4 Evacuation Theories and Practices: Case Analysis in Taiwan

Yungnane Yang, PhD

Author

Yungnane Yang, Professor, National Cheng Kung University (Taiwan)

Keywords

mudslide, evacuation, information, mobilization, inter-organizational collaboration

Abstract

The purpose of this chapter is to explore how evacuation can be effectively implemented immediately before or after disasters. The three-element model developed by Yang (2010) is used to discuss and to explore evacuation problems and solutions. These three independent variables include information, mobilization, and inter-organizational collaboration. Communities are the basic units of this evacuation study. However, communities require support from governments and NPOs (Non-Profit Organizations) since they might not have enough evacuation resources on their own. In-depth interviews were conducted to gather information for this chapter. Six community leaders, from both Tainan City and Nantou County, were interviewed. The six communities each suffered from mudslide and flooding. They all became exemplary disaster management communities and were recognized by the Taiwan government as such. Community M, which was affected by a mudslide, was the main focus of this paper, but the other 5 communities were also studied and compared. The results showed that information, mobilization, and inter-organizational collaboration were three key factors of determining effective evacuation. National policy, such as Taiwan’s SDPC (Self-reliance Disaster Prevention Community) policy, can facilitate evacuation information, resource mobilization, and inter-organizational collaboration.[1]

Introduction

There are different types of disasters that may occur around the world, including flooding, mudslides, landslides, wildfires, volcanic eruptions, and so on. Earthquakes might also take place with numerous aftershocks, which could cause building collapse, landslides, and mudslides (Yang, 2024). These events can be called disasters when people die or are hurt. For instance, there were at least 11 hikers who perished and many others who were wounded due to a volcanic eruption of Mount Marapi in Indonesia.[2]

Unfortunately, early warning information about the volcanic eruption was ignored. Similar tragedies have repeatedly happened after disasters. For example, such problems have occurred in the U.S., Japan, and Taiwan. These countries have had evacuation problems in the past and will be discussed in this chapter. In these cases, warning information and evacuation are necessary to prevent the loss of life.

The loss of life is not always the outcome of extreme natural events. No people were injured after a state of emergency was declared for volcanic eruption in Iceland.[3] No people died during the mudslide at Renai Township of Nantou County in Taiwan on August of 2023.[4] These cases suggest that evacuation plans have been implemented, including the sharing of early warning information, the mobilization of resources, and collaboration of many organizations. These three topics are the focus of this chapter.

Evacuation can be defined as the process of moving people to a safe place due to the likely negative consequences of disasters. Quarantelli (1980) defined evacuation as “the mass physical movement of people, of a temporary nature, that collectively emerges in coping with community threats, damages or disruptions.” Moving people to safe places and coping with disasters are logical aspects of evacuation definitions. Whether evacuations are temporary could be debated. For example, the modular houses for the September 21, 1999 earthquake were designed for one year but utilized for more than three years by victims of Nantou County in Taiwan.

In terms of evacuation definitions, four issues are often discussed. First, information and information processing including communication before and during evacuation are often explored. Second, there might be problems associated with asking people to move voluntarily. Third, the threats might be either short term (temporary) or long term. It could be short term if the focus is solely on the evacuation process. In contrast, the evacuation could be long term if the victims’ houses were destroyed permanently and/or if it is unsafe to reconstruct houses in that same location.

Finally, communities are often treated as the basic unit of evacuation definitions. However, community residents need assistance from governments and from nonprofit organizations (NPOs) before, during, and after disasters. This automatically suggests that inter-organizational collaboration is necessary.

There are many challenges associated with evacuations. Some residents might not want to be evacuated. In addition, there might be both over and under evacuation, which may cause the death of numerous victims. There could also be vulnerable individuals and institutions, such as the disabled or nursing homes for the elderly. These lives could be saved if evacuation is carried out in an effective manner. Therefore, evacuation studies are necessary. Key factors for effective evacuation must therefore be identified and/or studied. This chapter utilizes the mudslide caused by 2001’s Toraji Typhoon as a case study. It also seeks deeper analysis through the comparison of other cases. The chapter illustrates that information, resource mobilization, and inter-organizational collaboration are key requisites to effective evacuations.

Literature Review

There are three main evacuation problems discussed in this chapter. These include information, resource mobilization, and inter-organizational collaboration. Firstly, there might be no early warning information. Alternatively, the evacuation information might not be accurate, clear, or timely. In addition, the evacuees might not be able to perceive the seriousness of evacuation information. Secondly, the necessary evacuation resources might not be properly planned, organized, mobilized, and used. This could limit the ability of people to leave a dangerous hazard or location. Thirdly, related evacuation related organizations might not collaborate with each other. This could lead to a chaotic situation and may result from a lack of incentive, willingness, ability, or capacity to coordinate (Robertson, 1996).

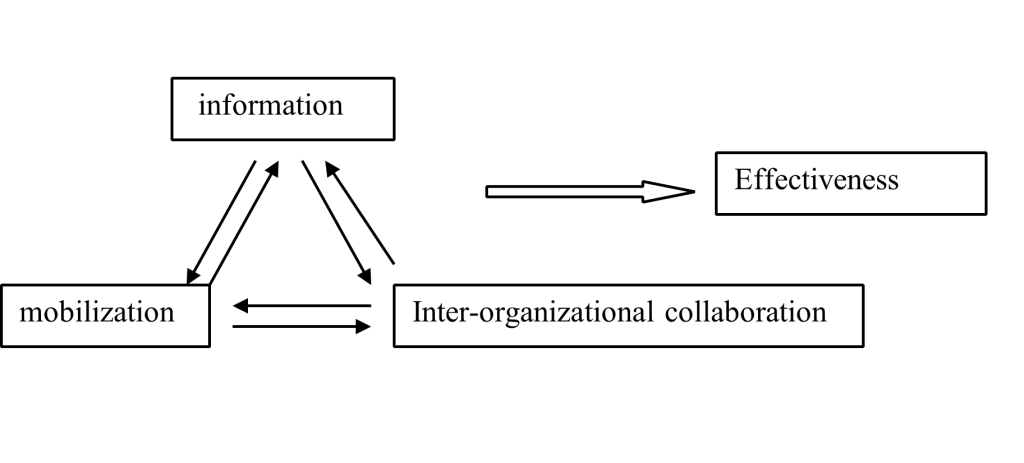

With this in mind, the purpose of this chapter is to explore evacuation effectiveness through the three-element model developed by Yang (2010). The three-element model (shown in Figure 1) will be discussed in the following pages. This approach is based on a prior study of evacuation problems (Yang, 2010). Two books and two research papers have been published by the author on this research framework and model (Yang, 2022; 2020; 2016). This work found that the model is both theoretical and practical since it could be used to explore evacuation solutions and/or suggestions of improving evacuation effectiveness. The model incorporates some of Bernstein’s (1978) arguments. He outlined that social and political theory ought to be empirical, interpretive, and critical. Many evacuation cases introduced in this chapter can be analyzed and explained by using this model.

The Three-Element Model

The three-element model was originally developed for the September 21, 1999 earthquake which happened in Nantou County of Taiwan (Yang, 2010). The focus was originally on search and rescue in disasters. But the model was used and applied to different disasters such as nuclear accidents, flooding, mudslides, and other events (Yang, 2016; 2020; 2022). Three independent variables, including information, mobilization, and inter-organizational collaboration, are presented in Figure 1. Clear and accurate evacuation information, which was the evacuation guidance, should be identified and processed in order to have effective evacuation, which is defined as needs of evacuees and efficiency of evacuation information processing.

Related and needed evacuation resources should also be mobilized following the distribution of clear and accurate evacuation information. Organizations, including central or federal governments, local governments, non-profit organizations, and communities possessing important resources must to collaborate with each other to achieve evacuation effectiveness (Yang, 2020; 2022). As can be seen by the double headed arrows, these three variables on highly interdependent. This model describes the dynamics and interactions of these variables. Information could have effects on resources mobilization. And resources mobilization could have implications on evacuation information.

Evacuation effectiveness, as a dependent variable, could be defined and measured in terms of the fulfillment of needs and efficiency, which were used as the two main indicators of effectiveness in this paper. Needs could be operationalized as food, clothes, and safety that evacuees must have. Otherwise, residents or evacuees might not be able to survive. And needs should be met in a timely manner. In addition, this model explores whether information, resources mobilization, and inter-organizational collaboration meet the needs of residents needed to be evacuated. Therefore, it is important to elaborate on information processing, resources availability, and inter-organizational collaboration based on the evacuation needs. Whether or not the evacuation needs were satisfied timely and/or efficiently is also implied in this model.

The term, needs, has been discussed in the field of organizational behavior. It meant that evacuees had basic needs in evacuation (e.g., in this case, safety and physical well-being) (Maslow, 1954; Herzberg, 1968; Alderfer, 1972). And these needs can be influenced or changed by information processing (Salancik and Pfeffer, 1977; 1978). For example, residents might not know the seriousness or risks of the early warning evacuation information unless the information was clearly perceived. This suggests that there could be a priming effect on residents’ attitudes through information processing. In other words, residents’ attitudes might be changed or influenced by training and education, which is also related to resource mobilization and inter-organizational collaboration.

Following up on these topics, Kuligowski and Gwynne (2009) argued that there was a need for behavioral theory in evacuation modeling. The three-element-model, which was mainly from the field of organizational behavior, could be the answer. Four levels, including individuals, groups, organizations, and environments, could be integrated into the three elements. For example, information, which is related to perception and cognition, is related to an individual level analysis of human behavior. And this individual perception might also be affected by interaction (groups), organizations, and environments including inter-organizational factors.

In order to better understand this three-element model, related literature was reviewed since it could be treated as a conceptual and/or theoretical framework. The goal of this literature review was to explore how evacuation information, resource mobilization, and inter-organizational collaboration could improve effectiveness. During the review of the literature it was determined that the research framework has been used in 5 master theses (Munkhtuya, 2018; Dlamini, 2020; Cyprien, 2021; Neyzsa, 2023; Ndayirata, 2024). These studies indicated that the model or the research framework was applicable and easy to be understood. Additionally, the three-element model could be used to explore evacuation problems and provide solutions.

There have been plenty of evacuation studies in the past (Thompson, Garfin, and Silver, 2017). Evacuation has been studied in a cross-disciplinary way by including building collapse, transportation, communication, wars, and disasters (Kuligowski and Peacock, 2005). There were also evacuation studies from different perspectives based on hurricanes, wildfire, flooding, earthquake, tsunami, and so on (Yang, 2020; 2022; Baker, 1991). The three-element model was adopted since it could be used to integrate different perspectives as shown in the following discussion of this section.

The literature has has concentrated mainly on mudslides and flooding but other cases related to disasters can be compared. This is because the model could be applied to many different kinds of disasters. For example, three cases could be explained. Firstly, there was a case related to evacuation where a young school teacher died by re-entering her apartment building after a 7.2 magnitude earthquake on April 3rd of 2024 in Hualien County of Taiwan. She wanted to save her pet cat and ignored the possibility of earthquake aftershock. Secondly, Doyle (2017: 10-11) indicated that there were about 100 people that died in the evacuation process during 2005’s Hurricane Rita. Thirdly, Rodríguez, Quarantelli, and Dynes (2007) pointed out that many people survived the 9/11 terrorist attack because of proper and instant evacuation arrangements. It has been argued that the terrorist attack on the twin towers has helped make today’s skyscrapers safer.[5]

The three examples mentioned above illustrated the importance and problems of evacuation information, resource mobilization, and inter-organizational collaboration. Early evacuation information was necessary to remind residents of the risk a hazard or disaster possess to them.. Proper evacuation may include who should initiate evacuation along with when and how people should be moved to safe locations. . Such evacuation issues and problems have been witnessed in many countries. Evacuation studies may provide possible solutions for stakeholders. For instance, Fu, Wilmot, Zhang, and Baker (2007) found that residents were more likely to be evacuated under mandatory than voluntary evacuation. But there were issues and/or problems relating to information, resources mobilization, and inter-organizational collaboration and these variables need to be discussed further.

In order to have deep analysis and discussion, the author believed that the research framework shown in Figure 1, which was simple and applicable, could be used to organize related literature on evacuation. This model was selected because all evacuation cases in this chapter could use the model to explore evacuation effectiveness. For this reason, related literature was arranged based on the three independent variables.

1. Information

Early warning information has been described as the key for evacuation effectiveness. Evacuation failures have often been related to information. Hurricane Katrina resulted in the death of more than 1,800 people. First, some victims might not have known they lived in dangerous areas and/or places with high risks of flood (drowning) and strong wind. Second, some might not have been sensitive to evacuation information due to lack of experiences and/or knowledge. Third, some bureaucrats and residents might have downplayed the seriousness of the storm, and therefore did not value warnings. Evacuation information was not issued clearly by government bureaucrats. Stakeholders and citizens were not ready to deal with the disaster.

Hurricane Rita also illustrated that many government bureaucrats and community residents didn’t expect a terrible evacuation process (Doyle, 2017: 10-11). More than 100 people died during the evacuation, which was not relevant to Hurricane itself but traffic related issues. Similar problems happened in the evacuation process of 2011’s East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. More than 100 people, mostly severely ill patients, died in the evacuation. These cases point out the safety issues of evacuation orders and processes.

Thus, there might be two problems for early warning information. First, information may not reach the at-risk residents. Second, residents with disadvantaged situations such as poverty and lack of connection with communities may not have access to an evacuation information systems. These resources were usually owned by different organizations such as social work, public health, and disaster rescuing organizations. Inter-organizational collaboration was necessary to improve information sharing.

As these cases demonstrate, evacuees had to perceive and understand their risks and either voluntary or involuntary evacuate. Two basic questions had to be identified. First, what evacuation information did possible victims need? Second, did evacuees understand what needs they had and how to fulfill them? For the first question, people needed to know when, where, why, and how to evacuate. They needed to receive education and training from government bureaucrats.

For the second question, Yang (2020: 51~76) asserted that evacuation information included contents, channels, and platforms. In other words, languages, words, photos, and messages could be treated as evacuation information. This information should be shared so that behaviors or actions can be taken to reduce risk. Also, channels were described as ways of disseminating information such as using traditional or social media. Platforms, which were treated as important policy instruments, were used to make connection and inter-organizational collaboration as Ansell and Gash (2018) proposed. Platforms would be discussed in the session of inter-organizational collaboration. These were the ways residents got access to information of which they were familiar and could accurately perceive and understand.

Burnside, Miller, and Rivera (2007) found that information sources such as authorities, friends, visual imagery, and media, were vitally important in evacuation. This work implied that information could be further interpreted and disseminated by other sources like social media or multimedia. Preston (2015) used transmedia storytelling and transmedia terrorism to explain the information and media effect. Transmedia meant the combination of different media such as traditional sources plus social media. This was important since there might be differences for the words used and meanings explained when the disaster story was told in diverse or cross media. Transmedia could be used either positively or negatively in storytelling. It became transmedia terrorism when negative meanings were processed or used.

The main evacuation question in this literature was how evacuation information should and could be processed accurately and timely. The answer could be found by categorizing needs and enhancing education. The needs for evacuation information were different based on age, gender, ethnic groups, and so on. It was found that evacuation intentions (attitudes) were higher among females and older people (Morss, Demuth, Lazo, Dickinson, Lazrus, and Morrow, 2016). Research implied that aged residents and females might be more sensitive to evacuation information than young residents and males. Aboriginal groups, who mostly lived in mountain areas in Taiwan, were usually unwilling to evacuate, owning to their culture and affiliation with their lands. This might be one reason for the 2009’s Morake evacuation tragedy.

In another study, Thompson, Garfin, and Silver (2017) found risk perception to be a consistent positive predictor of evacuation behavior. It suggested that risk perception might be influenced by age, genders, and ethnic groups. In addition, evacuation behaviors were determined risk perception, which was caused by attitudes. It was believed that evacuation information may shape evacuation attitudes and behaviors. But, firstly, there must be evacuation information available for evacuees. Secondly, the evacuation information must be accurate and understandable. Thirdly, the evacuation information must be trustworthy when evacuees made their final evacuation decision.

Another publication by Rodrıguez, Dıaz, Santos, and Aguirre (2007) indicated that around 80% of disasters were related to weather events such as flooding, hurricanes, and landslides. Some weather events, such as rainfall and hurricanes, could be predicted through weather forecasts. The reported weather forecast was the information sources for weather event prediction. For instance, some unstable slopes and potential flood areas might be affected by rainfall. Therefore, weather forecast information could determine evacuation effectiveness. The processed information may include language, words use, and perception of community residents. Training and communication, focused on interactions among evacuees and bureaucrats, were necessary in evacuation process to bridge the gap of information asymmetry or misunderstandings. The purpose was to ensure the safety of evacuees or evacuation effectiveness through information.

There might be other problems of early warning, weather forecast, and information processing such as those that occurred in the Hurricane Katrina evacuation case. Firstly, the weather forecast information was usually about the temperature and precipitation. Mudslide, landslide, and flood were not meteorologists’ expertise. Secondly, weather forecast could be just a weather report. But it could also be integrated with early warning information to remind people of the potential for flooding. Thirdly, the combined information had to be distributed to those who need the information instantly through different media or networking platforms. Based on the three problems, the evacuation information and actions might not have been processed and arranged adequately for both Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita.

The situation mentioned seemed to imply that evacuation movements might be necessary for Hurricane Katrina, but might not be necessary for Hurricane Rita. There might not have been enough evacuation information released or perceived. That was why a mudslide victim complained that government officials did not issue evacuation order or warn them the mudslide in 2023’s case happened in Chiayi County of Taiwan (Yang, 2023a). The victim was waiting for the evacuation order instead of searching for mudslide information actively. Three more possible reasons were illustrated.. First, the victim might not have mudslide and evacuation knowledge. Second, there might be not have been enough evacuation education and training. People living in potential mudslide areas should learn or be trained more about mudslides. Third, the victim’s community was not well organized to respond to mudslide.

As can be seen, evacuation information often includes messages of potential risk and risk level on specific time and at specific areas. Quarantelt i(1980, 100) stated that evacuation information should include warning, withdrawal movement, shelter, and return. But these recommendations might not be enough. Turner, Evans, Kumlachew, Wolshon, Dixit, Sisiopiku, Islam, and Anderson (2010) proposed the need to communicate evacuation information to vulnerable populations before, during, and after all-hazards emergencies. This means that evacuation messages such as evacuation orders might not be clear enough for evacuation. There might be evacuation information asymmetry or perception differences between issuers and receivers. Communication, including training and education, is therefore necessary for vulnerable populations. It implies that evacuation orders were unlike commands, which could force residents to leave.

In other words, there might be risks in the evacuation process. Evacuation was dependent on the characteristics of disasters and whether evacuation route and shelters were known and available. But there might be information asymmetry between evacuees and government officials who issued the evacuation orders. Therefore, resource mobilization, which was the focus of next section, is necessary.

2. Mobilization

Mobilization is a concept that refers to deploying necessary resources for evacuation such as transportation tools as well as food and water necessary for assisting evacuation based on known situations. But what resources are needed by evacuees had to be studied in terms of types of disasters. The easiest ways were to explore resources used in the past disaster cases. The problems were that there might be different scenarios related to different disaster cases. That was why there was over evacuation for Hurricane Rita’s after Hurricane Katrina. These cases suggest that evacuation needs and resources might be altered due to the unexpected situations. Evacuation resources, including human resources, material supplies, and budgets had to be mobilized based on available and accurate evacuation information (Yang, 2020: 83~110). For example, drivers and cars may need to be mobilized in a short time to assist the elderly to evacuate. And these resources have close linkages to evacuation training and transportation.

Dixit, Wilmot, and Wolshon (2012) stated that having evacuation plans might facilitate evacuation. Such plans could be treated as resources invested in evacuation. But, there are two ways of mobilizing evacuation resources. One was from top to down and the other was from bottom to up. Top down approaches meant that government authorities – either central or local ones – were in charge. Down up meant individuals or local communities were responsible. In this situation, it was assumed that individuals and community residents knew their needs better than governments. But, some residents might not have evacuation knowledge. It also implied that individual or community resources could be explored or mobilized through education. For instance, military mobilization might be efficient in case individual or community needs could be clearly identified. Taylor (2019) pointed out the importance of mobilizing military medical resources and general medical resources in disasters.

Keeling and Wall (2015: xxi-xxii) introduced the importance of nurses’ roles, including evacuation triage, physical and psychological care, screening measures, case findings, vaccinations, monitoring, disease surveillance and prevention in disasters. Their study implied that evacuation resources had to be designed and acquired before disasters. Evacuation technology, including information systems required for inter-organizational collaboration, is needed in order to have effective evacuation. For example, we could disseminate information and mobilize resources instantly through social media. Bourque, Siegel, Kano, and Wood (2007) suggested that “vulnerable” populations, such as women, children, the elderly, undocumented immigrants, underrepresented groups, and the poor, were differentially affected by disasters. It was because they had different evacuation needs.

For example, the elderly might not be able to drive a vehicle or move easily. This suggests that early resources investments to assist vulnerable populations were important to facilitate evacuation. This argument was consistent with the 2011’s nuclear and tsunami event in Japan. Tanigawa, a doctor that specializes in radiation, found that medical resources such as oxygen masks for transportation were not properly designed during the evacuation process of Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. Therefore, more than 100 elderly and severely ill patients died (Tanigawa, 2012). Patients died not because of nuclear radiation or the event itself, but because of improper evacuation arrangements (Yang, 2016). This often affects those in particular races, classes, and ethnicities due to inequality problems (Bolin, 2007).

As can be seen, there must be motivation for evacuees and local authorities to explore evacuation resources based on evacuees’ needs. There must be more preparedness of necessary evacuation resources. Otherwise, evacuation needs might not be satisfied. The incentives might be depend on government officials’ or evacuees’ initiation or motivation. But the considerations were mostly based on evacuation orders. The higher the possibility of issuing evacuation orders, the higher motivation of mobilizing necessary evacuation resources. Quarantelti (1980, 101) pointed out that local authorities might be reluctant to issue evacuation orders because of negative social economic consequences. For this reason, higher-level authorities such as central governments might have more resources, which could be used to assist local authorities or community residents to evacuate.

For example, these resources could be budgets, which could be used for training or education, human resources for assisting evacuation, and transportation preparation. Platforms, which were applied in different fields, could also be treated as resources since they could bring representatives from different organizations for the purpose of collaboration. As mentioned earlier, resources were mainly dominated by organizations. Nambisan (2009) proposed that there were three different kinds of platforms for collaboration. These were exploration platforms, experimentation platforms, and execution platforms. Exploration platforms might be just for the purpose of exploration, which was like (evacuation) policy formation. The experimentation platforms could be like (evacuation) policy planning. The purpose was to test the feasibility of the evacuation. Execution platform, like policy implementation, could assist the coordination and networking of executing evacuation.

But, in practice, the three kinds of platforms were interrelated. The focus group design for research purposes was the example. The focus group members or stakeholders could be gathered to explore specific problems to form exploration platforms. In addition, these platforms can be used to mobilize related resources. With consensus, the focus groups could be turned into experimentation and execution platforms.

3. Inter-Organizational Collaboration

Networking can be the operationalization of inter-organizational collaboration. Platforms can facilitate both networking and inter-organizational collaboration. Successful evacuation is often the results of inter-organizational collaboration among federal(central) governments, local governments, and NPOs. The literature on evacuation illustrates that resources could be mobilized through (inter-organizational) networking. So, networking, could also be treated as resources. Kiefer and Montjoy (2006) pointed out that successful evacuation was depended on private conveyance and networking based on the 2005’s Hurricane Katrina’s case. The private conveyance and networking could be categorized to be mobilization (resources) as well as inter-organizational collaboration. This could include employees from private, non-profit, and public organizations involved in networking. In this study, this implied informal inter-organizational collaboration. In addition, there were many related organizations with different levels of evacuation knowledge and information. But these organizations might not cooperate closely with each other in evacuation.

Perry (1979) stated that evacuation is an important tool in the hands of authorities. It implied that governments bear the responsibilities of evacuation. But authorities could mean central (federal) or local governments. NPOs and communities could likewise play active roles on evacuation policies. Also, residents’ risk perception might affect evacuation effectiveness. In order to reduce perception differences, information and information processing were important. However, information might be costly. The costs could be reduced through information sharing such as creating platforms. Ansell and Gash (2018) treated platforms as policy tools or strategies of collaborative governance, which could be explained as inter-organizational collaboration in this chapter.

Nambisan’s (2009) three types of platforms were the examples of using platforms as policy tools or collaboration strategies. Forums, meetings, conferences, partnership planning, and networking were the implementation of platforms. Platforms could be arranged or used electronically or physically. But the problems were the motivation and commitments of the forum participants. It was also dependent on whether the participants were willing to contribute to the platforms, which could promote and facilitate policy goals. Yang (2020: 111-136) used incentives, willingness, ability, and capacity developed by Robertson’s conceptual framework to explore inter-organizational collaboration (Robertson, 1996).

Incentives for inter-organizational collaboration could be monetary or non-monetary terms. Incentives could be used to move stakeholders and related organizations to work with each other on evacuation preparedness. Willingness was important since it was related to belief, trust, and commitments. Ability was defined as the basic knowledge and skills required for evacuation. Capacity was described as institutions including formal and informal constraints, which could facilitate the evacuation implementation.

Waugh (2007) argued that Department of Homeland Security (DHS) was created to react to the 9/11 terrorist attack. And FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency) was moved under DHS. But core values were different between terrorism and natural disasters. There was more political consideration or national security on terrorism. Missions behind DHS and FEMA were different. DHS’s mission was on terrorism and/or national security. Evacuation policy for 2005’s Hurricane Katrina was likely affected. It implied that the FEMA reorganization might impacted the above 4 factors of inter-organizational collaboration among FEMA and other organizations.

McEntire (2007) proposed that emergency managers played important roles in dealing with disasters. And he also insisted that outside organizations could bring resources for local authorities. It was because local emergency management organizations usually reacted to disasters immediately. Compared with central or federal governments, local authorities might have fewer resources (e.g., budgets) for new or emerging policies. Many local authorities relied on the federal government, especially FEMA’s assistance during the Hurricane Katrina and Rita cases.

Yang (2010) found that Nantou County Magistrate became the “emergency manager” during the 1999 9/21 Earthquake, which was one of the largest earthquakes in Taiwan’s history. The Magistrate played the role of information processing, resources mobilization, and inter-organizational collaboration. The Magistrate himself used radio to broadcast the earthquake information and asked for resources such as water, food, and tents. This occurred because all communication facilities such as electricity, telephone, and television were shut down by the earthquake. He also had to coordinate with central government agencies such as the military and district attorney to deal with emergency problems caused by the earthquake. It was necessary to have local, national, and international organizations involved in the rescue and recovery in such a large-scale earthquake. Similarly, large-scale evacuation required a lot of efforts and resources to be involved in resource mobilization, which necessitated complex inter-organizational collaboration.

Many countries have an independent organization to coordinate across departments’ and organizations’ resources such as the U.S. (FEMA), Japan (A commission handled by Disaster Prevention Minister under Prime Minister), and Turkey (AFAD, Disaster and Emergency Management Authority. But the disaster management agency under central or federal government was often the organization to form disaster management policies and making policy planning. Policy implementation is mostly handled by local governments under guidance of central government.

Sorensen and Sorensen (2007) insisted that evacuation was a community process, which was affected by technology and social changes. It was like the development of self-reliance community policy development in Taiwan. Their study found that community involvement could have a mitigation effect on disasters after cases of earthquake, typhoons, mudslides, and flooding in Taiwan. One finding was to train or educate vulnerable communities to have the ability of self-rescue, self-reliance, and community mutual assistance. And the self-reliance community policy development process was related to evacuation information, evacuation resources(mobilization), and inter-organizational collaboration.

Community could be regarded as the basic unit of evacuation in many studies. There are human and non-human evacuation resources within communities. Inter-organizational collaboration is necessary to mobilize community evacuation resources. Firstly, evacuation resources for communities might not be enough to react to large scale disasters. Secondly, community evacuation resources might not be used effectively. Community leaders and/or residents might have coordination problems of mobilizing evacuation resources. Thirdly, it was important to examine whether there was external resources or support. And it required inter-organizational collaboration to assist communities before, during, and after evacuation. Community leaders could also play the role of emergency manager as mentioned above to mobilize resources and to build platforms for inter-organizational collaboration.

For example, dealing with disasters became missions of Taiwan military including rescuing and evacuation assistance after 2009’s Typhoon Morakot. The purpose was to improve the evacuation problems which happened in Typhoon Morakot such as the shortage of human resources. The military provided necessary resources to assist communities with needs for evacuation resources. Drabek (2007) proposed that the key for emergency management was the coordination of community processes. The goal is to get resources organized from different organizations through coordinators, who played an important role during evacuation processes. By doing so, both structure and processes should be designed or included in coordination. Inter-organizational collaboration might need a lot of efforts to enhance coordination. It was found that community officials were often treated as the most trustworthy information sources (Paul, 2012; Cahyanto, and Pennington-Gray, 2014). But, as mentioned above, communities needed policy assistance from both local and central governments.

Based on the discussion above, it was clear that the three-element model developed by the author (e.g., information, mobilization, and inter-organizational collaboration), could be used to develop an evacuation model. The model could be used to explore evacuation problems and to provide evacuation solutions. And the three independent variables were interrelated with each other. Mobilization had to be based on key evacuation information to fit the needs of evacuees. Platforms could facilitate information processing, resources mobilization, and inter-organizational collaboration. But the focus should be the evacuation effectiveness, which included needs and efficiency of the stakeholder.

Methodology

This study relied on qualitative research by using in-depth interview and secondhand data such as research reports regarding the disaster cases. The purpose of this chapter was to explore general evacuation principles. The firsthand data, collected through interviews. was from Taiwan’s community cases. Interview questions were designed and conducted to realize the real evacuation process and problems. There were 6 community leaders interviewed by the author as Table 1 shows. Many of them were interviewed more than twice. And, it should be pointed out that these conversations were not simply an interview. There was a lot of discussion between the author and the interviewees. The community codes were used based on their first characters’ pronunciation in Chinese. In this way, the author could easily identify the communities although readers might not know the exact communities. Community leaders’ personal information could be protected.

Community M experienced a mudslide after Typhoon Toraji in 2001, which was related to the September 21, 1999 earthquake (Yang, 2024). The author helped M Community develop a community disaster management team in 2002 and the author and the M Community Leader became friends and kept working on issues of disaster prevention education and community recovery. Therefore, the main focus of this chapter began from M Community’s mudslide. And the author expanded cases with flooding and mudslide at the other 5 communities. The author got to know H Community Leader in 2021 and became friends. Both Community H and M suffered from 2001’s mudslide. 9 M Community residents died at the 2001’s mudslide. No resident died for Community H owing to their high consciousness of disaster response led by the community leader. The other 4 communities, which suffered from flooding and mudslides, were all exemplary disaster prevention communities recognized by the Water Agency of Taiwan government.

Interview question design was based on the three-element model. The approach was meant to explore evacuation information, resources mobilization, and inter-organizational collaboration. All 6 community leaders had representativeness for the interviews since they had experiences of leading residents to go through disasters. Stallings’ (2007) argued that criteria including timing, access, and generalizability should be considered regarding disaster case studies. The criteria were used by the author for choosing the interviewees. The Q and B Community leaders did very well on evacuation. Firstly, they had a lot of real experiences on flooding currently and in the past. Secondly, the two communities were trained and became exemplary communities. Thirdly, residents from the two communities actively participated in the evacuation training and education activities.

The author tried to make acquaintance with the community leaders first before relevant interviews. Three community leaders, including Q, B, and M communities, were invited to give talks about their evacuation process. Two of them, including those from SJ and H, were interviewed face by face. The leader of SS community was interviewed over the phone. With the exception of M community, the other 5 communities’ stories were about their response to disasters after trainings. The M Community had disaster response trainings after 2001’s Typhoon Toraii. The author has interacted with interviewee M more than 50 times since 2002. It was because the M community was hurt seriously by mudslide caused by 2001’s Typhoon Toraji. There were 9 people who died int M community. 4 out of the 9 residents have yet to be found. The author, as a principal investigator, was subsidized by the central government to assist M Community to organize their Community Disaster Management Team (CDMT). For this reason, the author was able to understand the evacuation process of M community in 2001’s mudslide.

There were around 60 residents who joined CDMT at the M Community. There were only 5 members of CDMT in 2020 for the community. Owing to the controversial development of the detention park nearby M community, the author re-entered M community and conducted a series of forums. Four forums related to community disaster prevention issues were organized by the author from 2020 to 2021. Disaster prevention instead of tourism development goals were reached among stakeholders. The CDMT members at M Community were increased to 20 under local governments’ supports in 2021.

The three communities, including Q, B, SJ, all suffered from flooding for decades. But these communities have been evaluated as excellent Self-reliance Disaster Prevention Communities (SDPC) under the Water Agency policies of the Ministry of Economics. Two master theses were written based on the Q Community’s successful story (Pongen, 2022; Wang, 2022). The term, SDPC, was from CDMT and was used around 2010. The concept was similar between CDMT and SDPC. Therefore, the two terms could be used interchangeably. The H and SS Community were trained by the Agency of Rural Development and Water and Soil Conservation of the Ministry of Agriculture (ARDSWC). Both communities worked very well in terms of disaster prevention and evacuation practice. Each community had his own evacuation story.

|

Community |

Location |

Date of interview |

The event year |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Q |

Tainan City |

2020/10/20 |

2018’s Heavy rain (flooding) |

|

B |

Tainan City |

2023/6/1 |

2018’ s Heavy rain (flooding) |

|

SJ |

Tainan City |

2021/7/27 |

2018’ s Heavy rain (flooding) |

|

M |

Nantou County |

2021/7/20 |

2001’s Typhoon Toraji (mudslide) |

|

H |

Nantou County |

2023/9/12 |

2001’s Typhoon Toraji (mudslide) |

|

SS |

Nantou County |

2021/7/13 |

2009’s Typhoon Morakot (landslide & mudslide) |

Solution

The three-element model could be used both in diagnosing evacuation problems and providing solutions and making discussion. Therefore, the three independent variables were arranged to be the subtitles of this section. Solutions were provided and explained by research findings. It required assistance from governments and NPOs, although communities should play a key role in evacuation. Problems and solutions could be understood through the following discussion.

1. Information

Regarding Typhoon Toroji in 2001, there were weather reports from the Meteorology Agency that the typhoon was coming on July 29. It was reported that Typhoon Toraji had passed over the Central Mountain Range at 10:00 pm of July 29. There was no strong wind and just a little drizzling at 6:00 am on July 30. It was observed that the river level was only one half of water at that time as explained by the M Community Leader. The M Community Leader got an evacuation notice that a barrier lake was formed from local police authorities around 6:30 am July 30 of 2001. But the M Community Leader was unsure about whether there would be mudslide. This was due to the fact that he didn’t have the mudslide experiences and had no related training before 2001. He, therefore, drove with his neighbors to a nearby bridge and checked with the river water flow around 6:40 am.

Then, the M community leader found the river flow increased unusually. So, he reported to the police station about the risk of mudslide at 7:00 am. He left the bridge and went back home around 7:10 am and felt that he had to evacuate. Then he went back home and did two things. Firstly, he asked his family member to get in cars to evacuate. Simultaneously, he went to knock on his neighbor’s doors to warn them to evacuate. But one household did not respond. He then drove his family out of home to a safe place. The M Community suffered from mudslide within 10 minutes after they left. The levee was broken around 7:45 am. Firefighters with boats, excavators, and helicopters arrived at M Community to complete search and rescue.

Unfortunately, community residents and government officials did not have real experiences of mudslide before 2001. In addition, the evacuation order was issued very late and with unclear description. The evacuation perception of community residents was affected by the late evacuation and vague information. There was only 30 minutes left for community residents to prepare and evacuate. It was possible that some M Community residents died because they didn’t receive any warning or evacuation information. Or, they just didn’t know they should evacuate. It was also possible that information technology and media were not sufficiently developed in 2001. Furthermore, the CDMT policy was not developed and implemented until 2002. The SDPC policy appeared around 2010.

The H community monitored rainfall through a measuring cylinder given by ARDSWC. And the H community leader began to share the rainfall information with ARDSWC and M Community in 2021 after the author’s intervention. The evacuation orders were usually issued by ARDSWC. The Q community leader explained that he could read, understand, realize, and predict rainfall based on the weather forecast in 2021. He would consult with the city government disaster management center and make evacuation decisions. The SS Community leader had sensitivities of flooding based on her observation of rainfall and river flow. She would make the evacuation decision based on her observation and ARDSWC’s training. The other community leaders got weather forecast information and made evacuation preparation for themselves.

Based on the above stories, there should be no problem currently in Taiwan for most communities regarding early warning information, evacuation information, evacuation communication, and evacuation training. It was reported that no community residents died of mudslide caused by Typhoon Khanun in early August of 2023 at Ren’ai Township, Nantou County, Taiwan. Community residents were led by the community leader and evacuated to safe places under the SDPC policy. Dixit, Wilmot, and Wolshon (2012) found that having evacuation plans might facilitate evacuation. Training and education, could be parts of evacuation plans, were the keys to reduce the risks of evacuation information asymmetry as mentioned above.

2. Mobilization

Evacuation resources had to be mobilized through governments, communities, and NPOs. First, community evacuation resources could be mobilized through training. Second, outside resources could be mobilized and linked with communities through training and networking between communities and governments. The SS community leader was persuaded by ARDSWC officers to join the training courses of community disaster prevention in 2007. She joined the training two times both in 2007 and 2009.[6] She explained that she didn’t want to join the training originally. She did not know she needed mudslide and evacuation knowledge. She finally joined the training after receiving several invitations from ARDSWC officers. She realized that mudslide might be caused by heavy rainfall after the training. She became concerned that the heavy rainfall might destroy their farm lands before training. In other words, she was able to perceive the risk of mudslide after the training.

Later on, Typhoon Morakotbrought heavy rainfall in middle and southern Taiwan at mid-night of August 9, 2009. Owing to the training arranged by ARDSWC, the SS Community Leader felt that there might be something wrong because of heavy rainfall. She got up quickly to try to warn 100 community residents to evacuate. She had more knowledge about mudslides because she was trained as a specialist of community disaster prevention by ARDSWC. She, together with her husband, began to communicate with policemen and firefighters to assist community evacuation. She also tried her best to communicate with community residents to evacuate. One resident was not willing to evacuate at the beginning. The resident finally agreed to evacuate after communication and persuasion.

The resident’s house was destroyed by mudslide 5 minutes after they left the area. The community leader might not have had the inclination to initiate evacuation and disseminate evacuation information without the ARDSWC’s training courses. Based on her training, she also knew how to mobilize necessary resources such as asking police and firefighters to assist the evacuation. Also, ARDSWC was willing to invest disaster prevention resources for the community. However, the situation turned to be a tragedy for the other community located in southern Taiwan.

The Xioalin Village (community) leader rejected the evacuation order issued by local officials in 2009’s Typhoon Morakot in Kaohsiung City of Taiwan. More than 400 community residents, mostly aboriginal people, were buried by landslide after the evacuation rejection. he judge argued that local officials should be held accountable. Local authorities had to take further actions after the village chief’s rejection. In other words, the tragedy might be caused by risk perception and education or training problems of Xioalin Village based on the above discussion.[7]

3. Inter-Organizational Collaboration

Inter-organizational collaboration should be promoted to support evacuation. By doing this, incentives and platforms had to be created. Inter-organizational collaboration was institutionalized under the SDPC policy. The Q, B, SJ, and H communities were all evaluated by central government agencies as exemplary ones under the SDPC policy. The Q, B, SJ communities were awarded from 3,000 to 6,000 USD for their excellent performance. The awarded money could be used to visit and learn from the other communities’ experiences also. The money would also allow community residents to be trained more about early warning and evacuation. The training purpose was to minimize or reduce the risk of death and damages. Based on the training, the four communities would evacuate vulnerable residents firstly such as aged and handicapped.

The H community leader worked actively on disaster management practice. The community was supported financially by both ARDSWC and Community Development Association. The above-mentioned communities shared similar characteristics, which were mostly the results of inter-organizational collaboration. First, they were trained by professional groups, which were sponsored by governments and were mostly from universities. Second, the community leaders with their team members had high motivation of working on community disaster prevention practice. Third, the four communities had had high risks of flooding (Q, B, SJ) and mudslide (H) before.

Behind the excellent performance of these communities, important roles were undertaken by central government agencies, local government agencies, and non-profit organizations (NPOs). Central government agencies included National Fire Administration (NFA), Water Agency, and ARDSWC. These three agencies were assigned to assist and develop community disaster prevention policy. Local governments, especially fire departments, were responsible to promote and/or implement community disaster prevention policy. The author was told by a fire chief that not all community leaders were interested in becoming SDPC.

Professional groups, which were under universities, implemented the SDPC policy and assisted communities to improve their capacity for disaster prevention. In reality, there were many different organizations collaborating with each other to implement SDPC policy as mentioned above. Put differently, the performance of community disaster prevention was the result of inter-organizational collaboration. Community leaders’ initiation and commitments were important. But inter-organizational collaboration outside of communities was also indispensable. Motivation and commitments from these organizations were important in order to assist communities to perform excellently.

Based on the above discussion, the three-element model, including information, resources mobilization, and inter-organizational collaboration, could be used to explore problems of the evacuation effectiveness for different cases. Solutions could also be discussed based on the three-element model.

Discussion and Implications

In order to achieve evacuation effectiveness, information, resources mobilization, and inter-organizational collaboration were the three keys based on the above discussion. Therefore, the following discussion is based on the three independent variables and previous findings regarding the problem of evacuation. Both theories and practices were discussed in the following section. Recommendations for future research and practitioners are also provided.

1. Information

Early warning information had to be processed accurately and timely to meet the needs and save the lives of community residents. Based on the M community leader’s explanation, the early warning information was issued by government agencies. But the information was not perceived precisely and/or instantly. There was information asymmetry between early warning information issuers and perceivers. Therefore, information and information technology could be further developed to promote evacuation effectiveness. There were variety of ways of developing evacuation information in order to bridge the gaps between evacuees and authorities. Evacuation information was the first key to improve evacuation effectiveness.

But the information should be designed regarding how evacuation information could reach residents and be evaluated in time. Therefore, Yang (2020, 51-82) proposed that contents, channels, and platforms should be emphasized. Contents were about the use of words, languages, and images. Channels were ways of disseminating evacuation information such as traditional media, social media, and transmedia. Platforms could be websites, line groups, and disaster management operation centers. But the information design should be based on evacuation needs of communities. The information design could be effective if it fits with institutional arrangements of communities (North, 1990).

The M Community’s evacuation story revealed the problems of evacuation information, which could not reach all community residents. In Particular, the evacuation information was not trustworthy. So, the M community leader went to check the river flow. Then, he realized the urgency of evacuation. It also implied that the deaths of community residents could be avoided through effective information processing. The SS community story gave us one solution or answer to the problems in M Community. Through training, the community leader could have had more sensitivity about evacuation information and was able to mobilize available resources to disseminate evacuation information. Therefore, more than 100 community lives were saved.

It was believed that there could be mudslide early warning information before a mudslide were to happen. If so, community residents had to be trained to be sensitive to early warning information. And they were willing to explore the early warning information actively. For example, accumulated precipitation and geographical conditions were important warning signs of evacuation as the Q Community saw. In addition, Thomas, Ertuˆgay, and Kemec (2007) proposed the importance of geographical information system, which might be helpful for making the evacuation decision. Technological changes and development (e.g., investment) could provide more detailed evacuation information.

But residents should be trained to perceive and/or understand the meanings of the warning information. In that case, government officials still bear the responsibilities of training residents to be sensitive to the early warning information. But the training willingness of community residents should not be ignored. Information perception might determine the effectiveness of evacuation. Evacuation orders issued by governments should be fully understood by residents. Therefore, Yang (2023a) proposed the development of early warning information, education and training, and community response teams (CDMT).

Evacuation guideline have been posted on official website under DHS.[8] But how the evacuation information could be further developed to fit the needs of potential residents, especially those who are vulnerable to disasters, is an important issue for both researchers and practitioners. Information needs could be further explored through classification and case study. For example, information needs might be different based on genders, ethnic groups, location, and so on. Information technology could also be researched and developed to facilitate evacuation information processing efficiently.

2. Mobilization

Based on the interviews of community leaders, many of them were sensitive and were able to evacuate successfully. It was mainly because successful training and educational activities were well mobilized inside and outside of these jurisdictions. It also indicated that evacuation resources could be mobilized inside and outside of communities. In order to reduce evacuation information asymmetry, training was an important resource and could facilitate communication as mentioned above. The SS community story provided us a great example of how to mobilize both inside and outside communities’ resources to improve evacuation effectiveness. But the evacuation effectiveness for the SS Community could be improved. This is likely the situation because the ARDSWC’s training was mainly on individual level, especially the community leaders. The Water Agency’s training was on community levels. It implied that the time of evacuation communication could be saved if more community residents have the similar training. But, of course, more training resources had to be invested. And community residents’ willingness of joining the training sessions were extremely important.

In contrast, the Xiaolin Village was a failure story. This might be because there was no training before the disaster for the community leader and residents regarding the landslide and mudslide. They didn’t have the sensitivities of evacuation or warning information. Another possibility is that resources were not mobilized or invested in community disaster prevention. Yang (2020, 83~110) proposed there were resources inside and outside communities. Resources could be calculated based on human, non-human, and financial resources, and resources could be mobilized through self-assistance, mutual-assistance, and public assistance (SMP).[9] The SMP model was originally from Japan. But the SMP model was widely used in Taiwan.

It is implied that self-assistance must come first. Each individual needed to have basic disaster and/or evacuation knowledge. Individuals could self-serve or rescue when reacting to disasters. Mutual-assistance came secondly in case self-assistance could not be done. Public assistance was the last resort – especially when public resources were not enough to deal with large scale disasters. In terms of the SMP model, there were plenty of resources could be developed especially self-assistance and mutual assistance. That is, training resources had to be mobilized.

However, the community disaster prevention resource mobilization was different between Taiwan and the U.S. NERT (Neighborhood Emergency Response Team) or CERT (Community Emergency Response Team) was developed in San Francisco or Bay area after 1989’s San Francisco Earthquake. The author joined the CERT training course in 2013 since anyone who was interested in CERT training courses could join. The CDMT or SDPC was only for community residents but not open to the public. CERT’s training was focused more on individual level, but CDMT was on community level. The CERT training program was more on rescuing, searching, medical assistance, fire safety, and psychological effect.[10] But the CDMT training courses included information (monitoring and weather forecast), rescuing, medical assistance, evacuation, and logistics. It might be because CERT was more earthquake oriented but CDMT was more flood or mudslide oriented.

Resources should be mobilized to fit the needs of residents based on their information needs. The gaps of information asymmetry could be bridged through related resource mobilization. For example, financial aid might be necessary for developing education and training programs for community residents or general residents. In addition, how evacuation resources could be distributed equally, efficiently, and transparently is an important evacuation concern for both practitioners and researchers. In many cases, inter-organizational collaboration is necessary since resources might be controlled by different organizations including central government, local governments, non-profit organizations, and communities.

3. Inter-Organizational Collaboration

The SS community leader was able to save more than 100 community residents in the 2009 flood. There were 3 reasons. First, she was trained to be the flood and mudslide specialist through ARDSWC’s training courses. Second, she had developed sensitivity to early warning information and was able to actively mobilize community residents to evacuate. Third, she was able to mobilize policemen and firefighters to assist SS community residents to evacuate under her networking with stakeholders. It implied that inter-organizational collaboration could be facilitated through evacuation policy. Taiwan’s SDPC was a successful example. Ansell and Gash (2007) pointed out the importance and conditions of collaborative governance. The conditions were incentives for participation, which was included in the four factors of inter-organizational collaboration as mentioned above.

They further proposed platforms to be important strategies and policy tools for collaborative governance (Ansell and Gash, 2018). For the excellent communities of performing SDPC, they were all the results of inter-organizational collaboration. But these communities’ initiation and active participation played a very important role as mentioned above. It could be stated that the collaborative platforms existed in central government agencies, local government agencies, NPOs such as universities and professional groups under universities, and communities. These organizations were willing to collaborate because they shared common goals.

The purpose of inter-organizational collaboration was therefore to promote information and resource sharing and to achieve evacuation effectiveness. Table 2 indicated the performance of the 6 studied communities. Motivation dealt with the community attitudes toward evacuation. Community leaders’ attitudes were usually the keys. Governments included both central and local governments. It was believed that the community performance on evacuation was mainly caused by attitudes of both community and governments. The evaluation was made by the author from level 1 to 5 subjectively based on the author’s interaction, observation, and understanding of these communities. 5 means high and 1 means low.

|

Community |

Motivation* |

Governments** |

Performance*** |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Q |

5 |

4 |

5 |

|

B |

5 |

4 |

5 |

|

SJ |

5 |

4 |

4 |

|

M |

5 -> 3 -> 4 |

5 -> 3 -> 4 |

4 |

|

H |

5 |

3-> 5 |

5 |

|

SS |

3 -> 5 |

5 -> 5 |

5 |

| *Motivation means community leaders’ motivation toward evacuation **Government means attitudes of bureaucrats toward community evacuation ***The performance level evacuation |

|||

Some columns with more than one number in table 2 indicated different stages’ evacuation attitudes. For example, the M community’s motivation was high originally because of the 2001’s mudslide. But the motivation was decreased to 3 in 2020 because no mudslide or disasters after 2001. Motivation became high again in 2020 because of training intervention in 2021. For the SS community, it was the ARDSWC officials who actively persuaded the community leader to have disaster prevention training since the community leader was reluctant to have the training at the beginning. The H community’s motivation has been very high but with little attention from governments. But government attitudes became high for H Community in late 2021. It might be because of the evacuation forum discussion organized by the author.

Both SJ and SS community had female leaders handling evacuation. It meant that female community leaders or selecting female leaders could be an beneficial evacuation strategy. It was found that evacuation intentions were higher among females and older people (Morss, Demuth, Lazo, Dickinson, Lazrus, and Morrow, 2016). It implied that there were different needs for information and resources based on gender and seniority. Or, males and young people might need more communication including education and training. And it could be developed as policy issues to create incentives for inter-organizational collaboration including central government and local government agencies. Further design of evacuation information and resources might be needed to satisfy differentiated needs. And, of course, it could include issues of both organizational or inter-organizational collaboration design.

Conclusion

As noted, this study found that early warning information was the first key and priority for evacuation effectiveness. The early warning information had to be accurate and instant in order to fit the needs of evacuees. For this reason, information technology could be developed and assist early warning information gathering and processing. The M community leader received the early warning information of mudslide but unsure the accuracy of the information. The M Community leader spent 20~30 minutes checking the river flow. Then, he believed and evacuated his family successfully. His neighbors died of the mudslide. He did try to knock on his neighbors’ doors but with no response before the mudslide. It indicated the problems between issuing and perceiving the early warning information.

The interviewed community leaders were able to perceive the importance of early warning information. It was because most community leaders had had related education and training before. They were sensitive to early warning information and they actively mobilized community residents to participate in the training and educational activities. Training and education could therefore be treated as resources, which should be mobilized to assist vulnerable communities. But human resources had to be mobilized to be involved in the training and education activities within and outside communities. The purpose was to train community residents to be sensitive to early warning information.

Experts such as mudslide professionals or academicians from outside could also mobilize or assist community leaders and residents to improve evacuation knowledge. Professionals and academicians could be from either government agencies or educational institutes. It implied the importance of inter-organizational collaboration. For this reason, incentives, ability, willingness, and capacity proposed by Robertson (1996) were important factors to facilitate inter-organizational collaboration. It indicates the importance of evacuation policy and/or platforms. Evacuation training and education activities could be platforms for inter-organizational collaboration.

Smith and Wenger (2007) argued that sustainable recovery, not just repairing and reconstruction, is necessary. These authors also implied that sustainability should be applied to studies about evacuation. In other words, we need to make sure the evacuation practice and knowledge are sustained. The purpose is to avoid evacuation mistakes and improve effectiveness. As for the 2009’s Typhoon Morakot case, many residents were successfully evacuated in mountain areas. And it was strongly suggested that these evacuees should not go back to mountain areas and work on overdeveloped farm lands. The Tzu-chi Foundation, an NPO, built permanent houses for victims. But some victims declined to live in the houses owing to culture, agriculture, and compensation factors (Chen, 2011, 87-99). These were also evacuation issues in future sustainable studies.

Overall, the three-element model proved to be a useful way of analyzing disaster cases in Taiwan. There were also lessons learned from these cases. Training might improve evacuation information processing. And it might improve evacuation resource mobilization and inter-organizational collaboration. The six chosen communities were all from Taiwan. It didn’t mean all communities in Taiwan were successful. The suitable explanation is that the performance of the six communities were more or less influenced by Taiwan’s SDPC policy. There might be communities which are not willing to participate and want to improve evacuation effectiveness. But the research findings and discussion might have evacuation implications for communities in different countries. It meant that the three-element model, as figure 1 showed, could be applied and explained in different country’s evacuation cases.

References

AL-Dahash, H., Thayaparan, M., Kulatunga, W.(2016). Understanding the Terminologies: Disaster, Crisis and Emergency. In P W Chan and C J Neilson (Eds.) Proceedings of the 32nd Annual ARCOM Conference. 5-7 September 2016, Manchester, UK, Association of Researchers in Construction Management. 2. 1191-1200.

Alderfer, C.P.(1972). Existence, Relatedness, and Growth. New York: Free Press.

Ansell, C., and Gash, A.(2018). Collaborative Platforms as a Governance Strategy. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 28. 1. 16–32.

Ansell, C., and Gash, A. (2007). Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 18:543–571.

Baker, E.J.(1991). Hurricane Evacuation Behavior. International Journal of Mass Emergencies & Disasters. 9. 2. 287-310.

Bernstein, R.J.(1978). The Restructuring of Social and Political Theory. PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Bolin, B.(2007). Race, Class, Ethnicity, and Disaster Vulnerability. In Handbook of Disaster Research edited by Rodríguez, H., Quarantelli, E.L., and Dynes, R.R. 113-129. NY: Springer.

Bourque, L.B., Siegel, J.M., Kano, M., and Wood, M.M.(2007). Morbidity and Mortality Associated with Disasters. In Handbook of Disaster Research edited by Rodríguez, H., Quarantelli, E.L., and Dynes, R.R. 97-112. NY: Springer.

Burnside, R., Miller, D.M.S., and Rivera, J.D.(2007). The Impact of Information and Risk Perception on The Hurricane Evacuation Decision-Making of Greater New Orleans Residents. Sociological Spectrum. 27. 6. 727–740.

Cahyanto, I., and Pennington-Gray, L.(2014). Communicating hurricane evacuation to tourists: Gender, past experience with hurricanes, and place of residence. Journal of Travel Research. 54. 3. 329–343

Chen, I.S.(2011). Oral History of Typhoon Morakot: 2009-2010’s Interview Records. Taipei: Chen-wei Publishing.

Cyprien, G.(2021). Local response strategies: the case of 2016’s Hurricane Mathew in Bony Chardonnières of Haiti. Master thesis. Taiwan: National Cheng Kung University.

Dixit, V.V., Wilmot, C., Wolshon, B.(2012). Modeling risk attitudes in evacuation departure choices. Transportation Research Record. 2312. 159–163.

Dlamini, S.(2020). Disaster Management system of Swaziland-the 2016 Drought. Master thesis. Taiwan: National Cheng Kung University.

Doyle, J.(2017). Hurricane Harvey. Minnesota: Abdo Publishing.

Drabek, T.E.(2007). Community Processes: Coordination. In Handbook of Disaster Research edited by Rodríguez, H., Quarantelli, E.L., and Dynes, R.R. 217-233. NY: Springer.

Fu, H., Wilmot, C.G., Zhang, H., Baker, E.J.(2007). Modeling the hurricane evacuation response curve. Transportation Research Record. 2022. 94–102.

Herzberg, F.(1968). One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees? Harvard Business Review. 46, 53-62.

Keeling, A.W., and Wall, B.M.(2015). Nurses and Disasters: Global, Historical Case Studies. Editors. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

Kiefer, J.J, and Montjoy, R.S. (2006). Incrementalism before the Storm: Network Performance for the Evacuation of New Orleans. Public Administration Review. Special Issue. 122–130.

Kuligowski, E.D., and Gwynne, S.M.V.(2009). The need for behavioral theory in evacuation modeling. Pedestrian and evacuation dynamics. https://tsapps.nist.gov/publication/get_pdf.cfm?pub_id=861543, last accessed 23 January 2024.

Kuligowski, E.D., and Peacock, R.D.(2005). A Review of Building Evacuation Models. National Institute Of Standards And Technology. U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON.

Maslow, A.H.(1954). Motivation and Personality. New York: Harper & Row.

McEntire, D.A.(2007). Local Emergency Management Organizations. In Handbook of Disaster Research edited by Rodríguez, H., Quarantelli, E.L., and Dynes, R.R. 168-182. NY: Springer.

Morss, R.E., Demuth, J.L., Lazo, J.K., Dickinson, K., Lazrus, H., and Morrow, B.H.(2016). Understanding public hurricane evacuation decisions and responses to forecast and warning messages. Weather and Forecasting. 31. 2. 395–417.

Munkhtuya, D.(2018). Research on the Effectiveness of 2016’s Dzud Disaster Responses in Zavkhan Province, Mongolia. Master thesis. Taiwan: National Cheng Kung University.

Nambisan, S.(2009). Platforms for collaboration. Stanford Social Innovation Review. 7:44–9.

Neyzsa, A.(2023). Research on the Effectiveness of Imanuel Mainang Church Disaster Response in the Case of 2021’s Seroja Tropical Cyclone in Indonesia. Master thesis. Taiwan: National Cheng Kung University.

Ndayirata, A.(2024). Research on Mozambique’s Disaster Management System – the Response to 2019’s Cyclone Idai. Master thesis. Taiwan: National Cheng Kung University.

North, D. (1990). Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Paul, B.K.(2012). Factors affecting evacuation behavior: The case of 2007 Cyclone Sidr, Bangladesh. Professional Geographer. 64. 3. 401–414.

Perry, R.(1979). Evacuation Decision-Making in Natural Disasters. Mass Emergencies. 4. 25-38.

Pongen, Yimchungrenla(2022). Disaster management system: The case of the 2016 Meinong Earthquake at Kunshan community of Tainan City. Tainan City: Master thesis at National Chen Kung University.

Preston, J., and Kolokitha, M.(2015). City Evacuations: Their Pedagogy and the Need for an Inter-disciplinary Approach. In City Evacuations: An Interdisciplinary Approach. edited by J. Preston, J.M. Binner, L. Branicki, T. Galla, N. Jones, J. King, M. Kolokitha, and M. Smyrnakis. 1-20. Heidelberg: Springer.

Quarantelti, E.L.(1980). Evacuation Behavior And Problems: Findings And Implications From The Research Literature. The Ohio State University: Department of Sociology, Disaster Research Center.

Robertson, P. J. (1996). Interorganizational relationships: Key issues for integrated services. Working Paper. Los Angles, CA.: University of Southern California.

Rodr´ıguez, H., D´ıaz, W., Santos, J.M, and Aguirre, B. E.(2007). Communicating Risk and Uncertainty: Science, Technology, and Disasters at the Crossroads. In Handbook of Disaster Research edited by Rodríguez, H., Quarantelli, E.L., and Dynes, R.R. 476-488. NY: Springer.

Rodríguez, H., Quarantelli, E.L., and Dynes, R.R.(2007). Handbook of Disaster Research. Editors. NY: Springer.

Salancik, G.R., & Pfeffer, J.(1978). A Social Information Processing Approach to Job Attitudes and Task Design. Administrative Science Quarterly. 23. 224-252.

Salancik, G.R., & Pfeffer, J.(1977). An Examination of Need-Satisfaction Models of Job Attitudes. Administrative Science Quarterly. 22. 427-456.