7 Nations Among Nations: Strengthening Tribal Resilience and Disaster Response

Rebecca Morgenstern Brenner, MPA; Danielle J. Mayberry, JD; Kelbie R. Kennedy, JD; and Marc Anthonisen, MPA

Authors

Rebecca Morgenstern Brenner, MPA, Senior Lecturer, Cornell University

Danielle J. Mayberry, JD, (enrolled tribal citizen of Te-Moak Tribe of Western Shoshone), Principal Law Clerk, Saint Regis Mohawk Tribal Courts

Kelbie R. Kennedy, JD, (enrolled tribal citizen of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma), Tribal Emergency Management Advocate

Marc Anthonisen, MPA, Advisor, Climate Smart Communities Task Force, Town of New Lebanon, NY

Keywords

adaptive capacity, resilience, Tribal Nations, indigenous, tribal jurisdiction, emergency management, climate change

Abstract

Tribal Nations have their own leadership, laws, rules, and regulations but still must work with the neighboring international, tribal, federal, and local government jurisdictions on adaptation and response to disasters and climate change. The impact of disasters on indigenous populations is different from that on communities in other local governments. Often there is an intersection of jurisdictions due to federal Indian jurisprudence. Existing policy leaves considerable question as to which government entity—tribal, federal, state, or local—has jurisdiction. This is exacerbated by the limited capacity entities may have to respond to emergencies. Jurisdictional uncertainties, cultural differences, and inconsistent tribal-state power balances may have contributed to indigenous populations being disproportionately impacted by emergencies. This raises the questions: How do we develop equitable and adaptive policies across political boundaries in a changing global climate? What are potential pathways to improve coordination between a myriad of governments within a controversial power structure in a time of increasing climate stresses and with limitations and challenges of local governments and jurisdictions? Written with two tribal citizens, this Chapter investigates how to build a more resilient community by investing in policy, planning, and leadership development as well as how to manage disasters with international boundaries for multiple government jurisdictions. Interviews were conducted with the leadership teams of the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe and Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma and inform four recommendations regarding funding, jurisdiction, education, and coordination. This chapter is intended to advise any leadership team on how to collaborate with Tribal Nations to lean into and build adaptive capacity and resilience for all.

Introduction

Once a disaster strikes, it is too late to start the conversation on response strategy and how this relates to crossing jurisdictions. In discussing political and planning considerations that extend beyond international boundaries, there are also neighboring and interdependent jurisdictions that are Tribal Nations (National Congress of American Indians 2020). In this chapter we will use the term Tribal Nation, to refer to federally recognized tribes, Indian tribal governments, Indian Nations, and Tribes. The concept “Tribal Nation” is the most inclusive term to use when referencing tribal governments across the United States. It is also the term that many Tribal Nations use when working with the United States federal government to reinforce their nation-to-nation relationship (National Congress of American Indians 2020).

Today, there are 574 federally recognized Indian tribes within the United States (Indian Affairs, n.d.). All of these Tribal Nations have their own governments, leadership, laws, rules, and regulations but still must work with federal and local governments in disaster and climate change matters. Internally, Tribal Nations are unique in and of themselves: each has differences in leadership, structure, and governance. Externally, Tribal Nations have independent relationships with neighboring international, tribal, federal, state, and local government entities with established political boundaries.

The impacts of disasters on Tribal Nations are different from the impact on other communities. The complexity of jurisdiction due to federal Indian jurisprudence and policy leaves considerable question as to which government entity—tribal, federal, state, or local —has jurisdiction to respond to emergencies. There are additional challenges related to which administration has the resources and capacity to respond. In the United States, Tribal Nations have largely been left out of consistent annual federal funding that states receive to build their emergency management capabilities and capacities, leaving many without the necessary emergency management staff needed to build resiliency. Local governments similarly have limited capacity and resources to respond to disasters. They also have limited investments in environmental mitigation to manage disasters proactively. Jurisdictional uncertainties, cultural differences, and troubled tribal-state relations potentially contribute to Tribal Nations and tribal communities being disproportionately impacted by and during disaster related emergencies. For example, the management of resources by Tribal Nations such as water has become vital in combating climate change. The United States Supreme Court has determined that Tribal Nations have water rights under the Winters doctrine to ensure that reservations are livable and productive (Arizona v. Navajo Nation 2023). However, in using this analysis the Supreme Court looks to the applicable treaty and its trust responsibility to determine whether the federal government is required to do so (Arizona v. Navajo Nation 2023).

Indigenous people account for 6.2 percent of the global population in 2024. Currently, there are over 476 million indigenous people living in 90 countries around the world. The indigenous nations account for more than 5,000 distinct groups. Indigenous people also have a strong connection to their land bases that existed prior to colonization and have a distinct culture, social, economic, and political systems (United Nations, n.d.). With a strong connection to the land and the ecological system, indigenous communities should have self-determination for investments in response and recovery to climate related disasters. However, disaster and emergency management practices are likely influenced by the actions or decisions of external government systems for response and recovery. Indigenous communities therefore have an added burden of coordinating with international governing systems. Any neighboring international, federal, state, and local government entities may influence how indigenous communities respond to disasters or their ability to invest in adaptive capacity (Yohe and Tol 2002; Smit and Wandel 2006).

Local governments, both within different Tribal Nations and within adjacent countries, have limitations on their own capacity to respond to and prepare for increasing climate related disasters. It is critical to understand the limitations and challenges that local government faces. This includes understanding how to include the whole community in decision-making for future planning and to provide pathways for leaders and the community to work together (FEMA 2015). Together, the whole community can invest in developing policies that prepare for climate change before it happens. Building resilience includes encouraging vulnerable and marginalized community members to be proactive in planning (IPCC 2022).

To better understand the challenges that Tribal Nations face, two tribal communities – the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe which is adjacent to the state of New York, and the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma which is adjacent to the state of Oklahoma, shared the challenges their decision-makers and leaders face in preparing for an increase in disasters with a changing climate system. These two Tribal Nations have different governing structures, jurisdictional boundaries, relationships with surrounding governments, and represent two different geographies with different environmental disasters. Understanding and interviewing these perspectives can help inform broader issues of emergency management that Tribal Nations may face. Being aware of the sensitivities and vulnerabilities to climate disasters (Turner et al. 2003) can help identify lessons that can be used by other Tribal Nation communities managing disasters and international boundaries.

A series of interviews were conducted with each Nation’s leadership teams. These interviews inform four key recommendations for the neighboring local, state, regional, federal, and international community and government partners should consider in developing their emergency management plans and processes. Overall, while two different Tribal Nations were interviewed, as explained below, each Nation is its own independent government, and each have a different structure therefore these recommendations should be the starting point for a conversation with neighboring Tribal Nations rather than any one Tribal Nation speak for all 574 federally recognized Nations across the country. This chapter also provide a deep discussion of the background and history that frames the challenges Tribal Nations face and is a critical and inherent part of the decision-making process each Tribal Nation uses to inform their pathways and processes for preparedness, response, recovery, mitigation, and adaption to disasters.

Tribal Nations and Emergency Management

In United States and Canada, Tribal Nations range from Alaska to the Southwest and from the Great Plains to the eastern seaboard. Historically, Tribal Nations were among the earliest democracies in the world. Tribal Nations enjoyed full sovereignty and were organized with distinct internal societies responsible for governance over specific aspects of tribal life (EagleWoman and Leeds 2019). In many regions in North America, Tribal Nations joined with each other to form larger communities, military alliances, and commercial networks.

Each of the 574 federally recognized Indian tribes or Tribal Nations within the United States is unique and guided by their own distinct culture and independent governance structure. Many Tribal Nations are organized under the Indian Reorganization Act (“Protection of Indians and Conservation of Resources, 25 U.S. Code §461 et Seq.” 2011). Often, Tribal Nations are organized under constitutions and other bodies of law and have found a way to implement traditional systems of government within their contemporary governments. The relationship between the contemporary Tribal Nations and the federal government in the United States is defined by treaties and previous federal Indian policies set forth by the executive and legislative branches of government and the United States Supreme Court. These policies and decisions play a part in how Tribal Nations interact with the federal government as well as with state and local governments. They also impact how Tribal Nations can access federal funding and resources.

Each Tribal Nation’s government interacts with local and state government and in some cases, a Tribal Nation is located across an international boundary such as those between the United States and Mexico or Canada. As of 2018, Tribal Nation lands shared 260 miles of international borders, which is 100 miles longer than California’s border with Mexico (NCAI 2020). With the addition of newly federally recognized tribes and the increase of tribal lands since then, this number has likely grown and continues to evolve. Tribal Nations interact with foreign governments and the nature of those power dynamics varies.

Further, different Tribal Nations have distinct relationships with neighboring international and state boundaries. Each Tribal Nation must manage local, state, federal, and international relationships that completely differ from other Tribal Nations. The Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe has different relationships with the State of New York as well as the Provinces of Quebec and Ontario as well as with the federal governments of the United States and Canada. The relationship the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma differs with the state of Oklahoma, local counties, the Republic of Ireland, and the United States. Each Tribal Nation manages and holds different collaborations, and they likely even differ among local, state, and federal level. Understanding the comparison to see what lessons we can learn from both communities can better inform policy tools to build resilience and adaptive capacity of these communities with the growing threat of disasters due to climate change.

The interviews with these two Tribal Nations look for replicable consistencies to empower international and local leaders to work together. It is the differences between these cases that provide a lens into the range of policy recommendations needed. Climate change will increase pressure on Tribal Nations to coordinate more externally with neighboring governments as well as reevaluate and invest in processes and procedures internally.

Understanding the History of Tribal Sovereignty, Self-Determination, and the Federal Indian Policies that Shaped Tribal Disaster Response

Since first contact, United States law and policies regarding Tribal Nations have fluctuated, often being described as a pendulum swinging between two opposing policy stances (EagleWoman and Leeds 2019). Laws or policies have either aided the Tribal Nations in governmental self-determination or aggressively promoted the destruction of Tribal Nations through termination policies (Mayberry 2019). This historical divergence in Tribal Nations self-determination still drives the challenge Tribal Nations face in building policies and laws that frame response, recovery, and investments to climate related disasters. Understanding historical inequities is critical to identify the gaps and investments needed to build toward more equitable policies and laws within the changing human and natural environmental system.

The United States’ first official policy can be traced to Great Britain and the international practice of treaty making between Europeans and Tribal Nations in North America (Cohen 1942). During this era, the United States entered over four hundred treaties with Tribal Nations (EagleWoman and Leeds 2019). The primary motivation for the United States to enter treaties was to secure land cessions. The federal government’s approach was driven by the question of how to deal with the “Indian problem” (Cohen 1942). Throughout the 1820s, various southeastern states called for the removal of Tribal Nations from within their borders (Cohen 1942). In 1828, President Andrew Jackson called for the removal of Tribal Nations from the southeast. With Jackson’s support, Congress enacted the Indian Removal Act, allowing for the relocation of Tribal Nations to lands west of the Mississippi River (Cohen 1942).

The end of the Removal Era ushered in the Reservation Era. To resolve the “Indian problem,” efforts were made by the federal government to assimilate Indians into American society (Cohen 1942). Reservations were seen as the solution to attain the ultimate goal which was to obtain landholdings from Tribal Nations. Mayberry 2019 explains how federal officials began instituting Courts of Indian Offenses on the reservations, except for the Five Civilized Tribes, the Tribal Nations of New York, the Osage, the Pueblos, and the Eastern Cherokee and was reinforced with the launch of federal funding in 1879 for Indian boarding schools. The beginning of government run boarding schools can be traced to the Superintendent of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, Richard Henry Pratt. The philosophy for educating Indian students was described by Richard Henry Pratt as “kill the Indian, save the man.” At the boarding schools, Indian children were subjected to violence, physical and sexual abuse, neglect, and rigid forms of psychological and physical discipline (Mayberry 2019). This aggressive reeducation toward assimilation of Indian students dissected historical knowledge and connection to their regional natural ecological system (Cohen 1942).

Following the Civil War, the communal ownership of property by Tribal Nations appeared to be a significant barrier to assimilation (Mayberry 2019). Under assimilationist reasoning, if Indians adopted civilized life, they would not need large areas of land. The break-up of Indian land also had the effect of freeing up Indian lands for white settlers. In 1887, Congress passed the General Allotment Act, also known as the Dawes Act, beginning the Allotment Era (Cohen 1942). The Dawes Act divided reservation land tracts into smaller parcels. During this time, 65% of tribal lands were transferred to non-Indians (Cohen 1942). The Dawes Act did not apply to all Tribal Nations; for instance, the Seneca Nation was exempted (Mayberry 2019). This led to the State of New York establishing the Whipple Commission in 1888, tasked with investigating the status of the Indians within New York (Mayberry 2019).

In the mid-1920s, federal Indian policies shifted to restoring the recognition of Indian self-rule (EagleWoman and Leeds 2019). The catalyst for change began in 1928 with the findings of the Meriam Report (Meriam et al. 1928). The report found that “an overwhelming majority of the Indians are poor, even extremely poor, and they are not adjusted to the economic and social system of the white person” (Mayberry 2019). During this time, the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 (IRA) was passed which enabled Tribal Nations to exercise powers of limited self-government but did not end federal involvement in tribal affairs (“Records Relating to the Indian Reorganization Act (Wheeler–Howard Act)” 2023).

The IRA provided a process for Tribal Nations to reorganize their governments by adopting written constitutions. Mayberry (2019) explains how this led to a divergence. By the end of World War II, the United States hit its economic stride, but American Indians were left behind. During this time, Indians experienced the highest rates of unemployment and suicide, as well as the lowest incomes and life expectancies in their history. The past policies promoting Indian self-rule were considered a failure.

Once again, the federal government began transitioning to assimilation type policies, ushering in the Termination Era in the 1950s (EagleWoman and Leeds 2019). The Termination Era refers to actions by the United States government to eliminate obligations to indigenous communities through a combination of relocation, reassessing tribal status, and Public Law 280. The government’s termination policy included the eventual transfer of civil and criminal jurisdiction to state governments and courts. Judge Garrow, 2019, expanded on the role between New York State and the federal government. New York State was constantly in conflict with the federal government over supreme control over Haudenosaunee land, arising out of the State’s assumption of a self-defined role as guardian of the Indians. New York State hoped that through assimilation Tribal Nations would eventually hold land in severalty, abandon present restrictions against ownership by non-Indians as do western tribes and transition, as Garrow 2019 explained “…from hermithood to the vigorous and responsible citizenship assured by their intelligence, independence, and courage”. However, much confusion surrounded the general question of the State’s power to legislate for Indians living on the reservation. Judge Garrow shared that in 1942, the Second Circuit addressed this matter in United States v. Forness where the Seneca Nation attempted to cancel a lease in the City of Salamanca for non-payment. The Second Circuit determined, “state law cannot be invoked to limit the rights in lands granted by the United States to the Indians, because state law does not apply to Indians without the consent of the United States” (Garrow 2019).

Forness led to the creation of the Joint Legislative Committee on Indian Affairs, which in turn led to the 1948 grant by Congress of concurrent criminal jurisdiction to New York State and a similar grant of partial civil jurisdiction in 1950 (Garrow 2019). Congress took similar action regarding other states as well. In 1953, Congress enacted Public Law 280, delegating criminal jurisdiction to California, Minnesota, Nebraska, Oregon, Wisconsin, and Alaska, with other states later allowed to gain partial jurisdiction (Mayberry 2019). Currently, the majority of states are not Public Law 280 states.

EagleWoman and Leeds (2019) further explained how urban Indians were inspired to arrange protest activities against the federal control over tribal communities and the termination policy during the civil rights movement in the 1960s in the United States. In response, President Richard Nixon delivered a Special Message on Indian Affairs to the United States Congress on July 8, 1970. President Nixon called on Congress to encourage Indian self-determination. One of the seminal pieces of legislation was the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 (S.1017 1975). EagleWoman and Leeds 2019 continued to explain how this statute and others enacted since have encouraged tribal government administration of services to tribal citizens with the intention of lessening Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) control over tribal communities. The current era of United States Indian policy remains the Indian Self-Determination Era. This is the policy framework that Tribal Nations need to work within to develop their own adaptive capacity to manage disaster recovery and build resilience.

The United States Supreme Court has also played a leading role in developing federal Indian law and shaping the policies directed towards the relationship between the federal government and Tribal Nations. This foundation is defined by three Supreme Court decisions authored by Chief Justice John Marshall in the early 1800s. These decisions are known as the “Marshall Trilogy” (Cohen 1942). In the first case, Johnson v. M’Intosh, the Supreme Court held that Tribal Nations held rights of occupancy to Indian land; however, the Court also determined that the European nations “discovery” claims held superior title to the same lands (Johnson v. M’Intosh 1823). Therefore, the United States, as successor to Great Britain, obtained superior title to all Indian land. In the next case, Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, the Court held that the Cherokee Nation was a “domestic dependent nation.” The Court defined the relationship between the Tribal Nations and the United States as “resembl[ing] that of a ward to his guardian” (Cherokee Nation v. Georgia 1831). The final case of the Marshall Trilogy, Worcester v. Georgia, involved a habeas petition brought by Samuel Worcester, a missionary (Worcester v. Georgia 1832). In Worcester, the Court defined the origin of the federal trust relationship by finding a relationship of an Indian tribe to the United States is based upon the “settled doctrine of the law of Nations” (Worcester v. Georgia 1832).

Tribal Nations and federal Indian law are mostly seen as a domestic part of American law; however, the foundations of federal Indian law are built on the “The Law of the Nations,” the field now known as international law (Eisner 2024). The Law of the Nations, a treatise by Emer de Vattel, is a central influence in Worcester. Eisner explains how Chief Justice Marshall cited Vattel as an authority on the law of nations in Europe in the Marshall Trilogy and that applying the law of nations to federal Indian law suggests not only that Tribal Nations have a right to self-government but that the same law of nations that governs relations among European states also protects tribal sovereignty. “Law of nations principles of sovereignty, which limit the reach of Congress’s power in foreign countries, also apply to Native Nations…Tribes enjoy a power to rule themselves that no other governmental body – state or federal – may usurp.” However, this broad interpretation Eisner shared envisioned in Worcester in conjunction with the undefined plenary authority Congress exercises in Indian affairs has created convoluted Supreme Court case law. For example, in 2022, Justice Kavanaugh writing for the majority in Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta, wrote “the general notion drawn from Chief Justice Marshall’s opinion in Worcester v. Georgia has yielded to closer analysis” and that “a reservation was in many cases a part of the surrounding State or Territory, and subject to its jurisdiction except as forbidden by federal law” (Oklahoma v. Castro-Huerta, 2022). In another matter, Haaland v. Brackeen, Justice Barrett’s majority opinion included the following: “We have often sustained Indian legislation without specifying the source of Congress’s power, and we have insisted that Congress’s power has limits without saying what they are” (Eisner 2024).

This frame that the Courts have determined set precedent for how Tribal Nations can manage their political boundaries. As a result, neighboring states and local governments can influence or impede the adaptive capacity of the Tribal Nations. Recent Court decisions and future decisions beg the question about power and authority to cross borders or allocate natural resources to invest in coping strategies to climate related stress.

Emergency Management Landscape in Tribal Communities

In the area of disaster response and recovery, government has jurisdiction over tribal lands, which is often not the main point of contention in executing life saving measures during a disaster. Unlike other federal agencies whose authority often extends only to tribal lands that fit under the definition Indian country found in 18 USC 1151, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has a more expansive definition of what constitutes tribal lands.

For example, after landslides and mud slides took the lives of people in the homelands of the Wrangell Cooperative Association (WCA), a Tribal Nation located in the state of Alaska, the WCA received a presidential disaster declaration on March 15, 2024 (FEMA 2024). This disaster declaration was historic because the WCA, like many of the over 200 Tribal Nations in Alaska, does not have a reservation or large amounts of trust lands like Tribal Nations in the lower 48 states. Yet despite this, the WCA received FEMA Public Assistance, Individual Assistance, and Hazard Mitigation funding to respond to the disaster across the entire island of Wrangell. They were also able to offer assistance to their entire tribal community, which included enrolled tribal citizens and non-Natives. Showcasing that FEMA’s definition of tribal lands under the Stafford Act is flexible enough to support a Tribal Nation when responding to a disaster in their homelands, where the lands in question do not fit neatly in under the federal definition of Indian country. Meaning that FEMA can be more responsive than other federal agencies in disasters and provide Tribal Nations access to more resources and federal funding.

However, the lack of or limit of Tribal Nation civil, criminal, or regulatory jurisdiction can negatively impact efforts at mitigation, building climate resilience, as well as immediate and long-term recovery post disaster. Tribal Nations that want to build their climate resiliency often need to have jurisdiction over their natural resources to determine the best ways to conserve and effectively use those resources. Jurisdiction over tribal citizens and non-Natives is also vitally important to enforce tribal laws, regulations, codes, and ordinances to mitigate against disasters and be eligible for certain federal pre and post disaster funds.

The United States government, through legislative action and the court system, has built a legacy of transborder governance and roadblocks to disaster preparedness and recovery resources that needs to evolve for Tribal Nations to be resilient to impending disasters and the impacts of climate change. The power structure maintained through legislative action between Tribal Nations and neighboring governments needs to change for more equitable management of human and ecological systems. Tribal Nations within the same geographic frame and regional landscape have not had similar funding to neighboring and interdependent state and local governments. Tribal Nations do not have reliable and consistent annual funding to build their climate resilience and invest in emergency management capacity which has left many Tribal Nations without the necessary resources or staff to respond to disasters. The hard decisions of how to prioritize their current resources to run their governments, provide social services to their communities, strengthen their economies, and build an emergency management department are made with little to no funding.

In 2021, the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) reported that “[s]ince 2003, Congress allocated over $55 billion in homeland security grant funds to state and local governments, which averages $3.2 billion per year. In contrast, tribal nations have only been allocated just over $95 million ($5.5 million per year average) in federal homeland security funding during the same period” (NCAI 2021, 48). Tribal Nations are ineligible to receive funding directly from the FEMA via the Emergency Management Performance Grant (EMPG) program (DHS, 2023). Meanwhile, state, local governments, and territories have direct access to these EMPG funds every year, and while some states may pass through limited funding to some Tribal Nations, most Tribal Nations have no access to it.

The result of this systemic underfunding of tribal emergency management capacity means that the vast majority of Tribal Nations do not have an emergency manager, much less an emergency management program and infrastructure that can fully focus on preparing for, mitigating the effects of, and recovering from a disaster. Hundreds of Tribal Nations through tribal organizations such as NCAI and the United South and Eastern Tribes have passed resolutions highlighting the result in this vast disparity in funding and have called on the President, the Federal Administration, and Congress to provide annual consistent funding to all 574 Tribal Nations to build their emergency management capacity and capabilities (NCAI 2019; USET 2019). However, there has been no congressional movement to establish such annual funding for all Tribal Nations.

In 2018 the United States Commission on Civil Rights published a report highlighting that Tribal Nations were “particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change” (USCCR, 2018, 193). The Commission went on to note that this could be attributed to the fact that many Tribal Nations are in coastal areas, river flood plains, and in locations prone to extreme weather events. The impacts of climate change on Tribal Nations then exacerbate poor housing conditions, water quality, tribal infrastructure, access to subsistence and cultural hunting and fishing, impacts to health, general welfare, tribal economies, and more (USCCR, 2018, 193-194) Yet despite Tribal Nations being on the forefront of climate change impacts, the vast majority have not been able to access billions of dollars in funding from the Disaster Relief Fund, which is a congressional designated fund that governments can access after they receive a presidential disaster declaration.

Literature Review

Climate change will increase the number of disasters, increase severity of extreme weather, and shift where natural hazards are occurring (IPCC 2022, US Fifth National Climate Assessment 2023). With both the intensity and shifts in disasters, there is evidence communities already vulnerable by socioeconomic, political, and historic inequities will exacerbate the inequality among vulnerable communities who need to invest in adaptation planning (Birkmann et al 2022, Cappelli et al 2021, Cutter 2017). In upstate New York, in the Adirondack Region, the US Canada Border and along the Saint Lawrence River and Oklahoma, governments need to prepare for shifts due to climate change will lead to natural hazards these communities may not have yet experienced (Stevens and Lamie, 2024; Climate Institute, 2023).

With a shifting climate system due to global warming, disaster management is consequently exacerbated by the need to coordinate between a myriad of governments and in a time of increasing climate stresses (IPCC 2022). The difference for decision-makers in Tribal Nations is these leaders must also wrestle with the added challenge of advocating for equitable and adaptive policies with an international border that is treated differently than other national boundaries (Warner 2015). Investing in building a more resilient community must include leadership development. Tribal Nations have the added burden to look for potential pathways through the network of governments for mitigation investments and to build their adaptive capacity and resilience (Tsosie 2019).

Adaptive capacity is most simply the ability to adapt. However, when discussing the capacity of communities to adapt to the risks and hazards of climate change, it becomes much more complicated (Adger 2006, Engle 2011, Siders 2019, Smit and Wandle 2006, Yohe and Tol 2002). International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is a global effort through the United Nations to understand the science of our ecological system, how climate change will impact it, and what is the global policy needed to build resilience of communities on local to international scale. The IPCC produces updated series of reports sharing and framing science knowledge intended to inform policy on global scales. In conversational about international borders, it is helpful to have shared goals and definitions for the challenges climate change poses to international boundaries. According to IPCC (2022) the community’s adaptive capacity is being able to adjust to climate by taking advantage of opportunities coping with the consequences and resilience is expanding their capacity to cope with a hazard then maintain their essential function, identity and structure and persist while maintaining that adaptive capacity. Looking at building partnerships to expand the capacity of communities to adapt and build resilient requires building partnerships, and if there is a history of mistrust with regional governments or anchor institutions that is critical and challenging to overcome (Brenner 2023). Understanding the risk communities face is a confluence of their exposure to a hazard, how vulnerable cohorts within the community are, and pressure climate change is exacerbating on the couple human and natural systems (IPCC 2019). Comprehending the vulnerabilities within a community and potential adaptive capacity is not just exposure to a hazard but also in sensitivity and resilience of the coupled human and environment system to respond and adapt. Reducing vulnerability and building resilience and adaptive capacity is the key to managing risk.

There is a lack of emergency management literature or research focused on Tribal Nations when compared to other areas of research in the field. However, much like Tribal Nations, this research and literature is incredibly important and necessary to overcoming the gaps in disaster preparedness, response, and recovery efforts across the globe (Greten and Abbott 2016, Nursey-Bray et al 2022, Tsosie 2019, Warner 2015). There are comparative case studies in other locations that can contribute to understanding the challenges and hurdles that Tribal Nations in certain regions face, however as discussed, each Tribal Nation has its own history, governance system, and specific challenges to consider as well (Luft 2016, Montesanti et al 2019, Sunshine et al. 2015).

Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe

The Kanienʼkehá꞉ka (or Mohawks as they are known in English) have managed to preserve, maintain, and foster a unique culture for thousands of years. The Mohawks of Akwesasne are descended from the “keepers of the eastern door” of the Six Nations Iroquois or Haudenosaunee Confederacy. Their traditional territory includes the north-eastern region of New York State extending into Vermont and southern Canada. The name Akwesasne applies to the entirety of the community. Politically, the Mohawks on the United States portion of Akwesasne had dealings with colonial representatives and later with governments of the State of New York and the then newly founded United States federal government. The history of the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribal government reaches back to shortly after the American Revolutionary War and has continued with the selection of representatives in 1898-99, responding to the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of the 1930s and legislative termination efforts in the 1950s and becoming a federally recognized tribe in 1973.

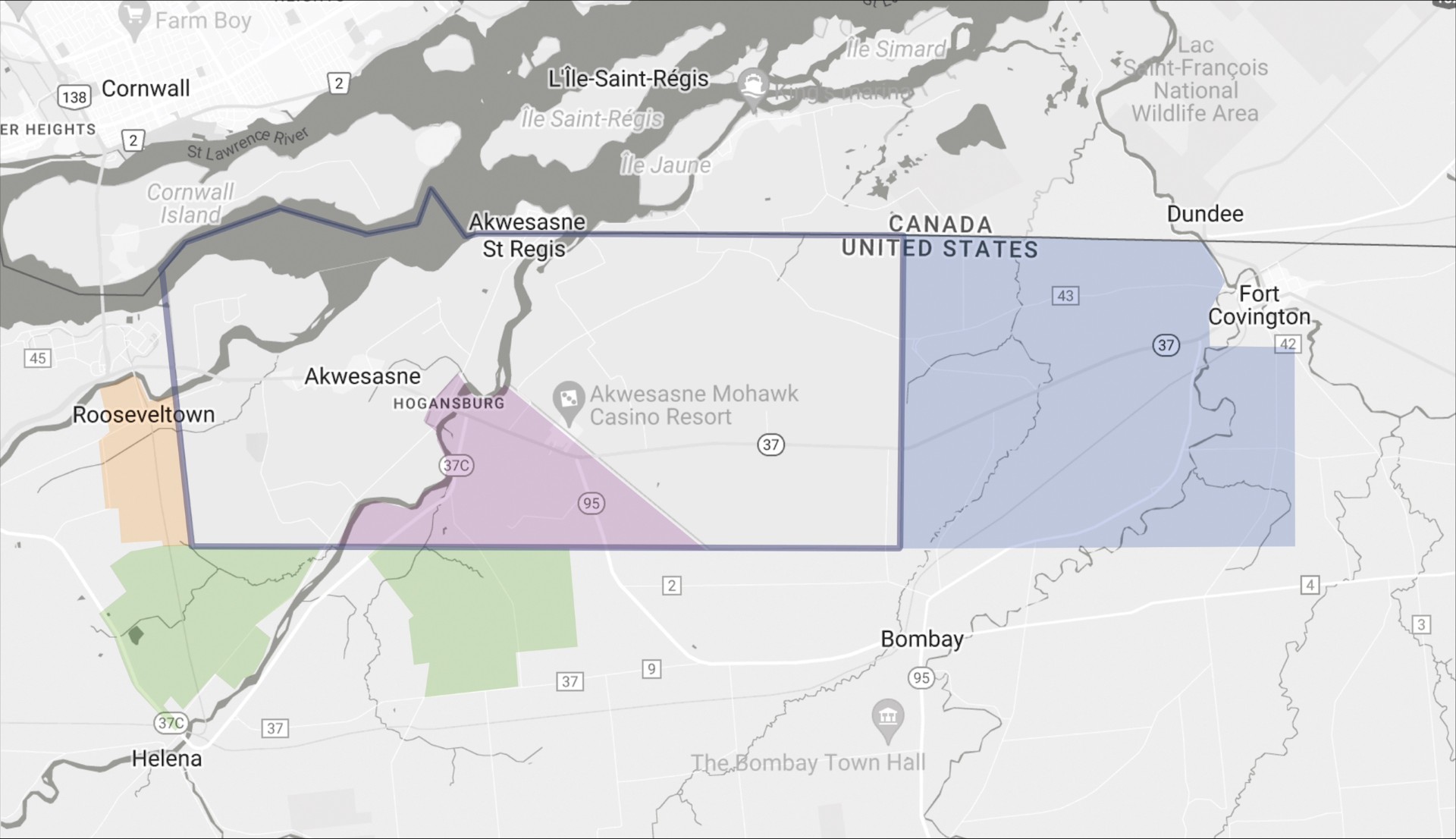

The Akwesasne Mohawk reservation spans two countries, the United States and Canada, and is adjacent to different provinces and local counties within those two countries, as demonstrated in Figure 1 below. The Akwesasne community consists of approximately 19,000 acres of wetland, agriculture lands, woodland, and light commercial development. The median household income is $32,050 and three rivers (St. Lawrence, St. Regis, and Racquette) run through the reservation. The Mohawk Council of Akwesasne governs the northern portion of the territory neighboring the Canadian jurisdictions. The southern portion is governed by the Saint Regis Mohawk tribal government. The reservation spans approximately 29.7 square miles and 7,741 tribal members reside within the borders of Akwesasne.

Today, the Saint Regis Mohawk tribal government consists of a Tribal Council that includes three Tribal Chiefs and three Sub-Chiefs who are elected officials. They each serve three-year staggered terms. The Tribal Council possesses legislative and executive governmental authority. The judicial authority is vested in the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribal Courts. The Tribal Courts consist of a trial, appellate, and traffic court. The trial level is led by an elected Chief Judge and the appellate court consists of an appointed Chief Appellate Judge and Associate Appellate Judges. The traffic court consists of two elected judges. Each elected and appointed judge serves a three-year term. The record keeping and recording authority is vested to an elected Tribal Clerk. The Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe administers its own environmental, social, policing, economic, health, emergency response teams, and educational programs, policies, laws, and regulations. The administrative work is done by designated tribal divisions overseen by the Tribe’s Executive Director.

The Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe has an Environmental Division and Office of Emergency Management and Safety that is responsible for addressing the challenges brought about by climate change and responding to emergencies (St. Regis Mohawk Tribe, 2024). The Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe also has a tribal police force, and the Tribe has active volunteer fire departments on both the northern and southern side of the Akwesasne Mohawk reservation. The northern portion of the territory governed by the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne has equal counterparts such as an Emergency Planning Office, Akwesasne Mohawk Police, and a volunteer fire department. During his interview, Nolan Jacobs, Division Director, Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe Office of Emergency Management and Safety (Jacobs 2024) explained that the two tribal governments work together but are forced to operate under their separate umbrellas of authority due to funding limitations because funding from the federal government cannot be used to fund tribal programs and divisions on the northern side of the territory. However, his interview demonstrates how the tribal governments work together in emergency situations. The emergency teams within the tribal governments navigate power outages together and recently coordinated planning involving the solar eclipse.

Like other Tribal Nations, the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe is experiencing challenges with its members’ health and climate change. Before the 1950s, the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe had rare diabetes occurrences, but currently in Akwesasne, there is a high level of cancer, diabetes and other health-related diseases. During the COVID-19 health pandemic, tribal communities were at high risk due to the overall health of its members. The Akwesasne landscape is unique with its available water resources such as the St. Lawrence River that is a vital resource to the Akwesasne Mohawks. The territory has contaminated rivers, fish and wildlife caused by the industrial plants upstream from Akwesasne for decades.

Climate change, including long-term changes in weather patterns caused by anthropogenic emissions, poses an additional threat that is exacerbated by these health challenges. There is already an increased frequency in Akwesasne in extreme weather events. The drought of 2012 in Akwesasne “affected many of nature’s cycles on all of creation” (St. Regis Mohawk Tribe, 2013). The changes came about in the way of hot and humid temperature, high winds, and low water levels. An issue that the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe is faced with is ice jams, an accumulation of ice that acts as a natural dam and restricts the flow of a body of water. This can lead to flooding which impacts community members and nearby towns.

The Saint Regis Mohawk tribal lands is also located along the Saint Lawrence River that is highly vulnerable to sea level rise (BCA Architects & Engineers and Rootz, LLC 2019). As the Tribal Nation’s territory sits along the Saint Lawrence River, to respond to a disaster they need to rely on crossing international and potentially conflicting political borders. As indicated by the Director of the Office of Emergency Management and Safety, the border creates challenges because each tribal government receives some funding that cannot be used on the other portion of the territory. Further complicating the management of that international boundary is concerns of illegal border crossing between United States and Canada. The Saint Regis Mohawk Tribal Police are involved with efforts to secure the border with local and national partners. The common hazards the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe experienced are floods and ice jams, but winter storms, landslides, fires, droughts, and extreme heat have impacted the region too. In addition to these disasters, there are hazardous waste sites managed by the United States Environmental Protection Agency that can impact the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe. In recognition of their shared interests and unique jurisdictions, in 2020 the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe and the State of New York entered into a historic cooperative agreement to accelerate the restoration of natural resources, cultural resources, and traditional Native American uses along the Saint Lawrence River Area of Concern, which includes the polluted area of the river. (Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe. January 22, 2020. “DEC and SRMT Announce…”).

Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma

The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma and its tribal citizens were removed from their traditional homelands across the modern-day Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. The Nation was forcibly relocated by the federal government on the Trail of Tears starting in 1831 to modern day Oklahoma. They are the proud descendants of the Nations that built Moundville, the second largest settlement north of Mexico, a center of excellence in arts, agriculture, spiritual growth, trade and more, which existed around 1250 AD, located along present-day Tuscaloosa County Alabama (“Ancestors” 2015; Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma “Cultural Services” n.d.). The Nation has a rich culture, language, and history, which are prioritized by leadership.

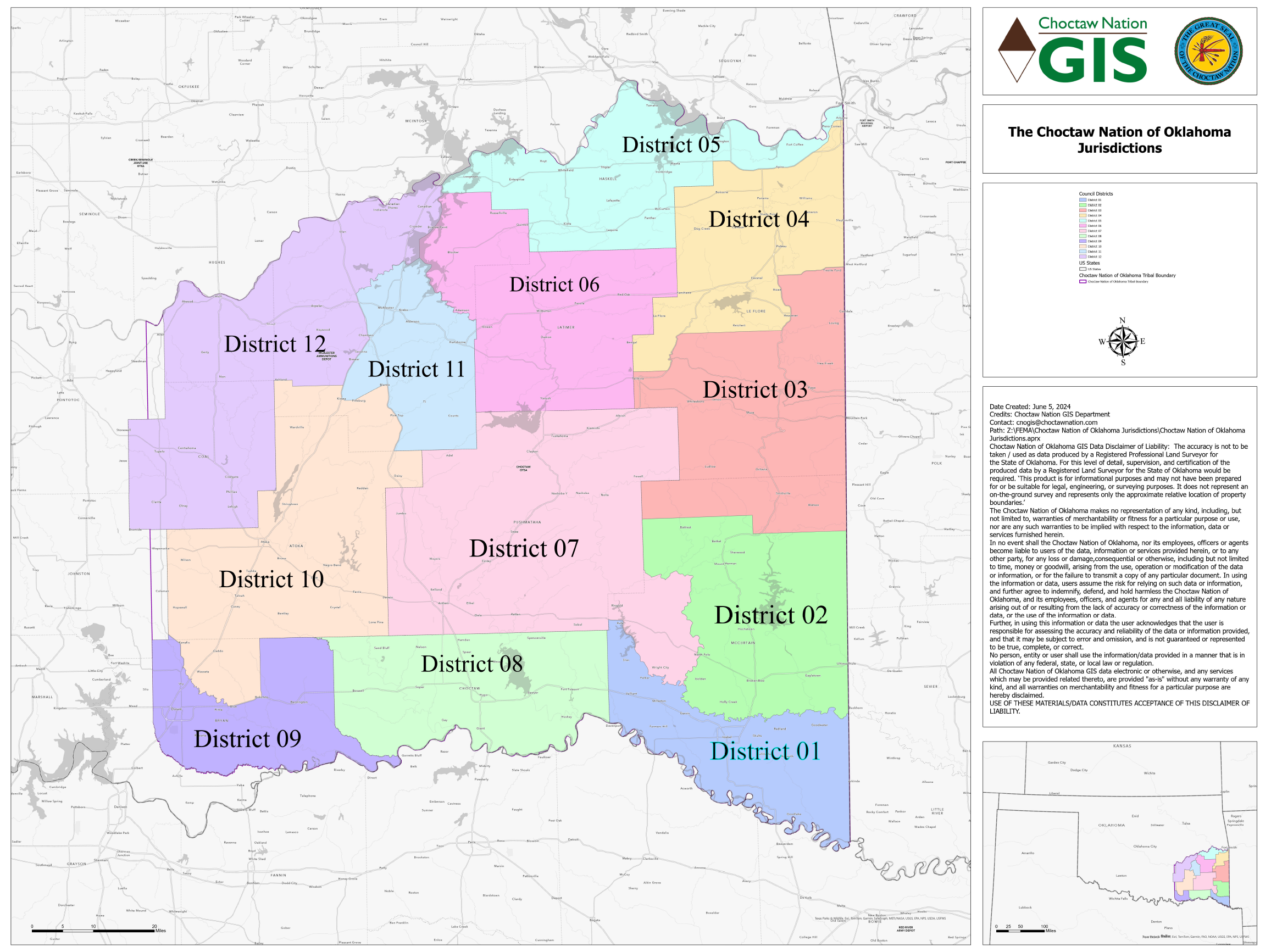

The Choctaw Nation’s reservation includes 11,000 square miles and thirteen counties in the southeastern portion of Oklahoma (Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma “Choctaw Nation Reservation” n.d.). This means that the Choctaw Nation must work with the State of Oklahoma, eleven counties and hundreds of local governments that are within their reservation boundaries. The Choctaw Nation is the third largest Tribal Nation in the United State with a significant land base and over 225,000 enrolled tribal members (Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma “About the Choctaw Nation” n.d.).

The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma government is divided into three branches of government with an executive branch lead by a Chief and Assistant Chief, a legislative branch led by a twelve-member tribal council, and a judicial branch. (Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma “Choctaw Nation Government” n.d.). The Choctaw Nation employs over 10,000 people and operates several businesses including three casinos, resorts, gas stations, restaurants, and farming operations. The Choctaw Nation also owns and operates health care, manufacturing, and recycling facilities. In 2018 the Nation had a $2.7 billion dollar impact on the economy.

Oklahoma is home to thirty-nine different Tribal Nations, with some whose homelands are originally in the state and many who were moved there by the federal government as part of Indian removal era. Across several Tribal Nations located in Oklahoma, the climate crisis is causing extreme weather, wildfires, and drought. Those disasters do not stop at tribal lands and managing these events often cross several jurisdictions and regional landscapes.

Tribal Nations as sovereign nations are no stranger to relationships with nations outside of the United States. Tribal Nations have also been practicing climate resilience and emergency management well before there were terms for either practice. A great example of both can be seen in the relationship between the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma and the Republic of Ireland, which has endured for almost two hundred years. A few years after the Choctaw Nation was forcibly removed to Indian Territory (modern day Oklahoma), the Choctaw people heard of the Irish who were dying due to starvation or malnutrition in their homelands. Choctaw tribal citizens then went across the reservation to raise money and in 1948 the Choctaw Nation sent $500 or $5,000 in today’s money to aid the Irish and save lives. The result of the Choctaw Nation’s act of kindness, international aid, and emergency response created a bond between the two Nations that has lasted to today (Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. “Choctaw and Irish History.” n.d.). In recognition of the Choctaw gift, in 2020 many Irish citizens donated funding to help the Hopi Tribe and the Navajo Nation during the height of the pandemic. The Choctaw Nation and the Republic of Ireland regularly keep in contact, share culture, leadership visits, and there is a monument to the Choctaw gift in Ireland with a sister monument being built on the Choctaw reservation today.

COVID-19 was an important example of how different actors, including different governments, Tribal Nations, and anchor institutions could form partnerships to manage disaster across borders (Brenner, Eiseman, and Dunn 2024). Despite the lack of access to direct disaster funding during the COVID-19 pandemic, and lack of capacity building funding from the federal government for decades, many Tribal Nations went out of their way to support entire communities during the pandemic. Examples of this can be seen in many Tribal Nations that opened up their vaccine sites to all people including non-Natives (Citizen Potawatomi Nation May 10, 2021). In many places Tribal Nations were seen as the trusted government source for COVID-19 response and vaccine information. For example, April Sells, the Director of Tribal Emergency Services for the Poarch Band of Creek Indians, reported that her Nation had several non-Native individuals from outside of their tribal lands travel to their Nation to receive their COVID-19 vaccine (Sells 2023). Those individuals shared with the tribal staff that they trusted the Tribal Nation more than the federal, state, or local Government and would get the vaccine only from the Tribal Nation. The Poarch Band of Creek Indians also kept ambulances on hand in case anyone had a bad reaction to the vaccine, which increased the trust of those who were seeking a vaccine. The result of this trust with the Poarch Band of Creek Indians and other Tribal Nations led to more people both inside and outside of tribal lands getting vaccinated. During the pandemic Tribal Nations also offered food and clothing assistance as well as other support programs to both tribal citizens and non-Natives in their community to offset the impacts of the pandemic (Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma “Programs and Services” n.d.). “Yes, I do want to protect my own people, but it’s important that we protect each other” shared Amber Gammon, Continuity of Operations Program Manager for the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. The Citizen Potawatomi Nation located in Oklahoma, who before the pandemic acquired some of the only ultra-cold storage units in the state, stored many of the state’s vaccines along with the Nations vaccines in their facilities, and helped to distribute those vaccines (Citizen Potawatomi Nation Feb. 4, 2021).

While there are so many Tribal Nation success stories throughout the pandemic, it is important to recognize how Tribal Nations could be even more successful if they had the necessary support and funding needed to build their emergency management response capabilities beforehand. The same is also true for Tribal Nation success stories that emerge from other disasters. The more supported and prepared a Tribal Nation is before a disaster strikes, the better off the entire community is during the response and recovery phase.

Methodology

To best understand and invest in replicable consistencies to empower international and local leaders to work together to build disaster resilience, we must first explore how disasters are currently managed and what is needed to build resiliency within these Tribal Nations. Climate change will increase pressure on Tribal Nations to coordinate more internally and to plan externally with neighboring local, state, and federal governments. To better comprehend challenges faced in decision-making and how to invest in adaptive capacity a series of interviews were conducted with Tribal Nations emergency management leaders within the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe and Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. This process and questions were reviewed by Cornell University’s Institutional Review Board to ensure fair and unbiased responses.

To conduct the survey in a safe and equitable space, four interviews were conducted by and/or directly with enrolled tribal members of the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe, Te-Moak Tribe of Western Shoshone, and Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. Having the interviews be conducted by trusted members from within the community was important to ensure that the interviewees who were asked to discuss potential vulnerabilities of their emergency management system felt and maintained safety and security. Interviewees were selected exclusively from within the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe and Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma leadership team to better understand the challenges they face in decision-making, planning, and building adaptive capacity. Participants had to be a part of the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe and Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma communities. The plan was for decision-makers within these Tribal Nations to have conversations and be asked survey questions. The goal was to understand the challenges and implications these tribal communities face for disaster management given the international borders between these Tribal Nations and with the United States. As these are historically vulnerable communities, the most important driver in developing interview logistics was protecting and respecting the space and leadership and of vulnerable community members in how their information would be used and who was involved. While it is interesting to learn about what kind disasters these communities are facing, that was not the focus and intent of the interview; whatever the disaster, the goal of these interviews was to understand the policy and institutional structural challenges these communities face.

Only tribal citizens that could speak on behalf of the Saint Regis Mohawk and Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma leadership teams and departments were interviewed. There were eight open-ended questions, and each interview was anticipated to take thirty minutes. It was made clear to participants that participation in this study and responding to each question was completely voluntary. Participants were provided multiple ways to contribute and could elect to communicate their responses in one of three ways. The first option was as a one-on-one conversation on Zoom or via phone with audio recording only, the second option was as an in-person conversation with audio recording, and the third option was to email typed or written responses to the questions. All participants were asked the same eight questions. Participants were given the option not to answer any of these questions. Audio recordings were only used to confirm responses and there were no video recordings. The following are the eight questions all participants were asked:

- Do you consent to this interview?

- Can you state your name and tribal affiliation?

- What is your role within the tribe?

- How is emergency response managed within your tribe?

- How often is it updated and how?

- Are updates coordinated across international and other municipal boundaries?

- What are challenges for a changing climate for communities to manage international border resources?

- Is there anything you would like to add that was not asked about challenges disaster management across boundaries?

Findings and Solutions

In 2013, the Robert T. Stafford and Education Assistance Act (Stafford Act) was amended by Congress to allow Tribal Nations to choose to go directly to the President to request a federal disaster declaration to access Public Assistance, Individual Assistance, and/or Hazard Mitigation funding from the Disaster Relief Fund. Even though this pathway has been open to Tribal Nations for over a decade, there have been less than 30 tribal major disaster declarations to access the funding (FEMA, n.d., “Disasters and Other Declarations”). During the same time there have been over 13,000 federal disaster declarations declared by state and territorial governments (FEMA, n.d., “Disasters and Other Declarations”). For the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, when every state and territory were granted a major disaster declaration, only three Tribal Nations were able to declare major disaster declarations to directly access various disaster funds set aside for presidential disasters related to the pandemic. Many Tribal Nations and Tribal Organizations have cited the lack of funding for tribal emergency management programs along with administrative burdens such as a high damage threshold and non-federal cost shares as the reasons for the lack of tribal access to direct disaster declarations (Allis et al., 2020; Allis et al., 2020).

To best manage disasters, Tribal Nations must develop modern responses to emergency management within their boundaries. Even if a Tribal Nation does not have an emergency manager or emergency management program, when disaster strikes, someone within the Nation is appointed to take over the responsibilities of an emergency manager in addition to their current role within the Nation. This can range from the chief executive of the Tribal Nation, such as the Chairwoman, President, Chief, or Governor to heads of departments such as the Chief of Police, Fire Chief, Director of Healthcare or any other staff of the Nation. This person will then take on the responsibility learning about the highly complex FEMA process to access federal resources to help their tribal community members and work with FEMA staff and leadership to execute necessary administrative steps if possible. Many current Tribal Nation emergency management positions or programs were developed after a significant disaster impacted the Nation and devastated the community.

Some Tribal Nations have several multi-jurisdictional agreements either written or verbal with neighboring jurisdictions including local governments, states, and fellow Tribal Nations. These agreements can range from criminal and civil jurisdictional issues to emergency management support. Tribal Nations throughout Indian Country have repeatedly demonstrated that when a disaster strikes, they are focused on saving anyone in the jurisdiction, not only those who are enrolled within a Tribal Nation (Allis et al., 2020; Allis et al., 2020). A great example of this can be found in the 2023 tornadoes that struck Shawnee Oklahoma, where five Tribal Nations deployed to assist tribal, State, and local emergency management efforts to save lives (Gables 2023; Citizen Potawatomi Nation 2023). The Citizen Potawatomi Nation, whose headquarters is located in Shawnee, Oklahoma, opened up their two-story tornado shelter, which is attached to their casino, to all tribal community members, which included both Native and non-Native members, during the storm, saving lives (Gables 2023; Citizen Potawatomi Nation 2023).

Some Tribal Nations, in an effort to increase inter-tribal coordination and share knowledge and resources have created inter-tribal emergency management coalitions or organizations (Inter-Tribal Emergency Management Coalition, n.d.; Northwest Tribal Emergency Management Council, n.d.). These coalitions of Tribal Nations serve as a way for Nations to build their emergency management capacity and knowledge amongst each other by sharing best practices and materials (Inter-Tribal Emergency Management Coalition, n.d.; Northwest Tribal Emergency Management Council, n.d.). They also serve as a way for Tribal Nations to communicate and coordinate resources during and after disasters happen within or next to any of their jurisdictions. Some Tribal Emergency Management coalitions also work to improve local and national emergency management policies and programs by advocating Congressional changes and actively engaging in various FEMA tribal consultations or through members who serve on FEMA advisory committees (FEMA, n.d., “National Advisory Council Members”; FEMA 2023).

Tribal Nations across the United States have continued to build resilience and respond to disasters as best as they can when the situations arise, despite the lack of funding for capacity building that is desperately needed to sustain their programs. This is because emergency management and disaster resilience are not something that is new to Tribal Nations, who were practicing both well before the United States became a country. This can be seen through various forms of traditional ecological knowledge practices to stave off disasters, such as controlled burns, planting rotations, or various uses of nature-based solutions. In recent years, the Biden-Harris administration and FEMA have supported Tribal Nations traditional ecological knowledge and nature-based solutions to combat climate change (FEMA 2022; White House Nov. 30, 2022; White House Dec. 1, 2022). While these federal policy changes have been helpful in supporting tribal sovereignty and self-determination, they need to be followed by proactive funding effort to ensure that all Tribal Nations are able to build and sustain their own emergency management programs.

Part of the interviews explored the history and background of the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe and the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. These interviews laid a foundation for the partnerships and relationships that disaster planning can build upon.

Key Challenges and Recommendations for More Effective Emergency Management

The interviews continued to draw on understanding current management practices and challenges to better prepare for growing risk of climate impacts. The interviews explored that it is critical to invest in building equitable relationships with Tribal Nations and engage tribal communities to be part of developing policies, processes, and pathways that reduce vulnerability and exposure to climate risk. As interviews continued, Tribal Nation members shared during various consultations with the federal government, building relationships before disasters is paramount to ensuring effective communication and coordination of resources between jurisdictions. This means that jurisdictions will need to be proactive in building sustainable relationships with Tribal Nations before a disaster is even on the horizon. Further, this is reinforced in literature that social protections are a key part disaster risk management (World Risk Report, n.d.).

Understanding the historical relationship between the Tribal Nation and the relationship between the government or organization has had with the Nation in the past needs to be understood and acknowledged to grow the partnership. The previous actions of any government or organization will proceed conversations and intent, and efforts must be made to actively and overtly recognize and acknowledge to work together knowing that history has permanence. For local, regional, state, federal, or international governments to collaborate effectively with Tribal Nations, it is important for those governments to take time to invest in understanding the government framework of that specific Tribal Nation. The burden of understanding governance structures should not solely fall on the Tribal Nations, even though historically it has. Before engaging with a Tribal Nation, non-tribal governments and their staff should listen, review cultural and historic resources that the Tribal Nation themselves presents, and conduct substantial research before reaching out to the Nation to demonstrate respect. Also, it is critical to understand how each Tribal Nation separately governs, identifies, and sets priorities to avoid inadvertently offending the Nation’s staff and leadership. These partnerships need to be more of a mutual understanding and collaboration rather than one government with the responsibility to adapt to the other.

Based on the interviews and building off historical implications, there are four key areas to invest in and build on through policy and legislative actions. These four recommendations can drive the change needed to invest in the adaptive capacity needed for Tribal Nations to build resilience.

- Recommendation 1: Funding—Establish Annual Consistent Funding for All Tribal Nation Emergency Management Programs. Unless there is funding to ensure that all Tribal Nations can hire full time emergency management staff to build their baseline capacity, it will be almost impossible to build sustainable climate resilience, and coordinate disaster response across Indian Country.

- Recommendation 2: Jurisdiction—Reaffirm Tribal Nation Civil, Criminal, and Regulatory Jurisdiction Over their Lands and Everyone Inside of their Jurisdiction. Tribal Nations must contend with over two centuries of Federal Indian Law Jurisprudence. Reaffirming tribal civil, criminal, and regulatory jurisdiction over their lands and everyone inside of their lands will remove several coordination and resources roadblocks that exist today.

- Recommendation 3: Education—Require Education and Trainings on Tribal Jurisdiction, Tribal History, Sovereignty and Self-Determination. Working with Tribal Nations is incredibly complex and rewarding. The first step that any government or jurisdiction needs to take when wanting to support and work with Tribal Nations is to learn. Learn about the general information and complexities that impact all Tribal Nations and learn about the specific histories and challenges that impact the Nation you are planning to work with going forward. If you show up already having done your homework, you will be leagues ahead of other jurisdictions. This training and education must be required for all Federal Emergency Management Agency staff because their work will at some point overlap with Tribal Nations or tribal citizens.

- Recommendation 4: Coordination—Overcoming Political Pitfalls Between Levels of Governments. Tribal Nations have their own governance but have interdependent relationships with supporting federal, state, and local jurisdictions. Each of these relationships are different and there is a lack of consistency in managing partnerships based on varying governance structure within Tribal Nations and levels of trust and collaboration with external governments. However, deliberately prioritizing meaningful inclusion when building adaptive policies that include and recognize the Tribal Nation’s role will build climate resiliency for all.

Discussion of Implications

These interviews resulted in four key recommendations, which are funding, jurisdiction, education, and coordination. These four recommendations are intended to inform decision-makers with needed changes to build resiliency for Tribal Nations and neighboring governments. Translating these recommendations into action creates implications to improve the adaptive capacity and build resilience of these Tribal Nations.

Funding

There is a distinct and notable need for resources to build Tribal Nation’s emergency management capacity. Although there is interdependence with federal, state, and local governments for disaster response and recovery, there is no consistent annual funding for all Tribal Nations to build their emergency management departments like there is for state and territorial governments. States are not required to pass through EMPG funding to Tribal Nations and as a result it forces Tribal Nations to rely on the discretion of a sovereign that they may not have a treaty or trust relationship with, to access these federal resources. The result is that tribal emergency management capacity is vastly underfunded, leaving Nations vulnerable to climate change and disasters.

One interviewee explained this challenge through staff investments in Choctaw Nation. The Choctaw Nation has invested in their community protection capabilities, which includes the Department of Emergency Management, Department of Criminal Justice, and Office of the Fire Marshall. However, the Nation could still use more staff in each department to fully support preparing for, responding to, and recovering from disasters inside of their reservation. Regional local governments regularly rely on the Choctaw Nation for support for emergency management, so the Nation is not only supporting tribal citizens but the hundreds of jurisdictions across and adjacent to their reservation.

In addition to the Choctaw Nation lacking the consistent funding needed to build climate resilience cross their reservation, another interviewee also shared another challenge is that local jurisdictions also do not have resources for their own emergency management teams. This means that these local governments must rely even more on the adjacent Tribal Nation to help support their response and recovery efforts as well as building climate resilience. This has grown incredibly hard as drought continues to plague the Choctaw reservation, and with the climate becoming more arid, the way of life on the reservation will have to change to adapt to the new reality. The result is that the farming and ranching economy that both tribal citizens and non-Natives rely on, will have to change, cultural practices will have to adapt, and more preventive measures will have to be taken to stave off rampant wildfires across the reservation.

To better prepare for this, climate related disasters need to be approached with a regional lens. Funding from the US federal and state governments should be applied regionally, looking first at the ecological system, and using that system’s boundaries and impacts to drive funding pathways. In this way, there can be collaboration to build and invest more efficiently in disaster mitigation for both Tribal Nations and regional jurisdictions, being able to prepare and share resources more efficiently.

Jurisdiction

In discussions about disaster mitigation investments to build response and recovery, interviewees shared that there is a distinct need to reinforce tribal jurisdiction and build a better understanding of Tribal Nation rights and cultures. The lack of understanding of Tribal Nation rights, histories, and cultures can lead to strained relationships and roadblocks to lifesaving resources. For example, shared by an interviewee was when a federal agency is not familiar with tribal rights over natural resources or jurisdictions over peoples, they cannot build programs that Tribal Nation can fully access. The National Flood Insurance Program and Flood Plain Management regulations are excellent examples of where the regulations and policies are not built to recognize the full extent of tribal sovereignty, self-determination, and the treaty and trust responsibility owed to Tribal Nations. These gaps in application create challenges in using these policies effectively in Tribal Nations. Additionally, federal agencies that do not know the long history and complexities of federal Indian law are not equipped to tackle complex tribal jurisdiction issues, especially when new case law comes down, such as with the 2020 U.S. Supreme Court case of McGirt v. Oklahoma. The case where the reservation boundaries of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation were reaffirmed and ruling then led the reaffirmation of the Choctaw Nation reservation and several other reservations, which impacts the civil, criminal, and regulatory jurisdiction within the reservation boundaries.

Plans, exercises, and relationships built either before a disaster or when communities are investing in prevention or preparedness are key to building trust that will ultimately save lives when a disaster strikes. Jeff Hansen, Senior Director of Community Protection for the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, shared that “we try to make sure that we share as much information with them [local jurisdictions] and that we gather information from them so that we have a coordinated approach to emergency management. That way we are working hand and hand with them any time we have an issue.” Jurisdictions will call the neighbors and fellow Tribal Nations that they trust first before calling the federal government. As Amber Gammon, the Continuity of Operations Program Manager for the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma shared “local people care about local people.” “The [April 2024] solar eclipse was a good example of that where we had 60-70 agencies coming together to work through that response. Local, state, tribe and Chickasaw Nation and multiple tribes, Caddo Nation and multiple counties.” Senior Director Hansen shared when explaining why building relationships and plans with your fellow jurisdictions is important. The Choctaw Nation is continuously updating their various emergency management related plans, which includes their emergency operation plan, hazard mitigation plans, continuity of operation plans, and more. They also have a deep dive refresh of their plans, set for every five years. When updating their plans, they often try to include local jurisdictions where it makes the most sense for coordination and collaboration. Senior Director Hansen noted that “each one of my emergency managers is assigned particular counties and jurisdictions as a liaison. We attend their LEPC [Local Emergency Planning Committee] meetings and provide input and coordinate with the Chickasaw Nation quite frequently. Mitigation wise we coordinate when we update our plan and meet with local jurisdictions.” The Nation will reach out to those relevant jurisdictions to collaborate and are sometimes met with enthusiasm, sometimes apathy for panning, and sometimes no response at all as the jurisdiction does not have the resources to have a staffer assigned to planning and relationship building.

The Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe’s location poses a unique challenge regarding jurisdiction. The reservation boundaries extend into two Canadian provinces and two New York State counties. The Akwesasne Mohawk are also governed by two separate tribal governments. As previously indicated, the northern portion is governed by the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne and the southern portion is governed by the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe. This can impact responses to emergencies because the Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe deals with different partners to respond. An interviewee also noted that there are challenges with funding because each tribal government receives separate funding, and it must remain separate. However, the Tribe has made relationships with local governments and the federal/crown applicable agencies to better respond to emergencies.

Education

It is critical for federal agencies and fellow governments that work with Tribal Nations to include education and training on tribal rights and the culture of the Nation they are working with on these issues. Hiring tribal citizens and those who have lived and worked in tribal lands will also help bridge this divide. With 574 Tribal Nations there are vast differences in governance structures, histories, cultures, treaties, rights, and relationships to other jurisdictions. Another interviewee explained that biggest concept to remember is that when you have worked with one Tribal Nation, you have only worked with one Tribal Nation, and cannot assume you know all Tribal Nations having only worked with one or a few. Program Manager Gammon also shared that “yes, we all have different missions, and we are all different culturally, but our job is to protect our people and to make sure that our sovereignty stays intact.” Additionally, an interviewee shared how federal agencies are required to enter into formal government-to-government consultation with Tribal Nations under Executive Order 13175 and Executive Order 14112 to gather Tribal Nation input on decisions that will impact their rights and improve pathways for resources and funding to reach Tribal Nations.

Education also opens a door to build collaborative partnerships. Learning about the past can be part of learning about mitigation and adaptation opportunities that build adaptive capacity across regional landscapes. Program Manager Gammon noted that a large challenge with her job is that “people don’t understand emergency management. So not only are we trying to do our daily jobs we are also trying to do education, education, education. People don’t understand what emergency management is or what our purpose is, even on blue sky days, making people understand that we are not in response mode, but we are still protecting our people.” Conner Hurlocker, Emergency Management Coordinator for the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma shared that he “would love to see a future where emergency management is taken more seriously, and cultural identity of tribes is taken more seriously.” Community members in Tribal Nations and non-Tribal governments have much to learn in the future disasters facing communities together.

Coordination

One of the largest challenges that all of those interviewed spoke at length about, were the political challenges to working with fellow governments. Tribal Nations must contend with multiple governments including the federal government, states, local governments, international governments, and fellow Tribal Nations. The Tribal Nation will have a long-standing history with each of these governments that will impact their view on their collaboration efforts. Each government also has complex levels of leadership that can derail the progress in relationship building between the Nation and their fellow jurisdiction. “When you are dealing with multiple jurisdictions across borders you are going to run into issues and sometimes unfortunately, they are all political.” shared Senior Director Hansen.

For example, a Tribal Nation could have strong relationships with neighboring counties, built on years of mutual respect and work, but have more challenging relationships with the State or even the reverse. In either case, the political decisions of one level of government may forestall the progress needed to ensure that everyone within tribal lands are able to receive the support and help they need when they need it most. Some interviewees noted that even the language that is acceptable to use at certain meetings spaces can make or break the relationships with certain jurisdictions. Emergency Management Coordinator, Hurlocker shared that “that I have found a good way to navigate this when you discuss climate change, you don’t say those works exactly, but instead discuss the impact of it [climate change].” With so many factors there is also the chance for misunderstandings based on misinformation, cultural differences, or lack of resources to fully support the work. Here, going back to the recommendation to invest in education helps to bridge the gap for political coordination.