12 Migrant Displacement in Conflicts: Emergency Management Response to Ukrainian Refugees and Turkish Asylum Seekers in Germany

Cihan Aydiner, Ph.D.; Iuliia Hoban , Ph.D.; Tanya Buhler Corbin, Ph.D.; and Logan Gerber-Chavez, Ph.D.

Authors

Cihan Aydiner, Assistant Professor of Homeland Security and Associate Department Chair, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Worldwide

Iuliia Hoban, Assistant Professor of Human Security & Resilience and Program Chair, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Worldwide

Tanya Buhler Corbin, Professor of Disaster Management and Department Chair, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Worldwide

Logan Gerber-Chavez, Assistant Professor of Disaster Studies, Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Worldwide

Keywords

displacement; migrants; refugees; asylum seekers; humanitarian crises; disasters; transboundary crises; Germany; Türkiye; Ukraine; European Union

Abstract

The global crisis of displacement, prominently illustrated by Ukrainian refugees and Turkish asylum seekers in Germany, presents a multifaceted challenge that demands proficient emergency management and adept policy intervention. Ukrainian refugees have sought safety from the 2022 Russian invasion, while Turkish asylum seekers, fleeing from the government’s crackdown on opposition groups in the aftermath of the 2016 coup attempt in Türkiye, differ from Germany’s earlier Turkish migrants by often being highly educated and previously holding significant prominence in society. With an influx of Ukrainian and Turkish populations into Germany, the diaspora introduces unique challenges. Analyzing the plight and integration of these groups into German society offers critical insights for disaster management professionals. It elucidates the complexities of aiding refugees and asylum seekers, emphasizing the importance of tailored public policies and humanitarian efforts. This chapter aids in addressing immediate needs and understanding the broader implications of forced migration. For disaster management stakeholders, this scenario enhances global cultural competency and humility, and simultaneously refines strategies for managing crises stemming from conflict or political unrest, thereby strengthening the overall effectiveness of international disaster response mechanisms.

Introduction and Problem Statement

The displacement of individuals due to conflict, persecution, and oppression is a pressing global issue. Germany stands as a prime example of hosting two significant groups recently affected by crises: Ukrainian refugees fleeing the 2022 Russian invasion and Turkish asylum seekers escaping the government’s post-2016 coup crackdown. Unlike traditional Turkish migrants to Germany, these asylum seekers are often highly educated and previously held significant roles, marking a new phase in the Turkish diaspora with distinct challenges for emergency management. This study examines Germany’s strategies for addressing the needs of these groups, providing insights into disaster management, integration policies, and their implications for international humanitarian efforts. It highlights the emergency management response to these new waves of displaced people. This study focuses specifically on Ukrainian and Turkish migrants. Ukrainian refugees have been granted temporary protection in the EU, including Germany, under specific directives that recognize the urgent need for refuge from the conflict in Ukraine. In contrast, Turkish asylum seekers are applying for international protection in Germany due to fears of persecution following the 2016 coup attempt, with their status and rights being determined through the asylum process. By analyzing the integration and support provided to these groups, this case study highlights the nuanced challenges and opportunities presented by their displacement, underscoring the importance of tailored public policies and humanitarian efforts to address their immediate needs and facilitate long-term integration.

The German emergency management structure is similar to the United States’ system, with shared responsibilities between the federal and state levels. This institutional structure establishes the organization of emergency management for disaster management and permits delegation duties to the local and regional levels; the federal government is in charge in war or armed conflict. For humanitarian aid and international disaster relief efforts, the federation coordinates efforts with partners, including neighboring states (European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations, 2021).

Over the last two decades, Germany’s immigration policies, particularly concerning refugees and asylum seekers, have undergone significant transformations. Before the year 2000, migrant integration measures were primarily managed by local governments, civil society organizations, and employers. During the early 2000s, German immigration policies began shifting from a primary focus on preventing immigration to recognizing the potential benefits of immigration, especially from highly skilled individuals. The “Immigration Law” of 2004 was a significant overhaul of existing laws about foreign nationals and asylum requirements. It aligned immigration regulations with economic and labor market interests and included provisions for integrating immigrants into German society. From 2000 to 2004, the Green Card Initiative facilitated the temporary immigration of IT specialists. Later, in 2012, the Blue Card program was introduced for highly qualified third-country nationals, lowering income requirements for certain shortage professions like IT and medicine. Employment regulations were also amended to open the labor market for certain specialists from third countries. The Federal Employment Agency identified professions needing specialists who could be recruited from abroad. There was a gradual reduction of barriers for asylum seekers with a likelihood of remaining in Germany, aiming to facilitate their social integration (Hanewinkel & Oltmer, 2018).

Germany’s response to the 2015 refugee crisis was notable in its recent migration history. Chancellor Angela Merkel’s decision to allow a record number of 1.1 million asylum-seekers, primarily from Syria, to enter Germany was controversial. Germany refined asylum policies, focusing on integration, and reducing the number of asylum-seekers through agreements with other EU countries and strengthening their border security. The COVID-19 pandemic brought a decline in immigration and asylum applications. This reduction continued a trend that had started in 2016, after the peak of the refugee crisis. These developments reflect a gradual but significant shift in Germany’s approach to immigration and asylum, balancing humanitarian concerns with economic and labor market considerations. Policies have evolved to view migration as a challenge and an opportunity, particularly because of the growing need for skilled labor (Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, 2022; Hanewinkel & Oltmer, 2018). These policy developments reflect Germany’s evolving approach to migration, emphasizing integration, social cohesion, and the need for skilled foreign labor. The changes aim to create a more comprehensive and long-term policy framework that balances the benefits of migration with the challenges it presents (Aydın, 2016).

Recent developments have necessitated further adaptations in Germany’s immigration and asylum policies. In response to the Ukraine crisis and the influx of highly skilled Turkish asylum seekers, Germany has updated its temporary protection measures and professional qualification recognition processes. These adjustments reflect a commitment to aligning migration policies more closely with current humanitarian needs and economic priorities. However, increasing numbers of immigrants might challenge these efforts in the future, potentially straining resources and complicating the balance between welcoming newcomers and ensuring sustainable integration. This tension underscores the need for Germany to remain adaptive and proactive in policy responses in a rapidly changing global context.

The Ukrainian Population in Germany

Since the beginning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Germany has received 1.2 million refugees displaced by the war (Council of the EU, 2023; United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), n.d.). Policies governing the reception of Ukrainian refugees in Germany differ significantly from other refugee groups (Brücker, Ette, Grabka, Kosyakova, Niehues, Rother, Spieß, Zinn, Bujard, Cardozo Silva, et al., 2023). The activation of the “Temporary Protection Directive” (2001/55/EC) bypassed the traditional asylum procedure and issued temporary residence permits until March 2024, expediting access to employment and integration opportunities (Brücker, Ette, Grabka, Kosyakova, Niehues, Rother, Spieß, Zinn, Bujard, Cardozo Silva, et al., 2023). In contrast to other asylum seekers, who usually must undergo waiting periods and labor market tests, Ukrainian refugees were given immediate access to the labor market (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2023). The significance of this policy cannot be overstated as it quickly provided Ukrainian refugees with “legal security as well as certainty for future planning” (Brücker, Ette, Grabka, Kosyakova, Niehues, Rother, Spieß, Zinn, Bujard, Cardozo, et al., 2023, p. 7). Ukrainians are not obligated to stay in reception facilities designated for refugees. Furthermore, starting in June 2022, Ukrainian refugees became eligible for basic social benefits, medical care, accommodation, and access to the education and labor market under the federal German Code of Social Law II rather than the Asylum Seekers Benefits Act. This protection is initially valid for one year and can be extended up to three years (CEDEFOP, 2022). This change results in higher benefit rates and integration into the support structure of German job centers, including access to language classes (Brücker, Ette, Grabka, Kosyakova, Niehues, Rother, Spieß, Zinn, Bujard, Cardozo, et al., 2023).

Ukrainian refugees in Germany are highly educated, with 72 % holding a tertiary degree (Reuters, 2022a). This educational profile contributes to the enrichment of the host country’s human capital and holds promise for the refugees’ successful integration into the German workforce. Language acquisition remains one of the main challenges for refugees’ integration, with only 4 % of Ukrainian refugees reporting a good command of the German language (Brücker, Ette, Grabka, Kosyakova, Niehues, Rother, Spieß, Zinn, Bujard, Cardozo, et al., 2023). At the same time, surveys demonstrate that, from 2022 to 2023, the share of Ukrainian refugees who are enrolled in German language courses increased from 50 to 65%, with 10% completing the training (Brücker, Ette, Grabka, Kosyakova, Niehues, Rother, Spieß, Zinn, Bujard, Cardozo, et al., 2023; Brücker, Ette, Grabka, Kosyakova, Niehues, Rother, Spieß, Zinn, Bujard, Cardozo Silva, et al., 2023; European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights., 2023). Survey data also suggests that language remains the main barrier to entering the workforce (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights., 2023).

Across Germany and other European countries, most Ukrainian refugees are women (80%) due to the requirements for military service for males. Seventy-seven percent fled to Germany without a partner, and 48 % with minor children (Brücker, Ette, Grabka, Kosyakova, Niehues, Rother, Spieß, Zinn, Bujard, Cardozo, et al., 2023). This differs from other refugee flows, where women accounted for about 30% of all asylum applications during Europe’s 2015-17 refugee crisis (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2023). Like other OECD countries, Germany supported the development of initiatives to empower Ukrainian migrant and refugee women to address their challenges and foster their inclusion in the workforce and society. The MY TURN program is notable for its gender-sensitive and lifestyle-oriented approach. It provides specialized advice and individual support to help immigrant women, including those with migrant parents, gain qualifications, training, and employment with social security contributions (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2023).

Germany’s approach to Ukrainian refugees demonstrates a robust and humane response, characterized by immediate protection, financial assistance, and efforts to facilitate integration into German society. The German governmental support for displaced Ukrainians included complimentary transportation and health coverage, social housing or subsidized rental options, monthly financial support amounting to approximately 450 euros, and supplementary payments for each dependent child (Andrews et al., 2023; Richtmann, 2022). Despite the support, most Ukrainian refugees, while grateful for the support, intend to return to Ukraine once it is safe. As of 2023, 37% of Ukrainians indicated they want to settle in Germany permanently and 15% for an extended period (Brücker, Ette, Grabka, Kosyakova, Niehues, Rother, Spieß, Zinn, Bujard, Cardozo Silva, et al., 2023; Reuters, 2022b; Weitz, 2022).

The Turkish Population in Germany

The Turkish population in Germany has a long history, with significant migration phases that have shaped their presence there. The first wave occurred in the 1960s, driven by labor needs in Germany. These early migrants were mostly semi-skilled or unskilled workers. The 1980s saw a shift, with migration increasingly motivated by political factors, including a military coup and the Kurdish conflict. This wave included more skilled and educated individuals. With the 2016 coup attempt, the migration pattern shifted dramatically, consisting predominantly of highly educated professionals fleeing due to political oppression and economic instability. The migration of these individuals was characterized by a sense of urgency and necessity, contrasting with earlier economic-driven migrations. The integration and management of these educated migrants posed new challenges for German authorities, as these individuals often had higher qualifications and different integration needs than previous Turkish migrants (Aydiner & Rider, 2022; Fassmann & İçduygu, 2013). In 2023, almost 1.5 million people with Turkish citizenship were residing in Germany (German Federal Statistical Office, 2022). However, this number does not account for people of Turkish descent who may have acquired German citizenship (for example via asylum or refugee status) or are citizens of other countries; approximately 3 million individuals with Turkish roots are estimated to reside in Germany (Associated Press, 2024). The migration corridor between Germany and Türkiye has a complex history, marked by diverse economic, social, and political factors influencing migration movements between the two countries. The migration of Turkish nationals to Germany includes highly skilled Turks moving to Germany for employment and German citizens retiring in Türkiye.

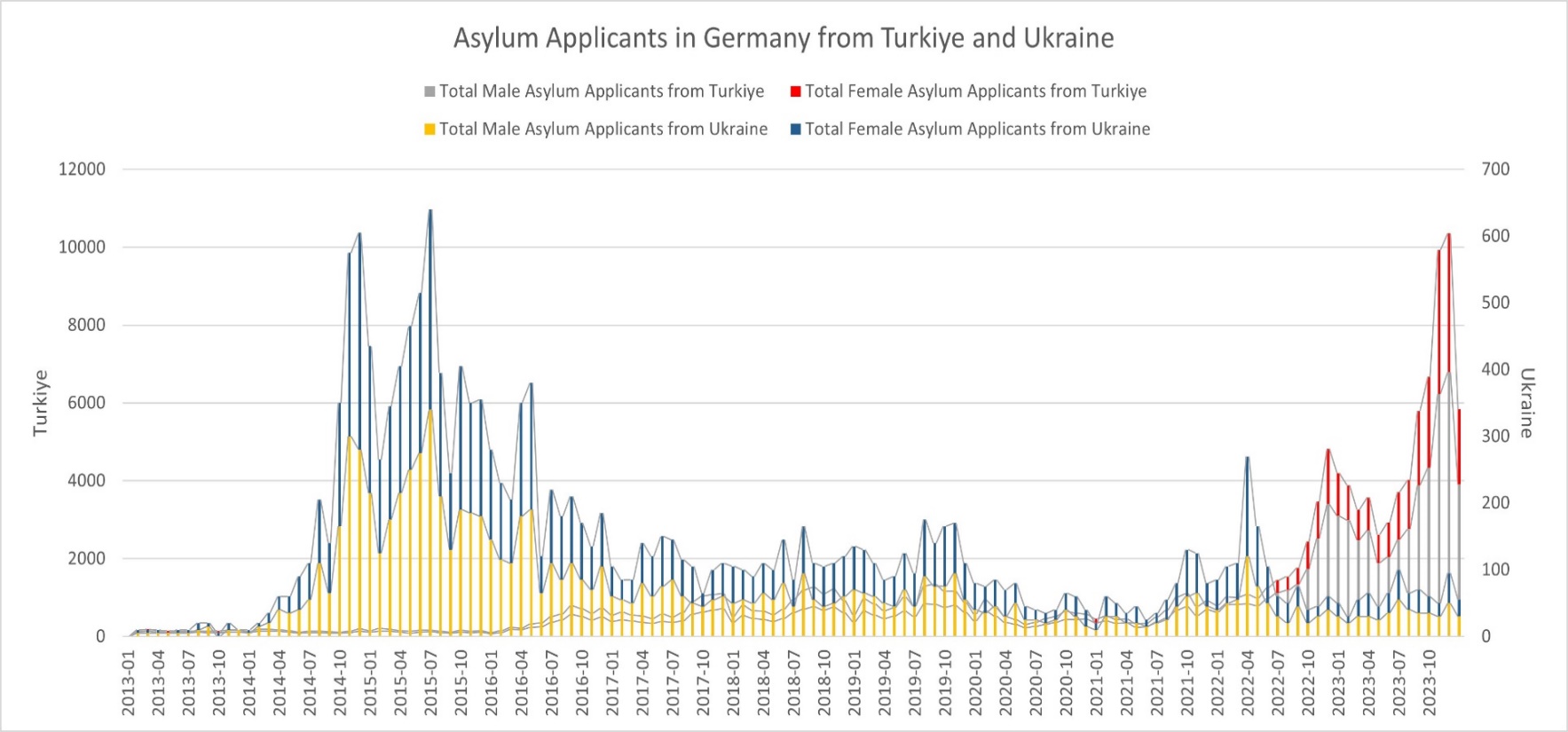

Turkish citizens seeking asylum in Germany significantly increased following the failed coup attempt in Türkiye in July 2016 from an average of nearly 1,800 per year to 5,742 in 2016. This trend continued in the subsequent years, with 8,483 applications in 2017, and 10,655 in 2018. By 2019, the number had reached 11,423 (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), n.d.). The increase in asylum applications is attributable to the political and social aftermath of the coup attempt, including the crackdown on opposition figures and the deteriorating economic situation in Türkiye. In 2020, despite a global drop in asylum applications due to the pandemic, Turkish citizens ranked as the fourth largest group seeking asylum in Germany with 5,196 applications (Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, 2022). In 2021, 7,067 Turkish citizens applied for asylum in Germany; the following year, this number more than tripled to 23,938. The escalation in applications in these years can be linked to ongoing political and economic challenges in Türkiye, including issues related to human rights and freedom of expression (Topcu, 2023).

This historical context is crucial for understanding the varied experiences of Turkish migrants in Germany and their integration into German society. The contrast between the early labor-driven migration and the recent politically driven exodus underscores the diverse causes and experiences of migrants and the complexities of humanitarian efforts and public policy in forced migration scenarios. Turkish people seeking refuge in Germany after the 2016 coup attempt have a different profile compared to the Ukrainian refugees. This group comprises various professionals, including educators, journalists, scholars, business professionals, and members of the judiciary, who fled to avoid persecution or job loss. Their forced migration, often due to political reasons, marks a significant shift from earlier Turkish migration patterns primarily driven by economic factors or labor needs. Unlike the Ukrainians, who benefited from visa-free entry and the “Temporary Protection Directive,” Turkish asylum seekers in Germany face more stringent asylum processes and a lower likelihood of obtaining asylum status. The changing economic and political landscape in Türkiye, characterized by increased oppression and economic instability, has been a driving factor in this migration. The German government has faced challenges balancing its diplomatic relations with Türkiye while addressing the surge in asylum applications. This situation has required careful navigation of international law, human rights obligations, and national security concerns.

In the next section, we situate our argument within the existing scholarship that examines the relationship between displacement, conflict, and disasters and discourse on vulnerability and resiliency among displaced populations. We identify the need for a comparative study of diverse displaced groups’ resettlement and integration experiences, particularly in the German context. The subsequent sections offer a detailed analysis of the policy landscape, data collection, and use of thematic analysis to identify key patterns pertinent to the protection and integration of Ukrainian and Turkish refugees in Germany. Through comparative analysis, we examine divergent trajectories and outcomes of resettlement and integration of Ukrainian and Turkish displaced populations. We conclude with a discussion of implications of the findings and offer recommendations for designing policies for the resettlement and integration of displaced populations. The chapter emphasizes the importance of inclusive, rights-based policies that foster full participation and empowerment of displaced populations.

Literature Review

Displacement, Conflict, and Disasters

The world is facing unprecedented transboundary challenges, chief among them the global humanitarian crisis of 114 million people displaced by conflict and disasters (UN News, 2023). Displaced populations face a myriad of challenges ranging from integration issues—including obtaining visas and asylum—to the absence of fundamental humanitarian needs. Moreover, they may be marginalized within host countries, potentially leading to internal conflict (Bohnet et al., 2021; Migration Data Portal, 2023). This situation is particularly precarious when the displaced population is also grappling with ongoing issues such as climate change or limitations in state capacity, which could further exacerbate conflict if there is a lack of proper planning and infrastructure allocated to support displaced populations (Bohnet et al., 2021). Additional concerns host country residents have about displaced populations include fears of the risks of radicalization and the spread of infectious diseases due to inadequate healthcare, as well as internal job losses and declining wages as countries strive to meet employment demands (Dadush & Niebuhr, 2016; Hossain et al., 2023). Additionally, from research on displacement after disasters, we have learned that migrant populations require systematic and sustained resources and support in recovery operations, presenting unique challenges for the host locations (Corbin, 2021; Esnard & Sapat, 2014).

Prior research on displaced migrants focuses on the overarching European refugee and migrant crisis, with Syrian migrants being a central focal point (Menéndez, 2016; Quinn, 2016; Sirkeci, 2017; Stockemer et al., 2020). While some attention is paid to Ukrainian and Turkish displaced populations, there remains a gap in a comparative study of their experiences, especially in the German context (Aydiner & Rider, 2022; Lloyd & Sirkeci, 2022; Thijssen et al., 2021). Most studies explore the socio-economic integration of these groups after displacement, yet there is limited exploration of their initial experiences, interactions with German officials, and German migration policies (Duszczyk et al., 2023; Fasani et al., 2022; Feinstein et al., 2022; Gurer, 2019). Furthermore, comprehensive studies examining preparedness and response from host countries like Germany, considering these specific forced migrations, are scarce. Emergency management research about displaced peoples in Germany is limited to healthcare availability and health standards in refugee support facilities (Kozman et al., 2024). The structured integration process for asylee applicants in Germany, particularly for highly educated Turkish asylum seekers, underscores the nuanced challenges and opportunities presented by their displacement, necessitating tailored public policies and humanitarian efforts to address their immediate needs and facilitate long-term integration (Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, 2023b).

While disaster scholars recognize the crucial role that human security plays in establishing resilience to and recovery from disasters, there is a gap in our knowledge about migrant displacement after conflicts and the effects on human security. Recent disaster vulnerability research has begun to address this gap, examining vulnerability, conflict, and state relations in society (Artur, 2022; Hilhorst, 2022; Jaspars, 2022; Siddiqi, 2022). Of particular importance for this study is the relationship between conflict and disaster, where conflict can increase or worsen hazards (e.g., increasing vulnerabilities through displacement) (Hilhorst, 2022).

Vulnerability and Displacement

The term refugee, in contrast to other groups of migrants has “more political, legal, and social meanings” (Xie & Chao, 2022, p. 106). The United Nations Refugee Convention provides a critical distinction for groups of people who are displaced by war and persecution. While offering needed protection, the resettlement and acculturation process can be particularly challenging as refugees face economic instability, marginalization, and alienation, hence creating structural barriers to their (re)integration and economic mobility in a host state.

The research on vulnerability in the context of disasters notes that factors such as social class, education, and language proficiency often play a more significant role in determining vulnerability than the nature of the disaster itself (Donner & Rodríguez, 2008; Gaillard, 2010; Kelman et al., 2016). Some scholars argue that minority communities, such as those from refugee backgrounds, often exhibit lower preparedness levels for disasters, possess limited resources for evacuation, and face disparities in accessing aid and recovery assistance (Donner & Rodríguez, 2008; Koike, 2011). The cultural and linguistic diversity within refugee communities adds additional complexities that must be considered for effective disaster response (Hanson-Easey Scott et al., 2015; Spittles & Fozdar, 2008). Specifically, cultural beliefs and attitudes play a crucial role in shaping these communities’ perceptions of potential hazards, influencing their disaster preparedness, and determining their responsiveness to government warnings (Marlowe & Bogen, 2015).

Recent scholarship argues that the focus on vulnerability should shift from labels to layers (Luna, 2009; Marlowe et al., 2018). This involves acknowledging potential vulnerabilities while also recognizing the capabilities of communities to mitigate and eliminate layers of vulnerability. From this perspective, refugees can be simultaneously socially vulnerable and more resilient due to their experiences with displacement and resettlement (Alachkar, 2023; Uekusa, 2019; Xie & Chao, 2022). Refugees are typically at a higher risk compared to other groups in the host countries due to their diverse backgrounds and past experiences. At the same time, scholars show that this vulnerable population has demonstrated impressive recovery, adaptability, and resilience in the face of disasters (Uekusa & Matthewman, 2017; Xie & Chao, 2022). Coping mechanisms adopted by individuals and communities in response to disasters in their home countries offer a wealth of practical knowledge (Uekusa & Matthewman, 2017). Analyzing these strategies at an individual and collective level can provide valuable insights for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers in developing more effective responses to disasters.

The research on refugees’ resilience identifies factors that protect and promote resilience (Alachkar, 2023; Ciaramella et al., 2022; Kashyap, 2014) and how refugees develop skills and competence in dealing with a threat or risk. The coping mechanisms that foster refugees’ resilience include support of family and community support, religious or spiritual beliefs, attitudes, and the attribute to their experience (Alachkar, 2023). National cultures influence protective action behavior. For example, for places like the US, which places strong emphasis on individualism, the protective behavior is influenced by self-efficacy and perceived security, whereas places like Korea value community social norms for preparedness instead of individual characteristics (Cho & Lee, 2015).

Building on the understanding of refugees’ resilience and coping mechanisms, it is crucial to consider how legal frameworks and national policies also play a decisive role in shaping the integration and long-term stability of displaced populations. Incorporating elements from the German Nationality Act and the experiences of Turkish asylum seekers post-2016, it is evident that legal frameworks and national policies significantly impact the integration and status of displaced populations. The changes to Germany’s citizenship laws in 2024 to shorten residency requirements for naturalization reflect a progressive approach to integration, potentially benefiting displaced populations, including Turkish asylum seekers affected by post-coup purges in Türkiye. These legislative adjustments and the documented increase in asylum applications from Turkish citizens post-2016 underscore the complex interplay between national policies, global conflicts, and individual displacement experiences, further highlighting the need for nuanced approaches to asylum and integration policies within host countries (Schuetze, 2024; Stockholm Center for Freedom, 2022). The integration of asylee applicants in Germany, particularly those from Türkiye following the coup attempt, involves a comprehensive process from application to potential naturalization. This process reflects the complexities of navigating asylum and integration in a host country, emphasizing the need for policies that are responsive to the diverse backgrounds and needs of displaced individuals (Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, 2023b; Schuetze, 2024). This exploration underscores the critical need to study how legal policies, coupled with an understanding of refugee resilience and vulnerabilities, influence the integration and welfare of displaced populations, particularly focusing on the adaptive legal responses seen in Germany’s approach to Turkish asylum seekers, Ukrainian refugees, and other vulnerable groups.

Data and Methodology

For the analysis in this chapter, we collected policy documents from distinct levels of government. From the European Union, we retrieved documents directly from EU-Lex. This database is recognized as the official and most exhaustive repository of EU legal documents. At the national level, we sourced federal policy documents across German federal agencies including the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) and the Federal Ministry of the Interior and Community (BMI). Additionally, we incorporated open-source data to locate policy information pertinent to our research questions, emphasizing identifying relevant policy documents at the local level. We also used open-source data to identify relevant policy data related to our research questions, with a specific focus on the policy documents on the local level. We identified twelve policy documents at the EU level, nine at the federal level, and two at the local level. Furthermore, our analysis benefitted from leveraging published surveys and reports conducted by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, BAMF, and United Nations agencies. Asylum applications numbers were compiled from the World Bank World Development Indicators via the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees for every month from 2015-2023 (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees n.d.).

While our data collection process aimed to be comprehensive, we acknowledge certain limitations in our approach. The identified policy documents at the EU, federal, and local levels may not fully represent the entire policy landscape. Specifically, certain documents, particularly those at the local level, may not be accessible through open-source data, potentially leading to gaps in our coverage of the policy landscape. Despite our emphasis on local-level policy documents, the limited availability of such materials limits our analysis. We addressed this limitation with the incorporation of open-source data such as reports and surveys that had a specific focus on the local level to supplement the primary documents. To ensure the reliability of open-source data, we conducted quality checks and cross-referencing to enhance the accuracy of our analysis.

We analyzed the documents using deductive means to create initial thematic categories. We conducted a content analysis derived from a comprehensive compilation of policy documents related to the refugee policy in the European Union in general and Germany specifically. Content data analysis is particularly valuable for analyzing qualitative data systematically and identifying patterns within a dataset, highlighting the adaptability of this method adaptability for extracting meaningful insights from qualitative data across diverse research contexts (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Mayring, 2000, 2019; Morgan, 1993; Riger & Sigurvinsdottir, 2016, p. 33). Thematic analysis may be done inductively or deductively (Riger & Sigurvinsdottir, 2016). Although our approach is deductive and informed by existing literature, we also allowed the policy document data to guide the selection of themes. Scholars identify six stages of thematic analysis that we follow in our study: 1). Familiarization with the data,2). Generating initial codes, 3). Searching for themes, 4). Reviewing themes, 5). Defining and naming themes, 6). Writing the report (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Riger & Sigurvinsdottir, 2016).

The researchers conducted a content analysis by reading and identifying themes in the policy documents. The thematic analysis focused on identifying and consolidating themes related to asylum seekers’ protection and refugee protection. The research team regularly engaged in collaborative discussions throughout the iterative process of searching for, reviewing, defining, and naming themes. In the final stage, we synthesized our findings and presented a comprehensive analysis in the next discussion section.

Findings and Solutions

Informed by the literature, the content analysis of policy documents revealed two main themes across the data: (1) protection for refugees as it pertains to Ukrainian population dispaced by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and, (2) asylum seekers protection as it pertains to the Turkish displaced population in Germany.

Theme 1

The influx of displaced Ukrainians into the European Union because of the Russian invasion of Ukraine has brought attention to the Temporary Protection Status, an important international policy to safeguard refugees (Karaçay, 2023). Governments apply for temporary protection as a pragmatic tool to address large-scale displacement, allowing them to sidestep their responsibilities within the international refugee framework. This approach often discourages local integration, restricts protection, and facilitates repatriation (Ilcan et al., 2018). Temporary protection has emerged as a critical component in the European Union’s response to humanitarian crises, including in the context of wars following the collapse of Yugoslavia and Russia’s war on Ukraine (Hageboutros, 2016). For example, in Germany, Bosnian refugees had very restricted entry to the German labor market, and there were a very limited number of integration measures to assist them (Barslund et al., 2017; Bastaki, 2018). Carrera and Ineli-Ciger argue that the approach to implementation of temporary protection directives illustrates “systemic unequal solidarity” among EU member states (2023, p. 4).

To develop the EU-wide model of temporary protection, the European Union established the Temporary Protection Directive (TPD) in 2001 in reaction to the forced displacement that occurred after the Bosnia (1992-1995) and Kosovo (1998-99) wars. However, the EU institutions have never put this directive into practice or activated it until Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 (Carrera & Ineli Cigar, 2023; Heidbreder, 2024; Xhardez & Soennecken, 2023). TPD provides wide-ranging protections to those displaced by conflict, granting access to the labor market, residence permits, and essential services. Furthermore, following the adoption of TPD, the European Council approved measures totaling approximately €17 billion to support Ukrainian refugees by activating cohesion funds (Heidbreder, 2024). Notably, the document stipulates that TPD can be invoked in cases labeled as a “mass influx” of displaced people from third countries. However, the document is ambiguous about conditions on what qualifies as mass influx, leading to arbitrary use (Carrera & Ineli Cigar, 2023).

The approach used to address immigrants varied in diverse ways (Barslund et al., 2017). For Bosnian refugees, the residence permit was granted only initially.In the Syrian case, displaced population residents received only a temporary permit. Meanwhile, Ukrainians were granted permits for the duration of their stay Notably, temporary protection serves as a short-term response to accepting refugees in the host countries. While it offers temporary shelter, necessities, and safety, it is not a long-term solution for their integration into the host country. The question remains whether the EU will continue extending TPD or whether opportunities to stay will be provided by member states. There is a possibility that governments in slowing economies may struggle to offer refugees jobs, housing, and services, potentially leading to a decrease in solidarity and a backlash, which Europe has witnessed in the past. While humanitarian aid rooted in the local community’s willingness to assist refugees is crucial in emergency situations, it may become problematic as economic, social, and political costs increase if the “emergency” persists over an extended or indefinite period (Bőgel et al., 2023).

Germany passed provisions to implement TPD through Section 24 of the Residence Act, which also allowed the issuing of temporary residence permits for Ukrainians who fled following the Russian invasion (Brücker, Ette, Grabka, Kosyakova, Niehues, Rother, Spieß, Zinn, Bujard, Cardozo, et al., 2023). Ukrainian refugees could access fundamental social benefits through the Code of Social Law II (Sozialgesetzbuch II) rather than the Asylum Seekers Benefits Act (Asylbewerberleistungsgesetz). These legal conditions, initially valid until March 2024 but then extended, as of writing until March 2025, allowed Ukrainian refugees to receive both work permits, and residence permits. These conditions facilitated the integration of Ukrainians into the German labor market (Brücker, Ette, Grabka, Kosyakova, Niehues, Rother, Spieß, Zinn, Bujard, Décieux, et al., 2023).

Ukrainians were integrated into the support system of German job centers, including participation in language classes. The latter is central to refugees’ integration into the labor market. For example, the fall 2022 survey indicated that 51 % were either enrolled in German classes or had successfully completed at least one course. By the beginning of 2023, this figure increased to 65 % of actively participating refugees. Importantly, the prevalence of integration courses (Integrationskurs), constituting 87 % of participants, underscores the significance of these programs (Brücker, Ette, Grabka, Kosyakova, Niehues, Rother, Spieß, Zinn, Bujard, Décieux, et al., 2023). The quick integration of displaced Ukrainians into the German workforce demonstrates that refugees can secure employment promptly, given appropriate circumstances. This progress can be partly credited to the relatively high levels of education among displaced Ukrainians and, in certain instances, their connections to the local diaspora (Desiderio & Hooper, 2022).

The temporary protection status also increased financial benefits. Ukrainian refugees in Germany received a 15% rise in the financial assistance amount compared to what asylum-seekers might qualify for under the Asylum Seekers Benefits Act. Previously, the handling of new arrivals fell under the authority of social agencies in accordance with Asylum Law. Now, either the job centers, responsible for assisting those capable of employment, or the social agencies of municipalities, overseeing all other cases, administer support in accordance with German Social Law (Hegedüs et al., 2023).

Another significant distinction in the accommodation of Ukrainian refugees is in housing support. Most lived in private accommodations, with only 9% staying in publicly provided group housing for refugees (Haase et al., 2024; Hegedüs et al., 2023). In contrast, asylum seekers are typically housed in various types of reception centers, which became the centerpiece of German asylum policy following the increase in refugee migration in 2014-2015 following the Syrian civil war (Göler, 2020).

Further, given that most arrivals from Ukraine are women with children, the provision of adequate childcare becomes central to refugees’ social integration (Dhingra & Roehse, 2023; Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2023). Access to daycare was limited, and experts recommended expanding childcare options to facilitate mothers in enrolling in language courses and seeking employment (Brücker, Ette, Grabka, Kosyakova, Niehues, Rother, Spieß, Zinn, Bujard, Décieux, et al., 2023). In addition, while all recently displaced persons have vulnerabilities, the atypical gender profile of Ukrainian refugees (between 70 and 90 % being women) exposes them to the risk of gender-based violence and different forms of exploitation including human trafficking (Cimino & Degani, 2023; Freedman, 2016; Phillimore et al., 2023). The arrival of refugees after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine raises a set of questions about the EU’s future policy concerning humanitarian crises. It prompts reflection on the implementation of more equitable refugee regulations that guarantee a non-discriminatory approach to welcoming displaced populations.

Theme 2

The integration and protection of Turkish asylum seekers in Germany, particularly following the 2016 coup attempt in Türkiye, has unfolded along a structured yet nuanced pathway designed to facilitate their smooth transition into German society. This process, aimed at ensuring the necessary support for their integration, spans various aspects of an individual’s life, from legal status regularization to social integration, paying special attention to the unique challenges faced by highly educated Turkish applicants. These challenges include the recognition of their professional qualifications and the intricacies of navigating the asylum application process (Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, 2023b).

The journey toward asylum and integration into the German job market is characterized by significant administrative variability and challenges, including long waiting times for asylum decisions and difficulties in recognizing professional qualifications. This has led to uncertainty and stress among applicants, highlighting the need for policy adaptations and advocacy to effectively navigate these challenges. Despite the uniformity of procedures across different national origins, Turkish asylum seekers have presented German authorities with unprecedented challenges. High-status individuals, often arriving with diplomatic visas and proficient in English, have distinguished themselves with their swift asylum approval rates, reflecting their professional backgrounds and the authorities’ recognition of their unlikely involvement in the coup attempt. In the initial wave of applications from 2016 to 2019, the asylum grant rate for these applicants reached 47.4% in 2019 (Duvar English, 2020). However, these high-status individuals faced stark changes in their transitions into life within refugee camps, experiencing psychologically traumatic conditions starkly contrasting with their previous roles and residences. This experience in particular points to a need for better integration of lessons on cultural competence and sheltering procedures that are utilized in emergency management (Knox & Haupt, 2020). This situation has also underscored a narrative of differential treatment within the asylum system, notably when compared to the more favorable support perceived to be received by Ukrainian refugees from both German authorities and the public.

In the years following the coup attempt, the demographics of Turkish asylum applicants broadened significantly, with a notable increase in applications from individuals of Kurdish origin. Despite the surge in application numbers, the acceptance rate for this group was significantly lower, dropping to 13%, indicative of the perceived weaker grounds for asylum compared to their predecessors. This shift in the acceptance rate, despite exceeding 60,000 applications, reflects the evolving dynamics of Turkish asylum seekers in Germany and underscores the complexities of navigating asylum and protection mechanisms within the country (Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, 2023a).

Discussion

The cases of Ukrainian refugees and Turkish asylum seekers highlight the importance of existing networks, diaspora, relationships, and support systems. With changes in social environment and government, social networks become salient in situations of emergency and humanitarian crisis as relevant information on how to respond to crisis is often gathered from community sources and traditional knowledge by personal experience rather than from official sources (Aldrich, 2012; Burke et al., 2012; Field, 2017; Pidgeon et al., 2003). Policymakers should amplify and leverage existing social capital to facilitate the integration process and preparedness for emergency situations, which may involve developing community-based systems that tap into the solidarity within communities through initiatives that foster community engagement and creating platforms that facilitate sharing experiences and resources. Emergency management methods are not being utilized for this but would provide frameworks for effective communication, aid, sheltering, and community resilience as they relate to the migrant experience, regardless of whether the driver of displacement is conflict or hazard.

The complexities highlighted by the integration of Ukrainian refugees and Turkish asylum seekers underscore the urgent need for flexible, inclusive policies tailored to the diverse needs of displaced populations. There is a critical requirement for policies that streamline the asylum process, enhance legal and advocacy support, and ensure access to integration programs that are sensitive to the educational and professional backgrounds of asylum seekers. Moreover, the gender-sensitive approach and the need for childcare services underscore the importance of considering the unique vulnerabilities and needs of displaced populations, particularly women and children. Policymakers should work towards developing consistent, equitable legal frameworks and non-discriminatory policies that facilitate access to the labor market, support services, and increased financial assistance.

The integration process for educated Turkish asylum seekers in Germany has provided additional valuable insights into challenges for successful integration. One key lesson learned is the need for flexibility in the approach to integration processes. Moreover, the asylum process for Turkish individuals highlights the necessity for flexible asylum policies that are adaptable to the unique circumstances of diverse groups. Enhanced legal and advocacy support services are crucial in ensuring that asylum seekers understand their rights and the legal processes, potentially improving their chances of a favorable outcome. Likewise, there is a need for a nuanced understanding of the asylum and integration process, emphasizing the importance of tailored support services, the recognition of professional qualifications, and the facilitation of social and employment integration. These measures are crucial to enhancing the overall effectiveness of asylum protection and integration strategies in Germany, ensuring that all asylum seekers, regardless of their status or origin, receive the support they need to integrate successfully into German society.

The application of temporary protection status to Ukrainian refugees and the integration challenges faced by Turkish asylum seekers also highlights the importance of developing consistent, non-discriminatory policies that consider the needs and vulnerabilities of diverse groups. This includes clear definitions of eligibility criteria and rights. It offers valuable insights into a legal framework that ensures quick access to the local market, support services, and increased financial assistance. The implementation of TPD underscored the significance of equitable treatment and support for the displaced population. Policymakers should engage in developing and enforcing non-discriminatory policies, considering the needs and vulnerabilities of the displaced populations. This includes providing clear definitions of eligibility criteria, rights, and obligations essential for both host countries and displaced populations (Boucher, 2020; Czaika & De Haas, 2013; Helbling et al., 2020). The European Union and German approaches to addressing Ukrainian displacement can provide valuable lessons learned for policymakers and practitioners, including allowing refugees to access the labor market as soon as possible.

The atypical gender profile of Ukrainian refugees highlighted the need for a gender-sensitive approach, particularly in areas such as childcare protection and gender-based violence. As research shows, childcare services and facilities become crucial for integration into the Labor market, including language courses and ensuring the well-being of their children (Cheung & Phillimore, 2017), and these needs to be addressed within this policy framework. This case also emphasizes the importance of implementing measures to prevent and address gender-based violence (Freedman, 2016). This may include creating safe spaces, offering information about the risks of gender-based violence, and providing services for survivors in the language of a displaced person.

Pathways to permanent residency and citizenship are critical in providing displaced individuals with certainty and a roadmap for integration. The lack of streamlined procedures can leave asylum seekers and refugees in a state of limbo, underscoring the need for international collaboration and the development of common policies and standards across member states. This collaboration is essential for moving from ad hoc responses to a more structured and efficient approach to managing displacement and humanitarian crises, ensuring equitable treatment and support for all displaced populations.

Conclusion

The exploration of humanitarian responses, solutions, and lessons learned from the experiences of Ukrainian refugees and Turkish asylum seekers in Germany underscores a multifaceted approach to managing displacement crises. The necessity for tailored integration programs that address the diverse backgrounds, qualifications, and professional experiences of displaced individuals has been vividly illustrated through these cases. Specifically, the integration of Turkish asylum seekers, marked by their high educational and professional backgrounds, emphasizes the importance of providing personalized support services that encompass language training, legal assistance, mental health support, and recognition of professional qualifications.

The experiences drawn from both groups highlight the critical role of flexibility in asylum policies, suggesting that a one-size-fits-all approach is insufficient to meet the varied needs of different asylum seeker groups. Emergency management guidance could support the population and mitigate and reduce vulnerability through policy, to be able to serve displaced populations while being flexible and effective. Furthermore, community engagement and the leveraging of diaspora networks emerge as pivotal strategies in facilitating the integration process, providing not only practical support but also a sense of belonging and community for newly arrived asylum seekers. Moreover, the implementation of temporary protection status for Ukrainian refugees brings to light the significance of developing consistent, equitable legal frameworks that ensure quick access to support services and the labor market. This approach, coupled with gender-sensitive policies and early integration measures, can significantly enhance the long-term success and well-being of displaced individuals in their host countries.

The integration experiences of Ukrainian refugees and Turkish asylum seekers reveal comprehensive lessons for international disaster management, humanitarian response, and policy development. These include the importance of tailored integration programs, flexible asylum policies, community engagement, early integration measures, continuous monitoring and evaluation, and international collaboration. These insights underscore the need for adaptable, inclusive, and compassionate policies that recognize the unique challenges and contributions of displaced individuals, thereby enhancing the overall effectiveness of international disaster response mechanisms and promoting a more humane and equitable approach to global migration and asylum policies. The analysis also reveals the necessity for continuous monitoring, evaluation, and international collaboration to address the dynamic challenges faced by asylum seekers and refugees. By advocating for common policies and standards across member states, policymakers can minimize disparities in the treatment of displaced populations and foster a more unified and effective response to global displacement and humanitarian crises.

Considering these findings, it is imperative for international stakeholders to collaborate in crafting policies that not only address the immediate needs of displaced populations but also pave the way for their long-term integration and success. This collaboration should aim at establishing common policies and standards that ensure equitable treatment and support for all displaced individuals, regardless of their origin. The insights gained from the experiences of Ukrainian refugees and Turkish asylum seekers in Germany provide a blueprint for a humane, effective approach to global displacement and humanitarian crises, emphasizing the importance of adaptability, inclusiveness, and compassion in policy development. The goal should be to foster a global environment where displaced individuals are empowered to rebuild their lives with dignity, security, and hope.

References

Alachkar, M. (2023). The lived experiences of resilience among Syrian refugees in the UK: Interpretative phenomenological analysis. BJPsych Bulletin, 47(3), 133–139. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2022.16

Aldrich, D. P. (2012). Building resilience: Social capital in post-disaster recovery. The University of Chicago Press.

Andrews, J., Isański, J., Nowak, M., Sereda, V., Vacroux, A., & Vakhitova, H. (2023). Feminized forced migration: Ukrainian war refugees. Women’s Studies International Forum, 99, 102756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2023.102756

Artur, L. (2022). Vulnerability and resilience in a complex and chaotic context: Evidence from Mozambique. In D. Hihorst & G. Bankoff (Eds.), Why vulnerability still matters: The politics of disaster risk creation. Routledge.

Associated Press. (2024, January 20). Germany: Citizenship law could prompt 50,000 Turks to apply. Deutsche Welle. https://www.dw.com/en/germany-citizenship-law-could-prompt-50000-turks-to-apply/a-68040515

Aydiner, C., & Rider, E. (2022). Migration policies and practices at job market participation: Perspectives of highly educated Turks in the US, Canada and Europe. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 42(5/6), 399–415. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-02-2021-0044

Aydın, Y. (2016). The Germany-Turkey Migration Corridor: Refitting Policies for a Transnational Age (Migration Policy Institute). Transatlantic Council on Migration.

Barslund, M., Busse, M., Lenaerts, K., Ludolph, L., & Renman, V. (2017). Integration of Refugees: Lessons from Bosnians in Five EU Countries. Intereconomics, 52(5), 257–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10272-017-0687-2

Bastaki, J. (2018). Temporary Protection Regimes and Refugees: What Works? Comparing the Kuwaiti, Bosnian, and Syrian Refugee Protection Regimes. Refuge, 34(2), 73–84. https://doi.org/10.7202/1055578ar

Bőgel, G., Brzozowski, J., Czerska-Shaw, K., & Mátyás, L. (2023). Refugees: Economic Costs and Eventual Benefits. In L. Mátyás (Ed.), Central and Eastern European Economies after the Ukrainian War: Between a Rock and Hard Place (pp. 1–52).

Bohnet, H., Cottier, F., & Hug, S. (2021). Conflict versus Disaster-induced Displacement: Similar or Distinct Implications for Security? Civil Wars, 23(4), 493–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698249.2021.1963586

Boucher, A. K. (2020). How ‘skill’ definition affects the diversity of skilled immigration policies. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(12), 2533–2550. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1561063

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brücker, H., Ette, A., Grabka, M. M., Kosyakova, Y., Niehues, W., Rother, N., Spieß, C. K., Zinn, S., Bujard, M., Cardozo, A., Décieux, J. P., Maddox, A., Milewski, N., Naderi, R., Sauer, L., Schmitz, S., Schwanhäuser, S., Siegert, M., & Tanis, K. (2023). Ukrainian refugees in Germany: Fleeing, arriving and living. Kurzanalyse Des BAMF-Forschungszentrums / BAMF-Kurzanalyse. https://doi.org/10.48570/BAMF.FZ.KA.04/2022.EN.2023.UKRKURZBERICHT.1.0

Brücker, H., Ette, A., Grabka, M. M., Kosyakova, Y., Niehues, W., Rother, N., Spieß, C. K., Zinn, S., Bujard, M., Cardozo Silva, A. R., Décieux, J. P., Maddox, A., Milewski, N., Sauer, L., Schmitz, S., Schwanhäuser, S., Siegert, M., Steinhauer, H., & Tanis, K. (2023). Ukrainian Refugees in Germany: Evidence From a Large Representative Survey. Comparative Population Studies, 48. https://doi.org/10.12765/CPoS-2023-16

Brücker, H., Ette, A., Grabka, M. M., Kosyakova, Y., Niehues, W., Rother, N., Spieß, C. K., Zinn, S., Bujard, M., Décieux, J. P., Maddox, A., Schmitz, S., Schwanhäuser, S., Siegert, M., & Steinhauer, H. W. (2023). Ukrainian Refugees: Nearly Half Intend to Stay in Germany for the Longer Term. DIW Wochenbericht. https://doi.org/10.18723/DIW_DWR:2023-28-1

Burke, S., Bethel, J. W., & Britt, A. F. (2012). Assessing Disaster Preparedness among Latino Migrant and Seasonal Farmworkers in Eastern North Carolina. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9(9), 3115–3133. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9093115

Carrera, S., & Ineli Cigar, M. (2023). EU responses to the large-scale refugee displacement from Ukraine: An analysis on the temporary protection directive and its implications for the future EU asylum policy. European University Institute.

CEDEFOP. (2022, June 9). Germany’s response to the integration of Ukrainian refugees in VET and the labour market. https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/news/germanys-response-integration-ukrainian-refugees-vet-and-labour-market

Cheung, S. Y., & Phillimore, J. (2017). Gender and Refugee Integration: A Quantitative Analysis of Integration and Social Policy Outcomes. Journal of Social Policy, 46(2), 211–230. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279416000775

Cho, H., & Lee, J.-S. (2015). The influence of self-efficacy, subjective norms, and risk perception on behavioral intentions related to the H1N1 flu pandemic: A comparison between Korea and the US: Cross-national comparison of behavioral intention. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 18(4), 311–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12104

Ciaramella, M., Monacelli, N., & Cocimano, L. C. E. (2022). Promotion of Resilience in Migrants: A Systematic Review of Study and Psychosocial Intervention. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 24(5), 1328–1344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-021-01247-y

Cimino, F., & Degani, P. (2023). Gendered impacts of the war in Ukraine: Identifying potential, presumed or actual women victims of trafficking at the Italian borders. Frontiers in Human Dynamics, 5, 1099208. https://doi.org/10.3389/fhumd.2023.1099208

Corbin, T. B. (2021). Displacement after disaster: Challenges and opportunities responding to Puerto Rican evacuees in Central Florida after Hurricane Maria. Journal of Emergency Management, 19(8), 123–134. https://doi.org/10.5055/jem.0624

Council of the EU. (2023, November). Refugees from Ukraine in the EU. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/infographics/ukraine-refugees-eu/

Czaika, M., & De Haas, H. (2013). The Effectiveness of Immigration Policies. Population and Development Review, 39(3), 487–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00613.x

Dadush, U., & Niebuhr, M. (2016, April 22). The Economic Impact of Forced Migration. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/2016/04/22/economic-impact-of-forced-migration-pub-63421

Desiderio, M. V., & Hooper, K. (2022). Why the European Labor Market Integration of Displaced Ukrainians Is Defying Expectations. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/news/european-labor-market-integration-displaced-ukrainians

Dhingra, R., & Roehse, S. (2023). A roadmap for European asylum and refugee integration policy: Lessons from the Ukraine response. Brookings Institute. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/a-roadmap-for-european-asylum-and-refugee-integration-policy/

Donner, W., & Rodríguez, H. (2008). Population composition, migration and inequality: The influence of demographic changes on disaster risk and vulnerability. Social Forces, 87(2), 1089–1114. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.0.0141

Duszczyk, M., Górny, A., Kaczmarczyk, P., & Kubisiak, A. (2023). War refugees from Ukraine in Poland – one year after the Russian aggression. Socioeconomic consequences and challenges. Regional Science Policy & Practice, 15(1), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/rsp3.12642

Duvar English. (2020, January 11). 47.4 percent of Turkish asylum seekers granted protection in Germany in 2019. https://www.duvarenglish.com/human-rights/2020/01/11/47-4-percent-of-turkish-asylum-seekers-granted-protection-in-germany-in-2019

Esnard, A.-M., & Sapat, A. (2014). Displaced by disaster: Recovery and resilience in a globalizing world. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations. (2021, August 24). Germany. https://civil-protection-humanitarian-aid.ec.europa.eu/what/civil-protection/national-disaster-management-system/germany_en

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. (2023). Fleeing Ukraine: Displaced people’s experiences in the EU: Ukrainian survey 2022. Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2811/39974

Fasani, F., Frattini, T., & Minale, L. (2022). (The Struggle for) Refugee integration into the labour market: Evidence from Europe. Journal of Economic Geography, 22(2), 351–393. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbab011

Fassmann, H., & İçduygu, A. (2013). Turks in Europe: Migration Flows, Migrant Stocks and Demographic Structure. European Review, 21(3), 349–361. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1062798713000318

Federal Office for Migration and Refugees. (2022). The Migration Report 2020. https://www.bamf.de/EN/Themen/Forschung/Migrationsberichte/migrationsberichte-node.html

Federal Office for Migration and Refugees. (2023a). Aktuelle Zahlen zu Asyl in Deutschland—Dezember 2023 [Current figures on asylum in Germany—December 2023]. https://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Statistik/AsylinZahlen/aktuelle-zahlen-dezember-2023.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=4

Federal Office for Migration and Refugees. (2023b). The stages of the German asylum procedure: An overview of the individual procedural steps and the legal basis. https://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/EN/AsylFluechtlingsschutz/Asylverfahren/das-deutsche-asylverfahren.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=23

Feinstein, S., Poleacovschi, C., Drake, R., & Winters, L. A. (2022). States and Refugee Integration: A Comparative Analysis of France, Germany, and Switzerland. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 23(4), 2167–2194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-021-00929-8

Field, J. (2017). What is appropriate and relevant assistance after a disaster? Accounting for culture(s) in the response to Typhoon Haiyan/Yolanda. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 22, 335–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.02.010

Freedman, J. (2016). Sexual and gender-based violence against refugee women: A hidden aspect of the refugee “crisis.” Reproductive Health Matters, 24(47), 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rhm.2016.05.003

Gaillard, J. C. (2010). Vulnerability, capacity and resilience: Perspectives for climate and development policy. Journal of International Development, 22(2), 218–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1675

German Federal Statistical Office. (2022). Foreign population by place of birth and selected citizenships [dataset]. https://www.destatis.de/EN/Themes/Society-Environment/Population/Migration-Integration/Tables/foreigner-place-of-birth.html

Göler, D. (2020). Places and Spaces of the Others. A German Reception Centre in Public Discourse and Individual Perception. In B. Glorius & J. Doomernik (Eds.), Geographies of Asylum in Europe and the Role of European Localities (pp. 69–91). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25666-1_4

Gurer, C. (2019). Refugee Perspectives on Integration in Germany. American Journal of Qualitative Research, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.29333/ajqr/6433

Haase, A., Arroyo, I., Astolfo, G., Franz, Y., Laksevics, K., Lazarenko, V., Nasya, B., Reeger, U., & Schmidt, A. (2024). Housing refugees from Ukraine: Preliminary insights and learnings from the local response in five European cities. Urban Research & Practice, 17(1), 139–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2023.2225333

Hageboutros, J. (2016). The Bosnian Refugee Crisis: A Comparative Study of German and Austrian Reactions and Responses. Swarthmore International Relations Journal, 1, 50–60. https://doi.org/10.24968/2574-0113.1.12

Hanewinkel, V., & Oltmer, J. (2018, December 1). Germany’s Migration Policies. Bundeszentrale Für Politische Bildung. https://www.bpb.de/themen/migration-integration/laenderprofile/english-version-country-profiles/262811/germany-s-migration-policies/

Hanson-Easey Scott, Bi, P., & Hansen, A. (2015). Risk Communication Planning with Culturally and Linguistically diverse communities (CALD): An all-hazards risk communication toolkit for emergency service agencies. South Australian Fire and Emergency Services Commission. http://rgdoi.net/10.13140/RG.2.2.15609.90727

Hegedüs, J., Somogyi, E., Teller, N., Kiss, A., Barbu, S., & Wetzstein, S. (2023). Housing of Ukrainian Refugees in Europe Options for Long-Term Solutions (Research on Long-Term Housing of Ukrainian Refugees in Europe). Habitat for Humanity International. https://www.habitat.org/emea/housing-ukrainian-refugees-europe

Heidbreder, E. G. (2024). Withering the exogenous shock: EU policy responses to the Russian war against Ukraine. West European Politics, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2023.2291971

Helbling, M., Simon, S., & Schmid, S. D. (2020). Restricting immigration to foster migrant integration? A comparative study across 22 European countries. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(13), 2603–2624. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1727316

Hilhorst, D. (2022). Humanitarianism: Navigating between resilience and vulnerability. In G. Bankoff & D. Hihorst (Eds.), Why vulnerability still matters: The politics of disaster risk creation. Routledge.

Hossain, A., Bartolucci, A., & Hirani, S. A. A. (2023). Editorial: Conflicts and humanitarian crises on displaced people’s health. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1234576. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1234576

Ilcan, S., Rygiel, K., & Baban, F. (2018). The ambiguous architecture of precarity: Temporary protection, everyday living and migrant journeys of Syrian refugees. International Journal of Migration and Border Studies, 4(1/2), 51. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMBS.2018.091226

Jaspars, S. (2022). Resilience, food security, and the abandonment of crisis-affected populations. In G. Bankoff & D. Hihorst (Eds.), Why vulnerability still matters: The politics of disaster risk creation. Routledge.

Karaçay, A. B. (2023). Temporary Protection Regimes in Türkiye and Germany: Comparing Bosnian Syrian and Ukrainian Refugee Protection Regimes. İmgelem, 7(13), 561–586. https://doi.org/10.53791/imgelem.1368731

Kashyap, V. (2014). Role of Spirituality and Resilience Among the Tibetan Refugees in Exile (India). Review of Research Journal, 3(11).

Kelman, I., Gaillard, J. C., Lewis, J., & Mercer, J. (2016). Learning from the history of disaster vulnerability and resilience research and practice for climate change. Natural Hazards, 82(S1), 129–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-016-2294-0

Knox, C. C., & Haupt, B. (Eds.). (2020). Cultural competency for emergency and crisis management: Concepts, theories and case studies. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Koike, K. (2011). Forgotten and unattended: Refugees in post-earthquake Japan. Forced Migration Review, 46–47.

Kozman, R., Mussie, K. M., Elger, B., Wienand, I., & Jotterand, F. (2024). Ethical Challenges in Oral Healthcare Services Provided by Non-Governmental Organizations for Refugees in Germany. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-023-10327-7

Lloyd, A. T., & Sirkeci, I. (2022). A Long-Term View of Refugee Flows from Ukraine: War, Insecurities, and Migration. MIGRATION LETTERS, 19(4), 523–535. https://doi.org/10.33182/ml.v19i4.2313

Luna, F. (2009). Elucidating the concept of vulnerability: Layers not labels. IJFAB: International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics, 2(1), 121–139. https://doi.org/10.3138/ijfab.2.1.121

Marlowe, J., & Bogen, R. (2015). Young people from refugee backgrounds as a resource for disaster risk reduction. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 14, 125–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2015.06.013

Marlowe, J., Neef, A., Tevaga, C. R., & Tevaga, C. (2018). A New Guiding Framework for Engaging Diverse Populations in Disaster Risk Reduction: Reach, Relevance, Receptiveness, and Relationships. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 9(4), 507–518. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13753-018-0193-6

Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative Content Analysis. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(2), 20. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-1.2.1089

Mayring, P. (2019). Qualitative Content Analysis: Demarcation, Varieties, Developments. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 20(3), 16. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-20.3.3343

Menéndez, A. J. (2016). The Refugee Crisis: Between Human Tragedy and Symptom of the Structural Crisis of European Integration. European Law Journal, 22(4), 388–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/eulj.12192

Migration Data Portal. (2023). Forced migration or displacement [dataset]. https://www.migrationdataportal.org/themes/forced-migration-or-displacement

Morgan, D. L. (1993). Qualitative Content Analysis: A Guide to Paths not Taken. Qualitative Health Research, 3(1), 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973239300300107

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2023). What are the integration challenges of Ukrainian refugee women? (Policy Responses: Ukraine Tackling the Policy Challenges). https://www.oecd.org/ukraine-hub/policy-responses/what-are-the-integration-challenges-of-ukrainian-refugee-women-bb17dc64/

Phillimore, J., Block, K., Bradby, H., Ozcurumez, S., & Papoutsi, A. (2023). Forced Migration, Sexual and Gender-based Violence and Integration: Effects, Risks and Protective Factors. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 24(2), 715–745. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-022-00970-1

Pidgeon, N. F., Kasperson, R. E., & Slovic, P. (Eds.). (2003). The social amplification of risk. Cambridge University Press.

Quinn, E. (2016). The Refugee and Migrant Crisis: Europe’s Challenge. Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, 105(419), 275–285.

Reuters. (2022a, May 14). Over 700,000 refugees from Ukraine registered in Germany, Welt am Sonntag reports. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/over-700000-refugees-ukraine-registered-germany-welt-2022-05-14/

Reuters. (2022b, December 15). Ukrainian refugees feel welcome in Germany, 37% keen to stay permanently: Survey. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/ukrainian-refugees-feel-welcome-germany-37-keen-stay-permanently-survey-2022-12-15/

Richtmann, M. (2022, April 14). Ukraine war: How Germany pays for refugees. Deutsche Welle. https://www.dw.com/en/ukraine-war-how-germany-pays-for-refugees/a-61479216

Riger, S., & Sigurvinsdottir, R. (2016). Thematic Analysis. In L. A. Jason & D. S. Glenwick (Eds.), Handbook of methodological approaches to community-based research: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods (pp. 33–41). Oxford University Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2016-04165-004

Schuetze, C. F. (2024, January 19). German lawmakers agree to ease path to citizenship. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/01/19/world/europe/german-citizenship-law.html

Siddiqi, A. (2022). Disaster studies and its discontents: The postcolonial state in hazard and risk creation. In G. Bankoff & D. Hihorst (Eds.), Why vulnerability still matters: The politics of disaster risk creation. Routledge.

Sirkeci, I. (2017). Türkiye’s refugees, Syrians and refugees from Turkey: A country of insecurity. Migration Letters, 14(1), 127–144. https://doi.org/10.59670/ml.v14i1.321

Spittles, B., & Fozdar, F. (2008). Understanding emergency management: A dialogue between emergency management sector and CALD communities. Fire and Emergency Services Authority of Western Australia. https://researchportal.murdoch.edu.au/esploro/outputs/report/Understanding-emergency-management-A-dialogue-between/991005544326807891

Stockemer, D., Niemann, A., Unger, D., & Speyer, J. (2020). The “Refugee Crisis,” Immigration Attitudes, and Euroscepticism. International Migration Review, 54(3), 883–912. https://doi.org/10.1177/0197918319879926

Stockholm Center for Freedom. (2022, December 23). Number of Turkish asylum seekers in Germany increased by 216 percent in 2022: Report. https://stockholmcf.org/number-of-turkish-asylum-seekers-in-germany-increased-by-216-percent-in-2022-report/

Thijssen, L., Lancee, B., Veit, S., & Yemane, R. (2021). Discrimination against Turkish minorities in Germany and the Netherlands: Field experimental evidence on the effect of diagnostic information on labour market outcomes. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 47(6), 1222–1239. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1622793

Topcu, E. (2023, August 14). Germany sees surge in Turkish asylum seekers. Deutsche Welle. https://www.dw.com/en/germany-sees-surge-in-turkish-asylum-seekers/a-66512173

Uekusa, S. (2019). Methodological Challenges in Social Vulnerability and Resilience Research: Reflections on Studies in the Canterbury and Tohoku Disasters*. Social Science Quarterly, 100(4), 1404–1419. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12617

Uekusa, S., & Matthewman, S. (2017). Vulnerable and resilient? Immigrants and refugees in the 2010–2011 Canterbury and Tohoku disasters. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 22, 355–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.02.006

UN News. (2023, October 23). Over 114 million displaced by war, violence worldwide. https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/10/1142827

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). (n.d.). Refugee Data Finder [dataset]. www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/

Weitz, V. (2022, July 23). Ukrainian refugees welcome in Germany, but uncertain about returning home. Deutsche Welle. https://www.dw.com/en/ukrainian-refugees-welcome-in-germany-but-uncertain-about-returning-home/a-62544330

Xhardez, C., & Soennecken, D. (2023). Temporary Protection in Times of Crisis: The European Union, Canada, and the Invasion of Ukraine. Politics and Governance, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v11i3.6817

Xie, M., & Chao, C. (2022). Race and Cultural Taboo: Refugee Disaster Vulnerability and Resilience. In G. Luurs (Ed.), Handbook of research on communication strategies for taboo topics (pp. 104–125). Information Science Reference.