8.2 Career and Major Exploration as a Process

Let’s start this section with a brief activity about your thoughts on major and career exploration.

Activity 8-3:

Determine if the following statements are true or false.

| Most students select a major based on solid research and information gathering about the field. | TRUE | FALSE |

| Once students declare a major, they will stick with it. | TRUE | FALSE |

| Students should choose a major based on the current job market. | TRUE | FALSE |

| Students should choose a major directly related to their chosen career. | TRUE | FALSE |

| Once students commit to a major, they will be stuck in that career for life. | TRUE | FALSE |

| A student with a liberal arts degree will not be qualified to get a really good job. | TRUE | FALSE |

| Students only need a high GPA to improve their chances of career success. | TRUE | FALSE |

In the past, young adults simply followed in their parents’ footsteps taking over the family business or farm. However, in the beginning of the 20th century, Frank Parsons in Boston began to assist disadvantaged youth in choosing careers. His emphasis on matching self and job traits has remained at the core of the development of career decision-making programs (Baker, 2009). Today, students are entering a workplace unlike the generations before them, given the impacts of globalization, downsizing, re-engineering, and changing organizational structure of the workplace (Gordon, 2006). Students need to make a conscious effort to prepare themselves for this changing world to be competitive and ultimately find their own happiness.

When you were a young child, it was fun to think about being an astronaut, a veterinarian, or a firefighter. Many people also imagined being in a cool career that was portrayed on television—a forensic scientist from CSI, an emergency doctor like in ER, or lawyer from Law and Order. However, as you come closer to entering the workforce, you may be feeling more anxiety about your career, major choice, or have absolutely no idea what you want to do with your life… and that is perfectly natural. According to Beggs, Bantham, and Taylor (2008), statistics vary, but up to 50% of students enter college undecided. Those students, who have selected a major, ranked “information search” last in importance in selecting a major, indicating that decisions may have been made without critical information about themselves and the field. Allen and Robbins (2008) reported that 75% of students change their major at least once in college.

If you think back to the academic journey discussed in Chapter 2, you may recall that there are many different pathways to get from Point A to Point B. Likewise, your career path will merely be a continuation of your academic journey, and it may take you in different directions at different points in your life, possibly even bringing you back to school or to another type of formal training when new jobs are created. Whether you have a major identified or not, engaging in major and career exploration in your first year in college could help direct you toward a more satisfying academic and career path more quickly and save a lot of heartache in the long run.

Career exploration during college is also important because you will change and grow tremendously during this time according to your experiences and studies. Beyond studying one subject, you will make new friends, explore new ideas, find mentors, and have chances to study abroad and complete internships. All of these experiences will inform your choice of a major and career.

Relationship between Majors and Careers

Today, the college degree is the entrance ticket to the workplace. Students need to understand the importance of completing their degree while learning as much as they can along the way. A student’s persistence in completing a degree is an indicator of many of the qualities that employers are looking for in a new hire: strong work ethic, motivation and initiative, problem solving, etc.

Some professions require certain degrees, such as nursing and engineering, which require professional examinations for licensure. However, your college major does not necessarily define your career path. For instance, students do not necessarily have to major in the sciences in order to apply to medical school as long as the proper prerequisites and MCAT test scores have been attained for admission. Liberal arts majors develop many of the skills that employers are seeking in new hires, so it is plausible for those students to enter a wide variety of fields, such as business and helping professions. Not only attending to learning the material in courses, but also reflecting on the development of transferable skills is crucial. It is ultimately more important to study subjects you are interested in and successfully graduate than to focus on a major that you think you have to have for a particular career path.

Top Ten Qualities/Skills that Employers Seek

According to the National Association of Colleges and Employers Job Outlook 2010 Report, employers are looking for the following skills and qualities in their new hires:

- Communication Skills—written and verbal

- Strong Work Ethic

- Motivation and Initiative

- Interpersonal Skills—relating well to others

- Problem-Solving Skills

- Teamwork Skills

- Analytical Skills

- Flexibility and Adaptability

- Computer Skills

- Detail Orientation

The Career Exploration Process

According to Gordon (2006), “choosing and maintaining a career is a life-long process” (p. 15). Just as students change their majors in college when they realize the fit may not be optimal, people change their careers or directions within the same career. Donald Super proposed that career development activities were related to an individual’s self concept (Career Services, 2010). According to Super, self concept changes throughout life based on a person’s experiences. Not surprisingly, students of traditional high school and college ages fall into the Exploration stage (refer to Table 8-2).

| Stage | Age Range | Characteristics of the Stage |

| Growth | Birth-14 | Development of self concept, attitudes, needs, and general world of work |

| Exploration | 15–24 | “Trying out” through classes, work experience, and hobbies. Tentative choice and skill development occurring |

| Establishment | 25–44 | Entry-level skill building and stabilization through work experience |

| Maintenance | 45–64 | Continual adjustment process to improve position |

| Decline | 65+ | Reduce output and prepare for retirement |

Developing career exploration skills can be beneficial throughout life.

Thought Question

How might a person continue to use career development skills during the Establishment and maintenance stages?

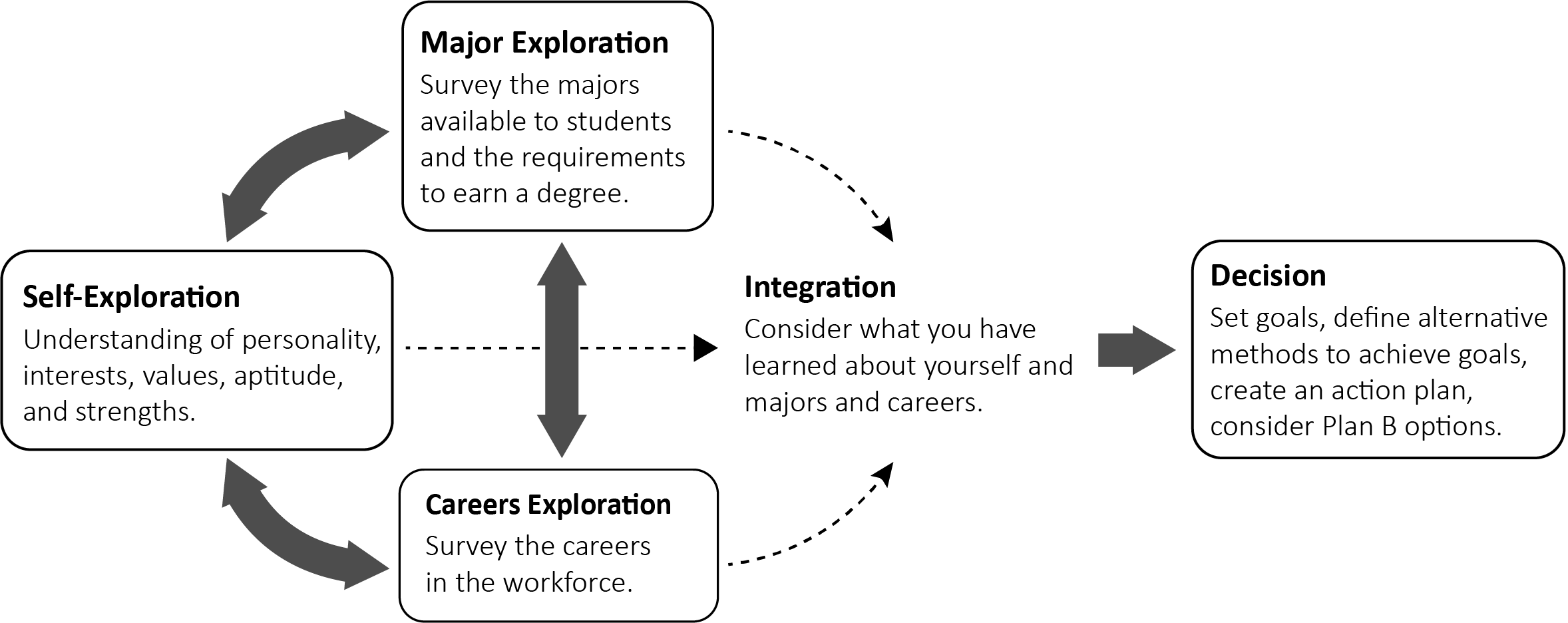

In general, students need to engage in a process of collecting information—though what information they need to collect would depend on what questions a student may have (refer to Figure 8-1).

Adapted from Gordon’s 3-I Process (2006).

Even if you think you know what your major and career path may be, it helps to gain more information about the selected major to ensure your strengths and abilities match with the major and determine if that major will help develop skills needed for a career. It is also helpful to know more about how your values and personality might align with a particular major and career path.

Careful research can be done using a variety of resources including services on campus, Web resources, and experiential learning opportunities (see Table 8-3).

| Self-Exploration | Major Exploration | Career Exploration |

| UT Arlington Counseling and Psychological Services CAPS Workshops and Events Myers-Briggs Type Indicator Group Interpretation Seminar |

UT Arlington Undergraduate Catalog UTA Course Catalog Listing of majors offered at UTA |

Occupational Handbook Bureau of Labor Statistics |

| Lockheed Martin Career Development Center LMCD Self-Guided Resources Focus 2 online tool to help identify interests, values, and skills |

Experiential Major Maps (EMMs) Experiential Major Maps Guide |

Lockheed Martin Career Development Center UTA Career Development Center |

| Kiersey Temperament Sorter® kiersey.com Available for free online |

UT Arlington Academic Departments UTA Schools and Colleges Listing of academic departments on campus |

Volunteer Join UTA Volunteers; Take a class that offers a Service Learning Component Center for Service Learning |

| Grades in introductory major-based courses | Informational Interviews Talk with professors in the department of interest or advanced students from that major. Refer to “How to Conduct an Informational Interview.” |

Informational Interviews Talk with professionals in a field of interest. Refer to “How to Conduct an Informational Interview.” |

| Reflection on hobbies that you enjoyed and subjects you performed well in high school | Enroll in an introductory major-based course | Internships Handshake, UT Arlington’s job and internship search site LMCD Handshake Resources |

Who Can Help You Integrate the Information Collected in Your Research?

- Academic Advisor from Division of Student Success or a major department

- Counselor from Counseling and Psychological Services

- Career Counselor from the Lockheed Martin Career Development Center

How to Conduct an Informational Interview

Informational interviews can be tremendously useful for various reasons. An informational interview can help you decide on a career path, verify that you are on the correct career path, or help you possibly identify professionals that could be of assistance in finding a job or internship in the future. Also, talking with someone in a position that you would like to have someday can inform you on what experiences and courses may increase your probability of success in a particular career path.

- One of the most difficult aspects of conducting an informational interview, beyond finding the courage to talk with a complete stranger, is to find the appropriate people to interview. Ask people you know to see if they might have a “connection.” You can also contact staff members at UT Arlington’s Alumni Association or the Career Center.

- Once you find someone and schedule a meeting to last approximately 15–30 minutes, research the organization that employs them. It might give you ideas on questions that you might ask.

- Develop a list of questions for your interview. Consider these sample questions:

- What is the title of the interviewee’s current position in the company?

- How did the interviewee get to his/her current position?

- What type of job tasks does the interviewee perform in this job?

- What does he/she enjoy/dislike about the current job?

- Does he/she know of similar careers that also use these job skills?

- What is the interviewee’s work history and how does he/she think that has impacted his/her current position?

- What is the interviewee’s educational background?

- What are the top five skills that the interviewee believes have been important to his/ her job life?

- What five things does the interviewee believe have been most important in his/her overall life?

- What advice would the interviewee give you?

- On the day of the interview, dress well and arrive early. A good first impression sets the stage for a good interview… and you never know if this person might someday have an opportunity for you.

- During the interview, record the answers to your prepared questions.

- Once you have completed the interview, send a thank you note to your host in appreciation for his/her time and expertise.

Once the exploration process has been completed, the information collected needs to be compiled for integration and interpretation of the options available to a student. The decisions and next steps that a student would take depends on what he/she may be ready to take on at that moment. In some cases if a student is completely undecided upon entering college, finding a major is a good first step and career exploration can continue to occur. If a student has decided on a major, information may confirm that staying with that major is a good decision or that changing to another major may be warranted given that interests and strengths do not align well. It could be that it was discovered that the career of primary interest is highly competitive and preparation for a “Plan B” needs to be considered. Circumstances change constantly so considering the information presented at each juncture is very important.

Once a particular decision has been made, the next steps include developing a set of goals and action steps that will help you achieve those goals. Revisiting the goal-setting process discussed in Chapter 4 can help you manage that process and adjust as circumstances change.

In conclusion, remember that you are right where you need to be according to Donald Super’s Life and Career Developmental Stages (Career Services, 2010). This is the time for major and career exploration. (Refer to Career Planning Timeline for more information.) What better place to explore than a great university? Take advantage of the resources that we have highlighted in this section and all that is offered on this campus. Remember that if what you choose fits your skills, interests, personality, and passions, it is probably a good fit. Remember also that you are not stuck with that major or career for the rest of your life; career development is a lifelong project.