12 Social Work with Persons with Disabilities

Emily E. Clarke, BSW and Megan R. Westmore, LMSW

Learning Objectives

In this chapter the student will be reviewing:

- Overview of disabilities and type of disabilities.

- Ableism and strategies for addressing its effects on clients.

- Common issues for disability social workers.

- Overview of American with Disability Act.

Disability and Language

Using respectful language is one of the easiest things social workers can do to build rapport with clients and help create a safer environment for services. It’s also an area that takes work! Language is constantly evolving, and throughout your career as a social worker, you will need to keep up to date with the current, best language to use with a variety of clients. When it comes to your clients with disabilities, there are several language choices to consider. Often people use a lot of euphemisms to refer to disabilities. Euphemisms are words that are substituted into conversations because they are supposedly less harsh or unpleasant. Common euphemisms for disabilities are “special needs,” “differently abled,” and “challenges.” For the most part, advocates with disabilities recommend using the term “disability” rather than any of these euphemisms. After all, “disability” is not a bad word. But even for those who use the term “disability,” there are a couple different options to choose from.

For a long time, the gold standard in the disability field was person first language. As the name implies, a person’s first language emphasizes the personhood of the individual you are talking about and suggests that disability is just one part of a person’s identity (Dwyer, 2022). For example, rather than saying “a disabled person,” you would say “a person with a disability.” Instead of talking about “the Down Syndrome woman,” you would say “the woman with Down Syndrome.” For many individuals, a person’s first language is considered the most respectful choice.

Other people with disabilities prefer identity first language. These advocates stress that disability is an important and valuable part of a person’s identity, and there is nothing disrespectful or wrong about putting disability first (Dwyer, 2022). As an example, someone who was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder may prefer to be called “autistic” rather than “a person with autism.”

So, if some people prefer identity first language and others prefer person first language, which should you use? Ultimately, the best option is to ask your client which language they prefer. People with disabilities are the experts in their lives, bodies, and experiences, and they get to make all decisions about their care, including about what language should be used to refer to them. In this chapter, we will alternate between person first and identity first language.

One other note about language—keep in mind that some disabled people may use reclaimed terms. Reclaimed terms are words that historically have been considered offensive and have been used to speaking negatively about people with a particular identity. Individuals with these identities later reclaim the terminology that has been used against them and use it proudly as a part of their identity (Popa-Wyatt, 2020). For example, some people with physical disabilities may choose to refer to themselves as “crips,” reclaiming this word that in the past was used to oppress them. If you do not have a physical disability yourself, you should be very cautious about using this terminology. It is usually not appropriate for someone without the identity in question to use a reclaimed term.

Social workers with persons with disabilities

Social workers provide services to a variety of populations on a daily basis. One such population is people with disabilities. Disabilities can take many forms, such as physical, cognitive, or mental illness (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). The broad range of potential disabilities can pose many unique challenges for social workers. It is also important to note that while disabilities can be a singular occurrence for some individuals, disabilities often span across many population segments. In fact, about one in four adults in the United States (26%) have some type of disability (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). It is common for people with disabilities to suffer from victimization, stigmatization, and segregation in our society. Therefore, all social workers, no matter what area of social work they are in, should be knowledgeable about the types of disabilities and those who live their lives with them. They must also be able to recognize and address ableism as it arises in their practice.

Below is a video for students to understand social work and disabilities:

Disabilities and their Meanings

There are many different types of disabilities. Sometimes it will be immediately apparent that your client has a disability, and other times they may have what is called an “invisible” or “hidden” disability. These are disabilities that you cannot see just by looking at someone. In fact, you may work with a client and never know that they have a disability diagnosis, so it is important to try to be as accessible as possible in all the work you do. Below is a description of six common types of disabilities: physical, cognitive, mental illness, visual, auditory, and speech. Keep in mind that some clients may also have multiple types of disabilities.

Physical Disabilities

Physical Disability: a limitation on a person’s physical functioning, mobility, dexterity, or stamina. Physical disabilities can take many forms and can occur at any time in an individual’s life. Many physical abnormalities can occur before a person is born, developing in utero. Known as congenital disorders, these impairments can take many forms. Some can be as minor as a birth mark or as severe as a missing limb or internal abnormalities (Nemours, 2017). Sometimes congenital disabilities are referred to as birth defects, but that term is often considered offensive and outdated, so the appropriate description is congenital disability. When a congenital disability proves to be severe and long lasting, it has the potential to develop into a lifelong disability. Infants born with missing limbs or improperly developed physical traits will often grow to have a physical disability. Some physical congenital disabilities can be corrected or improved with medical technology, such as surgeries to correct cleft palates; however, there are many that cannot be corrected, potentially leading to a physical disability.

There are also physical disabilities that occur after birth at any time in an individual’s life. Major accidents are the most common cause of physical disabilities after birth. Car accidents are common accidents that can cause physical disabilities at any time in life. Car accidents can lead to minor injuries, but in severe cases can cause lifelong physical disabilities such as severed limbs, brain, and spinal cord injuries (Disabled World, 2015).

Military personnel are also at substantial risk of procuring physical disabilities through outside means. War can lead to various physical disabilities due to military engagements. The most recent military conflicts have led to high numbers of physical disabilities resulting from IEDs (Intermittent Explosive Devices) which have caused loss of limbs, spinal cord injuries and traumatic brain injuries.

Physical disabilities can impact individuals in a variety of ways. Depending on the nature of the physical impairment individuals may be limited to where they can travel, and the type of employment they can procure. Social workers must be prepared to not only address the physical limitations that a physical disability can pose, but also the emotional impact that one may have on a client. Working with clients who have a physical disability can be a unique and rewarding experience. Each client will require an individualized approach, as not everyone who has a physical disability will cope in a uniformed way.

Cognitive disabilities

Cognitive disabilities, also known as intellectual disabilities, are other forms of disabilities that social workers will encounter in the field. There are many types of cognitive disabilities that can vary in impact, but all affect a person’s mental functioning and skills to some extent.

Some common types of cognitive disabilities are:

- Autism

- Down Syndrome

- Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

- Dementia

- Dyslexia

- ADHD

- Learning Disabilities

Cognitive disabilities, like physical disabilities, can be present at birth. Any disability that develops before someone reaches the age of 22 is also called a “developmental disability.” Some cognitive disabilities at birth can be almost impossible to distinguish and usually begin to be present in early childhood. Some indicators of cognitive disabilities can be present in infancy, such as the infant failing to meet certain milestones or presenting unusual symptoms such as lack of sleep and inconsolable crying. While these indicators can be present, it is often difficult for medical professionals to diagnose cognitive disabilities in infants and toddlers.

Most cognitive disabilities are diagnosed in childhood and early adolescence. There are several assessments that can be conducted to determine the presence of a cognitive disability. While many medical professionals may suspect a cognitive disability, most often patients are referred out to have the appropriate assessments completed. Once a diagnosis is made there are several forms of therapy that can be performed depending on the type of cognitive disability, and early intervention at young ages can be hugely beneficial.

Even with the advancements in medical technology, there are no “cures” for cognitive disabilities. While various therapies and some medications can help improve cognition and stall deterioration in some, there is no way to fully heal the cognitive disability. Professionals can, however, make many adaptations and accommodations to provide the most accessible services possible to people with these disabilities. Cognitive disabilities can impact individuals on many levels, from employment to personal relationships. With the proper support, people with cognitive disabilities can work, live, and play in their communities. Social workers working with this population must be prepared for the diversity within and the individual challenges faced by those with cognitive disabilities.

The chapter began with a discussion of respectful language, and there are some terms used with people with cognitive disabilities that are worth unpacking. When working with clients with cognitive disabilities, you should avoid using mental age theory. Mental age theory is when someone refers to an adult with a cognitive disability as having the mind of a child (Smith, 2017). It might sound something like, “She is 25, but has the mind of a 5-year-old.” Self-advocates with intellectual disabilities have spoken against this language, explaining that it is disrespectful and hurtful to them. If you find yourself wanting to use this language, take a minute to reflect on what it is you are trying to communicate. What do you mean when you say someone has the mind of a 5-year-old? How could you communicate what you are trying to say differently? For example, you might say something like, “She is 25, but uses pictures to communicate,” or “She is 25, and needs you to talk to her in short sentences of no more than a few words.” Likely there are many other ways you can communicate valuable information about your client without using language that is disrespectful. Never treat adult clients with cognitive disabilities like they are children.

Mental Illness

Mental Illness is considered a wide range of mental health conditions — disorders that affect mood, thinking and behavior. (Merriam-Webster’s collegiate dictionary, 1999)

While many may not consider mental illness to be a category of disability, there are several mental illnesses that impact an individual’s life in such a way that it can be classified as a disability. Mental illnesses such as Schizophrenia, Borderline Personality Disorder, and bipolar disorder can be so severe that an individual’s everyday life is impacted. When a mental illness impairs an individual’s ability to function, it can be considered a disability.

For some mental illnesses, medication can help alleviate symptoms. This is especially true regarding disorders such as Schizophrenia and Bipolar disorder. While there is no cure for these disorders, medication in combination with behavioral therapies can reduce the symptoms. However, there are some mental illnesses that even with medication and therapy can still make coping difficult.

Agoraphobia is a disorder that causes fear of places and situations that might cause panic, helplessness or embarrassment. This is one disorder that can severely impact everyday functions, to the point where the individual may not even be able to leave their home due to anxiety.

Mental illnesses in themselves can be considered disabilities when they impact an individual’s life to the point of impairing functioning. Mental illnesses can also contribute to other health concerns and behavioral symptoms that impact lives.

Visual disabilities

Individuals with visual disabilities, also sometimes called visual impairments, have a decreased ability to see, even when using glasses or contact lenses. People who are blind may have no ability to see, or very limited usable vision (American Foundation for the Blind, 2020). Visual disabilities may be congenital or can be acquired through disease or injury. Individuals who are blind or have visual impairments may use a variety of strategies to navigate through the world, such as using a guide dog or a mobility cane. Always ask before providing assistance to someone with a visual disability. Remember, they are the experts on their bodies, and they can best decide if they even need help, and if so, how they would like to be helped.

Auditory disabilities

Auditory disabilities impact an individual’s ability to hear sounds, and hearing loss occurs on a spectrum. Deaf individuals have little to no functional hearing, while those who are hard of hearing have some degree of hearing loss and ability (Disabilities, Opportunities, Internetworking, and Technology, 2021). Other terms individuals in this community use are deafblind (for people with hearing and visual disabilities), deaf disabled (for people with hearing and other types of disabilities), or late-deafened (for people who become Deaf later in life) (National Deaf Center, n.d.). Many Deaf people use American Sign Language (ASL) to communicate. They may not identify as having a disability, but rather see deafness as a cultural group with its own language, traditions, and values.

Speech disabilities

Speech disabilities impact an individual’s ability to create the sounds needed to communicate with others (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, 1993). Many speech disabilities are physical in nature, meaning the individual may have typical cognitive functioning. As you work with a client with a speech disability, you will likely learn more about their speech patterns and be better able to understand them. Never pretend to understand someone if you do not. It is better to ask a client to repeat themselves, or rephrase their statement, than to miss what they are trying to communicate.

Ableism

While it is important for social workers to know about a variety of disabilities, what may be even more crucial in your practice is the ability to recognize and address ableism. Ableism is a system of discrimination based on the false belief that disabled people are inferior to nondisabled individuals. It is a form of discrimination in which disabled people are oppressed and nondisabled people are privileged (Conley & Nadler, 2022). Unfortunately, ableism is deeply ingrained in our society, and it can take many forms. One such form is physically inaccessible rooms. Think about the spaces where you spend time—your home/apartment, school, workplace, favorite coffee shop, etc. How accessible would those spaces be for someone who uses a wheelchair? Would they be able to easily enter the space, navigate through it, and exit? Surprisingly, the answer to these questions is often “no.” Social work agencies need to regularly review their spaces to ensure they are accessible for all clients, including those with disabilities.

Ableism also shows up in the form of assumptions and prejudices. For example, there is a false stereotype that people with disabilities are asexual. This false belief leads to many harmful practices, such as denying disabled people access to sexuality education (Shandra & Chowdhury, 2012). Discrimination can also cause employers to not hire people with disabilities, contributing to disproportionately high rates of unemployment among disabled people in the United States (Friedman & Rizzolo, 2017). Ableism also leads to people with disabilities experiencing higher rates of violence, such as sexual assault, than their nondisabled peers (McGilloway et al., 2018). These are just a few examples of the devastating consequences of ableism.

Below is a video for the student to understand ableism from a person with a disability perspective:

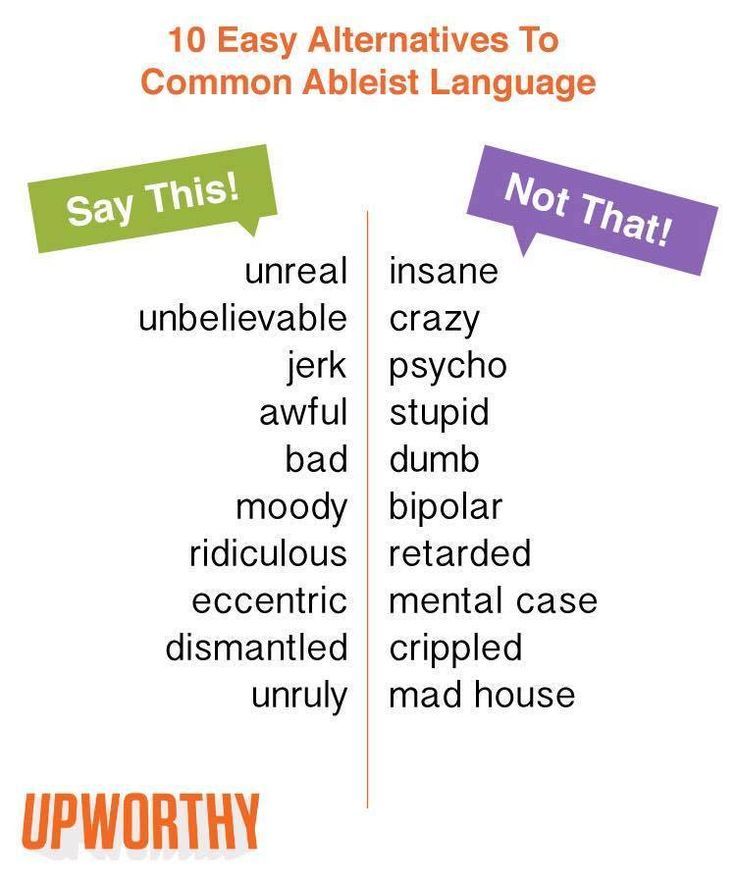

Ableism can even show up in the language we use! Sometimes, when a person rapidly changes their mind, or is acting in a way that we perceive to be overly emotional, we might say things like, “Oh, he was being so bipolar.” When we say things like this, we do not stop to think about the fact that being bipolar is someone’s actual lived experience, and it is not appropriate or respectful to use someone’s disability to insult someone else. Take a look at the list of words on the right side of the figure below. How many of these words do you use on a regular basis? If you are like most people; you use many of them a lot! Ableism is so common that it creeps into our daily conversations without our conscious awareness. We can all make efforts to use language that is less ableist. In the sections to follow, we will also talk about other ways you can address ableism in your social work practice.

Models of Disability

There are several models that can be used to understand disability and ableism. Three of the most common are the medical, social, and human rights models.

Under the medical model of disability, the person is understood to be disabled by their physical or cognitive condition. Individuals who subscribe to this model believe that the problem is the disability itself, and much of the focus of funding and interventions is on seeking a cure for the disability. This model puts the responsibility on the person with a disability to “overcome” the disability and adapt to the society around them. For example, if a student with dyslexia is struggling to read on grade level with her peers, the medical model would state that the problem is the student’s cognitive abilities.

The social model of disability, on the other hand, suggests that the person is disabled not by their body or mind, but by the inaccessible world our society has created. Advocates who use this model explain that we need to make accommodations to our environments and services, so they are accessible for disabled people. Disability is seen as a normal part of humanity, and it is our collective responsibility to ensure that we create spaces and services for all people. Returning to our example of the student with dyslexia who is not reading on grade level, the social model of disability suggests the problem is not the student’s disability, but rather the strategies her teachers are using to teach her to read. Accommodations need to be made for her disability, so she is better able to learn.

One of the more recently developed approaches is the human rights model of disability. This model emphasizes that disability is a normal part of human diversity, and that disabled people must have the same rights as everyone else. While there are many overlaps between the social and human rights models of disabilities, the human rights model acknowledges that there are some difficult aspects of certain disabilities, such as chronic pain or shorter life expectancy, that will still exist even after societal barriers are removed. This model suggests that individuals should also receive support for these parts of their disability that cannot be addressed through environmental and service accommodations alone (Disability Advocacy Resource Unit, n.d.). Even after the student with dyslexia receives education tailored to her needs, it still may take her extra time to read or to “catch up” to her peers, and she may be frustrated by this process. The human rights model says that we need to advocate for her rights to be treated with respect and care as she reads in the way that works best for her.

Social workers tend to follow the social and human rights models of disabilities. We understand that we have a responsibility to provide accessible services to our clients with disabilities, and to ensure their rights are being respected. The following video provides additional information on these disability models.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

Social workers not only have an ethical responsibility to serve individuals with disabilities, but also a legal one. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was put into place in 1990. It guarantees equal rights for those with disabilities in the United States. It prohibits discrimination against those with disabilities “in all areas of public life, including jobs, schools, transportation, and all public and private places that are open to the general public” (ADA National Network, 2017). The purpose of the ADA is to allow the same opportunities and rights to those with a disability as everyone else. While this policy has created great advancements for those with disabilities, especially in education and employment, discrimination still takes place daily in our country.

Not everyone with a physical, cognitive, or mental health disability is limited in the same ways and the world has developed to allow more access for those with a physical disability. The Americans with Disabilities Act has helped individuals with disabilities not only because it prohibits discrimination in all areas of public life, but it has also opened many opportunities for individuals with disabilities to gain independence.

Accommodations

One responsibility all social workers have under the ADA is to provide reasonable accommodations for their clients with disabilities. Accommodation allows someone to do something they would not otherwise be able to do, or it makes it easier for them to do these things. All of us have used accommodations at some point in our lives. Perhaps you use spell check before turning in your homework. Or maybe you use a pill box to separate your pills by the day of the week to ensure you are taking your medication properly. Both things are accommodations! There are many different types of accommodations, but we will go over a few common ones here.

- Accessible language: Have you ever signed a consent document without understanding exactly what you were signing? Many of us have! Too often the language used on intake and consent forms is so complicated that it is no longer understandable for clients. In your social work practice, you are likely to encounter countless opportunities to practice using more plain, concrete, and accessible language. This will not only help you to better communicate with clients with cognitive disabilities, but it will likely be helpful for all your clients, including those without disabilities. If you have the opportunity to design forms, handouts, and/or flyers for clients, take a moment to check the readability of your document before finalizing it. You can also try to use less technical and more accessible speech when you talk to clients. Keep in mind that the average US resident reads at a 7th grade level, and this level is likely to go down by one or two grades when someone is stressed (Taylor, 2018). Using more accessible language will help you better accommodate clients with disabilities and will also be more trauma-informed when working with any clients who have experienced stressors.

- Physical devices: Many physical devices are also used as accommodations. For example, someone might use a wheelchair, cane, or walker to physically navigate through a space. A hearing aid might improve someone’s ability to communicate with others. Or a grabber might be used to reach items on a high shelf.

- Changes to the environment or service: Sometimes you might make accommodations for your clients by changing the environment or service provided. If you are working with an autistic client who is sensitive to sensory inputs, you might turn off the overhead light and instead use lamps in your office, or you may seek a quieter space within your building to meet. You might look at the steps leading into your office and advocate for a ramp to be built. All of these are examples of changes made to the physical environment in order to accommodate clients with disabilities. You can also accommodate individuals by adapting your services. If you are working with someone with an intellectual disability, you might pull up pictures on one of your electronic devices to better communicate with your client. Or if you need someone with a visual disability to sign a document, you could either read the document out loud, or send it to them electronically so they can use a screen reader on their device to review the document.

- Paid Services: Sometimes disabled people use paid services as an accommodation. For instance, your agency may need to contract with an ASL interpreter to work with a Deaf client. Or someone with a physical disability may have a paid personal care attendant who assists them with things such as using the restroom or driving to appointments.

This list of accommodations only barely scratches the surface of the many different types of accommodations you can make for clients in your practice. More often than not, accommodations are simple and low-cost. You do not need to know every possible accommodation that exists—that would be impossible! What’s most important to remember is that the disabled client is the expert in their experience. They know their body and mind best, and they can tell you what accommodations would be most helpful. Allow the client to determine what kind of accommodation you provide.

Sometimes, you may also have to advocate with and for your client for an accommodation. For example, you might ask if your agency has money in its budget for ASL interpretation. If not, why not? Or perhaps your agency does not typically allow someone to have a support person present during services, but your client needs their personal care attendant present to access your services. Part of disability allyship is being willing to advocate for your client on micro, mezzo, and macro levels. This is important for social justice reasons, but also because we are all likely to experience temporary or permanent disability at some point in our lifetimes, either due to an accident or the effects of aging (World Health Organization, 2011). Designing accessible services and environments is beneficial for all.

Competencies for the social worker with individuals with disabilities:

- Basic to the social worker’s work with those with disabilities is the core belief that persons with disabilities are equals, and a willingness to advocate for any anti-ableist attitudes and social inclusion.

- Such competency will certainly include the social worker’s willingness to advocate for access to needed resources and for the client’s competency in decision- making.

- The social worker demonstrates respect for those with disabilities in their incorporation of respectful language, joining advocacy efforts, and challenging beliefs that persons must “overcome” their disabilities.

- Practice competencies would include the following:

- A social worker’s practice being person-centered as well as engaging the person in decisions impacting their life.

- Practice from a strengths-based perspective that focuses on the person’s existing strengths and resources.

- Attend to any situations or conditions that are challenging persons with disabilities and their family or support network.

Summary

People with disabilities face challenges in modern society that other population segments do not experience. With the various and sometimes limited resources offered, social workers must know how to navigate a system to better provide for their clients. With the rising cost of healthcare and an ever-changing political environment, social workers are tasked with advocating and serving those in the population who may need additional services navigating around the less than accessible parts of the world we live in. People with disabilities are valuable contributing members of our world and as social workers we must stand to make a better future for all.

REFERENCES

ADA National Network. (2017). What is the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)? Retrieved from https://adata.org/learn-about-ada

American Foundation for the Blind. (2020, October). Key definitions of statistical terms. https://www.afb.org/research-and-initiatives/statistics/key-definitions-statistical-terms

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (1993). Definitions of communication disorders and variations. https://www.asha.org/policy/rp1993-00208/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2016). Disability overview: Impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/disability.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020, September 16). Disability impacts all of us. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/infographic-disability-impacts-all.html#:~:text=61%20million%20adults%20in%20the,is%20highest%20in%20the%20South.

Conley, K. T., & Nadler, D. R. (2022). Reducing Ableism and the Social Exclusion of People With Disabilities: Positive Impacts of Openness and Education. Psi Chi Journal of Psychological Research, 27(1), 21–32. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uta.edu/10.24839/2325-7342.JN27.1.21

Disabilities, Opportunities, Internetworking, and Technology. (2021, April 9). How are the terms deaf, deafened, hard of hearing, and hearing impaired typically used? https://www.washington.edu/doit/how-are-terms-deaf-deafened-hard-hearing-and-hearing-impaired-typically-used

Disability Advocacy Resource Unit. (n.d.). How does the human rights model differ from the social model? https://www.daru.org.au/how-we-talk-about-disability-matters/how-does-the-human-rights-model-differ-from-the-social-model

Disabled World. (2015). Accidents and disability information: Conditions and statistics. Retrieved from https://www.disabled-world.com/disability/accidents/

Dwyer, P. M. A. (2022). Stigma, incommensurability, or both? Pathology-first, person-first, and identity-first language and the challenges of discourse in divided autism communities. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 43(2), 111-113. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000001054

Friedman, C., & Rizzolo, M. C. (2017). “Get us real jobs:” Supported employment services for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities in Medicaid Home and Community Based Services Waivers. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 46(1), 107–116. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uta.edu/10.3233/JVR-160847

Kids Health. (2017). Birth defects. Retrieved from https://kidshealth.org/en/parents/birth-defects.html

McGilloway, C., Smith, D., & Galvin, R. (2020). Barriers faced by adults with intellectual disabilities who experience sexual assault: A systematic review and meta‐synthesis. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 33(1), 51–66. https://doi-org.ezproxy.uta.edu/10.1111/jar.12445

Merriam-Webster’s collegiate dictionary (10th ed.). (1999). Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster Incorporated.

National Deaf Center. (n.d.). Defining deaf. https://www.nationaldeafcenter.org/defining-deaf

Popa-Wyatt, M. (2020). Reclamation: Taking back control of words. grazer philosophische studien, 97(1), 159-176.

Shandra, C. L., & Chowdhury, A. R. (2012). The first sexual experience among adolescent girls with and without disabilities. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41, 515–532. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-011-9668-0

Smith, I. (2017, September 7). Mental age theory hurts people with intellectual disabilities. NOS Magazine. http://nosmag.org/mental-age-theory-hurts-people-with-intellectual-disabilities/?fbclid=IwAR3rIowvza–suPeczRKzMiw0CAKCtfQEc92vS6RyacqUD6zBAJ80rUB8Lk

Taylor, Z. W. (2018). Unreadable and underreported: Can college students comprehend how to report sexual violence? Cultivating safe college campuses conference. docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/7c1e05_885eec3ce6c1425bb4c0cd6947c7638d.pdf

Workplace Fairness. (2017). Disability discrimination. Retrieved from https://www.workplacefairness.org/disability-discrimination

World Health Organization. (2011). World Report on Disability (Rep.). Geneva, Switzerland.