1 Introduction to Multimodal Transportation Planning

Chapter Overview

This chapter introduces multimodal transportation planning. It begins by defining multimodal transportation and exploring the benefits of modal diversity for system users and society. The multimodal transportation planning process is described, including several considerations when integrating transportation and land use. Traditional and contemporary planning practices are compared, including a review of biased and objective language in transportation planning. Overall, this chapter provides a framework for a conceptual understanding of multimodal transportation planning and introduces concepts and methods that will be explored throughout the book in more detail.

Chapter Topics

- Overview of Multimodal Transportation

- What is Multimodal Transportation Planning?

- Why is Multimodal Transportation Planning Important?

At the completion of this chapter, readers will be able to:

- Define multimodal transportation planning

- Describe the relationship between land use and transportation as it relates to accessibility

- Identify the need for and benefit of a diverse transportation system

- Differentiate between traditional transportation planning and multimodal transportation planning

Overview of Multimodal Transportation

Transportation is how we overcome spatial distances between activities. A transportation system includes facilities and services that provide mobility and access for people and goods. Multimodal planning recognizes that mobility involves more than through movement of vehicles. Mobility is the ability of people to move between origins and destinations using various modes of transportation. Accessibility is an areawide measure of the ease with which people can move between defined geographic areas to access desired activities and services. It includes the ability to reach a given location from numerous other locations or the ability to reach a variety of other locations from a given location (Williams & Seggerman, 2014).

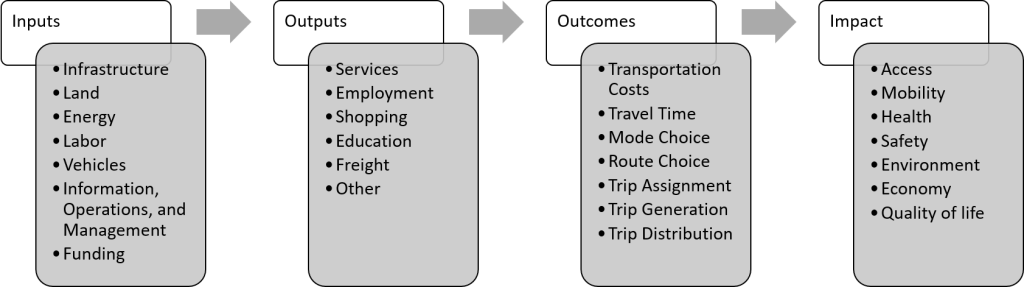

Transportation systems are complex and the functions are interrelated. The characteristics of a transportation system can be explained in terms of inputs, outputs, outcomes, and impacts (Figure 1.1). To conceptualize the transportation system, think of it as a means to an end. In a look at resiliency, Weilant et al. (2019) explains that “the transportation system—a system within a larger system in a given geographic area—uses transportation services as a means to achieve the well-being of the transportation system and other systems, otherwise known as the ends” (p. 17). In other words, the inputs contribute to the outputs, outcomes, and ultimately, the impact that the transportation system has on its users, whether positive or negative.

Figure 1.1. Inputs, outputs, outcomes, and impacts of transportation

Figure 1.1. Inputs, outputs, outcomes, and impacts of transportation

Source: Adapted from Levinson, 2021, CC BY-SA 4.0

There are seven categories of transportation inputs that include the following:

- Infrastructure – includes highways, local roads, and rail (for drivers and autonomous vehicles), and gray and green infrastructure, such as pathways for pedestrians, bikes, scooters, and powered wheelchairs (Weilant et al., 2019).

- Land – relates to the land use type and pattern, scale and spatial structure, and urban form. Transportation and land use interact cyclically. Land use in this context relates to the movement of people between activities and land uses and land consumed for transportation infrastructure (Rodrigue, 2020).

- Energy – energy used for transportation includes petroleum products (products made from crude oil and from natural gas processing, including gasoline, distillate fuels (mostly diesel fuel), jet fuel, residual fuel oil, and propane), biofuels (ethanol and biomass-based diesel/distillates), natural gas, and electricity (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2021).

- Labor – planners, engineers, construction staff, operations staff, public transportation providers (such as bus drivers and train conductors), and policymakers (Weilant et al., 2019).

- Vehicles – can be divided into modes (e.g., roadway, rail, water, air).

- Information, Operations, and Management – relates to the strategies in place to manage and maintain the transportation system.

- Funding – revenue sources for transportation include funding at the federal, state, and local levels.

Outputs are divided into two categories. The first category focuses on the movement of people between origins and destinations for a variety of purposes. The second category is goods movement, also referred to as freight or the distribution of items such as raw materials, parts, and consumer products. The transportation system helps move freight on freight facilities such as (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2016):

- Seaports, airports, and border crossings

- Railyards and rail lines

- Marine highways

- Highways and high truck traffic roads

- Warehouse and distribution facilities

Outcomes refer to the system’s performance. Transportation outcomes may include transportation costs, travel times, mode choice, trip generation, and trip distribution. Finally, the impacts of the transportation system may be positive or negative. These include access, mobility, health, safety, the environment, the economy, and socialization/community cohesion.

Transportation can be divided into different modes (e.g., roadway, rail, water, air). Each mode has varying benefits and limitations for its users and the broader transportation system. To this end, transportation system users may use different combinations of modes in the same trip. For example, a person who rides public transportation will walk or cycle to the transit stop. A bike share user will walk from the docking station to their destination. Combining modes in this manner is indicative of multimodal transportation. An understanding of modal needs and the interconnectedness of modes is key to planning a safe and efficient multimodal transportation system.

What is Multimodal Transportation Planning?

Multimodal transportation planning is the integration of transportation and land use to provide diverse mobility options that meet the needs of various system users. To ensure the safe, efficient movement of all system users, multimodal transportation planning considers land use, system connectivity, and the interconnectedness of various modes. According to Litman (2021a), this should translate to “integrated institutions, networks, stations, user information, and fare payment systems” (p. 16). Transportation planning is a comprehensive process that should consider possible strategies, include an evaluation process that encompasses diverse viewpoints, ensure the collaborative participation of relevant transportation-related agencies and organizations, and include open, timely, and meaningful public involvement (FHWA, n.d.).

*

Traditional versus Contemporary Transportation Planning

The concept of “predict and provide” has traditionally been a driving force behind transportation planning. This planning process is characterized by anticipating future land use based on adopted future land use plans and analysis of market and growth trends in a community or region. It tends to react to, rather than attempt to shape, future growth and offers limited solutions to transportation needs – seeking primarily to accommodate rather than manage vehicular traffic demand.

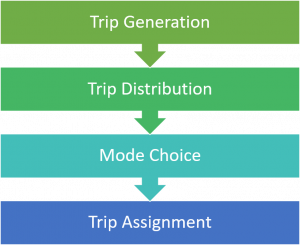

In this process, a four-step model (shown in Figure 1.2) forecasts demand resulting from the locally adopted land use plan and predicts traffic congestion on specific links in the roadway network. Solutions derived from traditional processes typically involve expanding roadway capacity by adding new lanes and incorporating some system management strategies, such as turn lanes at intersections and signal coordination.

Figure 1.2. Traditional four-step transportation/land use model

Contemporary transportation planning integrates transportation and land use, placing more emphasis on expanding and reinforcing mode choice. Strategies emphasize multimodal investments and focus on facilities and services that manage and influence demand by expanding mode choice, providing efficient connections between modes, and coordinating land use decisions. According to Williams & Seggerman (2014), a diverse and compatible mix of land uses, along with “[d]ense, connected streets with narrower cross-sections and wider, continuous sidewalks are among the determinants of walkability, and also help to make activity centers functional, vibrant, and appealing” (p. 6). In this light, contemporary transportation planning is also (Florida Department of Transportation: District 5, 2011):

- Context-sensitive: looks at the broader context rather than focusing on solutions within the right-of-way, a single roadway, or a few intersections;

- Holistic: identifies transportation solutions that address broader land use issues and integrate land use and transportation for the long-term viability of the corridor and community;

- Collaborative: forms intergovernmental partnerships to identify and implement strategies that leverage the full value of all infrastructure investments; and

- Multimodal: examines pedestrian, transit, bicycling, and automobile travel and identifies supporting land use strategies.

Strategies to Shift to Multimodal Transportation

- Change the mindset of transportation system users by articulating and implementing a steady program of interventions to demonstrate the benefits of a more balanced policy package to multiple constituencies.

- Provide improved transit, walking, and biking alternatives to mobile underserved commuters—who use either transit or cars.

- Implement consistent policies and more integrated planning to coordinate road space reallocation needs with strategic improvements in public transportation alternatives.

- Ensure real community participation to generate new solutions to problems, increase the legitimacy of decisions, and mitigate implementation risk.

- Encourage local stakeholders to advocate for quick-win, incremental improvements—proper sidewalks, safe routes to schools—while the more time-consuming and large-scale interventions related to modernizing transit networks are underway at a systemic level.

- Identify diverse revenue sources to invest in transportation infrastructure that supports multimodal transportation.

- Engage in public-private partnerships to develop transit-supportive land uses and share the benefits of enhanced multimodal transportation.

- Target subsidies toward specific user groups such as low-income communities for whom affordability is a key constraint on their mobility.

Source: Adapted from Venter et al. (2019)

Planning Considerations

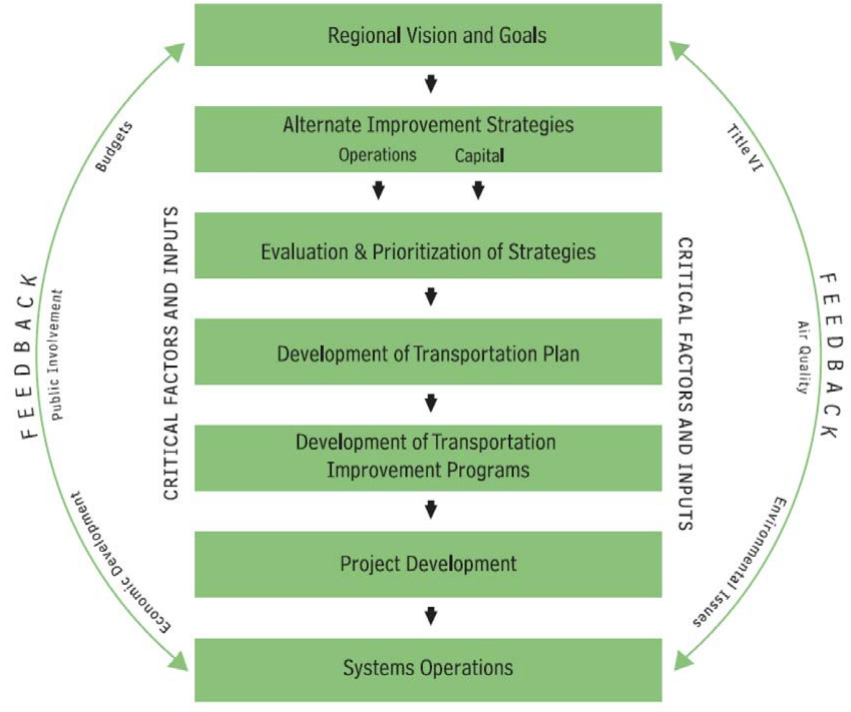

Figure 1.3 shows planning considerations and the transportation planning process. Generally, this process includes developing a vision, goals, and objectives, examining existing and future conditions, identifying and assessing needs, developing strategies to address those needs, selecting and prioritizing projects, funding and implementing projects, and monitoring system performance.

Figure 1.3. The transportation planning process

Source: Adapted from FHWA, n.d., Public Domain

Transportation planning must also consider a variety of laws including the following:

- Land Use (state and local law)

- Clean Air and Air Quality (Clean Air Act and Air Quality Standards)

- Environmental Policy (National Environment Policy Act (NEPA)

- Environmental Justice (Title VI)

- The Americans with Disabilities Act

- Presidential directives and Federal guidance as outlined in Executive Orders and other initiatives

Multimodal transportation planning best practices

Multimodal transportation planning should consider the following:

- A variety of transportation improvement options.

- All significant impacts, including the following:

- Congestion

- Roadway, parking, and consumer costs

- Traffic crashes

- Quality of access for non-drivers

- Energy consumption

- Pollution emissions

- Equity impacts

- Physical health

- Land use development impacts

- Community livability

- A comprehensive and marginal comparison of modes to ensure appropriate scale and scope.

- The quality of mobility options, particularly for disadvantaged and underserved populations.

- Strategic planning objectives for long-range land use and economic development.

- Comprehensive transportation models that consider multiple modes, generated traffic impacts (the additional vehicle traffic caused by expansion of congested roadways), and the effects of various mobility management strategies such as price changes, public transit service quality improvements, and land use changes.

- Methods to provide people involved in transportation decision-making the opportunity to experience non-motorized transportation, if they do not already do so in their daily commute.

Source: Adapted from Litman (2021a)

Biased and Objective Language in Transportation Planning

The language used in transportation plans and related documents often reflects certain biases of traditional transportation planning practice. When planning for multimodal transportation options, it is important to contemplate the words used and consider their implications to avoid these biases. In particular, traditional terms used in transportation demonstrate a preference for automobile travel. For example, the term “improvement” is value-laden and often used to describe roadway widening projects. Such projects may or may not improve conditions for different modal users. A shift from biased language to more neutral and multimodal language ensures positive change for multimodal transportation and ensures clarity when communicating about plans, studies, projects, and so on. Table 1.1 illustrates the differences between biased and neutral terms used in transportation.

Table 1.1. Biased versus objective language used in transportation

| Biased Language | Objective Language |

|---|---|

| Traffic | Motor vehicle traffic, pedestrian traffic, bike traffic, etc. |

| Trips | Motor vehicle trips, person trips, bike trips, etc. |

| Improve | Change, modify, expand, widen |

| Enhance | Change, increase |

| Deteriorate | Change, reduce |

| Upgrade | Change, expand, widen, replace |

| Efficient | Faster, increased vehicle capacity, reduced delay |

| Level of service | Level of service for… |

| Accident | Collision or crash |

| Alternative transportation | Active transportation/human-powered/non-automobile |

| Desirable/Acceptable | Desirable (for whom)/Acceptable (for whom) |

| Enhanced | Increase/Reduced (depending on the subject) |

| Impact (noun) | Effect |

| Reliable | Predictable travel time |

Source: Lockwood, 2004 as cited by Litman, 2021b and Lockwood, 2017

Multimodal Environment Elements and Criteria

The multimodal environment includes several elements that relate to the organization and location of land uses, land use mix, density and intensity of development, and related multimodal policies (Williams et al., 2010). Mode choice and mobility are influenced by the organization and location of land uses. Activity centers are a good example of how land use can support the multimodal environment in this way. An activity center is “a compact node of development containing uses and activities which are supportive of and have a functional relationship with the social, economic, and institutional needs of the surrounding area” (Williams et al., 2010, p. 8). Activity centers include urban cores, suburban shopping and employment centers, transit hubs, and industry and freight centers. These areas are typically characterized by bicycle and pedestrian friendly environments and provide more efficient transit services.

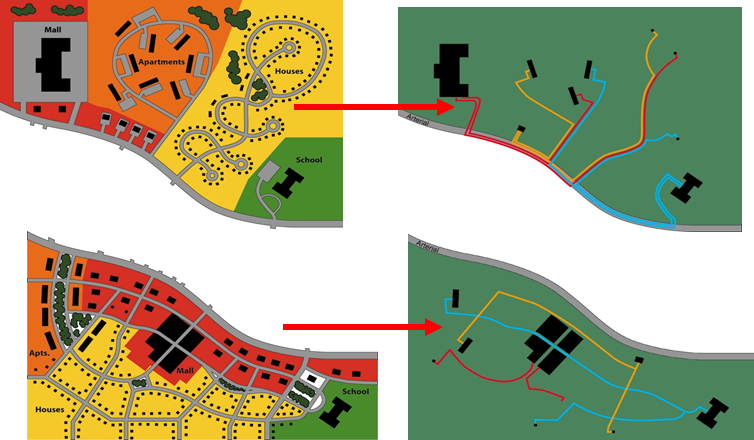

Figure 1.4 illustrates the relationship between network, land use mix, and trip making on major roadways. As described by Williams et al. (2010):

The top example reveals how separate, stand-alone land uses require the use of the arterial for even short local trips due to the absence of network connections. This increases the need to drive among uses, rather than walk or bike, due to longer local travel distances. The bottom example shows how land uses can be organized on a connected network to create an environment that supports non-automobile modes, reduces vehicle miles of travel, and internalizes local trips (p. 6).

Figure 1.4. Land use organization, network connectivity, and arterial traffic

Source: Williams et al., 2010, Public Domain

Land use mix and development density and intensity support transit, walking, and bicycling when coupled with a well-connected street system. The proximity of key destinations to each other and to residential uses can reduce the number and length of vehicular trips, make daily travel more convenient, and provide access to more modal options.

Multimodal transportation is also supported by development density and intensity in centers and near transit. In traditional land use planning, maximum densities are generally established using either dwelling units per acre or floor area ratios. Multimodal planning involves consideration of minimum, rather than maximum, densities in areas to be served by transit. Finally, the elements of the multimodal transportation system become implementable with policies that prioritize pedestrians and cyclists, parking management, streetscapes, and transit station area amenities. The 5 D’s of transportation are described in more detail in Chapter 4.

*

The 5 D’s of Land Use and Transportation

Density: population and employment by geographic unit

Diversity: mix of land uses

Design: neighborhood layout and street characteristics

Destination accessibility: ease or convenience of trip destinations from point of origin

Distance to transit: ease of access to transit from home or work

Source: Adapted from Ewing & Cervero (2010)

Accessibility and Mobility

Earlier in this chapter, transportation was defined as “facilities and services that provide mobility and access to move people and goods.” Accessibility and mobility, both of which require the integration of transportation and land use, are key when planning for a multimodal transportation system. For example, incorporating activity center concepts into the transportation element of a comprehensive plan lays the foundation for effective multimodal transportation systems in the future. The result is a plan that includes and identifies areas where walkable and compact urban development is desired and guides decisions and investments for future street design and facilities for public transportation, walking, and cycling (Williams & Seggerman, 2014).

Accessibility measures how easily people can travel between locations within a defined geographic area, as discussed in Chapter 8. Accessibility can be assessed by evaluating the capacity and arrangement of transportation facilities and land use, such as the proximity and mix of jobs, shopping, community centers, and other activities.

Mobility measures the ability of people to make trips to meet their needs using any combination of transportation modes. Planning processes that support all modes of travel requires practitioners to change their perspectives on transportation from moving vehicles to moving people and goods.

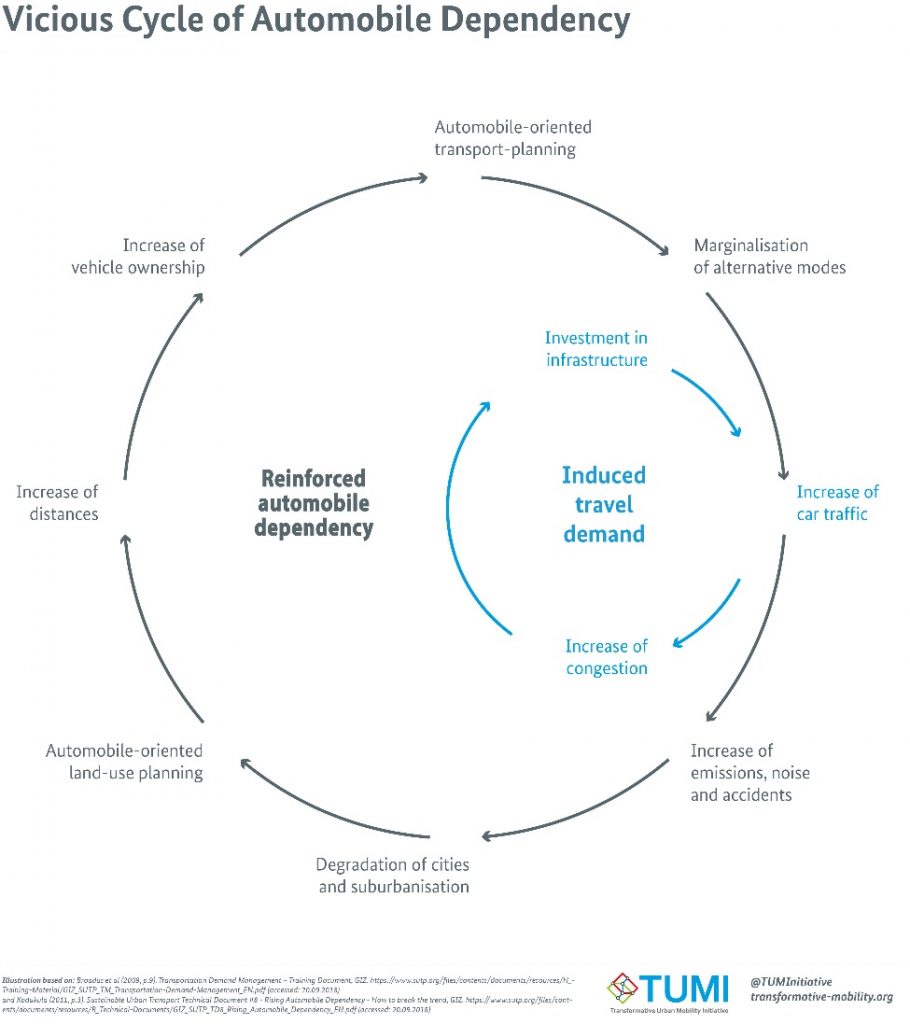

Destination accessibility is often used as a measure to reduce vehicle miles traveled (VMT), but poor accessibility results in high VMT as a consequence of sprawl as shown in Figure 1.5. When mobility and accessibility are considered narrowly, the sprawl cycle ensues, which focuses on auto travel and fails to “sync” activity uses into centers, allowing instead the random expansion of residential and commercial development. As a result, agencies are always playing catch-up – trying to expand investments into outlying areas rather than use investments to reinforce multimodal activity and compact urban growth.

Figure 1.5. The vicious cycle of automobile dependency

Source: Transformative Urban Mobility Initiative, 2019, CC BY-SA 4.0

Multimodal Performance Measures

After the implementation of multimodal transportation planning strategies, a necessary step is to observe and measure the performance of these strategies over time. Transportation performance measures provide indicators of progress toward achieving established goals, objectives, or targets. Different measures for different facilities, modes, or areas can be used. For example, quality or level of service (LOS) is commonly used to evaluate the transportation system and is used to measure automobiles, transit, bicycles, and sidewalks. Potential barriers should also be considered when establishing indicators to measure the success of a system.

There are several indicators that can be used to measure multimodal transportation system performance. Common indicators include those related to the transportation system, health, the economy, land use, and politics. Several of these indicators and some related factors are as follows:

- System indicators

- Ridership, facility utilization rates, and traffic counts

- Completion of multimodal networks

- Health indicators

- Crash rates and fatalities

- Emergency response time

- Public perception of safety

- Economic indicators

- Land values or rents and employment data

- Allocated system funding

- Land use indicators

- Balance of residential and non-residential development

- Political Indicators

- Political buy-in

- Potential government funding

- Political goals, objectives, and policies that support the multimodal transportation system

More information on evaluating system performance, including performance-based planning, performance measures for multimodal plans, modal quality and LOS, and evaluating accessibility is provided in Chapter 8 of this book.

Why is Multimodal Transportation Planning Important?

Modal diversity is particularly important for persons who need or want access to non-motorized transportation options. Litman (2021a) groups these persons into the following categories:

- Children and teenagers who do not possess a driver’s license

- Seniors who do not or should not drive

- Adults unable to drive due to a disability

- Lower-income households burdened by vehicle expenses

- Law-abiding drinkers, and other impaired people

- Community visitors who lack a vehicle or driver’s license

- People who want to walk or bike for enjoyment and health

- Drivers who want to avoid chauffeuring burdens

- Residents who want reduced congestion, accidents, and pollution emissions.

The list of multimodal system users and the mode profiles demonstrate that myriad factors influence a transportation system’s capacity for modal diversity. These factors include socio-demographics, the built environment, attitude toward travel, travel characteristics, and mode choice. Many of these factors will be explored in more detail throughout this book, but to explain the significance of modal diversity, we will begin by addressing mode choice.

Factors people consider when choosing a mode include the convenience of the mode selected, available income and the cost of travel, travel time and reliability, available commuter benefits, commute distance, and life events. Furthermore, people are more inclined to continue to use a mode that they have used for an extended period of time. With the emergence of new and emerging technology such as ride sharing services, mode choice is further expanded. The ways in which innovation is impacting how people travel are still being explored and will be explained later in this book.

Mode choice is influenced by both internal and external factors. Planners, designers, engineers, and policy-makers, through a comprehensive and holistic multimodal planning process, can make multimodal transportation a more appealing choice for those who may otherwise drive alone (Schneider, 2013). This process requires strategies that increase the awareness and availability of various modes, improve safety and security, ensure convenience and affordability, and emphasize the personal, social, and environmental benefits of multimodal transportation. Finally, strategies that modify behavior long enough to generate better habits, such as transitioning from automobile dependence to walking, biking, or transit use, are directly linked to these processes. Although behavior-modifying strategies may be a significant component of multimodal transportation system planning, they have been criticized as being less effective than simply providing safe, efficient, and affordable modal options (Handy, 1996; Schneider, 2013).

*

Key Takeaways

Transportation is a means to ends – it moves people and goods from point A to point B. The way we plan for transportation impacts the quality of the ends – access, mobility, health, safety, the environment, the economy, and socialization/community cohesion. Multimodal transportation planning integrates transportation and land use to ensure the safe efficient movement of all system users and provides a means to more positive ends. Key takeaways from this chapter are:

- Effective multimodal transportation planning is both a transportation and land use activity.

- Diverse mobility options that meet the needs of various system users is the key to ensuring the safe and efficient movement of all system users.

- The traditional concept of “predict and provide” is reactive to, rather than guiding, future growth; offers limited solutions to transportation needs; and induces demand for more driving.

- Contemporary transportation planning should place more emphasis on expanding and reinforcing mode choice.

- Transportation language that is neutral and multimodal ensures positive change for multimodal transportation and ensures clarity when communicating with the public.

- The organization and location of land uses directly affects mobility and the efficiency of all transportation modes.

- Multimodal transportation is supported with a dense and diverse mix of land uses and services on an interconnected street system.

- Modal diversity is important for persons who need or want access to non-motorized transportation options.

- Factors people consider when choosing a mode include the convenience of the mode selected, available income and the cost of travel, travel time and reliability, available commuter benefits, commute distance, and life events.

*

Self Test

*

Glossary

Accessibility: An areawide measure of the ease with which people can move between defined geographic areas to access desired activities and services (e.g., the ability to reach a given location from numerous other locations, or the ability to reach a variety of other locations from a given location).

Activity Center: A compact node of development containing uses and activities which are supportive of and have a functional relationship with the social, economic, and institutional needs of the surrounding area.

Mobility: The ability of people to move between origins and destinations using various modes of transportation.

Multimodal Transportation Planning: The integration of transportation and land use to provide diverse mobility options that meet the needs of various system users.

*

References

FHWA. (n.d.). The transportation planning process briefing book: Key issues for transportation decisionmakers, officials, and staff. Retrieved July 9, 2021, from https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/planning/publications/briefing_book/index.cfm

Florida Department of Transportation: District 5. (2011). State Road 50 multi-modal corridor study: Executive summary. Kittelson and Associates, Inc. https://www.cflroads.com/project-files/359/2020-12-31%20SR%2050%20Final%20Report.pdf

Handy, S. (1996). Methodologies for exploring the link between urban form and travel behavior. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 1(2), 151–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1361-9209(96)00010-7

Kuzmyak, J. R., Walters, J, Bradley, M, and Kockelman, K. (2014). NCHRP report 770: Estimating bicycling and walking for planning and project development: A guidebook. Washington, D.C.: Transportation Research Board of the National Academies.

Levinson, D. (2021, February 28). Fundamentals of transportation. Engineering LibreTexts. https://eng.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Civil_Engineering/Fundamentals_of_Transportation

Litman, T. (2021a). Introduction to multi-modal transportation planning: Principles and practices. https://www.vtpi.org/multimodal_planning.pdf

Litman, T. (2021b). Towards more comprehensive and multi-modal transport evaluation. 27.

Lockwood, I. (2017). Making the case for transportation language reform: Removing bias. ITE Journal. https://tooledesign.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/ite_language_reform-by-ian-lockwood-pdf.pdf

Rodrigue, J.-P. (2020). The geography of transport systems. https://transportgeography.org/

Schneider, R. J. (2013). Theory of routine mode choice decisions: An operational framework to increase sustainable transportation. Transport Policy, 25, 128–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2012.10.007

Transformative Urban Mobility Initiative. (2019). Vicious cycle of automobile dependency. Own work. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vicious_Cycle_of_Automobile_Dependency.png

U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2021). Use of energy for transportation—U.S. energy information administration (EIA). https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/use-of-energy/transportation.php

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2016, October 1). Ports primer: 5.1 goods movement and transportation planning [Overviews and Factsheets]. https://www.epa.gov/community-port-collaboration/ports-primer-51-goods-movement-and-transportation-planning

Weilant, S., Strong, A., & Miller, B. (2019). Incorporating resilience into transportation planning and assessment. https://doi.org/10.7249/RR3038

Williams, K., Claridge, T., & Carroll, A. (2015). Multimodal transportation planning curriculum for urban planning programs (NITC-ED-851). NITC. https://nitc.trec.pdx.edu/research/project/851

Williams, K., & Seggerman, K. (2014). Multimodal transportation best practices and model element. https://www.nctr.usf.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/77954.pdf

Williams, K., Seggerman, K., Pontoriero, D., & McCarville, M. (2010). Mobility review guide. https://www.cutr.usf.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Mobility-Review-Guide-CUTR-Webcast-04.21.11.pdf

The ability of people to move between origins and destinations using various modes of transportation.

An areawide measure of the ease with which people can move between defined geographic areas to access desired activities and services (e.g., the ability to reach a given location from numerous other locations, or the ability to reach a variety of other locations from a given location).

The integration of transportation and land use to provide diverse mobility options that meet the needs of various system users.