26 Becoming a Public Historian

A public historian is someone who makes historical knowledge available to the general public. The historian may be a trained academic historian, a person with specialized training in the craft of public history, or an avocational historian who shares their knowledge. Each type has its own advantages and limitations.

Academically trained historians: These public historians can be confident that they are well-trained in how to make meaning out of historical evidence, often by applying theoretical frameworks primarily understood by others with similar advanced training. That sentence contains most of their strengths and weaknesses for doing public history. The public is happy to see pieces of historical evidence-objects, photographs, and documents. The public is less happy with theories, jargon or anything else that makes them feel unwelcome.

The academically trained public historian should change the way they communicate information about history. Use accessible language and appeal to a wide variety of interests and levels of dedication among learners.

The typical trained public historian receives their undergraduate and/or graduate degree in public history or museum studies. They should be well prepared to communicate history to the public. They may not have as much training in sophisticated thinking about history. The public may not like theories but their learning experience can be richer if the message is crafted by someone with a deep understanding of historiography. A good researcher can quickly amass enough understanding of any particular historic event or issue to build a credible public history presentation. A lack of deep understanding could, however make that presentation a bit flat, or superficial. Also, the public will only forgive a mistake, or a demonstrated lack of detailed knowledge, if the historian is ready to learn alongside them.

The trained public historian needs to cultivate a passion for some particular areas of history and to pursue understanding of sophisticated historiography.

The amateur historian enjoys comfortable membership in the public that forms the audience of public history, and may have the easiest time reaching the audience. Such a historian generally studies a limited range of subjects in which they have a passionate interest. They do this in their leisure time while pursuing some other career that may not relate to history. They may have no formal history training beyond high school learning or undergraduate survey courses. If they are personable, their passion for their subject shines through to engage audiences. Their limitations are also born of that passion. They may focus on intense knowledge of objects and facts and assume the audience wants to learn absolutely every detail. They may also fail to give an overall framework into which the learner can place these discrete facts in order to understand them—that is, fail to give context. Passion can produce giant exhibits, long, exhausting writings, and two-hour lectures.

The amateur historian must harness their passion and give the learner the opportunity to take in small or large servings of the historian’s wealth of knowledge.

Every public historian needs to do ALL of the things in italics and is prone to all of the mistakes.

Public History’s Audience

The audience for public history is, ideally, everyone. We all know the popular arguments for the value of studying history: learn about the past so as to avoid repeating old mistakes; you must study the origin and progress of your family, city, nation, political group, ethnic or racial group, profession or philosophy, in order to understand yourself; study the history of groups to which you do not belong, so as to better understand the world. Good public history accomplishes such valuable goals.

Unlike the audience for academic history, the casual learner may not be drawn by intense interest and may have absolutely no basis of existing knowledge. Even worse, they may have inaccurate existing knowledge that they resist questioning.

The actually resistant learner is the hardest of all. Think of the person whose family dragged them to your museum when they had other plans. Think of students assigned to do your fun online history tutorial who do not think history can be fun. Meet each learner on their own terms and try to respond to their interest level. Take failure in stride and revel in even a tiny victory of sparked interest.

The number one job of the public historian—Interpretation

Public history is all, ultimately, interpretation. It is the act of transforming the raw knowledge from primary sources and the complex conclusions produced by academic inquiry into accessible presentations. Difficult, but worth the struggle.

A formalized understanding of the craft of interpretation was made available in 1957. Working with the National Park Service, Freeman Tilden wrote Interpreting Our Heritage as a guide for those who led tours in national parks. His six principals of interpretation were designed for use on tours of the natural world and discussions of larger environmental issues. They work equally well for a historic artifact or document. The constant evolution of the practice of public history has never rendered his basic ideas obsolete. His short book is a quick read and highly recommended.

Here is a list of suggestions for good interpretation:

- Creating interpretation that is accessible does not mean “dumbing down” sophisticated ideas. It is much more difficult than that! It involves careful use of familiar language and skilled use of images and objects to form a message that people with an amateur interest in history can find helpful and intriguing.

- Public history meets learners where they are. A skilled presentation serves as an introduction for those who know nothing about the subject, and provides new information for those already invested in the subject.

- Learners may arrive expecting to be given facts. That would be poor interpretation. Better they leave without a single new fact in their head but with an experience of questioning, of critical thinking, of wanting to know more. Tilden said, “The chief aim of interpretation is not instruction, but provocation.” What do you think a learner remembers longest-a date in history, or the controversy over the meaning of whatever happened on that date?

- Interpretation must be geared to all possible learners, of every age, education level, background or religion, and great efforts should be made to properly include groups previously excluded from discussions of history. Good interpretation is for everybody.

- It is impossible to create interpretation that works equally well for everybody. This dichotomy is for the public historian to resolve with creativity, flexibility and love. (It is rather similar to the problem caused by these two rules of exhibit design: Labels should be brief so they will be read. Labels should be full of information so they are informative and provocative. Good luck with that one!)

- Tilden also said interpretation is an art, and a process. Doing it well takes practice, mastering an art. The idea of process can inform the crafting of any individual interpretive effort, that is, its structure represents a process of introducing the topic and moving through stages of increasing information and active evaluation that includes the learner. One hopes that each interpretive act is but one part of a larger intellectual journey for the learner. Leave them wanting more.

- Interpretation must be true. That sounds obvious but gives rise to so many questions. Is an exhibit offering true interpretation if one of the artifacts is a reproduction? Maybe, maybe not. If you simplify a map of seventeenth-century Europe, de-emphasizing some of the less active countries, is that making the political geography of the time accessible or is it falsification? Probably both. If your audience is bored and drifting, should you spice up your presentation with an amusing anecdote of questionable veracity? That would be tempting, but not good public history, despite the advice in item 7.

- Learners are not looking for an intense boot camp of study followed by a grueling examination. The public historian does not give grades. The learner can leave in the middle if they wish. Like any purveyor of leisure, you must attract and hold their attention. Humor can help, even bad jokes. Horror can help. Few visitors can ignore a display of a Ku Klux Klan robe. They become like drivers entranced by a highway accident. Popular culture references work sometimes, if carefully targeted and explained. Interpretation is a conversation, a performance, a seduction.

History Museums

History museums may be the first place aspiring public historians consider working. They are also the first choice of potential learners. Authors Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen conducted a poll of 1,500 Americans, asking about their relationship to history, and published the results in The Presence of the Past: Popular Uses of History in American Life in 1998. Museums were the most trusted source of information, far ahead of respondents’ history teachers or even their own grandparents.

The earliest museums in the United States presented collections of interesting or exotic objects. They did not strictly adhere to divisions of subject matter, with separate museums for history or science. They lacked even the most rudimentary interpretation

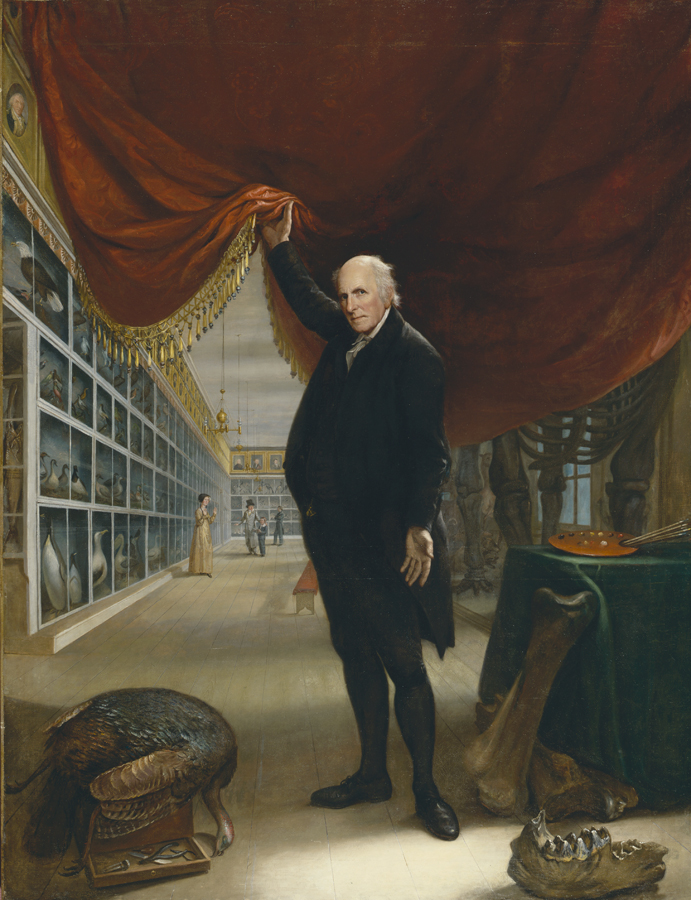

An excellent example of the early museum was created by Charles Wilson Peale (1741-1827) in Philadelphia. Peale was an artist who captured the likenesses of many leaders of the American Revolution. His townhouse included a large studio space, which became the first museum gallery, opening in 1786.

Peale became a collector, the avocation of many early museum builders. Studio visitors admired his displayed objects, thus inspiring the museum. He mostly collected natural history specimens. He displayed bones, including a Mastodon skeleton, and taxidermied specimens of animals, both strange and familiar. He also displayed his own portraits of inspirational American heroes and some Revolutionary War relics. As a compatriot of Benjamin Franklin, it is not surprising that he included examples of recent inventions. He created a large format “cabinet of curiosities,” the term for a domestic display of objects by an amateur collector.

His self-portrait titled “The Artist in His Museum,” depicts the tasteful arrangement of his collection when it was displayed at Independence Hall. We see him at age 81, in 1822, as he lifts the curtain to reveal the secrets of the world. Beyond the curtain we see animal specimens arranged according to the fairly new idea of taxonomy of living things, so that the birds are grouped together. Above are his American hero portraits. Clearly there was an order to the display, and that is a key first step toward providing the viewer with helpful interpretation. But there was little to no signage (or live gallery guides to answer question) to explain the objects, their origin, arrangement and why they merited inclusion. The well-dressed visitors we see in the background were left to observe without direction, unless the collector himself happened along to chat.

Everything has changed since then. Museums small and large proliferated and refined their practices. The main change was away from objects valued mostly for the thrill of possessing that which was rare or exotic or nostalgic toward using them to gain larger historic knowledge. The early collectors, often referred to by the slightly pejorative term “antiquarians,” did not always do that. Often their interest was limited to information about the object’s origin story, including who made it and where, what materials were used, what style might its decoration represent; and its rarity. All of those are good starting points for teaching, but not whole story.

Museums evolved, increasingly presenting the object’s role in larger historical trends. The artifacts themselves were arranged in thematic groupings, to add understanding of their connections. Dioramas and room settings were created to give a more tangible feel of historic environments and how collected objects fit into them. Historic house museums took this method further. Gallery rooms could also group artifacts and their accompanying information by time period, association with specific groups of people, or stages of technological production. Labels and signage explained what the visitor was viewing.

This is not to suggest that museums achieved perfection. Racism and ethnocentrism haunted curatorial decisions, even in exhibits about foreign cultures and people of color. Great men dominated, with occasional cameo appearances by supporting women like Betsy Ross. Elitism was rampant. Displays of domestic objects and room presented the lives of the wealthy, not the everyday environments of other social groups.

The initial audiences for museums were expected to be limited to educated members of the upper social classes, like the people Peale painted visiting his museum. Other people might be dismissed as unable to profit from the knowledge made available in museums. By the Victorian era and into the twentieth century, this thinking changed. Those who were often termed the “common man” were seen as good candidates for visiting a museum. Once there, they would learn from carefully curated presentations of patriotic interpretation, designed to reinforce reverence for the existing social and political systems. Immigrant visitors could learn how to think like Americans. Poorer Americans could embrace middle-class values and norms. Children would be directed to an unwaveringly positive view of their heritage and nation.

This sort of practice reached new heights during World War II and the Cold War era. Museums helped remind soldiers going to Europe and post-war civilians of the reasons to support national initiatives. 1976 may have been the last big hurrah for those ideas in museums. The Bicentennial inspired the creation of endless small local history museums and special exhibits in established ones.

This curatorial tradition of telling visitors what they should think and what they should learn likely contributed to the later backlash against curatorial authority. So did the perceived curatorial focus on collecting as the major purpose of the museum, with education given less respect. The high point of the backlash was the 2010 publication of The Participatory Museum by Nina Simon, which is available to read free online. This began a conversation within the museum community about the importance of making the museum’s wealth of information available to all visitors in a spirit of discussion and equality. The ongoing experiment is producing strategies for balancing the value of collections and meaningful education with equal regard for both.

Advanced training in history is valuable, and often required, for any position in a history museum. The staff who most actively use the skills of the historian are in the education and curatorial departments. Keep in mind the vast range of museum sizes. Some have only one full-time employee who does almost everything. Some have hundreds of people.

Educators share the museum’s information with everybody they possibly can. Their methods can include classes for adults or children, lectures and book discussions, tours of the museum, presentations in schools, designing activities for specialized children’s areas within the museum, and offering educational crafts and games during special events. They plan and oversee field trips. This requires logistical expertise and customer service ability, as well as knowledge of curriculum and local education standards so that the field trip activities meet the needs of the schools. Educators take part in exhibit creation and all events and interpretive planning in the museum.

The curatorial department is responsible for assembling, maintaining and understanding the museum’s collection of historic materials. They use the collection to create exhibits for their museum, for travel to other museums, and online. They may produce other informative offerings, such as videos or publications. They will almost certainly be asked to provide tours of the museum collection, discuss interesting collection pieces online, and work with students. They also make the collection available for scholarly study.

In a small museum, one curator may be both the historian and the person who cares physically for the collection. Ideally a separate collections manager is responsible for all aspects of collection care. Physical care ranges from dusting to hiring professions to restore an artifact. The collections manager knows what and where everything is, as well as how it came to the collection, and if it is sturdy or on the verge of disintegration. They oversee the safe storage, handling and exhibit use of artifacts. In a very large staff there may be positions for archivists, specialized curators, conservators (trained in artifact repair), photographers and exhibit builders.

A public historian who does well may become the director of the museum. If you have this opportunity, do not let the financial spreadsheets and endless courting of donors make you forget that you are a historian.

Other Career Options in Public History

Careers outside of the museum also involve various ways of communicating your understanding of history to those seeking to increase theirs. Where museum work offers the chance to work with historic objects and documents and to craft and carry out exhibits and instructive interactions with the public, some of these alternatives allow you to focus more on one of those areas.

Publishing

The public historian’s thoughtful, accessible interpretation of history can take effective form as writing. Of course, we are past the time “publishing” only referred to printed material like books and magazines, but they are not dead yet and so merit consideration.

Written public history is less burdened with the need to address reluctant learners. Except for student assignments, the disinterested will never be part in your audience! All the goals of interpretation apply to writing. It must be authentic, engaging, welcoming, overtly informative and sneakily more than the learner expected. Language is important and visuals are highly recommended.

Other roles including editing, developing new authors and fields, and promoting books allow the lucky job candidate to work with many historical subjects while enjoying regular employment and benefits. Authors are more likely to be self-employed, though opportunities exist within history organizations that do publication.

We now have so many options beyond books. Technology and creative ways to use it offer constant opportunities to interpret for the connected public. There is little point in discussing specific current technological products—as they will soon change. The wonders of new tools should never overshadow the rules of good interpretation. The field has left behind the days when digital methods of communication were suspect. All acts of interpretation are judged by the same standards.

Fiction is controversial. Novels and films featuring a dramatic or humorous fictional tale set into an (hopefully) accurate historic setting are a complicated issue. The learner, who may think they are casually relaxing with a film or an historical romance, is also studying the past. What an opportunity for the public historian—you have their willing attention! Unfortunately, the most memorable parts tend to be the fights, love scenes and jokes, rather than the background of historical events like political differences and the failures of business. Consider the example of the 1997 movie, Titanic. Most viewers remember the nude drawing scene. Many learned a bit about the strict divisions of social class in 1912, since that idea appeared repeatedly and forcefully. Far fewer likely picked up on the hints that the ship’s owners rushed it into use and ignored safety concerns.

Whatever the limitation of fictional history authorship, serving as an expert advisor on such productions is a legitimate role for a public historian. Such a consultant reviews proposed clothing, furnishings and backgrounds for a film, insuring that these visual elements are correct. The consultant may be able to address language mistakes, such as having a character say “O.K.” before its period of common use. Like all consulting jobs, this requires prior experience to establish credentials.

Cultural Heritage Preservation and Historic Preservation

The more recognized field of historic preservation, in which buildings and landscapes are saved and maintained, is actually a sub-field of cultural heritage preservation. The overall goal of that is to selectively and effectively identify aspects of human culture that should be kept alive and made available to the public for education, celebration and recreation.

Historic preservation in the United States is generally thought to have begun with activist women who formed the Mount Vernon Ladies Association in 1853 to save George Washington’s iconic house. They saw the house as a living symbol of the ideals of the American Revolution, practically a shrine. The ladies learned lessons through hard experience that new preservationists still face. They had to find the means of acquiring ownership, establish an efficient governing organization, fundraise endlessly, and decide how best to maintain the building so that it authentically represents what is termed the “period of significance.” For Mount Vernon that is the lifetime of the hero. Their efforts were overtly directed at inculcating patriotism. They even hoped the structure could turn hearts away from sectional division and prevent the impending Civil War. The house could not do that, but its emotional association with General Washington did keep it safe from Union soldiers who destroyed other houses in their path.

Modern preservation goes far beyond sanctifying the homes of great men-though there is value in those places. Preservation efforts are now directed at saving places representing all kinds of people, as well as cultural trends such as the history of musical genres or theater. Social history points to many sites worth saving, as can all areas of historical inquiry. Efforts have also moved beyond the protection of individual buildings to protecting neighborhoods, urban streetscapes, and rural and agricultural landscapes.

Where can the trained historian find work in this field? Every preservation effort is based on research into the location’s past. The resulting body of knowledge is used in fundraising efforts, public policy decisions and winning citizen support. All are needed to begin the process of preservation. This information guides the physical treatment of the property once preservation begins. For instance, it informs decisions about what parts of the building or landscape should stay because they authentically represent the location’s past, and which should be removed because they do not. Such parts could be as small as a hinge or as big as an orchard or barn.

Private firms employ historians to do such research for clients, as do government entities at all levels. They navigate complex issues of legal limits and official policy, as well as economic interest and public sentiment.

At the federal level, historians work to guide policy and practice in the National Parks Service and in the offices of the Secretary of the Interior, which sets standards for appropriate preservation and maintains the National Register of Historic Places. At the municipal and county level, employees oversee the proper implementation of preservation work and the designation of significant places.

Each state has an affiliate historic preservation office to identify and protect important sites. They work for the state government to properly implement national standards and help local individuals and groups engage in responsible preservation.

In Texas, this office is part of the Texas Historical Commission. They also operate historic sites at houses, cemeteries and agricultural grounds for educating visitors. They authorize and create official historic markers that tell passers-by the significance of the place where they are standing. In their public work they cross over from the smaller area of historic preservation to larger aspects of cultural heritage preservation.

This large preservation field identifies, saves and disseminates information about all aspects of all relevant cultures. Those include not only buildings and smaller objects of all types, but intangible artifacts like folk songs and stories, religious rituals, family celebratory practices, or anything else that tells how a particular people experienced and explained the world. Some preservation organizations and government agencies employ historians to gather material and make it available, but much work in this area may be individual efforts involving little immediate financial gain. Such study can inform publications of all types as well as museum work.

Corporate and Governmental History

Many corporations and governmental agencies employ historians and archivists to maintain the entity’s history. Their primary goal in doing this is to insure smooth current operations by giving staff members easy access to information about organizational history. The historian is expected to have the most thorough knowledge of the organization possible, and know where to find the answer to every question. This type of position may therefore be focused on information classification, storage and retrieval.

There may still be some opportunities to engage in interpretation to the public. The corporate or departmental historian may be charged with overseeing content about the organization’s history for their website, as well as other digital outreach efforts. They could be called upon for archival images or stories for use in advertising or public relations. They might even be able to assemble a more detailed publication about the history of the organization.

One Dallas-Fort Worth example is cosmetic company Mary Kay. They have long maintained an internal historian and a collection of both archival material and objects. This collection is shown in a museum space in the company’s world headquarters in Addison, Texas. The collection of past products and packaging can be referenced for current product development. The record of the company’s history of working with a national, and now international, army of individual sellers is also valuable. They use it to recruit and retain these workers. They promote the history of the company and its founder, Mary Kay Ash, as offering women empowerment and self-sufficiency.

As this one example may suggest, an internally employed historian in such a place may be limited in their historic messaging. As an employee, they may be expected to toe the party line. Every organization likely has unflattering aspects in their past that a good historian would want to explore, but might not be allowed to pursue. Consider this before taking either a regular position or a consulting assignment. Also weigh the possibility of encouraging a more transparent and accurate historical interpretation. You might succeed!

Archives and Libraries

Each of these institutions requires specialized training in their practices for collecting and organizing books and documents and other types of texts. Subject knowledge is a definite plus for recognizing the potential uses each resource holds for historical study. Skill in interpretation supports the other mission function of such institutions: connecting information seekers with the right resources and helping them make full use of them. As the temporary research assistant for each visitor, the archivist or librarian can explore new knowledge on so many subjects while helping people learn how to research, to think critically, and to synthesize discrete facts into useful historical insights.

Recommended resources:

Start online with these two organizations. Both offer free information, student memberships, hold yearly conferences and publish journals. The first is slightly more oriented to the practice of public history across all fields. The second tends to focus more on museum issues.

- The National Council on Public History

- American Association for State and Local History

- The OAH serve all practitioners of history.

- Organization of American Historians

- For insight into the practice of public history in Texas:

- The Texas Association of Museums

- The Texas Historical Commission