20 Aligning International Strategy to Standards in Emergency Management: Current and Emerging Issues

Marcelo M. Ferreira, PhD, CEM®

Author

Marcelo M. Ferreira, PhD, CEM®, PMP, Arkansas State University

Keywords

emergency management, disaster management, disaster risk reduction, strategy, frameworks, standards

Abstract

This chapter explores the alignment of international strategy in disaster risk reduction and standards for emergency (and disaster) management programs. International frameworks have provided a foundation to relay strategy and provide guidance to handle the impacts of hazard events across nations while highlighting the importance of proactively working toward reducing risk, enhancing preparedness, and strengthening resilience. Standards have emerged to provide benchmarks for applications of emergency and disaster management programs and influence policies, laws, regulations, and guidance. However, adherence to standards is limited, and clarity over the alignment of core concepts, strategies, frameworks, and standards in the field remains elusive. Without clear and consistent boundaries for the body of knowledge, the potential grows for external influences to shape practices rather than research and best practices. This study aims to present the evolution of international disaster risk reduction strategy and the emergence of emergency management program standards and explore related key terms, core concepts, and priority areas.

Introduction

International strategy has endeavored to coalesce global efforts towards reducing risk, enhancing preparedness, and promoting effective response and recovery from disaster. Frameworks established by the United Nations were developed to share strategies and provide guidance to nations in their holistic disaster risk reduction and emergency (and disaster management) efforts. Alongside international strategy, standards have arisen as benchmarks for emergency management programs across levels of governance (e.g., federal, state, local) and sectors (e.g., public, private, nonprofit, infrastructure). However, alignment between international strategy and standards in emergency management remains challenging, as there is limited adherence to benchmarks, confusion regarding core concepts, and few studies on the topics. Furthermore, a lack of clarity and consistency in core concepts in the field can make it difficult to compare and learn from different approaches (Wisner & Alcántara-Ayala, 2023). This study aims to explore key terms, core concepts, and priority areas related to alignment of international strategy in disaster risk reduction and standards in emergency management.

An international focus has raised awareness of the importance of proactively addressing disaster risk. However, variations in core concepts have led to challenges in achieving consistency in practice and research across the globe. It is important to address challenges and strive for consistency to improve the effectiveness of emergency management and disaster risk reduction efforts globally (Burkle et al., 2001; Delshad et al., 2020). As disasters do not recognize borders and have the potential to cause widespread impacts, international cooperation and collaboration are necessary for effective research and practice related deliverables. The interdisciplinary nature of the topic further applies across sectors (e.g., public, private, and nongovernmental), levels (e.g., local, state, federal), and disciplines (e.g., public administration, engineering, social sciences, public health, urban planning).

Emergency management programs have emerged within organizations and agencies to organize and coordinate related efforts toward addressing the impacts of emergencies and disasters. Comparatively, “international disaster management” applies to coordination efforts to support the response when a nation’s capacity has been exceeded, which relates to humanitarian relief (Bullock, Haddow, & Coppola, 2020). While it is widely acknowledged that “all emergencies start and end locally,” global coordination has striven to address growing global impacts beyond the capacity of any one nation to address. However, conceptual confusion and lack of clarity in defined key concepts in emergency (and disaster) management and disaster risk reduction hinder effective international cooperation and implementation of strategies and standards.

The body of knowledge widely recognizes the diversity of definitions among key concepts in the field. For example, the terms “emergency management” and “disaster management” are often used interchangeably (United Nations, 2016). McEntire (2018) highlights challenges in coalescing around one definition of “emergency management,” describing how a common definition has yet to be established for research and practice. Thus, it is necessary to further explore and analyze the common foundations for fostering the exchange of knowledge and benchmarking success.

Standards in Disaster Risk Reduction

Strategy established at the international level has led to a global focus on the importance of proactively addressing the impacts of disasters. Frameworks have raised awareness of strategies and provided guidance for nations based on best practices and, unfortunately, common lessons learned. During this time, standards have emerged to benchmark programs and efforts across the international disaster risk reduction strategic umbrella, including emergency management. Standards are “defined loosely as a set of tools that embodies national and/or international best practices in any given field…standards are by definition not mandatory” (Jachia, 2014, pg.2). The implementation of standards may be voluntarily adopted by organizations and jurisdictions, and may also be incorporated into policy, laws, regulations, national frameworks, and grant requirements. Standards related to disaster risk reduction encompass a wide range of interrelated areas, including emergency management, resilience, sustainable development, and climate change (Jachia, 2014).

An analysis of voluntary standards related to disaster risk reduction is provided in a background paper, “Standards and Normative Mechanisms for Disaster Risk Reduction,” for the 2015 Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction (Jachia, 2014). Standards are categorized as 1) risk prevention, 2) risk reduction, and 3) strengthening crisis management capacity (see Table 1). Emergency management-related standards, which “enable businesses and communities to be better prepared to crisis, to absorb shocks and to rebuild better,” are included within the category “strengthening crisis management capacity” (Jachia, 2014, pg. 4). While there are many standards related to international disaster risk reduction across these categories, this study specifically focuses on the alignment of standards related to emergency management programs.

| Type of Standard in DRR | Explanation | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Risk Prevention | “Policy and business strategies are geared towards sustainable and resilient development.” |

|

| Risk Reduction | “Systemic risk management is implanted and specific risks are addressed…Product and process standards assist in minimizing risks of disasters to the built environment and to key infrastructure.” |

|

| Strengthening Crisis Management Capacity |

“Best practice and standards in business continuity & emergency management enable business & communities to be better prepared to crisis, to absorb shocks and to rebuild better.” |

|

Standards provide a benchmark for applications of emergency management programs across public and private sectors and influence policies, laws, regulations, and guides. Standards related to emergency management programs continue to evolve, initially emerging from a focus on incident response to a more holistic focus on organizing and managing across the disaster cycle (e.g., mitigation, prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery) (Coppola, 2021; Jachia, 2014). These standards and frameworks attempt to increase consistency and coherence in implementing strategies, enabling countries and organizations to effectively coordinate efforts in emergency management. However, adherence to standards is not widely observed, and clarity over standards used in the field remains elusive (Bowen, 2008; Jensen & Ferreira, 2023). Furthermore, implementing these strategies and frameworks across sectors and nations is not always consistent, leading to variations in applying concepts in practice. Without clear and consistent boundaries for the body of knowledge, the influence of acute crisis and politics to shape practices grows (McEntire, 2007).

This chapter explores the current and emerging issues in aligning international disaster risk reduction strategy with internationally recognized emergency (and disaster) management standards. An introduction presents concepts related to strategy and standards in emergency management and disaster risk reduction. A literature review follows, which provides a narrative of the evolution of international approaches to disaster, applications of international strategies, current internationally recognized emergency management program standards, and research on standards in the topic. The chapter then presents the methodology for analyzing the research question: How do internationally recognized standards for emergency management programs align with international strategy in disaster risk reduction? The findings and solutions follow, which lead to a discussion of the analysis of findings and recommendations.

Literature Review

Modern approaches to international disaster risk reduction and emergency management have been influenced by research and practice from disparate efforts of nations and disciplines, each attempting to implement the latest best practices and lessons learned from their unique perspective and context (McEntire, 2008). Global strategies and models have aimed to serve as a basis for establishing strategies in countries worldwide, emphasizing the need to proactively reduce risk and improve preparedness for increasing hazards. However, the consistent implementation of these strategies and frameworks across nations varies, resulting in differences regarding how concepts and practices are applied. These variations stem from factors such as differing political will, resource availability, institutional capacities, and cultural contexts. Nevertheless, these variations in fundamental principles hinder achieving uniformity and effectiveness in regional disaster management practice and research (Bullock, Haddow, & Coppola, 2020; Coppola, 2021). A better understanding of how international frameworks and standards are aligned is needed to tackle these challenges and promote a more unified approach toward reducing disaster risk.

Evolution of the International Approach to Disasters

The evolution of strategy in international disaster risk reduction and disaster management has been influenced by the transition from a reactive response to the recognition of a need for a comprehensive and integrated proactive approach (Coppola, 2021; McEntire, 2008; Wisner and Alcántara-Ayala, 2023). Strategically and in line with this shift, the international community has developed frameworks and initiatives that aim to address various aspects of disaster risk reduction and management across nations, with the understanding of the greater need to support developing nations in building capacity for disaster resilience (Coppola, 2021; UNDRR, 2022) However, despite the efforts to develop a global strategy and corresponding frameworks, the field’s evolution has led to challenges in aligning concepts.

Evolving from the Civil Defense era in the 1950s, emergency management had initially focused on responding to attacks within nations (Coppola, 2021) but expanded to encompass an all-hazards approach and “comprehensive emergency management” by the 1980’s. In the international community, as a reaction to the increasing impacts of hazard events and the recognized need for coordinated international efforts, an initial initiative was developed in the 1980s by the United Nations, leading to a series of agreements designed to promote international cooperation in disaster risk reduction. The driving force for international cooperation and strategy has been the recognition of the increasing hazard events and the ability of humans to proactively prevent impacts from occurring and to effectively manage them when they do occur (Coppola, 2021; Delshad et al., 2020; United Nations, 1987).

In 1987, the UN General Assembly Resolution 42/169 designated the 1990s as the “International Decade for Natural Disaster Risk Reduction,” resulting in a series of international conferences and agreements to develop strategies and frameworks for disaster risk reduction and encourage global cooperation (see Table 2). The objective was to engage in focused international action to establish strategies to reduce the loss of life, property damage, and social and economic disruption caused by natural disasters; a focus on preparedness, prevention, and mitigation was emphasized (United Nations, 1987). The Yokohama Strategy, adopted in 1994 (United Nations, 1994), resulted from this 1987 initiative.

| Document | Year(s) | Key Focus | Notable Achievements |

|---|---|---|---|

| UN General Assembly Resolution 42/169

|

1987 | Encouraging international cooperation for disaster risk reduction. | Designated the 1990s as the “International Decade for Natural Disaster Reduction.” |

| Yokohama Strategy and Plan of Action

|

1994 | Guidelines for natural disaster prevention, preparedness, and mitigation. | First agreement to provide a detailed strategy for disaster risk reduction. |

| Hyogo Framework for Action

|

2005-2015 | Building resilience of nations and communities to disasters. | First agreement to detail the work required from all sectors to reduce disaster losses. |

| Sendai Framework | 2015-2030 | Reducing disaster risk and losses. | Most recent agreement which provides concrete actions for disaster risk reduction. |

The Yokohama Strategy and Plan of Action for a Safer World coalesced international efforts toward a common set of principles, suggested a basis for a strategy, and provided recommended actions for nations to take to reduce risk as the first comprehensive guidelines for disaster risk reduction and established the foundation for a cooperative approach. The Yokohama Strategy and Plan of Action for a Safer World also emphasized the importance of local action and community participation. It recognized the crucial role of risk assessment, disaster prevention, and preparedness in reducing the need for disaster relief. The strategy highlighted the need for integrating disaster risk reduction into development planning and emphasized the importance of knowledge sharing, education, and awareness-raising (Coppola, 2021; Delshad et al., 2020; United Nations, 1994).

Building upon the foundations of the Yokohama Strategy, the Hyogo Framework for Action (2005-2015) focused on building the resilience of nations and communities to disasters (United Nations, 2005). Signed and adopted by 164 nations, the Hyogo Framework for Action emphasized the development of national action plans by all countries (Coppola, 2021). The Hyogo Framework for Action aimed to 1) strengthen disaster risk reduction as a priority at the national and local levels, 2) improve early warning systems, 3) utilize knowledge and innovation for safety and resilience, 4) reduce underlying risk factors, and 5) strengthen preparedness against disasters (United Nations, 2005). However, despite these efforts, the social, cultural, and economic damages caused by disasters continued to grow. To formulate a strategy for the next 15 years, and in recognition of a changing risk profile globally, the international community came together again in 2015 in Sendai, Japan, to adopt the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015 – 2030 (United Nations, 2015).

The Sendai Framework broadened the scope of disaster risk reduction, focusing on both natural and man-made hazards and related environmental, technological, and biological hazards and risks (Coppola, 2021; United Nations, 2015). There was also an emphasis on the need for an improved 1) understanding of disaster risk, 2) strengthening of disaster risk governance, 3) investing in disaster risk reduction, and 4) preparedness to “Build Back Better” in recovery (United Nations, 2015). Today, the Sendai Framework guides the international community’s efforts in disaster risk reduction, marking a significant evolution in global disaster management standards since initial iterations of international strategies to address global disaster risk. The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction is the most recent and comprehensive international framework for disaster risk reduction (Coppola, 2021; Delshad et al., 2020).

The Sendai Framework strongly emphasizes the need to understand and manage disaster risk. Seven global targets and four priorities for action are included in the framework (see Textbox 1). In addition, the Sendai Framework recognizes the importance of stakeholders and their roles in disaster risk reduction through an integrated and inclusive approach across “economic, structural, legal, social, health, cultural, educational, environmental, technological, political and institutional measures that prevent and reduce hazard exposure and vulnerability to disaster, increase preparedness for response and recovery, and thus strengthen resilience” (United Nations, 2015, pg. 12). The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, adopted in 2015, is the most recent and comprehensive international framework for disaster risk reduction (Delshad et al., 2020). However, despite the progress in international frameworks, implementation and adherence are still not widely observed (Wisner and Alcántara-Ayala, 2023).

Textbox 1. Sendai Framework Priorities

Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction Priorities and Global Targets

Priorities

Priority 1: Understanding disaster risk.

Priority 2: Strengthening disaster risk governance to manage disaster risk.

Priority 3: Investing in disaster risk reduction for resilience.

Priority 4: Enhancing disaster preparedness for effective response and to “Build Back Better” in recovery, rehabilitation and reconstruction.

(United Nations, 2015, pg. 13)

Global Targets

Target A: “Substantially reduce global disaster mortality by 2030, aiming to lower the average per 100,000 global mortality rate in the decade 2020–2030 compared to the period 2005-2015;”

Target B: “Substantially reduce the number of affected people globally by 2030, aiming to lower the average global figure per 100,000 in the decade 2020–2030 compared to the period 2005–2015;”

Target C: “Reduce direct disaster economic loss in relation to global gross domestic product (GDP) by 2030;”

Target D: “Substantially reduce disaster damage to critical infrastructure and disruption of basic services, among them health and educational facilities, including through developing their resilience by 2030;”

Target E: “Substantially increase the number of countries with national and local disaster risk reduction strategies by 2020;”

Target F: “Substantially enhance international cooperation to developing countries through adequate and sustainable support to complement their national actions for implementation of the present Framework by 2030;”

Target G: “Substantially increase the availability of and access to multi-hazard early warning systems and disaster risk information and assessments to people by 2030.”

(United Nations, 2015, pg. 11)

Applying International Strategies

Strategies and frameworks established at the international level are applied across sectors in nations and communities to enhance disaster risk reduction efforts and to better manage the impacts of hazard events. National governments play a crucial role in translating and implementing international strategies and priorities for disaster risk reduction (Coppola, 2021; Delshad et al., 2020) and have the primary responsibility to prevent and reduce disaster risk within their territories (Wahlström, 2015). Furthermore, national governments are responsible for strengthening disaster risk governance, ensuring effective coordination and collaboration among relevant stakeholders, and allocating resources for investment in disaster reduction initiatives. Through national-level implementation, countries aim to enhance their understanding of disaster risk by conducting assessments and promoting research on hazards, vulnerabilities, and exposure (Delshad et al., 2020; Johansson & Nilsson, 2006).

Frameworks, standards, policies, regulations, statutes, and laws are developed and implemented at the national level, while the Sendai Framework encourages nations to align with international strategies and priorities (Johansson and Nilsson, 2006; United Nations, 2015). To address the unique challenges and risks they face, many nations have implemented national-level strategies and frameworks of their own. These strategies are often tailored to the specific context and needs of each country, considering factors such as geographical location, climate, socioeconomic factors, culture, and resources, and must be cognizant of the culture to which it is being applied (Delshad et al., 2020; Johansson & Nilsson, 2006).

Ideally, national policies are further applied at the state, regional, and local levels, where policies and standards are adapted to their specific needs, creating localized strategies. Over time, standards, serving as benchmarks for emergency management programs, have become more comprehensive and inclusive, recognizing the importance of involving all sectors of society and encouraging proactive disaster risk reduction efforts over a response-focused mindset (Coppola, 2021). However, barriers remain in applying a cohesive strategy in nations across the globe.

Challenges in implementing international strategies for disaster risk reduction at the national level include limited resources, institutional capacity gaps, conflicting priorities and interests, and socio-political factors (Coppola, 2021; United Nations, 2015). Furthermore, disaster risk reduction strategies must be adapted to local contexts and consider the unique challenges faced by different communities and regions. Moreover, sustainable funding and adequate resource allocation are crucial to effectively implement international strategies at the national level. In order to successfully implement international strategies for disaster risk reduction at the national and local levels, governments must overcome challenges such as limited resources and institutional capacity gaps while navigating a compendium of terms, concepts, priorities, and approaches. The journey from international strategy to local implementation illustrates the dynamic and multi-layered nature of disaster risk reduction and management standards, which can exacerbate challenges in attempting to align efforts.

Interdisciplinary Emergency Management Program Standards

Standards provide a benchmark upon which to base practices and guide programs across sectors. Some standard-setting groups are leveraged within nations for standards related to emergency management programs, which may be applied across disciplines and sectors. These standards aim to help ensure consistency, coherence, and effectiveness, allowing for better coordination and collaboration among different stakeholders involved in emergency management (Wahlström, 2015). In emergency management, two internationally recognized standard-setting bodies maintain emergency management program standards, including the Emergency Management Accreditation Program (EMAP) and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). These standard setting bodies and their emergency management program standards provide a technical and operational perspective, complimenting strategic, high-level guidance.

Program-level standards are crucial in implementing disaster risk reduction and emergency management strategies across various disciplines and sectors. These standards attempt to provide a common language and establish guidelines for implementation within each unique programmatic context (Stratton, 2017). However, alignment is inconsistent, and widespread use or adherence to standards has not been observed. A consensus on the specific standards to be implemented at the program level and on their application and enforcement would advance research and practice in the field.

EMAP Emergency Management Standard

The Emergency Management Accreditation Program (EMAP) maintains the Emergency Management Standard (EMAP Standard) and accredits emergency management programs based on adherence to the standard (Emergency Management Accreditation Program, 2019). EMAP, an independent nonprofit, establishes standards for programs in emergency management and accredits them, regardless of their size or organizational structure (Jensen & Ferreira, 2023). The EMAP Standard is a globally recognized benchmark for emergency management programs (Shiley, 2018). It applies across all phases of emergency management, including mitigation, prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery and emergency management programs of all varieties. The standards cover a range of areas such as hazard identification, planning, resource management, training and exercises, communications, and public information (EMAP, 2019) (see Table 3). In the United States, the EMAP Standard has been adopted by the American National Standards Institution (ANSI), which is the U.S. representative to ISO, and has been endorsed by the United States Council of the International Association of Emergency Managers (IAEM) (Shiley, 2018).

Although the EMAP Standard may apply globally, adoption and accreditation is currently centered in the United States. As of 2024, there were 91 emergency management programs accredited by EMAP. 95.6% (n=87) of EMAP programs (i.e., State Programs, Local Programs, Institutions of Higher Education Programs, and Private Sector Programs) were based in the United States. However, it is not possible to determine the number of programs worldwide using the EMAP Standard as a benchmark.

| Chapter | Sub-Section |

|---|---|

| 1. Administration | 1.1: Purpose 1.2: Application |

| 2. Definitions | 2.1: Applicant 2.2: Continuity of Government 2.3: Continuity of Operations 2.4: Disaster 2.5: Emergency 2.6: Emergency Management Program 2.7: Essential Program Function(s) 2.8: Gap Analysis 2.9: Hazard 2.10: Human-caused 2.11: Incident 2.12: Incident Management System 2.13: Intelligence 2.14: Jurisdiction 2.15: Mitigation 2.16: Mutual Aid Agreement 2.17: Preparedness 2.18: Prevention 2.19: Procedure(s) 2.20: Recovery 2.21: Resource Management Objective(s) 2.22: Response 2.23: Stakeholder(s) 2.24: Standard 2.25: Technical Assistance |

| Chapter 3: Emergency Management Program | 3.1: Program Administration and Evaluation 3.2: Coordination 3.3: Advisory Committee 3.4: Administration and Finance 3.5: Laws and Authorities |

| Chapter 4: Emergency Management Program Elements | 4.1: Hazard Identification, Risk Assessment and Consequence Analysis 4.2: Hazard Mitigation 4.3: Prevention 4.4: Operational Planning and Procedures 4.5: Incident Management 4.6: Resource Management, Mutual Aid, and Logistics 4.7: Communication and Warning 4.8: Facilities 4.9: Training 4.10: Exercises, Evaluations and Corrective Actions 4.11: Emergency Public Information and Education |

International Organization for Standardization (ISO)

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) is an international nongovernmental organization that develops and publishes standards in various fields, including emergency management. However, ISO does not perform certification or accreditation of programs itself (Johansson and Nilsson, 2006). ISO membership includes standard setting bodies from over 160 countries, who provide technical and operational standards that organizations and governments can adopt. ISO Technical Committee (ISO/TC) 292: Security and Resilience is responsible for the development of international standards related to emergency management, including ISO 22320 for emergency management, ISO 22316 for organizational resilience, ISO 22398 for exercises and testing, and ISO 22300 for vocabulary (ISO/TC 292, 2024; Johansson and Nilsson, 2006). However, other technical committees within ISO, such as ISO/TC 268: Sustainable Cities and Communities, also play a role in developing standards that contribute to the implementation of disaster risk reduction efforts. For example, the ISO Technical Committee ISO/TC 268, Sustainable Cities and Communities, has developed standards focusing on sustainable development objectives and indicators for cities and communities (e.g., ISO 37101, ISO 37120, ISO 37122, and ISO 37123). The ISO standards attempt to provide a common language and process used worldwide to benchmark programs; however, it is not known how many nations or programs actively use the standard as a means of benchmarking.

Standards in Emergency Management Literature

The literature on emergency management and disaster science highlights the need for further alignment to enhance emergency management capabilities (e.g., Saja, Goonetilleke, Teo, & Ziyath, 2019; Bentley & Waugh, 2005; Bowen, 2008). However, few studies have analyzed emergency management standards (e.g., Alexander, 2003; Alexander, 2005; Frykmer, 2020). The growth of emergency management has evolved reactively, whereas laws, not standards, have driven practice (McEntire, 2007; McEntire, 2008). Over time, standards and frameworks have evolved to address various issues related to the vulnerability to disasters (McEntire, 2008; Wahlström, 2015). As the field of emergency management evolves into a profession, the literature suggests that an essential element is to establish a shared identity (Cwiak, 2011; Oyola-Yemaiel & Wilson, 2005).

The implementation of international standards in emergency management has been recognized as a key factor for enhancing preparedness, response, and recovery, as well as promoting interoperability and coordination among different organizations and countries (e.g., Kapucu, Arslan, & Demiroz, 2010; Waugh & Strieb, 2006). Frameworks and standards aim to provide a roadmap for countries to effectively coordinate with all stakeholders in reducing the impacts of hazard events and preparing to respond and recover when impacts occur, while striving to promote resilience and sustainable development (Goniewicz and Burkle, 2019). However, implementing these standards and frameworks faces challenges and gaps (McEntire, 2008; Wisner and Alcántara-Ayala, 2023).

Some studies have been conducted analyzing specific standards within specific contexts, such as ISO (e.g., Lushi, Mane, & Keco, 2016; Sartor, Orzes, Touboulic, Culot, & Nassimbeni, 2019), the EMAP Standard (e.g., Jensen & Ferreira, 2022; Lucus, 2006), and the Sendai Framework (e.g., Busayo et al., 2020; Wahlstrom, 2015). These studies have highlighted the benefits of implementing standards regarding improved coordination, communication, and response capabilities. Literature also suggests that as the context of emergency management is better understood and public expectations increase, so does the interest in standards (Britton, 1999), while the existence of more consistent emergency management programs across jurisdictions suggests further evolution of the field (McEntire, 2008). In order to address these challenges and gaps, countries and organizations need to work together to develop a coherent approach to implementing emergency management and disaster risk reduction efforts.

Despite the progress made in developing international standards for emergency management, there are still challenges and gaps (Johansson and Nilsson, 2006). These gaps include a lack of consensus on definitions and terminology, varying levels of commitment and resources among countries, cultural and contextual differences that affect implementation, and the need for ongoing updates and revisions to keep up with evolving risks and technologies (Lettieri, Massella, & Radaelli, 2009). Despite the challenges in implementing international standards for emergency management, their adoption and use are crucial in enhancing proactive efforts in mitigation, prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery.

In summary, international strategy and frameworks have guided nations across the globe in focusing efforts toward a more risk-resistant world. However, implementation has been regarded as reactionary, ad-hoc, and insufficient. While implementing program-level disaster management and emergency management standards, such as EMAP and ISO, plays a crucial role, implementation in communities across the globe remains a challenge. Further analysis of the alignment of current standards in emergency management with international strategy and framework will be necessary to continue to work toward increased consistency and effectiveness in global emergency management efforts.

Methodology

This study explored the alignment of international strategy in disaster risk reduction with internationally recognized standards for emergency management programs by critically examining terminology, core concepts, and priority areas across key documents. As described in the literature review, there is a general lack of consistency and clarity in the use of terminology in research and practice related to disaster risk reduction and emergency (and disaster) management research, along with limited research on the topic. Due to the dearth of literature on the topic, this study explored alignment of one aspect (emergency management programs) of international strategy in disaster risk reduction, as categorized by the United Nations (Jacia, 2014). A qualitative methodology with an exploratory, inductive thematic analysis was used to examine the topic and answer the question: How do internationally recognized standards for emergency management programs align with international strategy in disaster risk reduction?

A review of the literature and key documents was performed to explore pertinent international-level strategies and standards involving disaster risk reduction and emergency management programs. Upon review, data collection involving international strategy was narrowed to the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015 – 2030 (Sendai Framework) and the supporting document, United Nations General Assembly Report 71/644, Report of the open-ended intergovernmental expert working group on indicators and terminology relating to disaster risk reduction (UN/GA 71/644), adopted in 2016. The two primary sources for interdisciplinary emergency management program standards that have received international recognition and are included in this study are the 1.) Emergency Management Standard (2019) by the Emergency Management Accreditation Program (EMAP Standard) and 2.) International Organization for Standardization Technical Committee 292: Security and Resilience (ISO/TC 292) standards (see Table 9). While all of the standards by ISO/TC 292 were analyzed, ISO 22300: 2021 Security and Resilience – Vocabulary (ISO 22300 Vocabulary) was predominantly used to verify specific definitions for key terms and concepts. Data was analyzed using a thematic approach to identify and compare common themes and patterns across the strategy and standards. The thematic analysis followed an iterative process of data familiarization, coding, theme development, and refinement, aiming to identify key themes and patterns. The final themes represented areas of alignment and/or divergence identified across the data and included 1.) terminology, 2.) core concepts, and 3.) priority areas. The findings present the comparison and extent of alignment.

The results of this study should be interpreted alongside potential limitations. Methodological limitations may limit the generalizability of the findings, and the inherent subjective interpretation may have introduced bias. The narrow scope of the study (emergency management programs) was necessary for the exploratory analysis on the topic, but inherently introduce potential limitations when interpreting the findings. Data collection and analysis was focused on specific standards that have received international recognition, possibly excluding relevant documents or other nation-specific standards. Furthermore, the findings did not include standards in other areas involving disaster risk reduction (e.g., sustainability, climate change, risk management). While the latest versions of documents were studied, the dynamic nature of the standards suggest that the standards will continue to evolve. To enhance rigor, the researcher employed strategies, such as detailed and contextual descriptions of the data to allow for more transferability of the findings and engaged in reflexive practices to minimize potential biases and assumptions throughout the analysis process.

Findings & Solutions

The results of the analysis present the themes and areas of alignment and divergence between the EMAP Emergency Management Standard (EMAP Standard), ISO Technical Committee 292 Standards (ISO/TC 292), and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015 – 2030 (Sendai Framework). Findings are organized into three sections: 1) terminology, 2) core concepts, and 3) priority areas. The analysis suggests similarities among the overarching themes, with widespread variation across definitions and core concepts.

Terminology

The study found considerable variations in the definitions used across key terms in the Sendai Framework (primarily retrieved from UN/GA 71/644), EMAP Standard, and ISO/TC 292 (primarily retrieved from ISO 22300 Vocabulary). Key terms explored in the analysis include hazard, risk, vulnerability, emergency, disaster, emergency management, disaster management, disaster risk reduction, crisis management, and resilience. While some variation between the documents may be expected due to the different scopes and focal points (e.g., strategy and framework compared to technical and operations standards), the extent of differences observed across key terms presents challenges and barriers to navigating how the documents relate, and the concepts built upon these key terms.

Hazard, Risk, and Vulnerability

The terms “hazard,” “vulnerability,” and “risk” are used in each of the documents analyzed. However, the definitions are not generally defined or applied consistently throughout. The most consistent definition is “hazard,” which is commonly understood as a potential source of harm or may be the cause of an incident (see Table 4). The EMAP Standard and the ISO Standards provide a broader generalization, while UN/GA 71/644 is more detailed in describing a hazard as a “process, phenomenon, or human activity” (United Nations, 2016, pg. 5). “Vulnerability” and “risk” are not defined in the EMAP Standard. However, both terms are defined in UN/GA 71/644 and ISO (see Table 4). The definitions of “vulnerability” and “risk” in UN/GA 71/644 and ISO 22300 show similarities and notable differences. For example, UN/GA 71/644 describes the “conditions” or “processes,” deliberately acknowledging the social, economic, and environmental contexts contributing to vulnerability. In contrast, ISO focuses on the probability and severity of a potential “loss,” “harm,” or “consequence.” “Risk” is only deliberately defined in the ISO standards, while UN/GA 71/644 defines “disaster risk” but not “risk” specifically.

| blank cell | UN/GA 71/644 (2016) | EMAP Standard (2019) | ISO 22300 Vocabulary (2021) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard | “A process, phenomenon or human activity that may cause loss of life, injury or other health impacts, property damage, social and economic disruption or environmental degradation” (pg. 5). | “Something that has the potential to be the primary cause of an incident” (pg. 4). | “Source of potential harm. Note: Hazard can be a risk source” (pg. 14). |

| Vulnerability | “The conditions determined by physical, social, economic and environmental factors or processes which increase the susceptibility of an individual, a community, assets or systems to the impacts of hazards” (pg. 24). | Not defined. | Vulnerability analysis: “process of identifying and quantifying something that creates susceptibility to a source of risk that can lead to a consequence” (pg. 37). Community vulnerability: “characteristics and conditions of individuals, groups or infrastructures that put them at risk for the destructive effects of a hazard” (pg. 6). |

| Disaster Risk | “The potential loss of life, injury, or destroyed or damaged assets which could occur to a system, society or a community in a specific period of time, determined probabilistically as a function of hazard, exposure, vulnerability and capacity” (pg. 14). | Not defined. | Risk: “effect of uncertainty on objectives” (pg. 27). |

Emergency and Disaster

The definitions and use of the terms “emergency” and “disaster” vary across the documents; however, there is a common generalization depicted (see Table 5). Contextually, UN/GA 71/644 focuses more on a “community or society” (2016, pg. 13), while the EMAP Standard and ISO apply to a community or organization. “Emergency” and “disaster” in the EMAP Standard and ISO Standard are similarly differentiated by the “severity” or “widespread” implications on “life” or “human,” “property” or “material,” “economic,” “environmental,” and/or “critical systems,” where disasters are more severe. UN/GA 71/644, comparatively, differentiates “emergency” and “disaster” based on the severity of the event and the cause of “serious disruption” and specifically incorporates the conditions related to “exposure, vulnerability, and capacity” within the definition (2016, pg. 13). UN/GA 71/644 specifically highlights how the terms “emergency” and “disaster” are often used interchangeably (2016, pg. 13).

| blank cell | UN/GA 71/644 (2016) | EMAP Standard (2019) | ISO 22300 Vocabulary (2021) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency | “Is sometimes used interchangeably with the term disaster, as, for example, in the context of biological and technological hazards or health emergencies, which, however, can also relate to hazardous events that do not result in the serious disruption of the functioning of a community or society” (pg. 13). | “An incident or set of incidents, natural or human-caused, that requires responsive actions to protect life, property, the environment, and/or critical systems” (pg. 4). | “Sudden, urgent, usually unexpected occurrence or event requiring immediate action” (pg. 12). |

| Disaster | “A serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society at any scale due to hazardous events interacting with conditions of exposure, vulnerability and capacity, leading to one or more of the following: human, material, economic and environmental losses and impacts” (pg. 13). | “A severe or prolonged emergency that threatens life, property, the environment, and/or critical systems” (pg. 4). | “Situation where widespread human, material, economic or environmental losses have occurred that exceeded the ability of the affected organization, community, or society to respond and recover using its own resources” (pg. 10). |

Emergency Management, Disaster Management, Disaster Risk Reduction, & Crisis Management

Considerable differences were observed across the documents for the terms “emergency management,” “disaster management,” “disaster risk reduction,” and “crisis management.” For example, the terms “disaster risk reduction” and “disaster management” are only defined in UN/GA 71/644, and “crisis management” is only defined in ISO 22300 and focuses on the organizational level (see Table 6). “Emergency management” is defined in UN/GA 71/644 and ISO 22300, while the EMAP Standard specifically focuses on an “emergency management program.” The EMAP Standard and ISO 22300 include the phases of “prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery” in “emergency management” and “emergency management program,” while the EMAP Standard also includes “mitigation.” UN/GA 71/644 includes the phases of “preparedness, response, and recovery” in both “emergency management” and “disaster management,” however, the terms are differentiated by the level of disruption to society while also acknowledging that the terms are often used interchangeably.

| blank cell | UN/GA 71/644 (2016) | EMAP Standard (2019) | ISO 22300 Vocabulary (2021) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disaster management | “The organization, planning and application of measures preparing for, responding to and recovering from disasters” (pg. 14). | Not defined. | Not defined. |

| Emergency management | “Used, sometimes interchangeably, with the term disaster management, particularly in the context of biological and technological hazards and for health emergencies. While there is a large degree of overlap, an emergency can also relate to hazardous events that do not result in the serious disruption of the functioning of a community or society” (pg. 14). | Emergency Management Program: “A system that provides for management and coordination of prevention, mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery activities for all hazards. The system encompasses all organizations, agencies, departments, and individuals having responsibilities for these activities” (pg. 4). | “Overall approach for preventing emergencies and managing those that occur” (pg. 12). “In general, emergency management utilizes a risk management approach to prevention, preparedness, response and recovery before, during and after potentially destabilizing events and/or disruptions” (pg. 12). |

| Disaster risk reduction | “Aimed at preventing new and reducing existing disaster risk and managing residual risk, all of which contribute to strengthening resilience and therefore to the achievement of sustainable development” (pg. 16). | Not defined. | “Policy aimed at preventing new and reducing existing disaster risk and managing residual risk, all of which contribute to strengthening resilience and therefore to the achievement of sustainable development” (pg. 10). |

| Crisis management | Not defined | Not defined. | “Holistic management process that identifies potential impacts that threaten an organization and provides a framework for building resilience, with the capability for an effective response that safeguards the interests of the organization’s key interested parties, reputation, brand and value-creating activities, as well as effectively restoring operational capabilities” (pg. 9). |

Resilience

“Resilience” is similarly defined in UN/GA 71/644 and ISO 22300; however, the term is not included in the EMAP Standard (see Table 7). The context of the definition for UN/GA 71/644 is a “system,” while ISO 22300 provides a more focused definition for “an urban system.” The commonality between the two definitions is the ability to “absorb” effects or shocks and to “adapt.” The term, however, is differentiated between the two documents by the focus. UN/GA 71/644 highlights “preservation and restoration of essential basic structures and functions,” while ISO 22300 focuses on the “capacity to anticipate, prepare and respond” (2021, pg. 26).

| blank cell | UN/GA 71/644 (2016) | EMAP Standard (2019) | ISO 22300 Vocabulary (2021) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resilience | “The ability of a system, community or society exposed to hazards to resist, absorb, accommodate, adapt to, transform and recover from the effects of a hazard in a timely and efficient manner, including through the preservation and restoration of its essential basic structures and functions through risk management” (pg. 22). | Not defined. | “Ability to absorb and adapt in a changing environment” (pg. 26). “In the context of urban resilience the ability to absorb and adapt to a changing environment is determined by the collective capacity to anticipate, prepare and respond to threats and opportunities by each individual component of an urban system” (pg. 26). |

Core Concepts

The document analysis revealed two core concepts explored in this study, the disaster cycle and disaster phases, representing elements of the disaster cycle. The specific terms “disaster cycle,” “emergency management cycle,” “disaster management cycle,” and “disaster risk reduction cycle” did not appear in the documents, but the concept of continual and cyclical considerations for disaster, organized by phases, consistently appeared. The findings suggest that although there were widespread conceptual similarities across the Sendai Framework, EMAP Standard, and ISO/TC 292, the extent of differences provides challenges and barriers toward a common understanding and application of the core concepts.

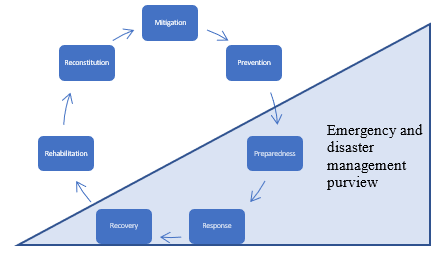

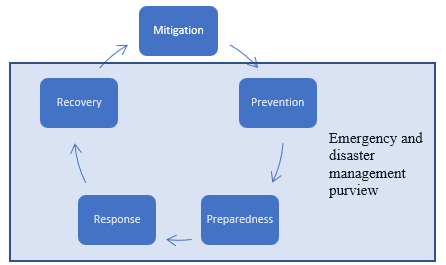

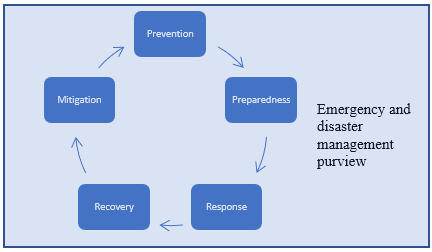

Disaster Cycle

Alignment was not observed in depicting the phases within the disaster cycle (i.e., emergency management cycle, disaster management cycle). Although there were some similarities in the phases across the data, each source had a different representation of the disaster cycle (see Visuals 1-3). Similarly, the phases “prevention,” “preparedness,” “response,” and “recovery” were included in the Sendai Framework, EMAP Standard, and ISO/TC 292. In contrast, “mitigation” was included in the Sendai Framework and EMAP but not ISO. The Sendai Framework uniquely includes the phases of “rehabilitation” and “reconstitution.” A glaring difference appears within the purview of emergency and disaster management; where the EMAP standard considered the entire disaster cycle a part of emergency management programs (Visual 3), the Sendai Framework and ISO/TC 292 did not include “prevention” or “mitigation” as part of emergency or disaster management (Visual 1).

Visual 1. Sendai Framework Disaster Cycle & Emergency Management Nexus

Visual 2. ISO/TC 292 Disaster Cycle & Emergency Management Nexus

Visual 3. EMAP Standard Disaster Cycle & Emergency Management Nexus

Visual 3. EMAP Standard Disaster Cycle & Emergency Management Nexus

Figure 1. Representations of the Disaster Cycle

Disaster Phases

The phases included in the disaster cycle varied in their definitions. However, there were conceptual similarities observed in many phases depicted across the documents reviewed (i.e., mitigation, prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery) (see Table 8). For example:

- Mitigation is generally considered to “minimize,” “lessen,” “reduce,” or “limit,” or “eliminate” “impacts” or “consequences” from “hazardous events” or “incidents.”

- Prevention encompasses “measures” or “activities” to “avoid,” “stop,” or “limit” occurrence or impact of the event.

- Preparedness can be considered “activities” to “anticipate” or “enhance” readiness and improve other phases.

- Response includes the “immediate” and “short-term” actions focused on “life,” “property,” “environment,” and “critical” systems or assets.

- Recovery reflects the “restoring” or “improving” of “livelihoods” in areas affected by disaster.

- Rehabilitation and reconstitution are presented as distinct phases from recovery as part of a build–back better concept in the Sendai Framework and are specifically defined in UN/GA 71/644 (see Table 8).

Although conceptual similarities are observed in the disaster phases, the extent of differences in the context and specific definitions presents challenges to “neatly” crosswalk the concepts.

| blank cell | UN/GA 71/644 (2016) | EMAP Standard (2019) | ISO 22300 Vocabulary (2021) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mitigation | “The lessening or minimizing of the adverse impacts of a hazardous event” (pg. 20). | “The activities designed to reduce or eliminate risks to persons or property or to lessen the actual or potential effects or consequences of a disaster. Mitigation involves ongoing actions to reduce exposure to, probability of, or potential loss due to hazards” (pg. 5). | “Limitation of any negative consequence of a particular incident” (pg. 20). |

| Preparedness | “The knowledge and capacities developed by governments, response and recovery organizations, communities and individuals to effectively anticipate, respond to and recover from the impacts of likely, imminent or current disasters” (pg. 21). | “The range of deliberate, critical tasks and activities necessary to build, sustain, and improve the operational capability to prevent, protect against, mitigate against, respond to, and recover from disasters. Preparedness is a continuous process” (pg. 5). | “Readiness activities, programmes, and systems developed and implemented prior to an incident that can be used to support and enhance prevention, protection from, mitigation of, response to and recovery from disruptions, emergencies or disasters” (pg. 23). |

| Prevention | “Activities and measures to avoid existing and new disaster risks” (pg. 21). | “Actions to avoid an incident or to intervene to stop an incident from occurring. Prevention involves actions to protect lives, property, the environment, and critical systems/infrastructure. It involves identifying and applying intelligence and other information to a range of activities that may include such countermeasures as deterrence operations; heightened inspections; improved surveillance and security operations; investigations to determine the full nature and source of the threat; public health and agricultural surveillance and testing processes; immunizations, isolation, or quarantine; and, as appropriate, specific law enforcement operations aimed at deterring, preempting, interdicting, or disrupting illegal activity, and apprehending potential perpetrators.” (pg. 5). | “Measures that enable an organization to avoid, preclude or limit the impact of an undesirable event or potential disruption” (pg. 23). |

| Response | “Actions taken directly before, during or immediately after a disaster in order to save lives, reduce health impacts, ensure public safety and meet the basic subsistence needs of the people affected. Annotation: Disaster response is predominantly focused on immediate and short term needs and is sometimes called disaster relief. Effective, efficient and timely response relies on disaster risk-informed preparedness measures, including the development of the response capacities of individuals, communities, organizations, countries and the international community.” (pg. 22). |

“Efforts to minimize the short-term direct effects of an incident threatening life, property, the environment, and/or critical systems” (pg. 5). | Response plan: “documented collection of procedures and information that is developed, compiled and maintained in preparedness for use in an incident” (pg. 27). Response Programme Plan: “processes, and resources to perform the activities and services necessary to preserve and protect life, property, operations and critical assets” (pg. 27). |

| Build back better | “The use of the recovery, rehabilitation and reconstruction phases after a disaster to increase the resilience of nations and communities through integrating disaster risk reduction measures into the restoration of physical infrastructure and societal systems, and into the revitalization of livelihoods, economies and the environment” (pg. 11). | Not defined. | Not defined. |

| Reconstruction | “The medium- and long-term rebuilding and sustainable restoration of resilient critical infrastructures, services, housing, facilities and livelihoods required for the full functioning of a community or a society affected by a disaster, aligning with the principles of sustainable development and “build back better”, to avoid or reduce future disaster risk” (pg. 21). | Not defined. | Not defined. |

| Recovery | “The restoring or improving of livelihoods and health, as well as economic, physical, social, cultural and environmental assets, systems and activities, of a disaster affected community or society, aligning with the principles of sustainable development and “build back better”, to avoid or reduce future disaster risk” (pg. 21). | “The development, coordination, and execution of plans or strategies for the restoration of impacted communities and government operations and services through individual, private sector, non-governmental, and public assistance” (pg. 5). | “Restoration and improvement, where appropriate, of operations, facilities, livelihoods or living conditions of affected organizations, including efforts to reduce risk factors” (pg. 26). |

| Rehabilitation | “The restoration of basic services and facilities for the functioning of a community or a society affected by a disaster” (pg. 22). | Not defined. | Not defined. |

Priority Areas

This section explored the alignment of themes from the standard elements from the EMAP Standard and ISO/TC 292 (related to “emergency management”) with the Sendai Framework’s priority areas. Recall the Sendai Framework includes the priority areas: 1) understanding risk, 2) strengthening disaster risk governance, 3) investing in disaster risk reduction, and 4) enhancing preparedness for effective response and to “Build Back Better” in recovery, rehabilitation, and reconstruction. A common element across the priority areas and program elements was the emphasis on proactive steps and comprehensive planning across the phases of the disaster cycle. Although there are similarities in the themes across the documents reviewed, the analysis did not provide a well-ordered alignment (see Table 9). The differences in what is considered within the purview of emergency and disaster management, as shown in Figure 1, are highlighted when comparing these elements. For example, many elements described within the EMAP Standard as pertaining to “emergency management programs” are included within the “disaster risk reduction” umbrella in the Sendai Framework and incorporate standards specific to ISO Technical Committee 268: Sustainable Cities and Communities (ISO/TC 268) (see Table 9).

|

Sendai Framework Priority Areas (Sendai Framework, 2015) |

EMAP Standard – Program Elements (EMAP, 2019) |

ISO/TC 292 Published Standards (ISO/TC 292, 2024) |

|---|---|---|

|

Understanding risk |

|

|

|

Strengthening disaster risk governance |

|

|

|

Investing in disaster risk reduction |

|

|

|

Enhancing preparedness for effective response and to “Build Back Better” in recovery, rehabilitation, and reconstruction |

|

|

In summary, while there are similarities in the Sendai Framework, EMAP Standard, and ISO/TC 292 Standards, and some variations may be attributed to differences in the scope and audience of the documents, the extent of the differences would make it challenging for anyone attempting to cohesively apply the practices or to research the topic holistically. Similar terms were used across the strategy and standards; however, this study found differences in how the terms were defined and applied. Furthermore, variations in the disaster cycle and what is considered in the purview of emergency (and disaster) management provide further barriers to applying core concepts. Although an alignment could be observed between the priority areas of the Sendai Framework and the elements of the EMAP Standard and ISO/TC 292 Standards, a well-ordered alignment was not observed. It is important to note that an emphasis on taking proactive steps and developing comprehensive strategies throughout the disaster cycle phases was evident.

Discussion

The fields of disaster risk reduction and emergency (and disaster management) have primarily evolved through reactions to the impacts of hazard events, which set conditions for siloed and fragmented approaches to emerge (McEntire et al., 2002). This lack of alignment has hindered effective coordination and collaboration across the phases of the disaster cycle in both research and practice. Furthermore, misalignment has added challenges in navigating the body of knowledge in the field and in synthesizing vital information. To address these challenges there must be interdisciplinary effort to further align key terms, core concepts, and priority areas.

Analysis of Findings

The findings suggest conceptual confusion involving key terms, core concepts, and priority areas related to the nexus of emergency (and disaster) management and disaster risk reduction. Across strategy and standards, consistency in how terms were defined and how concepts were applied was not widely observed. While there is a clear emphasis on being proactive in limiting impacts and comprehensively planning for the impacts to hazard events across phases, navigating concepts across the documents was challenging. It was evident in the analysis that there is a lack of common understanding of the meaning “emergency management,” “disaster management,” and “disaster risk reduction.” Furthermore, using the same terms in different contexts and applications provided further confusion in attempting to establish a consistent understanding and alignment. The variations of the disaster phases and described role of emergency management add challenges for nations, communities, organizations, and other programs in navigating and implementing best practices. The gaps presented in the findings pose implications for research and practice in emergency management, disaster management, and disaster risk reduction.

Implications of Finding

The lack of consistency in understanding key terms in emergency management and disaster risk reduction has significant scholarly and practical implications. The lack of clarity for both research and practice hinders the ability to compare and synthesize findings from different studies, guiding documents, after-action reports, and initiatives. Individuals across communities, organizations, and nations must navigate a compendium of differing, and at times conflicting, key terms and concepts, resulting in conceptual confusion, which may result in misinterpretation and hinder application.

Scholarly pursuits are considerably impacted by the lack of consistency. As research in disaster science and emergency management are interdisciplinary in nature, where individuals from various fields contribute to the knowledge base, a common understanding enhances collaboration among scholars and the integration of findings (Jensen, 2010; Staupe-Delgado, 2019). Acute disasters can raise interest in research across disciplines, which is vital in expanding the body of knowledge, but hindered by difficulty navigating the field. Key findings may be overlooked without clarity of terms and concepts. Conceptual clarity is essential to advance interdisciplinary research and advance toward transdisciplinary understanding

Practical implications for the findings apply across sectors, levels, and nations. Without a consistent understanding of what specifically constitutes “emergency management” or a common language from which to approach core concepts, the applications of effective programs become more challenging. Lessons learned, and best practices applied from one sector, jurisdiction, or nation, may be misunderstood due to conceptual differences, which may lead to misapplication of initiatives. A lack of consistency in the benchmarking documents may result in key differences in policy, adding further barriers to individuals and programs attempting to implement practices that have proven effective elsewhere. The cross-functional nature of emergency management, along with concepts associated with sustainable development, resilience, and climate change, further complicates a path toward consistency and harmonization of strategies and standards across programs around the globe responsible for emergency management and disaster risk reduction.

Review of Lessons Learned

The findings highlight the need for greater attention to define and standardize key terms in emergency management and disaster risk reduction. Although there has been progress in international strategy to promote a proactive stance to address risk, vulnerability, and the impacts of hazards, the lack of consistency hinders progress in the field across practical and scholarly pursuits. To effectively foster collaboration and integration of findings, interdisciplinary conceptual clarity must be achieved.

Recommendations

Scholarly and practical recommendations are provided to address the implications of the study. Although further coalescing around definitions and core concepts will be challenging and will require participation from individuals across fields worldwide, the progress made to promote a “safer world” demonstrates the ability of the global community to work towards common goals and establish common frameworks. A holistic approach involving research and practice can further evolve global practices in emergency management and disaster risk reduction.

Scholarly Recommendations

Scholarly recommendations based on the findings of the study are centered around further coordination and collaboration by researchers to synthesize the body of knowledge and coalesce around key terms in sync with the international and practitioner community. A foundation of interdisciplinary research in disaster science and emergency management has been established, but further coordination across nations may help academic communities center around an agreed-upon body of knowledge. At the minimum, a crosswalk of terms and concepts should be established to facilitate a common understanding and effective communication among researchers. Additional scholarly recommendations include:

- Adopting standard definitions for “emergency,” “disaster,” and “catastrophe” across disciplines, which could further be adopted by practice (e.g., Montano & Savitt, 2023; Quarantelli, 1998; Quarantelli, 2006).

- Advancing the use of theory in emergency management research (e.g., Drabek, 2005; Jensen, 2010; McEntire, 2005).

- Comparing concepts related to international frameworks and guidance, such as sustainable development, resilience, climate change, and humanitarian assistance, will further support the development of a crosswalk of terms to clarify concepts necessary across fields.

- Furthering the study of the local to global alignment of the Sendai Framework, standards, and guidance documents used across different countries, including different levels of jurisdictions and across all sectors, will further understanding of the state of practice.

- Conducting research on the use of terms and concepts within national-level policy, laws, frameworks, and strategies to better understand the breadth of differences in applications and to determine what benchmarks are being used to influence policy.

- Exploring the effectiveness of current international agreements and strategies in emergency management and disaster risk reduction to identify and support enhancement of strategies and guidance.

Working toward achievement of these scholarly recommendations will help unify a body of knowledge and support practical applications.

Practical Recommendations

Practical recommendations are focused on establishing solutions to increase the ability of individuals worldwide to quickly learn about the field, understand core concepts, differentiate contexts in which best practices are applied, and effectively find and apply best practices and lessons learned. Specific practical recommendations include:

- Developing consistent terminology, definitions, and processes for international emergency and disaster management or, at minimum, provide a clear crosswalk of terms, concepts, and guiding documents that can be easily applied across sectors and local and global communities.

- Coalescing around professional terms, such as the concepts of “emergency management,” “disaster management,” “crisis management,” and “disaster risk reduction.”

- Establishing a global platform for sharing best practices, lessons learned, and case studies in emergency and disaster management to facilitate knowledge exchange and collaboration among practitioners, which encourages alignment across nations and communities.

- Encouraging nations, communities, and organizations to further apply a continuous improvement process to regularly review and update practices based on standards and benchmarks.

Without clear and consistent boundaries for the body of knowledge, the influence of outside factors in shaping the field, such as politics or the latest trend, only grows, rather than what has been learned from research and practice (McEntire, 2007; Waugh & Strieb, 2006). As emergency and disaster management emerges as a discipline and profession, the field must adapt to new and growing challenges, including having a monopoly on the specialized body of knowledge and autonomy over standards (Cwiak, 2011; Oyola-Yemaiel & Wilson, 2005).

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest confusion around concepts related to disaster risk reduction and emergency (and disaster) management being used internationally, which exacerbate current and emerging issues for the field. While strategies and standards provide frameworks and benchmarks for the development of emergency management programs, conceptual clarity remains elusive. There is a clear need for further consistency in the understanding and use of core concepts in research and practice. The contributions of this chapter could promote further alignment and enhance disaster practices at local, national, and international levels. Furthermore, alignment can bolster accountability by setting clear and consistent benchmarks for programs to achieve. To move forward, the international community must coalesce around core concepts and solidify key terms across disciplines to further a unified body of knowledge.

References

Alexander, D. (2003). Towards the development of standards in emergency management training and education. Disaster Prevention and Management, 12(2), 113–123. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.lib.ndsu.nodak.edu/10.1108/09653560310474223

Alexander, D. (2005). Towards the development of a standard in emergency planning. Disaster Prevention and Management, 14(2), 158–175. https://doi.org/10.1108/09653560510595164

Bentley, E., & Waugh, W. L. (2005). Katrina and the necessity for emergency management standards. Journal of Emergency Management, 3(5), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.5055/jem.2005.0043

Bowen, A. A. (2008). Are we really ready? The need for national emergency preparedness standards and the creation of the cycle of emergency planning. Politics & Policy, 36(5), 834–853. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-1346.2008.00137.x

Britton, N. (1999). Whither the emergency manager? International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 17(2), 223–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/0280727099017002

Bullock, J., Haddow, G., & Coppola, D. (2020). Introduction to emergency management. Butterworth-Heinemann. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2018-0-00417-X

Burkle, F M., Isaac-Renton, J., Beck, A T., Belgica, C P., Blatherwick, J., Brunet, L A., Hardy, N., Kendall, P., Kunii, O., Lokey, W., Sansom, G., & Stewart, R D. (2001, March 1). Theme 5. Application of international standards to disasters: Summary and Action Plan. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1049023x00025541

Busayo, E. T., Kalumba, A. M., Afuye, G. A., Ekundayo, O. Y., & Orimoloye, I. R. (2020). Assessment of the Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction studies since 2015. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 50, 101906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101906

Coppola, D. (2021). Introduction to International Disaster Management. Elsevier Science. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2018-0-00377-1

Cwiak, C. (2011). Framing the future: What should emergency management graduates know? Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, 8(2). https://doi.org/10.2202/1547-7355.1910

Delshad, V., Pourvakhshoori, N., Rajabi, E., Bazyar, J., Ahmadi, S., & Khankeh, H R. (2020, October 1). International agreements on disaster risk management based on world conferences, successful or not: A review study. Health in Emergencies and Disasters Quarterly 2020, 6(1): 1-8. https://doi.org/10.32598/hdq.6.1.38.4

Drabek, T. E. (2005). Theories relevant to emergency management versus a theory of emergency management. Journal of Emergency Management, 3(4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.5055/jem.2005.0040

Emergency Management Accreditation Program (EMAP). (2019). Emergency Management Standard: ANSI/EMAP EMS 5-2019. Retrieved from https://emap.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/EMAP_2019_Emergency_Management_Standard_.pdf

Frykmer, T., & Candidate, P. (2020). “What’s the problem?”—Toward a framework for collective problem representation in emergency response management. Journal of Emergency Management, 18(6), Article 6. https://doi.org/10.5055/jem.2020.0504

Goniewicz, K., & Burkle, F M. (2019). Challenges in implementing Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction in Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(14), 2574-2574. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142574

ISO/TC 292 (retrieved 2024). Published Standards. ISO/TC 292 Online. International Organization for Standardization. Retrieved from: https://www.isotc292online.org/published-standards/

ISO (2021). ISO 22300:2021: Security and resilience – Vocabulary. International Organization for Standardization. Retrieved from: https://www.iso.org/standard/77008.html

Jachia, L. (2014). Standards and normative mechanisms for disaster risk reduction (Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction). United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. https://www.preventionweb.net/english/hyogo/gar/2015/en/bgdocs/UNECE,%202014.pdf

Jensen, J. (2010). Emergency management theory: Unrecognized, underused, and underdeveloped. Integrating Emergency Management Studies into Higher Education: Ideas, Programs, and Strategies. Public Entity Risk Institute. ISBN 978-0-9793722-4-7

Jensen, J., Ferreira, M. (2023). An exploration of local emergency management program accreditation pursuit. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management. De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/jhsem-2022-0019

Johansson, M., & Nilsson, P. (2006). Towards international emergency management standards. LUTVDG/TVBB–5215–SE. Lund University. Retrieved from http://lup.lub.lu.se/student-papers/record/1767524/file/1769517.pdf

Kapucu, N., Arslan, T., & Demiroz, F. (2010). Collaborative emergency management and national emergency management network. Disaster Prevention and Management, 19(4), 452-468. https://doi.org/10.1108/09653561011070376

Lettieri, E., Masella, C., & Radaelli, G. (2009). Disaster management: Findings from a systematic review. Disaster Prevention and Management, 18(2), 117-136. https://doi.org/10.1108/09653560910953207

Lucus, V. (2006). A history of the Emergency Management Accreditation Program (EMAP). Journal of Emergency Management, 4(5), 75–79. ISSN 1543-5865; 2374-8702

Lushi, I., Mane, A., & Keco, R. (2016). A literature review on ISO 9001 standard. European Journal of Business, Economics and Accountancy. ISSN 2056-6018

McEntire, D. A., Fuller, C., Johnston, C. W., & Weber, R. (2002). A comparison of disaster paradigms: The search for a holistic policy guide. Public administration review, 62(3), 267-281. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6210.00178

McEntire, PhD, D. A. (2005). Emergency management theory: Issues, barriers, and recommendations for improvement. Journal of Emergency Management, 3(3), 44. https://doi.org/10.5055/jem.2005.0031

McEntire, PhD, D. A. (2007). The historical challenges facing emergency management and homeland security. Journal of Emergency Management, 5(4), 17. https://doi.org/10.5055/jem.2007.0011

McEntire, D. A. (2008). A critique of emergency management policy: Recommendations to reduce disaster vulnerability. International Journal of Public Policy, 3(5-6), 302-312. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPP.2008.020984

McEntire, D. A. (2018). Learning more about the emergency management professional. FEMA Higher Education Program, 50.

Montano, S., & Savitt, A. (2023). Revisiting emergencies, disasters, & catastrophes: Adding duration to the hazard event classification. International Journal of Mass Emergencies & Disasters, 41(2-3), 259-278. https://doi.org/10.1177/02807270231211831

Oyola-Yemaiel, A., & Wilson, J. (2005). Three essential strategies for emergency management professionalization in the U. S. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 23(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1177/028072700502300105

Quarantelli, E. L. (Ed.). (1998). What is a disaster?: Perspectives on the question. Psychology Press. ISBN 0415178991, 9780415178990

Quarantelli, E. L. (2006). Catastrophes are different from disasters: Some implications for crisis planning and managing drawn from Katrina. Social Science Research Council. Retrieved from https://items.ssrc.org/understanding-katrina/catastrophes-are-different-from-disasters-some-implications-for-crisis-planning-and-managing-drawn-from-katrina/

Sartor, M., Orzes, G., Touboulic, A., Culot, G., & Nassimbeni, G. (2019). ISO 14001 standard: Literature review and theory-based research agenda. Quality Management Journal, 26(1), 32–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/10686967.2018.1542288

Saja, A. M. A., Goonetilleke, A., Teo, M., & Ziyath, A. M. (2019). A critical review of social resilience assessment frameworks in disaster management. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 35, 101096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101096

Shiley, D. (2018). News release: IAEM endorses EMAP as the etandard for emergency management programs. International Association of Emergency Managers (IAEM).

Staupe‐Delgado, R. (2019). Analysing changes in disaster terminology over the last decade. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 40, 101161-101161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101161

Stratton, S J. (2017). Tools for disaster research in the model of the Sendai Framework. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 32(3), 233. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1049023x17006483

United Nations. (1987). International Decade for Disaster Risk Reduction (General Assembly Resolution 42/169). Retrieved from https://www.unisdr.org/files/resolutions/42_169.pdf

United Nations. (1994). Yokohama Strategy and Plan of Action for a Safer World. Retrieved from https://www.preventionweb.net/files/8241_doc6841contenido1.pdf