21 The Challenges to a Modern Approach to Leadership, Management, Critical Thinking, and Decision Making Within an Emergency Management Environment

Glenn Jones ESM CEM® and Christopher J Ainsworth MBA CEM®

Authors

Glenn A. Jones ESM, CEM® BAdmin Lead UNEAdv Dip PS (EM) Dip PS (EM), Dip VET, Dip TAE TDD, Dip QA2

Christopher Ainsworth, MBA, CEM®

Keywords

leadership; management; critical thinking; decision making; ethics

Abstract

Leadership and management are mutually reliant. Leaders require management systems and practices that facilitate ethical decision-making within a culture of interconnected individuals who experience inclusivity, have their competence recognized, and are empowered in their positions. Meanwhile, ethics and decision-making exert significant pressure on emergency management leaders for several reasons, such as building trust and confidence, fairness in the allocation of resources, and prevention of moral injury. Therefore, developing and validating ethical frameworks to support decision-making in disaster management practice is essential.

The rapid application of technology, excessive data, climate change, and alterations in generational attitudes and beliefs exert significant pressure on emergency management organizations to adapt.

This chapter discusses the challenges and factors to consider for change and the importance of consistently leading, engaging, and empowering individuals to be linked and engaged in emergency management procedures, especially in emergencies or disasters. It incorporates seminal and cutting-edge research from academic studies, journals, courses, and other relevant sources. It seeks to provoke contemplation and provide insight into alternate approaches to existing methodologies. The purpose is to provide possibilities for transformation grounded in rigorous research and widely acknowledged methodologies. The chapter’s findings reveal commonalities in critical thinking and decision-making that could serve as a foundation for a novel approach or ongoing enhancement, particularly in how ethical intent can guarantee that the analysis and decisions align with ethical and moral standards.

Introduction

Contemporary leaders in emergency management need to adjust to a technologically evolving environment, substantial climate change affecting communities, and a generation with a distinct mindset when meeting workplace expectations, compliance, and actions that deviate from current management practices and leadership styles. This question and these issues also affect management strategies that are still deeply rooted in the three primary streams or pillars: system (i.e., inter-related and inter-dependent), contingency (i.e., inter-actions and inter-relationships internal and external of the organization), and quantitative (i.e., measurable). In the context of a digital environment and geographically scattered workforce and assets, are these fundamental principles still relevant, or is there a necessity to adopt a novel management approach? Do they effectively engage and communicate with the younger generation of employees, stakeholders, and volunteers from an emergency management standpoint? These are important inquiries that must be considered.

Both leadership and management utilize critical thinking and decision-making skills. To effectively address the rapidly changing and complex challenges of the 21st century, organizations must adopt ethically driven and empowering policies and procedures that encourage critical thinking, discretion, and flexibility in decision-making.

Leadership, management, critical thinking, and decision-making are interconnected and essential components of a comprehensive approach. Catherine Rezak, a co-founder of Paradigm Learning Inc. and a contributor to the International Institute of Directors and Managers Expert Talk Panel (Hester, 2021), argues that leaders should actively manage their critical thinking processes, assess them, and subsequently act upon them. Rezak further asserts that numerous recent studies and surveys have identified critical thinking as the foremost prerequisite for effective leadership in the 21st century (Hester, 2021).

Amidst a period of rapid and significant changes encompassing economic, technological and geopolitical aspects, leaders in the contemporary world must excel in an atmosphere characterized by uncertainty. This necessitates the ability to think critically and make daring decisions. Mary Ludden, an assistant teaching professor of Project Management at Northeastern College of Professional Studies, Boston, U.S., points out that this principle applies to both leadership and management, and reiterates that all leadership positions in emergency management involve managerial responsibilities (Doyle, 2019).

Ethics also plays a crucial role in emergency and disaster management. Ethical considerations guide the decision-making process, ensuring that it is fair, respectful, and beneficial to all involved. The ethical development of decision-makers during emergencies and disasters carries significant ramifications. Irrespective of the implementation of emergent technologies aimed at bolstering institutional resilience, human resource management or emergency preparedness, pivotal decisions will inevitably have to be made during critical periods, frequently without the assistance or sanctions of senior management. Understanding the factors contributing to a lack of ethical maturity could facilitate additional research to determine how to improve it, possibly by requiring or instituting higher levels of education for emergency managers or through training initiatives. In light of the increasingly complex and cooperative nature of future calamities that emergency managers will inevitably encounter, all individuals must uphold ethical standards to optimize their effectiveness.

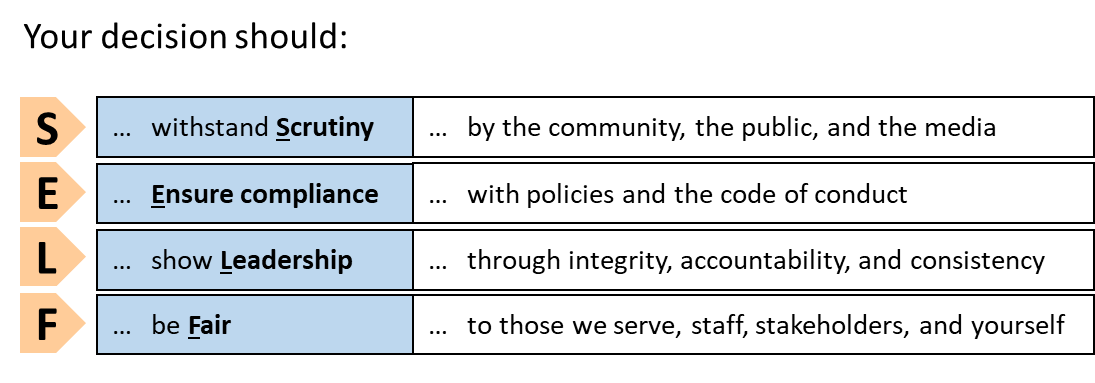

A guide to ethical conduct can be found in the U.S. FEMA “SELF” standard (FEMA, 2023):

Literature Review

The literature review identifies the challenges and presents options or solutions that organizations, leaders, and managers can adopt to meet their circumstances. The literature review for this paper is detailed in 2 sections: 1). Foundations for modern leadership and the expanding demand for interrelated management skills, and 2). Critical thinking and decision-making. Each will be discussed in turn.

Principles of Contemporary Leadership

According to the 2021 Global Culture Report (O.C. Tanner Institute, 2021), a survey of 40,000 employees and leaders in 20 countries revealed that a mere 17% exhibited the mindset and behaviors characteristic of a contemporary leader, closely linked to organizational culture. This raises an important question: What defines a modern leader?

In his Forbes piece, Stuart (2021) asserts that contemporary leadership encompasses the dissemination of knowledge, fostering a heightened level of trust, and cultivating a sense of inclusion and belonging. Senior leadership in large American firms is transitioning from being the primary decision-maker to the manager of information systems. Leadership is primarily determined by the influence of the overarching objectives, as well as the development of the skills and preservation of the independence of several decision-makers (Greenleaf et al., 2002).

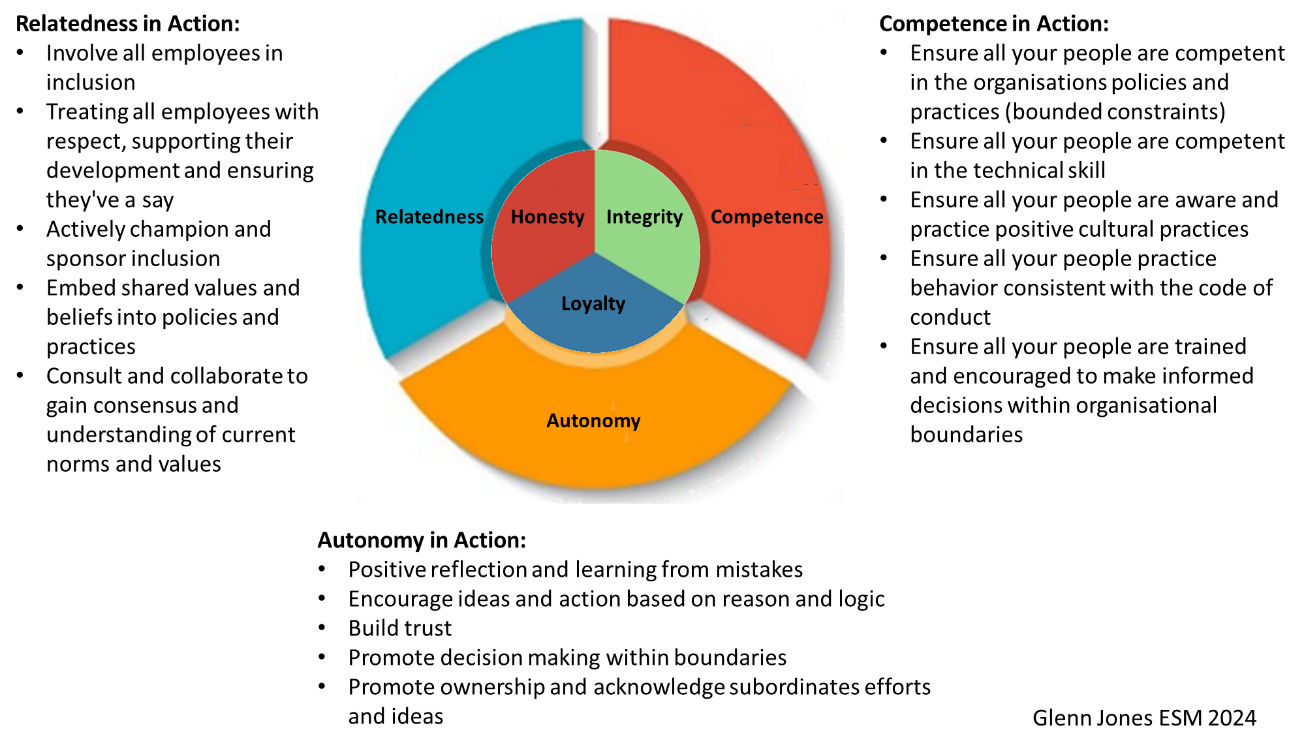

The shift is consistent with Self Determination Theory (SDT) (see Ryan & Deci, 2017), which posits that leaders in practice strive to fulfill three fundamental psychological needs: autonomy (e.g., enabled and or empowered), competence (e.g., recognition and or development), and relatedness (e.g., inclusiveness, the sharing cultural values, and beliefs). Autonomy fosters empowerment via trust, competence, and a sense of connection and belonging. Bidee et. al. (2013) examine that fulfilling the three fundamental psychological requirements greatly enhanced the volunteers’ commitment and exertion, increasing their autonomous motivation. This principle also extends to personnel and affected communities during emergencies and disasters.

Academic research has influenced leadership and management, often from models derived from the military, which invests heavily in these principles. Many modern Western militaries have embraced the concept of mission command, and recent work on self-determination theory has significant similarities. The foundation of SDT rests on empirical research that utilizes rigorous psychological methodologies such as experimentation, standardization, and statistical conclusions. Although adopting these practices appears to progress slowly, it is closely associated with well-established and enduring leadership principles. One illustration is the military principle of Mission Command (US Air Force, 2023; Wikipedia, 2014). Mission command utilizes mission orders, and commanders focus on competent people and teams rather than the detailed direction when tasking. The guiding principles of Mission Command consist of six key elements: fostering cohesive teams through establishing mutual trust, promoting the development of shared understanding, articulating a clear commander’s goal, encouraging disciplined initiative, employing mission orders, and embracing sensible risk-taking. These six principles mirror the concepts required in emergencies and disasters to promote unity, collaboration, and support interoperability.

The military’s mission command approach, exemplified by the American and Australian models, emphasizes the importance of clear orders and intent, decentralized decision-making, and trust. These principles foster unity of effort in complex operating environments while allowing flexibility and adaptability.

Australian and New Zealand “National Council for Fire and Emergency Services” (AFAC) advocates the implementation of the mission command concept to manage activities across diverse locations in Australia effectively. Incident Controllers and Commanders must communicate a commander’s intent and ensure that subordinates are provided with the necessary resources to achieve the specified mission objectives. This is crucial for maintaining flexibility and adaptability to meet the commander’s intent. The method enables nimble and adaptable leaders to carry out the mission.

Due to the exact characteristics of mission command and SDT and their ability to function effectively in intricate contexts, SDT holds substantial merit for use in emergency management. The military operates in a defined environment based on the threat; the same can be said for emergency services and other agencies in emergencies and disasters. Leaders must be able to make decisions independently while still adhering to mission orders, policies, procedures, and laws. Additionally, they must be proficient in executing orders and comprehending the underlying intentions. Trust, a shared sense of goals, and cultural norms are fundamental elements that guide their actions.

The Demand for Ethical Leadership Among Contemporary Leaders Is More Pronounced

Ethical leadership has gained significant prominence during the early 21st century. Several well-publicized corporate ethics scandals occurred between 2000 and 2003, including those involving companies such as Enron, WorldCom, Arthur Andersen, Qwest, and Global Crossing. Within emergency management, a post-review of Hurricane Katrina noted ethical failures, including FEMA repeatedly blocking the delivery of emergency supplies ordered by the Methodist Hospital in New Orleans from its out-of-state headquarters and the Red Cross being denied access to the Superdome in New Orleans to deliver emergency supplies to name just two examples (Edwards, 2015).

Recognition of the significance of ethical leadership and consideration of stakeholders’ long-term interests is increasingly widespread (University of Minnesota, 2015). Contrary to conventional management methods, ethical leaders’ primary responsibility is their ethical conduct towards employees, customers, and the wider community. Ethical leaders establish trust and maintain ethical behavior by possessing a solid basis in integrity, namely moral beliefs.

The evaluation process for the Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct for Emergency Management Professionals (the Code) is currently underway at the request of the FEMA Ethics Special Interest Group (SIG) (FEMA/EMI, 2022). Despite the soundness of the Code’s foundations, emergency and disaster management definitions are absent. The Code is built around a number of Foundational Tenets:

- Think ethically, act morally,

- Obey the law,

- Maximize the good done for people and society, taking into consideration the needs of the most vulnerable,

- Respect the rights of people and organizations,

- Fulfill duties and obligations to those served,

- Build trusting relationships, and

- Use ethical decision-making processes when faced with an ethical dilemma.

Supporting the Tenets, 28 standards have been identified in the areas of:

- Responsibility to affected populations,

- Responsibility to partners, stakeholders, and the public,

- Responsibility to the environment,

- Responsibility to colleagues,

- Responsibility to employers,

- Responsibility to the profession, noting that “the profession” has yet to be formally established, and

- Responsibility to self.

Increasing Need for Expertise in Management

The digitalization process is causing significant and transformative changes within companies and their immediate business surroundings, leading to a faster decline in the effectiveness of the existing business model (Wirtz et al., 2022). The emergency management environment is not immune. Rather, due to the interrelationship with Government, organizations, and communities, it is directly at the forefront of these implications. The advent of digitization and digital technologies, such as video conferencing, digital data analysis, and social media, has introduced new uncertainties that previous management practices cannot adequately address. This has brought organizational change to the forefront despite the potential challenges it may pose. The Internet provides access to information that can either be overwhelming or, through various programs’ digital technology, selectively offer biased material that restricts exposure to different perspectives and ideas.

By coalescing Wirtz’s work into four critical perspectives, management must grasp how to navigate organizational change: technical impact, compartmentalized adaptation, systemic change, and holistic co-evolution. The impact of artificial intelligence, robotics, and the Internet on organizational architecture is a clear example of organizational change.

Adopting a digital approach to management is expected to become the focal point of internal and external interactions, leading to changes in organizational structure and management practices. Managers will face a significant challenge in adapting to a new approach, which involves not just passively observing and responding to changes but also actively engaging in data analysis as a management strategy to extract valuable insights from the overwhelming amount of information available.

The most arduous aspect of emergency management leaders and managers is organizational reform, which is the alteration of culture due to the impact of generational change and inter-relationships with a wide range of entities. Cultural transformation refers to the process by which a company promotes the adoption of behaviors and attitudes that align with its values and beliefs among its personnel. Why is this important? Values and beliefs influence behavior. Although laws and procedures can set limits and guide actions, employees, volunteers, and the community must exhibit positive behavior aligned with the mission during emergencies or disasters.

By integrating modern leadership with contemporary management, we provide coherence in strategizing, guiding, coordinating, and overseeing operations to accomplish the organization’s objectives (e.g., mission orders). Every emergency management manager is responsible for accurately identifying and adjusting resources efficiently. To accomplish this, they must have adopted emerging practices, namely in digital acquisition and examination, social media, and other online communication platforms. In addition, they must advocate for the organization’s culture and leadership strategy when implementing and embracing new systems and practices.

Critical Thinking and Decision-making

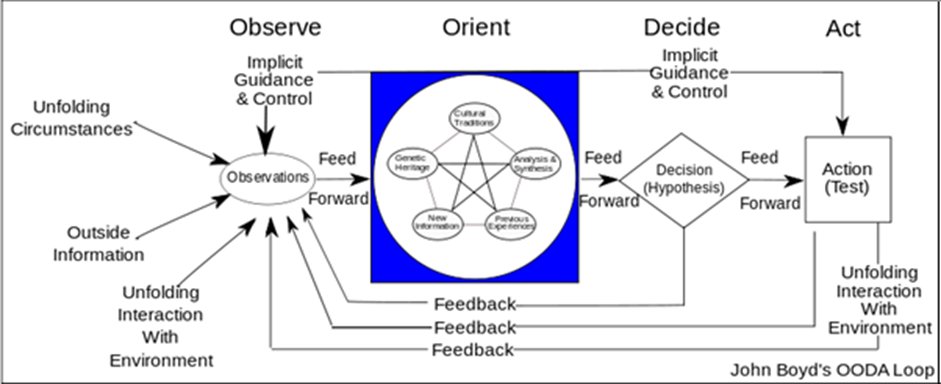

Critical thinking is analyzing and evaluating information to make informed and logical choices. Boyd’s Observe, Orientate Decide and Act Loop (OODA) (Moran, 2008), consisting of observing, orienting, determining, and acting, is widely recognized as the fundamental framework for military decision-making and has also been adopted by several disaster management groups. Initially, this term was used in the context of combat operations, but it is more commonly used at the strategic level in military operations. The concept was conceived by John Boyd, a military strategist and Colonel in the United States Air Force (Tremblay, 2015). The OODA loop has gained widespread acceptance in business and military strategy. Boyd proposes that decision-making follows a repetitive sequence of Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act (OODA). The OODA Loop model closely correlates with the Plan-Do-Check-Act framework (Tague, 2005). Both emphasize the significance of precisely understanding a situation, ensuring that the activities taken are producing the desired outcomes, and making necessary adjustments.

Boyd’s theory and its application to emergency or catastrophic mission. It is promoted through various police and emergency service web-based information providers (e.g., Police1.com, 2012 and FireRescue1.com, 2014). The analysis provides a clear definition of systematic operations as follows: The process of observing, collecting, and analyzing information leads to the generation of actionable information, which in turn establishes a shared knowledge of the situation. Orientation entails analyzing the shared operational information to determine the most probable and high-risk scenario and selecting the appropriate course of action.

For instance, after deciding and implementing an action plan, the Incident Controller or Commander is normally required to monitor feedback from multiple sources, such as the Incident Management Team, social and other media, including stakeholder feedback. This is done to update the overall understanding of the situation and assess the speed and effectiveness of the plan. As a result, the loop restarts based on the newly identified intention to adapt to the evolving requirements in the operating environment. This iterative procedure facilitates the ongoing evaluation of risks and mission requirements to ensure that operations align with the evolving nature of a dynamic and fluid event.

Thus, the leadership critical thinking and decision-making approach style employed by the U.S. and Australian military is well-suited for managing emergencies and disasters, just as it is for military operations. Utilizing this ensures that an Incident Controller or Commander can effectively make judgments and implement measures in a chaotic scenario while strictly adhering to the organization’s established standards and processes.

The fundamental principles of mission command include a well-defined purpose, confidence, proactiveness, comprehension of the situation, desired goals, knowledge of subordinates, delegation of authority, and the willingness to take calculated risks. These principles can be comprehended by anyone from any background (Glenn, 2020). With this method, leaders delegate more autonomy to subordinate leaders in carrying out their mission. This freedom is necessary in situations that demand prompt and resolute action, where well-trained subordinates willingly assume responsibility. Subordinate leaders who have received training in this manner may continuously operate following the organization’s decision-making process and respond effectively to immediate situational developments. This enables individuals to possess flexibility, adaptability, and the ability to capitalize on opportune moments for their actions.

To avoid the potential negative consequences of this independence, a cohesive approach and coordinated efforts, together with effective policies, processes, and a nurturing environment, are necessary to achieve mission-oriented leadership and success. The acquisition of trust, familiarity, and experience through training serves as the fundamental basis for implementing mission command in operational scenarios (Glenn, 2020).

The Australian joint doctrine emphasizes the importance of exercising mission command without taking undue risks while retaining decision-makers ability to be flexible and adaptive. This aligns with flexibility and adaptability, which are crucial for effectiveness in unexpected situations, as stated in the Australian Defence Doctrine Publication (ADDP) 2009.

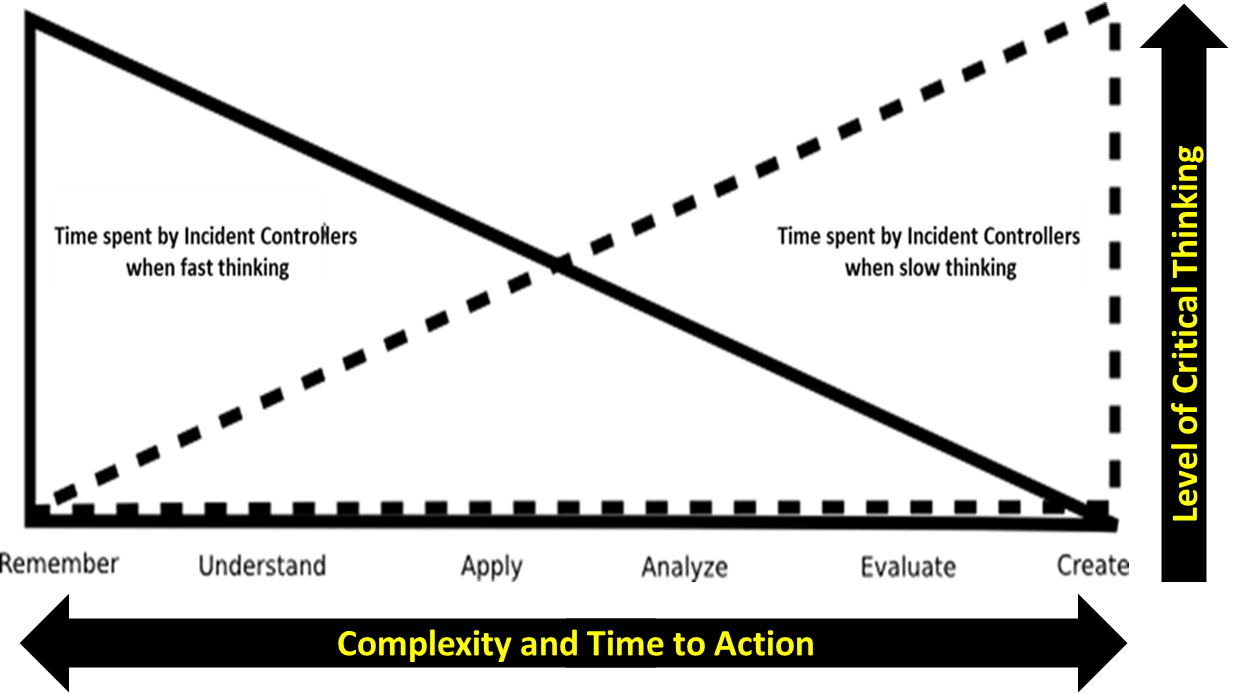

Effective emergency management, especially during emergencies and disasters, necessitates the application of contemporary critical thinking methodologies like OODA. The need for change is propelled by the digital realm and technology, which has led to a worldwide dissemination of information. An up-to-date approach to critical thinking must encompass both rapid and deliberate thought. The book “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” by Kahneman (Kahneman, 2011), offers valuable insights into the influence of cognitive processes on critical thinking and decision-making during emergencies or disasters.

Kahneman elucidates the reasons for the human propensity to encounter difficulties in applying rationality and discernment. During emergencies and disasters, especially in emergency services settings, the most expedient decision-making strategies employed in high-risk, time-sensitive situations are categorized as naturalistic or Type 1/System1, as outlined in the Australian document, “An Operator’s Guide to SPAR(CD): A Model to Support Decision-Making” (Launder and Penney, 2023.). This understanding of how people vertically think (Type 1/System1 – fast and intuitively and Type 2/System2 slow – methodical) approaches are commonly utilized in training firefighters, police officers, paramedics, and military personnel so that there is an understanding of the depth of critical thinking that needs to be adopted based on the time available before decision-making. This is crucial when faced with severely constrained decision-making time, the implications of initial decisions, and deeper follow-up critical thinking as time permits. Lauder and Penny’s research indicates optimizing decision strategies is predominantly employed in extensive and prolonged emergencies. This is particularly relevant when decision-making involves multiple personnel within an incident management team under the coordination of an Incident Controller or Incident Commander. The aim is to allow sufficient time to analyze broader potential probabilities, considering the potential for severe consequences such as loss of life and property and economic and environmental damage resulting from inadequate decisions.

Kahneman’s System 1 thinking entails linking novel information with preexisting patterns or thoughts rather than generating new patterns for every new encounter. For instance, a Function Manager in an Incident Management Team (IMT) may perceive the occurrence as conforming to previous encounters rather than recognizing the disparities.

In Kahneman’s model, fast thinking involves utilizing memory and comprehension during an emergency or disaster, while slow thinking requires analysis, evaluation, and creation. Upon the arrival of an Incident Controller or Commander at the scene, particularly in time-sensitive situations, there is a higher probability of relying on intuition and pattern recognition in the decision-making process (U.K. Centre for Research and Evidence in Security Threat, 2023). Nevertheless, when enough time is available or when the level of complexity rises, the Incident Controller must employ a more thorough and intentional method for examining the operational environment. During the process of critical thinking, certain biases might hinder its efficacy. There are many examples. The primary ones included here and will be discussed in turn:

- Anchoring refers to cognitive bias where individuals rely heavily on the initial information they receive when making decisions.

- Availability bias is the tendency to overestimate the likelihood of events based on how easily they come to mind.

- Substitution occurs when individuals simplify complex decision-making tasks by substituting them with more straightforward, more easily answerable questions.

- Optimism and loss aversion are psychological biases where individuals tend to be overly optimistic about positive outcomes and are averse to losses.

- Framing refers to how information is presented, which can influence decision-making by highlighting certain aspects and downplaying others.

- Sunk-cost fallacy is the tendency to continue investing in a decision or project based on the resources.

A. Anchoring

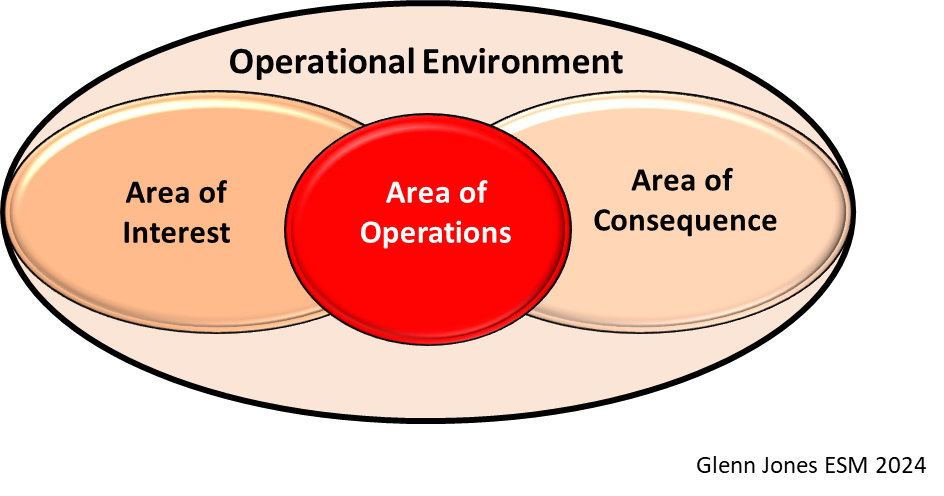

Refers to cognitive bias, where individuals rely heavily on the initial information they receive when making decisions or judgments. The “anchoring effect” refers to the inclination to be swayed by numbers not pertinent to the situation. In a flood, an emergency manager may prioritize the information provided by a dam’s output, disregarding the varying data from river gauges. These gauges may indicate additional water inputs or the effects of unmeasured water. Empirical studies demonstrate that the immediate surroundings significantly influence our conduct to a greater extent than we are consciously aware of or desire. Our tendency to anchor can hinder our ability to focus on critical and consequential areas during emergencies or disasters. Focusing solely on actions within the designated area of operations, as outlined in the Australasian Inter-Service Incident Management System (AIIMS, 2017), may hinder our ability to explore additional areas of importance. The region encompassing these components inside the United States is called the operational environment.

B. Availability

This heuristic is a cognitive shortcut that individuals employ to assess the likelihood of events by relying on the ease with which they can recall examples and the belief that such events must hold significance. The peril is in creating a notion of the enormity of the repercussions of an action or its level of importance. Emergency managers play a role in assessing and evaluating hazards. Immediate consideration of high risk may not correctly correspond to the actual likelihood of such risk. An instance of standard error may arise when the allocation of effort prioritizes a low level of significance rather than taking into account the total relevance of the task. For instance, an emergency manager gives higher priority to fixing homes rather than clearing key supply routes.

C. Substitution

System 1 thinking often simplifies complex questions or assumes fresh information has a similar effect rather than considering its exponential impact. The issue lies in the fact that this approach contradicts the principles of probability, as exemplified by fires that are influenced by diverse, dynamic factors such as weather, terrain, and fuel quantities. When attempting to predict operational actions over a specific period, inquiring about the destination it will reach in four (4) hours rather than the factors that will influence the fire’s trajectory and velocity in the following four (4) hours may overlook or fail to adequately consider individual implications and the prospective repercussions.

D. Optimism and Loss Aversion

This bias creates the false perception of having control. The planning fallacy refers to the inclination to overestimate one’s capacity to influence an emergency or disaster or to control events based on past experiences rather than the current available data. Kahneman (Kahneman, 2011) presents the concept he calls “What You See Is All There Is” (WYSIATI). The Theory posits that the mind predominantly considers familiar and previously witnessed phenomena while making decisions. The theory seldom takes into account “Known Unknowns,” which are occurrences that it recognizes as important but lacks information on. Ultimately, it seems completely unaware of the existence of “Undetermined Unknowns,” which are unidentifiable occurrences with undetermined significance.

In emergencies or disasters, the Incident Controller should be aware and thoroughly examine what is known, what is known to be unknown, and the possibility of unforeseen unknowns. By considering the area of interest, area of operations, and area of consequence collectively, one can effectively apply critical thinking to analyze the potential outcomes in each area. This involves systematically evaluating the spectrum of consequences and posing hypothetical scenarios by asking, “What if?” An illustration of profound contemplation in this context is the range of three (3) to five (5) occurrences.

E. Framing

The act of intentionally shaping or presenting information in a particular way to influence how others perceive it. Framing refers to the specific circumstances or environment in which decisions are presented. During emergencies or disasters, it is imperative for decision-makers to transmit information that is logical and based on evidence effectively. When informing the community about the dangers of staying in a fire-prone region or a structure that will be flooded, therefore, communicating the risk, potential consequences, and the timescale involved is important. This helps the community to make a well-informed decision.

F. Sunk Cost

During an emergency or crisis, decision-makers must be cognizant of the risk associated with persisting in response techniques that are either ineffective or have little chance of yielding improved outcomes. Consistent assessment and objective commitment to a specific, well-rounded strategy are crucial, along with the capacity to acknowledge the necessity for a change in approach instead of persisting with an inadequate plan to evade sentiments of remorse or defeat. This strategy remains applicable even in the presence of community pressure to continue.

Framework for Intentional and Analytical Thought Process and Decision-Making

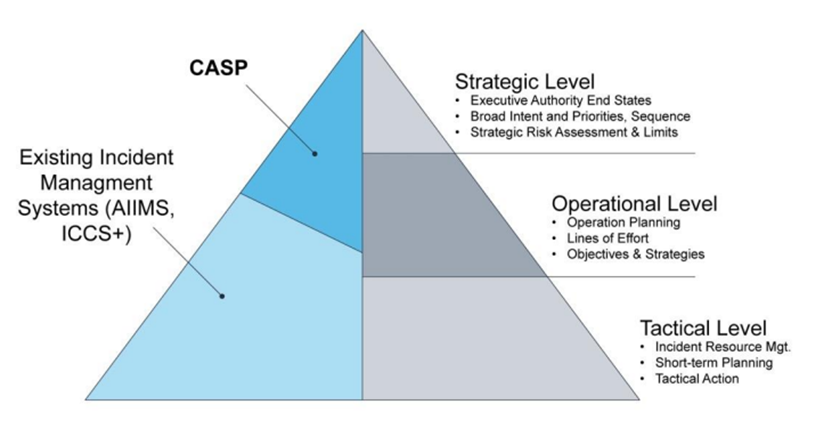

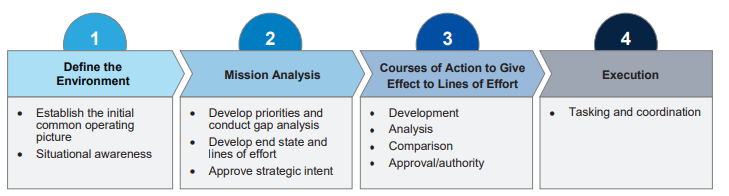

The “Crisis Appreciation and Strategic Planning (CASP) Guidebook” (Department of Home Affairs, 2022) offers a methodical approach to analyzing intricate situations. The CASP employs tools that enable the timely integration of information from various sources and explores how government, not-for-profit, and private-sector endeavors can collaborate to deliver a cohesive response. The Guidebook asserts that the command-and-control approach is insufficient for effectively managing catastrophic disasters in the complex and unpredictable situations they provide. This is particularly true at the strategic levels of planning and decision-making. These emergencies are characterized by their recurrence and Volatility, as well as their Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity (VUCA).

The Guidebook explains the integration between CASP and AIIMS. AIIMS has built incident-management structures organized hierarchically. Nevertheless, this does not accurately depict the implementation of crisis management. Individuals at all hierarchical positions collaborate and coordinate with one another at all levels to attain triumph in the process of organizing disorder.

Each step of the CASP method is defined as:

- Describing the Environment: Establishing the environment results in constructing a unified operational representation, as described by CASP. The common operational picture (COP) encompasses situational awareness and entails studying and interpreting existing and potential conditions. The activity may involve deliberation and conceptualization regarding the outcome of the procedure. Incorporating a substantial number of planning team members in this stage aids in cultivating a comprehensive and collective comprehension of the surroundings. When defining the environment, CASP states the importance of considering not just the operational area but also the areas of interest and consequence.

- Evaluating the mission: Mission analysis primarily focuses on the strategic objective, which involves considering several courses of action to achieve a desired outcome. The end state refers to the final condition of the environment once the specified success conditions have been achieved. After a disaster, communities typically need to adjust to a new state of affairs. Establishing a final objective aids in determining the desired state of affairs. The final objective embodies a feasible concept to synchronize strategic and operational activities. After the issuance of the strategic intent, planners arrange various courses of action to define the specific conditions for success required to reach the desired end state. By developing lines of effort, the crisis is divided into manageable and purpose-driven actions such as medical treatment, triage, transport, evacuation, shelter, and infrastructure restoration. Each of these actions may have specific end goals and objectives. The lines of effort consist of pragmatic and feasible measures that uphold the strategic objective

- Creating strategies for action: Emergency managers formulate strategies by defining large-scale actions and assessing those actions and associated factors necessary to achieve objectives. Implementation and coordination of tasks entail dividing the large-scale courses of action into specific tasks and assignments suitable for resources such as incident management teams or strategic airlifts. The format of these duties and assignments is contingent upon the policies and standards particular to each agency. Irrespective of their format, tasks and assignments must align with the strategy objective and be linked to related strategic priorities. By doing so, operational and tactical personnel comprehend how their tasks align with and contribute to the overarching goals.The Military Appreciation Process (MAP), which encompasses a structured approach to review facts, make assumptions, and arrive at logical solutions, incorporates top-down planning and evaluates scenarios post H-hour (the designated start time for an operation) that then apply a manoeuvrist approach to developing a course of action is applied by a number of Western Defence Forces and has been adopted by a number of Australian emergency services generally applying the following procedures: a). preliminary Analysis and Intelligence Preparation of the operational environment, b). defining the Mission (Mission Analysis), c). develop courses of action where time permits, and d). analyse the courses of action.

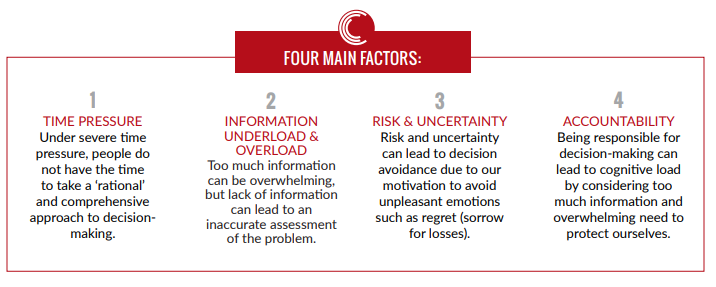

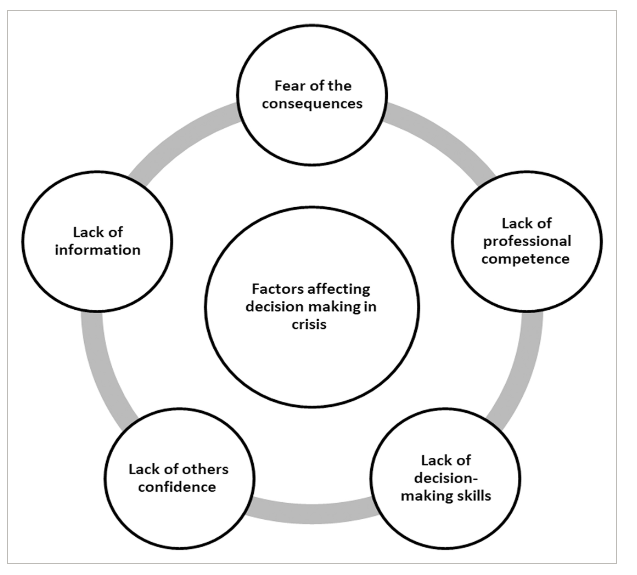

- Operational and tactical decision-making: Multiple variables influence operational and tactical decision-makers during emergencies and disasters. Frequently, these individuals face intense time constraints and high expectations, compelling them to make prompt decisions. Empirical data suggests that the utilization of heuristic thinking models, also known as “rules of thumb,” to simplify intricate problems or decision-making processes, as well as the manifestation of “decision inertia” among decision-makers, can lead to delays or even a complete lack of action Centre for Research and Evidence in Security Threat (Alison, 2020). Heuristic models can expedite decision-making when decision-makers possess extensive knowledge and competence, even when information is limited. Various factors can influence decision-making, as shown in Figure 7.

Research on the COVID-19 pandemic crisis in Australia identified several stages or steps of decision-making, from defining the problem to collecting and classifying information to the status of alternatives and making a better selection to improve decision-maker efficiency. The steps were:

- Defining and diagnosing the problem. The researchers considered this one of the most important stages, requiring careful and proficient performance.

- Identifying possible alternatives . This is the process of selecting alternatives from the available information on most of the proposed options and solutions and considering their advantages and disadvantages.

- Scientifically evaluating the alternatives. This includes choosing the best ones, drawing down to a choice between at least two options, and choosing one as preferred.

- Choosing the appropriate alternative. This entails considering the options, studying the positive and negative consequences, and choosing the solution that provides more benefit and less harm.

- Implementing and evaluating the decision and following it after choosing. The implementation process evaluates the beginning of the effects arising from the negative or positive results, the emergence of strengths and weaknesses, the start of assessing results, and how efficient they are in meeting the requirements.

The similarities to other forms of critical thinking and decision-making are self-evident, demonstrating the many applications for which the foundational elements are sound.

Critical Thinking and Decision-making Models that Systemize Operational and Tactical Decision-making

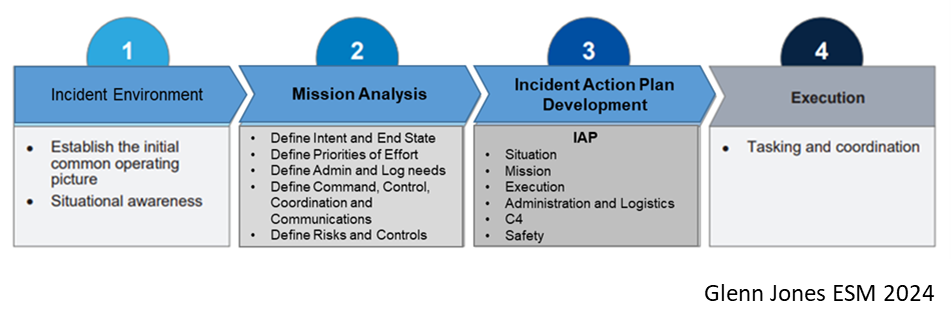

Operational and tactical decision-making can be eased by using an appreciation process. The Incident Controller must continuously assess operations, including potential contingencies that may arise in a dynamic environment. An adaption for operational and tactical decision-making based on the CASP Model might appear in the following manner:

International Approaches to Critical Thinking and Decision-making

For comparison to the findings of the literature that has already been discussed, the following international approaches will be mentioned in detail:

- The UK Decision Control Process,

- The UK Decision Control Process migration into Australia as SPAR(CD),

- United States (U.S.) Decision-Making Model, and

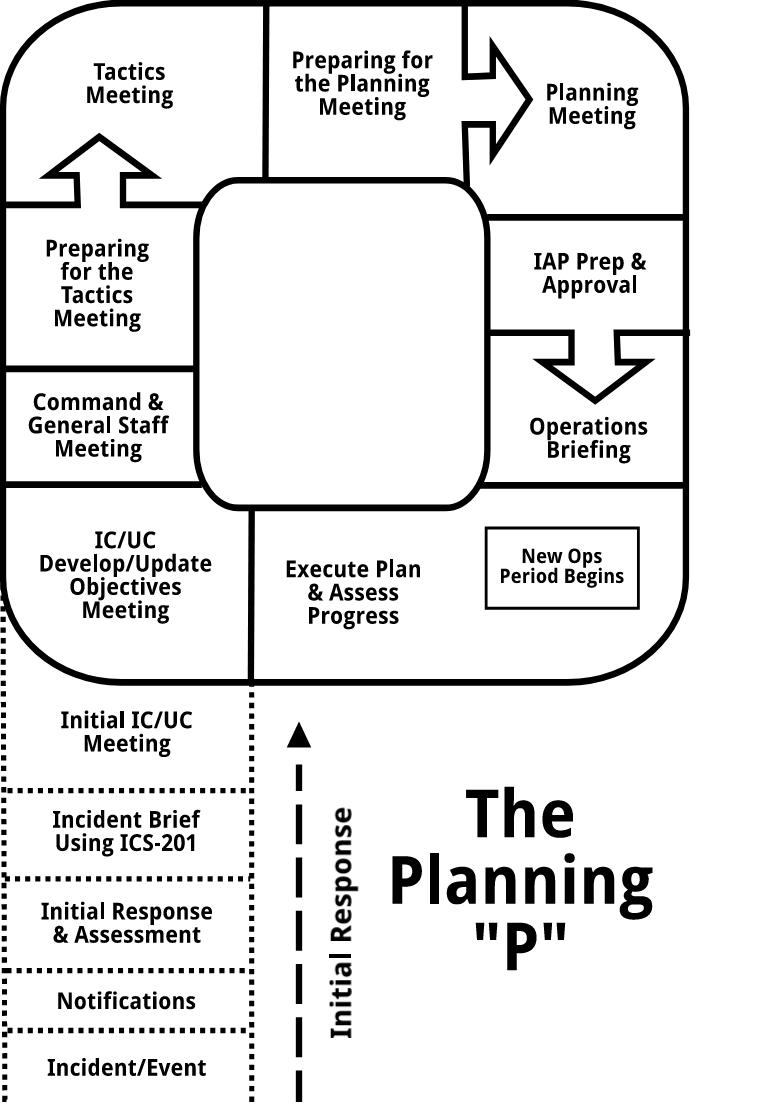

- The U.S. Incident Action Planning Process “The Planning P.”

The UK Decision Control Process

The London Fire Brigade adopted the 2017 Decision Control Process (DCP) to align with the National Operational Guidance (NOG). The DCP development came about following Cardiff University research to “better understand the decision making at operational incidents” published in March 2015 (Cohen-Hatton et al., 2015).

A case study in West London illustrates this approach. On 14 June 2017, a high-rise fire broke out in the 24-storey Grenfell Tower block of flats in North Kensington. The fire burned for 60 hours and led to the death of 72 people, more than 70 injured, and 223 escaping (Cohen-Hatton et al., 2015). The event was the deadliest structural fire in the United Kingdom since the 1988 Piper Alpha oil platform (Reid, 2020) disaster and the worst UK residential fire since World War II.

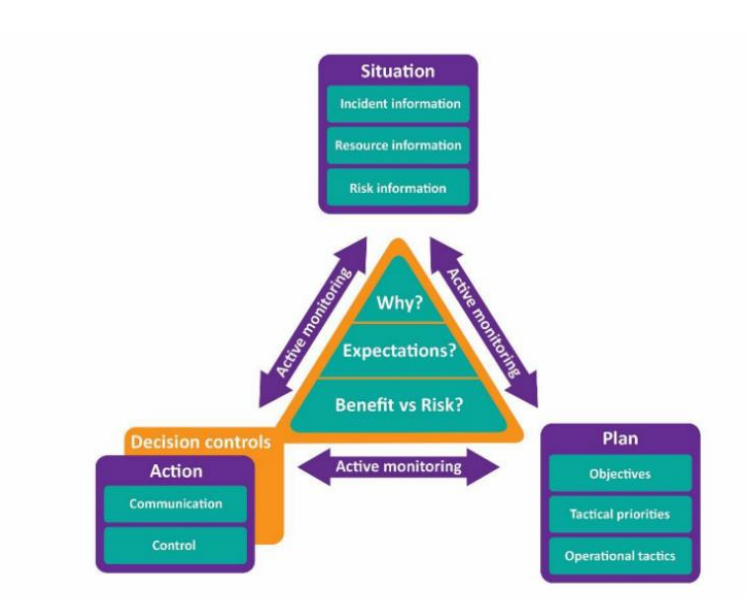

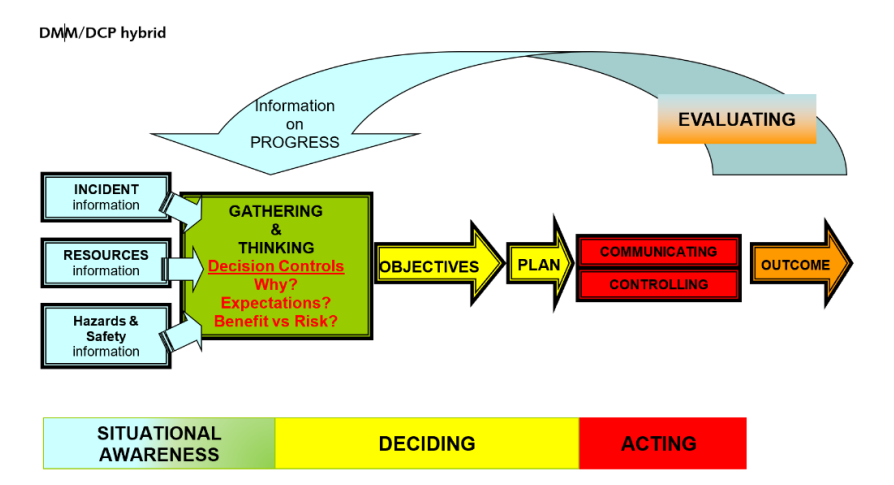

Then, as a result of the Grenfell Fire event and subsequent Inquiry, several critical observations and recommendations in April 2019 led the Commissioner of the London Fire Brigade to decide that the Brigade needed to reconsider the challenges and benefits of implementing such a fundamental change to the application of the DCP Model (Cohen-Hatton et al., 2015). An independent assessment recommended a hybrid model, as shown in Figure 10.

The hybrid model is similar to the OODA Loop and Mission Command approaches except for clarity of intent. Intent is paramount to guiding Incident Controllers and Commanders when applying their discretionary powers.

The UK Decision Control Process Migration into Australia as SPAR(CD)

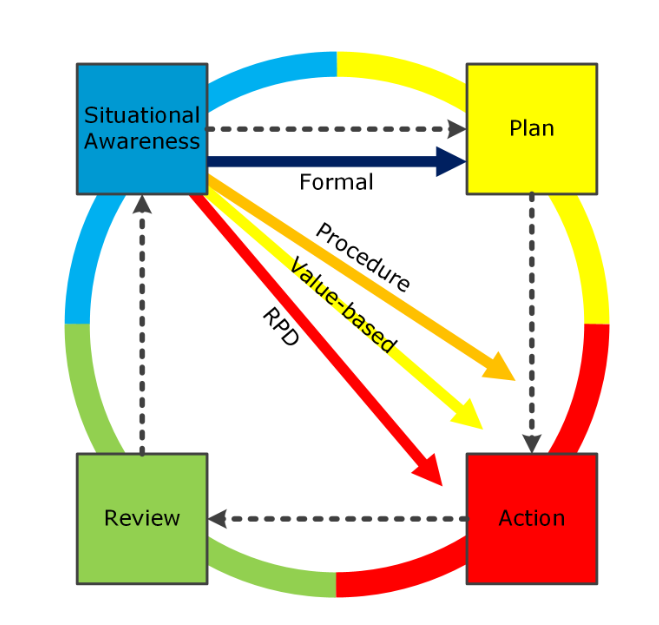

The SPAR(CD) model consists of six constructs: Situation Awareness, Context Assessment, Decision-making, Planning, Action, and Review. During a peer assessment of the Australian operator’s guide for SPAR(CD), Launder and Penney (2023) aimed to enhance the decision-making process in emergency services including police, military, ambulance, and firefighting. By analyzing more than 10,000 English-language studies on threat assessment, sense-making and critical decision-making, the researchers were able to refine the Situation-Plan-Act-Review (SPAR) Decision-Making Model developed by Dr David Launder, which is used in urban fire service operations in Australia. Although the South Australian Metropolitan Fire Service currently utilizes a previous iteration of SPAR, the recently published Situation-Context-Decision-Plan-Act-Review (S(CD)PAR) Decision Framework (Launder and Penney, 2023) and the Australian SPAR(CD) Model (Launder and Penney, 2023) has gained significant traction since its release in late 2023. At the Australian Institute of Police Management (AIPM), both the framework and the model are part of the curriculum. The institute provides training to personnel not just the different Police Forces but also numerous Emergency Services in Australia and the Pacific region. The Department of Fire and Emergency Services (DFES) in Western Australia has incorporated it into the professional development program for officers. As of November 2023, Fire and Rescue in New South Wales is evaluating SPAR(CD) as a potential formal operational decision model. SPAR(CD) constructs were identified by reviewing industries with high-risk levels and can be applied based on the circumstances.

- Situational Awareness (Perception). This is a review of one’s surroundings and current situation. In the earliest decision-making phase, the makers analyze and comprehend one’s surroundings. This is done by obtaining and understanding crucial or high-priority information.

- Context Assessment (Evaluation of the situation). The correlations between evaluating the nature of the context (including factors such as the complexity of the problem, time constraints, level of risk, and level of confidence) and choosing appropriate decision-making methods are of utmost importance.

- The Decision-making. Both SPAR(CD) Models outline a range of decision-making approaches, spanning from rapid and instinctive to structured techniques. Rapid decision-making strategies prioritize circumstances with limited time and high levels of risk, in which the decision-maker relies on recognition primed (based on experience) and intuitive processes.

Type 1 decisions refer to operational or tactical decision-making. The subsequent decision method is “value-based,” wherein decision-makers rely on their ethical or moral ideals and their sense of right or wrong in a particular situation. Although these tactics expedite the decision-making process, they also risk introducing errors and biases into the decision-making process. During the process of making quick decisions, cultural or organizational values can consciously and unconsciously affect how risks are seen and how willing one is to take risks. The third category of decision approach is called “procedural” decisions. Procedural decisions involve using established answers based on past experiences and written procedures to address known scenarios, risks, and difficulties.

Type 2 decisions refer to the process of making strategic decisions. Strategic decision-making involves using pre-determined decisions to carefully analyze several options to provide the most effective or creative solutions. This procedure is typically employed in situations when there is a possibility of decisions being scrutinized by others, including intricate and unclear high-risk circumstances, and requiring coordination among numerous agencies and decision-makers who must manage substantial situational information over extended periods.

- Planning (Strategizing). Strategic decision-making is the systematic process of establishing objectives, assessing different options, selecting appropriate strategies and tactics, and creating organizational or command structures to facilitate efficient coordination and logistical operations in developing the plan. Planning is the process of anticipating and preparing for a future scenario, as well as determining the most advantageous approach to pursue.

- Action (Execution). The execution of decisions, irrespective of the decision-making process, was a pivotal determinant of success or failure. According to the research, success in making quick Type 1 judgments depends on the decision-makers and their team members having both technical and interpersonal skills. Nevertheless, senior officers are obligated to implement decisions during emergencies or disasters, as the successful execution of plans relies heavily on promptly and practically translating decisions into actions.

- Review (Evaluation). Personnel initially deployed to these hazardous environments can actively and instinctively assess their initial understanding of the situation, judgments made, and effectiveness. As circumstances get more intricate and pose more significant risks, it is necessary to transition towards formal decision-making strategies that involve higher authority personnel and formalize planning, communication, coordination, and control processes. Choices must be made sequentially during extended emergencies or disasters, especially when operating in many campaigns. The review process allows decision-makers to execute a decision, analyze the results, and make adjustments before proceeding with new decisions or issuing new plans.

United States (U.S.) Decision-Making Model

Within the U.S., decision-making in a crisis is identified as a must. It must occur quickly and efficiently based on a comprehensive situation view. Effective crisis decisions are expected to take into account:

- Past: Standard practices, existing plans and protocols, and lessons learned. Good decisions made in planning and preparation will lay the groundwork for incident decision-making.

- Present: Situational awareness and a common operating picture.

- Future: Contingencies and anticipated needs.

In a crisis, the training recommends a quick decision followed by course corrections as new information becomes available, which is often better than waiting until all information is available before making a decision.

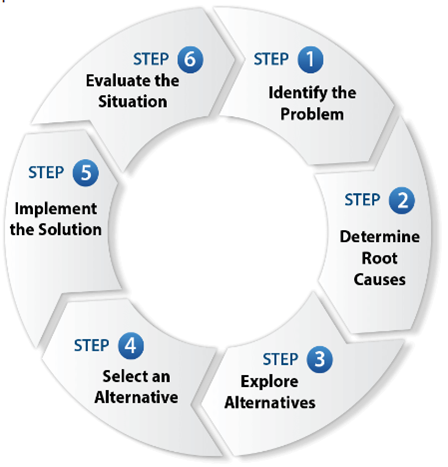

Within the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) training, the analytical approach has six steps, though they accept that any decision-making approach is acceptable. The six steps are identified as:

Step 1: Identify the problem. This step includes generating alternatives and evaluating them. You can create alternatives through brainstorming, surveys, discussion groups, or other means. Alternatives should be evaluated using a consistent process.

Step 2: Determine root causes. Determine the root or the core cause of the situation. There is no single approach to conducting a root cause analysis—the Why Staircase (ask why five times) is one.

Step 3: Explore alternatives. This step includes generating alternatives and evaluating them. You can create alternatives through brainstorming, surveys, discussion groups, or other means. Alternatives should be evaluated using a consistent process.

Step 4: Select an alternative. After evaluating each alternative, select the alternative closest to solving the problem with the most advantages and fewest disadvantages.

Step 5: Implement the solution. Implementation involves developing an action plan (what steps are needed), determining objectives or measurable targets, and identifying the resources required. Identifying details of the action plan (who will do what, by when, where, and how, as applicable). Using the plan to put the solution in place

Step 6: Evaluate the situation. Evaluation involves monitoring progress and evaluating the decision that was made. During evaluation, identify if the situation has changed, more or fewer resources are required, or a different alternative solution is required. Evaluation is an ongoing process.

FEMA promotes, within the analytical problem solving, applying the following process:

- Look for patterns, similarities, bubbles, and differences in the data,

- Draw inferences from the data and anticipate the unexpected,

- Challenge your assumptions and interpretations (if possible, do not depend on assumptions unless you can check them against evidence),

- Consider a contrary stance—try to disprove and confirm your theories—and do not ignore contrary evidence,

- Try to control for biases, prejudices, and conflicts of interest,

- Divide complex problems into sub-problems and work on them individually,

- Control variables in reasoning or testing to get better results,

- Keep environmental, legal, and social considerations in mind, and

- Combine the use of imagination with rational thinking.

The U.S. Incident Action Planning Process: “The Planning P”

The incident action planning process and incident action Plans (IAPs) are central to managing U.S. emergency service incident management practice. The model’s benefit lies in its capability to ensure the synchronization of operations and their alignment with incident objectives. When used effectively, the process also develops operational rhythm and structural consistency throughout the incident and consistency in communications.

Each section of the Planning “P” in brief can be described as follows:

- The Leg. In Planning P, the leg of the “P” describes the initial stages of an incident, when the objective is to gain situational awareness of the incident and determine the organization needed for incident management.

- Objectives Development/Update. It is essential to establish the objectives for the operational period quickly and thereafter to reassess and align new objectives to reflect the changing dynamic of the incident.

- Strategy Meeting/Command and General Staff Meeting. After determining the incident objectives, the command team and stakeholders meet to clarify the objectives and strategies necessary for their achievement.

- Preparing for the Tactics Meeting. Once consensus has been achieved, the Operations Section Chief (and other function heads for their areas) and staff prepare for the Tactics Meeting by developing tactics and determining the resources required.

- Tactics Meeting. In the Tactics Meeting, IMT function heads and critical players review the proposed tactics developed by the Operations Section and conduct planning for the demand, receive, and deploy resources.

- Preparing for the Planning Meeting. Following the Tactics Meeting, staff collaborate to identify support needs and assign specific resources to accomplish the plan.

- Planning Meeting. The Planning Meeting serves as the final review and approval of the operational plans and resource management plans.

- IAP Preparation and Approval. When concurrence from all functional sections of the IMT occurs, and the Incident/Controller/ Commander or Unified Command approves the plan.

- Operational Period briefing. When the IAP is released, functions in the IMT and operational commanders are briefed, and the execution is monitored for progress.

The cycle returns to the Objectives Development/Update following the last step.

The Impact of Timing on Collective Decision-making

The impact of timing on decision-making cannot be ignored. The critical thinking process can be applied in any situation, whether non-crisis or crisis. The main difference is the urgency of the situation and the amount of time that can be spent on each step.

Within the FEMA doctrine is the consideration of group decision-making. Group or team decision-making is often a good choice when:

- The situation is complex,

- Consequences are significant,

- Commitment and buy-in are essential, and

- There is time for deliberation and consensus building.

The advantages of group decision-making are considered:

- Generates more favorable outcomes,

- Provides a broader perspective,

- Taps creative potential,

- Allows increased discussion,

- Makes wider use of resources, and

- Builds ownership and buy-in.

The limitations of group decision-making are detailed as follows:

- Requires adequate time and good leadership to be successful,

- May result in a compromise rather than the optimal solution,

- Can be overly influenced by a vocal few, and

- May get bogged down by over-analyzing or influenced by haste to be finished.

To achieve effective group decision-making, the following practices will make the process more effective:

- Adding diversity,

- Forming smaller groups and working groups,

- Fostering consensus,

- Clarifying member roles, and

- Establishing ground rules.

Challenges in Collaborative Critical Thinking

The effectiveness of collaborative critical thinking lies in group dynamics, and self-determination theory directly links to high-performance teams, thus fitting the holistic application. The UK Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) published a Review of high-performance teams in 2023, stating, “… a team’s performance is, to a large extent – although not entirely, a result of the performance of its members” (Barends et al., 2023A, p. 3).

The review looked explicitly at the group-level factors influencing team effectiveness. Moreover, determined in summary, three critical areas are as follows:

- Team composition. The mix of team-member characteristics, and it includes age, gender, and level of education.

- Interpersonal dynamics. Team attitudes that develop as a result of the experiences of team members. Research literature terms this as emergent socio-affective states.

- Organizing knowledge. How vital knowledge is represented and distributed within the team. Research literature terms this as emergent cognitive states (Barendsetal, 2023b, p. 3).

However, within an emergency or disaster, the team composition is often pre-determined by the function or roles the individual fills. Still, the function or role does bring their ability to make decisions and are sufficiently enabled. Therefore, interpersonal dynamics are the determining factors for success for an incident controller or commander. Experience, relationship building, and ability to influence will determine how a collaborative team functions and develops courses of action or solutions.

The fundamental interpersonal dynamics are:

- Trust,

- Psychological safety,

- Team/social cohesion, and

- Knowledge.

In comparison to the self-determination theory, these interpersonal dynamics align as shown:

| CIPD High-performance Teams Role or function or participants |

Self-determination theory |

|---|---|

| Trust | Core elements of trust – honesty, integrity and loyalty |

| Psychological safety Team/social cohesion |

Relatedness |

| Organizational knowledge | Competence |

| Role or Function | Autonomy

|

Summary

There are a range of decision-making models, and most follow the basic principles:

- Gain situational awareness,

- Analyze the situation,

- Develop a solution or courses of action,

- Develop a plan, and

- Implement the plan and monitor.

The application of all elements and the depth of critical thinking are determined by the time to action and the complexity of the emergency or disaster. The depth of training and the collective use of a common approach to critical thinking will impact decision-makers ability to develop sound action plans and justify their decisions based on evidence, experience, and knowledge.

When emergency managers are engaged in collaborative critical thinking, using self-determination theory as a holistic approach enables the creation of high-performance teams without having to strategize a different psychological needs approach.

Challenges to Decision-Making

A 2020 study (Hallo et al., 2020) that looked at the effectiveness of leadership decision-making in complex situations and systems found, among other results, that:

- The vast majority (95%) of leaders engage in some level of subjective opinion to the extent that significantly impacts their decisions in complex situations.

- Only 41% of those surveyed sought input from immediate colleagues and friends.

This leads to the importance of being aware of the subjective content contingency planning and the lack of collaboration when confronted with complex situations. This survey adds weight to emergency managers’ importance in learning to become more effective and open to collaborative critical thinking.

Within the Australian COVID-19 research (Zeyad & Al-Dabbagh, 2020), it was identified that the decision-making process was affected by five factors, which are as follows:

- Lack of professional competence for decision-makers,

- Fear of the consequences of decision-making at a time of crisis,

- Lack of decision-making skills,

- Lack of others’ confidence about the decisions made, and

- Lack of information.

Competence, confidence, and capability can only be developed and retained through a range of professional development strategies, which may include exercises, academic research into the threat and the decision-making process, and strong and supportive organizational policies and procedures that provide actionable guidance, to name just a few.

Methodology

The chapter’s development was approached as a literature review where the sources were derived from a range of countries and included academic papers, emergency management guidelines, jurisdictional inquiries, course material, and topics from a range of international journals such as the Journal of Values-Based Leadership, Forbes.com, Organisational Psychology, American Psychologist, The Australian Journal of Emergency Management, The UK Centre for Research and Evidence in Security Threat and others from Sage.

In other cases, online courses provided insight into the practical application of critical thinking, decision-making, and ethics. For example, FEMA’s. S-0241.c: “Decision-Making and Problem-Solving,” (FEMA, 2023, S-0241.c.) and the Canadian Fire Dynamics Training. “Fire Control Module” (Fire Dynamics Training, Canada).

The methodology aimed to gain a comprehensive approach to the topics to avoid being single-nation-centric. The evolution of the inter-relationship of the issues emerged from the consistency in language models and insights from academics (with a focus on recent work post-2010 ideally) and professionals within the emergency management, psychological, and emergency management overarching organizations such as FEMA in the U.S., The National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) in Australia, the Australian and New Zealand National Council for Fire and Emergency Services (AFAC) and UN organizations such as The International Search and Rescue Advisory Group (INSARG) as examples.

The methodology selected allowed for comparison, contrast, and merging of different approaches, ideas, and lessons learned. While not all research led to inclusion in the chapter, those that did shaped the underlying principles and affirm assumptions that may not have otherwise been easily identified.

The objective was to present essential aspects of emergency management and their relationship to issues and challenges faced within leadership, management, critical thinking, and decision-making in a way that would inform, challenge, and generate discussion on these topics and the impacts of change in these areas of importance.

Findings and Solutions

This chapter has addressed various issues and challenges and identified opportunities for emergency managers. While many elements are interconnected, each is defined and amplified in the following sequence:

- Leadership. The core of a modern leader is creating the right environment (culture) and applying SDT.

- Management. The need for an integrated approach that promotes effective leadership.

- Critical thinking and decision-making. The importance of ethical intent and applying a systemic approach to analysis and rational decision-making.

Each will be discussed in turn.

1. Leadership

Individuals in positions of authority provide guidance and direction. Although much attention has been given to recognizing different leadership styles, there has been limited progress in implementing effective leadership practices, particularly in the context of SDT. In the emergency management context, effective leadership entails engaging with diverse individuals from different jurisdictions and organizations. Leaders must have a unified strategy to communicate with others and influence their behaviors. The use of self-determination theory is highly relevant to leadership in emergency and disaster situations.

Leaders can achieve autonomous action or decisions aligned with the mission objectives by connecting with affected populations and developing a solid grasp of the event and the available options or activities that can assist.

Engaging with a leader who follows SDT means that individuals express themselves by controlling their actions and feeling competent. They also form meaningful connections with others through caring relationships, where their contributions benefit society. This alignment of intrinsic values between the leader and the individuals ensures that their goals, behaviors, and needs are harmonious.

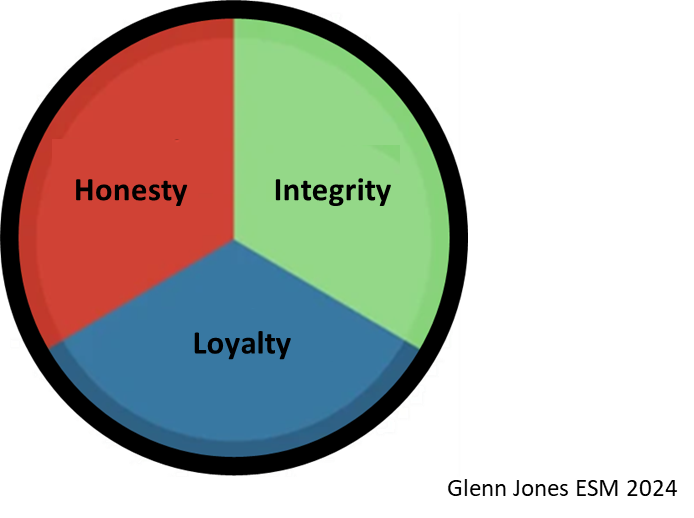

<p”>The Core of a Modern Leader

Based on the majority of leadership theories, the fundamental characteristic of a contemporary leader is trust, which is supported by the leader’s values and beliefs and influences their actions (Tracy, 2016). Theoretically, the foundation of a contemporary leader is trust, which is supported by the values and beliefs of the leader and influences their actions. Three fundamental components are necessary for trust in ethical and reliable leaders.

These components can be described as:

- Honesty. Honesty is demonstrated through transparency and openness. An Honest leader is willing to consult, collaborate, and communicate (speak and listen) both ideas and feelings. An honest leader follows through on commitments.

- Integrity. Integrity is a demonstration of the leader’s moral principles and willingness to speak up about actions that are not morally, ethically, or organizationally suitable. Integrity is also demonstrated by work ethic and conduct that would be deemed professional.

- Loyalty. Loyalty is demonstrated through trust and standing by superiors and subordinates when fit and proper. Leaders who are loyal both give and expect loyalty in return. It is the most fragile element of an ethical leader, complex to gain yet easy to lose.

These three elements are central to leadership and establish the behavior and foundation of a leader’s relationship with the organization, staff, volunteers, communities, and stakeholders. Honesty, integrity, and loyalty garner trust. Trust is lost when a leader is dishonest or lacks integrity. To lose one of the keystone elements is to lose all three.

Creating an Environment for Honesty, Integrity, and Loyalty to Thrive

The study conducted by Martela et al. (2018) in Frontiers in Psychology indicates that four psychological satisfactions across different cultures significantly influence work meaningfulness. These satisfactions include autonomy (feeling of volition), competence (feeling of efficacy), relatedness (feeling of caring relationships), and beneficence (feeling of making a positive contribution). Martela illustrates the significance of these elements in the global workplace by citing a survey conducted among 26,000 LinkedIn members in 40 countries. The poll reveals that 37% of the respondents prioritize purpose over money or prestige on a worldwide scale, with the percentage varying from 53% in Sweden to 23% in Saudi Arabia.

SDT (Ryan & Deci, 2000) is widely recognized as a prominent theory in the field of human motivation and well-being. Self-determination theory has discovered three fundamental psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. These requirements have been proven to have a crucial impact on individuals’ motivation, well-being, life satisfaction, and vitality in general and daily life.

Linking Self-Determination Theory into the Modern Leader Approach

SDT promotes the requirement to meet three psychological needs of the people a leader interacts with. These three needs are autonomy, relatedness, and competence, which create an environment for beneficence. The three needs are:

- Autonomy. People need to feel in control of their behaviors and goals. This sense of being able to take direct action that will result in real change plays a significant part in helping people feel self-determined. Self-determination does not mean people are independent of others or direction but instead constitutes a feeling of overall psychological liberty and freedom of internal will. For example, when giving a person a task and desired outcome and allowing them to choose the methodology to gain the result (within bounded constraints such as policy, procedures, and training, for example).

- Competence. People need to gain mastery of tasks and learn different skills. When people gain positive feedback, training, and information, they feel that they have the knowledge and skills needed for success, and they are then more likely to take actions that will help them achieve their goals.

- Relatedness. People need to experience a sense of belonging and attachment to other people. To be included and connected. When the proper environment exists, people are more likely to embrace the shared values and beliefs and drive behaviors that align with the team, organization, or community.

When placed into practice, the actions associated with the Self-Determination Theory in Action may include:

A. Relatedness in Action

- Involve all employees in inclusion,

- Treating all employees with respect, supporting their development, and ensuring they have a say,

- Actively champion and sponsor inclusion,

- Embed shared values and beliefs into policies and practices, and

- Consult and collaborate to gain consensus and understand current norms and values.

B. Competence in Action:

- Ensure all your people are competent in the organization’s policies and practices (bounded constraints),

- Ensure all your people are competent in the technical skills required for their role and progression,

- Ensure all your people are aware and practice positive cultural practices and behaviors,

- Ensure all your people are aware and practice appropriate behavior consistent with the organization’s code of conduct, and

- Ensure all your people are trained and encouraged to make informed decisions within organizational boundaries.

C. Autonomy in Action:

- Positive reflection and learning from mistakes,

- Encourage ideas and actions based on reason and logic,

- Build trust,

- Promote decision-making within boundaries, and

- Promote ownership and acknowledge subordinates’ efforts and ideas.

Self-Determination Theory in Action

Martela’s empirical study, which examines the relationship between autonomy, competence, relatedness, and beneficence in Finland, India, and the United States, strengthens the case for the adoption of SDT. The study found that SDT and its associated benefits significantly enhance the meaningfulness that individuals derive from their work, dedication, and effort.

2. Management

The research findings suggest that the models analyzed demonstrate consistent use of thoughtful, critical thinking and decision-making processes across the tactical, operational, and strategic environments in the U.S., Australia, and the U.K. Although this idea is fundamentally valid, the strategy should take into account the varying time and complexity factors for Incident Controllers and Commanders. The greater their familiarity with the process, the more constrained their time becomes. The intuitive and pattern-matching technique is based on understanding the broader ramifications and the necessity of allocating time to assess prospective or developing complexity and transition to a more profound critical thinking approach.

Therefore, by applying critical thinking and decision-making to all aspects of emergency management during non-operational times or regular exercises, operational decision-making and understanding of potential moments of transition can be significantly improved.

Additional investigation and comprehension of the complexities involved in critical thinking and decision-making can significantly improve the process of making emergency or disaster-related decisions. This is especially crucial during the transitional phases when shifting from tactical to operational and operational to strategic emergency or disaster management.

3. Critical Thinking and Decision-making

When comparing various critical thinking and decision-making models, it is uncommon to find explicit examples of how ethical principles are created. Penney et al. assert that ethical or moral values and the impression of right and wrong in a given context are only relevant in strategic decision-making. Under the mission command framework implemented by AFAC in Australia, the commander aims to grant subordinate commanders the autonomy to make decisions within established boundaries and instructions. When applied to critical thinking, this approach assists in determining the course of critical thinking along a comprehensive yet unambiguous route. If the intention is clearly expressed, incorporating the ethical principles of the Incident Controller or Commander, then subordinates are subject to ethical and ethically limited restrictions in their analysis and creation of courses of action.

Ethics should not be conflated with emotions, legal compliance, cultural or religious conventions, or scientific principles (Markkula, 2021). Primarily, ethics involves ensuring that a decision does not result in any moral harm. Furthermore, the application of ethics guarantees both social and legal justice. In other words, the decision ensures equitable treatment and falls within the jurisdiction of the decision-maker. The guidance is highly beneficial, as it achieves an exceptional equilibrium between positive outcomes and minimizing negative consequences. Finally, ethical behavior is in the best interest of the affected community or individuals harmed by an occurrence.

Embracing ethical intent will significantly strengthen critical thinking and the quality of the options developed for consideration by an Incident Controller or Commander. Ethical intent will also ensure that the decision meets the expectations of the impacted communities and is more likely to be validated on review.

Emergency management professionals must embrace modern thinking and approaches to adapt to changes in the environment, culture, and people with whom they interact daily. Embracing ethical intent as the core of critical thinking and decision-making establishes a foundation of a principled approach to critical thinking and decision-making that will strengthen and improve the defensibility of reproach when difficult and moral decisions are faced under pressure.

The significance of intention and the assurance of ethical critical thinking and decision-making

When comparing various critical thinking and decision-making models, it is uncommon to find explicit examples of how ethical principles are created. Penney et al. assert that ethical or moral values and the impression of right and wrong in a given context are only relevant in strategic decision-making. Under the mission command framework implemented by AFAC in Australia, the commander aims to grant subordinate commanders the autonomy to make decisions within established boundaries and instructions. When applied to critical thinking, this approach assists in determining the course of critical thinking along a comprehensive yet unambiguous route. If the intention is clearly expressed, incorporating the ethical principles of the Incident Controller or Commander, then subordinates are subject to ethical and ethically limited restrictions in their analysis and creation of courses of action.

Ethics should not be conflated with emotions, legal compliance, cultural or religious conventions, or scientific principles (Markkula, 2021). Primarily, ethics involves ensuring that a decision does not result in any moral harm. Furthermore, the application of ethics guarantees both social and legal justice. In other words, the decision ensures equitable treatment and falls within the jurisdiction of the decision-maker. The guidance is highly beneficial, as it achieves an exceptional equilibrium between positive outcomes and minimizing negative consequences. Finally, ethical behavior is in the best interest of the affected community or individuals harmed by an occurrence.

Embracing ethical intent will significantly strengthen critical thinking and the quality of the options developed for consideration by an Incident Controller or Commander. Ethical intent will also ensure that the decision meets the expectations of the impacted communities and is more likely to be validated on review.

Emergency management professionals must embrace modern thinking and approaches to adapt to changes in the environment, culture, and people with whom they interact daily. Embracing ethical intent as the core of critical thinking and decision-making establishes a foundation of a principled approach to critical thinking and decision-making that will strengthen and improve the defensibility of reproach when difficult and moral decisions are faced under pressure.

Discussion of Implications

Emergency Management leaders and managers are equally affected by the demands of the 21st Century as those in other work environments. These demands can be characterized as being a highly digital-driven society with the availability of vast amounts of information, both reliable and unreliable. The changing attitudes and views of employees, volunteers, and the broader society necessitate leaders and managers who continuously exhibit a strong ethical basis and trustworthiness. These values are imperative to establishing an atmosphere that fulfills the psychological requirements of employees, volunteers, and the broader community. The three psychological needs of SDT can be utilized to facilitate a leader’s interaction with employees, volunteers, and collaborative team leadership. Furthermore, these needs serve as the foundation for engagement tactics with communities affected by fires and climatic calamities.

For contemporary leaders to reach their full potential, the organization must possess structures, systems, policies, and procedures that align with the psychological requirements of its communities, personnel, volunteers, and stakeholders. Managers must align closely with leaders and enhance their organizations’ flexibility and adaptability to change.

Two conspicuous deficiencies in ethical decision-making during emergencies and disasters were the lack of sufficient elaboration and detail. The first requirement was that the critical thinking process incorporate factors such as those that are temporal, the time for critical thinking and the demand for a decision, and spatial observations, contingencies, and capabilities as examples of. In Australia, operational considerations are educated to utilize the PESTLE Model, which encompasses the analysis of Political, Economic, Sociocultural, Technological, Legal, and Environmental factors. Often, the addition of “O” for Operations does not take into account temporal or location factors.

The U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) examines the situation from a complete perspective that includes the past, present, and future. This approach is discussed in their course titled “Decision-Making and Problem-Solving” (2023) on slide 50. However, both fail to take into account the components of the operational environment, namely the area of interest, the area of operations and the area of consequence, to produce a comprehensive study of the event and its management of consequences.

In terms of ethical decisions, a literature review conducted in 2023 by Cuthbertson and Penney suggested that a guideline framework for ethical decision-making should be developed with community involvement. These actions will have repercussions and consider cultural and community norms such as the erosion of public trust, moral injury to staff, community divisiveness, moral distress, aggravation of inequalities, and/or conflict with personal or organizational ethics. Therefore, it is crucial to implement ethical decision-making in emergency management to avoid these potential adverse outcomes.

Emergency Management (EM) ethical practices can be enhanced through open and honest collaboration, seeking adequate information, overcoming hierarchical Power Structure, gaining consensus on managing resource constraints, and understating all stakeholders’ legal Boundaries. Listening to and seeking objective and technical knowledge and having insight into emotional factors. Moreover, all establish ethical implications and develop consensus toward a solution.

Incorporating an ethical purpose would provide explicit direction for evaluating an occurrence, guaranteeing that any approach aligns with legal, moral, and ethical standards. Employing a temporal and geographical framework and considering key aspects can ensure an exhaustive assessment of an event’s impacts and reactions on a community.

Greater proficiency and certainty in critical thinking and decision-making are necessary due to the effects of climate change and the ever-changing nature of fires and climatic emergencies.