18 Description of the Typical Emergency Manager: An Assessment of Who Leads in Times of Disaster

Romeo B. Lavarias, DPA

Author

Romeo B. Lavarias, DPA, MA, CEM, Emergency Manager, City of Miramar, FL

Keywords

emergency manager; first responder; certified emergency manager

Abstract

The emergency manager that is identified or hired to address the operation of an organization during times of natural or man-made disasters has a critical role in how successful the organization will be when disaster strikes. The role will require dedication, experience, knowledge, skills, and the ability to operate successfully in a chaotic environment when things are at their worst. The role will require that the person tasked with leading their respective jurisdiction/organization before, during and after a disaster will possess insufficient time, information, and resources. Yet, these individuals will have to exhibit leadership, critical thinking and decision-making that will determine repercussions and consequences on their organization and the jurisdiction that they are responsible to serve. While a great deal of information has been learned from past disasters, new technologies, and advances in disaster research, there are still significant challenges that an emergency manager will have to deal with including unpredictable events, weather systems that are larger and fiercer, year-long pandemics, and active shooter incidents. Coupled with these are a reduced workforce, institutional knowledge that is now missing due to retirements, complex but useful disaster technologies (Geographic Information Systems, Artificial Intelligence, Drones, etc.), and a social media presence that will highlight the efficacy of every decision made by the emergency manager. In light of this situation, the following chapter examines research from academic studies, academic journal articles, and other sources that delve into the operational environment an emergency manager must navigate in along with the knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSA) an emergency manager must possess to operate effectively during times of disaster. The findings in the chapter will reveal the skillset that an emergency manager must possess to lessen the devastating impact of disasters.

Introduction and Problem Statement

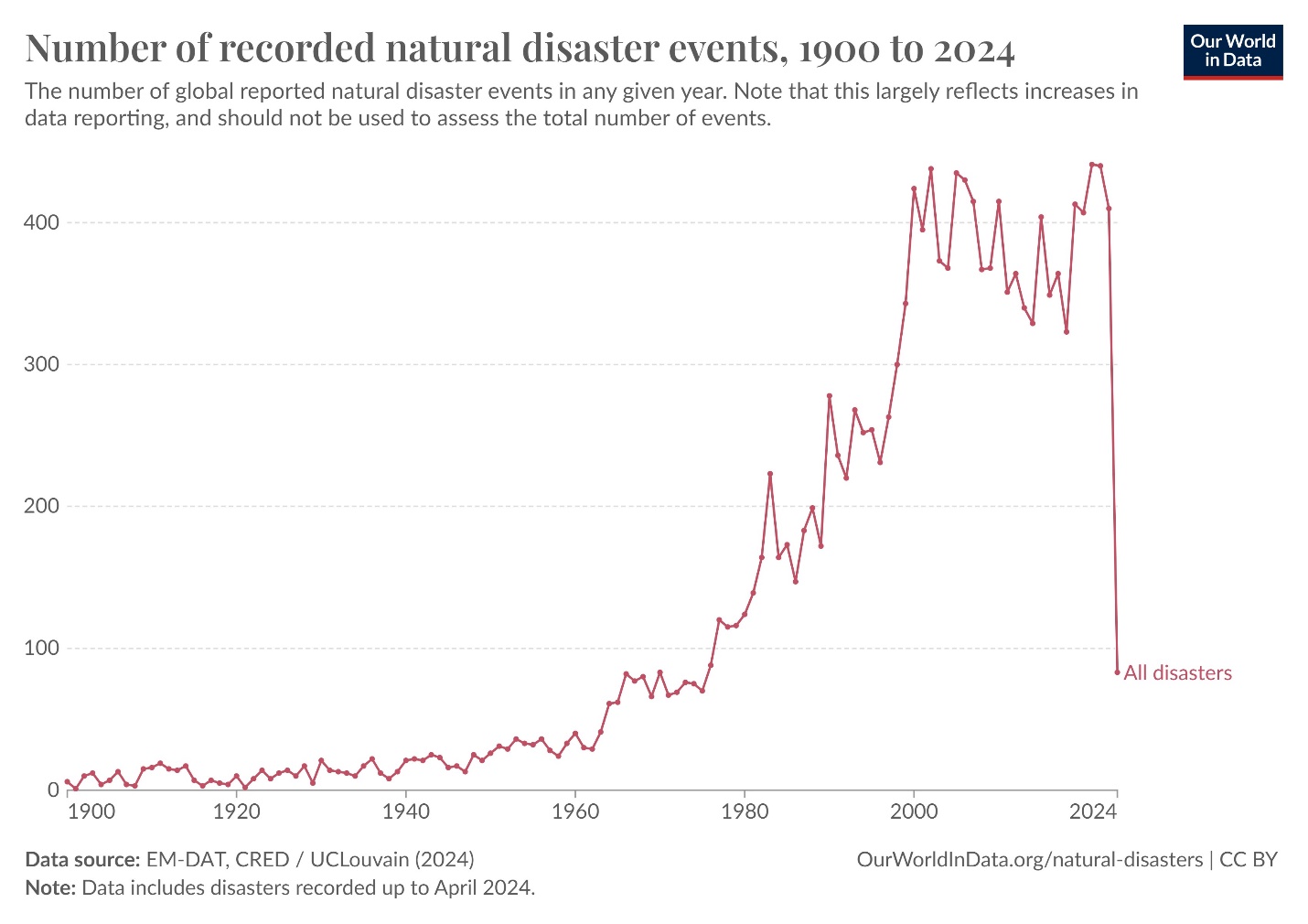

Internationally, disasters (both natural and man-made) have become more frequent and devastating (Ritchie and Rosado, 2024) as depicted in the graph below. The result has led to millions of individuals being negatively impacted (i.e., death, injuries, loss of loved ones, loss of property, economic damages, and lowered quality of life). The segments of society that suffer the most tend to be the elderly, lower socio-economic groups, and disabled. According to the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), “estimates show natural hazard disasters in 2023 costing $250 billion in U.S. dollars, with a human toll of 74,000 lives. However, the figures are heavily skewed towards richer nations and big-well reported events (UNDRR, 2024).

On average, there are about 6,800 natural disasters that happen every year worldwide that affect 218 million people and claim 68,000 lives (Joshi, 2024). According to Kunz & Pattison (2024), “localized natural disasters [in the United States], averaging 18 occurrences per year since 2018, quickly become state and national emergencies, with recovery costs easily exceeding $1 billion each.” In fact, in a typical year there are 10,000 thunderstorms, 5,000 floods, and 1,000 tornadoes across the United States (Sheffi, 2015, pg. 191). These natural disasters coupled with year-round pandemics and active shooters present a host of new emergency management issues that had not been seen or experienced before.

Prior to this, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 (Sendai Framework) was adopted by the United Nations World Conference in Sendai, Japan, on March 18, 2015, to articulate the many facets of disaster risk reduction, one of which is “recognition of stakeholders and their roles.” It is this facet that this research will examine in terms of the stakeholders (e.g., the emergency managers who would carry out the actions necessary for disaster risk reduction). To alleviate the negative impacts of disasters, this responsibility shall fall upon those individuals designated as “emergency managers.” These individuals are found internationally and nationally in every level of government, the private sector, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), faith-based organizations, and volunteer organizations.

How the response and recovery efforts after each of these natural/man-made disasters is carried out depends on the responsible emergency management organization in charge. Discovering the cause of a catastrophe is mostly an exercise in hindsight (McKinney, pg. 43). However, there are many questions asked about the emergency manager posed to assign blame. Who is the emergency manager in charge of the organization and did he/she make the right critical decisions? Does he/she have the requisite education, experience, knowledge, skills, and abilities to lead in an effective manner?

At no time in the history of the profession of emergency management has the need for trained and knowledgeable emergency management personnel been so important. Emergency management personnel must contend with the increasing frequency and ferocity of natural disasters (e.g., hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, extreme heat, tsunamis, landslides, volcanic eruptions, wildfires, blizzards, etc.), yearlong pandemics (e.g., COVID-19, measles, SARS, etc.), and man-made disasters (e.g., active shooter, cyber hacking, domestic terrorism, riots, demonstrations, etc.). In addition, there are vivid reminders of the failures of prior emergency management responses (e.g., Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Hurricane Maria in 2017, and the Maui Wildfire in 2023). Each of these underscore the need to develop the knowledge, skills, and abilities that an emergency manager should possess (A. Morris, personal communication, January 22, 2024).

While there has been a proliferation of higher education degree programs that provide associate’s, bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral programs in emergency management, the students who graduate into the field of emergency management may not have any disaster experience. Adding to this situation is the retirement of seasoned emergency management personnel (Mekouar, 2024) who would pass on their knowledge thus limiting the effectiveness of the new generation of personnel. There is also the ever-current environment of lack of resources (e.g., personnel, competitive salaries, access to training, equipment, etc.) where emergency management personnel are tasked with being the “lead” in all phases of emergency management before, during, and after a disaster, but have no full authority or support, and are yet subsequently to “blame” for not responding quick enough and recovering sooner from a disaster’s impact.

In spite of the difficult described environment, many organizations (i.e., public, private, and non-governmental) have created positions to address the need to coordinate emergency management. The result has been an explosion of job titles. In a recent LinkedIn entry (Moquin, 2024), it was asked if the emergency management industry has an identity problem based on the variety of job titles that currently exist. The responses were extensive and the varied job titles are listed in Text Box 1.

Emergency Management Job Titles

- Emergency Manager

- Crisis Manager

- Director of Emergency Management

- Emergency Management Program Manager

- Emergency Management Coordinator

- Emergency Management Specialist

- Emergency Preparedness Manager

- Director of Emergency Preparedness

- Emergency Preparedness Coordinator

- Director of Safety and Security

- Safety and Security Manager

- Director of Crisis Management

- Crisis Manager

- Crisis Management Analyst

- Resilience Manager

- Chief Resilience Officer

- Director of Resilience

- Director of Operational Resilience

- Operational Resilience Analyst

- Director of Business Continuity

- Business Continuity Manager

- Business Continuity Coordinator

- Business Continuity Specialist

- Disaster Recovery Specialist

- Incident Management Coordinator

- Manager of School Safety

- Emergency Services Coordinator

- Emergency Services Manager

- Emergency Services Specialist

- Emergency Services Director

- Operational Resilience Manager

- Emergency Planning & Readiness Program Manager

- Emergency preparedness and Response Advisor

- Response Readiness Advisor

- Principal for Emergency Preparedness and Response

- Disaster Manager

- Disaster Programme Manager

- Crisis Programme Manager

- Disaster Programme Manager

- Sr. Disaster Program Manager

- Regional Disaster Officer

- Readiness Officer

- Disaster Preparedness Officer

- Emergency Management Officer

- Contingency Planning Specialist/Officer

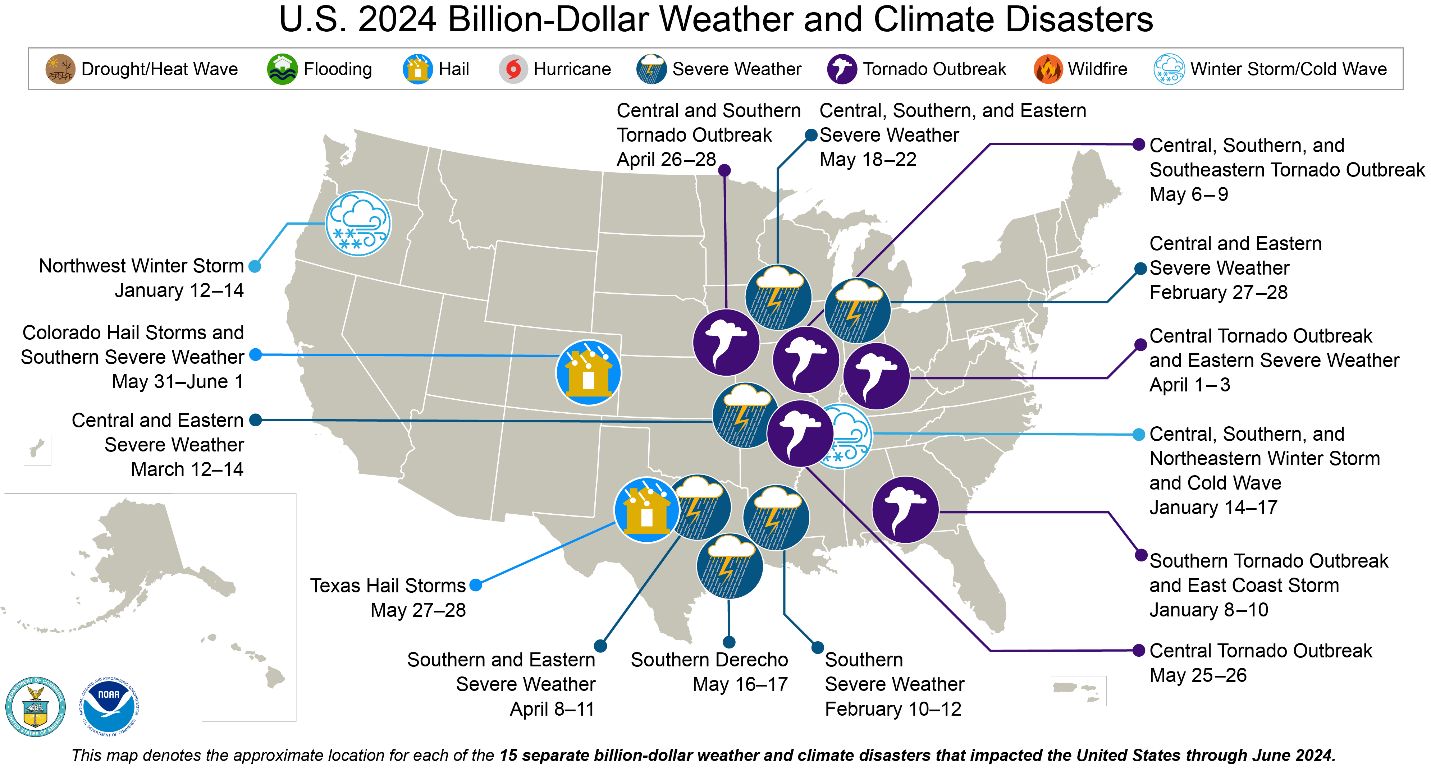

Regardless of the multitude of job titles, it has become apparent that there is an increasing amount of reliance on the individuals who have these positions to be able to lead organizations through natural and man-made disasters. There is also a need for these individuals to reduce risk, especially since the costs of natural disasters in the United States in 2023 alone was $28 billion and as of July 9, 2024 there are have been 15 confirmed weather/climate disaster events with losses exceeding $1 billion in the United States.

These individuals hired in these positions must facilitate both vertical and horizontal coordination between numerous NGOs, government departments, and private companies, and demonstrate a plethora of skills including the ability to adapt and make hard and fast decisions. The skills, tasks, and roles expected of emergency managers are superimposed onto bureaucratic systems that remain relatively rigid in their planning, protocols, and processes (Oostlander, et. al., p.6).

This challenging context leads to the question pertinent to the study in this chapter: who makes up the diverse population of emergency management professionals that dictate the costly success or failure of how organizations deal with disaster?

Literature Review

The literature on this topic could be categorized in two ways:

-

- The current multi-organizational environment that emergency managers must operate in; and

- The knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs) that an emergency manager must possess to be successful in an operational or leadership role.

Operational Environment

To understand the organizational environment that an emergency manager must operate in and promote success, it might be wise to refer to a comment made by Dwight Waldo (1980) in his book, The Enterprise of Public Administration: A Summary View. He stated:

When [serving as] editor-in-chief of the Public Administration Review, I tried to identify someone willing to organize a symposium on what I called alternately disaster management and emergency management. . . . . Advertising for a symposium editor failed: not a single candidate. The reasons for our collective indifference [were] several, including a perceived lack of professional pay off in this area and vague sense that it is peculiar if not un-American to be looking for trouble. Most fundamentally I think this is involved: Administration is concerned with rationality, order, calculability, efficiency. How can these be applied to the unpredictable, the disorderly, the destructive? (p.185)

What Waldo was suggesting is that It is very challenging for organizations to operate in normal times when basic resources are plentiful. However, it is even more problematic to address community needs when lifelines (such as safety and security; health and medical; communications; hazardous materials; food, water, shelter; energy including power & fuel; and transportation), are cut off, along with not having the right personnel to address these concerns.

Complicating the physical environment aside from these basic community lifelines are the numerous levels of government actors (whether state, local, tribal, and territorial), NGOs (non-profit organizations), interest groups, professional organizations, voluntary associations, and individual politicians that emergency managers may have to work alongside. Each of these has their own agendas, as well as operating under their respective jurisdiction’s laws, organizational/bureaucratic norms, respective professions, and a demanding public interest.

This lends to the “punctuated equilibrium” concept posed by Frank Baumgartner and Bryan Jones where the theory states that:

policymaking is an inherently unstable process with critics who will oppose change, no matter what problem or solution is codified in law. In time, these critics, abetted by external events, can erode confidence in the solution, allowing those in opposition to undermine or overturn it and replace it with an option they prefer. How long the solution has remained in effect as public policy is irrelevant; external forces eventually open the problem definition stream and debate begins anew over the nature of the problem; while, indeed, the problem itself may have morphed in the interim. Once this occurs, the existing equilibrium within the policy arena becomes unsettled, or punctuated, and what was once a reasonably stable policy environment now becomes fraught with instability (p. 242).

The specific question of who the typical emergency manager has been examined by McEntire, et.al (2001) through their citation of Goldschalk’s (1991) “discussion of comprehensive emergency management (…) and the contributions that actors from various sectors make towards disaster reduction” (p.145). Their findings stemmed from their examination of “invulnerable development” or “comprehensive emergency management” where a variety of occupations have a role in it (e.g., Geographers, Meteorologists, Engineers, Anthropologists, Economists, Sociologists, Psychologists, Political Scientists, and Epidemiologists).

The latest query into who makes up the emergency management field was examined by Wanless et al. (2023) when the National Weather Service (NWS) forecasters desired better understanding of the emergency management personnel that “receive, process and forecast information” (pg. 2). The NWS utilizes a wide variety of data and tools that facilitate the delivery of accurate and timely information. However, the NWS had very little data and almost no tools that facilitated knowledge about diverse populations of emergency managers that receive, process, and use the information the NWS provides. To study who makes up the diverse community of emergency managers, an analysis of the different types of organizations that are involved in emergency management will be undertaken. The types of organizations that will be analyzed are: public sector, private sector, and the non-profit sector.

Organizational Analysis

The public sector is that segment of society typically made-up government departments, agencies, and offices (McEntire, 2022) whose main responsibility is to maintain the public order and provide public services. McKinney (2018, pg. 98) states that “nine out of ten Americans say that government should play a major role in responding to disasters.” But trying to figure out which level of government has the responsibility before, during, and after a disaster can lead to confusion and misunderstanding which can complicate the response and recovery efforts. What is eye opening is that neither the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) or State Emergency Offices have a primary responsibility for disasters (McKinney, pg. 99). Based on Home Rule, states have transferred the responsibility to the government that is closest to the people – to the counties, cities, and towns. Regardless, every level of government (i.e., local, state, tribal, and federal) has a multitude of actors that will become involved in disasters. For instance:

- Local governments are municipal organizations within county/parish jurisdictions. Many local governments at the city level may have emergency management coordinators or emergency managers that run their emergency management activities. Some of these individuals are part-time while others work full-time. These individuals may be located in a semi-autonomous office or under the fire department (or another government unit). At the county/parish level, there may be a county emergency management director that directs all emergency management activities within the county. His/her staff may be made up of emergency management coordinators, mitigation planners, WebEOC planners, etc. Normally, a county will have more resources and/or expertise than cities. However, as the emergency management field has grown in availability of knowledge and training, and counties have been shown to be unable to directly assist since they must help other cities within their boundaries, cities have learned to ‘stand’ on their own without county assistance and have been more adept at increasing their own expertise and/or resources. Overall though it is at the city/county level where all disasters are considered “local” and the responsibility of that jurisdiction unless the situation requires additional resources beyond their respective capability thus requiring state government assistance.

- State governments are those agencies that are involved in response and recovery operations (McEntire, 2022). Acting as the intermediary between the federal government (usually FEMA or the Federal Emergency Management Agency), state governments’ emergency management divisions will coordinate any response and recovery warranted by the extent of the damage.

- Tribal Government encompasses the 574 federally recognized tribes (as of January 28, 2022, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2024). Each tribe is unique in terms of their history, customs, language, laws, and view of emergency management. Regardless, a tribal government is considered their own sovereign nation and may deal directly with, and receive funding from the federal government. However, tribal governments may still interact to a large degree with individual states.

- The federal government is the national unit that has the highest emergency management authority in the United States (McEntire, 2022). Under the auspices of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), FEMA will spearhead disaster response and recovery efforts on a nationwide scale. FEMA operates out of 10 regional offices to coordinate federal response and recovery efforts between their respective regions and FEMA. However, FEMA also coordinates with countless federal agencies to help mitigation, prepare for and react to disasters.

These levels of government are made up of numerous and various actors. Each of which possess overlapping political authorities, coupled with varying degrees of education, experience, knowledge, skills, and abilities. It subsequently creates an environment of “failure to achieve an effective, rational response to a disaster will usually lead to a political “blame game” where different groups blame each other for what has happened and why” (Roberts, P.S. et al., 2020, Chapter 9, p. 244). Invariably, when this happens, research studies, formal congressional hearings, fact-finding commissions, along with other investigatory efforts seek to obtain testimony, gather information, and make recommendations (Roberts, P.S. et al., 2020, Chapter 9, p. 246). The effort takes time. And as public attention wanes to other headlining topics, so does the political will to make substantive changes to the emergency management process environment, policies, structures, and infrastructure through mitigation efforts. What is left are individual experts, interest groups, and participating organizations each offering their recommendations that may contradict each other. It leaves emergency management reform with a history of problems that are often only partially identified and never fully resolved (Roberts, P.S. et al., 2020, Chapter 9, p. 247). Yet somehow, the emergency manager must try to make sense of the recommendations and make them operational within the organization through training and exercise. Complicating the emergency manager’s environment further is the fact that:

Disasters depend upon the ongoing social order, its everyday relations to the habitat and the larger historical circumstances that shape or frustrate these matters. Because of this, as technology, society and the natural environment change and evolve, so do disasters. In addition to the traditional disaster landscape, new layers are being added that reflect novel threats that once did not exist; new pathways are being created that allow their destructive nature to affect more people ever further away; and greater levels of complexity frustrate our attempts at control (Etkin, pg. 331).

This was seen in Cyclone Gabrielle that struck New Zealand in mid-February 2023, which warranted the third time in New Zealand’s history where a national state of emergency was declared. The storm left hundreds of thousands without power, led to cancelation of flights, and damaged roads, homes, and infrastructure (NASA Earth Observatory, 2023). However, what made it notable was the determination from an independent review of Hawke’s Bay’s Civil Defence, where it stated that the national emergency management system “sets up good people to fail.” The review outlined how “simply overwhelmed the officials involved in the response” were. The officials did not have “situational awareness” meaning they did not plan for the worst-case scenario. Other criticisms included: 1.) plans not having any operational detail, 2.) emergency management staff being over-confidant about their readiness based on their experience in handling the Covid-19 outbreak, 3.) emergency management staff suffering from inexperience and “optimism bias” where they tended to take the best-case scenario approach rather than precautionary approach to planning, communication, and warnings, 4.) bureaucratic decision-making from the Group Emergency Coordination Center that hampered delivery of welfare services, and 5.) the limited number of trained emergency management staff and confidant controllers which led to inefficiencies, confusion, and burnout. In light of these challenges, the final decision has been to throw out the old model and complete an overhaul of New Zealand’s approach to emergency management. Other nations also struggle with similar challenges.

The Private Sector

FEMA has purported that the key to emergency management is like a “three-legged stool” where one leg is government, one leg is the private sector, and one leg is nonprofit organizations. The private sector is challenged on two fronts. First, disasters may impact their business process and/or base of operations such as interrupting their supply chains, preventing their employees from coming to work due to road closures, compromising/destroying their buildings or their sales inventory, and/or losing vital records. Second, the private sector must not only deal with a disaster in their area but must also react to any disasters outside of their area that might disrupt their supply chain. The interruption to their supply chain will negatively impact the manufacturing of their product which may impact its standing with their customers, which will subsequently lower their profit margin, negate their brand name, and lessen its stock price.

Due to this reality, the private sector uses business continuity to focus on issues such as the affected work-in-process inventory, alternate fabs (fabrication sites), logistics, products, and customers (Sheffi, 2015, pg. 102). To maintain their competitive edge, businesses accumulate skills and develop better methods for response. After a crisis, much like government, businesses will conduct a “hotwash” performed immediately after the event, and a more careful analysis later (Sheffi, 2015, pg. 103). The individuals that carry out such efforts are often referred to as either business continuity planners, risk managers, crisis managers, etc. Through the efforts of these educated and trained individuals, businesses seek to build redundancy and increasing flexibility of supply chain assets and processes (Sheffi, 2015, pg. 129). Unlike the public sector, the private sector seeks to prosper, and that means they must grow, and manage the risks and uncertainties inherent in today’s environment. To accomplish this, the private sector may participate in emergency management through the following sectors (McEntire, 2022):

- business continuity, disaster recovery and risk management,

- transportation,

- sheltering and housing,

- emergency and long-term medical care,

- media reporting,

- volunteers and donations,

- insurance provision and claim settlement,

- utility restoration and community reconstruction,

- vending of goods and services.

In summary, the private sector’s primary focus on profitability, increased market share, and competitiveness relies significantly on its ability to address and mitigate against disruptions (i.e., disasters that may threaten the private sector’s focus). The private sector’s “emergency management” personnel must be cognizant of potential disruptions internationally due to the products/services they require to function, or if their own products/services are bought internationally.

The Nonprofit Sector

The final leg of the stool of emergency management is the nonprofit sector. Traditional organizations such as the Red Cross and Red Crescent Society, Salvation Army, etc. have been at the early forefront of aiding in the aftermath of a disaster. However, changes in volunteerism and a rise on the number of other disaster charitable organizations has made it difficult for them to be competitive. Older and retired Americans had been the predominant demographic who volunteer overall. However, issues such as Covid and new senior attitudes about being more active in retirement have reduced volunteer numbers. In Florida, the rate of volunteerism in 2017 was 23% of residents. In 2023, the number dropped to 16%. This reduction has caused volunteer staff to wear many more hats than previously.

Increasing competition for volunteers has come from the faith-based organizations (e.g., Southern Baptist, Mennonite Disaster Services, etc.), Community Groups (e.g., Rotary Club, Boy Scouts, etc.) and other independent volunteer organizations (e.g., Team Rubicon). Regardless, the personnel that run the emergency management component of these organizations will undoubtedly be involved in almost all aspects of the emergency management response and recovery efforts.

In summary, the “emergency management” personnel in the nonprofit sector often operate as a quasi-governmental entity with a chain of command. The structure allows them to operate and collaborate on an international and national scale quickly and with better effectiveness and efficiency.

Through this examination of the different fields that emergency managers may find themselves working in it becomes clear that that they must possess basic KSAs in emergency management and be able to apply it through potentially different “lenses” of their respective employer as well as the function that their employer utilizes emergency management. The research into what an emergency manager should be will need to begin with what currently makes up the population of emergency managers currently in the field.

Knowledge, Skills, and Abilities of Emergency Managers

The above-described emergency management organizations all have their unique niche when it comes to disaster responsibilities. However, as the discussion moves towards who the typical emergency manager is or should be, it is necessary to examine what education, experience, knowledge, skills, and abilities an emergency manager should possess. In the past there have been numerous examples of emergency managers who were appointed based on their political affiliation with senior leadership, but lacked the requisite education, experience, KSAs in emergency management. Some examples include:

- Michael D. Brown, FEMA Director from 2003-2005, who was appointed by President George W. Bush in January 2003. Brown’s handling of Hurricane Katrina (2005) led to his ouster amid accusations that he lacked disaster management experience. Lack of emergency management experience, particularly at the state level, also made him a less-effective FEMA leader amongst the organization’s staff.

- Governor Rick Scott of Florida appointed 29-year-old Wes Maul as the Director Florida Division of Emergency Management in 2018. Maul had one year of experience in emergency management, and prior to his appointment he was tasked with coordinating Governor Scott’s travel and daily schedule while he worked for the governor (Breslin, 2017). During his two-year appointment he had been criticized for his holding up of disaster recovery funds (Sarkissian, 2019).

- Maui County Emergency Management Agency Administrator Herman Andaya resigned almost immediately after the Maui wildfire (August 2023) amid criticism on how he handled the incident. At a press conference, when asked if he was qualified, he replied that he had worked on numerous emergencies and took FEMA classes (Kim, 2023).

These examples, with Maui being the most recent, have driven several initiatives to lay out the actual education, experience, knowledge, skills, and abilities that an emergency manager should possess. For instance, the State of Florida currently has two bills (SB-1262 and HB-1567) that are making its way through the legislature. Both bills require County Emergency Management Agency Directors to meet minimum training and education requirements established by the Florida Division of Emergency Management (FEPA, 2024). The bills propose that the director must meet the following minimum training and education qualifications (Qualifications for County Emergency Management Directors, 2024, p.2-3):

- Fifty hours of training in business or public administration, business or public management, or emergency management or preparedness. A bachelor’s degree may be substituted for this requirement.

- Four years of verifiable experience in comprehensive emergency management services, which includes improving preparedness for emergency and disaster protection, prevention, mitigation, response, and recovery, with direct supervisory responsibility for responding to at least one emergency or disaster.

- A master’s degree in emergency preparedness or management, business, or public administration, communications, finance, homeland security, public health, criminal justices, meteorology, or environmental science may be substituted for 2 years of experience required under this sub-paragraph but not for the required supervisory experience.

- A valid accreditation as a Certified Master Exercise Practitioner through the Federal Emergency Management Agency, as a Certified Emergency Manager through the International Association of Emergency Managers, or as a Florida Professional Emergency Manager through the Florida Professional Emergency Manager Association may be substituted for the requirements of this sub-paragraph. A certification used as substitution for the requirements of this sub-paragraph must be currently maintained in good standing at all times until the actual time and experience requirements satisfying this sub-paragraph are met by the appointee.

- One hundred fifty hours in comprehensive emergency management training provided through or approved by the Federal Emergency Management Agency or its successor, including completion of the following National Incident Management System courses, or equivalent courses established by the Federal Emergency Management Agency through the Emergency Management Institute. This includes training courses that must have been completed no earlier than 10 years preceding the date of appointment, regardless of whether it is an initial appointment or reappointment:

-

- ICS-100: Introduction to the Incident Command System

- ICS-200: Basic Incident Command System for Initial Response

- ICS-300: Intermediate ICS for Expanding Incidents

- ICS-400: Advanced ICS for Command and General Staff

- ICS-700: National Incident Management System, An Introduction

- ICS-800: National Response Framework (NRF), An Introduction

Aside from the State of Florida Legislature working towards identifying and mandating the education, experience, and KSAs of emergency managers, the International Association of Emergency Managers (IAEM), a professional emergency management organization, is working towards establishing professional criteria on a wider scale. IAEM’s Advocacy and Awareness Caucus has developed four objectives where Objective 2 is to “improve the communication and recruitment of EM job positions by creating a plan for the creation of an EM job description splash page” (Advocacy & Awareness, 2023). The key result for Objective 2 is “develop a detailed roadmap for creating the EM job description splash page, broken down into specific sectors and by the size of jurisdiction” (Advocacy & Awareness, 2023). It has led towards the development of the Emergency Management Program Guidance document where Objective 1 is to “assist decision makers in aligning new EM positions and programs to the needs of their communities and organizations” (Advocacy & Awareness, 2024, pg. 1). The group also endorses the emergency management principles document developed by scholars and practitioners affiliated with the FEMA Higher Education Program which defines the profession and discusses vision, mission, and program principles (e.g., Comprehensive, Progressive, Risk-Driven, Integrated, Collaborative, Coordinated, Flexible, and Professional). This may help guide the development of emergency management programs in organizations, and subsequently:

- the nature of leadership and executive direction;

- the foundational program, characteristics, and elements;

- recommended functional activities; and

- the emergency management skill sets necessary for an emergency manager to possess to run the emergency management program.

The major point this research is attempting to establish that a clear understanding is needed to understand the basic KSAs that the position that the emergency manager must possess to be effective in times of disaster. It is through their knowledgeable decision making that the impact of disasters may be minimized in terms of dollars and lives. Much has been developed on what the KSAs should be. However, there is a lack of understanding of who these managers are, what they know, and what they don’t know.

Methodology

Much has been researched and written about recent disasters due to their impact on peoples’ lives worldwide. However, due to the uniqueness of the field of emergency management in terms of its “age” compared to other social sciences, there has been very little research conducted on the types of people who carry the title of “emergency managers” in the national and international settings. In fact, much of emergency management literature covers what emergency managers should know in their capacity as an emergency manager (i.e., leadership, critical thinking, decision-making, etc.) without discussion of who they are. So much of the research for this chapter has consisted of literature review where the sources were derived from books, academic journal articles, and news articles.

In addition, efforts (via email and phone calls) were made to access information from The International Association of Emergency Management Society (TIEMS), and the International Association of Emergency Managers (IAEM). Both organizations were created to advance the emergency management profession on an international platform. TIEMS was founded in Washington, USA in 1993 with its headquarters in Brussels, Belgium. TIEMS has chapters in the following countries: Belgium, Luxemburg, the Netherlands, China, Finland, France, India, Iraq, Italy, Korea, Middle East, North Africa, Nigeria, West Africa, the Philippines, Romania, South Africa, the United States, and Ukraine. The purpose of TIEMS is to, “prepare the world for emergencies” by providing a global forum for education, training, certification, and policy for emergency and disaster management” (TIEMS, 2024). This organization states that their members “constitute a large international multidisciplinary group of experts with different educational background and various experience in the field of emergency management and disaster response” (TIEMS, 2024). It appears that though TIEMS is prevalent throughout the world, they recognize the varying backgrounds of their members as well. However, TIEMS provided no response. The researcher will be making efforts to join TIEMS and seek to access their membership lists as a fellow member.

IAEM is very similar to TIEMS as well. Currently having around 6,000 members worldwide, their purpose is to serve as a non-profit educational organization dedicated to promoting the “Principles of Emergency Management” and representing those professionals whose goals are saving lives and protecting property and the environment during emergencies and disasters.” (IAEM, 2024). They were founded in 1952 as the U.S. Civil Defense Council, becoming the National Coordinating Council of Emergency Management in 1985, and the International Association of Emergency Managers in 1997 with their headquarters in Falls Church, Virginia. The organization has three (3) worldwide councils: IAEM-Oceania (Australia, New Zealand, and all Pacific islands and nations), IAEM-Canada (all Provinces and Territories) and IAEM- USA (all 50 states, Puerto Rico, U.S. Virgin Islands, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. territories of American Samoa, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands). In addition, IAEM also has eight (8) Ad Hoc Geographical Regions that encompass Africa, Asia, Europa, Japan, Latin America, Middle East, and Israel (IAEM, 2024). It had been proposed to examine their respective membership rosters and analyze their members backgrounds. However, access to the membership rosters was not made readily available to the researcher.

Regardless, the first serious study of the emergency management professional remains the research conducted by the Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis (IPPRA) at the University of Oklahoma (Wanless, et al., 2023). To address this issue, IPPRA created a comprehensive database from scratch. Through the website examination of FEMA, State Emergency Management Associations, and jurisdictions, IPPRA compiled an initial database of over 4,000 emergency managers across the United States. All data is made publicly available in Harvard’s Dataverse located in https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/emsurvey. While mainly created to survey on how emergency managers like to receive weather information, the study did collect demographic information in its first wave of research questions. It is proposed to access this information and build upon it with additional demographic questions and send it out internationally.

Findings and Solutions

The Wanless article (2023, p.3) titled “Social Science Datasets, Research Instruments, and Data Ethics: The Extreme Weather and Emergency Management Survey” appears to be the closest academic effort to formally examine and identify who/what is the United States typical emergency manager. The study was created by the National Weather Service (NWS) Prediction Center with the University of Oklahoma’s Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis, Cooperative Institute for Severe and High Impact Weather Research and Operations, NOAA/National Severe Storms Laboratory, the Department of Public Administration, University of Illinois, and the Department of Public Management, John Jay College of Criminal Justice. The efforts of the authors revealed that there is “little data and almost no tools that facilitate . . . the diverse populations of emergency managers that receive, process, and use the information they provide.” In fact, their research had revealed that there is not a current or standardized list of local emergency managers across the country let alone internationally. The study did create a database of emergency managers (https://www.undrr.org/explainer/uncounted-costs-of-disasters-2023) title through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), state emergency management professional organizations, and governmental jurisdictions. However, even though a list of over 4,000 emergency managers was generated, only 720 (18%) had participated in their survey and the respondents were all from the United States. A similar study was presented at the 2024 FEMA’s HigherEd Symposium titled, “Who Are Our Emergency Management Students?” (Bennett-Gayle, 2024). The study surveyed emergency management students and collected data on their demographics (gender, race, and age range) along with their reasons for interest in emergency management, years of professional experience, level of importance of soft skills to emergency management, level of knowledge of student competencies in emergency management, level of importance of subject area skills to emergency management, career goals, etc., This type of research has a “captured” sample size in that it can be completed by emergency management students via their respective emergency management academic programs and institutions. In fact, many instructors may even provide extra credit for completing the survey. Regardless, the research provides findings that may aid in the development and refinement of emergency management degree programs for them to be more effective in providing the KSAs that these future emergency managers will require to address the extensive disasters that have become more prevalent.

Many research studies reviewed had examined what roles and KSAs emergency managers should possess using small sample pools. Some studies even looked at what the future needs are of the emergency manager (Pine, 2003). Oostlander, et al., (2020), recognized that Canadian emergency managers (EM) and emergency social services directors (ESSD) fill a critical role in disaster risk reduction. The purpose of their research was to understand their perceptions of barriers, vulnerabilities, and capabilities within their roles. Their sample pool were 15 EMs and 6 ESSDs from six Canadian provinces. In Chang & Wang’s article (2021) the researchers examined the collaborative competencies local emergency managers should possess in emergencies, and their survey pool was made up of only 16 Taiwanese emergency management practitioners and scholars. All studies approached their examination of the emergency manager as he/she interacts with their respective emergency management environment whether through the emergency manager’s ability to collaborate, secure the appropriate KSAs necessary, adapt to rapidly changing technology, anticipate worst case scenarios, utilize critical thinking skills, etc., However, many of the studies did not have a significant sample pool which may be due to the lack of an inventory or listing of active emergency managers. So, while the bulk of research is on the emergency management environment that an emergency manager must operate within along with the KSAs that will be required of him/her, there is no actual inventory of who and what makes up an emergency manager both nationally and internationally.

Discussion of Implications

When the United Nations released The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 in 2015, it outlined an international, action-oriented approach to achieving a reduction in disaster risks. The Sendai Framework’s targets, priorities for action, and guiding principles spanned across economic, physical, social, cultural, and environmental domains. A major gap of the study was the failure to identify the emergency managers who are to lead this reduction in disaster risks and their KSAs necessary to be successful in carrying out the actions . The scale of Sendai’s desired accomplishment would involve extensive coordination of individuals who operate in international, national, state, tribal, local, NGO, private sector, faith-based organizations. Without a clear understanding of who will carry out these actions, how can the 187 United Nation members that signed the Sendai Framework accomplish its purpose? Unfortunately, omission has occurred while the pace of disasters has increased significantly. As stated earlier, there are approximately 68,000 natural disasters each year, and each with their associated economic, physical, and fatality/injuries. According to the International Special Interest Group sponsored by FEMA, “the U.S. suffered an extreme weather disaster that caused at least $1 billion in economic damage about once every four months. In 2023, there was one every thirteen days on average. (Phipps, 2024).”

Originally, the need for emergency management professionals arose from society’s needs for a full-time, technically trained individual to facilitate response and recovery in times of disaster. Today, emergency managers engage in a range of roles and tasks that span all four phases of the disaster management cycle (i.e., preparedness, response, recovery, and mitigation). The purpose of this chapter was to explore the current make-up of an emergency manager from an international perspective and to establish basic KSA’s they should possess to be effective for their respective communities.

The evolution of emergency management as a profession throughout the world, especially in the last two decades, has been highlighted by the increasing number of individuals seeking higher education degrees in the field of emergency/disaster/crisis management. This is a significant shift from the executive leaders (e.g., mayors, county/city managers, fire chiefs, and police chiefs) who would often, in the past, lead all disasters that should befall their respective jurisdiction. While these individuals may be appropriate for the response phase of a disaster, they are not trained in the other emergency management phases of recovery, mitigation, and preparedness which all have an impact on how well the response phase is handled. It is interesting to note that there is value for both the “academic” (those educated in emergency management through degree programs) and the “practitioner” (the first responder who deals directly with a disaster). Both education and experience are becoming necessary to address the increasingly frequent and extensive natural disasters along with year-long pandemics and active shooter incidents. These disasters will require a “pracademic” who is both educated in a wide variety of emergency management techniques coupled with the experience with dealing with disasters in their respective jurisdiction and/or field of specialty.

In addition, the professionalization of the emergency management has been well documented – internationally and in the United States – through state emergency management professional organizations, or national/international emergency organizations such as the International Association of Emergency Managers (IAEM) and The International Emergency Management Society (TIEMS) where all require a combination of education, training, experience, and “outside of work” professional contributions in the field of emergency management to in order to become certified emergency managers.

So based on the Sendai Framework’s recognition of reducing the risk of disasters along with their devastating impacts, the increasing professionalization of the emergency management field, the increasing number of emergency management graduates, and the significant research on the operational environment that emergency managers must perform within along the KSAs they will need to be successful, how can research with small sample sizes support the respective conclusions and recommendations and are truly reflective of the EM population?

What is needed for the emergency management to advance more effectively, efficiently, and collaboratively is a better database of emergency managers both in the United States and for each country so that future studies may be more robust and reflective of the emergency managers in the field. Currently, there is no incentive to maintain a database with all active emergency managers. Nor is there a repository that would be responsible for maintaining the database to ensure it is current. It is proposed that FEMA make the first attempt at creating such a database since it is responsible for providing financial resources to states, tribal, territorial, and local governments in times of disaster. By linking the provision of financial resources towards every level of government, FEMA will be inclined to provide the information as part of their respective compliance for financial resources. From this anticipated success, the database effort may be spread to the private sector, NGOs, and faith-based organizations. Once completed, the database may serve as a resource for future research for scholars and practitioners. It will also provide a model for other countries to incorporate as well.

To address the lack of an emergency manager inventory for the United States it is proposed to create a database at the state and national levels. It can be accomplished by requiring the information below and make it a condition of the funding that local jurisdictions receive. For instance, in the United States, “FEMA provides Emergency Management Performance Grants (EMPG) to all states, local, tribal and territorial emergency management agencies with the funding required for the implementation of the National Preparedness System and works toward the National preparedness Goal of a secure and resilient nation” (FEMA, 2024). This includes:

- Requiring governmental counties/local jurisdictions to maintain an active roster of their emergency management personnel that must be reported to the State level and national level. In addition, each state should also:

- Coordinating with the private sector emergency management organizations to also maintain an up to date of their business continuity planners (the private sector’s equivalent of an emergency manager).

- Coordinating with NGOs to also maintain an up to date of their emergency management staff.

- Ensuring that each roster would contain demographic information, levels of education, emergency management position titles, etc.

- Making each roster available to all participating local, state, tribal, territorial, federal and international emergency management communities as well as for those institutions for higher learning to conduct research.

From this database, research may be conducted with the latest contact information of those individuals involved in emergency management either statewide or nationally. The research conducted over a larger sample size would yield a clearer picture of who is carrying out those emergency management duties successfully, or who are struggling for the reasons they would provide from the surveys they would complete.

To conduct an emergency manager inventory from an international perspective, the above-described methodology can also be conducted by each country under the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030. Under the Sendai Framework, all 13 of its Guiding Principles (page 13-14) are implementable at the national, state, and local levels which will require a great deal of effort of their emergency managers at all levels as well as those outside of the respective country’s government (private sector, faith-based, NGOs, etc.). With a database of emergency managers for each country greater research comparisons may be made that provide a richer and more robust analysis through meta-analysis.

In addition, a database of this type would allow a greater exchange between emergency managers from different parts of the world without having to attend international conferences (which is not feasible on local government budgets). It would also lead to better practice exchange/awareness that many local emergency managers may not be privy to.

Conclusions

In Dwight Waldo’s (1980) book, The Enterprise of Public Administration: A Summary View, he stated that he once tried to identify someone to organize a symposium on emergency management. No one replied nor replied to his advertising for a symposium editor. He deduced that the collective indifference was partly on the un-American effort to look for trouble. But most fundamentally he believed that it was due to the notion that administrators are concerned about rationality, order, calculability, efficiency while disasters are unpredictable, disorderly, and destructive (p.185). It is in this environment that the emergency manager (both nationally and internationally) must operate effectively.

Due to the increasing number of natural and man-made disasters worldwide, it is relevant and mandatory in our world society to understand and support the field of emergency management. Increasing demands are going to be placed upon emergency managers to use their knowledge, skills, and abilities to guide their jurisdictions through myriad impacts of disasters. This is partly due to public expectation that emergency management professionals will carry out their roles effectively and efficiently to respond to their needs before, during, and after a disaster (Oostlander, et.al, 2020, p. 6). The issue is further exacerbated by the following conditions: 1). retirements of senior staff who possess the institutional knowledge on how their respective jurisdictions handled past disasters, 2). the increasing pace of technology especially artificial intelligence (AI), 3). the prolific use of social media that advertises every action taken in times of disasters, 4). the reduction of experienced staff to help offset these conditions and 5). the danger of falling into confirmation bias (seeing what we expect to see) and desirability bias (seeing what we want to see) (Grant, 2021, p. 25).

Consequently, the emergency management research field can no longer continue to know little about the diverse population of emergency managers. In this turbulent world, emergency managers will need to be able to rethink and unlearn information that was based on outdated information from the past. Future scholarly research with their associated recommendations will have severe impacts, both nationally and internationally, on how well it is received and processed for action by emergency managers. It will be incumbent upon scholars and practitioners to question their past routines and critically examine if they will lead to a better future.

References

Advocacy and Awareness Caucus of the International Association of Emergency Managers, Objectives and Key Results-Spring 2023, May 25, 2023.

Advocacy and Awareness Caucus of the International Association of Emergency Managers, Emergency Management Program Guidance, February 27, 2024.

Bennett-Gayle, D. Who are our emergency management students? (Panel). FEMA HigherEd Symposium, June 3-5, 2024, Emergency Management Institute, Emmitsburg, MD.

Boisvert, P. and Moore, R. (2004). Crisis and emergency management: A guide for managers of the Public Service of Canada, Canadian Centre for Management Development, 2003 Re-print with minor corrections, 2004.

Breslin, S. (2017). Florida’s Emergency Management Director Departs, Replaced by 29-Year-Old With Little Experience, The Weather Channel, September 27, 2017. Retrieved on March 6, 2024, https://weather.com/news/news/florida-emergency-management-director-resigns-bryan-koon

Chang, K. and Wang, W. (2021). Ranking the collaborative competencies of local emergency managers: An analysis of researchers and practitioners’ perceptions in Taiwan, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, Volume 55, March, 2021. Retrieved on June 6, 2024, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S221242092100056X

Crimp, L. (2024, March 25). Cyclone Gabrielle: Speed, scale of disaster ‘overwhelmed’ underprepared officials, report finds. [Radio Broadcast]. Radio New Zealand (RNZ). https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/512621/cyclone-gabrielle-speed-scale-of-disaster-overwhelmed-under-prepared-officials-report-finds

Dervishi, K. and Balderrama, Y. (2023). WLRN Miami/South Florida (2023). U.S. volunteerism rates are down. Florida is reporting the sharpest decline, April 18, 2023. Retrieved https://www.wlrn.org/florida-news/2023-04-18/u-s-volunteerism-rates-are-down-florida-is-reporting-the-sharpest-decline., March 5, 2024,

Dykstra, E. H. (2023). Toward an International System Model in Emergency Management: Information, Communication, and Coordination in Emergency Management – Public and Private Sector Approaches in Different Countries and System. Call for Papers – Public Entity Risk Institute Symposium. https://www.speakersacademy.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/publication_1635.pdf

Etkin, David (2016). Disaster Theory: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Concepts and Causes, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, UK.

Federal Emergency Management Agency (2023, September 20). Community Lifelines. Retrieved April 1, 2024, https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/2020-05/LifelinesFactSheetandPosterv2.pdf

Federal Emergency Management Agency (2024, April 16). Emergency Management Performance Grant. Retrieved June 6, 2024, https://www.fema.gov/grants/preparedness/emergency-management-performance

Florida Emergency Preparedness Association (2024). Bill Tracking-2024 Legislative Session, February 23, 2024.

Grant, A. (2021). Think again: The power of knowing what you don’t know. Penguin Random House, New York, NY.

Ha, K. (2016). Examining professional emergency managers in Korea. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 62, 158-164.

Hannah Ritchie and Pablo Rosado (2022) – “Natural Disasters” Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: ‘https://ourworldindata.org/natural-disasters‘ [Online Resource]

International Association of Emergency Managers (n.d.) [LinkedIn profile]. Retrieved May 5, 2024 from https://www.linkedin.com/search/results/all/?fetchDeterministicClustersOnly=true&heroEntityKey=urn%3Ali%3Aorganization%3A2946802&keywords=international%20association%20of%20emergency%20managers&origin=RICH_QUERY_SUGGESTION&position=0&searchId=a4b8578f-8986-4bf9-beb4-19f091e8c06c&sid=Z2h&spellCorrectionEnabled=false

Jones, G.A. & Ainsworth, C. (2024). Leadership, management, critical thinking, and decisions-making in emergency management: The implications and challenges to a modern approach within an emergency management environment. In McEntire, D. & Phipps, L. (Eds.), Current and Emerging Issues in International Disaster Management (pending).

Joshi, K. (2024). Natural Disaster Statistics 2024 – By Type, Country, Death Toll, Region, World Risk Index and Safety Measures, January 3, 2024. Retrieved on June 6, 2024, https://www.enterpriseappstoday.com/stats/natural-disaster-statistics.html#:~:text=Every%20year%20on%20average%2C%20natural,in%20a%20year%20is%206%2C800.

Kim, Victoria (2023). Maui’s Emergency Management Chief Resigns After Questions About Fire Response, NY Times, August 18, 2023. Retrieved on March 6, 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/18/us/maui-emergency-chief-resigns.html

Kunz, K. and Pattison, S., (2024). How Can States Deal with the Next Crisis?, PA Times, February 2, 2024.

Lavarias, R.B. (2013). A comparative analysis of the moral development of emergency personnel based on the defining issues test. Doctoral dissertation. Nova Southeastern University. Retrieved from NSUWorks, H. Wayne Huizenga School of Business and Entrepreneurship. (58), https://nsuworks.nova.edu/hsbe_etd/58

McEntire, D. A., Fuller, C., Johnston, C.W., Weber, R., (2001). The Future of Emergency Management: The Search for a Paradigm and Policy Guide,

McEntire, David A. (2018). Learning More About the Emergency Management Professional, FEMA Higher Education Program.

McEntire, David A. (2022). Disaster Response and Recovery: Strategies and Tactics for Resilience, Wiley: Hoboken, NJ.

McKinney, Kelly. (2018). Moment of Truth: The Nature of Catastrophes and How to Prepare for Them, Savio Republic, New York.

Mekouar, Dora. February 12, 2024. As Baby Boomers Retire in Droves, Will Immigrants Save the U.S. Economy?, Retrieved from https://www.homelandsecuritynewswire.com/dr20240212-as-baby-boomers-retire-in-droves-will-immigrants-save-u-s-economy

Moquin, Michael. (2024, February 16). #Does our industry have an identity problem? [Thumbnail with link attached] [Post]. LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:7160618884927033344/

NASA Earth Observatory. (2023). Cyclone Gabrielle lashes New Zealand.https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/150972/cyclone-gabrielle-lashes-new-zealand

NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) U.S. Billion Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters (2024). Retrieved https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/billions/, DOI: https://www.doi.org/10.25921/stkw-7w73

Oostlander, S.A., Bournival, V., and O’Sullivan, T.L. (2020). The roles of emergency managers and emergency social service directors to support disaster risk reduction in Canada, International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 51, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101925.

Phipps, L., Chang, R., and Curiel, K. Effectively Managing Disasters, Research, and Collaboration in International Settings (Panel). FEMA HigherEd Symposium, June 3-5, 2024, Emergency Management Institute, Emmitsburg, MD.

Qualifications for County Emergency Management Directors, CS/CS/SB 1262 of Florida Senate. (2024). https://www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2024/1262/?Tab=BillText

Roberts, P.S., Glick, J.A. and Wamsley, G. (2020). The Evolving Federal Role in Emergency Management: Policies and Processes (Eds.), In C.B. Rubin (Ed.). Emergency Management: The American Experience (4th ed., pp. 239-265.

Roberts, P.S., Glick, J.A. & Wamsley, G. (2020). The evolving federal role in emergency management: Policies and processes. In C.B. Rubin (Ed.), Emergency management: The American experience (pp. 239-266). Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Sanders, M. (2023). What’s Driving the Boom in Billion-Dollar Disasters? A Lot, Pew: Southeast Ocean News, October 12, 2023. Retrieved on March 8, 2024, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2023/10/12/whats-driving-the-boom-in-billion-dollar-disasters-a-lot?utm_campaign=2023-11-14+SFN&utm_medium=email&utm_source=Pew&subscriberkey=00Q7V00001pNHA7UAO

Sarkissian, A. (2019). Former DEM director opens disaster consulting shop. Politico, March 1, 2019. Retrieved on March 6, 2024, https://www.politico.com/states/florida/story/2019/03/01/former-dem-director-opens-disaster-consulting-shop-881471

Sheffi, Yossi (2015). The Power of Resilience: How the Best Companies Manage the Unexpected. The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

United States Department of the Interior, Indian Affairs (2024). https://www.bia.gov/service/tribal-leaders-directory#:~:text=On%20this%20page,Would%20You%20Like%20to%20Do%3F. Retrieved March 5, 2024.

Urby, H. and McEntire, D.A. (2021). A cadre of professionals: Credentialing emergency managers to meet the disaster challenges of the future, Journal of Emergency Management, Vol.19, No.6, pp 531-540.

Vaz, Andrew R. (2024). 21st Century Responsibilities for Public Servants: The Grand Exodus, PA Times, February 23, 2024.

Waldo, D. (1980). The enterprise of public administration: A summary view. Novator, CA: Chandler & Sharp.

Wanless, A., Stormer, S., Ripberger, J.T., Krocak, M.J., Fox, A., Hogg, D., Jenkins-Smith, H., Silva, C., Robinson, S.E., and Eller, W.S. (2023). The Extreme Weather and Emergency Management Survey, Weather, Climate and Society, page(s) 1113-1118, Retrieved https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-23-0085.1

Wart, M.V. & Kapucu, N. (2011). Crisis Management Competencies: The case of emergency managers in the USA. Public Management Review, 13 (4), 489-511. Retrieved on June 6, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2010.525034