4 Students

Open and affordable course markings are grounded in the idea of transparently communicating course material costs to students so they can make informed decisions when enrolling in classes. Enabling student agency is an important step in increasing the potential for students to succeed in their academic and professional careers. This chapter explores the role of student agency in higher education and opportunities for involving students in course marking initiatives.

| Context | The main user group of any course marking endeavor as they employ the open and affordable course marking system throughout their registration process. Use course markings to help make educated decisions about which classes to enroll in and the potential financial impact of those classes’ course materials. |

| Opportunities | Students can assist with building more meaningful and effective markings via beta testing and focus groups. Student interest may also help with getting other stakeholders on board. |

| Challenges | Students may not be aware of the new markings or have the time or desire to explore for additional information when focusing on registration, which may be a stressful time. Outreach is especially important to ensure students are aware of the new markings, what they mean, and how to use them. They also may not be aware of OER or how to access the materials, so education about the materials themselves should be done in tandem. |

| Noteworthy | As the main beneficiary of any course marking initiative, students may be able to rally support for course marking initiatives and OER generally in ways that faculty and staff cannot. Engaging students in discussions about course marking can be a useful entry for having more extensive conversations with them about course material costs and the benefits of OER. |

Student Agency

“Agency,” broadly defined, relates to “the socioculturally mediated capacity to act” (Ahearn 2001). Literature on student agency in education tends to focus on agency as empowerment and choice in classroom contexts, specifically as it relates to the role students play in their own learning. For example, Lindgren and McDaniel define agency as “the power of the individual to choose what happens next” and discuss it in the context of a nonlinear pathway through an online learning environment (2012). However, George Kuh and colleagues extend students’ “responsibility for their own learning” beyond the classroom in Student Success in College, including an example from Evergreen State College of students contributing to the development of courses and program themes by offering feedback on curricular proposals posted to public spaces (2005, 167-68). Student advocates also cite agency as a benefit of open educational resources (OER), pointing to the flexibility students frequently experience with OER in making format and access decisions in contrast with the increasing rigidity of the commercial resource market.

For the purposes of this book, the concept of agency also extends to the capacity of students to make informed enrollment decisions. Most institutions require students to take specific numbers of credits and types of courses to meet general education, major, and program-specific requirements in order to graduate. Factors such as complex course sequencing, prerequisites, and the number and frequency of course offerings can make navigating these requirements difficult, even for the most determined and organized student. Academic advisers, registrars, and other student affairs professionals create tools and use student information systems (SIS) or other products to compile relevant information to simplify the process for students.

Course markings support students in planning their daily schedules by allowing them to filter by the mode of delivery (e.g., face-to-face, hybrid, online), instructor of record, campus location, course title, class times and dates, and academic session. The ready availability of this information allows students to find courses that meet major, program, or graduation requirements. Some course markings indicate that courses meet specific requirements, such as prerequisites or corequisites, honors, capstone, writing intensive, oral communication, research intensive, diversity, or service learning courses. Incorporating pricing information, or filters for discovering courses that use open or affordable course materials, furthers student agency by enabling course-level decision-making that accounts for actual costs, individual budgets, and financial need.

Student Outreach

As the main beneficiary of open and affordable course marking initiatives, students may be involved in the call for implementing such markings on campus. According to a 2018 report for the Oregon Higher Education Coordinating Commission, over 60% of the approximately 10,000 university and community college students surveyed noted interest in course designations for OER (Freed et al. 2018). At some schools, for example, Kansas State University, students may even lead the request for open and affordable markings and may need support from other stakeholders to operationalize their ideas.

The Oregon report further reveals that most students gained awareness of open and affordable resources through their instructor. However, it notes that some instructors do not post course lists prior to the registration deadlines (Freed et al. 2018). The report recommends several practices to increase student awareness, many of which center on marketing and communication to engage this stakeholder group. For example, the report suggests having a recognizable icon (with explanation where appropriate) for effective branding everywhere students search for classes and course materials. This should incorporate an icon or phrase that is easily understood, not simply “OER,” because students don’t always comprehend that designation without explanation (Freed et al. 2018). Other considerations are explored in Section IV (Branding and Communication).

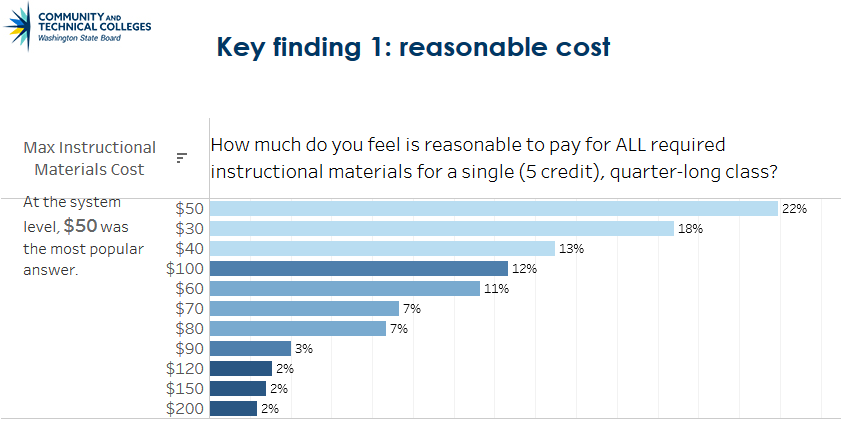

Even if other stakeholders are leading the development of open and affordable course markings, including students in the discussion is still fundamental. Because course marking allows students to search, sort, and limit each semester, quarter, or term’s listing of courses based on a particular marking, student input on the marking—as well as general system features—is integral. Once student stakeholders are more systematically involved in the course marking process, they can also provide feedback on the needs and concerns of the student body regarding changes intended to benefit them. One key area for student involvement is in setting cost thresholds for markings labeled as low cost or affordable, as only students can speak to what these terms mean to them. A survey of over 10,000 students at 34 colleges in the Washington Community and Technical College system (fig. 4.1) showed that $50 or less was the most common choice (22%) as a “reasonable” cost to pay for all required materials in a single class. This was followed by $30 (18%) and $40 (13%). It is worth noting, however, that students did not have the option to select a value lower than $30.

Student organizations

Advocates frequently turn to student governments when seeking student leadership and feedback on OER initiatives. Student government representatives are elected by the student body and can have an important voice in shaping policy and practices on college and university campuses. These representatives are typically tasked with listening to and representing the student body, serving as an appointed member for other campus organizations or committees, and fostering engagement and connection between students and the institution. Many university systems also ask student government representatives to serve on system-wide advisory councils, where they can be powerful ambassadors for open and affordable resource initiatives more broadly. There are numerous examples of students promoting, funding, and rewarding use of OER, as well a growing number of guides to help shape student involvement. For example, a Student Government Toolkit on textbook affordability published by the Open Textbook Alliance advises students on running a textbook campaign, advocating for policy changes, and rallying support in various contexts (2016). Though the resource does not discuss course markings specifically, many of the recommendations apply to conversations about price transparency during registration. The OER Student Toolkit published by BCcampus explores many of the same themes in a Canadian context (Munro, Omassi, and Yano 2016).

Additionally, student governments and other student organizations can be effective change agents with access to policy makers and influence on proposed legislation, particularly at the state level. For example, the Maryland Public Interest Research Group has a student funded and directed chapter at the University of Maryland College Park that provided testimony in early 2020 in support of Maryland House Bill 318. The bill proposed that all institutions in the University System of Maryland “develop a method to clearly and conspicuously show students in the online course catalog which courses use free digital materials” (Cailyn Nagle, email to editor, February 11, 2020). The testimony presented the story of a student whose graduation date was delayed and debt increased due to the cost of course materials; it argues for a future that is free of financial barriers that can negatively impact student success and the related need to provide clear and comprehensive cost information to students at the time they register for classes.

Also called attributes, designations, tags, flags, labels: specific, searchable attributes or designations that are applied to courses, allowing students to quickly identify important information to aid in their decision making and allow them to efficiently plan their academic careers. Course markings may include letters, numbers, graphic symbols, or colors and can designate any information about a course, including service learning status, additional costs, course sequencing requirements, and whether the course fulfills specific general education requirements.

Free teaching and learning materials that are licensed to allow for revision and reuse.

Also called Registration System, Course Timetable Software or Course Schedule Platform: a web-based application designed to aggregate key information about students, including demographic information, contact information, registration status, degree progression, grades, and other information. Some SISs assist students with enrollment, financial aid processes, and final payment for courses.