4.2 Motivation: Just do

Introductory psychology textbooks commonly define motivation as an internal psychological state that serves to activate behavior and drive them toward meeting a particular goal or need (Huitt, 2001). Motivation is inferred by others when they observe overt and persistent behaviors that are linked to fulfilling some sort of need or action steps toward a goal. Dembo and Seli (2008) explain that the choices that students make (e.g., to study or not to study), the level of engagement in academic tasks (e.g., note taking, preparation for class, use of learning strategies), and finally, the persistence and effort (e.g., working even when a task is considered difficult or boring) directed toward academics are key behavioral indicators of a student’s level of motivation toward academics.

Thought Question

Does your behavior show that you are motivated to go to college?

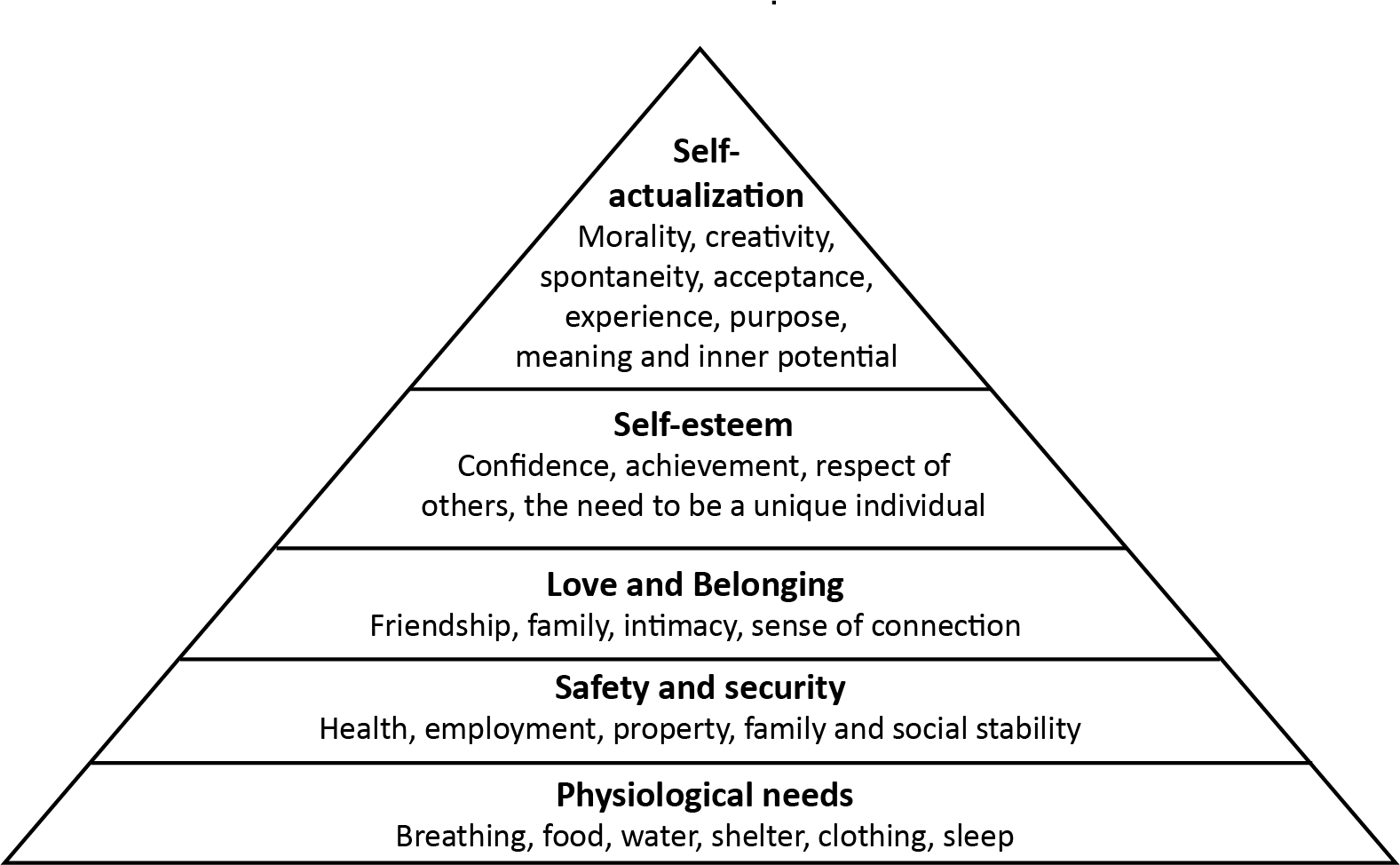

An enormous amount of research has been devoted to the numerous factors that impact a person’s motivation. Maslow (1943) argued in his theory, coined the Hierarchy of Needs, that individuals seek to fulfill basic needs as they ultimately strive to reach a level of self-actualization, living to their full potential.

Figure 4-2. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Maslow suggested that a person would not be able to deal with certain higher level esteem needs, such as a need to have a sense of achievement like earning a college degree, without having met basic physiological or safety needs, like having proper food and financial security. Dembo and Seli’s (2008) survey of factors that impact the motivation of college students focused upon three main factors: sociocultural context, classroom environment, and internal beliefs and perceptions. To summarize, the value that your culture or parents place on the importance of a college education may provide a sociocultural context that places education as a high priority or not. Also, the classroom environment can impact motivation based on the size of class, the time of day it is offered, the compatibility of the teaching style with your learning style, and level of instructor guidance and support. Finally, your internal thoughts and feelings greatly impact your level of motivation. For instance, students who are more mastery goal-oriented (i.e., learning for the purpose of self-improvement) tend to exhibit a more positive attitude and long-term retention of information in comparison to students who are more performance goal-oriented (i.e., completing a task only to get the grade or to do better than someone else). Also, students who feel that they are capable of completing a task are more likely to engage in that activity, more likely to receive positive feedback from that activity, and therefore feel better about themselves in general. On the flip side, if students do not feel like they are capable of succeeding in a task, they will oftentimes avoid completing that task and experience the negative consequences; however, the safety mechanism is that they really did not try so their self-worth remains relatively intact.

It is also believed that certain types of motivation are associated with more positive outcomes in an academic setting. Using a series of psychological assessments, Vallerand and Bissonette (1992) identified students as either intrinsically motivated (i.e., engaged in behaviors for the pleasure or satisfaction of performing in those behaviors), extrinsically motivated (i.e., engaged in behaviors due to an external reward, avoidance of negative consequences, or as a means to an end) or amotivational (i.e., perceived lack of control or purpose). They found that students who were more intrinsically motivated were more likely to be enrolled one year later. In addition, they found that students who were identified as having self-determined forms of extrinsic motivation were also more likely to be enrolled in college one year later. However, students who were identified as amotivational were unlikely to be enrolled in college one year later. Students for the most part report that they are motivated to earn a college degree, but then ultimately, faculty and staff on college campuses often report that students do not complete the work necessary to earn that degree. Why the disconnection? The question on the minds of many students is, “studying is not always fun, so how can I get motivated to study?” Overall, research presented above indicates that students who gain a level of satisfaction from the learning process or have determined for themselves that it is important to earn a college degree are more likely to get the job done. Refer to “How Can I Get Motivated to Study?” for some concrete ideas to boost your motivation.

How Can I Get Motivated to Study?

- Set goals! Set long-term, short-term, and weekly goals. Goals motivate students by focusing their direction and attention on a task (Dembo & Seli, 2008). Making your long-terms goals visual and salient help to keep them in the forefront of your mind.

- Set a study session goal of what you plan to produce or know at the end of the session.

- Check a task off of a To-Do list and take the time to recognize the satisfaction that you have gained from completing a task that serves your goals. Along similar lines, think about how good it would feel to master a new or difficult topic.

- Reflect on the value of what you are learning. How might this help you in the real world? How might this new information or skill help you become more effective in a given situation?

- Make the information you are studying more interesting by looking at the pictures and reading the captions, Googling the topic on the Internet, thinking about how information personally ties to you, or asking yourself thought provoking questions like “What if ‘X’ happened? How would things be different?”

- Study a topic for a shorter segment of time and alternate with other subjects. For instance, read for history class for 30 minutes, then work on math homework problems for 30 minutes then go back and read for history again.

- Make studying more “social”—form a regular study group or talk with your faculty member. Learn more about study groups in Chapter 5: “Collaborative Student Learning: The Art of Study Groups.”

- Schedule routine study times for topics.

- Reflect on what will be gained by studying and how much self-control you feel by foregoing other lower priority activities.

- Consider the consequences of not studying now. How will you do on your next exam? How late will you have to stay up to get this work done, and how will you feel the next day? Will you have to give up another activity later that you would rather do?

- Make your study goals public to others and ask them for their support in helping you stick to your plan.

- Reward yourself. For instance, commit to not checking your e-mail or Facebook until you have completed your study session, or if you finish reading for your government class, you can watch your favorite TV show.

- Vary the study techniques that you use.

- Be more active in your study sessions like taking notes or developing notecards while you are reading.

- Reduce temptations! Turn off your cell phone, TV, Internet, and go someplace where there are fewer distractions.

- Select a major and classes within that major that you personally enjoy.

- Seek help when life is too stressful. It is hard to be motivated when you are feeling overwhelmed.

- Check your attitude. Are you approaching a situation as creator or a victim?

Adapted primarily from Muskingum College Learning Strategies Database (n.d.) and University of Victoria Learning Skills (2004).

Thought Question

- What motivates you to study? What techniques are you willing to try the next time you are not feeling motivated to study?

- Why did you come to college?