16 Applications and Prospects of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Emergency Situations: A Case Study from Taiwan

Hsin-Hsuan “Shel” Lin, SJD and Yi-En “Mike” Tso, PhD.

Authors

Hsin-Hsuan Lin, Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan

Yi-En Tso, Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, Soochow University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Keywords

unmanned aerial vehicle, drone, damage assessment, legal regulation

Abstract

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) or drones have been introduced to the process of emergency management to enhance efficiency in damage assessment, data collection, and decision-making. Legislation governing drone use impacts multifaceted areas, including effectiveness, privacy, public safety, and national security. However, the legislation of using these technologies in disaster response and recovery may be diminished by the lack of standards or consensus on operational concepts, definitions, and regulations that address operations and operator qualifications. In consideration of this issue, this chapter addresses how countries use UAVs and establish regulations for drone operation and data collection. With Taiwan as an example, the analysis focuses on how drones are used in damage assessment and how basic rights are protected in the collection of personal data. Taiwan is then compared with European Union countries with robust regulatory frameworks for protecting personal data during drone use. Suggestions are then formulated for Taiwan and other nations to enable these countries to foster responsible drone usage, in which personal data are collected in accordance with democratic values.

Introduction

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAS) encompass a combination of modalities operated without a pilot on board, along with associated components such as control stations. These systems come in two primary modalities: remotely piloted from a different location (remotely piloted aircraft systems) and fully autonomous, programmed UASs. Both modalities can be combined in a single UAS (Du & Heldeweg, 2019).

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) or drones possess sensing, decision-making, and control capabilities and are driven through remote control, automatic guidance, or autonomous navigation. Their use in emergency operations by public sectors has been rapidly evolving for a number of reasons. Compared with conventional vehicles, drones reduce risks of injury and are less constrained by human limitations. For example, drones can be controlled remotely in fire accident locations where the drone operator’s safety can be ensured. Drones can be operated for extended periods to execute tasks such as transportation, data collection, surveillance, and help capture and communicate needed information (Samad, Bay and Godbole, 2007). The use of drones not only enhances the socioeconomic benefits and efficiency of labor-intensive inspections but also improves the accuracy of administrative decision-making by collecting image data with lower costs and higher resolution. The application of drones in disaster relief situations is particularly advantageous, as they can accelerate response times. Drone fleets can simultaneously monitor disaster situations, airdrop supplies, and transport critical medical supplies, among other functions.

In recent years, UAVs have aided the collection of accurate data during or after disasters. They can also help public sector officials and citizens adequately prepare for incoming disasters by tracking advanced information and alerts. Their effectiveness in implementing real-time aerial imagery and surveillance enhances possibilities for live tracking to comprehend situations on the ground. In emergency management, drones are most commonly used to detect structural stability, evaluate disasters, assess situations remotely, map locations, deliver urgently needed supplies, extinguish fires, and airlift victims (Glantz et al., 2020; Equinox’s Drones, 2023). In Australia, drones are used to collect images and spatial data for assessing damage, rapidly providing assistance to disaster victims, mapping to restore services, and delivering supplies. For example, 218 drone flights were carried out to help the Australian government map and assess damage during recovery works conducted after flooding in Queensland and New South Wales (Australia Government, 2024). In Vietnam, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) has equipped six central provinces with drones since 2022, and trained staff use the drones to collect aerial data in flooding areas and other disaster areas for damage assessment. After disaster, drones can be used to survey the damage of the disaster to enhance the decision making in recovery works and future disaster mitigation (Hilson, 2024). Drones have also been useful and reliable in data collection and analysis during recovery works (UNDP, 2024). Finally, they enable safe, efficient, and excellent search and rescue operations, thereby advancing situational awareness, the mapping of large areas, and search and rescue efforts.

The problem, however, is that the legality and legitimacy of using drones in emergency management may be diminished by the lack of standards or consensus on operational concepts, definitions, and regulations that address operations and operator qualifications. This deficiency is compounded by poor record-keeping about reliability, which considerably increases insurance and liability costs (Glantz et al., 2020). Drones’ reliability of usage and data collection is frequently threatened by environment conditions such as clouds, fog, heavy rain, and severe weathers (Mohsan et al. 2023).

These challenges can be addressed through an extensive review of missions and goals, executive support, and comprehensive programmatic information on drone programs that includes the understanding of information needs, the awareness of comparative programs, the potential uses of drones in disaster response, and barriers to the formal integration of drones into national airspace systems (Glantz et al., 2020). Such initiatives are necessary for the executive and legislative branches of government to create a robust system of drone operations (Glantz et al., 2020). Moreover, the increasing use of drones in disaster response and recovery has encouraged research and development of the drone industry. An increasing number of manufacturers join in the industry to offer drones with higher accuracy in data collection and lower costs in production and maintenance. However, such usage for the collection of spatial and aerial data may be confronted with privacy and regulation issues (e.g., the acquisition of information from private properties and monitoring of citizen’s locations and actions without their permission) (Majeed et al., 2021). These concerns also vary in different countries, thus casting doubt on the sufficiency of the security of these technologies (Restrepo, 2024).

Effective laws ensure safe integration, protect privacy, and manage airspace, preventing misuse and accidents calibrate a comprehensive framework for responsible drone usage. Nonetheless, the regulatory frameworks in Taiwan governing their operations, functionalities, and management have been confronted with difficulties in keeping pace with this burgeoning trend. These regulations will require continued revisions and adaptations to ensure their efficacy and relevance amid the ongoing rapid evolution of UAS technology and equipment (Du & Heldeweg, 2019). The failure to create well-established legislation that covers drone operation, data gathering, and data usage may pose threats to human rights. The utilization of drone data across various fields lacks a unified strategy, resulting in numerous drone users developing and implementing their own regulatory frameworks, methodologies, and systems. Taiwan, for instance, introduced the Unmanned Drone Technology Innovation Experimental Act in 2018. Modern countries, such as European Union (EU) nations, have also adopted regulations on data and information gathering, analysis, and usage. In these countries, drone pilots are required to obey strict data privacy laws. Furthermore, how to use drone data in the decision-making process remains ambiguous in the humanitarian sector (American Red Cross, 2024).

With this introduction in mind, it is important to explore how a robust and secure environment for innovation can be established, ensuring that the necessary infrastructure is promptly put in place to support disaster relief efforts. In this article, an analysis of legislation and scholarly discussions surrounding UASs is carried out to shed light on the potential and limitations of UAVs. A literature review and brief introduction of method used in this chapter are followed by discussions of how drones are used in disaster response and issues about privacy and basic rights protection. Having a robust institution environment of drone usage and basic right protection will undoubtedly enhance the responsible use of such novel technology in the future.

Literature Review

In the realm of drone technology, there has been a focus on establishing disaster prevention and relief policies with a human-centric approach (Rabta et al., 2018). Emphasis has also been placed on enhancing the effectiveness of using drones in data collection through the incorporation of advanced mechanical systems for detection and information gathering (Kyrkou & Theocharides, 2019). Drones can be categorized into two distinct groups by functions and applications: relaying and sensing UAVs. Relaying UAVs are mobile technologies intended to help establish an emergency communication network that facilitates information exchange between disaster areas and beyond (Zhang et al., 2023). Sensing UAVs are devices with different sensors that aid the collection of remote sensing data at fewer costs than those incurred using commercial satellites (Zhang & Zhu, 2023). These drones fall under a UAV network, which has a hierarchical management structure, with a central controller responsible for assigning tasks to drones based on available resources and defining operational areas according to the priority accorded to affected regions (Shamsoshoara et al., 2020).

Drone and robot management can also be carried out through an iterative regulatory approach, which is aimed at coordinating and aligning efforts between developers and regulatory bodies (Fosch-Villaronga & Heldeweg, 2018). The need for such an approach highlights the current lack of a mechanism for effective governance, leading to a disconnect between research and regulatory activities in robotics. Fosch-Villaronga and Heldeweg (2018) introduced a theoretical model for enhancing coordination, drawing on the literature to explore alignment modes and iterations for closer collaboration. They cautioned against merely establishing coordinating agencies without formalizing communication, advocating for an iterative process that covers impact assessments, evaluation settings, and legislative reviews. The model, which emphasizes evidence-based policies adaptable to evolving technologies, is designed to bridge the gap between government approaches and the demands of ethical oversight (Fosch-Villaronga & Heldeweg, 2018).

The legal framework governing drone usage in the European Union falls under a complex and multifaceted area of law (Bassi & Torino, 2019). Despite the efforts of the European Commission to complement this framework with implementation and delegation acts, the enactment of EU 2018/1139 regarding civil aviation, and the initiation of a new mandate for the EU Aviation Safety Agency, several key issues are likely to remain unresolved. These issues, as identified in scholarly discussions, encompass concerns regarding the drone-driven collection and utilization of data, privacy protection, potential breaches of telecommunications and cybersecurity, the registration and identification of drones and operators, and liability and the enforcement of new regulatory provisions (Bassi & Torino, 2019). Overall, the integration of drones into European airspace raises a multitude of legal challenges that extend beyond the scope of the aforementioned framework. Addressing these challenges effectively necessitates ongoing attention and collaboration across various legal domains to ensure the safe and responsible integration of drones into European airspace (Bassi & Torino, 2019).

As has been illustrated, the regulatory framework of drone usage is robust in European countries. Scholarship has also explored the regulatory governance of UASs within European law, identifying three distinct models of governance that have been established to regulate different aspects of the UAS sector (Pagallo & Bassi, 2020). The first model relies upon civil aviation law and EU regulations. It resembles a traditional approach characterized by a combination of top–down regulatory measures and softer, non-binding guidelines. The second model focuses on the application of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (Pagallo & Bassi, 2020). Under this model, a set of legally binding provisions are established, emphasizing the principle of accountability in drone-driven data processing. The third model of governance involves the EU’s use of legal experimentation and coordination mechanisms, aiming to address emerging challenges and uncertainties in UAS regulation through innovative legal methods (Pagallo & Bassi, 2020)

Nevertheless, apart from the insightful contributions described above and from a theoretical standpoint, there seems to be a restricted discussion on how these emerging technologies can align with legal frameworks and evolve in sync with them. There is also a significant dearth of discourse on the appropriate storage and analysis of data collected by drones, all while safeguarding privacy. These aspects are serious deficiencies and form the foundational basis for the research presented in this paper.

Methodology

As previously stated, this paper is aimed at exploring the applications and prospects of UAVs in emergency situations, with a focus on damage assessment and how to protect basic rights in personal data collection. Cases from Taiwan may give us a clear view toward such issues. The Taiwanese cases are then compared with international cases, that is, EU countries with robust regulatory frameworks for the protection of personal data. Several policy suggestions are formulated to help Taiwan and other countries cultivate responsible drone usage, in which personal data are collected in accordance with democratic values. Scholarly research and government documents are reviewed to explore the role of drones in assessing damage during various emergencies, such as hazards and accidents. In addition to the literature review, case studies are discussed to illuminate how UAVs have been used for damage assessment in specific emergency situations and how they can be effectively implemented in damage assessment in Taiwan. Learning from Taiwanese experiences in using UAVs in damage assessment, challenges encountered in drone usage are highlighted and the lessons learned that can inform future deployment, thus enhancing emergency response capabilities and informing future strategies for disaster management. These advantages, in turn, can enable the creation of regulatory settings conducive to drone usage and development.

The significance of this chapter lies in its examination of legal compliance issues when collecting, analyzing, and reusing data collected through drones from the perspective of public policy and with consideration for states of emergency. By reviewing the literature, collecting data from government documents, and examining news reports, this research outlines the enforcement principles that public sector entities utilizing drones for public administration and disaster relief missions should be mindful of. It also helps these entities adapt regulatory systems to new technologies.

Discussion

An Overview of UAV Application in Damage Assessment

How UAVs are used to facilitate the disaster response and damage assessment are discussed in this section. Issues within drone usage such as privacy protection in collecting personal data are discussed to have a more comprehensive view toward the pros and cons of drone usage in response to disasters.

Predominant Application of Multifaceted Types of Drones

Different types of drones are used in emergency response. For example, UAVs are widely used to collect spatial data, such as the scale of flooding or wildfires. These data help government officials decide on where they should first deploy responders (e.g., firefighters). Drones have accordingly elicited the attention of the public sector and relief organizations (Equnox’s Drones, 2023). The high-resolution and low-cost images and data collected by drones helps the public sector provide citizens a sense of size and scale of a given disaster. This also eliminates the need to deploy responders to disaster-affected regions, thereby reducing the risk of harm to humans. Drones assist the public sector in monitoring and controlling disasters, thus advancing the sector’s evaluation of destruction and damage (Majeed et al., 2021). Drone technologies aid the improvement of disaster communication between the public sector and citizens (American Red Cross, 2024). Some drones are sent to disaster-stricken areas for search and rescue operations (for both disaster victims and responders) or the neutralization of elements that may exacerbate disaster effects, such as bombs or toxic chemicals. Drones are likewise used by governments to search for and remove landmines after war. UAVs for on-site fire investigation are employed by fire departments to collect images or evidence that points to the extent of fires and how fire accidents occur. These technologies efficiently deliver emergency supplies to trapped victims or first responders in disaster areas. Moreover, they can extinguish fires and airlift injured victims from affected regions. All these tasks are significant ways by which drones are used to advance disaster response and recovery.

How Drones Carry Out Damage Assessment

Rapid and accurate damage assessment after disasters is critical for recovery works and insurance claims. Traditional damage assessment relies on ground surveys, satellite imagery, and manned aircraft, which may present cost, accessibility, resolution, and safety issues (Sun et al., 2024). Drones contribute to damage assessment by enabling the inspection of perimeters to find as-yet-undiscovered damage (Qanbaryan et al., 2023). Furthermore, drones provide high-resolution imagery from various angles in an accurate and efficient way, helping first responders, engineers, and government officials obtain information sufficient for them to carry out disaster response, rescue, and recovery (Asnafi, 2018). Drones are therefore excellent tools for the immediate acquisition of clear and concrete evidence, which enhances the speed and quality of disaster-related decision-making (Hung, 2024). A specific example is how UAVs are used to analyze landfill capacity and predict filling rate over time through the acquisition of valuable aerial data (Restrepo, 2024).

Legal Pitfalls and Challenges of Drone Usage

The widespread application of commercial, military, and civilian drone technologies has confronted regulatory bodies with significant challenges that span not only technical aspects but also privacy, security, and environmental concerns. Some of the more specific obstacles are those related to flight time and endurance, autonomous flight capabilities, obstacle avoidance technology, communication and remote-control technology, and energy efficiency. These challenges should be addressed through ongoing innovation and research to guarantee the future development of drone technology.

Meanwhile, discussions surrounding the regulation of emerging technologies are integral to modern societies. Although some innovations build upon existing knowledge and can fit within current regulatory frameworks with minor adjustments, others have disruptive characteristics, challenging existing paradigms and necessitating significant regulatory changes or new frameworks altogether. Bridging this gap poses a significant problem. Proponents advocate for enabling regulatory environments to foster research and development, whereas opponents argue for implementing stricter regulations given the uncertainties and potential risks associated with premature technologies. This debate may lead to a stalemate, further delaying the adaptation of regulatory systems to new technologies.

Of particular concern are issues pertaining to privacy and data protection, which arise from the utilization of cameras, sensors, and other peripherals commonly integrated into small UAVs. For example, when drones are used to collect image data of a disaster area, how to assure the photos taken from private properties in the disaster area will be protected or responsible used in damage assessment or disaster response has become a critical question nowadays. Besides, the possible cyberattacks against drones have become another security and privacy threats (Mekdad et al. 2023). Rather than establishing regulations focusing solely on UAVs themselves, a distinct regulatory approach should be extended to sensors and peripherals, which hold significant relevance to human daily life. The inherent imbalance in the treatment of various potential risks and concerns in UAS regulations arises from the constrained purview of regulatory and administrative bodies tasked with formulating, implementing, and enforcing rules governing UAS design, manufacture, and operation. Currently, the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) of Taiwan serves as the primary regulatory and administrative overseer of the regulatory landscape. However, its traditional mandate pertains to the safety of airplane operations and civil aviation, thereby limiting its capacity to comprehensively address all relevant concerns associated with UASs (Du & Heldeweg, 2017). This problem has given rise to the following question: How can UAS regulations be refined to effectively address the multifaceted social implications of drone usage that include, but are not limited to, privacy, data protection, and security concerns?

Fostering the Responsible Development of Novel Technologies

The increasing usage of UAVs has raised significant privacy concerns, requiring a balanced approach to regulation and innovation. Improving drone efficiency in damage assessment is crucial, especially in the wake of hazards where rapid and accurate evaluations can save lives and resources. Taiwan serves as a compelling case study to explore the applications and pitfalls of UAVs in emergency situations, highlighting both the potential benefits and the complexities involved in integrating these technologies into damage response frameworks.

Privacy Issues Confronting Drone Usage

As drone technology develops, governments struggle to regulate the activities of operators, manufacturers, and stakeholders given the challenge of adopting new laws related to UAV usage (Agapiou, 2021). For example, regulations prohibit a drone operator from entering sensitive areas, such as airfields (Majeed et al., 2021), but such prohibition is insufficient to prevent the leakage of private data from people who are unwilling to share images of their property. The lack of robust regulations or standard operating procedures may reduce the legitimacy of drone usage for disaster response. Robust frameworks for preventing possible human rights violations in the use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) to collect data from citizens have been established by European countries. Examples include the Digital Services Act and the Digital Markets Act, which are intended to protect citizens’ privacy in EU countries. The problem is that regulations exclusively dedicated to drone usage are lacking. A robust system for regulating drone use should be created by the public sector to oversee aspects such as occasions that warrant UAV implementation and the qualifications of drone operators. To reduce possible abuse of power in collecting personal property information through drones (e.g., using UAVs to take photos), legislators may borrow ideas from laws on privacy protection or personal information collection. Regulations for drone operation, data gathering, and data usage are critical for human rights protection. Ethical issues are as important as basic rights protection in drone use (Restrepo, 2024).

Improving Drone Efficiency in Damage Assessment

Drones help enhance damage assessment by capturing high-quality images and videos, mapping large and complex areas, integrating with AI and cloud computing, reducing costs and risks, and improving communication and coordination (LinkedIn, 2024). Nevertheless, possible low reliability and considerable operational costs reduce the public sector’s willingness to use drones compared with its willingness to send human beings to disaster areas. Furthermore, the tradeoff between the need to scan a large expanse of a disaster-affected region and ensuring rapid response time for information transmission may have critical effects on the efficiency of drone usage in damage assessment. Scholars suggested that en-route data transmission instead of data transmission at the end of routes enhances the operating efficiency of drones (Yucesoy et al., 2023). AI and machine learning techniques have also served as efficient methods for improving the operation of drones in decision-making (Restrepo, 2024). The rapid development of ICTs, such as machine-to-machine communication and high-speed data transmission (e.g., 5G internet), enable the autonomous and easy operation of drones, even in harsh environments, such as hazard zones (Restrepo, 2024).

Applications and Prospects of UAVs in Emergency Situations: Taiwan as a Case Study

Using drones in emergency assessment has become popular in global cities. In Taiwan, for example, drones have been widely used for different purposes, such as the survey of forested land and the security inspection of bridges and elevated roadway structures. A more specific example is the LUF-60 Firefighting Robot purchased by the Taipei City Fire Department in 2023 to enhance firefighting efficiency and securing the lives of firefighters (Wu, 2023). This robot has the following main functions: chemical foaming, water mist cooling, smoke-exhaust systems, and water injection to combat fires. It can be manipulated by remote control when navigating narrow streets or lanes where fire accidents occur.

Another example is the first police drone team created in New Taipei City in July 2021. The drone team deals with administrative enforcement, investigates crime scenes in complex terrains, and monitors traffic conditions in the city. The city government believes that the drone team improves the efficiency of case handling, assists in the execution of disaster relief tasks, and enhances security in citizens’ daily lives (New Taipei City Government, 2021).

UAVs have likewise become increasingly popular devices for recreational or commercial use in Taiwan. Many UAV owners use their devices to take photos in popular tourist spots, but some fly into airports and pose tremendous threats to flight security. In March 2023, an unauthorized UAV was spotted near the runway of Taiwan Taoyuan Airport, which had to be temporarily closed for 40 minutes and reopened only after the drone was removed. The flights of about 1,000 passengers were delayed due to this incident, and the drone owner faced a potential fine of NT$300,000 (about US$9,500) to NT$1.5 million for violating the Civil Aviation Act (Everington, 2023). As previously stated, laws such as the Civil Aviation Act can be used to regulate UAVs, but a comprehensive or fundamental law that regulates drone use is lacking. Only two laws currently deal with drone usage: the Civil Aviation Act (for UAVs) and the Standards Governing Prevention of Industrial Robots Hazards (SGPIRH). The SGPIRH covers industrial robots for occupational use only. Thus, competent authority of drone affairs and regulation in Taiwan remain insufficient. In 2020, 51 public service agencies in Taiwan used 187 drones made by Chinese corporations, such as DJI, the world’s leading brand in drone technology development (Yang & Huang, 2022). However, despite China’s evolution as a leader in the drone industry, the Taiwanese government has prohibited the use of Chinese ICTs products owing to national security issues. Notably, the Taiwanese central government banned Chinese manufacturers from being included as options for government purchases and established a research and design site in southern Taiwan in 2022. It has spent nearly NT$800 million on the purchase of UAV hardware, software, and services. Nonetheless, the inconsistent quality in these innovations has constrained the efficiency of using “Made in Taiwan” (MIT) drones for disaster response. According to a senior official in Taiwan’s national fire administration, MIT drones purchased by the central government “are only good [for display]; no one dares fly them” (Yang & Huang, 2022).

As mentioned earlier, China leads the drone industry, especially in terms of UAV development, and many international users purchase Chinese-manufactured drones for personal, commercial, or government use. However, some drones made in China (MIC) may have serious security issues that allow the transmission of data to manufacturers’ servers in China. The FBI has warned the public that the widespread use of MIC drones in critical infrastructures in the US is a potential threat to national security. Using Chinese-manufactured drones also runs the risk of leaking critical infrastructural data to the Chinese government and putting key networks at risk of cyberattacks (Willemyns, 2024). Similar to Taiwan, the US has banned the federal government and its agencies from procuring or using drones manufactured by Chinese firms. The US’s well-functioning supply chain and sophisticated ICT industry are excellent prerequisites to developing a vibrant drone industry in the country, which enhances national competitiveness in today’s digital era. With the increasing use of drones in response and recovery the advent of more drone-related requirements is expected to pave the way for the drone industry to lead the international market. Yet, another challenge arising in this regard is the fact that many American-made drones are inferior and more expensive than their MIC equivalents (Willemyns, 2024).

The Civil Aviation Law in Taiwan is underlain by a case-by-case regulatory model, leaving room for optimization and adjustment. Given the characteristics of the drone regulations mentioned above, Taiwan amended provisions related to drones in the Civil Aviation Law in 2018. This version focuses on overseeing drones larger than those falling under the microcategory, with limited flight altitudes, endurance levels, radii, and speeds allowed and drones to be operated within the visual line of sight of an operator. Exceptions to these rules are the drones designed and manufactured (or imported) for specific purposes by government agencies, schools, or individuals operating in the legal domain or those used by government agencies in the performance of statutory duties. Perhaps there is some reasonable basis for this approach (including considering local conditions and industry opinions). Nonetheless, many aspects of the Civil Aviation Law’s regulation of remotely piloted drones can still be optimized and adjusted.

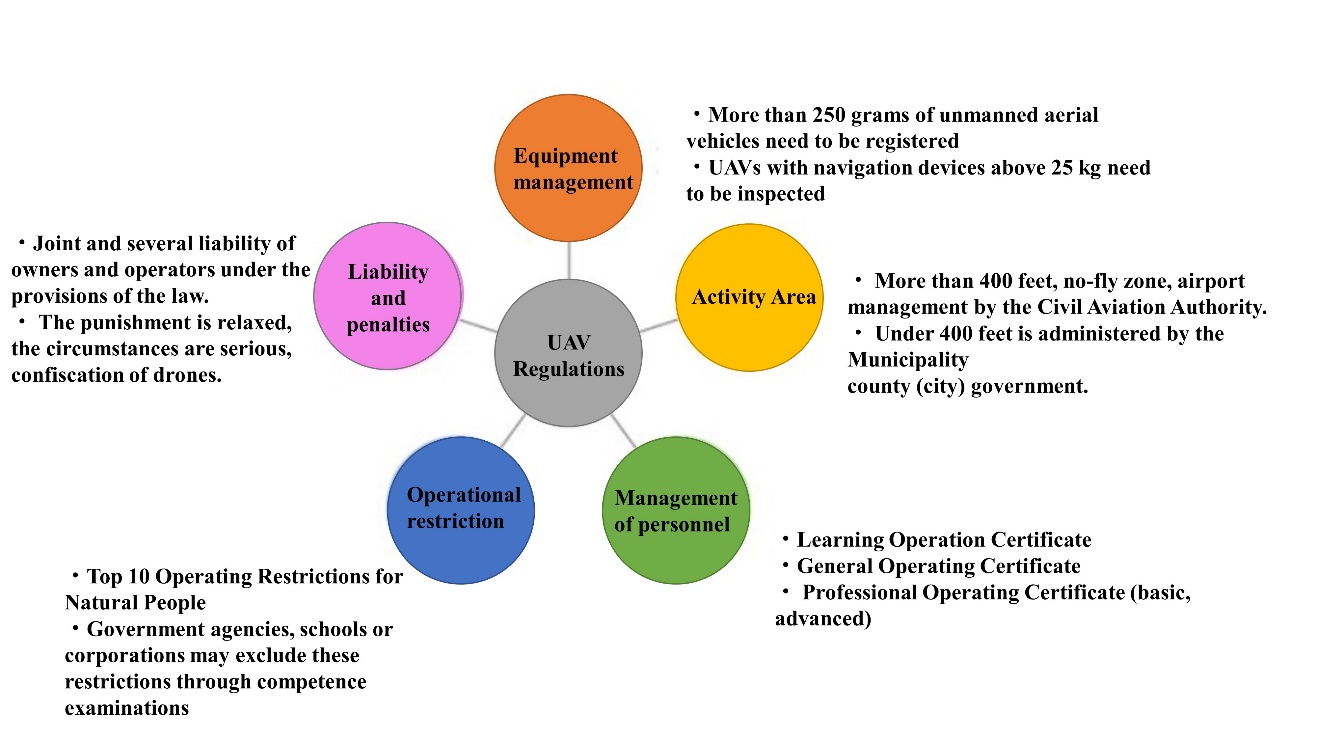

In response to the increasing prevalence of remote-controlled drone activities, the Ministry of Transportation and the Civil Aviation Authority of Taiwan have drawn upon legislative experiences from regions such as the United States, the EU, and Japan, as well as regulations from the International Civil Aviation Organization. After considering domestic circumstances and stakeholders’ opinions, these bodies have integrated principles of public safety, social order, aviation safety, and industrial development into the Civil Aviation Act (Wu, 2020). The latest version, which was enacted on March 31, 2020, includes a chapter on remote-controlled drones and relevant authorizing regulations (Wu, 2020). The key points covered include equipment management, activity areas, personnel management, operational restrictions, liability, and penalties (Diagram 1) (Wu, 2020).

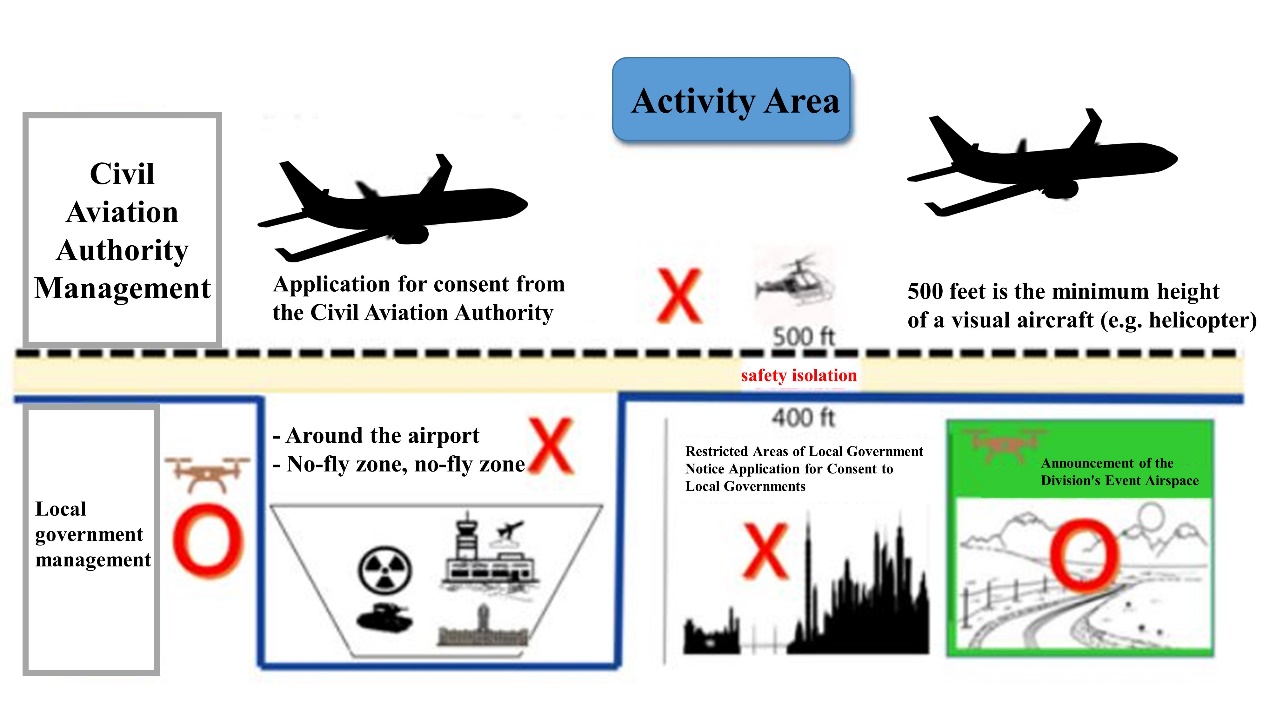

Engaging in aerial activities using remote-controlled drones is subject to regulations, which divide permissible activity areas into centrally managed areas overseen by Taiwan’s CAA and locally managed areas (Diagram 2). In centrally managed areas, the CAA establishes restricted zones within a certain distance around no-fly zones, restricted zones, aerodromes, and airports on the basis of aviation or national security requirements. Local governments (including municipalities directly governed by central authorities and county/city governments) announce areas, times, and other management measures for prohibiting or restricting remote-controlled drone activities according to public welfare and social security purposes (Wu, 2020). In areas under the supervision of local government authorities, if bodies such as the Ministry of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Justice, or Ministry of National Defense deem it necessary to prohibit or restrict drone flight activities, they may request inclusion in announcements made by municipal or county/city governments (Diagram 2) (Wu, 2020).

Establishing a Feasible Regulatory Framework for UAV Use: Policy and Legal Implications

Establishing a regulatory framework for UAV use requires addressing policy and legal issues to ensure sustainable development, public safety, and social accountability. This involves national-level centralized authority to coordinate implementation strategies for cohesive oversight, followed by identifying appropriate authorities and delineating responsibilities for personal data breaches disputes. Adopting a dual-track approach to regulating accident liability for autonomous drones will balance innovation with accountability, fostering a sustainable and responsible drone ecosystem.

Requiring National-Level Development Prospects and a Competent Centralized Authority to Formulate and Coordinate Implementation Strategies

Drone technology, infrastructure, and standards are continually evolving. Considering Taiwan’s insular situation in the international and cross-strait context, drone innovation should be considered a strategically important industry by the nation. Inter-agency cooperation surrounding drone operations is crucial for maximizing the benefits and synergies across various sectors. Ministries such as Transportation, Economics, Defense, Interior, Digital Development, and Education, along with government agencies like the National Development Council, National Science Council, Council of Agriculture, Public Construction Commission, National Communications Commission, and Financial Supervisory Commission, should collaboratively formulate and execute implementation plans.

Coordinated efforts ensure that each entity leverages drones for its specific needs while contributing to a cohesive national strategy. For example, the Transportation Ministry can utilize drones for infrastructure inspection and traffic management, while the Defense Ministry focuses on security and emergency response. The Council of Agriculture can use drones for crop monitoring and pest control, enhancing agricultural productivity. The National Communications Commission can regulate and standardize drone communication protocols to ensure safety and efficiency.

Joint planning and budget allocation enable resource optimization and prevent redundancy. It fosters innovation through shared knowledge and technology transfer. Moreover, a unified approach enhances regulatory compliance and public safety, promoting confidence in drone applications. Alternatively, the National Development Fund can guide and financially support the development of domestic drone manufacturers into unicorns, effectively promoting the industry of drone usage for military and commercial purposes. To effectively execute overarching plans and assess performance, the Executive Yuan, led by the vice premier or political deputy ministers, should coordinate interministerial cooperation and designate departments that will establish execution centers or promotion offices at both central and local levels (CTIC, 2023).

Identifying Competent Authorities and Allocating Responsibilities When Personal Data Infringement Occurs

The collection of data using UAVs has not been formally incorporated into current civil aviation laws in Taiwan, as discussed in the second regulatory model. Similarly, the EU addresses the collection of personal data by UAVs through the GDPR. In theory, therefore, one must revert to Taiwan’s Personal Data Protection Act to determine the regulatory framework based on whether a data collection entity is a government agency or a non-government entity, each subject to different regulatory stipulations.

Government agencies are subject to the stipulations of Article 15, while non-government entities are subject to the provisions of Article 19. According to Chapter II Data Collection, Processing, and Use by a Government Agency, Article 15 regulates the legitimate and lawful collection of personal data by government agencies, which demonstrates that except for the personal data specified under Paragraph 1 of Article 6, the collection or processing of personal data by government agencies shall be for specific purposes and based on one of the following grounds:

- Where it is necessary to perform its statutory duties within the necessary scope;

- Where consent has been obtained from a data subject;

- Where the rights and interests of the data subject will not be infringed upon.

Article 16 stipulates that except for the personal data specified under Paragraph 1 of Article 6, government agencies shall use personal data only within the necessary scope of their statutory duties and for the specific purpose of collection. The use of personal data for other purposes shall be based on any of the following grounds: 1) where it is expressly required by law, and 2) where it is necessary for ensuring national security or furthering public interests. The government may apply Article 16, Paragraph 2, involving national security or public interests, to justify the use of personal data for purposes other than those originally intended. However, this may also pose a risk of abusive administrative discretion, demonstrating the insufficiency of current legislation and liability regulations.

Non-government agencies are required to comply with Article 16, which states that the collection or processing of personal data by non-government agencies shall be for specific purposes and warranted by one of the following bases:

- where it is expressly required by law;

- where there is a contractual or quasi-contractual relationship between a non-government agency and a data subject, and appropriate security measures have been adopted to ensure the security of the personal data;

- where personal data have been publicized legally or manifestly made public by the data subject;

- where it is necessary for statistics gathering or academic research by an academic institution in pursuit of public interests, provided that such data, as processed by the data provider or as disclosed by the data collector, may not lead to the identification of a specific data subject.

Until more comprehensive regulations are enacted under the current Civil Aviation Act, jurisdiction over incidents involving personal data breaches or infringement of information privacy through UAVs remains ambiguous, that is, whether dedicated supervisory authorities, including the National Development Council, the Civil Aeronautics Administration under the Ministry of Transportation, or even the Ministry of Digital Development, are responsible for drone-related regulation.

Due to the inclusion of both government agencies and non-government entities as future subjects of personal data regulation, the scope of regulation is extensive, and the number of entities involved is significant. Moreover, as the collection, processing, and utilization of personal data are inherent in various types of duties, a necessary task is to design a feasible regulatory framework that ensures the effective execution of responsibilities and competent data governance. In situations where conflicts may arise in the responsibilities of other enforcement agencies (e.g., the Civil Aviation Act), an important requirement is to establish personal data regulation authorities that coordinate and cooperate with such agencies to delineate responsibilities and guarantee the effective allocation of government regulatory responsibilities.

Studies have indicated that, for special purposes or statutory duties involving government agencies, schools, or private institutions, only a passive relaxation of restrictions is adopted, which translates to excessive discretion in approval authority. Relying on case-by-case approvals to establish operational regulations for drones with special types and functions may create a barrier to entry given regulatory ambiguity, which is detrimental to the long-term development of the drone industry. The types and functions of drones subject to regulation should be expanded, and these technologies should be regulated separately and explicitly (CTIC, 2023).

Adopting a Dual-Track Approach to Regulating Accident Liability Involving Autonomous Drones

Autonomous drones have long been extensively used and refined for general civilian aircraft, and autonomous drones controlled by artificial intelligence will soon emerge. Currently, however, there is no consensus on the regulation of accident liability involving autonomous drones. This indicates that the absolute liability imposed by the Civil Aviation Act on all drone owners is insufficient to address the complex dimensions of liability and attribution. A recommendation is to adopt a dual-track regulatory approach, in which autonomous drone developers are required to impose absolute limitations on the range of autonomous decision-making, with ultimate control delegated to humans in terms of design, manufacture, and use, to ensure accountability. Unavoidable accidents caused by machine learning technologies should be attributed to the programmers of autonomous drone software, compelling them to bear the risks arising from the autonomous actions of drones (CTIC, 2023).

Conclusion

UAVs present a transformative opportunity for enhancing emergency response capabilities across multiple sectors in Taiwan. Creating a regulatory framework with explicit guidelines addressing institutionalized application for various drones is imperative. This approach fosters innovation while ensuring compliance, mitigating regulatory ambiguity, and supporting the sustainable growth of the drone industry by providing clear, consistent, and fair regulations. By adopting these measures, Taiwan can realize the potential of UAVs, enhancing its capacity to emergency response and mitigation effectively. This plan must intricately weave the resources and expertise of various ministries and government agencies, including transportation, economics, defense, interior, digital development, and education ministries. Through the collaborative efforts and strategic allocation of budgets, synergies can be maximized, paving the way for the holistic growth of the drone industry.

Effective regulation is another cornerstone of sustainable industry development. Legislation governing drone use impacts various critical areas, including effectiveness, human rights, public safety, and national security. An integrated and cross-departmental strategic vision and regulatory intensity are required to balance and reconcile multiple interests such as innovation efficiency, privacy, and public trust, necessitating careful consideration and deliberation. Taiwan requires establishing precise and unambiguous legislation on the types and functions of drones, as well as a liability framework for autonomous drones. Ambiguity in regulations can stifle innovation and hinder industry progress. Therefore, adopting a dual-track regulatory approach, with shared accountability between programmers and operators, can mitigate risks and ensure the responsible deployment of this technology.

The regulation of data collection via UAVs remains a complex and evolving issue, both internationally and domestically. While current civil aviation regulations and guidelines in Taiwan lack specific provisions addressing UAV data collection, similar to the EU’s approach through the GDPR, oversight falls on Taiwan’s Personal Data Protection Act. This act distinguishes between government and non-government entities, subjecting each to different regulatory frameworks. In essence, addressing the regulatory gaps and ambiguities surrounding UAV data collection requires a nuanced approach that balances technological innovation with privacy protection and administrative oversight. Clear guidelines/standards and robust oversight mechanisms are essential to ensure responsible and ethical data practices in the rapidly evolving landscape of UAV technology. This case study highlighted the reliance on regulatory and policy frameworks, as well as the crucial influence of inter-agency coordination, for the development and application of drones in emergency response.

References

American Red Cross. 2024. “Benefits and Costs of Drone Use for Disaster Response.

American Red Cross.” American Red Cross : https://americanredcross.github.io/rcrc-drones/benefits-costs.html.

Australia government. 2024. “Disaster Relief Using Drones.” Drones.gov.au: https://www.drones.gov.au/drones-australia/how-are-drones-being-used-australia/disaster-relief.

Bassi, E. 2019. “European Drones Regulation: Today’s Legal Challenges. In 2019 international conference on unmanned aircraft systems (ICUAS) (pp. 443-450). IEEE.

Clark, D. G., Ford, J. D., and Tabish, T. 2018. “What Role Can Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Play in Emergency Response in the Arctic: A case Study from Canada.” PLoS ONE 13(12), e0205299. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205299.

CTCI Foundation. 2023. “The Challenges of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Technology and Industry Development in Taiwan. CTCI Foundation: https://www.ctci.org.tw/8838/research/26382/44825/.

Equnox’s drones. 2023. “Promoting Effective Disaster Management Through Drones.” Equnox’s drones: https://www.equinoxsdrones.com/promoting-effective-disaster-management-through-drones/.

Everington, K., 2023. “Unidentified Flying Object Forces Closure of Taiwan Taoyuan Airport.” Taiwan News: https://www.taiwannews.com.tw/en/news/4898605.

Fosch-Villaronga, E., and Heldeweg, M. 2018. “Regulation, I presume?” Said the Robot–Towards an Iterative Regulatory Process for Robot Governance.” Computer law and security review 34(6), pp. 1258-1277.

Glantz, E. J., Ritter, F. E., Gilbreath, D., Stager, S. J., Anton, A., and Emani, R. 2020. “UAV Use in Disaster Management.” Paper presented at the 17th ISCRAM Conference. Blacksburg, VA.

Hilson, G. 2024. “The Expanding Roles of Emergency Drones for Disaster Management.” Verizon: https://www.verizon.com/business/resources/articles/s/the-role-of-emergency-drones-in-disaster-management/.

Hung, D. V., 2024. “Drones for Assessment of Disaster Damage and Impact – Revolutionizing Disaster Response.” UNDP: https://www.undp.org/vietnam/blog/drones-assessment-disaster-damage-and-impact-revolutionizing-disaster-response Outline.

Kyrkou, C., & Theocharides, T. 2019. “Deep-Learning-Based Aerial Image Classification for Emergency Response Applications Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles.” In CVPR workshops (pp. 517-525).

Majeed, R., Abdullah, N.A., Mushtaq, M.F., and Kazmi, R. 2021. “Drone Security: Issues and Challenges.” International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications 12(5), pp. 720-729.

Mekdad, Y., Aris, A., Babun, L., El Fergougui, A., Conti, M., Lazzeretti, R., and Uluagac, A. S. 2023. “A Survey on Security and Privacy Issues of UAVs.” Computer Networks 224: 109626.

Mohsan, S. A. H., Othman, N. Q. H., Li, Y., Alsharif, M. H., & Khan, M. A. 2023. “Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): Practical Aspects, Applications, Open Challenges, Security Issues, and Future Trends.” Intelligent Service Robotics 16, pp. 109-137.

New Taipei City Government. 2021. “Safe and Secure: Taiwan’s First Police Drone Team.” New Taipei City Government: https://sdgs.ntpc.gov.tw/en/home.jsp?id=3d145d2a095e211d&act=be4f48068b2b0031&dataserno=6ff571c5aa19eb16f5ea80f837ca5e3b.

Pagallo, U., and Bassi, E. 2020. “The Governance of Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS): Aviation Law, Human Rights, and the Free Movement of Data in the EU.” Minds and machines 30(3), pp. 439-455.

Rabta, B., Wankmüller, C., and Reiner, G. 2018. “A Drone Fleet Model for Last-Mile Distribution in Disaster Relief Operations.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 28, pp. 107-112.

Restrepo, A. 2024. “Impact of Drone Technology on Security: Perspectives and Challenges.” Ventas de Seguridad: https://www.ventasdeseguridad.com/en/2024011223877/articles/technological-analysis/impact-of-drone-technology-on-security-perspectives-and-challenges.html.

Samad, T., Bay, J. S., and Godbole, D. 2007. “Network-Centric Systems for Military Operations in Urban Terrain: The Role of UAVs.” in Proceedings of the IEEE 95(1), pp. 92-107, doi: 10.1109/JPROC.2006.887327.

Shamsoshoara, A., Afghah, F., Razi, A., Mousavi, S., Ashdown, J., and Turk, K., 2020. “An Autonomous Spectrum Management Scheme for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Networks in Disaster Relief Operations” in IEEE Access 8, pp. 58064-58079, doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2982932.

Sun, J., Yuan, G., Song, L., and Zhang, H. 2024. “Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in Landslide Investigation and Monitoring: A Review.” Drones 8(1), https://doi.org/10.3390/drones8010030.

Willemyns, A. 2024. “Chinese Drones may Pose Security Risks, US Agencies Warn.” Radio Free Asia: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/china/drone-dji-ban-01182024113315.html.

Wu, T. 2023. “Taipei City Fire Department Introduces Multi-functional Firefighting Robots to Improve Disaster Relief Efficiency.” Taiwan Immigrants’ News Network: https://news.immigration.gov.tw/NewsSection/Detail/C16DEC05-444A-477E-88DD-7125B1DD4061?lang=TW.

Wu, J. Y., 2020. “Preliminary Exploration of UAV Regulations by the Civil Aviation Administration.” Industrial Technology Research Institute Industry Learning Network: https://college.itri.org.tw/Home/InfoData/f6e19f2d-f81c-421c-bc36-ea6409ba0a5d/92b710cc-38d3-4c6f-a63f-363a3fe40f43?fbclid=IwAR0LgjeJqcEpdrY2H20akSDs8_StFd7PktUU_-HCCJrJHY29T-vYdisHUKs.

Yang, M. H., and Huang, E., 2022. “In Taiwan, A National Drone Fleet Rises from the Ruins.” Commonwealth Magazine 757, https://english.cw.com.tw/article/article.action?id=3302.

Zhang, C., Li, X., He, C., Li X., and Lin, D. 2023. “Trajectory Optimization for UAV-Enabled Relaying with Reinforcement Learning.” Digital Communications and Networks https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcan.2023.07.006.

Zhang, Z., and Zhu, L. 2023. “A Review on Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Remote Sensing: Platforms, Sensors, Data Processing Methods, and Applications.” Drones 7(6): https://doi.org/10.3390/drones7060398.