5 Challenges in Preparing for and Responding to Disasters in Taiwan and The U.S.: Reflections from Practice and Academia

Ray Hsienho Chang, Ph.D.

Author

Ray Hsienho Chang, Ph.D., Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University-Worldwide.

Keywords

disaster preparedness, disaster response, international emergency management

Abstract

As a practitioner in Emergency Management (EM) who later transitioned into an EM researcher, Ray Chang has observed numerous challenges related to disaster preparedness and response. Throughout his journey in this field, he has engaged in various discussions addressing these challenge and identified potential solutions. This chapter serves as a platform to share the insights he garnered throughout his journey, proposing possible solutions to three fundamental questions: What are the things to prepare beforehand? Who should be incorporated in disaster planning processes? And how do people and organizations get ready for disasters?

The chapter employs a comparative analysis framework to review these challenges and questions based on practical experience, research projects, and audience engagement from Chang’s newspaper columns. To enhance the credibility of this chapter, meaningful connections between observations and insights from published, peer-reviewed research articles and pertinent U.S. Federal documents are included. Consequently, this chapter will review research articles on critical emergency management concepts. It will outline the methodologies employed in this chapter, present findings and solutions to the identified challenges, discuss the implications of this research in both academic and practical arenas, and conclude by offering suggestions for improvement and future research directions.

Three significant lessons emerge from this study: 1) advocating for broader perspectives in disaster planning; 2) establishing cohesive links between plans, training, and exercise; and 3) bridging the existing gaps between disaster researchers and practitioners. This chapter proposes several research topics for practitioners and researchers to collaborate on in the future, aiming to address the challenges in disaster preparedness and response.

Introduction

I began my career as a fire officer in Taiwan, initially serving as a lieutenant in a bustling fire station. This station handled nearly ten Emergency Medical Service (EMS) calls daily, along with a residential fire call every other day. As the city expanded, I transitioned to planning for critical infrastructure within my jurisdiction. This led to the development of Emergency Operations Plans (EOPs) for high-rise buildings with more than ten stories as well as for subway and train stations and the Hseueh-Shan Tunnel (an 8-mile structure in New Taipei City). Concluding my firefighting career as a captain in a fire battalion, I gained insights into the challenges of responding to disasters in Taiwan.

In my quest for better disaster preparedness, I read U.S. building and fire codes (e.g., National Fire Protection Association codes) and gained knowledge from the disaster management literature. However, these resources fell short in addressing the challenges I faced in my jurisdiction, prompting my decision to pursue advanced studies in the U.S.

My graduate study began at Arizona State University in the master’s program of Fire Service Administration, focusing on strategies and tactics to reduce community risks from firefighters’ perspectives. I was fortunate to complete a one-year internship in the Phoenix Fire Department’s administration building, which enabled me to participate in emergency planning processes (e.g., determining locations for new fire stations and creating EOPs). Subsequent to my master’s program, I pursued a doctoral degree in disaster science and management at the University of Delaware. My dissertation centered on the Incident Command System (ICS), which was completed in 2015. Post-2015, I transitioned into a researcher and university professor role in emergency management, publishing articles on disaster preparedness and response and assisting local governments and private sectors in emergency planning. Additionally, my column in a popular Taiwanese newspaper introducing disaster management concepts and strategies led to numerous reader queries on disaster preparedness and response.

Drawing from these experiences, I have encountered challenges in disaster preparedness and response, identified gaps between planning and implementation, and dealt with the complexities of adapting emergency management systems across countries. Therefore, the questions to be addressed in this research are: what are the things to prepare beforehand? Who should be incorporated in disaster planning processes? And, how do people and organizations prepare for disasters?

In the subsequent sections, this chapter will review research articles on critical emergency management concepts. It will outline the methodologies employed in this chapter, present findings and solutions to the identified challenges, discuss the implications of this research in both academic and practical arenas, and conclude by offering suggestions for improvement and future research directions.

Literature Review

To effectively manage disasters, it is crucial for individuals to comprehend the four phases of emergency management: mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery (Haddow et al., 2011; Lindell et al., 2006; and Phillips et al., 2017). The mitigation phase focuses on reducing natural hazard risks, by completing risk assessments, establishing building codes, and improving urban planning/zoning. Preparedness involves getting ready for potential disastrous impacts by developing disaster plans, conducting training programs, and organizing exercises. In the response phase, actions are taken to address the immediate consequences of disasters, including firefighting, evacuation efforts, and search and rescue operations. The recovery phase begins after life saving measures are addressed, requiring emergency managers to open shelters, relocate the population, provide physical and emotional assistance, and undertake long-term recovery activities like community rebuilding and infrastructure restoration. The four phases are interconnected, with many EM activities often overlapping across different phases (Neal, 1997). For example, analyses, codes, and zoning established in the mitigation phase guide preparedness, and activities before disasters inform responders and citizens on responding to disasters.

Research by Lindell and Perry (2011) demonstrates that pre-disaster preparedness activities affect household responses during disasters. Additionally, Hollywood movies and media play a role in shaping human behaviors in disasters (McEntire, 2022). People’s responses to a disaster trigger short-term recovery activities, such as considerations for relocating evacuees from impacted areas. After short-term recovery efforts, individuals rebuild the community by conducting risk analyses, updating building codes, and redesigning urban zoning. These activities during recovery link back to the mitigation phase. The four EM phases therefore operate as a continuous loop, often emphasizing an integrated process. Strategies for improving hazard and disaster preparedness impact activities related to disaster response and recovery. This entire approach is also known as the Comprehensive Emergency Management (CEM) that was proposed by the National Governor’s Association in 1979 and later became a fundamental principle for managing disasters in the U.S. (Jensen and Kirkpatrick, 2022; NGA, 1979; and Worsely and Beckering, 2007).

To enhance disaster management, Quarantelli (1997) recommends that emergency managers “[r]ecognize correctly the difference between agent-generated and response-generated needs and demands (p.41).” Agent-generated demands are specific to different types of disasters, such as obtaining sandbags to deal with flooding. Consequently, although these agent-generated demands cannot be predicted and prepared beforehand, emergency managers can leverage pre-disaster established networks (e.g., contracts signed beforehand) to secure resources for fulfilling these agent-generated demands. Response-generated demands are universal to any disaster, such as establishing a response system, maintaining communication systems, and providing on-site Emergency Medical Services (EMS). Examples of these demands are those Emergency Support Functions (ESFs) outlined by the U.S. National Response Framework, which are performed by all EM stakeholders in any disaster (DHS, 2019). Thus, emergency managers must plan for agent and response-generate demands and familiarize themselves with all EM stakeholders during the planning processes, thereby enabling quick fulfillment of ESFs during disasters.

The literature above demonstrates that there are many universal response activities between all types and scopes of disasters. Researchers call them response-generated demands and practitioners list them as ESFs. However, researchers’ discussions of these response-generated demands might not be transferred to practical community, and practitioners’ documents of those ESFs might not spur enough academic attention and research projects to develop a holistic view of EM. As a result, this chapter wishes to link my academic training and practical experience to answer the following questions:

-

- What are the things to prepare for before disaster strikes?

- Who should be incorporated in disaster planning processes?

- How do people and organizations prepare for disasters?

Methodology

This research aims to understand the three research questions mentioned above. As a result, qualitative approaches are more suitable for understanding the nature of a social phenomenon and engaging with those nuanced data (Berg and Lune, 2012; Creswell and Poth, 2018; and Patton, 2002). More specifically, I employ a comparative analysis framework to compose this book chapter, encompassing three key elements: 1) a critical analysis of concepts or principles applicable to situations in various contexts, 2) primary research, relevant to the preparedness and response in the U.S. and Taiwan, conducted by me, and 3) cases or comparative studies based on primary and secondary resources.

The comparative analysis framework is widely used to understand how different countries handle similar issues (e.g., Ai, 2023; Dederer and Frenken, 2022; Pollitt and Bouckaert, 2011; and Raha and Raju, 2021). To apply this framework to a research project, it is imperative to define the unit of analysis (e.g., what is compared and analyzed). In this research, I compare and analyze disaster preparedness and response challenges and strategies between Taiwan and the U.S. In the cases related to Taiwanese disaster preparedness and response, all discussions are based on:

-

- my previous research projects, which included peer-reviewed articles, governmental documents, media reports, and/or interviews with the disaster responders (for example, see Chang, 2021, for data sources and quality),

- discussions with emergency management stakeholders in Taiwan,

- my practical experience,

- information that can be accessed publicly (e.g., a firefighting magazine, Fire Safety Monthly, published by the National Fire Agency in Taiwan).

The U.S. cases and discussions are derived from: 1) peer-reviewed articles, and 2) federal documents (e.g., the Homeland Security Exercise Evaluation Program). Since those research articles have been cited and tested many times, linking my ideas and suggestions to well-cited research articles and established U.S. federal documents adds weight and value to this chapter.

I realize the selection of cases, literature, and research projects might inevitably create some bias in this research, so I will discuss limitations of the present research in the following section.

Limitations

Given that my practical experience, academic training, and other EM-relevant understandings are centered in Taiwan and the U.S., there is a limitation to applying these discussions and solutions to other countries. Additionally, I acknowledge that more perspectives and discussions are relevant to disaster recovery and risk mitigation (e.g., global warming and resilience). Since this chapter focuses solely on disaster preparedness and response, readers should anticipate that several methods and strategies to handle disasters and reduce their impacts are not covered.

Findings and Solutions

Based on my practical experience and academic training, I believe using a broad view of EM is critical for disaster preparedness and response. More specifically, EM strategies and policies should be developed with personnel of various backgrounds, which cover all phases of EM, so professionals are able to use multiple tools and strategies to manage disasters. I will provide case studies and academic citations below to illustrate my viewpoints.

Finding 1: The Importance of Using a Broad View of Preparedness and Response

In adhering to the concepts of the CEM, any changes in disaster response should be initiated in the preparedness phase, influencing subsequent phases of EM. For instance, if responders wish to utilize different strategies in disaster response, emergency managers need to update disaster plans, training programs, and exercise guides. This necessitates modifications in disaster recovery activities aligned with these plans and subsequent response activities. Therefore, when preparing for and responding to disasters, people need to plan for changes and ways of implementation in the four phases of EM. Two cases demonstrate the importance of using the lens of CEM to consider preparedness and respond to relevant challenges.

Case 1-Introducing ICS to Taiwan

The Taiwanese government attempted to introduce ICS to orchestrate the on-site response activities in the 2000s. Few scholars began with the translation (from English to Chinese) of all ICS documents and forms. However, despite initial efforts, the system is not widely used during disasters in Taiwan. For example, a report made in 2009 by two Taiwanese disaster response scholars assigned every ICS position to officials from a local government. In their report, all ICS positions should be open and filled when the Incident Commander (IC) arrives at the scene (Deng and Shen, 2009). To respond to an earthquake in southern Taiwan in 2016, the IC claimed that he had utilized the ICS to coordinate the on-site activities, but the ICS organizational chart he drew only included firefighters (Li, 2016). Consequently, two retired Taiwanese fire chiefs stated that this system does not consider the full range of responders in Taiwan. Thus, this system cannot be applied to coordinate response activities in Taiwan (Zhao and Huang, 2009).

A possible way to introduce the ICS to Taiwan is to look at the broader picture. Again, since all phases of EM would influence each other, to introduce a disaster response system, people need to use the same system or similar ideas to prepare for disasters. For example, suppose one only sees the response phase and those scenarios/problems generated in response. In that case, they might be unable to promote this response system to those civilian agencies and organizations. As a result, to make the ICS work, scholars suggest pre-conditions (Bigley and Roberts, 2001; Buck, Trainor, and Aguirre, 2006; Moynihan, 2007; and Neal and Phillips, 1995), such as planning for disasters using the ICS framework to build relationships and trust between all EM stakeholders (Chang and Trainor, 2018).

Case 2-EM Suggestions for a Private Company

A second example demonstrates the importance of looking at those preparedness and response challenges from the CEM perspective. A reader of my newspaper column, serving as the Director of Security for a popular department store in Taiwan, received conflicting strategies from scholars and experts to improve EM capabilities. These scholars and experts gave him dichotomous strategies to mitigate risks. For instance, a researcher from a civil engineering background suggested he raise the height of the gates on all entrances so they could block water during hurricanes and flash floods. Another scholar with fire engineering and egress design backgrounds wished him to lower the gates so people could evacuate quickly and smoothly from the department store.

A possible solution for this paradox is to evaluate these suggestions in the four phases of EM. Finding alternatives to reach the goals is essential. For instance, directing water to neighboring ponds and lakes can reduce flooding risks. Therefore, the company does not need to raise the gates on the major entrances. Establishing more emergency exits can aid in smooth evacuation by lowering the gates. Therefore, disaster preparedness requires a broader view and a longer time frame to consider strategies and tactics for risk reduction. Without planning and preparedness, responders may focus only on response scenarios, neglecting options during the other three phases of EM.

Finding 2: What to Prepare for Disasters

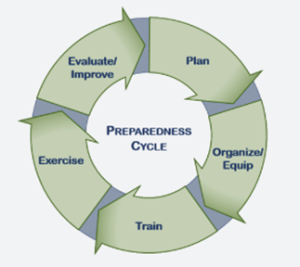

Disaster preparedness includes three elements: planning, training, and exercising. It is imperative to link these three preparedness elements together. More specifically, FEMA’s Preparedness Cycle (FEMA, 2010) underscores the significance of utilizing disaster plans to inform EM training programs, orchestrating disaster exercises to assess and enhance their effectiveness, and integrating feedback from exercises to revise and improve disaster plans (See Figure 1 below). The following two cases illustrate the importance of linking plans, training, and exercises.

Case 3-The Gap Between Planning and Implementation

To understand how EM stakeholders prepare for earthquakes in Oklahoma, three researchers and I conducted qualitative interviews in 2017. A senior emergency manager in Oklahoma told us, “We have state building codes but do not have people to enforce these codes” (For detailed information on the completion of this research and the IRB approval letter, refer to Chang et al., 2018). In this scenario, a disconnect arises as new building codes fail to align with disaster plans (which involve hiring personnel for enforcement), hindering the provision of relevant training programs to law enforcement personnel. Consequently, only a few buildings in Oklahoma were constructed and designed to withstand severe earthquakes.

A similar challenge was witnessed in Taiwan. Drawing from my experience planning the longest tunnel in Taiwan, regular meetings with the Minister of Transportation were imperative to secure the tunnel. My estimation revealed that the budget for establishing fire stations at both ends of the tunnel and equipping firefighters to respond to emergencies (e.g., HAZMAT, fire, and car accidents) exceeded the budget allocated for tunnel construction. Once again, the realization that planning is merely the initial step in disaster preparedness underscores the fact that procurement of apparatus for responders, promotion of training, and completion of exercises demand significant time and financial investment. Again, to successfully respond to disasters, emergency managers develop plans and then organize training courses and exercises to evaluate and update these plans. As a result, when budgeting for disaster plans, one has to consider those expenses and resources associated to training and exercises.

Case 4-The Gap Between Training and Exercises

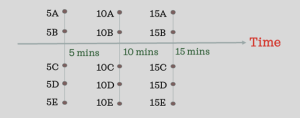

Another unique problem also relates to training and exercises. In my role as a fire officer, I organized disaster exercises in my jurisdiction. Traditional disaster exercises tend to emphasize predefined disaster scenarios, with participants assigned specific actions. Unfortunately, this approach limits responders’ ability to think critically and develop alternative strategies and tactics for disaster response, diminishing their ability to handle unexpected disastrous situations. Recognizing that disasters unfold over time and that people possess several options and strategies to fulfill specific missions in critical moments, we can envision a more dynamic and effective approach. When a disaster unfolds over time (the X axis on Figure 2), for instance, emergency managers might have various options (e.g., firefighting, search and rescue, and relocation) in different time slots (the Y axis on Figure 2). If we assume emergency managers can select 5 EM strategies in the moments of 5, 10, and 15 minutes, we will see that there are 125 (53) combinations (possibilities) of disaster response activities as illustrated below:

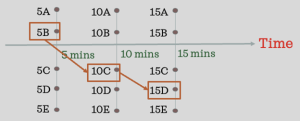

However, traditional disaster exercises in Taiwan typically assign a specific role and mission to each participant and thus the organizers had predetermined disaster response activities in each time slot (e.g., a particular organization must complete specific tasks in a given time). Consequently, these exercises have limited the range of disaster response possibilities (in this hypothetical example, from 125 to 1) and therefore they limited participants’ abilities to consider all possible response activities in a given time:

A potential solution to bridge this gap is to invite all EM stakeholders to discuss strategies and possible response activities beforehand. These discussions, based on established disaster plans and training programs, aim to mitigate risks before organizing full-scale exercises. Participants would begin with simple situations involving merely a few organizations and then expand to complex disastrous scenarios. This approach ensures that EM stakeholders focus not only on final stages or worst-case scenarios but also on preparing for response-generated demands, such as ESFs. This concept echoes the U.S. Homeland Security Exercise Evaluation Program (HSEEP), which recommends discussion-based exercises to build capabilities for organizing full-scale exercises (FEMA, 2020).

Following this train of thought, disaster researchers posit that every event develops from a minor emergency (handled by 1-2 agencies) to a disaster (requiring all departments and resources of a city or country) (Quarantelli, 1996). If a disaster expands to a national or international scale, it becomes a catastrophe (Quarantelli, 2005). As a result, disaster response and recovery should be viewed as a spectrum, addressing disasters on small to large scales and recovering accordingly, not merely in particular moments.

A reader of my newspaper column who worked for the Taipei City government once asked, “If a missile strikes a skyscraper in Taipei City, how can we respond to this war-time scenario?” Similarly, while developing an Exercise Handbook for Taiwanese Critical Infrastructures, an official from the National Office of Homeland Security questioned: “Do we need to add war-time scenarios to this handbook?” As mentioned earlier, disaster response and recovery should be seen as a spectrum, requiring preparation for a series of pre-strike conditions rather than specific moments. Before a missile strikes, warnings can be issued, people can be evacuated, and streets in Taipei City can be blocked, making it easier for responders to handle potential mass fatalities. Furthermore, diplomatic negotiations and other non-military measures can be employed before a country launches a missile or initiates a war, allowing people enough time to react. Realizing this, emergency managers would not panic about all possible outcomes or those “worst case scenarios.” Even after missile strikes, responders still need to take similar actions (e.g., those ESFs) as they respond to natural hazards. Consequently, it is imperative for disaster responders to focus on and prepare for those response-generated demands and build trust and relationships between all EM stakeholders. Therefore, they can quickly fulfill those agent-generated demands during disasters.

In summary, developing plans, offering training programs, and organizing exercises are three critical components of disaster preparedness. These measures, in turn, require that emergency managers incorporate more EM stakeholders into planning to build networks to meet agent-generated demands during disasters. In the next section, I will discuss who should be involved in preparing for disasters.

Finding 3: Who Should Be Involved in Preparing for Disasters

Taiwanese emergency managers have historically focused heavily on response and prepared for response (Chang, 2017; Tso and McEntire, 2011). This response-oriented preparedness style may neglect those tools and strategies for mitigating hazards and recovering from disasters. Consequently, emergency managers with this mindset are too reactive; they are not considering other actions to reduce the impact of disasters or rebound when they occur. The following case demonstrates the drawbacks of using a response-oriented EM system.

Case 5-Fire-centric Disaster Preparedness in Taiwan

The Taiwanese government relies on a fire and response-centric disaster preparedness and response system, delegating many disaster management missions to Taiwan’s National Fire Agency (NFA) and local fire departments. As a result, when responding to disasters, responders focus heavily on these familiar roles and frequently have difficulties cooperating with civilian organizations that are in charge of missions outside of response (see Chang et al., 2021, for more discussions on the challenges of using a fire and response-centric EM system in Taiwan).

Fire and police departments (which are often in charge of developing EOPs) might have challenges when coordinating with civilian departments due to different organizations and organizational cultures (Lindell and Perry, 2007). In addition, firefighters and emergency managers also receive different types of training and levels of education. Analyzing the significant textbooks on firefighting and emergency management in the U.S., I found that firefighters might need more training and education in risk mitigation and disaster recovery to become effective emergency managers (Chang and Neal, 2019). As a result, fire departments might not be an optimal organization to oversee the four phases of EM in a jurisdiction.

To address the question of who should be involved in disaster preparedness, I suggest including as many individuals from diverse backgrounds as possible. Incorporating diverse EM stakeholders (such as personnel from civilian departments and organizations, non-governmental organizations, and volunteer groups) in disaster preparedness will broaden the knowledge base for decision-making through lateral thinking and perspective, thus increasing the capability to handle events with profound uncertainty, such as disasters (Kasperson, 2009; Tironi and Manriquez, 2019). The uncertainties of disasters will be further discussed in the next section.

Finding 4: How You Should Prepare for Disasters

When planning for disasters, one must acknowledge that uncertainties persist, regardless of the efforts invested. For example, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) predicts a high likelihood of a mega earthquake (magnitude above 6.7) in the San Francisco Bay Area within the next 30 years. However, the USGS scientists, after they spent enormous time and efforts on establishing prediction models and conducting investigations, still cannot precisely predict when the earthquake might occur or the exact scale of the event (USGS, 2015). Similarly, Taiwanese responders had practiced several times on searching and rescuing of passengers when an airplane crashed on land annually. Still, when an aircraft crashed into a river from the border of two cities, they spent much time finding innovative ways to complete their missions (Chang et al., 2021).

Therefore, no matter how hard we try, there are still many moving parts in disaster response. To address these moving parts (or the uncertainties of disasters), emergency managers need to focus on disaster response functions (or the response-generated demands mentioned previously) instead of scenarios. Emphasizing disaster response functions allows the establishment of standards, training programs, and drills on fundamental but imperative activities that apply to any disaster. Excessive attention to scenarios leads emergency managers and responders to endless details (e.g., differences between an earthquake response with and without rain) and confusion (e.g., recommendations for one scenario or country may not apply to another).

Additionally, emergency managers and responders must recognize that standardized procedures (e.g., Standard Operations Procedures, SOPs) may not be suitable for every disaster. In situations of high uncertainty, emergency managers must allow responders to be more agile on-site, improvising to fulfill agent-generated demands (see Penta et al., 2021, pp.8-9, for more examples illustrating the importance of improvisation on response). Consequently, disaster response should incorporate elements of both discipline and agility. More disciplined principles can be applied to disaster response in small-scale disasters, but as disasters grow, emergency managers must adopt more agility to handle uncertain situations (Bigley and Roberts, 2001; Chang and Trainor, 2020; and Harrald, 2006).

In summary, five major findings from above discussions are:

-

- Understand the concept of CEM and then balance policies and strategies in all phases of EM,

- Realize disasters unfold by time, and thus use a continuing view to plan for and respond to disasters,

- Allow responders to discuss and think of possible response strategies beforehand to build their abilities of improvisation,

- Incorporate EM stakeholders of various backgrounds into the disaster planning processes, and

- Prepare for response-generated demands and allow responders to improvise on the ground.

Discussion

Based on the previous discussions, three major lessons were learned from my previous experience and research. They are: 1) emergency managers need to use broader perspectives to plan for disasters; 2) emergency managers need to link plans, training, and exercises to form the preparedness cycle; and 3) there is a need to bridge gaps between practitioners and researchers (e.g., lesson learned from practical communities should be transferred to academic research projects and vice versa). I will discuss them in the following sections.

Using Broader Perspectives to Plan for Disasters

Since no one can understand every perspective and type of disaster, it is imperative to collaborate with people from various backgrounds to reduce impacts of hazards and therefore facilitate disaster preparedness. By doing this, emergency managers need to think outside the response and preparedness boxes and realize the tools and benefits of mitigation and recovery.

For example, the city of Scottsdale in Arizona passed an ordinance regulating all new residential buildings to install fire sprinkler systems in 1986. Consequently, residential cases dropped sharply, and eventually, the city government could contract the fire service to private companies until 2005 (Richard, 2008). By employing a tool to mitigate the risk of residential fires, the city government reached a win-win situation; it reduced the deaths from residential fires and saved budgets from establishing and maintaining fire and EMS stations. As shown in the Taiwanese case discussed previously (case 5), if emergency managers focus only on response and preparedness, they might be unable to develop this risk reduction strategy.

Also, as those ESFs are relevant to different agencies and organizations, emergency managers must work with EM stakeholders to better prepare for disasters. The disaster planning processes are more important than the products (plans) because they can strengthen pre-disaster networks and thus facilitate disaster response. For example, see Monyhan’s case study on the 9/11 D.C. response (Moynihan, 2007).

Linking Plan, Training, and Exercise

Emergency managers should link plans, training, and exercises to form the FEMA disaster preparedness cycle (FEMA, 2010) and advance these three components. More specifically, emergency managers, based on the knowledge they can obtain (e.g., codes, regulations, and results of risk analyses), should develop disaster plans, provide training programs to responders, and organize various types of disaster exercises to evaluate the effectiveness of plans and training programs.

Linking these three elements of preparedness is imperative. First, the linkage ensures everyone in this cycle understands the codes, regulations, and risk analysis results. For instance, when we interviewed Hawaii EM stakeholders on preparing for sea level-relevant disasters, many believed the Hawaii Department of Transportation in the Harbor area (Harbor division) would be responsible for several disaster response challenges researchers mentioned. However, when we interviewed an official from the DOT Harbor division, they clarified that their organization was only in charge of roads and critical infrastructures inside the harbor, and the roads connected to the harbor are managed by state or local governments (See Shen et al., 2022, for details of this research and the IRB approval letter). To understand how the Oklahoma State and City government (OKC) prepared for earthquakes in 2017, many EM stakeholders we interviewed believed that the Department of Planning in the OKC already had some plans to reduce the risks and impacts of large-scale earthquakes. However, an official from the OKC planning department admitted that his/her organization has not developed these risk reduction plans yet (Chang, et al., 2018).

Similarly, when I organized a full-scale disaster exercise in Taiwan, I tasked the Department of Transportation (DOT) in my jurisdiction with providing two buses to assist in evacuating those affected by the disaster. A representative from the DOT told me that while they are responsible for administrating transportation-related affairs, they do not possess the skills to operate buses. In this situation, the most crucial aspect would be to revise the disaster plans, clearly outlining the responsibilities of all EM organizations, and subsequently implementing training programs tailored to each organization’s role and missions. It is imperative that the annual disaster exercises align seamlessly with plans and training programs, ensuring that EM stakeholders comprehend the tasks they are expected to undertake both before and during disasters (Sutton and Tierney, 2006). As President Dwight D. Eisenhower once famously said: “I tell this story to illustrate the truth of the statement I heard long ago in the Army: ‘Plans are worthless, but planning is everything’” (Eisenhower Library, 2023). Emergency managers are suggested to use those planning processes to assist all EM stakeholders in understanding the current situations and regulations.

Following this line of thought, exercise programs should begin with discussion-based exercises before moving to more complex operation-based exercises. Participants in these exercises should ground their discussions in established disaster plans, the training they have received, and their expertise to provide solutions in disastrous situations.

For instance, the decision to receive international aid involves complex considerations relevant to national security (e.g., accepting assistance from a hostile country), international politics (e.g., accepting aid from every country or only those with which we agree), and liabilities (e.g., validating the credentials and activities of experts) (See Sylves, 2015, pp.226-229, for challenges and dilemmas faced by the U.S. Federal Government in receiving international aid during Hurricane Katrina). As a result, responders may need to leverage discussion-based exercises to explore viable solutions for these complex situations. As Figure 2 shows above, Taiwanese emergency managers must explore many options during discussion-based activities. Otherwise, responders may find themselves restricted to specific response actions, hindering their agility in disaster response.

Bridging the Gaps Between Disaster Researchers and Practitioners

Finally, it is critical to establish connections between researchers and practitioners to enhance disaster preparedness and response. On the one hand, there is a need to create more accessible and user-friendly environments for practitioners to access the latest disaster research. Many practitioners face difficulties accessing peer-reviewed research articles due to their organizations lacking subscriptions to EM journals. This issue might be improved by cooperating with local universities and access to their library databases, contact with authors to obtain copies of their research manuscripts, and search for those open access journals and websites to read full-text of research papers (e.g., the Google Scholar and the Research Gate). On the other hand, researchers must acknowledge how EM policies and strategies are implemented on the ground. For instance, researchers and practitioners often hold different perspectives and evaluations of ICS. Researchers focusing on large-scale disasters may reject the system, believing it cannot handle complex situations. Conversely, ICS users appreciate the system’s effectiveness in responding to small-scale emergencies, highlighting its value in facilitating on-site coordination (Chang, 2017). Since some results from academic research also match the experience from practitioners (e.g., the response-generated demands and the ESFs are universal to all types of disasters), researchers might need to participate in more disastrous response activities to obtain the first-hand information and research data (see Kendra and Wachtendorf, 2003, for instance), analyze national policies and guidelines to retrieve the insights and experience from practitioners (see Chang and Trainor, 2020, for example), and then demonstrate both voices from academic and practical communities toward a same topic to help readers realizing various perspectives of EM issues (see Trainor and Subbio, 2014, for example).

Conclusion

This chapter utilizes examples from my professional experience and research projects to illustrate the challenges of disaster preparedness and response. Given the critical nature of preparing for and responding to disasters for governmental agencies and private sectors, it is essential to review the typical difficulties of planning for and handling disasters.

This chapter specifically advocates for responders and emergency managers to adopt a broader view, utilizing the CEM framework to manage disasters. Recognizing the importance of all four EM phases enables using various tools to mitigate risks. It is emphasized that linking disaster plans, training programs, and exercises is crucial. Following the FEMA preparedness cycle, these three elements facilitate each other, with disaster plans guiding the development of training programs. Emergency managers then organize various disaster exercises to evaluate the effectiveness of plans and training programs, advancing the preparedness cycle. Finally, collaboration between researchers and practitioners is vital for designing and implementing effective disaster policies and systems. For example, the ICS research can benefit from linking theories and practice, and topics like the design and operation of the Emergency Operations Centers offer collaborative exploration opportunities for both sides (See Loebach et al., 2023, for example).

Building upon the challenges discussed in previous sections, future EM research, and discussions may focus on:

-

- The difficulties of implementing EM policies (e.g., utilizing the HSEEP to organize types of exercises).

- The applications of EM systems from one country to another (international EM).

- Applying disaster research to facilitate practical work (e.g., using methods for coping with highly uncertain events to respond to complex, large-scale disasters).

References

Ai, H. (2023). Protecting societal interests in corporate takeovers : a comparative analysis of the regulatory framework in the U.K., Germany and China. Singapore: Springer.

Alexander, D. (2000). Confronting catastrophe. New York, U.S.A: Oxford University Press.

Berg, B., and Lune, H. (2012). Qualitative research methods for the social scientists. New Jersey, USA: Pearson Education, Inc.

Bigley, G., and Roberts, K. (2001). The incident command system: High-reliability organizing for complex and volatile task environments. The Academy of Management Journal, 44, 1281-1299.

Buck, D., Trainor, J., and Aguirre, B. (2006). A critical evaluation of the incident command system and NIMS. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, 3(3), 1-27.

Chang, H. (2017). A literature review and analysis of the incident command system. International Journal of Emergency Management, 13(1), 50-67.

Chang, R. and. Neal, D. (2019). Promotion or transition: From fire officer to emergency manager. Journal of Emergency Management, 17(2), 101-110.

Chang, R. and. Trainor, J. (2018). Pre-disaster established trust and relationships: Two major factors influencing the effectiveness of implementing the ICS. Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, 15(4) doi:10.1515/jhsem-2017-0050

Chang, R. and. Trainor, J. (2020). Balancing mechanistic and organic design elements: The design and implementation of the incident command system (ICS). International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 38(3), 241-267.

Chang, R., Greer, A., Murphy, H., Wu, H-C, and Melton, S. (2018). Maintaining the status quo: Understanding local use of resilience strategies to address earthquake risk in Oklahoma. Local Government Studies, , 433-452.

Chang, R., Tso, Y-E., Lin, C-H., and Kwesell, A. (2021). Challenges to the fire service-centric emergency management system. Natural Hazards Review, 23(1) doi: https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000523

Creswell, J., and Poth, C. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Dederer, H.-G., & Frenken, G. (Eds.). (2022). Regulation of genome editing in human iPS cells : a comparative legal analysis of national regulatory frameworks for iPSC-based cell/gene therapies. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Deng, T. and S., T. (2009). A research on applying ICS functional divisions on local EOCs and on-site response activities. [ICS功能編組應用於區災害應變中心及災害現場搶救作業之研究]. Retrieved from https://www.grb.gov.tw/search/planDetail?id=2053765 (Accessed on 01/04/2024).

Department of Homeland Security. (2019). National response framework. (). Retrieved from https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-04/NRF_FINALApproved_2011028.pdf (Accessed on 01/04/2024).

Dwight D. Eisenhower: Presidential Library, Museum $ Boyhood Home (Eisenhower Library). (2023). Quotes. Retrieved from https://www.eisenhowerlibrary.gov/eisenhowers/quotes (Accessed on 01/04/2024).

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2010). Developing and maintaining emergency operations plans. Retrieved from https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-05/CPG_101_V2_30NOV2010_FINAL_508.pdf (Accessed on 01/04/2024).

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2020). Homeland security exercise and evaluation program (HSEEP). Retrieved from https://www.fema.gov/emergency-managers/national-preparedness/exercises/hseep (Accessed on 01/04/2024).

Haddow, G., Bullock, J., and Coppola, D. (2011). Introduction to emergency management (4th ed.). USA: Elsevier, Inc.

Harrald, J. (2006). Agility and discipline: Critical success factors for disaster response. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, (604), 256-272.

Jensen, J. and Kirkpatrick., S. (2022). Local emergency management and comprehensive emergency management (CEM): A discussion prompted by interviews with chief resilience officers. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 79 doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103136

Kasperson, R. (2009). Coping with deep uncertainty: Challenges for environmental assessment and decision-making. In G. &. S. Bammer M. (Ed.), Uncertainty and risk: Multidisciplinary perspectives (pp. 337-348). USA: Earthscan Co.

Kendra, J. M. and Wachtendorf, T. (2003). Reconsidering convergence and converger legitimacy in response to the world trade center disaster. In L. Clarke (Ed.), Terrorism and Disaster: New Threats, New Ideas (Research in Social Problems and Public Policy, vol. 11) (pp. 97-122) Emerald Group Publishing Limited. doi:10.1016/S0196-1152(03)11007-1

Li, M. (2016). Record of the February 6 earthquake rescue effort by Tainan fire department. [台南市政府消防局0206震災救援紀實] Fire Safety Monthly, , 17-28.

Lindell, M. K. and Perry, R. W. (2011). The protective action decision model: Theoretical modifications and additional evidence.32(4), 616-632. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01647.x

Lindell, M., Prater, C. and Perry, R. (2006). Fundamentals of emergency management. Retrieved from https://training.fema.gov/hiedu/aemrc/booksdownload/fem/ (Accessed on 01/04/2024).

Lindell, M., and Perry, R. (2007). Planning and preparedness. In W. &. T. Waugh K. (Ed.), Emergency management: Principles and practice for local government (2nd ed., pp. pp.113-142). U.S.A: ICMA Press.

Loebach, P., Chavez, J., De Souza, A., and Caciola, C. (2023). The State of Emergency Operations Centers in Colorado. Natural Hazards Center Quick Response Research Report Series, 362. Boulder, CO: Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado Boulder. Available at: https://hazards.colorado.edu/quick-response-report/the-state-of-emergency-operations-centers-in-colorado (Accessed on 01/23/2024).

McEntire, D. A. (2022). Disaster response and recovery: Strategies and tactics for resilience. (3rd ed.). U.S.A: Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Moynihan, D. (2007). From forest fires to hurricane Katrina: Case studies of Incident Command System. IBM Center for The Business of Government.

National Governors’ Association. (1979). Comprehensive emergency management: A governor’s guide. Washington D.C.: NGA.

Neal, D. (1997). Reconsidering the phases of disaster. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters, 15(2), 239-264.

Neal, D. and. Phillips, B. (1995). Effective emergency management: Reconsidering the bureaucratic approach. Disasters, 19(4), 327-337.

Patton, M. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd ed.). CA, U.S.A: Sage Publications, Inc.

Penta, S., Kendra, J., Marlowe, V., and Gill, K. (2021). A disaster by any other name? COVID-19 and support for an all-hazards approach. Risk Hazards Crisis Public Policy, 1-26.

Phillips, B., Neal, D., and Webb, G. (2017). Introduction to emergency management (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Pollitt, C., and Bouckaert, G. (2011). Public management reform a comparative analysis : new public management, governance, and the neo-Weberian state (3rd ed.). Oxford ; Oxford University Press.

Quarantelli, E. L. (1996). Just as a disaster is not simply a big accident, so a catastrophe is not just a bigger disaster. The Journal of the American Society of Professional Emergency Planners, 68-71.

Quarantelli, E. L. (1997). Ten criteria for evaluating the management of community disasters. Disasters, 21(1), 39-56.

Quarantelli, E. L. (2005). Catastrophes are different from disasters: Some implications for crisis planning and managing drawn from Katrina. Retrieved from https://unitedsikhs.org/katrina/catastrophes_are_different_from_disasters.pdf (Assessed on 01/22/2024).

Raha, U. K., and Raju K.D. (2021). Submarine cables protection and regulations : a comparative analysis and model framework. Singapore: Springer.

Richard, U. (2008). Residential fire sprinkler reliability in homes older than 20 years old in Scottsdale, AZ. Emmitsburg, MD: National Fire Academy.

Shen, S., Chang, R., Kim, K., and Julian, M. (2022). Challenges to maintaining disaster relief supply chains in island communities: Disaster preparedness and response in Honolulu, Hawai’i. Natural Hazards, 114, 1829-1855. doi:10.1007/s11069-022-05449-x

Sutton, J., and Tierney, K. (2006). Disaster preparedness: Concepts, guidance, and research. Colorado, CO: Institute of Behavioral Science, University of Colorado. Retrieved from https://www.bencana-kesehatan.net/arsip/images/referensi/april/Disaster%20Preparedness%20Concepts_Jurnal.pdf (Accessed on 01/24/2024).

Sylves, R. (2015). Disaster policy and politics (2nd ed.). Washington DC: CQ Press.

Tironi, M. and Manriquez, T. (2019). Lateral knowledge: Shifting expertise for disaster management in Chile. Disasters, 43(2), 372-389.

Trainor, J. E., & Subbio, T. (Eds.). (2014). Critical issues in disaster science and management: A dialogue between researchers and practitioners. Emmitsburg, MD: FEMA Higher Education Project. Retrieved from http://udspace.udel.edu/handle/19716/13418 (Accessed on 05/22/2024).

Tso, Y. and McEntire., D. A. (2011). Chapter 26: Emergency management in Taiwan: Learning from past and current experiences. In D. A. McEntire (Ed.), Comparative emergency management book (pp. 1-21). Emmitsburg, MD: Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20230603172359/https://training.fema.gov/HiEdu/downloads/CompEmMgmtBookProject/Comparative%20EM%20Book%20-%20EM%20in%20Taiwan.pdf (Accessed on 01/08/2024).

United States Geological Survey (2015). What is the probability that an earthquake will occur in the San Francisco Bay area? Retrieved from https://www.usgs.gov/faqs/what-probability-earthquake-will-occur-los-angeles-area-san-francisco-bay-area#:~:text=San%20Francisco%20Bay%20area%3A,an%20earthquake%20measuring%20magnitude%207.5 (Accessed on 01/04/2024).

Worsely, T. L. and Beckering, D. (2007). A comprehensive approach to emergency planning. College and University, 82(4), 3-6. Retrieved from https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/comprehensive-approach-emergency-planning/docview/225612405/se-2 (Accessed on 01/05/2024).

Zhao, G. and H., D. (2009). Firefighting tactics – fire command sizing-up and simulation. [火場指揮狀況判斷與推演] Taiwan: Ding Mao Publication.