3 Behaviourally-Informed Early Warning and Anticipatory Action: Unleashing the Potential of Locally-Led Pre-emptive Response and the Forecast-Based Financing it Requires

Josh Ayers; Oenone Chadburn, MA (Econ); and Kazi Amdadul Hoque, MA, MPH, MSS

Authors

Josh Ayers, Resilience Innovation Group, LLC

Oenone Chadburn, International Aid Consultant

Kazi Amdadul Hoque, Start Ready; Friendship NGO

Keywords

anticipatory action, early warning, people-centred, forecast-based financing, preparedness, localisation

Abstract

The ultimate goal of early warning systems is to elicit preparedness and early actions to mitigate the impact of an impending hazard. This chapter discusses the relatively new approach to humanitarian response called Anticipatory Action (AA) and its reliance on well-developed, trustworthy, and people-centred early warning systems (PC-EWSs). Anticipatory action or forecast-based action models represent an innovative leap forward in facilitation of more inclusive effective early preparedness, prevention, and mitigation actions from the exposed and vulnerable populations themselves. This study leverages existing literature on the effectiveness of PC-EWSs to examine one of the leading anticipatory action efforts globally – the Start Network and Start Fund – in an effort to identify the ways in which PC-EWSs are utilised and strengthened to inform anticipatory early action. The research identified four main factors that condition that effectiveness and utilisation: (1) participation of end users in PC-EWS development and administration to enhance trust in warnings, (2) localization and contextualization of PC-EWS function and messaging, (3) orientation of PC-EWSs toward promotion and facilitation of action, and (4) vertical linkages of local relief actors to donors and international stakeholders at higher scales. Finally, this chapter concludes with the findings of the study on the Start Network and Fund that both corroborate the importance of these factors and identify new challenges and further research needs associated with making anticipatory action a more mainstream humanitarian practice.

Introduction

EWS are only as good as the actions they catalyse; action is an essential part of any warning system. If a warning is sounded, and no one takes the action that the warning was intended to trigger, then the warning system failed. (IFRC 2012)

Early Warning Systems (EWSs) operate on the fundamental premise that information related to potential hazards can be collected, analysed, transformed into warning messages, and distributed with sufficient lead time to alert at-risk populations about impending disasters. The ultimate goal is to elicit preparedness and early actions that can avert or alleviate the impact of the disaster.

Over time, our knowledge of the socio-economic and political dimensions of risk has advanced, significantly improving the quality and promptness of warning information. Despite this positive trend, an examination of existing literature reveals that EWSs have predominantly been crafted by technocrats, with a focus on informing governments and official stakeholders of the technical details of the hazard (severity, location, etc.) and when emergency operations should commence. These systems are intricate, requiring collaboration across various domains such as science, technology, government, news media, and the public (Sorensen 2000). While strides have been made in making EWSs more people-centric in the formulation of warnings, there remains a notable gap in understanding how to effectively facilitate early preparedness, prevention, and mitigation actions from the exposed and vulnerable populations themselves. The challenge lies in bridging this divide to ensure a more comprehensive and inclusive approach to building resilience and managing disasters. Anticipatory action or forecast-based action models represent an innovative leap forward in this effort for the international humanitarian aid and emergency management community.

Anticipatory Action (AA) is defined as acting ahead of predicted hazardous events to prevent or reduce acute humanitarian impacts before they fully unfold (Knox-Clarke 2022). The relationship that people-centred early warning systems (PC-EWSs) have to AA, and the financing which supports them, is a relatively unexplored area of knowledge. Specifically, more work is needed in the piloting, evidence of impact, and capability of programming at scale. Nonetheless, applying the cost effectiveness[1] of AA to household-level behaviour is a worthy goal for emergency management and humanitarian practitioners.

A significant number of humanitarian actors, such as the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), the World Food Programme (WFP) and the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), have recognised the value of AA. They have developed multilateral coordination mechanisms for AA to promote innovation, technology, and information exchange, as well as support for learning, skills development and nurturing partnership. However, these mechanisms are vulnerable to accidentally reinforce technocratic approaches. They support AA for high impact, wide-reaching disasters with intensive risk exposure. In addition, according to the Global Network for Civil Society Organisations for Disaster Reduction (GNDR), these often fail to leverage people-led approaches required for extensive risk exposure of the “everyday disasters” that the most vulnerable populations frequently face (GNDR 2021).

This chapter, taken from the view of practitioners, will explore whether effective PC-EWSs (utilising the Sendai Definition of EWS – see Text Box A) can be supported and mutually reinforced by localising decision making for the timely release of anticipatory finance, and the subsequent locally led delivery of AA programmes.

TEXTBOX 1: Early Warning System – Sendai Definition

Anticipatory Action Efforts by Start Network

In a world where demand for humanitarian aid is exponentially driven by climate change impacts and conflict over dwindling natural resources, Start Network[2]’s fundamental premise is that the humanitarian system is reactive, fragmented, and inefficient, and therefore currently not fit for purpose.

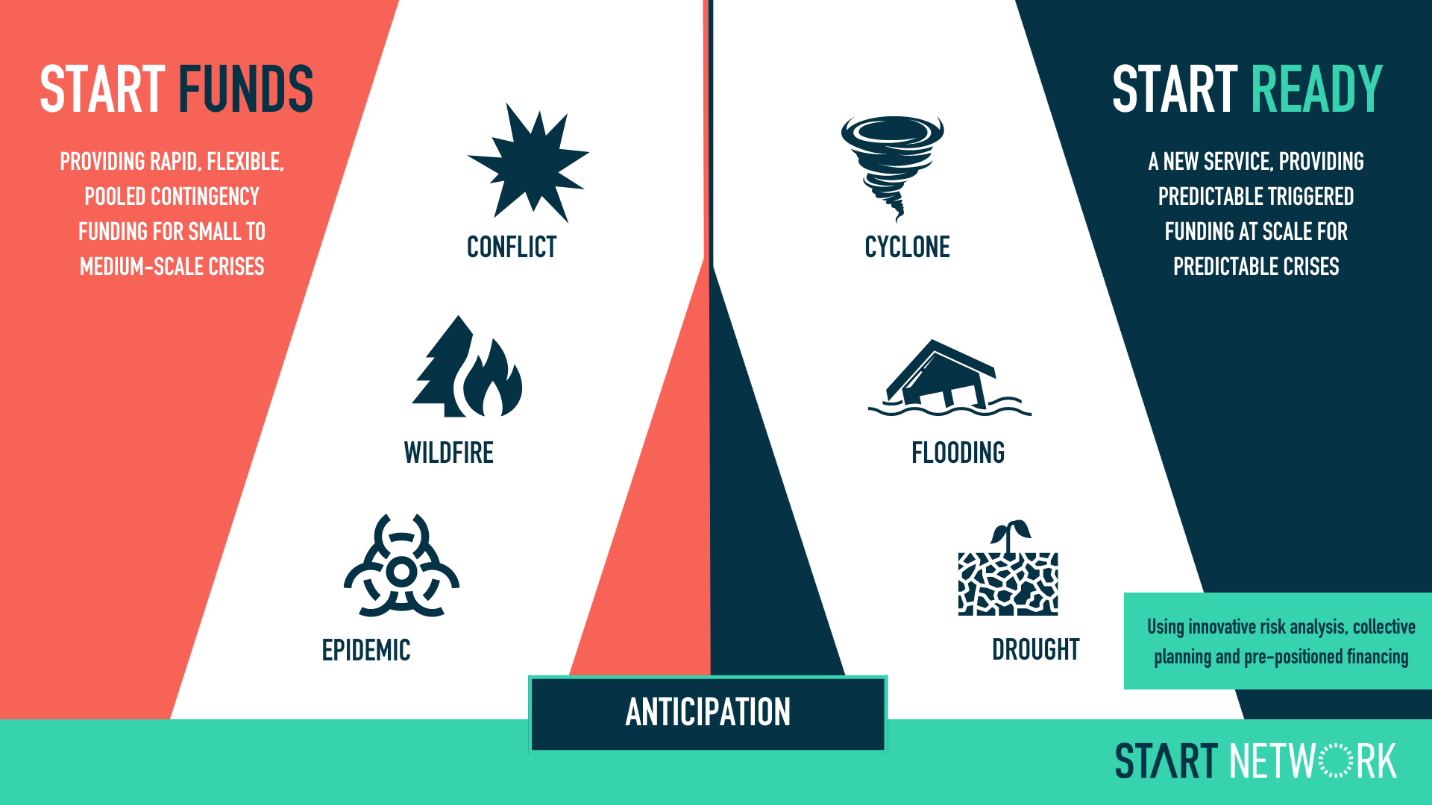

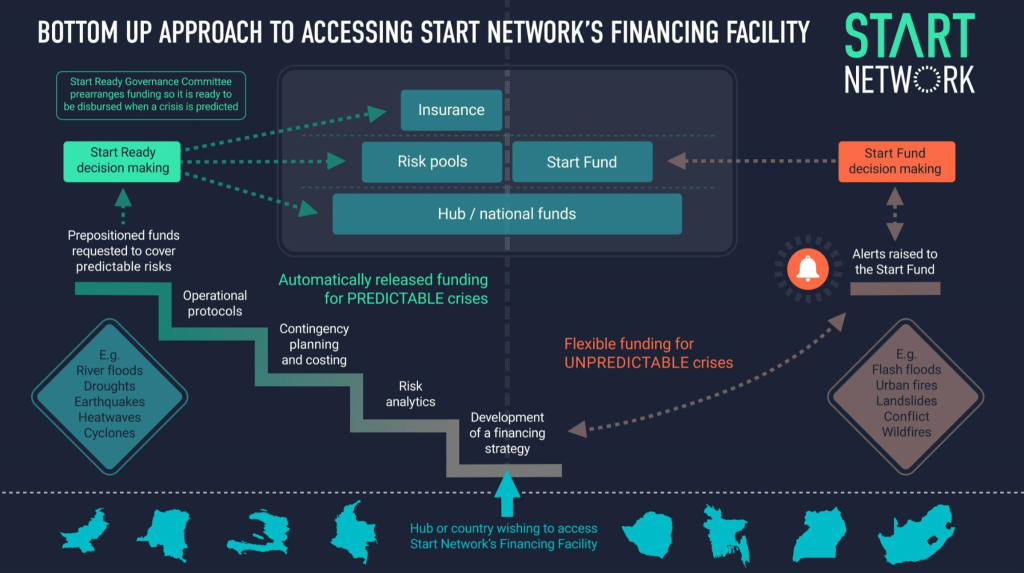

The goal of the Start Network is a timelier, cost-effective set of mechanisms and entities which are locally led, providing contextual insight and community reach to reduce risks, especially on predictable disasters. Since its launch in 2012, the financial instruments which Start Network has evolved are designed experientially to demonstrate new pathways for change (See Figure 1). Led by practitioners, the Start Fund (launched in 2014) and Start Ready (launched in 2021) have been piloting locally led solutions which have replicable global reach, with an aim to present viable alternatives to traditional funding mechanisms. Start Network’s aim is to provide evidence to these approaches, evolving the humanitarian ecosystem away from needs based centralised responses, which launch after significant loss and damage has occurred, towards predictable financing for locally designed solutions, which protect people and assets from loss and harm.

Designing programmes to ensure positive early action behaviours has not always been front and centre of Start Network approaches. Design has often centred around alternative mechanisms, processes, and structures which an international aid practitioner would understand. The softer side of community behaviour change, empowering households with disaster risk knowledge to determine positive behaviours for early action is only just starting to emerge as a priority. Learning from the country level has shown that it is not just the advanced collaborative plans that will support locally led AA. The process of planning itself needs to enhance trust, and support contextualisation and local ownership of early action actions.

This chapter will take Start Ready as a case study for AA in order to better understand its relationship to PC-EWSs. It will utilise a spatial level approach to explore the design of Start Ready at the local, national, and international levels, describing the interaction of these levels to reinforce a bottom-up approach to collaboration and scalability, and hence the people-centred nature of the global mechanism. It will review how steps to design a locally led disaster risk financing system has led to new insights for humanitarian actors, how communities have designed their own contingency plans, and how ownership and trust develops within communities when they contribute to the development of the triggers used to release funding for AA. The chapter will explore how the confidence in the existence and delivery of these anticipatory funds supports the efficacy and reliability of PC-EWSs which, in turn, allow people to make more informed choices to protect their lives, communities and assets.

Literature Review

To help situate the exploratory discussion of practical applications of anticipatory funding and action informed by early warnings, a comprehensive literature review was performed on the evolution of early warning systems (EWSs) and their application to preparedness and early action against impending disasters.

Over the past thirty years or so, social constructivist understandings of risk and vulnerability have emerged (see, for example, Mileti 1995; Tierney 2014; or Krüger et al. 2015) to enrich the ways in which we interpret and engage with natural hazards and disaster events, including EWSs, preparedness, and early action. This arguably more human approach to disaster management has given rise to more “people-centred” approaches to EWSs development, administration, preparedness, and resilience building (Schilderinck 2009; Nyakeyo 2016). The new approach is illustrated clearly in 2006 by the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) and the German Federal Foreign Office’s Platform for the Promotion of Early Warning (PPEW), which described the objective of people-centred early warning systems (PC-EWSs) as the “empowerment of individuals and communities threatened by hazards to act in sufficient time and in an appropriate manner to reduce the possibility of personal injury, loss of life and damage to property and the environment.” (Wiltshire 2006, 2). To achieve this objective, the PPEW suggested several critical elements of PC-EWSs, including enhancing the ability of affected populations to respond to emergencies through risk education, participation, and preparedness activities (Wiltshire 2006).

The examined literature suggests that transitioning from a technological emphasis to a people-centric strategy has proven beneficial in enhancing the effectiveness of EWSs by encouraging and facilitating early action from end users (Ahsan et al. 2016; Arlikatti et al. 2018; Bronfman et al. 2016; Cordasco et al. 2007; Donovan et al. 2018; Fakhruddin et al. 2015; Haynes et al. 2008; Paton 2008; and Paton et al. 2010). In a notable shift toward embracing early action as the end goal of early warning for early action, UNDRR defined early warning system as, “an integrated system of hazard monitoring, forecasting and prediction, disaster risk assessment, communication and preparedness activities, systems, and processes [emphasis added] that enable individuals, communities, governments, businesses and others to take timely action [emphasis added] to reduce disaster risks in advance of hazardous events.” (n.d.).

It is well established that when a high level of trust exists between those who generate information and vulnerable populations, the likelihood of the latter utilising the provided information to prepare for hazards increases (Cordasco et al. 2007; Haynes et al. 2008; Paton 2008; Paton et al. 2010; Fakhruddin et al. 2015; Bronfman et al. 2016). End users validate warning information from official channels through triangulation from informal, trusted sources (Mileti and Sorensen 1990; Brown et al. 2016). Notably, research on evacuation behaviours in Indonesia revealed that information shared by friends and relatives significantly influenced evacuation choices, while official warnings had little to no motivational impact (McCaughey et al. 2017).

Anticipatory action, particularly those actions facilitated by aid agencies for the most vulnerable households, also require that warning information and messages are disseminated in culturally appropriate ways that are accessible by all groups, including those typically on margins (e.g. women, older people, people with disabilities, the illiterate/innumerate, etc.) (Peacock et al. 1997; Drobot and Parker 2007; UNISDR 2015). This includes translation of messages and technical jargon into local languages and dialects (Morrow 2009; Benavides and Arlikatti 2010; Benavides 2013; Arlikatti et al. 2018).

In addition to all of this, the literature clearly indicates that direct participation in EWSs by vulnerable communities is the strongest predictor of AA (Barrett et al. 2004). In Bangladesh’s experience with Cyclone Alia, those who participated in developing and administering the EWS had acted early in anticipation and preparation compared to those who had not participated (Ahsan et al. 2016). Additionally, there is strong evidence from America (Hoekstra et al. 2014), Europe (Priest et al. 2011), and Bangladesh (Paul et al. 2010) to support the influence of behaviour-change programs on AA upon receipt of an early warning. Conversely, there is ample evidence from India (Arlikatti et al. 2018) and China (Donovan et al. 2018) illustrating the relative ineffectiveness of top-down, technocratic early warnings.

EXAMPLE I: EWS Ownership in the Bicol

One example comes from the experience of Typhoon Dante in the Bicol River Basin of the Philippines. Prior to the typhoon’s landfall in 2009, residents were involved in rainfall monitoring using rain gauges installed near their homes. This information along with other data was used to develop a flood model. Highly accurate predictions of the time, location, and severity of impending floods, coupled with early warnings, improved the responsiveness of local populations and significantly reduced the impact of Typhoon Dante. Research by Abon et al. indicate that the involvement of these communities in gathering rainfall data helped foster a sense of ownership of the EWS, improved understanding of local floods, and enhanced trust in the forecasts and warnings (2012).

Finally, early warning for early action must extend beyond notification to motivate and facilitate their preparedness. The existing psychological and social cognitive studies on motivations and intentions to prepare for disasters cover factors ranging from perceived benefits of preparedness (Najafi et al. 2017), trust (Sjöberg 1999; Stokoe 2016; McCaughey et al. 2017; Sullivan-Wiley, K. A.and Short Gianotti 2017), self-efficacy and locus of control (Martin et al. 2007; Baytiyeh and Naja 2016; Najafi et al. 2017) to social norms (Martin et al. 2007; Becker et al. 2015; McCaughey et al. 2017), response or action efficacy (Paton 2003; Grothmann and Reusswig 2006; Lindell and Perry 2012), and senses of belonging and place (Paton 2003; Kim and Kang 2010; Becker et al. 2015). While there is, at this stage, a significant amount of literature studying the social and cognitive aspects of intentions for preparedness behaviour, all of these studies assume a premise of resource and skill adequacy. However, there is evidence that even in the face of high trust in early warnings, high risk perception and high motivation and intention to adapt and prepare, a lack of resources, skills, and knowledge for preparedness will prevent it altogether (Pennings and Grossman 2008; Sjöberg 1999; Sullivan-Wiley and Short Gianotti 2017; and Wachinger et al. 2013). In a 2017 qualitative study of unprepared and prepared people by Najafi et al. in Tehran, monthly income level was a statistically significant and positively correlated predictor of actual disaster preparedness behaviour. Meanwhile, a host of other factors, including gender, educational level, household size, home type, home ownership and being the head of household, were not statistically significant. The study concludes by stating, “therefore, an effective intervention will not only have to encourage people of the desirability of DPB [disaster preparedness behaviour], but also to provide them with the skills and means to do it.” (Najafi et al. 2017, n.p.). Our research seeks to inform the gap between growing interest in anticipatory action and the behaviorally-informed early warning systems and forecast-based financing mechanisms required to enable that action.

Methodology

Given the results of the literature review and the critical linkages of early warnings with early action, the study for this chapter employed qualitative methods (a more focused literature review) to better understand the if and how AA and forecast-based action models like the one developed by the Start Network help to enhance early action behaviour by vulnerable communities. To conduct the literature review, the authors considered peer-reviewed journals, published books in print form, as well as grey literature and research reports issued by practitioner NGOs, UN agencies, research institutes, and donor agencies.

The search period was limited to sources published after 1983. This date was chosen based on the triangulation of the dates and time periods associated with a confluence of several factors: (1) heightened attention to improving early warning systems after the false alarm of the Soviet nuclear early warning system “Oko” that almost ignited a nuclear war in 1983, (2) the destruction of the 1983 Japan Sea tsunami (Shuto and Fujima 2009; Bernard and Titov 2015) and a particularly strong La Niña event in 1982-1983 (Gerrity et al. 2023) and renewed interest in early warning improvement, (3) advancements in landslide early warning systems (Guzzetti et al. 2020) and severe storm forecasting (McCoy 1986), and other weather prediction systems (Shuman 1989) in the early 1980s. Source literature was limited to those that discussed low-income country contexts, with special allowance made for those that discussed high-income contexts in relation to behavioural elements of EWSs. These criteria yielded nearly 300 peer-reviewed journal articles, 96 works of grey literature, and eight books.

It should be noted that experiences and perspectives of emergency managers and the humanitarian aid industry and its inner workings are highly dependent upon the age and gender of staff working within it, with older, male adults having the most experience with the status quo and most resistant to change in the industry. Likewise, cultural and contextual differences of affected populations directly inform and influence societal perspectives of natural hazards, how they function, and why they strike, and whether there is any action efficacy, self-efficacy, or agency to address them. Geographic differences were important to capture in terms of the range of natural hazards affecting vulnerable populations. Therefore, data collected by Start Network involved semi-structured interviews conducted with 14 Start Network participants recruited through purposive sampling to ensure representativeness of ages, gender, geographic, cultural, and contextual differences, and organisational roles. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed, allowing for detailed analysis. Transcriptions were evaluated using an open coding technique to identify key themes and patterns. The coding process followed the principles identified in the literature review, allowing themes to emerge from the data. Once consensus was reached on coding, the data were organised into thematic clusters representing overarching patterns and concepts. These themes were further refined to core themes that encapsulated the essence of participants’ experiences. Ultimately, this analysis yielded a rich understanding and provided insights into the complexities of participants’ perspectives and the broader operational contexts shaping their experiences.

In addition to conducting semi-structured interviews with participants, document review was employed as a supplementary data collection method to enrich our understanding of the organisational context under study. Documents published by the Start Network and its members, such as annual reports, crisis response summaries, case studies, research reports, and post-deployment evaluations were systematically collected from the organisation’s archives. These documents provided valuable insights into the historical development, institutional practices, and discursive frameworks shaping organisational dynamics. The document review process involved careful examination and coding of textual materials, identifying recurring themes, key events, and discursive shifts relevant to our research questions. By triangulating data from interviews with insights gleaned from document analysis, we aimed to enhance the depth and comprehensiveness of our findings, capturing both the subjective experiences of participants and the broader socio-cultural context within which organisational processes unfold.

Findings

Analysis of the literature revealed four main themes concerning how EWSs are utilised to inform anticipatory early action and the factors that condition that utilisation. These include:

- Participation of end users in EWS development and administration to enhance trust in warnings,

- Localization and contextualization of EWS function and messaging,

- Orientation of EWSs toward promotion and facilitation of action,

- Vertical linkages of local relief actors to donors and international stakeholders at higher scales.

The following sections will discuss the findings of primary data collected and analysed from a range of Start Network staff and stakeholders that respond to these four main themes identified in the literature review, organised by scale: Local, National, and Global. The scalar organisation of the findings is helpful in highlighting the scale-dependent interactions of early warning systems and anticipatory action, different stakeholders, and methods of working.

Anticipatory Action at the Local Level

Participation for Familiarity and Trust

Early warning systems are only as good as the anticipatory action it promotes and enables. As the literature review highlighted, one of the primary barriers for vulnerable populations heeding early warnings is a lack of trust in the messages provided, the accuracy of the content of those messages, and sometimes even the stakeholders issuing those messages (Brown et al. 2016; Fakhruddin et al. 2015; McCaughey et al. 2017; Mileti 1999; Mileti and Sorenson 1990; Paul et al. 2010; and Priest et al. 2011). Start Network’s more recent experience with 2023’s Cyclone Freddy in Madagascar confirms this. Focus group discussions carried out during an impact evaluation of Start Ready’s mobilisation highlighted within the community an overall lack of awareness and understanding of the Disaster Risk Financing (DRF) mechanism itself and a lack of trust and reluctance to act on the system’s warnings (Start 2023).

This stemmed from the fact that community members did not participate in the development of the warning system managed by Madagascar’s meteorological agency Meteo Madagascar[3], nor were they involved in communicating and propagating that bulletin to the wider community once it was issued.

Participation by local communities for purposes of building trust in the system is not limited to the early warning system itself, but extends to planning and administration of the AA system. Data from semi-structured interviews with Start Network staff from the Philippines and Bangladesh support this explicitly. In the Philippines, Start Network staff purposefully supported grassroots consortiums of civil society organisations (CSOs) through the contingency planning process of Start’s AA model, arguing that local, community-level CSOs and NGOs are far more comfortable and competent with community organising. In Bangladesh, participation of community members in measuring rainfall using rain gauges gave direct, immediate, and transparent feedback opportunities for community members to compare forecast accuracy with their own observations. Community engagement in forecasting and supplementing forecasts with their own on-the-ground information not only demonstrated the community’s understanding of the system, but helped community members adjust their own expectations of forecast accuracy (up or down) based on data they themselves collected. This had a mitigative effect on loss of trust when forecasts were inaccurate.

Trust of local communities in EWSs and AA can also be eroded by perceived imbalances or disparity in the provision of anticipatory funding or material aid. This is particularly problematic when hazards extend over a large area, as in the case of drought. In 2022, nearly every district of Zimbabwe was projected to experience some level of acute food insecurity due to worsening drought conditions. Prior to the onset of drought, Start Network members performed a participatory vulnerability assessment to target households for anticipatory funding based on the expertise and prior understanding of members, along with data concerning particularly vulnerable areas, as well as projected estimations from FEWSNet and similar outlets. At the grassroots level, targeting was facilitated by relevant Departments of Social Development across all regions, followed by the involvement of community-level selection committees comprising leaders and households at the village and ward levels. This approach ensured a perceived parity in accessing humanitarian aid, while also giving priority to demographics such as the elderly, individuals with disabilities, widows, households headed by children, orphans, and those experiencing low agricultural yields.

Another opportunity for transparency and building trust in EWSs and AA is in the definition of triggers: the point at which early warning systems engage and interact with AA mechanisms. REAP defines “trigger” as “a predetermined criterion that, when met, is used to initiate actions.” (Knox-Clarke 2022, 26). In the case of early warning for early action, the triggers often take the form of meteorological thresholds (e.g. soil moisture levels for drought, rainfall or floodwater levels, wind speeds and proximity to land for tropical storms, etc.) and initiate actions ranging from preparedness to the release of funding for AA. Interviews with Start Network Bangladesh staff indicated that the increased use of community-owned triggers helped enhance understanding and acceptance of technical, scientific meteorological knowledge (pers. comm., November 28, 2023). If a community can agree on triggers, how to measure those triggers, and how to communicate when and how those thresholds are exceeded, trust in early warnings and the associated early actions are more likely to occur.

Participation for Contextualization and Translation

Likewise, the involvement of potentially affected populations helps to ensure that warnings are properly contextualised and translated into trustworthy and actionable messages (Peacock et al. 1997; Drobot and Parker 2007; Morrow 2009; Benavides and Arlikatti 2010; Benavides 2013; UNISDR 2015; and Arlikatti et al. 2018). Interviews with Start Network Madagascar and Start Network Bangladesh indicated the critical importance of incorporating and leveraging local, indigenous knowledge (IK) for better uptake of forecasting and warning information (pers. comm., February 7, 2024; pers. comm., November 28, 2023). Another example from an interview participant in the Philippines reported the importance of translation of highly technical information into local dialects for typhoon preparedness and early action (pers. comm., February 1, 2024). In the case of drought early warning for early action in Zimbabwe, Start Network found that participation of the community in development of its local DRF system actually changed the community’s planning and preparedness actions before drought was even declared (Jaka et al. 2023). In this case, the existence of a PC-EWS linked to financing provided a sort of “safety net,” helping to promote no regrets preparedness before any warning was issued or funding released.

Timing

When warnings are intended to elicit action, the preferred actions to be taken will often dictate how much lead time is necessary to enable participation. For example, Start Network’s experience with facilitating anticipatory actions in response to forecast-based warnings of Cyclone Biparjoy in Rajasthan and Gujarat, India in June 2023 illustrates this directly (Start and SEEDS 2023). An analysis of the joint international NGO and locally led NGO effort indicated that 100% of households who received warnings less than five hours prior to landfall prioritised basic necessities like food and water (Start and SEEDS 2023). Meanwhile, households who received warnings progressively earlier engaged in more diversified actions, indicating an underlying preparedness strategy. Warnings received 6-12 hours prior to landfall brought in housing reinforcements and evacuation behaviours. Individuals who received warnings 3-7 days before landfall were far more proactive, going so far as to relocate stored harvests and livestock to safer areas while reinforcing their homes and evacuating (Start and SEEDS 2023). One Start Network staff person reiterated this in an interview about his experience with AA in Bangladesh to riverine flooding. The individual commented that “if they [vulnerable households] get better lead time [of the warnings], they can do many more actions which can also contribute to DRR [disaster risk reduction], especially preparation for seasonal hazards.” (pers. comm., February 5, 2024). Clearly, desired early action behaviour must inform the minimum lead times provided by EWSs.

Likewise, the facilitative actions taken by NGOs to assist vulnerable populations with preparedness can dictate required warning lead times. In the case of drought early action in Zimbabwe and Senegal in 2021/2022, Start Network members distributed cash as a support mechanism when drought conditions exceeded pre-established thresholds (Start 2023). An evaluation of that effort revealed that cash distributions needed to occur sooner to allow households to then go and take anticipatory actions, including storing of agricultural reserves, weaning and relocating livestock, and even using drought resistant farming approaches where possible.

Dignity and Social-Emotional Benefits

Data from interviews conducted with Start Networks staff in Bangladesh, Madagascar, Philippines, and India indicate that receiving emergency relief for affected populations, particularly those who encounter disasters more frequently, is embarrassing and shameful, with direct and negative impacts on their own sense of human dignity (pers. comms., February 7, 9, and 13, 2024).

Those same interviewees, however, also pointed to the ability of AA and FbA approaches to give renewed senses of agency to community members to act themselves prior to disaster events and avoid having to wait helplessly on humanitarian aid to arrive after the event. While overcoming the tendency to wait on aid that had been so reinforced over the years of disaster history in these locations was difficult, these experiences of preparedness helped to alleviate loss of dignity and doubts about the effectiveness of early warning systems in these communities. This was particularly effective when AA and FbA funding and support were matched with the preparedness actions desired by community members. Interviews with Start staff in Bangladesh specifically noted the effectiveness of funding the relocation of people’s homes away from riverbanks in preparation for cyclones and flood events (pers. comm., February 9, 2024).

Anticipatory Action at the National Level

As mentioned earlier, Start Ready prepositions funding for crises that happen with regular and predictable patterns of recurrence like floods, droughts, and heatwaves. When a threshold, pre-agreed at the national level, is met, the release of funding is triggered. This funding is intended for NGOs to implement pre-designed contingency plans corresponding to forthcoming predictable climate risks. In the first Start Ready Risk Pool,[4] financial protection was provided to 590,019 people in eight countries in regards to 10 climate risks. From May 2022 to April 23, Start Ready was activated or triggered eight times. The trigger not only gave aid organisations the advance resourcing that they needed to protect against the forthcoming hazard, it also provided the knowledge required for early response, utilising locally led choices of early action. The activations occurred across a range of contexts, from drought in Zimbabwe, Senegal and Somalia to heatwaves in Pakistan; from a cyclone in Madagascar to riverine/fluvial flooding in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. A total of £2,854,861 was disbursed to 15 agencies as a result of thresholds exceeded, funding 19 projects and directly serving around 283,275 people before, during, and after hazard or impact onset.

The level of design and time invested to create the Start Ready mechanism requires substantial technical expertise and consultation. Experience varied from country to country, but nearly all Start Ready members highlighted the significant commitment required to identify and analyse the knowledge needed to develop the triggers used in justifying the release of funds. Key stakeholders and consortium members worked with the communities to forecast the risk, while technical experts, in areas such as GIS and remote sensing, provided additional scientific knowledge to design a risk modelling and analytics system. This system provided the statistical analytics on the likelihood of an event happening over a set timeframe of 12 months. It is this model that is referred to as the Disaster Risk Financing (DRF) system, and the timeframe attached to the activation of funds is known as the return period. (See Text Box 4 for Bangladesh Case Study). Based on the level of uncertainty in the forecast approach, the lead time of a trigger point may vary. For example, contingency plans for fast onset hazards like cyclones must fit within a three day window, while those for slow onset hazards like drought may occur over months.

Complexity in Communicating and Shifting “Aid Norms”

Our research revealed the importance and challenges of communicating the values, goals, and processes of anticipatory financing to humanitarian-trained cadres. Traditional humanitarians implementing an AA programme must learn new skills and knowledge and adjust the traditional worldview of post-disaster relief, to incorporate a future outlook of protection and early warning, as opposed to a lifesaving “in-the-moment” perspective. In the Philippines, one informant stated “There was a lot of resistance when we did the contingency planning, especially for those seasoned humanitarians. When you talk about contingency plans, we only talk about what will you do after the cyclone and what will you do for the worst-case scenario. But with this, what we did was ‘let’s talk about what you want to do 72 hours before’.” (pers. comm., February 2, 2024).

Furthermore, in Bangladesh, it became apparent that such a communications investment was core to ensuring engagement, building trust, and re-centring the locus of control. One interviewee stated, “We chose 4 districts and brought the national organisation on board, not only asking them what to do, but bringing them in the design phase. […] And now you see they are more confident in doing anticipatory actions. Before that, they were shaky, they didn’t know what’s going on, how to do that, what is the forecasting, what is the threshold? They had zero level of understanding on that kind of thing. But now they are more confident, and after our contingency plan preparation, they submitted their first anticipated action project and got funding. What we found is that members are more empowered, more engaged and eventually they have more confidence.” (pers.comm., February 13, 2024).

To support the roll out of Start Ready, the Start Network designed a tool called Building Blocks. Building Blocks is a step-by-step guide for the participation of local communities and CSOs in designing and building a disaster risk financing system and contingency plannning. However, there was a mixed response in its use. Many of the stakeholders who were approached were classically trained humanitarians. Start Network members found it difficult to get others to understand the mechanisms for the system and design the triggers. Most of the concerns revolved around the validity of the trigger and the consequences of what happened if it was wrong. Instigating no-regrets approaches to the design of the contingency plans helped, in part, to overcome these issues. This was complemented with a contingency when Start Ready allocated a sum of money to cover the “basis risk,” or the difference between anticipated and actual outcomes. For the Philippines, Building Blocks was overall a positive experience of developing a framework that helped collect data, scope the system and determine the niche and gap that Start Ready could fill. However, their key learning was that the Building Blocks process had been designed as linear. Their experience with the process was more cyclical, bringing back learning and insights at different stages both to strengthen the analytics model which designed the triggers and to improve contingency planning (pers. comm., February 2, 2024).

Creating the Enabling Environment for Anticipation

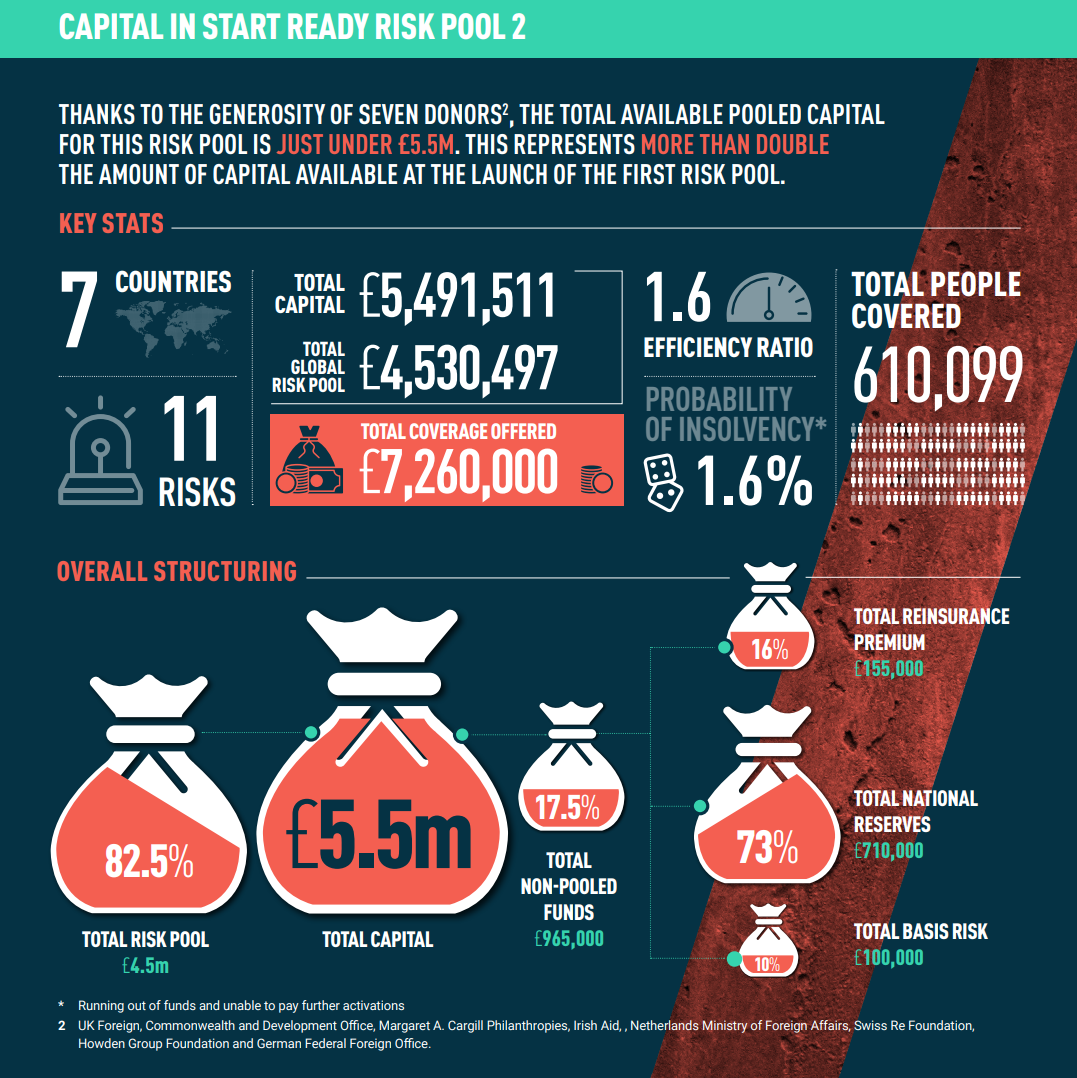

Figure 2 shows how the first risk pool was structured, enabling different parts of the fund to serve different components of the anticipatory financing approach. The structure is broken down into three areas: a) funds to be released for early action with every activation, b) the basis risk fund, and c) the national reserve funds that preposition support for the smooth outworking of a contingency plan.

During the research, it became apparent how important national reserves were in creating an enabling environment for effective contingency plans and PC-EWS. In the Philippines, one informant stated, “The national reserve is where they start targeting and identifying who would be the beneficiaries, communicating this to the community. All of this is how contingency planning and the national reserve make sure that we have the right data, the right information, and the enabling environment to activate the system” (pers. comm., February 2, 2024). In Bangladesh, evidence was given that the national reserves were used to prepare the cyclone shelters to receive people, giving communities confidence that if they chose to go to the cyclone shelter and leave their homes behind, they would have space and access to basic essentials such as food, functional latrines, and access to electricity (pers.comm., February 13, 2024). More importantly, these actions were identified during the contingency design process, (i.e. identified and owned by the communities). Very often, the investments of these national reserves were also designed on a “no regrets” basis. Even if there was no trigger, the investment to repair latrines or secure access to electricity had long term benefits and supported the day-to-day functioning of the building.

Start Ready members also involved local governments in the design and activation of contingency plans, to good effect. For example, in the Philippines, one informant stated “the municipal planning officer told me yesterday that the DRF team really influenced the local government unit, and they are planning to replicate what we are doing because they really appreciated the process that we have made that we have done from the first to the implementation. That’s why they are so very thankful. They received positive feedback from the recipients from the community and that made them really appreciate the concept of AA” (pers.comm., February 2, 2024). In Bangladesh, sensitisation to AA also came through the contingency planning processes. Giving stakeholders, especially the government, a contingency plan and risk map enabled them to easily identify vulnerable communities, levels of resourcing needed, and types of actions to do before and after a crisis (pers.comm., February 13, 2024). They were also mobilised to see their role alongside communities. As a result, they recognised they too could use the knowledge from the activation to inform the release of their own resourcing and government responses, aligning goals and operations with CSOs and NGOs to deliver services when an activation occurred.

Catalytic opportunities arising from the development of the contingency plans include better coordination and acceptance of local CSOs and NGOs with other aid actors and agencies. In Madagascar, mobilising the members around a DRF created interest from multiple other aid actors, including the government and INGOs. This, in turn, led to better awareness and acceptance of the role and knowledge that local members had to offer. Equally, the interviewees observed how data was not freely shared. “We need data for the forecast, data for the coordination, and vulnerability data for the different zones. Start Ready requested the data, and while some have been keen to share, others have not because they think the data belongs to them. This is a real issue as we may need to gather that data for us to launch a Start Ready activation” (pers.comm., February 7, 2024).

Anticipatory Action at the Global Level

The aspiration for Start Ready governance is to be as locally owned as possible. However, due to the multi-country nature of the risk pool and the sensitive decisions on how to prioritise risks and the populations to be covered, the decision making is undertaken by an internationally selected governance committee. This committee is composed of risk and insurance experts, independent consultants, and Start Network members, and it is the latter that represent the local voices and the communities they serve. In the first two years of Start Ready, the governance committee experienced the same heavy complexity of understanding and socialisation on the concepts and opportunities of AA as the communities and local organisations did. Consequently, decision making was slow, and occasionally difficult to keep transparent. Decision making frameworks giving boundaries and criteria for fair and equitable decision making had to be developed to give assurance that the local voice continued to be a central tenet of decision making.

The process of deciding how much insurance coverage each country has against the risks they identify is based on their contingency plans and risk modelling. This process is lengthy and demanding on the key stakeholders in each country. Once that information is received from the countries, the decision making is broken down into two parts. The first part was where the principles were decided (e.g. what level of “stretch” is appropriate, and what level of risk is acceptable). Stretch defines the ability of the risk pool to cover a larger volume of risks than the funding allows over a 12-month period. This is based on the fact that statistically not all of these risks will initiate in one single year. The risk of going “bankrupt” is then covered by paying for reinsurance. It is the committee’s responsibility to decide how risky they want to be by defining the percentage likelihood of going bankrupt which is acceptable to them. As part of this process to make this decision it was not unusual for the committee to realise they need extra information to help make sense of the modelling and to give them confidence in decision making. The second part is to work through the results of the statistical modelling to decide how much coverage can be allocated to each country.

Nearly always, the volume of funding offered to a country was less than requested, leaving the Start Ready members to go back and identify the priority locations they wanted to work in. This undermined confidence and expectations in the system. Confidence was also undermined when, during the first pool, an activation for Pakistan “misfired.”[5] When the statistical analysis of the modelling has failed, Start Ready has set aside a small fund of money to support the communities affected even if they can’t draw down on the funding from the coverage they have been allocated. This is called “basis risk.” Locally, Start Ready members believed that the failure to receive a payout for the Pakistan floods of 2022 was a design fault of the risk model, and they were entitled to this “basis risk” funding. However, further investigation from technical experts stated the model was correct as it had been designed for fluvial risk (risks associated with lower course river events) and not pluvial risk (risks from flash flooding which had in this case been the trigger for the lower course flooding). Such lessons required diplomatic management between governance and local members to ensure that there was continued faith in the system, plus to prevent ripple effects undermining confidence with the local partners. The locus of control and the ability to believe that resourcing will be available when a trigger occurs is foundational to cultivating trust in the design, development and outworking of PC-EWS.

As a membership-based organisation with over 90 different participants from countries covering five continents, Start Network’s ultimate structure is designed to be a network of networks, governed by leadership from nationally-based hubs. These hubs are currently being developed as legally registered, nationally owned entities composed of community, national, and international NGOs. The mission of Start Network is that the current international aid system is to demonstrate alternative models that can operate at scale. This direction could ultimately disrupt the “big boots” approach to internationally led response, with locally-led, proactive humanitarian activities managed by local leadership. Thus, Start Fund and Start Ready aim to have locally led design and decision making embedded into their systems, protocol and procedures (See Figure 3). However, there are limitations to this approach, including the role of the donors.

Start Ready donors are currently a combination of bilateral governments and foundations, including the European Union, UK Aid, Netherlands, and Irish Aid. Maintaining accountability and compliance for such donors when implementing the risk pool has complexities, not least to do with high compliance and due diligence when implementing with local partners. The added dynamic is that the risk pool is not insurance. In lay terms, insurances are based on a pool of capital which permanently exists to support payouts. This capital pool fluctuates but is topped up from premiums and investors who later hope to profit from unrealized risks. A risk pool is a pool of capital deliberately designed to be distributed each year against a set of pre agreed risks. Ultimately, the donors expect the funding they have put into the risk pool to be drawn down within that year with nominal amounts of underspending, demanding a fine tuning of technical expertise.

Discussion

Anticipatory Action at the Local Level

We have shown with the literature that EWSs have traditionally focused on providing forecast messages using meteorological and mobile communication technology, with the assumption that vulnerable communities would utilise that information to prepare themselves effectively. Any emphasis in the warning messages on action primarily focused on informing early crisis response efforts by governments and donors. The apparent failures to stimulate AA by vulnerable communities after receiving warnings have prompted calls for more people-centred early warning systems (PC-EWSs), aiming to involve affected populations, adapt messages, and remove barriers to action. Recommendations emphasize cultural relevance, usefulness, accuracy, equity, and credibility. However, despite these efforts, evidence from behavioural science suggests PC-EWSs must move beyond a focus on warning messages, to consider broader factors like available actions, barriers, motivators (financial, societal, gender-based), and perceived consequences (positive and negative) of those actions (Sjöberg 1999). The following sections will discuss the ways in which coupling AA approaches with early warning system development and administration at the local level helps to promote and facilitate the very preparedness activities that those EWSs are intended to elicit.

We have shown in examples ranging from Bangladesh to the Philippines to America and Europe that participation of vulnerable populations in the development and administration of PC-EWSs is one of the most effective ways of overcoming mistrust in the messages and making forecasting processes more transparent, accessible, and relatable. In addition to participation in the development and administration of the warning system itself, anticipatory action and forecast-based action (FbA) approaches coupled with PC-EWSs provide additional opportunities for community participation to build trust in the system. Our evidence supports a requirement for full transparency, from the involvement of local communities in the collection of hazard data, the development of/and agreement on triggers for the release of anticipatory funding and aid, and the identification of vulnerable populations for receiving aid.

Similarly, the focus of more participatory early warning for early action must be hyper-local, especially when the hazardous event extends over a large impact area (UNISDR 2015). Drought, in particular, presents a challenging scale where forecasting and early warning are done at a national or even regional scale, yet AA processes must still occur at local levels in order to facilitate and promote effective early action. Our evidence highlights the importance of perceived parity by local communities in aid distribution or, at minimum, perceived accuracy in distribution of aid to those who need it most. This is critical in early action in response to large-scale hazards like drought.

The creation, agreement, and monitoring of triggers offer yet another opportunity to help build the trust of community members in early warning messages. This becomes especially valuable in instances when anticipator action and aid are not released. Full transparency for local populations to understand what the thresholds are, why they were not exceeded and why aid was not dispersed, even when isolated conditions seemed to warrant it, helps mitigate loss of trust in the systems for future use.

Contextualisation and translation of early warning and preparedness information and messaging is often limited to language translation and alignment of messaging with platforms available locally. Often overlooked in this technocratic understanding of contextualisation and translation is the incorporation of indigenous knowledge (IK) (Morrow 2009). Our evidence highlights the value of IK to ensuring that messages are trustworthy and actionable.

Furthermore, linking EWSs with financing frees communities to take preparedness action without regret of lost resources if an event doesn’t occur, is not as severe, or strikes elsewhere. The Risk-Informed Early Action Partnership (REAP) defines no regrets action as “disaster risk management actions taken in advance of a hazardous event that provide benefits to the receiving population irrespective of how or whether a disaster occurs” (Knox-Clarke 2022, 21). In this sense, these communities in Zimbabwe felt that they could engage in early preparedness action without fear of sunk costs precisely because trust levels in the system were buoyed by their participation in its administration. In the case of drought in Madagascar in 2021, the provision of cash transfers to 1500 vulnerable households by Start member Welthungerhilfe helped families not only stockpile food and supplies, but also prevented engagement in negative coping strategies (e.g. selling off productive assets or deciding not to pay school fees) (Semet n.d.). As a principle, AA programs should promote and fund no regrets actions in order to facilitate initial openness to trusting PC-EWSs.

In addition, there is widespread agreement amongst the early warning community that warnings issued earlier have a higher likelihood of being inaccurate, making them less trustworthy. Yet, experience from implementing AA mechanisms indicates that the timing of those warnings can promote and facilitate early action, nonetheless (Start Network 2023; Start Network and SEEDS 2023). Our evidence suggests that warning messages received a minimum of six hours ahead of the hazard event are more likely to result in more diversified preparedness and evacuation behaviours. Earlier warnings do open up the possibility of false warnings, but with enough measures in place to ensure transparency in the process, the loss of trust can be mitigated. Ultimately, though, the desired early action behaviours must inform warning lead times. More research and learning is required to provide a more nuanced approach to warning lead times.

While the chapter thus far has focused on the technical and mechanical aspects of AA and FbA approaches coupled with effective PC-EWSs, the social and emotional benefits should not be overlooked. The affect heuristic, or the tendency to rely on emotions for making decisions rather than concrete information, has received a lot of attention from risk and disaster management researchers (Tversky and Kahneman 1974; Chandler et al. 1999; Loewenstein et al. 2001; Slovic et al. 2004; Slovic et al. 2005; and Tierney 2014). This, in conjunction with the freshly experienced trauma of disaster impacts on one’s household, compounds social-emotional health in frequently affected populations (Lating et al. 2023). Our findings indicate that PC-EWSs and AA can promote human dignity by giving renewed senses of agency and action efficacy, or the belief that one’s actions will be effective for their intended purposes. More attention should be given to these social-emotional benefits of AA, both in terms of future research and in real world implementation.

Challenges with Anticipatory Action

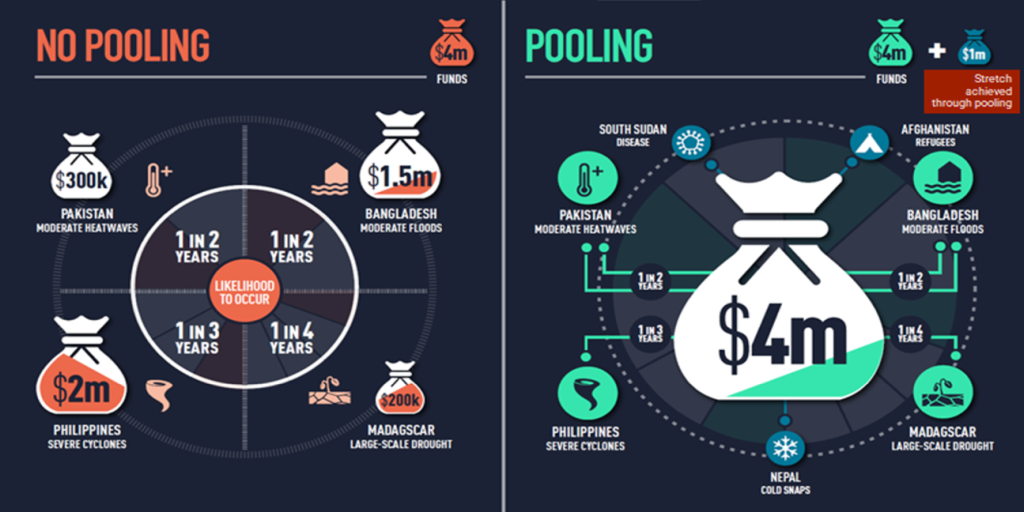

At the local level, aside from traditional challenges associated with distrust in early warnings and the communication of those warnings to the most vulnerable segments of the population, the data from this study indicate that the process of targeting individuals and households for forecast-based assistance is fraught with difficulties. In most of these vulnerable communities, households are very accustomed to disaster impacts and are, therefore, familiar with typical operating procedures of humanitarian aid agencies. However, as this chapter has already discussed, AA and forecast-based action operations and financial flows are distinctly different from the aid industry’s modus operandi. This is not only true for aid workers, the agencies they work for, and the donors that fund them. This is acutely true for affected populations. How do aid agencies working in AA and forecast-based action approaches target vulnerable households prior to the impact of a disaster? More to the point, how do agencies do this without causing confusion and tension within the community when some households are targeted for assistance while other households similar to one another in socioeconomic terms are not, particularly when disaster impact is yet unknown? Start Network’s experience in Madagascar illustrated these challenges in a cyclone season that saw six tropical cyclones and storms impact the island within a four-month span affecting nearly a million people. This necessitates the use of risk pooling techniques (for more on risk pooling, see Text Box 2 below. The vast geographic area and population figures far exceeded the aid industry’s ability to support all those affected. So decisions had to be made in terms of who to target. While interview data from Start Network Bangladesh indicate the need to work with local NGOs on sensitive targeting methodologies (pers. comm., February 1, 2024), more research is needed to better understand how to properly target vulnerable households for AA and forecast-based action while avoiding community tensions and conflict.

TEXT BOX 2: Complexities of Risk Pooling

Risk pooling enables the protection of a larger number of individuals within the constraints of limited funds by leveraging the natural diversification of risks. This means that not all countries will face major crises simultaneously. Instead of maintaining separate funds earmarked for specific crises or countries, which may not always be fully utilised, pooling and layering risks, often through insurance mechanisms, allows for a more efficient allocation of funding, stretching it further. Successful risk pooling necessitates the expertise of technical and actuarial service providers. By participating in risk pooling, member NGOs and stakeholders can save more lives at a reduced cost. Start Ready introduces a system for pooling risks and funds across various contexts, countries, and hazards for the first time, thereby expanding protection to more people vulnerable to foreseeable crises globally and optimising resource allocation. However, to ensure the sustainability of Start Ready, it is essential to reinsure the risk pool, thereby guaranteeing payout even in exceptionally severe years. This involves using a portion of trigger funds to purchase a premium, which would unlock a significantly larger volume of funds for the pool in the event of simultaneous triggering of all DRF systems. Additionally, insurance may be utilised to reinsure the pooled funds. The overarching vision is to establish a locally-led humanitarian system that remains accountable to crisis-affected populations. Ultimately, this entails developing a global financing framework that mitigates risks, anticipates crises, and proactively implements innovative, context-specific, and sustainable solutions for affected communities.

Page 5 Start Ready handbook

Anticipatory Action at the National Level

Having examined the impact that funding for AA has on positive behavioural choices resulting from PC-EWS, it is important to note the relationship that NGOs have as the facilitators of this anticipatory financing. The Start Ready activations discussed above illustrate the role of the NGO (both national and locally embedded aid agencies) as intermediaries of power, resources, knowledge, and partnerships and the indirect, complementary support to the effectiveness of PC-EWSs. Learning from Start Ready’s own monitoring and evaluation mechanisms, highlights the importance of national level actors in creating the enabling environment for positive early action behaviours and the importance of understanding the actual determinants of these behaviours, not just basing the contingency plan design on perspectives of risk. Belief systems, worldviews and social norms are factors that should be considered, along with clear contextualisation and fostering trust. To ensure effective outcomes where communities are protected, local actors need to co-design with locally determined decision-making protocols for the DRF model, which in turn will ensure PC-EWS are locally owned and designed.

Meanwhile, our research demonstrates that the expectations that AA saves time compared to the intensity of the design and implementation of an emergency response are misplaced. Time demand placed on humanitarian practitioners is hard to quantify as it varies from emergency to emergency, but the development and maintenance of a DRF model requires a similar level of engagement in data gathering, design and analysis. This is especially true when ensuring that the voices of the most vulnerable are heard and addressed. It is easy to see how humanitarian practitioners, often acting in siloes, struggle to collaborate when confronted with immediate or imminent humanitarian needs. This is compounded further by an international aid system that is designed to activate only at the point of impact and asset loss.

The Value of Multi-Stakeholder Approaches

In light of these observations, it is understandable then that the mechanism of Start Ready is complicated to communicate, especially in a way that is simple to transfer across languages, international perspectives and local management practices. One approach to overcome this complexity is to develop the DRF and associated contingency plans with consortiums of multi-level stakeholders, including local government, aid actors and local civil society organisations. It is a difficult exercise to bring such a diverse range of actors together, especially when their agendas, motivations and values are broad and often divergent. It requires relational and facilitation skills, time, and resources. Nonetheless, such collaborations are more effective with communities when gathering information, making those communities better equipped to assess the likelihood and impacts of mild, moderate and extreme events against a series of prioritised risks. This helps to ensure that the plans are locally contextualised around vulnerability, needs and the available skills, knowledge, and experience of the communities.

To illustrate, multi-stakeholder approaches have proven key for both Bangladesh and the Philippines. The consultations and coordination meetings helped stakeholders understand and contextualise AA and the value of Start Ready. For Bangladesh mentoring, coaching, and sharing experiences of how DRF systems worked helped communication and acceptance. Interesting to note that contextualisation was not just restricted to contingency planning and the development of the DRF model, it also was important to contextualise how Start Ready could work in a location from the outset.

CASE STUDY 1: Case Study on Bangladesh DRF development

Start Fund Bangladesh is a civil society-managed network of 46 national and international NGOs in Bangladesh which comes under the umbrella of Start Network. In Bangladesh this consortium chose to have a local Start Fund as its core mandate. This contrasts to other Start Network countries where the focus of operation is to bring local and international organisations together for the sake of collaboration, and then determine what is the core mandate. Modelled on the Start Network’s successful Start Fund, which disburses funds within 72 hours of a crisis alert, the central principle of Start Fund Bangladesh is to decentralise decision-making and allocation of resources closer to the community.

Start Fund Bangladesh were very keen to be an early pilot country for the first Start Ready risk pool. Socialisation and initiation into what Start Ready was came through the Building Blocks tool to help design the DRF system. The risk assessment process involved Start Network members and local communities engaging in a prioritisation exercise to evaluate climate risks. These risks were measured and prioritised based on historical experience, predictable risks (such as geographical and hydrological factors), forecastable risks, current trends, and funding gaps. Risk analysis was carried out either with external providers or internally, with support from the FOREWARN (Forecast-based Warning Analysis and Response Network) platform—an initiative of Start Network that brings together experts and forecasting information providers with humanitarian and community representatives.Decision-making on risk thresholds—mild, moderate, and severe—was a collective effort involving members and local communities, balancing technical advice with local expertise. The approach focused on: facilitating cross-learning; evidence generation; capacity sharing; creating inclusive spaces for marginalised communities; and establishing flexible minimum standards. It also fostered collaborative partnerships with governmental and other funding services, private sectors, research organisations, academia, and community networks.

Major considerations included risk knowledge, design thresholds, predefined actions, monitoring thresholds, and anticipatory actions. The resulting DRF model encompassed predictable triggered funding, innovative risk analysis, collective planning, scientific modelling, and pre-positioned financing to ensure readiness ahead of disasters.

To operationalize the DRF system, three studies were conducted to assess the country’s hazard context, vulnerability, financial flows during crises, and community perspectives. Utilizing science and data, models were developed to quantify risks in advance, which led to the development of the contingency plans. In 2023, a similar streamlined process was repeated to update the first DRF model which was then attached to the second Start Ready risk pool. While Bangladesh is a multi hazard country vulnerable to cold and heatwaves, earthquakes, storms and landslides, this specific DRF system was designed for floods and cyclones.

Expanding and Replicating AA

If we accept that effective AA must involve multi stakeholder partnerships, then brokerage of these types of partnerships must be prioritised. For the Philippines, strengthening the local government’s understanding of AA was key to its effectiveness and implementation. In its role as the central duty bearer to protect its citizens from disaster risk, the Philippines is well structured in its legislative framework for Disaster Management. As one partner stated, “We are humanitarian organisations, we’re not the government, we’re here to augment. Not to replace the government.” (pers.comm., February 2, 2024). Additionally, when bringing in new concepts, the voice of government (national and local) can facilitate or hinder acceptance. Local Start Network members are using effective communication and awareness raising on the value of AA as an advocacy tool to realign the way that the Philippine government allocates resources for disaster risk management. However, there is an ongoing need to separate out and contextually define terms such as resilience, disaster risk reduction and AA to social norms and local worldviews in such a way that, when local government programmes are designed and resourced, they have a clear understanding of how different aspects of disaster risk management complement each other.

It must be noted that not all governments are ready to include AA as a central tenet of their humanitarian practices. Frequently impacted populations have been conditioned to expect their government or the international aid system to provide aid when losses occur, not before. Communicating the benefits of AA to households is equally as important as communicating it to municipal authorities. To break the pattern of aid expectation, dependency, and centralised government coordination, both communities and authorities must be exposed to other possibilities. For communities, this includes understanding how perspectives of risk interact with belief systems, worldviews, and social norms, as well as understanding how national governance, freedoms, and rights enable or prevent community mobilisation and ownership. For PC-EWSs to be effective, they require trust that the data informing the early warning is accurate and reliable and that the possible preparations taken to protect themselves will be resourced either from within the capabilities of the community or from external sources.

Deepening Trust of Local Organisations

One way of undoing this “aid expectancy” comes from communities being mobilised to reveal their own capacities and capabilities. However, even if this occurs successfully, it also requires external stakeholders to accept and understand the communities’ role, capability and right to self-determine their own aid outcomes. In the instance of Bangladesh, this was demonstrated when information generated by the communities on the ground supplemented the technical forecasting. This individual stated “when it was a false alarm, it was members who were actually giving us the truth of the community. Your model is showing that the threshold is met, but we don’t see that kind of reality in the ground. So that’s how we adjusted the false alarm. This kind of confidence is only possible to show when they understand the system.” (pers.comm., February 13, 2024). Start Ready members know that trusting the communities and the local organisations who supported them is key in creating confidence and ultimately giving the communities a real sense of their role in the contingency plans. Several interviewees from multiple locations referred to contingency plans being “everyone’s document” as evidence of the importance of multi-stakeholder ownership.

Positive opportunities arising from the development of the contingency plans include better coordination and acceptance of local CSOs and NGOs with other aid actors and agencies. In Madagascar, mobilising the members around a DRF created interest from multiple other aid actors, including the government and INGOs. This, in turn, led to better awareness and acceptance of the role and knowledge that local members had to offer. Equally, the interviewees observed how data was not freely shared. “We need data for the forecast, data for the coordination, and vulnerability data for the different zones. Start Ready requested the data, and while some have been keen to share, others have not because they think the data belongs to them. This is a real issue as we may need to gather that data for us to launch a Start Ready activation” (pers.comm., February 7, 2024).

Capturing Learning and Improvement

Our research reveals a recurring theme: Start Ready Members and their local counterparts are not afraid to try new approaches, are not afraid to fail and constantly learn and improve. They had the courage to speak up in aid spaces where they were sometimes marginalised or not given the opportunity to influence decisions. Most importantly, the Start Ready members and their supporting local counterparts applied the lessons they learnt. Start’s experience in the Philippines provides two examples: (1) a near activation and (2) a full activation. Start members valued the near activation as a “dry run,” providing insight into where they could use national reserves more appropriately. Conversely, they learned more about the logistics of delivering their contingency plans from the full activation. Their circumstances required a 72-hour turnaround of actions in advance of a cyclone. While the communities requested cash assistance, the difficulties in getting this safely to the pre-selected beneficiaries proved difficult. As a result, they have moved to providing a cash payment card in advance, which gets an automated top-up when the trigger is met. Additionally, they have innovatively attached accident insurance to each card, which is sourced and supported from other government funds.

Our research also highlights how the mechanism of capturing forecast data from the communities is inextricably linked to cultivating trust and engagement from the community. For example, while capturing windspeed data was part of a PC-EWS, communities themselves wanted to gather data on water levels. Their experiences were that the floods affected them more than the windspeeds. Supporting the measurement of windspeeds helped get their engagement and building trust in the approaches. Clearly, building trust is not just about communities accepting behavioural changes and valuing and acting on early warning messages. It is also about facilitating trust in the motivations and ambitions of powerful stakeholders that control access to critical resources. The traditional focus on technocratic aspects of EWSs and even AA are only part of the picture. To ensure that AA proactively supports PC-EWSs, all stakeholders must be equipped and resourced in softer skills of partnership management, communication, relationship building and collaboration. Donors and other stakeholders with power and funding must design and support AA and PC EWS with this in mind.

Anticipatory Action at the Global Level

Having examined the role of Start Ready members and their local counterparts as effective facilitators of locally led AA, it is important to place this in the context of what is happening within the international humanitarian aid sector on the adoption and understanding of AA. The value of AA is becoming increasingly accepted as a new, viable international platform. These mechanisms include the Anticipation Hub[6] (a Red Cross initiative for humanitarian academics and practitioners), and the Risk-Informed Early Action Partnership[7] (REAP – a Red Cross initiative bridging the divide between humanitarian and development practice and supporting government interventions in AA). The financial return is also becoming more obvious. For example, the FAO’s Impact of Disasters on Agriculture and Food 2023 Report stated, “In the cases of Ethiopia and Mongolia, where the BCR is highest, investing USD 1 in AA led to over USD 7 in avoided losses and added benefits for beneficiaries” (2023, p.90). However, research commissioned by UK Aid, ODI and Centre for Disaster Preparedness also states, “to be effective, AA requires establishing and maintaining systems as well as capacity to implement. This means, more investment in preparedness and integration of early action plans or protocols with processes for preparedness and (early) response at national and local levels are needed.” [emphasis added].

Start Network’s own learning from experimenting with anticipation with Start Fund[8] highlights that behavioural change takes much more time than the duration of AA interventions (Start Network, 2018). Start Ready is prioritising its learning and evaluation approach to help plug the evidence gap. However, clear impacts from proven best practises within Start Ready will require 3-5 years’ worth of activations to truly know its worth. This includes the perceptions of local partners and communities and how they perceive their ownership within the mechanism and its clear value over and above traditional humanitarian response approaches.

Multiscale, Interdependent Implementation

Implementing effective anticipatory action mechanisms tied to PC-EWSs, as evidenced by Start Network’s experience, is a monumental and complex task. As has been shown, implementation at each scale carries its own set of complex tasks and associated challenges and impediments. However, to function effectively and efficiently, these tasks, and the various stakeholders engaged in them, must be coordinated across all three scales, each mutually reliant on some aspect of the other for proper function. As we saw with local level implementation, promoting community participation in and enabling locally-led community preparedness and early action and enhancing trust in warnings is not possible without the funding, resources, and expertise brought to bear by local and national NGOs. The complexities of the financing mechanism at the national level (with allowances made for risk pool capital and basis risk funding to mitigate differences between modelled predictions and actual outcomes), is itself based on data collected and analysed at the hyper-local levels. This data collection, however, is only made possible by funding allocated by members within the national reserve fund that facilitates seasonal readiness activities and capacity building. Meanwhile, the funding in these national financing mechanisms is made available by donors and grantors abroad, often from Global North governments and multinational agencies. Apart from financing, even the early warning systems employed in these mechanisms are a combination of data collected and analysed at every scale, from hyper-local vulnerability and weather data to national, regional, and international level satellite and atmospheric meteorological data. Compiling, collating, analysing, and translating all of this data into locally preferred, actionable, and fundable anticipatory action requires stakeholders coordinated at every level. In addition to bringing knowledge and understanding of the world of Anticipatory Financing, more must be done to enhance our understanding of how to broker and maintain these diverse multi-level, multi-stakeholder partnerships, and to further divest power as much as possible to the community level.

Conclusion

The biggest impediment to fulfilling the potential of forecasts is the transformation of acquired modern information into behavior modification. Information is valuable in so far as people are willing and able to act upon it. If people either cannot or will not change behavior in response to information they receive, then the information has no practical value. (Barrett et al. 2004).

This chapter, taken from the view of practitioners, explored whether effective PC-EWSs can be supported and mutually strengthened by localising decision making for the timely release of anticipatory finance and the behaviour modification and locally-led delivery of AA programmes it facilitates. We have highlighted the need for more people-centred approaches to early warning systems (PC-EWSs) due to the failure of traditional systems in stimulating early action among vulnerable communities. PC-EWSs aim to involve affected populations, adapting messages, and removing barriers to action. Recommendations stress cultural relevance, accuracy, and credibility, but evidence suggests PC-EWSs must also consider broader factors like available actions, barriers, motivators, and perceived consequences of those actions (Sjöberg 1999). We have argued that coupling anticipatory action (AA) approaches with local-level EWS development promotes preparedness activities intended by those systems. Start Network’s experience with AA helps highlight the local-level benefits of improved trust in warnings, contextualization and translation of those warnings, enhanced timing, and the dignity and social emotional benefits that come with enabling anticipatory action through funding and resources. All of this is critically supported at the national level with enhanced communication and coordination between private sector stakeholders and government officials and agencies.