17 Case Study #1 – Human Health

Case study #1 – The Farmer’s Flu

Disclaimer: This is a fictitious scenario created for the purposes of microbiome, health, disease, and environmental education. Any names, characters, places and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Part I – Background and Problem

During one week at the end of January of 2019, a high number of flu-like cases have appeared in the small city of Bogart, Iowa which has a population of approximately 50,000 people. 157 individuals were hospitalized over a two-week period, and large proportion included children under the age of 5 years old. Many common symptoms were initially observed in the majority of the patients, however, other less common symptoms manifested in some ill patients after about a week and earlier in those who were immunocompromised and with co-morbidities.

-Common symptoms included:

- fever

- headache

- muscle pain or body aches

- shortness of breath

- vomiting

- diarrhea

- cough

- congestion or runny nose

- fatigue

-Less common symptoms included:

- stiff neck

- lethargy

- chest pain

- swelling of the throat

- severe joint pain

- green, yellow, or bloody mucus production

- facial redness and swelling

Article 1: Respiratory Viral Infection-Induced Microbiome Alterations and Secondary Bacterial Pneumonia

Initial epidemiological data showed that diseased individuals all were at or were in contact with someone who visited the farmer’s market the previous weekend. The market was established more than 20 years ago, and each weekend merchants open their stalls selling everything from pottery, jewelry, and linens to produce, homemade jams, and even livestock. The market is considered to be the staple of town commerce and entertainment, giving Bogart its cozy home-town feel, and even many consumers and merchants come in from the smaller surrounding towns to benefit from the commerce.

Questions:

- What specific pathogens could be responsible for the observed symptoms and why would there be differences in the observed effects in different individuals?

- Which microbiomes may be implicated in this disease and why?

- Do you think this situation is a major public concern? Why or why not?

Attributions:

- Video 1 – Raising temperatures: the immunology of influenza by British Society for Immunology under a Creative Commons Attribution License (reuse allowed)

- Article 1: Respiratory Viral Infection-Induced Microbiome Alterations and Secondary Bacterial Pneumonia by Hanada et al., 2018 under CC BY 4.0 license

- Article 2 – Allergic inflammation alters the lung microbiome and hinders synergistic co-infection with H1N1 influenza virus and Streptococcus pneumoniae in C57BL/6 mice by LeMessurier et al., 2019 under CC BY 4.0 license

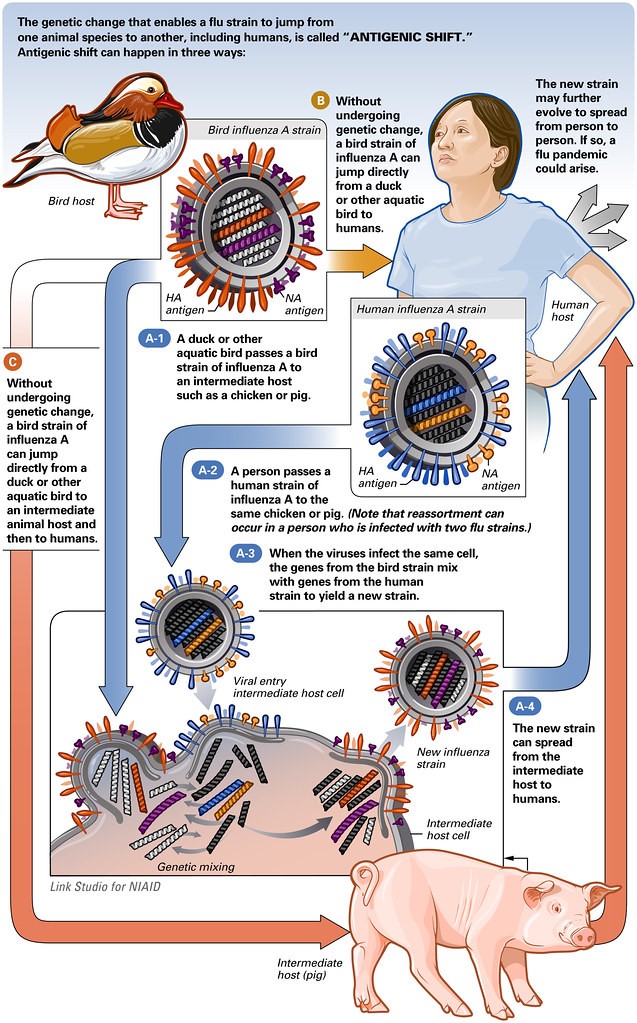

- Figure 1 – Antigenic Shift of the Flu Virus by NIAID licensed under CC BY 2.0 license

Case study #1 – The Farmer’s Flu

Disclaimer: This is a fictitious scenario created for the purposes of microbiome, health, disease, and environmental education. Any names, characters, places and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Part II – Approach, Implementation, Reasoning

Medical personnel took nasopharyngeal (NP) swabs of sick patients for testing. For children and older adults and those who were averse to NP swabs, nasal and throat swabs or aspirate specimens were collected (Flu specimen collection – CDC). Physicians prescribed various antiviral medication; either two doses per day of oral oseltamivir, four oral doses per day of umifenovir, or inhaled zanamivir for 5 days, and for patients in the hospital, one dose of intravenous peramivir or oral baloxavir for one day. They also prescribed prophylactic antimicrobials, including quinolones (moxifloxacin), cephalosporins (ceftriaxone and cefepime), or macrolides (azithromycin), or a glycopeptide (vancomycin). Other over the counter drugs were suggested to treat symptoms like fever and headache. Public health officials advised the community to get the flu vaccine as well.

Over the next few weeks, the number of cases increased and symptoms began to worsen for many. The initial assumption is a seasonal flu outbreak. Interestingly, more cases began to pop up in surrounding rural towns, and many patients were transported to the larger hospitals in the city to be put on ventilators. As mortality rates also began to rise, the CDC declared this situation a flu epidemic.

Article 1 – The respiratory microbiome and susceptibility to influenza virus infection

Article 2 – Secondary Bacterial Infections in Patients With Viral Pneumonia

Article 3 – Patterns in the longitudinal oropharyngeal microbiome evolution related to ventilator-associated pneumonia

Questions:

- What types of laboratory tests and analytical techniques do you think were being conducted? What problems could have arisen with the analysis of the patient’s samples?

- Why do you think both antibacterial and antiviral medication was prescribed? How would you explain the difference between treatments of a viral and a bacterial infection to a patient?

- What reasons or factors could cause a high mortality rate in those infected with the influenza virus?

Attributions:

- Video 1 – Influenza Virus – Viral entry and fusion inhibitor by iCAP Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1 under a Creative Commons Attribution License (reuse allowed)

- Article 1 – The respiratory microbiome and susceptibility to influenza virus infection by Lee et al., 2019 under CC BY 4.0 license

- Article 2 – Secondary Bacterial Infections in Patients With Viral Pneumonia by Manohar et al., 2020 under CC BY 4.0 license

- Article 3 – Patterns in the longitudinal oropharyngeal microbiome evolution related to ventilator-associated pneumonia by Sommerstein et al., 2019 under CC BY 4.0 license

Case study #1 – The Farmer’s Flu

Disclaimer: This is a fictitious scenario created for the purposes of microbiome, health, disease, and environmental education. Any names, characters, places and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Part III – Discussion

After several weeks of patient study and a rising number of mortality and cases, infections were confirmed to be from a mutated variant of influenza A (H1N1; i.e. swine flu). Medical officials believe the high mortality rate and other severe cases may be due to a secondary bacterial infection caused by a pathogen that is resistant to antimicrobials.

Further epidemiological analysis shows that the initial original cases were specifically in individuals who visited the livestock section of the farmer’s market for an extended period of time.

Article 2 – Antimicrobial use and production system shape the fecal, environmental, and slurry resistomes of pig farms

Article 3 – Influence of Pig Farming on the Human Nasal Microbiota: Key Role of Airborne Microbial Communities

***Apologies, the video and audio are a bit glitchy.***

Last line of defense antibiotics, polymixin (colistin) and carbapenems, were prescribed for patients not responding to the initial antibiotics. These patients were also put under quarantine in ICU wards as their symptoms began to worsen, which additionally included abdominal pain, bloody stool, and severe diarrhea that persisted in patients even after being discharged from the hospital.

Questions:

- How do you think antibiotic resistance of the secondary bacterial pathogen came about?

- How could chemotherapy affect various microbiomes and potentially contribute to pathogenesis and other disease symptoms?

- How would you inform the public about this situation, and what measures would you suggest to prevent transmission or recurrence?

Attributions:

- Article 1 – The distribution of microbiomes and resistomes across farm environments in conventional and organic dairy herds in Pennsylvania by Pitta et al., 2020 under CC BY 4.0

- Article 2 – Antimicrobial use and production system shape the fecal, environmental, and slurry resistomes of pig farms by Mencía-Ares et al., 2020 under CC BY 4.0

- Article 3 – Influence of Pig Farming on the Human Nasal Microbiota: Key Role of Airborne Microbial Communities by Kraemer et al., 2018 under CC BY 4.0

- Video 1 – Fact Check: Agriculture and Antibiotic Resistance by Livestock & Poultry Environ. Learning Community under a Creative Commons Attribution License (reuse allowed)

- Article 4 – Incidence, outcome, and risk factors for recurrence of nosocomial Clostridioides difficile infection in adults: A prospective cohort study by Karaoui et al., 2020 under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

- Video 2 – Antibiotics and the Digestive Microbiota | Jean Carlet by World Economic Forum under a Creative Commons Attribution License (reuse allowed)

Case study #1 – The Farmer’s Flu

Disclaimer: This is a fictitious scenario created for the purposes of microbiome, health, disease, and environmental education. Any names, characters, places and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Part IV – Resolution

Research scientists, medical professionals, and epidemiologists finally pieced the ‘Farmer’s Flu’ epidemic puzzle together using next generation sequencing technology and keeping detailed records of observational data.

Two farmers from a nearby rural town contracted the novel swine flu variant. They then brought the pigs to market in Bogart, where the flu spread. However, they not only spread the flu variant, but also a highly contagious antibiotic-resistant strain of Haemophilus influenza type B (Hib). One of the farmers was sick the week prior and therefore immunocompromised which allowed the development of this secondary infection. It is likely that this strain of H. influenza acquired antibiotic resistance via horizontal gene transfer from Haemophilus parasuis, which is commonly found in pigs.

As this respiratory disease was treated with multiple ineffective prophylactic antimicrobial drugs, patients’ resident microbiomes became depleted and allowed for another infection by opportunistic pathogens. In the case of those who were hospitalized, many developed another secondary infection by Clostridioides difficile, resulting in gastrointestinal distress.

After a few months, with the use of both old and new treatment options, outreach to the public with information about the diseases, and proper community compliance, the epidemic came to an end. Bogart resumed as a quiet cozy town, and still holds its locally famed farmer’s market.

Reading 1: H. influenza – CDC – Epidemiology and Vaccine-Preventable Diseases

Article 2 – The Gut-Lung Axis in Health and Respiratory Diseases: A Place for Inter-Organ and Inter-Kingdom Crosstalks

Questions:

- How is the gut microbiome linked with the oral and lung microbiomes? Explain how both of the secondary infections by H. influenza and C. difficile in this case could be related by their respective microbiomes.

- What other diseases, conditions, or treatments have similar multi-microbiome effects?

- What are some examples of novel microbiome diagnostic and treatments that could work to restore the affected microbiomes?

Attributions:

- Article 1 – Basic Characterization of Natural Transformation in a Highly Transformable Haemophilus parasuis Strain SC1401 by Dai et al., 2019 under CC BY 4.0

- Video 1 – Microbiota and Vaccines – Eric Brown by National Human Genome Research Institute under a Creative Commons Attribution Liscence (reuse allowed)

- Article 2 – The Gut-Lung Axis in Health and Respiratory Diseases: A Place for Inter-Organ and Inter-Kingdom Crosstalks by Enaud et al., 2020 under CC BY 4.0

- Article 3 – Translating Lung Microbiome Profiles into the Next-Generation Diagnostic Gold Standard for Pneumonia: a Clinical Investigator’s Perspective by Kitsios, 2018 under CC BY 4.0