12 Branding

Initiative branding

Initiative coordinators should create a name for their course marking initiative in cooperation with the college or university’s marketing department, especially if no larger open and affordable initiative has been named on campus. Preexisting branding of partner units or the institution may influence this decision (e.g., a mascot or slogan that lends itself well to adaptation). The scope of materials the markings will designate can also influence the naming of the marking initiative. For example, coordinators whose initiatives focus on affordability over openness may want to avoid the term “open educational resources (OER)” for their messaging about course markings. Instead, they should consider whether another term will be more recognizable. For example, Kwantlen Polytechnic University used “Zero Textbook Cost,” which can be abbreviated to ZTC, while others have used “No-Cost/Low-Cost,” or “NoLo.”

Labeling markings

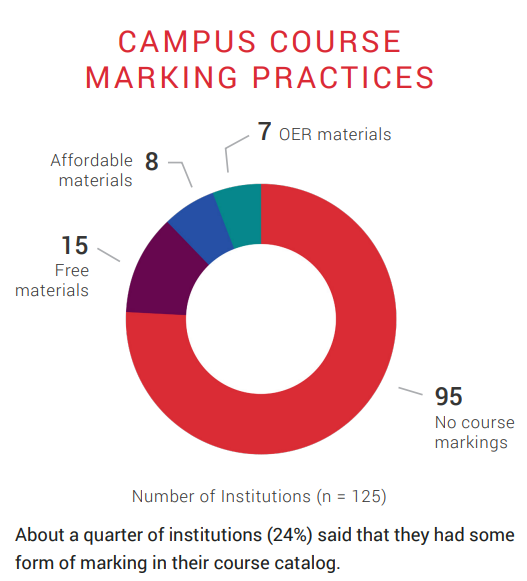

When deciding on which markings to include in a course marking initiative, coordinators should consider what will be appealing and memorable based on their institutional context. The Scholarly Publishing and Research Coalition’s “2018-19 Connect OER Report” found that only 7% of institutions use an OER marking in their schedule of classes or course catalog, in contrast to 8% that mark affordable materials and 15% that mark “free” materials (SPARC 2019a; fig 12.1).

As mentioned in Chapter 7 (Preparing for Implementation), institutions should start their course marking project by determining what open and affordable markings are most appropriate for their students and how each of those markings will be defined for their institution. To help institutions make that decision, this chapter provides an overview of the commonly used terminology for open and affordable course markings, including arguments for and against their usage.

OER

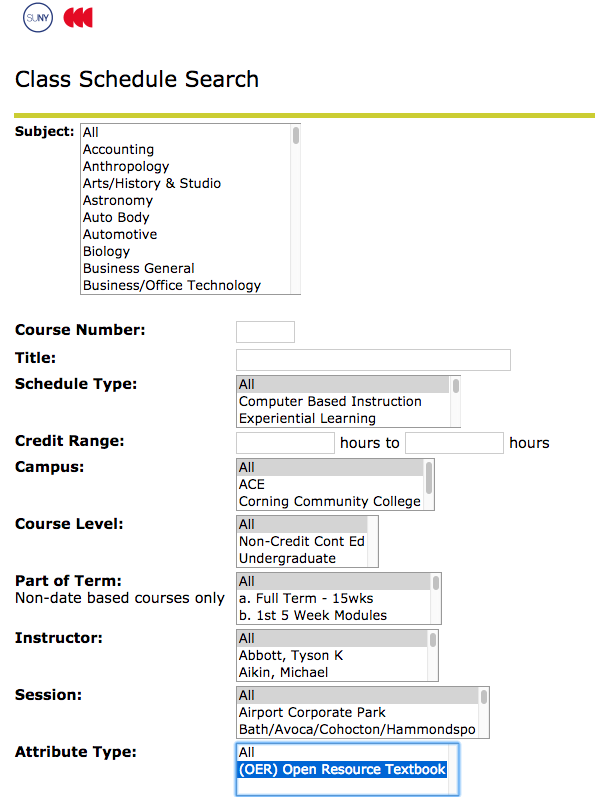

One of the first labels an institution might consider for its course schedule is “OER.” OER refers to educational materials that are openly licensed and free to access online. Optional print copies may be made available for purchase at a low cost. In some states (i.e., Oregon, Texas, and Colorado), the laws requiring open and affordable course markings explicitly ask that institutions label OER. In practice, these labels may use different terms for OER, but most of the open and affordable course marking programs mentioned in this volume recognize OER in some form. In addition, some colleges, like Corning Community College (fig. 12.2), have an explicit explanation of OER in their course schedule.

Opportunities

Having a marking for OER in the course schedule can help spread awareness about OER on campus, and when paired with easy-to-find additional information it can also clear up misconceptions about the differences between OER and other no-cost course content. Most importantly, this marking is useful for institutions that must meet federal requirements to track OER usage. Whether a label for OER is required by legislation or an institution simply wants to demonstrate their OER initiative’s impact by showcasing its reach, including a marking for OER in the course schedule can be beneficial if it is accompanied by reliable data.

Challenges

Although adding OER to the course schedule can help increase awareness and interest in these resources, that process will take time. Some instructors might not know what “OER” means, which makes this marking functionally useless unless and until it is explained (Seaman and Seaman 2017). Even if OER is defined in the marking’s mouseover text, and a key within the course schedule itself, there is no guarantee that users will find and comprehend the information. The use of OER as a marking can increase conflation of open and free resources, particularly when the marking is applied without a vetting or mediation process, which would almost certainly entail additional labor for staff. The concern that the term “OER” is too difficult to comprehend is a valid one, but this concern can be overcome. Luckily, there are other course markings that can be adopted in addition to a course marking for OER to make the differences between “open” and “free” more clear.

No-Cost or Zero Textbook Cost

Some institutions utilize a term other than OER when listing courses that use them in course schedules. For example, many institutions have chosen to use a designation such as “no-cost,” “free,” or “zero textbook cost” for both free copyrighted resources and OER. These markings can be utilized to mark courses with no course material costs whatsoever; no direct textbook costs (though fees may be collected with tuition); or no course material costs aside from equipment and supplies (e.g., calculators or clickers). Regardless of the specifics, institutions applying a no-cost marking should be up-front about what is included in their course materials cost equation and what additional costs might be required in a “no-cost” course. Figure 12.3 is an example of a no-cost icon used by multiple institutions, including Palomar College, Santa Ana College, and Yuba College.

No-cost markings are especially important for institutions with Z-Degree pathways, which use only OER and other free materials in every course needed to complete a specific degree. For institutions with Z-Degrees, no-cost markings can be used to carefully plot out a student’s choices and ensure that they save the most money possible.

Opportunities

Because descriptive, plain-language markings are easy to comprehend, they are the most popular cost-related course markings in use and are present in more than half of the case studies within this volume. Apart from a recognizable message, the no-cost designation broadens what is encompassed to include not only OER but also such materials as library resources and resources already paid for through student fees. The no-cost designation covers the use of free resources when open content does not exist or is inadequate for a particular subject area. It can also promote the importance of other affordability initiatives, such as course reserves and textbook lending programs within libraries.

Challenges

Using a no-cost course marking can make educating the campus community about the markings easier, but it can also make promoting openly licensed resources more difficult (Wiley 2019b). When the conversation on campus is framed solely around cost, faculty and administrators making decisions on behalf of students may think that a non-OER no-cost option and an OER option are the same thing. However, focusing on cost alone ignores the additional freedoms that are afforded through an OER’s open license. Initiatives that focus on no-cost marketing will need to more carefully explain the differences between OER and free-but-not-open content to account for this potential concern.

Low Cost

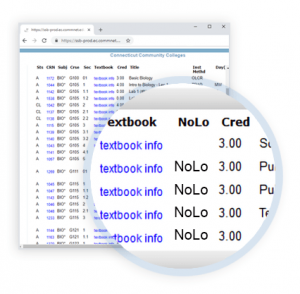

Many institutions have chosen to use a designation such as “low cost” for their course markings initiative, whether stand-alone or in addition to a no-cost marking. These materials may include low-cost publisher resources that are not yet available as OER, a homework platform, or laboratory materials. Often, these materials are defined by a set dollar amount between $25 and $50. This low-cost threshold is determined in various ways. At Maricopa Community College, these numbers are based on feedback from surveys asking students how they define low cost (personal communication with Lisa Young 2019). This number is also sometimes decided by a legislative body. In general, it is best if the institution using a low-cost marking provides explanations of what materials are counted toward the materials cost for a course and how the cost ranking is determined. This is the case at Washington Community and Technical Colleges, who put together a set of standards for delineating whether a course counts as low-cost, based on the pre-tax retail price for course materials, not including tools and supplies (Washington Community and Technical Colleges 2019). The Connecticut State Colleges and Universities system allows students to search for courses that are categorized as “NoLo,” meaning that they qualify as either low-cost ($40 or less) or no-cost (fig. 12.4).

Opportunities

Many institutions (or legislatures) who adopt low-cost markings do so believing this information is beneficial for students. The low-cost designation allows for instructors to assign materials that may be necessary for their course (e.g., online homework platforms or lab manuals) while remaining mindful of high costs and making decisions to keep total course costs under a certain threshold. This designation is particularly useful for courses in the humanities, such as Modern Literature, where required texts are relatively affordable and cannot be replaced by openly licensed alternatives.

Challenges

Focusing on a low-cost designator in place of no-cost and OER designators ignores some of the key benefits of OER for instructors and students. Some OER advocates argue this can cause long-term price increases as publishers shift their strategy to focus on new streams of revenue, such as online homework systems and cost-reduction models like “Inclusive Access” (this model is discussed in the Houston Community College case study). Although it may seem like a simple decision, there are many reasons why focusing on cost savings to the detriment of other benefits could have negative effects on both users of open content and the market surrounding it. In practice, low-cost markings are frequently adopted alongside open or no-cost designations.

Trends in Affordable Course Markings

It is important that institutions keep the opportunities and challenges covered above in mind when branding no- and low-cost course materials in their schedule of classes. Some colleges choose to label only OER in their schedule, while others might provide an OER label as well as a no-cost or low-cost label to acknowledge the various ways in which students can save money. Depending on an institution’s context and their reasons for marking courses, the way in which they approach their course markings and what they are called may differ. Table 12.1 provides a comparative analysis of some of the case studies in Part VII and how they identify their open and affordable course markings.

| Case Study | Marking Used |

| Central Virginia Community College | OER. Defined loosely, OER is not limited to open materials and includes low-cost ($40) or no textbook costs for the course. |

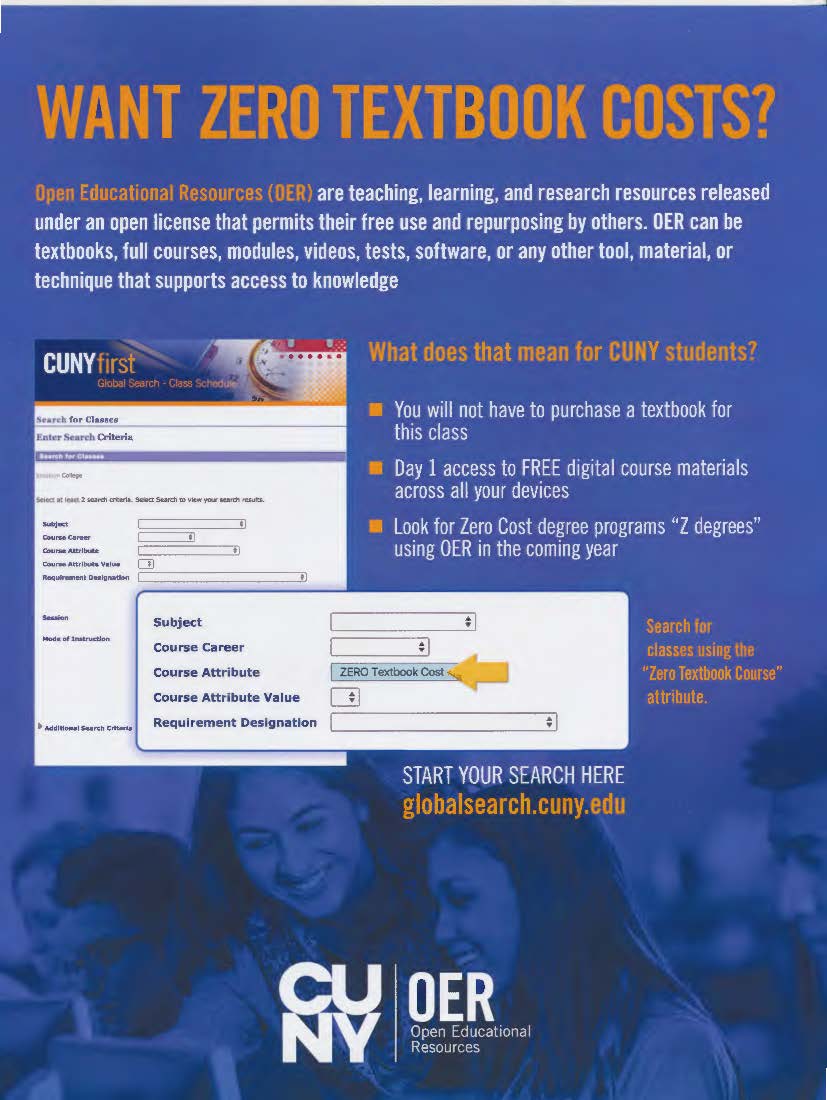

| City University of New York | Zero Textbook Costs. Describes a combination of OER and openly accessible materials and library resources. |

| Houston Community College | Low-Cost Textbooks (LCB) and Zero-Cost Textbooks (ZCB). LCB describes materials costing less that $40. |

| Kansas State University | O icon. Identifies open or alternative resources, including open access textbooks and other high-quality OER, library resources, multimedia resources, and instructor-authored materials. |

| Kwantlen Polytechnic University | Zero Textbook Costs (ZTC). |

| Lower Columbia College | OER and Low-Cost Materials. Low-Cost Materials describes materials costing less than $30. |

| Mt. Hood Community College | Low Cost and No Cost. Low Cost describes materials costing less than $50. |

| Nicolet College | Low Cost and No Cost. Low Cost describes materials costing less than $50. |

| State University of New York | OER. System-wide designation describes “Teaching, learning, and research resources that reside in the public domain or have been released under an intellectual property license that permits repurposing by others.” |

The majority of the case studies highlighted above use a low-cost designation with an upper cost limit in the range of $30 to $50. Of those that adopted an OER designation, only one of the institutions utilized the standard definition of OER, which requires the material to be in the public domain or openly licensed, free, redistributable, and without restrictions on remixing. The other institutions did not utilize the standard definition of OER, including resources with low-cost access and resources bound by traditional copyright restrictions. This may reinforce concerns that vocabulary adopted for course markings can increase conflation of open materials and free or low-cost alternatives that still require permissions or otherwise control access.

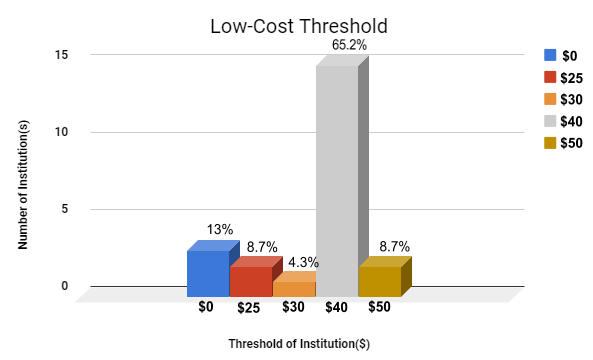

The results from a survey tracking institutions that have implemented course markings (Finkbeiner n.d.) show slightly more robust results. Of the 44 institutions that submitted responses as of September 12, 2019, 23 indicated that they use a low-cost designation and/or a low-cost threshold (Finkbeiner 2019). When asked what threshold was used, the most popular answer was $40 with 15 responses (65.2%). For some respondents, the threshold was equal or less than $40, while others did not include $40 in their cost requirements. Two of the three institutions that selected zero noted the resources would need to be available for free as a digital version in order for resources to receive the low-cost designation. Other responses included $25 (2 responses, or 8.7%), $50 (2 responses, or 8.7%), and $30 (1 response, or 4.3%). Though representing a relatively small sample size, the spreadsheet suggests that $40 is emerging as the preferred threshold. Information about how and why each institution decided on a particular threshold was not collected in the survey.

Icon design

Open and affordable course markings can be implemented in a variety of ways: via text or icon, as part of the course description, or in a separate column of a table layout. If it is possible to include graphics in the course schedule platform, it may be valuable to consider designing a simple icon to mark open and affordable courses. A report for the Oregon Higher Education Coordinating Commission recommends having a recognizable icon (with an explanation where appropriate) for effective branding everywhere students search for classes and course materials. This should incorporate an icon or phrase that is easily understood, not simply “OER” as students don’t always comprehend that designation without explanation (Freed et al. 2018).

Icon design should be an early consideration in the communication and branding process. Institutions may choose to use a designer on staff or hire a contract designer to create the icon. Regardless, an icon’s design should draw on a number of considerations, which are described below. These principles were inspired and informed by Lupton and Cunningham (2014) and Lupton and Phillips (2015).

- Simplicity: the icon should convey meaning simply and concisely. This will ensure that it is easy to understand and remember. Avoid complexity, both in imagery and words (if present).

- Meaning: decide whether the icon should be straightforwardly representational, metaphor-based, or word/acronym-based. This may depend on the name of the open and affordable marking initiative and any larger course materials affordability efforts. If the icon conveys meaning in its design, be sure to incorporate alt text to ensure it meets accessibility requirements.

- Larger branding landscape: consider how the icon will fit in with preexisting branding of the units involved in the open and affordable course marking initiative, course materials affordability efforts at the institutional level, and the larger institution itself. This may impact design elements like shaping and color choices.

- Color: Consider how color choices will appear in different contexts (e.g., print vs. digital, on different devices and screens). Also, consider if meaning or definition will be lost if a viewer has any degree of colorblindness.

- Scalability and flexibility: Keep in mind the variety of contexts in which the icon will be used. It will need to be able to scale effectively to a variety of sizes (from 16 x 16 pixels to larger sizes for posters and other large promotional materials), mediums (digital and print), and background colors. For example, if an icon is too complex, it may be unreadable when scaled very small. Consider creating a variety of versions with different sizes, backdrops, and finishing effects for use in different contexts (e.g., scaling down for inclusion on a class schedule, putting on a website).

Kansas State University offers an example of how an icon for open and affordable course markings can evolve to meet stakeholder needs and satisfy design requirements.

The design is simple and can be scaled to different sizes with ease and without losing meaning. The icon conveys meaning in a straightforward way—the book representing course materials and the “O” denoting “open.” The purple color is in keeping with Kansas State University’s institutional branding and color schemes. And the design is distinct from the normal textbook icon, thus offering a noticeable differentiation. This combination of design elements and decisions produced an icon that was agreeable to all stakeholders and met all of the design needs. See the Kansas State University case study for an in-depth explanation of their design process, including examples of less ideal icons that were not ultimately chosen.

Message Design

When crafting messages, always consider what is the most important information to convey. Messaging is best when it is concise and direct. Initiative coordinators should consider what response they are trying to evoke in their audiences and why the message matters. As a general rule of thumb, there should be only one audience, one goal, and one requested action for each marketing piece. It’s also important to include a point of contact so stakeholders know who to approach for questions, concerns, and feedback.

For example, if students are the primary audience for the materials, explanations about the open and affordable course markings, what they do, and how to find them will be the most important things to emphasize and should be done as simply and concisely as possible. This can be done with a Twitter campaign, small informational cards handed-out during student orientation and in academic advising, and a slogan used on campus. These materials can then point to more detailed webpages for information. A great example of a material targeted toward students is the ZedCred marketing video (Jhangiani 2019a) produced by Kwantlen Polytechnic University in British Columbia.

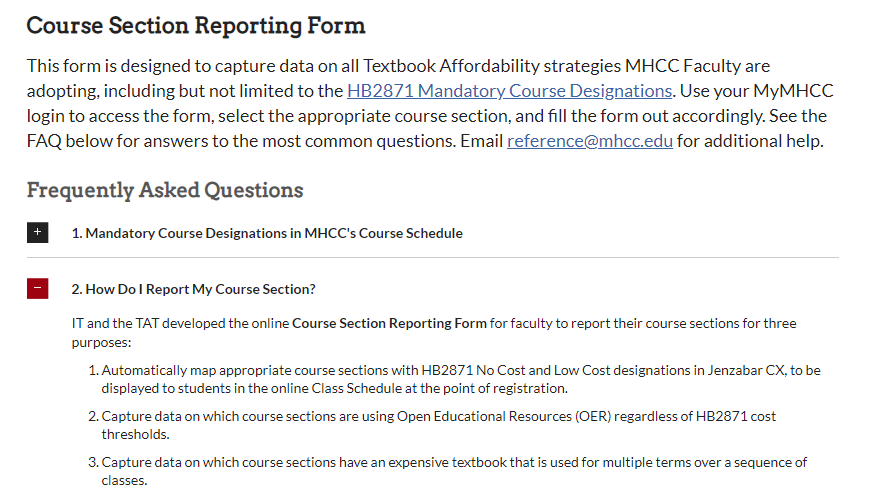

When communicating with faculty and staff members, it can help to focus on the benefits of the open and affordable course markings to students and instructors and how the markings work. For example, instructors will need to know how to report course adoptions, how marking designations are decided, and what types of fees or course material types need to be reported for the new designations. Mt Hood Community College has an excellent resource, the “Course Section Reporting Form and FAQ” (2020a; see fig. 12.7), that their instructors use to better understand how the low-cost course designation process works.

Materials Design

There are many types of marketing materials that can be used to share information about open and affordable course markings on campus. These materials include, but are not limited to: stickers, cards, social media campaigns, slogans, websites, brochures, and flyers (fig. 12.8).

Which material types are ultimately utilized by a campaign will depend on the audiences being targeting. For example, student groups might react better to smaller, more condensed informational materials such as cards or stickers. Conversely, instructors are likely to want more information about the initiative and how they are expected to contribute. Detailed materials are more likely to meet instructors’ needs: brochures, videos, and FAQs.

It is incredibly important to keep branding consistent across different marketing materials. By doing this, initiatives can ensure that individuals across campus will instantly recognize promotional materials as part of the open and affordable course markings initiative. Coordinators should make the central theme of the campaign clear no matter which audience individual marketing materials target.

Once materials have been developed, the next step is dissemination. Depending on the type of material and its goal (e.g., education, announcement, explanation), marketing materials may be disseminated at multiple points in the initiative’s development and implementation.

Free teaching and learning materials that are licensed to allow for revision and reuse.

Also called attributes, designations, tags, flags, labels: specific, searchable attributes or designations that are applied to courses, allowing students to quickly identify important information to aid in their decision making and allow them to efficiently plan their academic careers. Course markings may include letters, numbers, graphic symbols, or colors and can designate any information about a course, including service learning status, additional costs, course sequencing requirements, and whether the course fulfills specific general education requirements.

Courses that do not require students to spend money for textbooks. May be achieved through the use of OER, library-licensed content, or other free resources.

Also called Course Schedule or Schedule of Courses: a college or university’s listing of courses to be offered each semester or quarter, which includes details on class time, prerequisites, instructor of record, and other information; it is updated for each academic period.

Also called Course Timetable or Course Schedule Platform: a college or university’s exhaustive listing of courses and programs currently and historically offered, including course titles and descriptions; course catalogs may also contain information about an institution's policies and procedures.

Also called Zed Cred: a degree, certificate, or curriculum path that has completely adopted free or zero-cost course materials so that as students progress through the degree they do not pay for course materials. All courses within the degree program must commit to zero-costs in order for the degree to be designated a Z-Degree.

A marketing term used to describe an agreement between textbook publishers and professors/institutions that allows all students enrolled in a specific course to be automatically charged for course materials through institutional fees. In the United States, organizations are legally required to provide students with options to opt-out of automatic purchasing programs. Multiple lawsuits have been filed against publishers and bookstores over such programs, including a class-action lawsuit filed in April 2020 by FeganScott on behalf of college students against Cengage Learning, McGraw Hill, Pearson Education, Follett Higher Education Group, and Barnes & Noble College Bookseller.