9 Where Do Babies Come From?

Where do babies come from?

This may seem like a silly question but it’s fundamental to our lives. We were all born. Most people have sex during their lives. People make babies and procreate new generations to support families, perpetuate societies, and build futures. Sex, pregnancy, birth, and childcare are fundamental aspects of humanity, even though all people do not participate in all aspects. Procreation involves both women and men, although women are most associated with pregnancy, birth, breast-feeding, and childcare. Many homosexual partnerships involve parenting as well. Thus, gender is not intrinsically tied to parental roles. As discussed in the “Who Am I?” chapter, traditional gender roles often dominate in ancient and contemporary societies, though not always in the ways Europe and Euro-America considers traditional today. Oftentimes, the representation of a woman’s body with emphasized features implies procreation. Moreover, this link of an accentuated woman’s body to procreation generally symbolizes fertility, or the ability to procreate. Human fertility has and continues to be an important facet of global arts, with a linked focus to fertility of animals and the earth.

Women’s bodies

One of the most famous women in all of art history is Venus of Willendorf. You’ve seen her, right? This small limestone carving depicts a faceless woman with large breasts, a thick stomach, an exposed vulva, and weighty thighs. The Venus’ skinny arms rest atop her breasts. A sculptor living during the Upper Paleolithic period (ca. 24,000-22,000 years ago) in present-day Austria carved this representation of a woman’s body, emphasizing the areas that relate to procreation, pregnancy, birth, and childcare. This sculptor specifically chose to depersonalize this depiction, ignoring details of the woman’s specific identity. Because of this generalized and emphasized depiction of women’s procreative aspects, scholars dubbed this figure a Venus, referencing the Roman religion’s goddess of love, beauty, and motherhood. This name is anachronistic (the Roman religion developed millennia after the creation of this sculpture), but scholars use the term for interpretive meaning suggesting that this figurine represented human fertility and the importance of the woman’s body in procreation for its Paleolithic audience. This type of object, of which many are known, likely held ritual significance to its culture and may have been a burial offering.

Depictions of emphasized women’s bodies and the significance of fertility are not unique to ancient European art. For example, remember back to our discussion of Yakshas and Yakshis in the Vedic and Brahmanical traditions of ancient India in “What is Divine?” These figures are spiritual entities of nature, fertility, and abundance. Yakshi (Fig. 9.2) is much larger than the Venus of Willendorf, being created as architectural decoration for monuments at the pilgrimage site of Sanchi in India (Fig. 9.1; check out “Why Does Size Matter?” for more on Sanchi). You’ve probably noticed that despite the size difference, the yakshi sculpture reflects similar strategies of emphasis. The yakshi’s breasts, hips, and thighs are her most prominent features, as well as the adornments on her chest, waist, wrists, and ankles. While facial features were carved for this figure, they are of a general character. In contrast to the Venus of Willendorf, this symbol of women’s fertility is not in a static pose. She is actively twisting her leg around the truck of a tree and reaching up to touch the branches. Brahmanistic mythologies indicate that yakshis were fertility spirits who could make trees fruit. This power of the yakshi relates to her gender and her emphasized features associated with procreation. The fruits of women’s wombs (i.e. children) are akin to the fruits that spring from the mango tree at the yakshi’s touch.

In their unique way, the native Jōmon people of ancient Japan produced clay figurines that depict women’s bodies with emphasized features relevant to procreation. The Jōmon period spanned millennia of indigenous cultural development, prior to immigration from mainland Korea and China, and focused on the island of Hokkaido (Fig. 9.1). In 1952 CE, Japanese scholar Okamoto Tarō (trans. Reynolds 2009) began serious study of this period, described in “On Jomon Ceramics,” while most scholars still focused on developments after mainland influence.

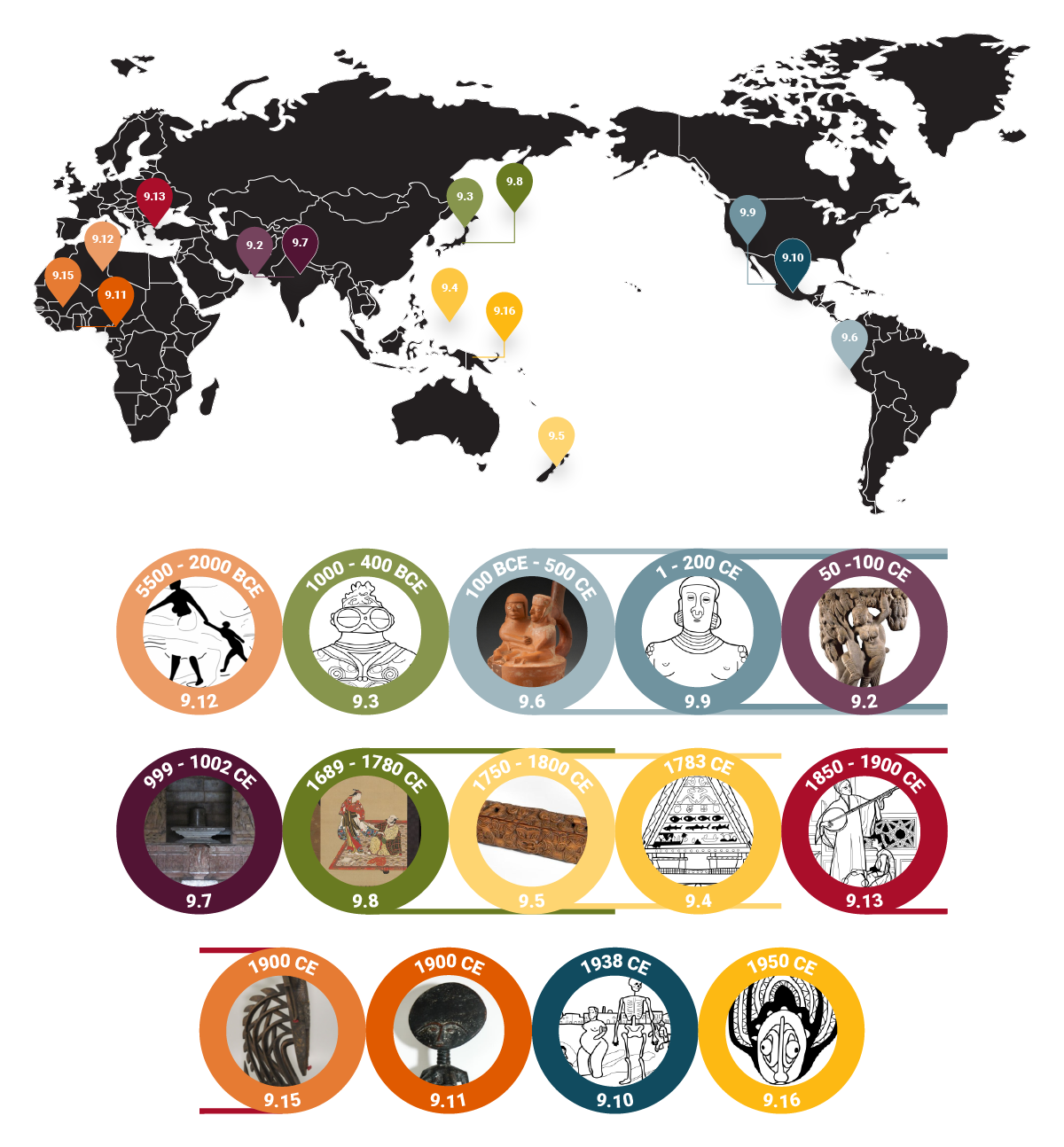

Most known for clay arts, Jōmon peoples created storage and ritual vessels with cord-marked (aka jōmon in Japanese) texture, or impressions of cord/rope into the clay surface for aesthetic appeal and functionality. Imagine how difficult carrying a large and heavy water jar a long distance with a smooth-sided clay vessel would be! That jar would definitely slide from your hands and drop on your toes. This cord-marked texture makes such vessels more functional and was used to embellish ceremonial clay figurines known as Dogū (sketched in Fig. 9.3; original here), representing a woman’s body with emphasized hips and thighs, as well as small but pointed breasts.

Another major feature of most dogū is the large stylized eyes that many scholars casually say resemble goggles or coffee beans. These figures often have elaborate headdresses or coiffures, though the dogū illustrated in Figure 9.3 has suffered some loss. Check out the original photo to see the cord-marked texture embellished decorative patterns on the figure’s torso and shoulders. These decorations probably represent tattooing or body painting practiced by Jōmon women. Swirling, tendril-like patterns encircle the figure’s breasts, accentuate the curvature and width of the hips, and cover the broad stomach and back with visual interest. ![]()

The artist that produced this figurine and the many others like it prioritized specific features of women’s bodies relevant to procreation and painstakingly applied decoration to represent the importance of this entity. Dogū demonstrated to scholars that, like many global cultures, human fertility and its relationship to women’s bodies was very significant to Jōmon people. Further, Jōmon artists produced figurines representing men later in time, possibly reflecting the development of men’s leadership roles within the society.

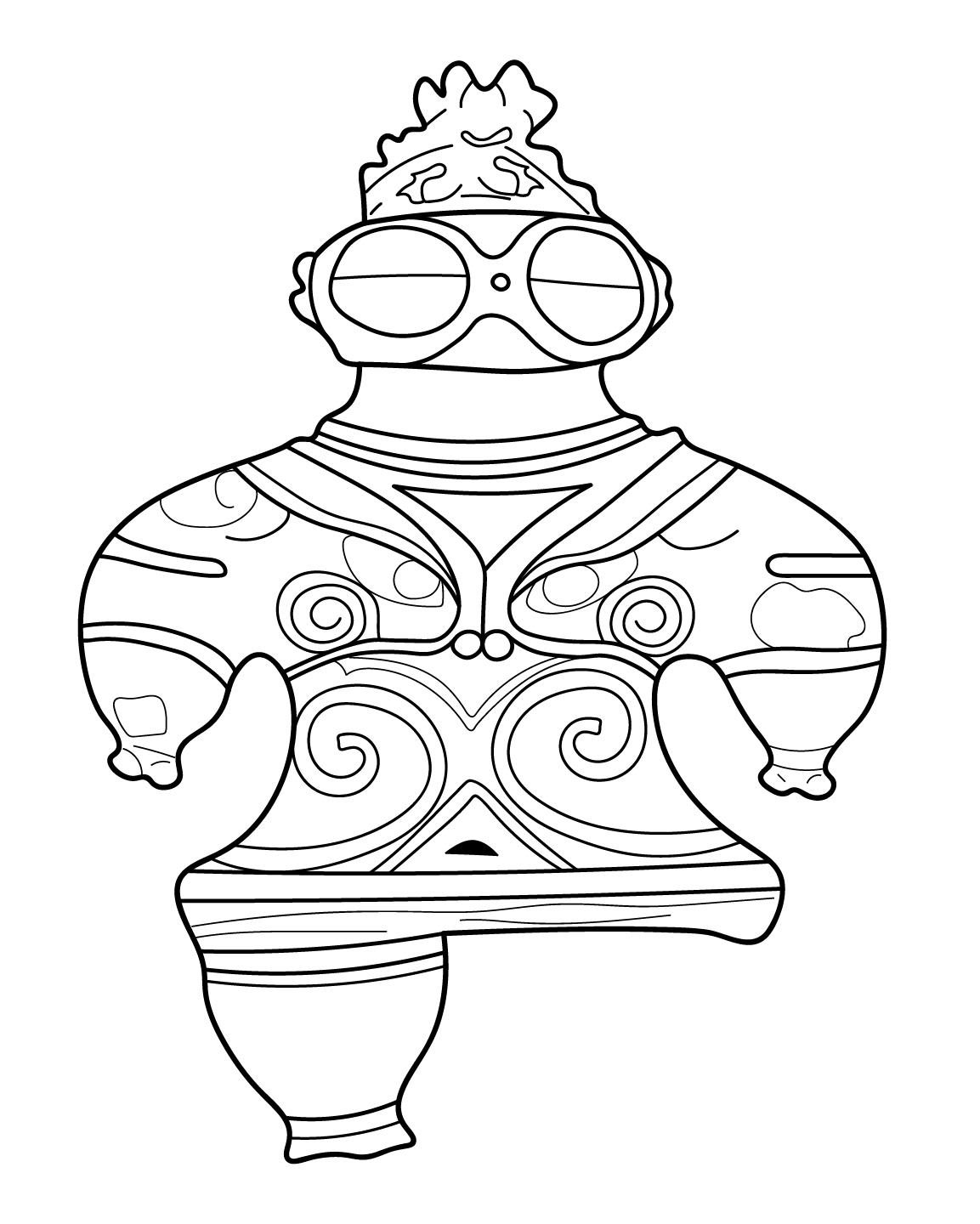

To the southeast of the Japanese archipelago, the Islands of Palau of Micronesia in the Pacific (Fig. 9.1) are home to the Palauan culture. The Palauans probably arrived in Micronesia around 1000 BCE, migrating via outrigger canoes. Over time, they developed unique traditions that place significance on women’s bodies as representations of fertility and procreation. This cultural value most often manifests as decoration on the east facade of structures the Palauans call Bai (sketched in Fig. 9.4; original here in Fig. 3). These Bai are men’s assembly halls, chiefly audience rooms, and deliberation chambers. Palauan Bai (Meeting House): Parts and Depictions as a Pictorial Representation of Palau (Tellei n.d) thoroughly details this architectural tradition.

As you walk into the Bai, your attention is drawn to the imagery above the entranceway. One recurring image is known as dilukai, the representation of a nude woman in an open-legged position with exposed vulva, typically with arms elevated above her waistline (seen in the 4th register from the top in Fig. 9.4). The dilukai’s eyes are open and very visible. She wears adornments such as armbands. In later examples, dilukai were often represented wearing skirts and thus their vulvas were not visible. These later dilukai examples are not traditional but reflect changes in Palau due to colonization. Most people agree that the original meaning of the dilukai was as a symbol of fertility, procreation, birth, and society as a whole (i.e. all the men that enter the Bai are the result of procreation, birth, and the input of women). Some also suggest that dilukai reflect the tradition of women open to sexual encounters staying in or near the Bai to find partners. Later, colonial groups referred to these women as prostitutes, but the preconceptions laden in that English term do not apply to these Palauan women. In fact, Palauan women held important prestige and power both economically and socially.

The claims of prostitution derived from Spanish missionaries, hoping to convert Palauans to Catholicism. In this process, missionaries demonized indigenous beliefs and traditions. The dilukai was a target of such demonization because this representation of women did not fit Catholic belief structures. Missionaries created new stories claiming that dilukai images represented ‘loose women’ who disrespected their families by having extra-marital sex. These fabricated legends often involved a brother creating dilukai images to shame his errant sister. These creations are examples of cultural misunderstanding, intolerance, and closed-mindedness, some of the hallmarks of colonialism. For Palauans, dilukai are representatives of fertility and the generative force of new life, a force to which we are all associated.

Depicting sex

In addition to the frequency of women’s bodies in art, there are many examples of global artworks depicting sex. A Māori artist from Aotearoa (Fig. 9.1; present-day New Zealand) carved a small wood box that served as a wakahuia (feather box) to store ornaments for special occasions (Fig. 9.5). Such boxes were repositories of spiritual power and symbols of tribal legacy in Māori culture. This box features intertwining figures with traditional stylized faces/masks, known as wheku. On the top panel, the body forms intersect as in sexual activity between women and men. This relatively abstracted representation of sex highlights the need for human fertility and abundance to ensure the survival of the Māori people. The figures probably represent the primordial parents Rangi and Papa, who through their union and fertility are the ultimate sources of life in Māori mythology. There also are examples of sexual depictions in more representational, or literal, manner.

Remember the Moche culture of northern Peru (Fig. 9.1) introduced in “Who Came Before Us?” In addition to portrait vessels of fancy rulers, Moche artists created unique painted ceramic vessels that clearly depict erotic activity and sex. For example, a Handle Spout Vessel (Fig. 9.6) depicts a couple erotically embracing, while other examples include more explicit images of sex, such as some illustrated in “Moche Sex Pots: Reproduction and Temporality in Ancient South America” (Weismantel 2004). This sculptural and painted vessel depicts two seated figures, a woman on the left and a man on the right, with their arms wrapped around each other. In this case, the woman’s body is not represented with the types of emphasis we discussed previously, but with a relatively detailed face, slightly amorphous body, and open legs revealing her vulva. The man appears to be touching her exposed vulva with his hand.

The couple is sculpted atop a squat cylindrical vessel with painted motifs. Behind the couple, the artist applied the vessel’s spout, known as a handle spout. Take a closer look at this spout. Do you think it would have been easy to use this object for pouring liquids in and out? Not really, right? These vessels were probably produced for ceremonial and/or decorative value. Many Moche vessels depict sexual activities that are not only about producing children. Thus, we should question whether the Moche were purely focused on fertility and offspring or whether these depictions of sex reflect personal pleasure and the cultural value of eroticism itself.

Let’s travel across the Pacific to South Asia to consider other examples of erotic art. At Khajuraho, India (Fig. 9.1), the rulers of the Chandela Dynasty commissioned temples with high relief exterior sculptures depicting sexual activities that also appear to relate more to pleasure than procreative needs. The Chandelas followed the Tantric movement of Bhakti Hinduism and worshiped the god Shiva (related to but distinct from the Tantric Buddhist traditions of Tibet discussed in “What is Divine?”). In Hinduism, pleasure (kama) is accepted as one goal of life, along with wealth/power (artha), duty (dharma), and release/salvation (moksha). In Tantric Hinduism practiced by the Chandelas, sex and the pleasure of sex were important facets of life, but one must not overindulge. To dive into this tradition more, check out “Secret Yantras and Erotic Display for Hindu Temples” (Rabe 2000).

Shiva is the prime example of sexual union without overindulgence, mastering one’s sexual impulses. Before Shiva was depicted in the human-like Nataraja (Fig. 4.7) and other forms, he was (and continues to be) represented as an erect linga (phallus), often in very representative forms or more abstract pillar-like forms, as in Shiva Linga (Fig. 9.7). This erect penis reflects Shiva’s status as a procreative force and his ability to sustain an erection but not give into the feeling of release. Such control and self-discipline were highly valued by the Chandela’s Tantric tradition. Thus, while pleasure is represented, there is an underlying spiritual meaning to erotic depictions within Hinduism as well. In many of the temples at Khajuraho, the Shiva linga sculpture is housed in the garbhagriha (“embryo or womb chamber”) at the center of the temple that symbolizes a womb into which Shiva procreates the cosmos.

Another dimension of sex in art is the representation of homosexuality. In many global traditions, the normalized depiction of sex occurs between women and men. In some cultures, there are additional normalized sexual relationships depicted in art. You may be aware of Greek vases representing erotic acts between men, oftentimes an older man and a younger man. Some scholars also point to images of homosexual relationships between women on Greek vessels. In the Greek context, homosexuality was accepted as part of many men’s experiences, especially with respect to their involvement in sports. In feudal and Edo period Japan (Fig. 9.1), homosexuality was an established facet of samurai culture and accepted within mainstream society. The book Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan (Leupp 1995) covers this topic in depth.

Edo period artworks such as Samurai and Wakashu (Fig. 9.8) illustrate homosexual relationships. In this hanging scroll painting on silk, the younger man on the left is looking back towards the seated older man on the right who is pulling at the younger man’s long sleeve in a seductive gesture. The ensemble worn by the younger man identifies him as a wakashu (young man) and an onnagata (actor in Kabuki theater who played women’s roles). Onnagata often engaged in sexual relationships with patrons. The older man’s hairstyle and robes identify him with the samurai class, someone of high status who would patronize Kabuki.

The setting of the painting is intimate and reflects a sexual relationship between these men. While depicted infrequently, such relationships were not taboo or illegal in Japan until recent times. One of the oldest novels in the world, The Tale of Genji, describes protagonist Prince Genji pursuing sexual relationships with both women and men. Interestingly enough, that story was written by a woman, Lady Murasaki of the Heian royal court around 1000 CE! While heterosexual unions were important for procreation and lineage sustainability, homosexuality was an appropriate form of sexual expression for Japanese men and women from many walks of life. Homosexual relationships was legally defined in Qing Dynasty China with respect to Confucian hierarchies. To explore this topic, check out Matthew H. Sommer’s (2007) “Was China Part of a Global Eighteenth-Century Homosexuality?”

Pregnancy and birth

Sex between men and women often results in pregnancy. Many women strive to be mothers from an early age and/or understand that they are expected to fulfill that role for their families. As pregnancy leads to birth, the mother and baby undergo a strenuous and taxing process. (Unfortunately, we often ignore the stress pregnancy and birth inspire in fathers.) While depictions of pregnant women are rare in the Western Canon, famous allusions to pregnancy exist, like northern Renaissance painter Jan van Eyck’s The Arnolfini Portrait. Birth is not a typical subject matter either, except as generalized décor on objects like birth trays of the Italian Renaissance, for example.

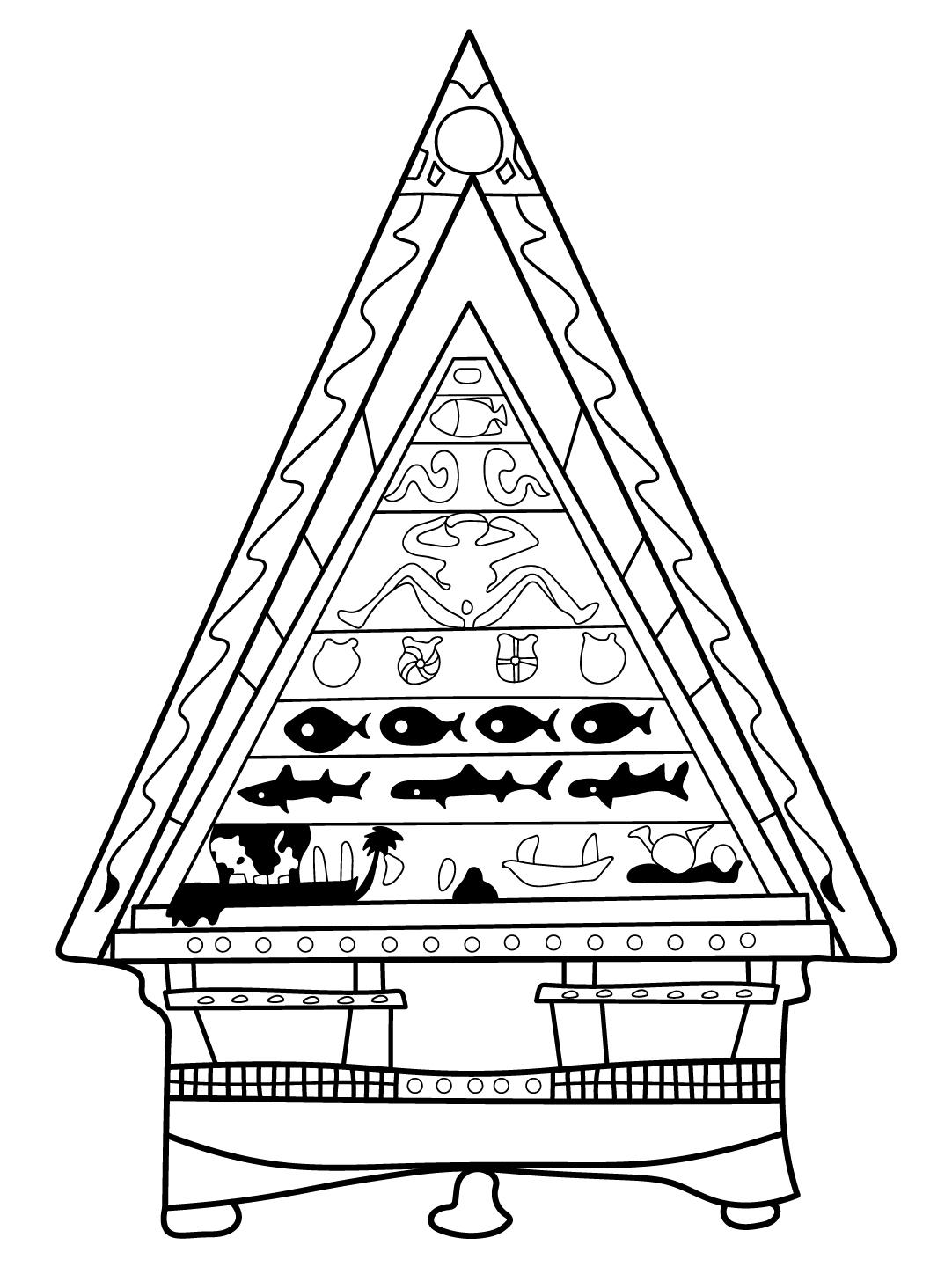

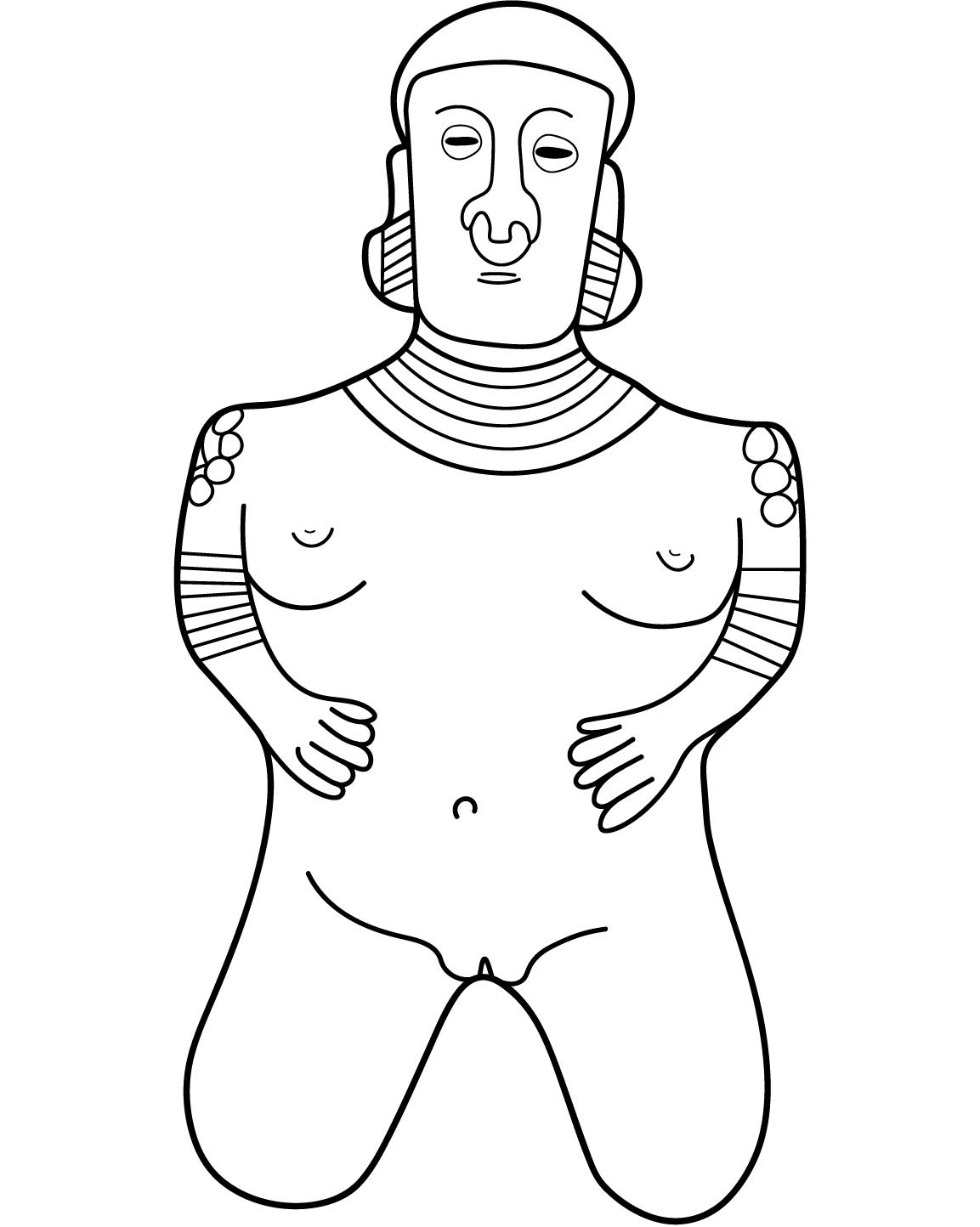

Pregnancy depictions are relatively frequent among several ancient cultures that lived along the central coastal region of west Mexico, collectively known as the Western Mexico Shaft Tomb Tradition in present-day Nayarit, Jalisco, and Colima (fig. 9.10. For example, Kneeling Pregnant Woman (sketched in Fig. 9.9; original here) derives from Nayarit and likely was provided to someone as an offering in their shaft tomb. This figure represents a high-status woman with a nose ring, large ear jewelry, necklaces, and armbands. Her breasts are swollen with milk for the forthcoming baby and her hands rest at the center of her pregnant belly. In this kneeling position, her vulva is exposed and open, possibly indicating that this woman is close to the actual process of birth. In many cultures, birthing in a lying position, like in most hospitals today, is not typical. Women often kneel, squat, or use a special birthing chair with materials beneath to protect the baby as it descends. Also, did you notice her facial expression? Her grimace may indicate that she is currently experiencing contractions and/or attempting to push. Artists of the Western Mexico Shaft Tomb Tradition didn’t just focus on imagery of pregnancy (though that was a popular theme). Check out “Archaeological Interpretations of West Mexican Ceramic Art from the Late Preclassic Period” (Day et al. 1996) to see additional ceramic examples.

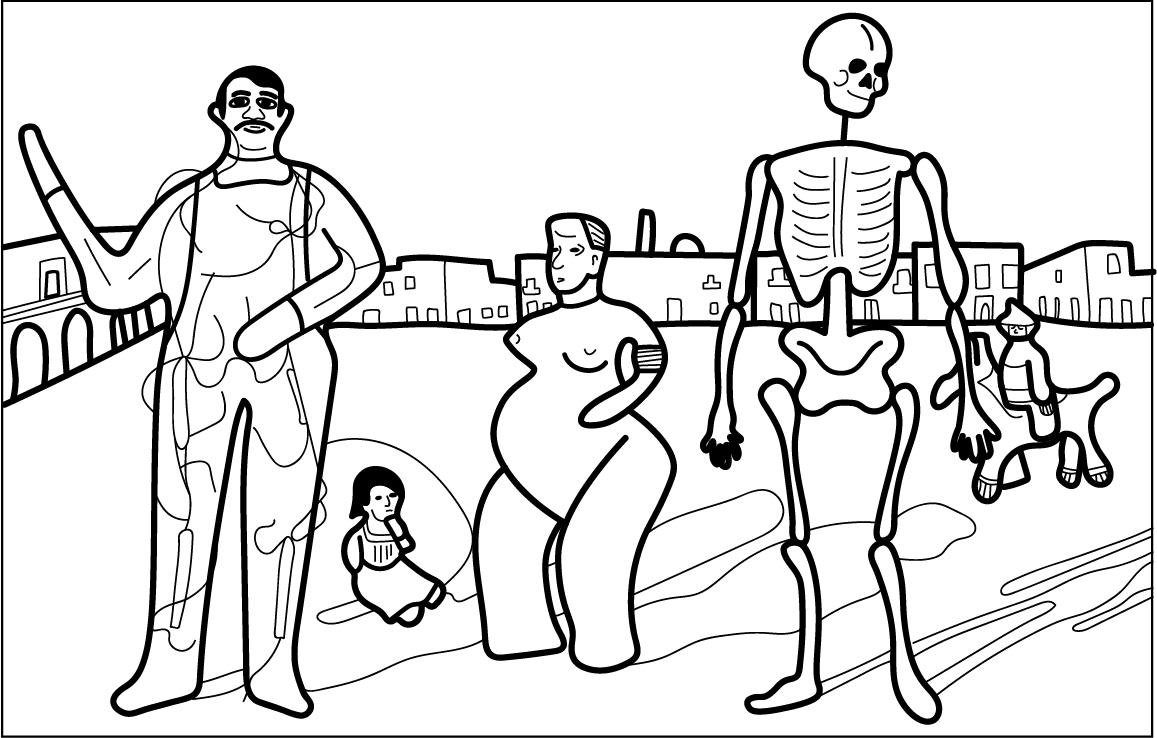

Modern Mexican artist Frida Kahlo found these ancient Mexican sculptures personally impactful. Along with her partner Diego Rivera, Kahlo invested heavily in the notion of mexicanidad (idea/feeling of being Mexican) with strong links to indigenous traditions. In addition, Kahlo held a deep-seated, though never rewarded, desire to become a mother. Have you heard the story of her accident and subsequent battles with health issues? Injuries during her youth complicated her ability to conceive and led to intense feelings of loss. She expressed these feelings in her artworks by incorporating imagery of mothers and children, breastfeeding, and pregnancy. In her 1938 CE painting Four Inhabitants of Mexico (sketched in Fig. 9.10; original here), Kahlo incorporates a depiction of a distinct Nayarit pregnant figure, in this case standing, along with a portrait of her younger self and figures illustrating change over time in Mexico.

Children and childcare

After the stresses of pregnancy abate, then comes the joy, attention, and stress of caring for children. The depiction of children in global arts is relatively rare. When seen, children often accompany a mother figure. Such mother and child scenes typically relate to the care offered by the mother to the infant. In the Western Canon, such representations often focus on religious meaning such as the relationship of Isis and Horus in Egyptian mythology or the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ in the Christian tradition, as mentioned in “Where Does Art Come From? An Introduction.” Artistic reflection upon the mother-child relationship spans human cultures, reflecting the importance of fertility, procreation, and parental care.

One important example of the prioritization of children and parental care comes from the Akan-speaking cultures, including the Asante Kingdom of present-day Ghana (Fig. 9.1). Often casually called ‘dolls,’ the Akan akua’ba tradition holds mythological significance and utmost social resonance. The mythology is focused on a woman named Akua who could not get pregnant. Childbearing is a prime expectation for Akan women. Furthermore, Akan cultures are matrilineal, prioritizing mothers in family identity and status as opposed to the prominence of fathers in patrilineal systems (dominant in Europe and European settlements). Thus, an Akan woman like Akua needs to have children to represent her family well. In the story, Akua hoped for a female child to sustain the matriline through her daughter. To ensure a good outcome for Akua’s plans to procreate, she consulted a religious specialist and received a carving representing an ideal child, later called an akua’ba based on this mythology (in the Akan language, ba means child). While many akua’ba feature a single figure, Akua’ba in Figure 9.11 represents a mother holding a child on her lap. The mother could be Akua, or her eventual daughter who will have daughters of her own.

The figure features a large round forehead and elongated neck, both features of ideal beauty and wisdom in Akan culture. This ideal child/mother is adorned with ornaments at the neck and ankles to represent status and prosperity. When Akua received her akua’ba in the story, she was tasked with treating it as a real child and carrying it on her back. This performance brought the blessing of fertility and successful birth upon Akua. Some young Akan girls receive an akua’ba to practice child rearing from a young age. This matrilineal mythology continues to impact new generations.

Most of the akua’ba surviving today date to the 1900s CE. There is a much older art tradition in Africa that reflects childcare from millennia ago. In the Sahara Desert where the borders of present-day Algeria, Libya, and Niger meet (Fig. 9.1), the caves and rocky outcrops of Tassili n’Ajjer protect over 25,000 rock paintings created as early as 7000 years ago. Rock Art of the Tassili n’Ajjer, Algeria (Coulson and Campbell 2010) illustrates the variety of art found in this region. The most famous ancient Tassili painting is known as Running Woman (fig. 9.12 left), though she is most likely dancing in a ceremony relating to fertility. A painting from the later Pastoral period (ca. 5000-2000 BCE) at Tassili depicts a bare-breasted woman tugging at a rebellious child behind her (sketched in Fig. 9.12 right; original here pg. 30). This mother and child scene probably featured in a larger painting illustrating cattle herding and semi-mobile daily life.

Figure 9.12 right: Digital Transformational Sketch by Marizela Garza of the original artwork: Pastoral Period Maker(s) of Ozaneare, Tassili n’Ajjer. Mother and Rebellious Child. ca. 5000-2000 BCE. Pigment on rock. Image source: Visona et al. 2001, 30. Refer to Figure 0.1 to view the transformational sketch process.

Pastoral period paintings at Tassili n’Ajjer reflect the cultural development of cattle domestication and agriculture in the area that we now know as one of the driest places on earth. You are probably asking yourself, don’t cows (and people for that matter) need fresh water? Yes, of course, you are right! As briefly mentioned in “Where Are We Going?”, there was much more abundant water in the Saharan region thousands of years ago. In fact, geological and archaeological investigations have shown that the environment of the ancient Sahara has cycled between desert and savanna for at least 7 million years. The people who painted Running Woman and Mother and Rebellious Child happened to live during one of the savanna environments. With reliable availability of freshwater, these people began to domesticate animals and farm crops. This lifestyle included moving seasonally with cattle herds. As Mother and Rebellious Child shows, this lifestyle also included the most human experiences we can imagine: a mother trying to get her child to move along already!

As many of you can attest, children grow so quickly! Soon, teenagers are testing boundaries and getting ready for adulthood. This sort of preparation typically occurs at home. In Muslim societies, as young girls of wealthy and high-status families grow, they live in harem (ḥarīm) spaces. The harem is not an erotic zone of forced nudity and male pleasure, but European “Orientalist” artists and writers frequently misrepresented it as such. Consider these misunderstandings more by exploring Intimate Outsiders: The Harem in Ottoman and Orientalist Art and Travel Literature (Roberts 2007).

The harem consists of spaces protected from more public areas of a family home, reserved for women and children to carry out daily activities. Ottoman painter Osman Hamdi Bey produced many works depicting harem life, often depicting daughters of the household, such as those in Two Musician Girls (sketched in Fig. 9.13; original here). On the left, a standing girl in a conservative, embroidered robe strums a Turkish tanbur while a seated girl in similar dress holds a tambourine. These girls play in a well-appointed room with painted wall tiles, carved stone balustrades, multiple woven carpets, and intricate wood paneling. Their slippers are discarded on the floor in front of them, indicating the security and familiarity of the harem space. These are not the exposed and overtly sexualized harem women of most Western Orientalist depictions.

Hamdi Bey was a bureaucrat in the Ottoman government in addition to his work as a painter, art curator, and archaeologist. He grew up in Istanbul, the capital of the Ottoman Empire (Fig. 9.1), and spent many years in France. He trained with prominent Orientalist and Romantic artists of the day, focusing on a realistic and detailed style as well as scenes of “oriental” life (a term derived from the Latin oriens, as described in “Where Does Art Comes From? An Introduction”). Unlike his French mentors, Hamdi Bey represented an ‘insider’s’ view of Muslim society and harem spaces. Most of the French Orientalist painters would not have been allowed to enter harem spaces, and thus would only have second-hand accounts or their imagination from which to develop their imagery. Erotic imagination often dictated European and Euro-American depictions of such spaces, despite the ‘insider’ images produced by artists like Hamdi Bey.

Fertility beyond humans

It will be no surprise to you that artists have represented procreation, fertility, and offspring beyond humans. We witness procreation and pregnancy in animals, such as pets or livestock, and we benefit from the fertility of the earth on our dinner plates. The importance of fertility also extends to animals and plants. Without animal procreation, would societies with large populations have enough meat to eat? Without agriculture and the propagation of plants, would large societies have enough to eat, period? Probably not. Throughout human history, there is a correlation between population growth and the development of agriculture and animal domestication. While hunting and gathering lifestyles are very successful for small groups, they cannot sustain large populations. The significance of plant, animal, and human fertility are interconnected. For humans to be fertile and produce new generations, they must have enough food. For families to maintain their agricultural and animal holdings, they need many hands to carry out the necessary work.

One example of representing the domestication of animals comes from ancient west Mexico, like Kneeling Pregnant Woman (sketched in Fig. 9.9; original here). The Colima culture lived to the south of the Nayarit culture along the Pacific coast and practiced a similar funerary tradition of shaft tombs with large amounts of offerings. The Colima tradition is known for producing ceramics with red/orange polished finishes and canine imagery. Dog (Fig. 9.14) is thought to reflect an ancient hairless breed, similar in lineage to the Chihuahua today. Most Colima dog sculptures are pot-bellied and have aggressive facial expressions. Some scholars suggest that Dog (Fig. 9.14) isn’t just rotund but also pregnant. In general, weight-bearing reflects dogs’ roles in life, likely intentionally over-fed and fattened for meat consumption. The facial expression reflects their role as protectors of the home, which is often much more aggressively taken up by female dogs (instinctually protecting a litter). These sculptures represent real-life domesticated companions and resources. Archaeology conducted to investigate Colima tombs revealed that most deceased people were provided with a ceramic dog, probably to serve as protector and guide in the afterlife.

Like humans and animals, the earth is fertile and generative. Natural productivity of the earth is harnessed and increased through agriculture. Agriculture became so important to most human societies that deities of agriculture became some of the most important spiritual entities, such as the Maize God of the Olmec from “What Is Divine?” and the Maize God of the Maya from “Will You Tell A Story?” Western traditions also value agriculture through divinities. For example, San Isidro Labrador (Saint Isidore the Farm Laborer) is the Catholic patron saint of agriculture in Spain and the Americas.

In West Africa, agriculture is crucial to livelihoods, even in the arid savanna south of the Sahara. Bamana people of present-day Mali (Fig. 9.1) have practiced agriculture since at least the 1600s CE, growing sorghum, millet, corn, and vegetables. The Bamana Ci Wara men’s society teaches young men farming skills, inspired by and named after Ci Wara, a divine being known to be half-man, half-antelope. This society performs dances with large, ornate crest masks, such the Ci Waraw (Fig. 9.15; the final ‘w’ connotes multiple, as in this pair). The masks from the UTA African Art Collection (Figs. 9.15) do not retain the original basketry at the based on the wood sculpture that would serve as the ‘hat’ to secure the crest to a performers head.

These masks feature stylized hybrid forms combining antelope horns, elongated snouts and plump bodies of aardvarks, and potentially the scaly patterning of pangolins (all native animals to the Bamana region). Chevron patterns are often carved into the curved elements of the neck (as in Fig. 9.15 left), symbolizing sun rays and the importance of the sun in agricultural productivity.

Ci Wara masks are always danced in pairs, one representing men (Fig. 9.15 left) and the other representing women (Fig. 9.15 right) with children (the smaller figure atop the larger figure’s back). The social performance recounts the story of Ci Wara teaching farming to the Bamana people, and the continuation of agricultural success among the young generations. Check out photographs of the dances performed with these headdresses in “Antelope Headdresses and Champion Farmers: Negotiating Meaning and Identity through the Bamana Ciwara Complex” (Wooten 2000). The procreative powers of the earth, animals, and humans are combined in these important ceremonies.

While the Bamana grow grains, the Abelam people of the north coast of Papua New Guinea in Melanesia 9Fig. 9.1) grow yams (known as waapi, ka, and jaambe) as their staple crop. In this tropical forest, agricultural lands are cleared by burning and then crops are carefully cultivated, primarily by men. The season of yam growing involves many taboos to ensure peaceful, successful growth. These taboos include not eating certain food, abstaining from sex, and quieting any social conflict. These behavioral controls are paramount because the yams are paramount; they embody ngwaalndu or ancestral spirits linked to each farmer and his family.

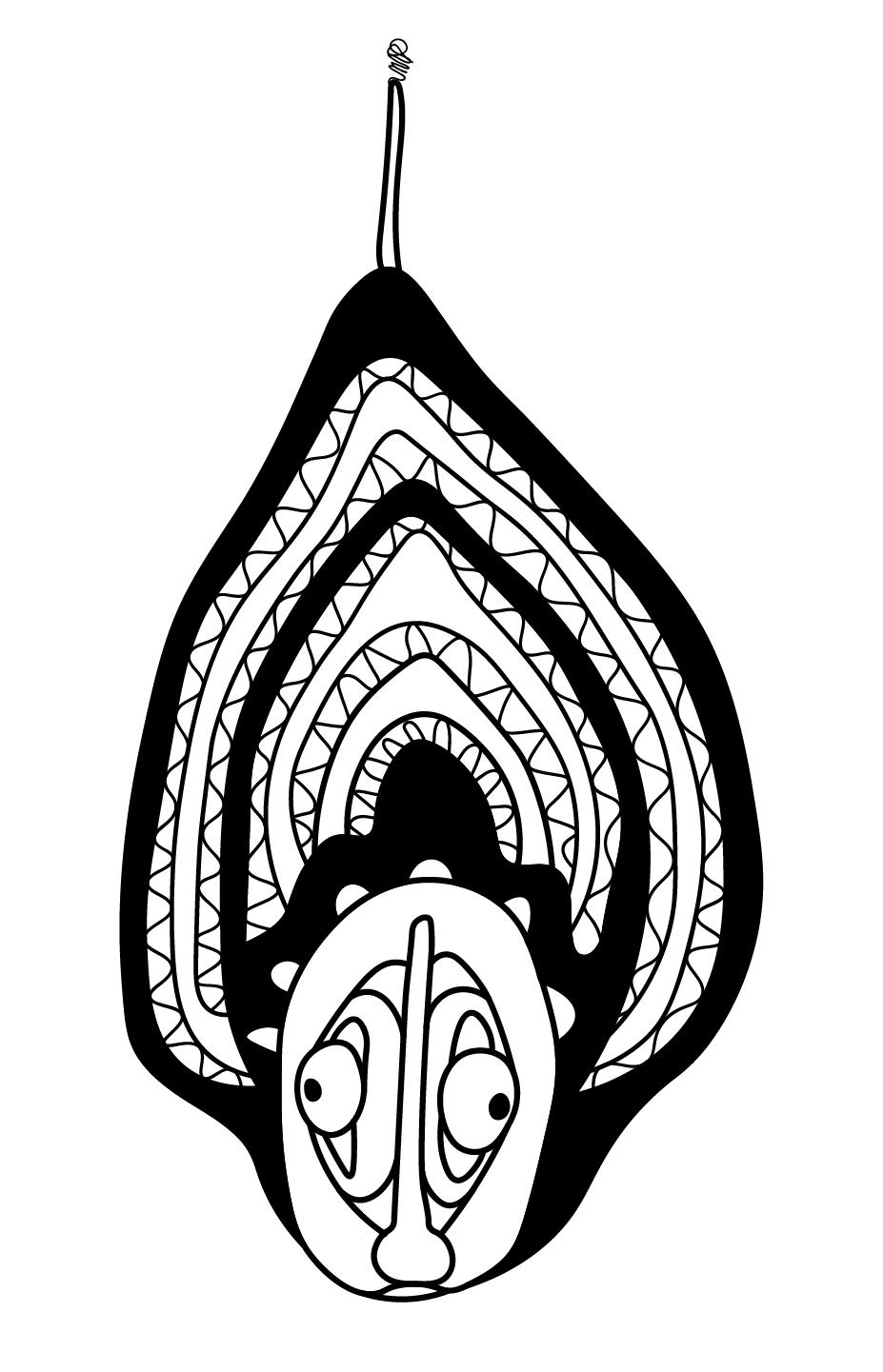

In addition to this supernatural context of fertility across generations, yam production among the Abelam relates directly to politics and power. Each Abelam man has a tchambera or sumbura, an exchange partner, with whom he competes to produce the longest, and therefore most successful, yams. Some Abelam yam varieties have grown to 10 feet long! In harvest ceremonies, partners present yams to their rivals. These long yams are symbolically human, given their ancestral associations and prestige. Yams are decorated with masks, such as the Tje Yam Mask (sketched in Fig. 9.15; original here). There are many photographs of the elaborate displays of long yams with masks in Growing Artefacts, Displaying Relationships: Yams, Art, and Technology Amongst the Nyamikum Abelam of Papua New Guinea (Coupaye 2013).

Using basketry techniques, these masks are woven to represent a face with eyes, linear nose, and small mouth as well as large plumage with patterns reminiscent of feathers. Real feathers and other adornments are often added to the masks. The masks are painted to accentuate the yam during its presentation as a human-like entity. Songs accompany the presentation, creating a spectacle of the harvest and of farmers’ ability to produce extraordinary yams and to metaphorically procreate the human population. Consensus will dictate which man has shown the most prowess. That man earns political status and may take on a leadership role in the community. This is known as an ascribed leadership system, whereby leaders earn their position versus inheriting status through their family line. Among the Abelam, fertility is not only crucial to sustaining life and ensuring new generations will carry on the society. A man’s relationship to fertility of the earth is the foundation of political power.

The Wrap-up

There is much more to learn about how sex, women’s bodies, pregnancy, children, and fertility are expressed in global arts. The next time someone asks you “where babies come from” share some of your art history knowledge. To pursue these ideas further, check out the following media and scholarship to expand your knowledge and make your own connections.

News Flash

- Hannah Gadsby’s stand-up comedy special “Douglas” features art historical gags, including the Venus of Willendorf and many famous artworks of the Western Canon.

- Check out the online magazine The Better India article “Mystery of the Pompeii Lakshmi” to learn about a yakshi figure found in a Roman house in Pompeii!

- Dogū and related Jōmon pottery feature in the video games “The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild” and “Animal Crossing.”

- Maori and related Polynesian cultures are depicted (somewhat problematically) in the Disney movie “Moana.”

- Frida Kahlo is a legend, and rightly so! There have been many documentaries created about her life, including the 2005 Emmy award-winning film “The Life and Times of Frida Kahlo.”

- The Bamana culture is featured alongside the nearby Dogon culture in a Smithsonian National Museum of African Art short film called “Toga Nu and Cheko: Change and Continuity in the Art of Mali.”