19 Credentialing and Professionalization in Emergency, Crisis and Disaster Management (ECDM)

Christopher J Ainsworth MBA CEM® and Glenn Jones ESM CEM®

Authors

Christopher J. Ainsworth, MBA, CEM®

Glenn A. Jones, ESM, CEM®, BAdmin Lead (UNE), Adv Dip PS (EM), Dip PS (EM), Dip VET, Dip TAE-TDD, Dip QA1

Keywords

Emergency Management, Disaster Management, Crisis Management, Credentialing, Professional, Professionalization

Abstract

After Action Reviews (AARs) continue to show a shortage of skilled Emergency, Crisis, and Disaster Management (ECDM) personnel needed to handle the preparedness, immediate response, relief, and recovery stages of major incidents, which can quickly deplete local resources (Australia Royal Commission, 2020). The three domains of ECDM each have their unique characteristics, are interconnected and form a complex network. This is primarily because emergencies, crises, and disasters (ECDs) often overlap and influence each other, requiring coordinated responses across these domains. As a whole, each domain relies on a complex and interconnected network that is primarily backed by a limited number of reference sources. This means that these domains do not function independently. In addition, data collection in these areas is challenging due to the unpredictable and chaotic nature of emergencies, crises, and disasters (Du et al., 2020). The association network of activities and processes work together to manage emergencies, crises, and disasters (Cao, 2023). Individually, knowledge, skill, competency, aptitude, and expertise are all crucial for the successful and efficient handling of emergencies, crises, and disasters (Ellis, 2011.; McArdle, 2017.).

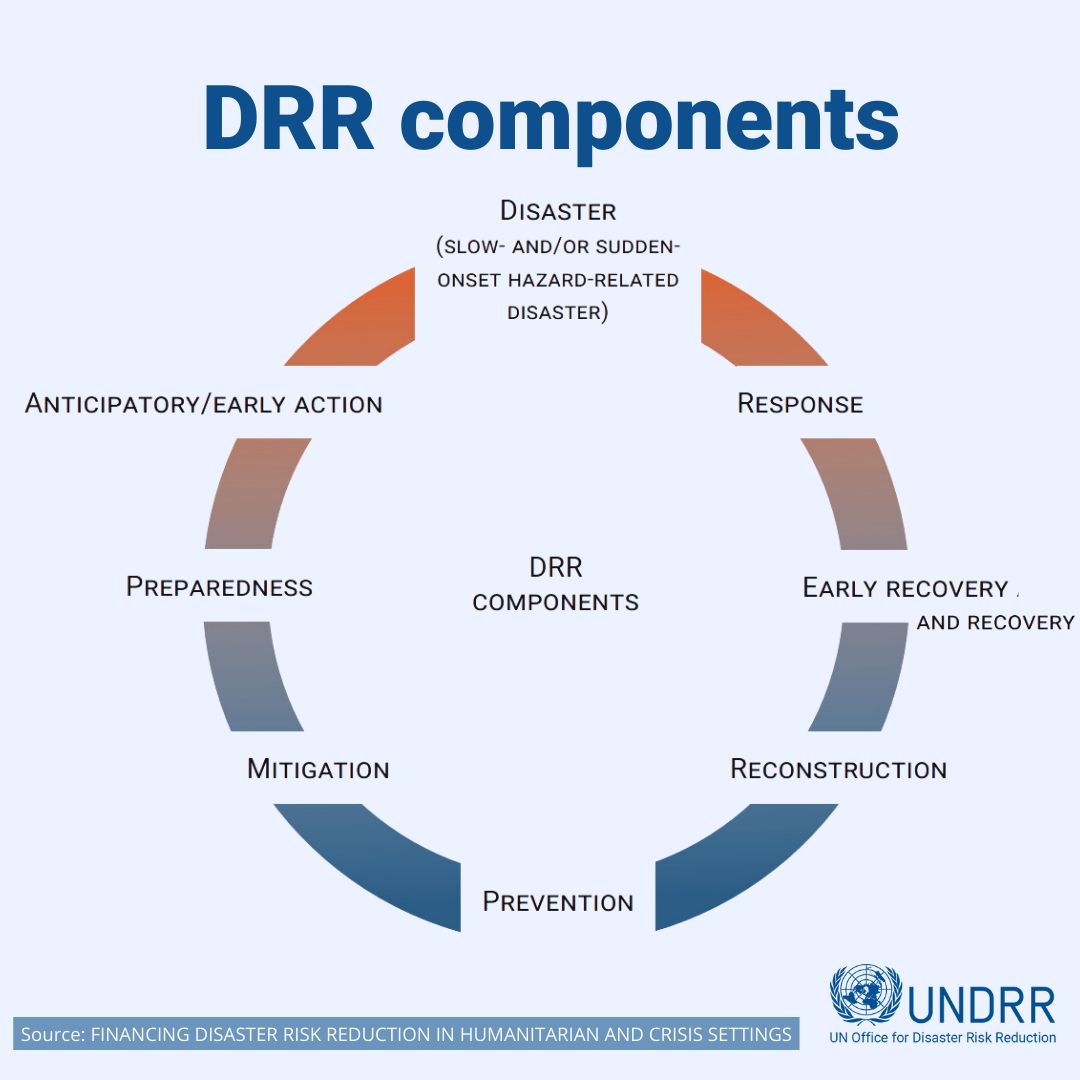

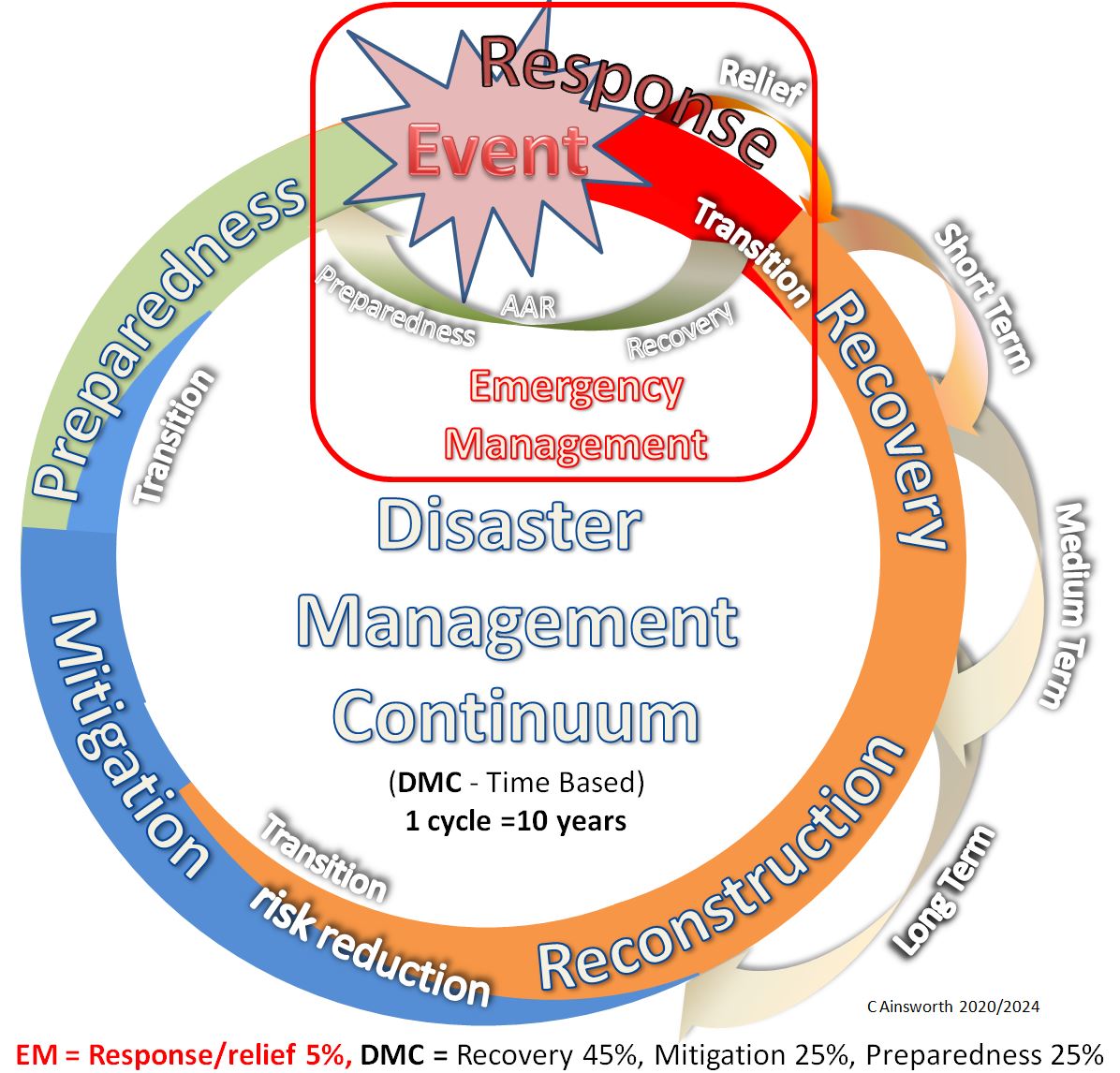

Current training in ECDM programs covers the basic principles within the Phases/Elements/Components (P/E/C) of Mitigation (also described as Prevention), Preparedness, Response, and Recovery (PPRR), offering practitioners essential information at a foundational level. Over time, practitioners gain the required understanding of different and integrated systems and procedures through experience and competency verification. Practitioners may then have the advanced skills to organize efficient, culturally sensitive solutions and promote diplomacy and cooperation at various levels – local, regional, national, or global.

The process of obtaining credentials and professional recognition in Emergency, Crisis, and Disaster Management (ECDM) is not a straightforward pathway but rather a complex network of conflicting notions, values, and jurisdictional prerequisites (Ahmed and Ledger, 2023). Education equips individuals with a fundamental knowledge base and practical skills, while certification serves as a validation of a practitioner’s comprehensive understanding, expertise, and proficiency in the field of emergency, crisis, and disaster management. As practitioners acquire proficiency and competence in various domains, they strive to advance toward professionalization. On a global scale, it is imperative for practitioners to have access to high-quality programs that empower them to make informed decisions on their professional goals and career paths within their local contexts. Based on the scarcity of evidence found through research, this chapter seeks to identify key milestones that may assist individuals plan and navigate their credentialing journey. The process of sector professionalization is still a minimum of one, if not two decades away (Cwiak, 2022).

Introduction

This chapter aims to conduct a comprehensive review and analysis of international credential offerings in relation to the PPRR (Mitigation/Prevention, Preparedness, Response, and Recovery) criteria of Emergency, Crisis, and Disaster Management. The objective is to identify potential practitioner pathways towards professionalization in the ECDM sector. A qualitative approach was employed to compose this chapter, incorporating action research and resources from international organizations, agencies, and associations. This study used academic articles, Google Scholar and Semantic Scholar search engines, sources from the FEMA/EMI Higher Education Program, information from organizational and state certification programs, and Oxford Dictionary definitions.

The efficiency of ECDM certification systems in bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge, practical skills, and real-world implementation is being scrutinized more as newsworthy events focus on ECDM with greater regularity and severity. The lack of professional acknowledgment can be attributed to a complicated interplay of situations and elements, encompassing various criteria including:

- Systemic biases and under-representation,

- Emphasis on individual achievements over collaboration,

- Limited visibility and communication,

- Focus on short-term results over long-term impact,

- Inadequate infrastructure and support, and

- Absence of standard academic, experiential, and credential metrics and measurement.

The research identifies that the U.S. emergency and disaster management literature is the most wide-ranging available worldwide. The U.S. is one of the first nations to take preventative measures to solve a local emergency and crisis that became a disaster. This happened when the U.S. government introduced the Congressional Act of 1803. The legislation allowed the government to provide “disaster relief” to Portsmouth, New Hampshire, after a major fire in December 1802.

Emergency Management emerged in the late 1960s, particularly following a series of large-scale natural hazard events (often misidentified as natural disasters). Practitioners adopted “emergency management” to define their event/incident response method. Due to the increasing frequency of natural hazards (formerly known as “natural disasters”) and their destructive effects on communities, emergencies are sometimes referred to as disasters to emphasize the need for significant management and external resources. This initiates ongoing recovery funding (Fletcher and Fletcher, 2007). April 1979 saw the creation of the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), with a desired outcome to better manage emergencies, coordinate federal agencies and provide a civil defense (FEMA, 2021).

To understand the changes over time including the lack of clear definitions of ECDM, varying organizations have introduced their interpretations of the many current language mediums used by the sector. After Action Reviews (AARs) provide a broad range of conflicting views and adoption of applied practice (Royal Commission, 2020.). For consistency, this chapter compares Merriam-Webster and Oxford dictionary definitions to identify the differences in language within Emergency, Crisis, and Disaster Management (Appendix A). According to the definitions, professionalism is a high level of ability or expertise, while credentialing is peer recognition of standard performance. Consistent definitions enable the development of programs that can be universally adopted, leading to an individual’s professional growth. Established and endorsed credential processes form the foundation for professionalization.

FEMA recognizes that a structured approach to building, sustaining, and improving capability is the first step towards ECDM practitioner competency recognition and professionalism. Practitioners must learn and apply the eight emergency management principles—Comprehensive, Progressive, Risk-Driven, Integrated, Collaborative, Coordinated, Flexible, and Professional (FEMA, 2007a, 2007b.)—then demonstrate their competency and capability, qualities which contribute towards attaining a recognized credential. The International Association of Emergency Managers (IAEM) and The International Emergency Management Society (TIEMS) are the only two internationally recognized credential programs that both utilize peer-reviewed credentialing in identifying a practitioner’s fundamental understanding of the principles and practice of Emergency Management (IAEM, 2024; TIEMS, 2024). IAEM and TIEMS both have implemented emergency management-focused credentialing processes. A review in February 2024 of both credentials, the IAEM’s Associate Emergency Manager/Certified Emergency Manager (AEM®/CEM®, introduced in 1993 cites over 3,092 credentialed practitioners and is available for any practitioner to apply. TIEMS introduced its credential process in 2021. The TIEMS Associate Qualification Certification/TIEMS Qualification Certification (TAQC™/TQC™) has awarded 13 credentials as of January 2024, noting that TIEMS membership is an application requirement. Each stakeholder within the ECDM industry must choose which industry association credential that aligns with their organizational standards and practice. As long as issuing groups or professional bodies exist, different regions may recognize and agree on different credentials as being equivalent. In an IAEM 2022 article, Carol Cwiak identified that professional recognition in the U.S. is predicted to take until 2040 (Cwiak, 2022). Gaining global support and recognition may require an additional decade, potentially two, to achieve similar levels of acceptance.

Outside the U.S. there are very few credential programs that are government-supported. As long as issuing groups or professional bodies exist, different regions may recognize and agree on different credentials as being equivalent. TIEMS introduced its credential process in 2021 requiring annual membership renewal to maintain ongoing certification. The Disaster Management Institute of South Africa (DMISA, 2024a), administers the South African Qualifications Authority SAQA. DMISA identifies on their website details of the four SAQA Disaster Management designations (DMISA, 2024c) including: 1). Technician with one current registration, 2). Associate with five current registrations, 3). Practitioner – thirteen current registrations, and 4). Professional – forty-seven current registrations in Disaster Management. Registration and recognition are primarily based on qualifications, employment standing and ongoing membership registration. To maintain registration an individual must undertake Continuous Professional Development (CPD) consisting of twenty (20) credits (DMISA, 2024.) every two years combined with maintaining their membership. Outside of formal qualifications and employment, and subsequent CPD, there appears to be no documented peer review process for verifying the comprehensive emergency management understanding or competency and capability of practitioners.

In summary, ECDM certification systems face growing scrutiny due to a lack of professional recognition linked to remuneration baseline/awards within the industry and government. Whilst the IAEM AEM®/CEM® credential is highly regarded in the U.S., the credential is not always a mandated requirement for a practitioner to gain or maintain employment, nor is the credential linked to a remuneration scale or award. The lack of standard metrics, unclear assessment standards, systemic biases, emphasis on individual achievements, limited communication, short-term results over long-term outcomes, inadequate infrastructure and support, and no formal linkage to remuneration awards contribute to professional recognition issues. Various organizations have introduced their interpretations of the language medium used by the sector, leading to inconsistencies in the definitions of ECDM. As previously stated, FEMA recognizes a structured professional development approach as the first step to ECDM practitioner recognition, while both the IAEM and TIEMS recognize peer-reviewed credentials. Stakeholders in the ECDM industry can still choose which industry association certifications align with their organizational standards and practices.

With this introduction in mind, the following chapter examines international credential offerings and their alignment with Emergency, Crisis, and Disaster Management criteria. Using a qualitative approach, it identifies the U.S. emergency and disaster management literature as the most extensive worldwide. Emerging in the late 1960s, Emergency Management emerged due to increasing natural hazards’ devastating effects. FEMA recognizes structured professional growth as the first step towards ECDM practitioner recognition.

Literature Review

Within the realms of ECDM, there exists a multitude of definitions that differ in their interpretation and application (see Appendix A). It is worth mentioning that the U.S. Merriam-Webster dictionary does not contain meanings for “emergency management,” “crisis management,” or “disaster management.” The authors have adopted FEMA’s definition of “emergency management” while the definitions of “crisis and disaster management” are taken from the Oxford University Press Oxford Dictionary. The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) and several other countries offer alternative definitions of adaptation for each of the three categories. Internationally, the ECDM sector faces a significant problem in determining a universally accepted definition that will serve as the basis for ECDM in working towards the professionalization of the sectors. For clarity and consistency in this chapter the following definitions are applied:

- Emergency Management: the managerial function charged with creating the framework within which communities reduce vulnerability to threats/hazards and cope with disasters (FEMA Definitions, 2022).

- Crisis Management: the process by which a business or other organization deals with a sudden emergency situation (Oxford University Press, 2023b).

- Disaster Management: a comprehensive approach to reducing the adverse impacts of particular disasters, natural or man-made events, which brings together in a disaster plan all of the actions that need to be taken before, during, immediately after, and well after the disaster event. These include mitigation, preparedness, emergency response, recovery, rehabilitation, and reconstruction, also known as emergency management (Oxford University Press, 2024).

The research reveals that there have been limited studies conducted in the general fields of ECDM. Multiple scholarly articles indicate that authors often cite the same research sources, leading to academic duplications with missed opportunities to explore new options based on original discoveries (Gøtzsche, 2021.; Page, Noussair, and Slonim, 2021). Repeated referencing of the same research sources can lead to a rise in a multitude of problems:

- Reiterative observations: Engaging in repetitive exploration of identical terrain consistently overlooks chances for innovative revelations and impedes advancement.

- Narrow viewpoints: Excessive dependence on familiar sources can lead to the omission of valuable alternate perspectives, resulting in blind spots.

- Ineffective knowledge generation: Repetitive research endeavors squander valuable resources that may be allocated to uncharted domains.

Many of the research findings have been generated after major disasters. In 1970, California had a series of terrible fires in its suburban neighborhoods, resulting in damage exceeding $200 million and several fatalities and injuries. During the Californian events/incidents, a collaborative group known as “FIRESCOPE” (Firefighting REsources of Southern California Organized for Potential Emergencies) transformed the traditional oral history of emergency management into an Incident Command System (ICS) (EMSI, 2018) to effectively address future inter-agency difficulties. “FIRESCOPE” is a compilation of the industry’s first comprehensive collection of works, with a consistent emphasis on fire-related issues. However, the majority of the transition from oral history to ICS/emergency management has taken place predominantly in the United States.

The September 2001 World Trade Centre attack (9/11) prompted another shift in how major emergencies that turned into disasters would be handled in the future. Following the events of 9/11, McEntire’s paper (McEntire, 2005) on the state of Disaster Management theory highlighted a significant shift in the field of emergency and disaster management, prompting a full reconsideration of the objectives and essence of disaster management in the United States. The Australasian Inter-service Incident Management System (AIIMS) draws heavily on the U.S. NIMS/ICS systems, enabling multiple international deployments and seamless exchanges during major disasters, reinforcing the importance of foundational and shared emergency and disaster management systems and processes.

With limited options identified when conducting this literature review and while reflecting on current practices that underpin the foundations and importance of education, applied practice, and credentialing (which all contribute towards professionalism), reliance on grey literature has been proven critical. Grey literature includes material that is published informally, non-commercially or remains unpublished. It can take numerous forms, including government reports, conference papers, blogs, non-peer-reviewed articles, and even non-written resources like posters and, infographics (Monash University, 2021). Podcasts and the iAEM Bulletins provide additional resources to these limited cited articles. Many ECDM practitioners have suggested improvements and options to move forward. However, these are mainly personal views, and some are based on experience whilst others remain unsupported.

The findings took into account practitioner concerns, particularly how organisational training and field experience interact with formal qualifications, influencing the impact of emergency and disaster management practice for practitioners and providing evidence leading to credentialing. Certifications can help to support and certify the training and education required to effectively manage emergencies, crises, and disasters. They provide professionals with the ability to organize effective actions that account for volatility and rapidly changing situations.

The transition in emergency and disaster management included improved education and training programs given by numerous U.S. institutions (FEMA.,2024b). The next decade provided professional development opportunities through training programs to help practitioners understand the complexities of emergency and disaster management.

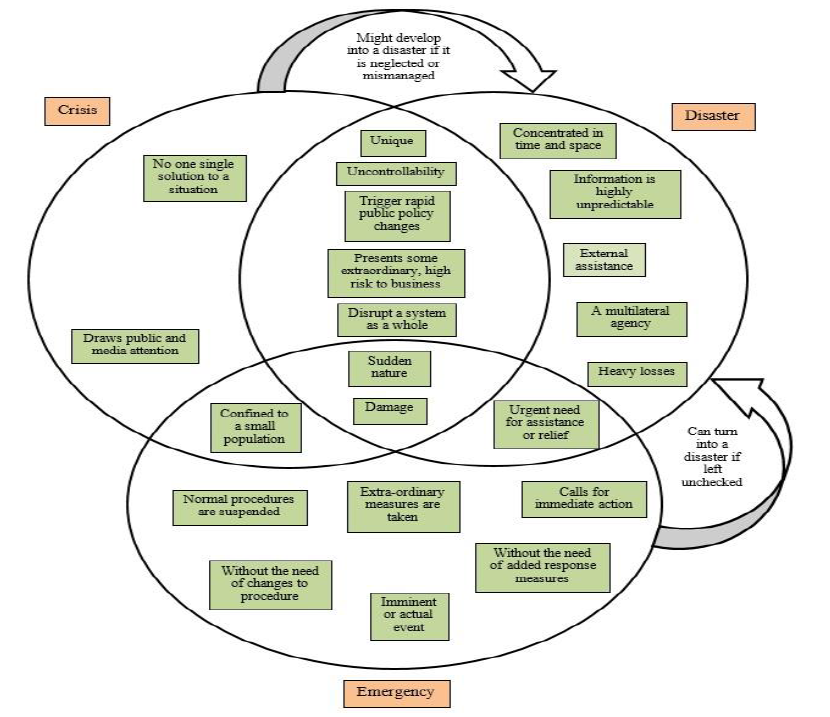

In the article “Understanding the Terminologies: Disaster, Crisis and Emergency” (Al-Dahash, Thayaparan, and Kulatunga, 2016), the authors identify that these three areas are intricate and intersect with each other, identifying overlapping complexities within areas of ECDM. The data obtained by Al-Dahash et.al visually summarize that the incidents are “sudden in nature” and cause “damage” in all three areas.

The distinction is that an emergency is a critical, unexpected, and frequently dangerous event that requires immediate response, whereas a disaster is a sudden accident or natural event that causes significant damage or loss of life. The common aspect of an emergency and crisis is that they are typically limited to a small population (Al-Dahash, Thayaparan, and Kulatunga, 2016)

The relationships between emergency, crisis, and disaster management are highlighted in Figure 1.

These disciplines of Emergency and Disaster Management are not interchangeable, as Figure 1 demonstrates. Although all three ECDM disciplines are engaged in the distinct primary P/E/Cs of Mitigation (Prevention), Preparedness, Response, and Recovery (commonly referred to as PPRR) in the same incident/event, they necessitate various players, and knowledge, and may include a diverse range of stakeholders throughout the different phases. Obtaining an effective conclusion to an Emergency/Crisis/Disaster incident or event involves the participation of each of the disciplines, EM, CM, and DM.

The disciplines include acknowledging the importance and involvement of the numerous stakeholders. Figure 1 identifies that disasters and crises share similar characteristics, such as being unique, and uncontrollable, causing rapid public policy changes, presenting something remarkable, posing a high business risk, and disrupting systems as a whole (Al Dahash et.al., 2016).

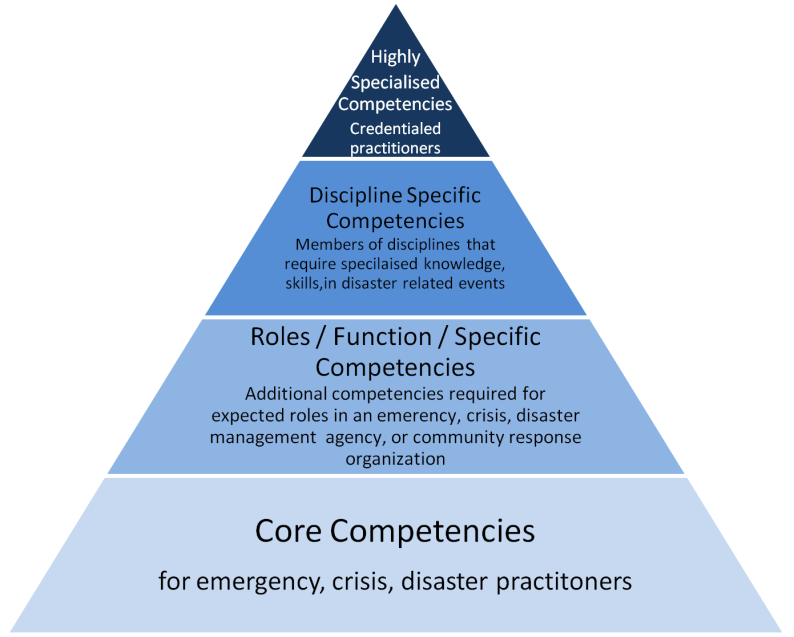

Research of emergency and disaster management stakeholders provided a collection of research published in the American Medical Association Journal in 2011. In the essay, “Core Competencies for Disaster Medical and Public Health” (A. Altman et al. 2012), the authors emphasized that successful planning, response, and recovery in critical situations require a meticulously coordinated endeavor. The coordination of the planning, response, and recovery is required to be headed by experienced individuals who possess specialist knowledge and skills. While certain individuals have received training in this field, others may lack the essential knowledge and expertise necessary to effectively operate under high-pressure catastrophic situations, such as a pandemic. A set of precise training criteria to ensure workforce proficiency for such situations was developed. The skill set development was undertaken by a group of area leaders and experienced practitioners through a series of web-based polls and expert Working Group meetings (A. Altman et al., 2012). The findings were regarded as a promising foundation for delineating the proficiency levels of professionals in the fields of disaster medicine and public health. The competency levels of Emergency and Disaster Management practitioners can be readily aligned, becoming the basis for future research, Figure 2.

There are no delineated and universally agreed frameworks for practitioners to follow in achieving the knowledge, skill, competency as well as the capability needed for ECDM qualifications and certification. Whilst the two national/international associations (IAEM & TIEMS) have implemented their visions of EM credentialing, there are differences between the two. The authors acknowledge that in the U.S., there exist multiple state certification programs that prioritize recognition of their credentials over international ones. In both the IAEM and TIEMS credential programs, State credential certifications are accepted as a contribution component but not equivalent to the respective IEAM/TIEMS credentials. Additional research is required to identify the gaps between individual State and IAEM/TIEMS certification programs.

That being said, the FEMA publication “Emergency Management: – Definition Vision Mission Principles” lays the groundwork for emergency management (FEMA, 2007a). It defines key concepts for the field:

- Definition: Emergency management is the managerial function charged with creating the framework within which communities reduce vulnerability to hazards and cope with disasters.

- Vision: Emergency management seeks to promote safer, less vulnerable communities with the capacity to cope with hazards and disasters.

- Mission: Emergency Management protects communities by coordinating and integrating all activities necessary to build, sustain, and improve the capability to mitigate against, prepare for, respond to, and recover from threatened or actual natural disasters* (hazards), acts of terrorism, or other man-made disasters.

- Principles: Comprehensive, progressive, risk-driven, integrated, collaborative, coordinated, flexible and professional.

- NOTE: * Current practice and understanding redefines “natural disasters” now as natural hazards – “Disaster = hazard exposure vulnerability” (UNDRR, 2023.; UNDRR, 2024).

In addition, Feldmann-Jensen researched the “Next Generation Core Competencies for Emergency Management Professionals’’ (Feldmann-Jensen, Jensen, and Smith, 2017) for the FEMA Higher Education Program in 2017. The research proposed a future for a Disaster Risk Management (DRM) workforce must align with the Sendai framework and be consistent with approaches across communities, civil society, and business. Successful DRM relies on understanding governance, policy, and collaboration across communities. Core competencies are crucial for developing successful future DRM practice, as they unify a diverse workforce. A Next Generation Core Competency framework for DRM professionals was developed in 2016-2017, offering broad, local, and global application options. These competencies can be used across various emergency services sectors, such as DRM, humanitarian assistance, public health preparedness, fire, law enforcement, and counter-terrorism (Feldmann-Jensen, Jensen, and Smith, 2017).

Core competencies of communal learning ideas which align in principle with the work undertaken by A. Altman et al. in 2012 should be integrated into the higher education curriculum to ensure consistency of learning and robustness of practice within accredited qualifications. In the vocational education environment, experiential learning is combined with FEMA Independent Study courses and programs offered by vocational institutions like Frederick Community College (FCC, 2024a) incorporating the Mid-Atlantic Centre for Emergency Management & Public Safety programs (MACEM&PS)(FCC, 2024b). The research identified that Emergency Managers are predominantly required to acquire knowledge and skills in emergency management through self-learning. The missing linkage in the ECDM recognition is a vocational education-based on the ‘’Next Generation Core Competencies for Emergency Management Professionals” body of work utilizing the same structure as the Feldman-Jensen 2017 research which would ensure that both academic and vocational learning are aligned to common agreed learning outcomes.

Published at the same time as the Feldmann-Jensen 2017 paper, Dudley McArdle completed an extensive study on Australia’s Emergency Managers (McArdle, 2017), which revealed the presence of numerous deficiencies in the Australian Emergency & Disaster Management sector. McArdle recognized one of the inadequacies being the failure of sector leaders in their professional obligations as well as their shared responsibility across agencies, governments, and emergency managers to take decisive action that promotes disaster and community resilience. For a profession to gain recognition and be considered a legitimate vocation, positions must be connected to accredited education and receive appropriate remuneration within the professional field. The existing recognition methods in Australia indicate a deficiency in maturity, as the Emergency Management practice is currently defined as an Administrative Officer positional role/job description, open to applicants without consideration of qualifications. To be recognized as a professional, job descriptions need a certain accredited qualification for each position. By establishing connections to recognized accredited qualifications and referring to a detailed description of a Professional Officer position, the sector can guarantee the advancement of the industry in terms of quality. It is important to acknowledge that remuneration packages for administrative and professional award levels are frequently comparable or slightly elevated in certain cases.

In 2017, FitzGerald (Fitzgerald et. al., 2017) represented eleven Australian Universities to develop The Generic Emergency and Disaster Management Standards (GEDMS) through a mixed qualitative research approach involving a systematic literature review and mapping of current academic Emergency Management course content offered in Australia and New Zealand. GEDEMS set down a Standard for Emergency and Disaster Management based on knowledge, skills, and application.

The standards recommended included:

1. The three main themes within the knowledge domain:

Governance and policy frameworks

Theoretical and conceptual basis for practice

Contemporary disaster management

2. The three main themes within the skills domain:

Leadership

Communication

Collaboration

3. The two main themes from the application domain:

Professional Practice

Critical thinking

Another Australian, Russell Dippy, authored an opinion paper titled “Professionalism: certification for emergency managers” (Dippy, 2020) in the Australian Journal of Emergency Management (AJEM). Dippy determined that although Australian emergency management has made some efforts to enhance the level of professionalism, there is evidence that demonstrates that individual certification plays a crucial role in fostering professionalism. The recognition of accreditation for individuals in the field of emergency management in Australia has not been extensively acknowledged. Emergency Management professionals should pursue certification (Dippy, 2020) which is viewed as a component of their continuous professional growth and mechanism for maintaining currency of knowledge and skills.

More recently, Australian Haydn McComas undertook a Churchill Scholarship in 2022, “Fire and Emergency Service Leadership: Fact or Fiction” (McComas, 2023). In his report, he identified several Emergency Service leadership development programs internationally. A long-standing defense-based initiative emerged from Denmark managed through the Danish Defense Force in which the concept and components could be adapted to support ECDM professional development either regionally or globally.

Carol Cwiak’s February 2022 IAEM Bulletin article, ‘Forging our Path: Emergency Management’s Pathway to Power’ (Cwiak, 2022), presents a U.S. professionalization pathway for emergency management from the present to 2040. The article discusses emergency and disaster management expertise from U.S. Subject Matter Experts. “The Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct for Emergency Management Professionals” (the Code) (FEMA HEP, 2021) is being reviewed by the FEMA Ethics Special Interest Group (SIG ) (FEMA/EMI, 2022). The foundations of the Code are sound, yet Emergency and Disaster Management definitions are missing and Crisis Management not gaining a mention. Yet all three disciplines are interrelated with important linkages (refer back to Figure 1). The authors conclude that without an international consensus on the component definitions, grouping them under “emergency management” is insufficient to standardize and internationalize ECDM credentials leading to professionalization.

Methodology

This chapter was developed using a qualitative methodology utilizing action research, a research method that aims to simultaneously investigate and solve an issue. Action research is often reflected in 3 action research models: operational (sometimes called technical); collaboration; and critical reflection (Georg, 2024). Incorporated resources included global organizations, agencies, and associations. The sources used for this research included academic papers, searches on Google Scholar and Semantic Scholar, information from the FEMA/EMI Higher Education Program, details about organizational and state certification programs, and definitions from the Oxford Dictionary. Other sources included:

- ELSEVIER,

- Taylor & Francis Online,

- ERIC – Institute of Educational Sciences,

- United Nations Office of Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR),

- Sage Journals,

- Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness,

- International Association of Emergency Managers Bulletins,

- Journal of Emergency Management,

- The Australian Journal of Emergency Management,

- Higher Education Thesis submissions on Emergency Management guidelines, course material, and government policies,

- Royal Commissions,

- After Action Reviews, and

- grey literature from various blog sources.

The overarching emergency management organizations encompass, amongst others, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in the United States; the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA-NZ) in New Zealand; the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA-AU) in Australia; and the Disaster Management Institute (DMISA) in South Africa. The inter-relationships between associations, organizations, and emergency and disaster management practitioners have resulted in differing language interpretations (Holley A and McArthur T., 2022) and continue to be a significant concern, highlighted in the recommendations of the Australian Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements released in October 2020 (Royal Commission, 2020).

A comparative analysis by the authors was undertaken to evaluate available certification options to international practitioners. Whilst there were some credentialing programs identified, most were country or state-specific with only two programs being open to international practitioners. The IAEM Associate Emergency Manager/Certified Emergency Manager (AEM®/CEM®) and the TIEMS Associate Qualification Certification/ TIEMS Qualification Certification (TAQC™/TQC™), are available to international practitioners. The purpose of the comparison analysis was to evaluate the merits and drawbacks of these two existing programs concerning the principles and practices of comprehensive emergency management across the four main P/E/C of PPRR. The idea of defining terminology is sometimes misunderstood; “comprehensive Emergency and Disaster Management experience” (IAEM, 2024b) where:

Comprehensive Emergency Management means integrating all actors, in all phases of emergency activity, for all types of disasters. The ‘comprehensive’ aspect of Comprehensive Emergency Management includes four phases of disaster activity: mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery for all hazards—human-caused (accidental and intentional), technologically-caused (accidental and intentional), and natural—in a federal, state, local operating partnership.

A comprehensive examination of the methodologies employed in each certification credentialing system was undertaken. This was accomplished by using a table to discover similarities and variations, to prevent any potential bias towards a particular program. A subsequent examination was undertaken to ascertain the alignment patterns between the educational qualification curricula that correspond to PPRR and the Domains of Generic Emergency and Disaster Management Standards, as seen in Figure 3, within the two international credentialing procedures. Each certificate employs distinct methodologies in its examination assessment and review criteria. Both processes cannot be compared or confirmed because they are proprietary. Both parties will assert that the assessments are “all-encompassing” and suitable for industry use. There is no autonomous entity that can verify the claims made by each association.

The purpose was to investigate essential aspects of ECDM and their relationship to the challenges and concerns experienced during certification and professionalization. This study aimed to explore the impact of change on organizational cultures, systems, processes, institutional recognition, and government legislation hurdles in a global context.

Findings and Solutions

Our analysis reveals that the interconnections among the disciplines of emergency, crisis, and disaster management are intricate and frequently lack clarity. Practitioners also face difficulties in comprehending the complexities of the Emergency Management Continuum, the Disaster Management Continuum, and the Disaster Risk Reduction Components, as well as their interconnections. Adding to this problem is the lack of consistency in the available choices for education and professional growth in these fields. Indeed, several countries lack the provision of professional development programs for practitioners in the field of Emergency, Crisis, and Disaster Management (ECDM). Moreover, it can be a difficult undertaking to establish connections between these programs and the necessary certificates or credentials. The purpose of this introduction paragraph is to clarify these concerns and emphasize the necessity for enhanced comprehension and education in the domain of ECDM.

Comprehension of the ECDM domains and the primary P/E/Cs of PPRR is crucial for efficient actions during disruptive incidents. The relationship between EM, CM, and DM is complex, and establishing a uniform sector baseline is challenging and non-existent.

For instance, the U.S. has 280 higher education institutions providing over 500 degrees and certificates in ECDM. However, there is an inconsistency between qualifications and no widely recognized vocational pathways for practitioners. The draft U.S. FEMA Ethics Special Interest Group’s Code of Ethics and Conduct for Emergency Management Professionals adds new hurdles to achieving recognition.

Australia, while offering five Public Safety Diplomas/Advanced Diplomas and one Graduate Diploma, with two Recovery Management qualifications developed in 2020, remain predominantly unrecognized within the industry. The Australian Government – Job Skills Australia agency identifies the Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO), but ECDM is not mentioned nor recognized in the classifications.

In Asia, there are limited professional development programs for emergency and disaster management, with training primarily focused on Urban Search and Rescue (USAR). Understanding the ECDM domains as per Figure 1 and the primary P/E/Cs of PPRR is essential for efficient actions during disruptive incidents/events to make and distribute critical decisions (Carter, 2008; Coppola, 2006). The Prevention, Preparedness, Response, and Recovery (PPRR) concept is crucial to current Emergency, Crisis, and Disaster Management (ECDM). However, the focus is frequently on the “Response” component and analyzing incident or event consequences. Social media has greatly impacted incident management, highlighting this focus. Decision-makers and responders are now monitored in real-time by the community. Thus, a new class of “armchair critics” can instantly comment on and analyze responders’ actions. This makes emergency management certification even more important. It trains practitioners in both technical emergency response and social dynamics from platforms like social media. ECDM will be more effective if a well-credentialed practitioner can handle these issues.

The transition into short-term Recovery (weeks – to six months) is often overlooked and handed over to another agency. Medium-term (months–two years), and long-term (years – decades) recovery presents more challenges in maintaining continuity of communications and recovery services. Mitigation (Prevention) and Preparedness are often incorporated into credentialing programs, however in practice whilst closely related are often overlooked because they rely largely on funding in economically pressured environments. FEMA has produced a guide on Disaster Financial Management (FEMA, 2020), which provides examples for communities who have limited revenue streams and guides towards seeking financial assistance to support recovery from disaster events. Whilst U.S.-centric, it provides an example of another administrative complexity an emergency manager must contend with.

Additionally, a thorough understanding of the basic concepts, nomenclature, and application of practice is needed to create consistent and effective professional skills and educational programs in ECDM by Institutions, government bodies, specialist focus groups, and credential working groups. Current programs do not provide sufficient learning opportunities that ensure a comprehensive overarching understanding of all the P/E/C of ECDM. ECDM basics require education, exploration, and ongoing knowledge updates throughout the four primary P/E/C of PPRR. To establish ECDM as a profession, mentorship, and practitioner certification are essential (Cwiak, 2022) to ensure consistency across the ECDM industry.

The relationships between EM, CM, and DM are not well explained in the literature. The key challenges include developing common definitions for ECDM, as well as establishing important criteria for adopting a uniform sector baseline across all three domains (Al-Dahash, Thayaparan, and Kulatunga, 2016). As there are so many governments, agencies, organizations, and institutions in the U.S. sector alone (each with its influence and perspective), it is unlikely that a uniform set of criteria will meet the needs of the majority of organizations requiring government intervention.

The draft U.S. FEMA Ethics Special Interest Group (SIG)(FEMA/EMI, 2022) “Code of Ethics and Conduct for Emergency Management Professionals” (the Code), while providing a sound foundation document, adds new hurdles to achieving recognition as a profession within the U.S. Expanding the Code to include universal acceptance is potentially unlikely. Acceptance may be improbable because of the disparities in cultural, social, educational, and application standards that exist across different jurisdictions, states, nations, and worldwide regions, both in applied practice and education. Aligning any disparate accrediting systems into a globally acceptable recognition will pose considerable hurdles for any future registration authority.

The largest association may be given primacy, allowing its registration nation to set educational standards, making regional and international educational norms and practical implementation difficult. Jurisdictional governments, country, state, national, and global regions frequently adopt their own emergency and disaster management methods in the absence of standardized conventions. Stakeholders believe their method is efficient and tailored specifically to their business. The U.S., having the largest number of practitioners and schools, will most likely set the standard for this complex system noting three considerations:

- It is likely that cultural and traditional differences can pose challenges, but they can also offer opportunities for enrichment and growth if leveraged appropriately.

- It remains to be seen which country will emerge as the host for a global credit institution (i.e. an NGO/Not for Profit which is not affiliated to any institution, association, or country).

- It is expected that the standards will process autonomous capabilities and demonstrate a high level of reliability.

An inherent drawback of a U.S. regime will be the requirement for gaining consensus on criteria and standards amongst states, counties, and agencies due to the fact many practitioners have significant influence owing to experiential background, local residence, and work in local or state agencies. The current situation is anticipated to endure for a minimum of 20 years (Cwiak, 2022). Refer to Appendix B for the list of the Countries and Organizations reviewed in Emergency and Disaster Management referencing for this chapter.

Pathway to Professionalism

Existing professional organizations and registration bodies recognize the need for an accredited undergraduate degree for general professional registration. Industrial frameworks make qualification recognition essential for new practitioners who require an undergraduate degree to succeed professionally. For non-degree and vocational professionals to achieve recognition without qualification, the Australian Advanced Diploma and U.S. Associate Degree graduates could complete the Bachelor’s requirement through the vocational program inclusive of experience of potentially two years plus a Graduate Certificate. Successful vocational training requires a nationally and internationally recognized curriculum that can be contextualized to country-specific and local situations with progressive pathways to accredited qualification recognition. Recognizing the unique characteristics of Emergency Management Higher & Vocational Education and varying training programs allows us to delve into a comparative analysis, highlighting how these differ across various countries, noting some regions do not offer any acknowledged professional development in ECDM.

North America – United States

U.S. higher education has over two-hundred and eighty (280) institutions (FEMA, 2024b). These schools provide over 500 two-year, four-year, and higher education degrees and certificates. From the pool of 500, the authors reviewed 50 institutions at random, and whilst many have similar name conventions, many varied significantly in their curriculum outlines, noting the published curriculum often did not match the four basic Phases/Elements/Components (P/E/Cs) of PPRR. For instance, there were no widely recognized vocational pathways identified for ECDM practitioners, noting that college credits (vocational) may be used to gain entry and continue with emergency management study within higher education, however, there were no consistent college credits listed. In addition, state-based initiatives in the U.S. credential programs are not well recognized within the global credential environment. Many U.S. states require state-based credentials for practitioners seeking employment as these local credentials prioritize the specific needs and conditions of their respective states and local areas.

There are only two worldwide credentialing programs identified, namely the IAEM AEM®/CEM®, U.S. based and TIEMS TAQC™/TQC™ out of Europe but servicing the U.S. market, noting they are similar but not identical. The IAEM AEM®/CEM® and TIEMS TAQC™/TQC™ credential programs do not evaluate an individual’s comprehensive knowledge of emergency management across all four P/E/C of PPRR complexities. Each program claims to evaluate a thorough understanding of comprehensive emergency management experience (IAEM, 2024b, 7; TIEMS, 2024). The U.S. as a global leader in education and professional development include the “U.S. FEMA/EMI Higher Education Program” Certifications and Academic & Training Courses (FEMA, 2024b).

North America – Canada

In February 2024, expressions of interest in Canada requested feedback for the creation of a nationwide civil response capability (Public Safety Canada, 2024.). Analysis indicates that a call for submissions identified that Canadian professional development opportunities within the ECDM environments are limited to ensuring a sufficient level of qualified personnel undertake current roles and responsibilities.

The Justice Institute of British Columbia (JIBC) offers an online Associate Certificate that can be upgraded to a Diploma, Degree, or Post Graduate Diploma. Emergency Management programs at Royal Roads University in British Columbia include degrees, graduate diplomas, and master’s degrees. There are other programs at York University. Given the limited number of education providers and lack of a national credentialing framework, building a quick-deployable resource remains possible (Public Safety Canada, 2024). The Canadian IAEM AEM®/CEM® program is trusted and provides one recognition pathway.

Oceania – Australia

The Australian vocational education system offers five Public Safety Diplomas/Advanced Diplomas and one Graduate Diploma (TGA, 2023a). Included in the suite of qualifications, two Recovery Management qualifications were developed in 2020 with the AQF Level 5 Diploma (TGA, 2023b) released in December 2022 with the AQF Level 6 Advanced Diploma currently awaiting release. International research reviewed seven countries’ emergency and recovery management courses and certificates. The Australian Government received the final National Recovery Training Program: International Benchmark Report (Ainsworth, 2021), which revealed few commonalities between international courses other than names, with no specialized recovery qualification identified within U.S. institutions (FEMA, 2024b). Currently, Australia is the only country that has an accredited Recovery qualification that fulfills the requirements of the P/E/C Recovery period following a large event. Recovery efforts can be ongoing for a decade or more, raising concerns throughout the sector about professional growth, practitioner aptitude, and proficiency in this key area.

Australia’s fire and emergency services sector relies heavily on competent and capable volunteers. This is achieved through compulsory vocational training to respond effectively. Australian and New Zealand National Council for Fire and Emergency Services (AFAC) member organizations engage over 250,000 volunteers or 87% of the sector’s capability. At the AFAC21 conference, Bartlett reported that 78% of the 80,000 people who responded to the 2019-20 bushfires were qualified and experienced volunteers, emphasizing the Australian reliance on volunteers in emergency operations. (Bartlett, 2021, p. 3)

Volunteers in Emergency Services organizations in Australia require operatives to have completed Australian Quality Framework (AQF) accredited qualification and agency training programs prior to being deployed operationally. Public Safety Training (PST) includes Emergency Service qualifications. PST provides thirty-two (32) Emergency Service sector certificates in Fire, State Emergency Service, and community safety sectors. In the area of Emergency and Recovery Management, there are three AQF Level 5 Diplomas, two AQF Level 6 Advanced Diplomas (equal to US Associate Degrees), and an AQF Level 8 Post-Graduate Diploma (TGA, 2024). Industry-specific first responders, emergency, crisis, and mid-management are delivered by Registered Training Organizations (RTOs) using the same qualification. Competency units are easily adaptable to local conditions and within international contexts.

The Australian Government – Job Skills Australia Agency, identifies the Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO) and lists the classification definitions based on the skill level and specialization usually necessary to perform the tasks of the specific occupation, or most occupations in the group. The emergency management system in Australia is a shared responsibility between the Government-appointed body National Emergency Management Agency, state governments, and local government. The organization states that “We coordinate efforts to respond to and recover from disasters and emergencies. We lead the Australian Government’s disaster and emergency management response. We work to build a disaster-resilient Australia that prepares and responds to disasters and emergencies” (Department of Home Affairs, 2023). The disconnect within ECDM is in the ANZSCO classifications where ECDM is neither mentioned nor recognized (Australian Bureau of Statistic, 2023). Australian Emergency, Crisis, and Disaster Managers are relegated to administrative roles, responsibilities, and positions. Qualifications remain professionally unrecognized within the Australian industry sector.

Oceania – New Zealand

Similar to Australia, New Zealand provides a range of emergency management vocational certificates managed through the New Zealand Qualifications Authority (NZQA) which are primarily response-focused. If a practitioner desires to build expertise and gain a recognized qualification, Auckland and the University of Canterbury and Auckland University of Technology both provide undergraduate Bachelor qualifications. Massey University delivers Bachelor’s and Master’s degree programs which will contribute towards a professionalization pathway.

Asia

Asian countries provide very limited emergency and disaster management accredited professional development programs, relying on professional organisations to fill this void. The predominance of emergency and disaster management training is conducted within the various emergency response services and operationally focused, particularly in the specialized area of Urban Search and rescue (USAR). The primary organization providing Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) is the Asia Disaster Reduction Centre (ADRC) (ADRC, 2024a), headquartered in Japan. The center represents 32 countries with its membership primarily focused on fostering the development of a multilateral network to increase DRR capability in Asia. This includes facilitating exchanges of DRR-related individuals. ADRC does not provide credentialing pathways or recognition for individuals. ADRC is supported by Australia, France, New Zealand, Switzerland, and the United States (ADRC, 2024b). There is little or no evidence of any ECDM professionalization programs. However, supporting countries that deliver recognized ECDM university programs has the potential to provide a professional development pathway for individuals.

Japan

Japan is primarily a community-led emergency response culture. It stems as far back as the 17th century (Suibo-dan for flood risk), 18th century (Syobo-dan, volunteer Fire Corps for firefighting), and 1970s (Jisyobo for earthquake disasters). Each of these is supported through legal acts (Shaw, Ishiwatari, and Arnold, no date). Japanese community-led programs remain still in place today, form the backbone of local public-level non-emergency service responses. Disaster response capabilities, targeting municipal, prefectural, and government officials in Japan, are facilitated through the Disaster Management Training Center (DMTC) within the University of Tokyo (University of Tokyo 2021). DMTC researches, develops and standardizes disaster management training and education systems suitable for Japan.

No EDCM professional development programs were readily identified, although they likely exist in one form or another. However, the Japanese Cabinet Office designs and promotes the Basic Disaster Management Plan and emergency plans. Other agencies include the Fire and Disaster Management Agency (FDMA) (FDMA, 2024.), which does not directly supervise or operate local municipal departments. FDMA owns and maintains fire engines, helicopters, and other auxiliary vehicles used by departments nationwide. Their services include training, coaching, and help for all departments (FDMA, 2024).

United Kingdom

In the U.K., there is an ongoing debate on the concept of “risk owners” in the field of emergency management, which is sometimes referred to as “civil protection.” This term has often been interpreted as an expansion of the responsibilities typically associated with the fire service. The most closely related field to ECDM is the Business Continuity qualifications, which are widely implemented in the U.K. The Emergency Planning College is owned by the U.K. Cabinet Office (EPC, 2024). The College is the national center for resilience, learning, and development, provision of training, exercising, and consultancy services to organizations in the U.K. and around the world. The center is managed on behalf of the Cabinet Office by Serco Ltd (EPC, 2024). No structured ECDM professional development qualifications were identified.

Other European Countries

Emergency management in Europe exhibits a notable deficiency in maturity. The main activity is undertaken by the European Response Coordination Center (ERCC, 2024). In most European countries, emergency management, sometimes known as “civil protection”, and much like in the U.K. has traditionally been seen as an extension of the fire service. The disaster management systems of France and Italy are widely regarded as the most superior in Europe. It was only after the November 2015 Bataclan terrorist attacks that France realized the importance of adopting a comprehensive approach to emergency management. Most European countries defer their ECDM roles and responsibilities to their respective emergency service agencies. Every country has its unique approach and strongly protects its sovereignty in this area. To date, no instance of a pan-European credential being implemented for emergency management could be identified.

No EDCM professional development programs were readily identified other than the TIEMS Certification program. In his scholarship report, McComas identifies the values of the Danish Emergency Management Agency (DEMA) system (McComas, 2023, pp. 49 – 53). The Danes recruit five-hundred (500) conscripts every nine months through the parent organization the Danish Ministry of Defense. Many ex-DEMA conscripts are sought after and join the Danish fire services. McComas summarizes that leveraging its position within the Danish Defense Ministry, DEMA allows the Danish national government to support local and regional emergency services quickly and effectively without taking over. DEMA enables Denmark to coordinate and deploy specialized international emergency aid without using the Danish Defence Force. In addition, Denmark’s national government’s large investment in emergency service leadership development shows a clear commitment to success. Given the lack of internships offered by worldwide Emergency Management agencies, this framework offers potential opportunities for professional growth and enhanced capacity. By engaging in further overseas study, individuals can enhance their credentials and strengthen their candidature for any recognised certificate.

Options

As can be seen, different institutions and countries stress local context and cultural norms; hence degree certifications vary. Colleges and universities award undergraduate degrees after three to six years, depending on the institution and discipline. U.S. Bachelor’s degrees require four years, but the U.K., Europe, Australia, and New Zealand take three years plus a fourth year for Honors. The differences make global certification and qualification standardization challenging. The challenge arises in mapping and navigating a professional development pathway through qualification Level 5 (Diploma), Level 6 (Advanced Diploma/Associate Degree), and Level 7 Bachelor qualifications where transition becomes problematic (AQF, 2013).

AQF Emergency Management qualifications were based on global course styles and local needs. Final products were tailored to national sector-specific audiences which allowed for local contextualization. The respective AQF qualifications ensure global context and transferability of knowledge and skills are maintained. As an example, regular international exchanges of senior operational Incident Management Teams (IMTs). Exchanges between Australia and North America during catastrophic fires demonstrate Australian professional development and qualification excellence. In 2022-23, 49 Victorian firefighters and emergency services professionals fought wildfires in Alberta and British Columbia with 200 Australian and New Zealand National Council for fire and emergency services (AFAC) responders from Australian and New Zealand. Australia and New Zealand sent five combined deployments of firefighters to North America in 2022-2023 (EMV, 2023) to assist with the wildland fires. With a majority of Incident Management Team operatives requiring recognized training to be considered for such deployments, combined with the unique experience of overseas operational experience is a strong contributor to any credentialing application.

Many Australian firefighters and State Emergency Services volunteers work for multiple agencies at the commencement of their careers. The commonality of AQF II-IV qualifications in Public Safety provides for sector-wide recognition of knowledge, skill, and competency. Midstream course recognition does readily transfer between AQF and higher education. Graduates struggle with course structures, transferability, and recognition of previous studies due to institutional and program differences. Various training providers struggle to map course content between programs, with experts recommending students start similar courses again, which involves additional fees. Course mapping credits may result in units with similar qualifications being recognized and credited, however, decided by the individual institution. To meet global standards, Australia’s vocational to global higher education qualification transfers must be rigorously scrutinized. Higher education transitions are difficult because each school has its specialties to satisfy local needs. Emerging U.S. standards (Cwiak, 2022) could offer a consistent credentialing framework that permits people to study at many national and international institutions and earn nationally and globally recognized degrees. If required to recognize a student’s previous ECDM coursework, several colleges may cut emergency and disaster management programs owing to reduced financial returns.

On request from the Australian Government, the author, Christopher Ainsworth, produced a foundation report for a streamlined emergency and disaster management professional development and educational pathway in November 2023 (Ainsworth, 2023). The Australian National Emergency and Disaster Management core curriculum was proposed and accepted by training.gov.au, initially published as PUA00 – Public Safety introduced in 2000. The Public Safety Training Package has been continually updated through to the current PUA – Public Safety (Release 5), distributed in December 2022 for all approved training providers and institutions. Open Universities Australia (OUA), an online higher education company, partnering with 25 Australian universities offers multiple accredited degree and post-graduate qualifications. OUA provides opportunities for universities to deliver multi-university optional degrees (OUA, 2024). Practitioners could commence with a common core from a university of choice and electives from many partner universities that fit their primary position or prepare them for organizational advancement. Any new accrediting agencies could recognize emergency management qualifications internationally based on industry stakeholder consistency.

The foundations of learning are through experience and education in preparing practitioners to undertake their roles and responsibilities efficiently and effectively. As a practitioner’s competency and capability increase, the next verification level is credentialing. Experience and education are embedded into each of the credentialing programs listed below, using peer recognition to evaluate an applicant’s submission. The industry’s main issue is uniting international stakeholders to agree on a minimum standard, potentially blending education and experience. Educational qualifications rarely cover all four P/E/Cs of PPRR, noting that an applicant’s demonstration of a comprehensive understanding is not evidenced within either credential as defined in the IAEM guidebook; “comprehensive Emergency and Disaster Management experience.” (IAEM, 2024b, p. 7).

A notable disparity exists within the domain of training and professional development. The AEM®/CEM® certification necessitates the completion of a total of 200 hours, comprising 100 hours of Emergency Management and 100 hours of General Management. These hours must be completed within the preceding decade. A minimum of 50 hours of Emergency/Disaster Management training must be completed within the past 5 years to meet the TAQC™/TAC™ requirement. The analysis demonstrates a notable disparity in the criteria for training and professional development. During the five-year recertification, the gap decreases dramatically, while the AEM®/CEM® maintains a higher requirement.

Westbrook’s 2021 dissertation, (Westbrook, 2021) highlights the challenges faced in delivering state-based and multi-level emergency management training. The dissertation highlighted the inadequacy of the U.S. Georgia Emergency Management Certification Program (GACEMP) in preparing students and practitioners for their local emergency management roles. The foundation of this state-based program is mostly derived from FEMA Independent Studies, supplemented by instructor-led courses.

Instructor competency was an incidental finding that established an unexpected but important theme to the findings of this study. According to participants, the instructors’ lack of extensive knowledge of the topic and experience in the topic at the local level reduced the curriculum’s effectiveness. Participants were outspoken concerning their displeasure with the competency of some instructors who delivered various courses within the GACEMP required curriculum. (GEMA/HS, 2021, p. 94)

This dissertation highlights the challenges faced by all stakeholders without offering a current solution, causing difficulties for many in the sector to determine the most suitable options for practitioners. Whilst the GACEMP program was the only program identified during the literature review and research, there is a strong probability that many state-based credential systems experience similar challenges. Westbrook’s dissertation should not undermine the significance and contributions of state-based programs. The process of ECDM is continuous and cyclical, with no definitive finish. Implementing a Lessons Management Framework in all credential-based programs allows for the continuous critical evaluation of the program. This enables necessary adjustments, modifications, or introductions of new aspects based on ongoing discoveries and insights. Nevertheless, these are the challenges for leadership to continually improve programs to maintain their currency and strength. The findings highlight the importance of ongoing professional development for practitioners and leaders to continually improve their knowledge, skills, and competencies. Every program manager must recognize the significance of incorporating a Lessons Management Framework into their programs.

Discussion

The effectiveness of credentialing systems is dependent on the excellence of educational programs and the level of experiential learning they offer. These arrangements are additionally reinforced by the implementation of Vocational Education programs, which provide hands-on skills and knowledge for a diverse array of professions. Credentialing is essential in this process since it guarantees that individuals possess the necessary qualifications and expertise in their respective specialist areas. Each of these components listed below contributes to the overall objective of striving for professionalism, hence improving the quality and credibility of the workforce.

Education Programs

Sound credentialing arrangements are underpinned by quality education programs and experience. Our research shows that the ECDM global industry sector is highly fragmented, identifying that the U.S. dominates practitioner engagement and the U.S. and Australia dominate educational and professional development opportunities. Australia leads at the early practitioner level through facilitated learning in the Australian Public Safety Training (TGA, 2024.) and the U.S. in the higher education environment (FEMA, 2024b). The ECDM industry’s biggest challenge will be to agree on a global benchmark for credentialing accreditation which includes educational standing that leads to the professionalization of ECDM. With the coming-of-age of the ECDM industry, now may be the appropriate time to separate EM and DM (Figure 5). Emergency Management, which is predominately within the area of Emergency Services roles and responsibility of Response/relief. Disaster Management falls within the areas of Mitigation (Prevention), Preparedness, and Recovery (PPRR) in which multiple services are delivered over extended timeframes often 5 years to a decade or longer. Dividing EM and DM will potentially enhance practitioner comprehension and understanding whilst acknowledging the difficulties in defining roles and responsibilities in each of the areas. This division of domains can be fulfilled without impacting existing professional development programs and employment opportunities.

Education programs must comprehensively include at least the four primary areas of the PPRR to ECDM to ensure that sound knowledge underpins applied practice. To preserve the ECDM industry standardization, all qualifications must be equally assessed through National Qualification Frameworks (AQF. 2013.) as applied in Australia. The practitioner credentialing process must prioritize PPRR implementation, supported by globally agreed educational qualifications, as a key component for certifying any agreed credentialing system/s.

Supporting Vocational Education Programs

Australia leads in the Public Safety vocational education space with thirty-two (32) recognized qualifications (TGA, 2024), from Certificate Level 2 to Level 4, that emphasize the underpinning technical skills for entry-level practitioners. These qualifications provide the necessary information, ability, and expertise needed to pursue the Level 5 (AQF Level 5) Diploma and Level 6 (AQF Level 6) Advanced Diploma (equivalent to a U.S. Associate Degree) in Emergency Management. Australian registered Training Organizations (RTOs) are required to implement each qualification’s unit structure which ensures consistent assessment outcomes. In the U.S., FEMA lists 47 U.S. Community-Based Colleges offering 81 certificates (FEMA, 2024b), 40 provide graduates with an Associate qualification, whilst 41 certificate courses are directed at various specialized areas. Many of the certificate courses used by the U.S. Colleges rely on FEMA Independent Study as the mechanism for assessment. Comparison and assessment of any qualifications is difficult without a nationally recognized assessment standard, noting currently the U.S. does not have a National Qualifications Framework (NQF) (USQF, 2024). Considering these discrepancies the following recommendations lay the first building blocks towards the final goal of professionalization.

Supporting Higher Education Programs

FEMA’s college list (FEMA, 2024b) identifies U.S. higher education dominance in the ECDM environment. Multiple U.S. qualifications have identical names, but a sampling of the course layouts highlighted that the programs varied widely. Qualitative comparisons are difficult for experienced educators due to the misalignments. A similar issue exists for several sector-level higher education qualifications globally. The 2017 Feldmann-Jensen et al. study “The Next Generation Core Competencies for Emergency Management Professionals: Handbook of Behavioral Anchors and Key Actions for Measurement” drafted emergency management competencies for 2030 and beyond.

- Recommendation 1: Vocational Advanced Diploma/Associate Degree graduates be provided a recognized pathway opportunity to transition to an academic stream to complete the final one-year (of a three-year) or two-year (of a four-year) Bachelor’s Degree program equivalence.

- Recommendation 2: The established and proven Australian Quality Framework (AQF) vocational AQF Level 5 Diploma in Public Safety Emergency Management, Recovery Management, AQF Level 6 Advanced Diploma in Public Safety Emergency Management, and AQF Level 8 Graduate Diploma of Crisis Leadership qualifications should be considered as a building block for a vocational ECDM professional development practitioner pathway. U.S. Independent Studies courses can be easily integrated into the AQF Units of Competency. The AQF system allows all regions globally to contextualize training delivery while retaining graduates’ knowledge, skills, competency, and capability.

- Recommendation 3: Emergency Management entry-level roles should be linked to full-time/internship positions that integrate vocational education programs, offering a balance of work experience, and academic understanding whilst also providing a managed mentored learning environment for developing practitioners.

- Recommendation 4: The Feldmann-Jensen study (Feldmann-Jensen, Shirley, Steven Jensen, and Sandy Smith, 2017) could be revisited and used to determine a single core qualification structure (i.e., 50% of each qualification scaffolded and framed towards a National Qualification Standard) for Bachelor’s and Master’s degree programs, the balance contributing to general or local knowledge, skill, and capability using individual electives.

Credentialing

ECDM associations provide their membership with credentialing recognition as a mechanism of encouraging membership. Only one credentialing recognition program that is open to all practitioners has been identified that does not require membership to attain the credential. The remaining credential programs required paid membership before commencing their credential process. The research identifies that each of the programs has specific criteria and regulations, but none offer credential accreditation which adequately reviews an applicant’s knowledge, skills, expertise, and capability. Applicants are not required to demonstrate their understanding and application of comprehensive emergency management across all four main P/E/Cs of PPRR.

Credentialing will be a critical professional development component for emergency, crisis, and disaster practitioners working towards professionalization. The process will involve ensuring terminology doesn’t conflict with the complexities of multiple industry sectors that span the global environment using the same nomenclature. Currently, the industry sector and practitioners will determine which credential program they choose. The challenge will be for the sector to determine and establish a single set of standards in identifying credential alignment to the respective four main P/E/Cs of PPRR.

Practitioners in the ECDM domains are inconsistent in judging the readiness and capabilities of individuals in the field. Various sectors within ECDM value individuals who have the experience to determine their suitability, while educational qualifications are used for another group, and credentials (such as certifications) are allocated to still another group. The alignment of experience, education, and certification is sometimes indistinct and inconsistently implemented throughout the industry.

A competent Emergency, Crisis and Disaster Manager (ECDM) must possess expertise in all three domains – emergency management, crisis management, and disaster management – to perform their duties efficiently:

- Emergency Management: encompasses the coordination and administration of resources and duties related to addressing many aspects of emergencies, with a special focus on readiness, response, and recovery. Unforeseen emergencies may occur suddenly, necessitating prompt action. An ECDM expert must be prepared to manage these circumstances quickly and effectively.

- Crisis Management: refers to the systematic approach used by an organization to address and mitigate the impact of unforeseen and disruptive events that pose a threat to the company or its stakeholders. An ECDM expert must possess the ability to predict and successfully manage crises to prevent their escalation.

- Disaster management: encompasses the administration of both the hazards and the aftermath of disasters. Catastrophes frequently yield extensive consequences and necessitate a synchronized reaction across multiple tiers. An ECDM expert should possess the ability to devise and organize disaster response or crisis management initiatives to minimize the consequences of disasters.

Essentially, each of these characteristics necessitates a distinct combination of expertise and understanding, and they are all interrelated. An ECDM specialist with a comprehensive skill set in handling emergencies, managing crises, and mitigating disasters is extremely valuable in safeguarding the safety and welfare of communities and organizations. This is particularly necessary in our present environment where catastrophes, crises, and disasters are regrettably growing more often and more severe.

- Recommendation 5: An educational doctoral action research project be established and funded to review the disparity and disconnect within the ECDM domains. Addressing the intersection of experience, education, and credentialing within the ECDM domains which are complex due to the diverse nature of the disconnect within the domains.

- Credentialing and Regulation: Credentialing and regulation are crucial for ensuring a skilled and adaptable workforce. This involves the systematic documentation of evidence related to education, training, and professional experience. By implementing comprehensive credentialing systems, professionals may be certain that they meet specific standards of competence.

- Recognizing the Value of Different Credentials: Acknowledging the importance of diverse credentials should be acknowledged. It is crucial to acknowledge that various industries may place different levels of importance on specific sorts of credentials. For instance, certain industries may assign greater importance to hands-on experience, while others may stress formal schooling or specialized qualifications (HBR, 2019).

- Promote Transparency and Clarity: In preventing the confusion between experience, education, and credentialing, it is crucial to enhance transparency and precision. This may entail effectively conveying the requirements and expectations linked to various positions and ensuring that the methods for verifying qualifications are open and easily comprehensible.

Working towards Professionalism

Due to a projected timeline extending to at least 2040 (Cwiak, 2022.), many leading practitioners will retire before the ECDM industry is recognized as a profession. A comparative review examined Australian Paramedics’ Professional recognition journey. The Australian Government established the Paramedicine Board in December 2018, registering paramedicine as a profession after a twenty-four-year-long journey that began in 1994. Australia has seven states, and eleven ambulance services, with 21,177 currently registered paramedics, (Productivity Commission, 2022). This example demonstrates the potential timelines and challenges that ECDM practitioners may face as they work towards gaining global professional recognition.

The timeline could well extend past the proposed 2040 implementation target in Cwiak’s paper (Cwiak, 2022). The comparative review highlighted the difficulty ECDM sectors will face in gaining professional recognition in any country let alone with global recognition and in particular, overcoming administrative obstacles and regional nuances. The final piece of this conundrum raises the issue of how the ECDM sector establishes and finances an unbiased organization that will take on the responsibility for overseeing the registration process of professionals seeking recognition as ECDM Managers.

- Recommendation 6:

- Educational doctoral research be undertaken to identify potential standards across the ECDM domains that guide practitioner professional development pathways towards professionalization.

- U.S. State-based certification alignment, potentially implementing a common framework and guidelines.

- U.S. State-based certifications align with international credential programs to avoid duplication of effort for practitioners and peer-review assessors.

- Alignment of international credentials to be complimentary to each other and not overlapping through the adoption of a common assessment and review criteria.