likely center around the development of traits that promote divergent thinking, an understanding of probabilistic risk, familiarity with multiple hazards and associated risk mitigation strategies, and technological literacy. These are critical traits associated with some of today’s challenges that EM professionals worldwide are most apt to.

Section 3: Educational Resources and Established Standards

The natural follow-up to what makes an emergency management professional “capable” is, “How can these capabilities be acquired?” In a field like emergency management, where the practitioner may have many diverse previous experiences, the idea of a singular source of knowledge must reflect the work or people involved. In a discussion on knowledge generation in the EM field, McEntire notes this dilemma when asking, “Should theory always be grounded in reality, and should practitioners accept new ways to advance the profession?” (McEntire, 2004). Much of the subsequent development of academic knowledge in the field has sought to align theory with practice to help develop actionable research-based strategies for improving performance.

An example of a strategy to improve performance through continuing education is the FEMA Emergency Management Professional Program, which has three levels of emergency management education: basic, advanced, and executive. This program, put on by the Emergency Management Institute (EMI), supports professional and leadership development for emergency management professionals at various levels. The EMI was established in 1951 as the Civil Defense Staff College (CDSC) and is now a part of the US Department of Homeland Security’s FEMA. The institute’s mission is to improve US officials’ competencies at all levels of government to handle the potential effects of disasters and emergencies. This mission is accomplished through developing and delivering training nationally to individuals and groups with emergency management responsibilities. The EMI provides training in several modalities, including national-level symposia, online distance learning, local course delivery, and resident (on-campus) course delivery (FEMA, 2019).

Some developed countries have taken similar approaches to disaster education, while others, like Japan, take a different route, seemingly embodying the whole community approach to emergency (disaster) preparedness. In Japan, disaster education occurs locally, starting with school-aged children and continuing through age groups. Chile, Honduras, and Mexico have adopted training from the US to develop Community Emergency Response Teams (CERT) and have encouraged grassroots resilience activities (Lyttle et.al, 2023), which can be reflected in historical accounts of a country’s processes and culture. This approach to disaster education that embodies a whole community approach can be connected to the cultural applications of the Japanese people and government.

These activities can be replaced in various countries where disaster preparedness can support low-cost resilience building for communities and jurisdictions that may need more dedicated funding for disaster preparedness on the local level. There are apparent differences in the knowledge that can be gained from existing forms of EM training, namely the academic and experiential routes. With different routes and approaches to EM training, education, and application within different governmental aspects, there are no one-shoe-fits-all approaches for disaster preparedness training for communities or preparation for professionals and practitioners. More discussion on the differences can be found in Bereiter and Scardamalia, 2006.

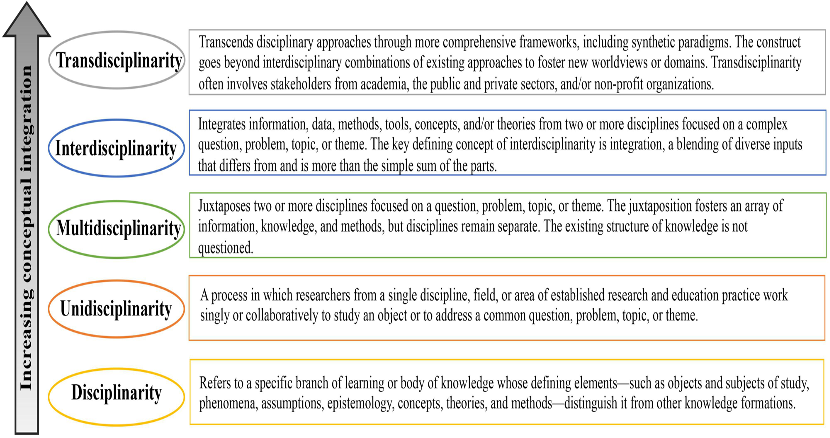

While much of the discussion focuses on emergency management education, there is value in discussing other professions with roles and responsibilities in disaster response. The idea that these other professions (e.g., public health, public administration, engineering, law, natural resources, and environmental management, non-profit administration, social work, business administration, and hospital administration) have essential roles in disaster response was identified and reiterated by Jensen, et al. (2012, 2014), and recently cited as the distributed functions of emergency by McEntire (2023). Borrowing from Peek, et al. (2020), we can infer that today’s complex nature of emergencies and disasters follow convergence theory, and thus need solutions that transcend a single discipline. Figure 1 depicts the increasing conceptual integration from unidisciplinary thought to transdisciplinary thought. This conceptual integration could be achieved through interdisciplinary learning or interprofessional education (IPE). IPE occurs when students from two or more fields study and learn together with the shared goal of collaborative practice.

Note: From “A Framework for Convergence Research In The Hazards and Disaster Field: The Natural Hazards Engineering Research Infrastructure CONVERGE Facility,” by L. Peek, J. Tobin, R.M. Adams, H. Wu, and M.C. Mathews, 2020, Frontiers in Built Environment, 6 (doi: 10.3389/fbuil.2020.00110). CC BY 4.0

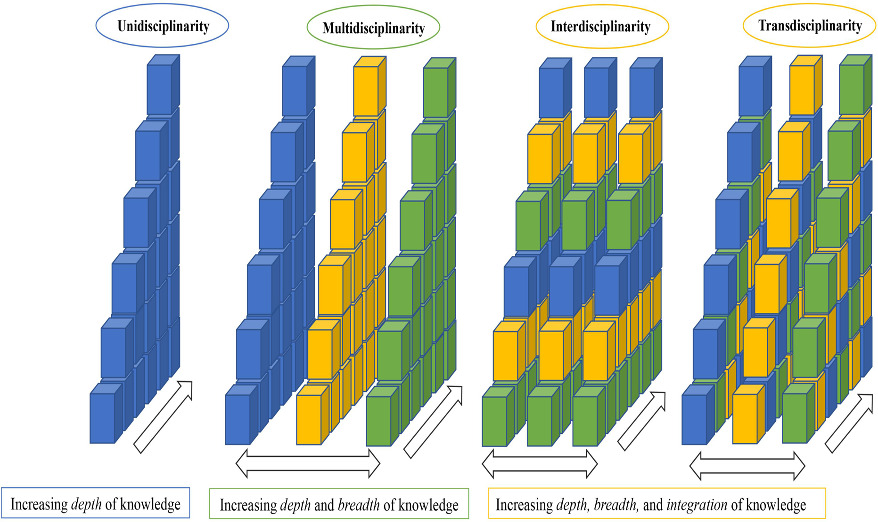

What could be gained from a shift to interprofessional education? Competencies gained from interprofessional education in undergraduate education or equivalent include values and ethics, roles and responsibilities, teamwork, communication, and interprofessional conflict resolution (IPEC, 2023; CIHC, 2010). Table 2 presents the IPE collaborative practice competency domains and their meaning. These competencies, along with the acquisition of other soft skills, are an exemplification of knowledge building. Figure 2 depicts the convergence requirements for integrating knowledge, in-depth and breadth, from a single discipline (interdisciplinarity) to transdisciplinary.

|

Interprofessional Collaborative Practice Competency Domains |

|

|---|---|

|

Values and Ethics |

Working with team members to maintain a climate of shared values, ethical conduct, and mutual respect. |

|

Roles and Responsibilities |

Using the knowledge of one’s role and team members’ expertise to address (health) outcomes. |

|

Communication |

Communicating in a responsive, responsible, respectful, and compassionate manner with team members. |

|

Teams and Teamwork |

Applying values and principles of team science to adjust to one’s role in various settings. |

|

Interprofessional Conflict Resolution |

Actively engaging with others in dealing effectively with interprofessional conflict. |

Other methods can be used to elevate the “human-centered competencies” that were discussed in section 2. Exposure to common misjudgments and discussing corrective measures and adjustments can help refine people’s natural heuristics. The adjustments would need to take an applicable approach to the needs of a community, justification, and government to include but not be limited to processes and policies. The educational aspects of supporting a capable emergency manager and emergency management professional are taken into account primary and secondary disciplines that support the interconnectedness and intersectionality of the EM profession.

Discussion and Recommendations

Emergency management has a history of adapting to new challenges. Just as the threat of nuclear war catalyzed and the events of 9-11 prompted the development of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, the emerging risks associated with disasters and technology will likely shape the future operations and scope of emergency management professionals worldwide. As much as those were changes in organization structure, the practitioner will be affected by this. Based on observations from this chapter and the experience of the writers, recommendations to support the development of a capable emergency manager are highlighted in this section.

Recommendation 1: Continue the development of the body of knowledge

Knowledge development will continue to contribute to the advancement of emergency management, as it is at the core of what is needed to be “capable.” Among the markers associated with a profession is the continual development of an emergency management body of knowledge (EMBOK). Research can focus on questions like: “Should more be required of emergency management professionals to address today’s risks?” or “What perspectives should be integrated from other fields to supplement the existing body of knowledge?” Knowledge of the neighboring disciplines will help the professional respond effectively to interdisciplinary problems. Another product of integrating knowledge from other disciplines is a convergence toward uniformity of terminology and definitions.

Recommendation 2: Encourage cultural competencies and broaden recruitment to improve resilience and equity

Cultural competencies are important for adequately establishing relationships and communication strategies amongst the communities that the EM professionals serve. As the field of emergency management seek to progress, culturally competency for professionals may require more considerations of what constitutes an equitable system within their service areas to ensure those with more severe needs are cared for. Ideally, integrating considerations of culture into decision-making and planning will result in resilient and sustainable practices that equitably support the whole community within a given jurisdiction and government. What remains essential to any efforts to support the whole community is to adequately advocate for considering equity in all operations and all phases of emergency management. Producing agreed-upon measurables that bridge across different perspectives and disciplines is a continual and necessary task of professionals globally.

The discussions around equity are also relevant when considering the profession’s diversity. Capabilities can arise and be developed from unique life experiences, highlighting some of the benefits of seeking capable professionals amongst all people within a given community. As emergency management professionals are tasked with supporting the well-being of all individuals and populations within their communities, this would naturally seem to involve continuing efforts to engage with and recruit from these communities. Each nation has its population dynamics to consider. Indices used for vulnerability in the US where race and ethnicity are acknowledged. However, inequity in other nations may not be as strongly correlated or more correlated to these factors as in ethnically heterogeneous nations such as the US. The “Whole Community Approach” that FEMA has taken may look different for other nations, which may give more weight to other categories, processes, and policies to reach this approach within a practical sense. Each emergency management professional, as part of the aforementioned “human-centered competencies”, must know the unique historical, social, economic, cultural, and environmental factors contributing to a lack of resilience for those within their jurisdiction. These competencies will help to inform decision-making that raises the resilience of the whole community and addresses the needs of those at the margins.

Recommendation 3: Establish a system to evaluate system procedures

There is a need to evaluate established systems and procedures that support efficiency from fiscal and workforce perspectives. A theory such as the Innovative Structural Theory of Emergency Management (IST-EM) is a theoretical framework that supports organizational evaluation within an emergency management context. This is a novel approach to innovative applications to modify an organization to review, analyze, and, if recommended, reform the existing organizational structure’s composition, process, or practice (Richardson, 2023). The theory can be used for organizations in various disciplines, but for the sake of this research, its application is directed and created practically for use within Emergency Management organizations. This theory refers to an organizational framework and process to support and manage innovation within Emergency Management, its operational structure as a subsection of public administration, and its functions for the community served within a jurisdiction.

Recommendation 4: Improve data collection on EM practices worldwide

Due to the standard practice of organizational structures, demographic data, and associated policies that influence the profession and interconnected sub-disciplines within the emergency management context, there have been improvements in the profession. More research on the organizational structures associated with international emergency management would help improve the opportunity to share lessons learned and evidence-based best practices. This can help practitioners worldwide access information to help with decision-making and identify more significant trends that the profession can use to move forward.

Limitations

Throughout this chapter’s development, several limitations were identified as noteworthy. One of these limitations is related to the relative dearth in accessibility of organizational emergency management literature, as it tends to be unequally distributed towards coverage of the response phase and will typically be concentrated in Western nations. The authors also deliberated on the most effective way to categorize the globe for comparisons of emergency management professionals within an international context. However, they recognized that there may have been other methods to do so that would yield more insight. An additional limitation is that the fundamental lens of an American (United States) paradigm can expose this analysis to a path-dependent bias based on the makeup of the research team and exposure to American emergency management agencies (FEMA) and American processes to emergency management professional development (Trouve, 2010). These are impactful limitations that can be overcome with the recommendation of future research within this area from different continental and governance-based paradigms to diversify and allow comparison of the needs and provide a more inclusive recommendation to emergency management professionals.

Conclusion

The crucial part of establishing a profession is identifying qualified candidates. A standard of expertise and educational attainment separates a professional from those with more general knowledge. As emergency management develops as a profession, several opportunities exist to establish a firm foundation for the future. Development can be accelerated if efforts are focused on surveying existing practices around the globe and adapting knowledge from other fields. Insights from public health, engineering, public administration, and social sciences have already shaped the EMBOK. However, it is only possible to assess the needs related to foundational knowledge and traits discussed here with consistent and well-researched global perspectives. The authors hope this chapter contributes to a discussion and highlights the need for continued development of both the emergency management professional and the profession from the direction of comparing the international landscape of emergency management (this chapter examined it through the lens of governance types) to educational baselines for professionals and practitioners. Even in an American context, there are established systems for emergency management, but those functions are only sometimes applicable. The writers believe it is meant to be used in only some cases. When applicable, the uses for everyday operations would fundamentally differ from disaster or activation operations to support a jurisdiction or government. A system should be developed to span everyday operations and activation. Two separate structures and applications would need to be identified. Then, a transitional phase would be recommended to support a functioning and flexible bimodal system for emergency management organizational use.

Throughout this chapter, many insights discuss aspects of the capable emergency management professional from an international context. Discussions in the first section centered on the role that the development of emergency management organizations and agencies plays in defining the scope of the emergency manager professional. Across governance types, some similar limitations and operations have developed from a militaristic or civil defense paradigm. This development and divergence of governance types has required EM professionals to emphasize different skill sets to meet the community’s needs. Even so, some identifiable traits and skills promote success across the board, several of which have been highlighted here. The methods of developing emergency management skill sets, bodies of knowledge, and transferable skills vary from organization to organization, just as the educational resources and established standards, terms, and concepts also differ. Focusing on the traits that stand out as critical for the subsequent phases of emergency management as a profession will help develop future professionals to meet the challenges of tomorrow.

References

Billett, S., Harteis, C., & Gruber, H. (2014). International Handbook of Research in Professional and Practice-based Learning. In Springer international handbooks of education. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8902-8

Bodas, M., Kirsch, T. D., & Peleg, K. (2020). Top hazards approach – Rethinking the appropriateness of the All-Hazards approach in disaster risk management. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 47, 101559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101559

Boyatzis, R. E. (2008). Competencies in the 21st century. Journal of Management Development, 27(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621710810840730

Brooks, B., Curnin, S., Owen, C., & Boldeman, J. (2019). New human capabilities in emergency and crisis management: from non-technical skills to creativity. The Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 34(4), 23–30. http://ecite.utas.edu.au/135484/2/135484%20-%20New%20human%20capabilities%20in%20emergency%20and%20crisis%20management.pdf

Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative. (2010). A national interprofessional competency framework. CIHC. https://phabc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/CIHC-National-Interprofessional-Competency-Framework.pdf

Civil Contingencies Act 2004. (2004). https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2004/36/contents

Cokely, E. T., Feltz, A., Ghazal, S., Allan, J. N., Petrova, D., & García‐Retamero, R. (2018). Skilled decision theory: from intelligence to numeracy and expertise. In Cambridge University Press eBooks (pp. 476–505). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316480748.026

Downey, D. C., & Myers, W. M. (2020). Federalism, intergovernmental relationships, and Emergency Response: A comparison of Australia and the United States. The American Review of Public Administration, 50(6–7), 526–535. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074020941696

Feldmann-Jensen, S., Jensen, S. J., Smith, S. M., & Vigneaux, G. (2017). The next generation core competencies for emergency management: Handbook of behavioral anchors and key actions for measurement. FEMA. https://training.fema.gov/hiedu/docs/emcompetencies/final_%20ngcc_and_measures_aug2017.pdf

FEMA SFI. (2011, May). Technological Development and dependency: long-term trends and drivers and their implications for emergency management. https://www.fema.gov/pdf/about/programs/oppa/technology_dev_%20paper.pdf

Florida Legislature. (2024, January 29). The 2023 Florida Statutes – Chapter 252. Statutes & Constitution : view statutes : Online Sunshine. http://www.leg.state.fl.us/statutes/index.cfm?App_mode=Display_Statute&URL=0200-0299%2F0252%2F0252PARTIContentsIndex.html

Galastri, C., Mitchell, B., & Willis, H. (2014). Project management and emergency management: dealing with changes in a changing environment. Project Management World Journal, 3(9). https://pmworldjournal.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/pmwj26-sep2014-Galastri-Mitchell-project-management-and-emergency-management-SecondEdition2.pdf

Hubbard, B. (2021). Responder to emergency manager: How do the skills translate? – Homeland Security Affairs. Homeland Security Affairs Journal: Pracademic Affairs, 1, 5. https://www.hsaj.org/articles/17207

ICS-300 Intermediate ICS for Expanding Incidents. (2013). FEMA.

Interprofessional Education Collaborative. (2023). Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Preliminary draft revisions. IPEC. https://www.ipecollaborative.org/assets/core-competencies/IPEC_Core_Competencies_2023_Prelim_Draft_Revisions%20(2023-04-12).pdf

IPMA. (2006). ICB IMPA Competence Baseline Version 3.0.

Lozano, J. F., Aristizábal, A. B., Peris, J., & Hueso, A. (2012). Competencies in Higher Education: A Critical Analysis from the Capabilities Approach. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 46(1), 132–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9752.2011.00839.x

Lyttle M, Poblete P, Encinas L. Community Emergency Response Teams and Disaster Volunteerism in Latin America. J Bus Contin Emer Plan. 2023 Jan 1;16(4):366-378. PMID: 37170455.

Overly, K. R. (2023, June 16). The evolving status of emergency management organizations. Domestic Preparedness. https://www.domesticpreparedness.com/articles/the-evolving-status-of-emergency-management-organizations

Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L. A., … McKenzie, J. E. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 372, n160. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n160

Peek L., Tobin J., Adams R.M., Wu H., & Mathews M.C. (2020). A framework for convergence research in the hazards and disaster field: the natural hazards engineering research infrastructure converge facility. Frontiers in Built Environment, 6. doi : 10.3389/fbuil.2020.00110

Schaer, C., & Hahonou, É. K. (2017). The real governance of disaster risk management in peri-urban Senegal. Progress in Development Studies, 17(1), 38–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464993416674301

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA43059927

Tager, A. (2023, November 22). Project management approach in emergency management. Domestic Preparedness.

The Emergency Management Institute at 70: From Civil Defense to Emergency Management in an Education and Training Institution. (2023). RAND Corporation. https://doi.org/10.7249/RRA1523-2

The 2023 Florida Statutes. Statutes & Constitution : view statutes : Online Sunshine. (2024, February 17).

Treib, O., Bähr, H., & Falkner, G. (2007). Modes of governance: towards a conceptual clarification. Journal of European Public Policy, 14(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/135017606061071406

UNISDR Strategic Framework (2016-2021). (2015). Retrieved February 18, 2024, from https://www.unisdr.org/files/51557_unisdrstrategicframework20162021pri.pdf

O’Brien, G., & Read, P. (2005). Future UK emergency management: New wine, old skin? Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal, 14(3), 353–361. https://doi.org/10.1108/09653560510605018

Richardson, Kesley, “Quality Check: How Good is Your Emergency Management Program?” (2023). West Chester University Doctoral Projects. 229. https://digitalcommons.wcupa.edu/all_doctoral/229

Trouvé, H., Couturier, Y., Etheridge, F., Saint-Jean, O., & Somme, D. (2010). The path dependency theory: Analytical framework to study institutional integration. The case of France. International Journal of Integrated Care, 10, e049.

University of the District of Columbia. (n.d.). Learning Resources Division: Government Information Help Guide: Government Agencies. Government Agencies – Government Information Help Guide – Learning Resources Division at the University of the District of Columbia. https://udc.libguides.com/c.php?g=670839&p=7813725#:~:text=A%20government%20agency%20is%20a,field%2C%20or%20area%20of%20study.

Yeskey, K. S. (1994). Domestic disaster response: FEMA and other governmental organizations. Military Preventive Medicine, 2, 1363-1374.