20 The people without faces and the fight against the unjust by Andrea Macias

An example student research essay

*** Students, please remember, that any unacademic use of this essay (i.e. plagiarism) submitted in class will result in failing the course.

(Cover page start)

The people without faces and their fight against the unjust.

Andrea Macias Estrada

College of Liberal Arts, the University of Texas at Arlington

Art 1317: Art of Africa, Asia, Oceania, and The Indigenous Americas

This essay follows Prompt 1 and is in APA style citation. I am not a Native English speaker but I am comfortable speaking or writing in English. This is my first research paper.

(Cover page end)

(Essay start)

The people without faces and their fight against the unjust.

Liberty is one of the greatest things a person could ever have. Education, jobs, and democracy are all things that would not be accessible without it. It is also the thing that many people still seek and continue to fight for. Throughout history, we’ve seen what happens when communities are stripped away from such power and are left defenseless, a shadow amongst the rich and powerful with nothing to depend on but each other and whatever resources they are left with. Unfortunately, many of these communities, people, and parts of history have faded away over time because of this cruelty. But many are still here, continuing to live and fight for a better future and treatment no matter the restrictions and threats that those in power may hold against them. In this case, we will explore Isaac Guzman’s “Dia de Los Fieles Difuntos.” (Figure 1) piece as an example of the power that communities and social movements hold as well as why it is so important for us to question and stand up against the unjust treatment of undermined communities.

“Dia de Los Fieles Difuntos.” (Figure 1) translates to the well-known Mexican holiday, Day of the Dead, where families and friends commemorate their lost loved ones in a day full of all sorts of festivities. In Isaac Guzman’s photograph (Figure 1) we see the E.Z.L.N community, also known as the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, hold a candle-lit ceremony in remembrance of the people lost in the battles of January 1994 in San Cristobal De las Casa, Chiapas, Mexico. (Guzman, n.d.) The picture is captured in black in white as Guzman captured the moment with a film camera and with nothing else to illuminate the scene but the candles that people hold, perhaps intensifying the feeling of grief that comes along with learning the story behind the photograph (ibid). The people here are seen looking into the camera, their sadness, and tired eyes obvious to the viewer as they are the only thing that can be seen through their masks. The image leaves the viewers with many unanswered questions but mainly as to who these people are and what their story is.

The E.Z.L.N is a political group in Chiapas, Mexico, mostly composed of the Tzeltal, Tzozil, Chol, Tjolobal, Zoque, Kanjobal, and Mame indigenous communities (Reyes Godelmann, 2014). The group was founded in 1983 as a union against the Mexican Government for its mistreatment of the indigenous communities, unfair land distributions, and lack of democracy for its native population (Britannica, 2017). On January 1st of 1994, the group marched into the city of San Cristobal and made itself public, declaring war on the Mexican Government and taking over San Cristobal along with three other towns on the same day. After a series of violent days, EZLN and the Mexican Government came to an agreement and settled the battle. Despite their victory, it was not until years later that a portion of their agreements were met (Ibid). Meanwhile, the Mexican Government had spent its time funding paramilitary groups to take the EZLN down and take back the land. (Ibid). As of 2001, the Mexican Government granted its indigenous populations freedom of autonomy (Reyers Godelmann, 2017), and as of today the Zapatistas control the majority of Chiapas and have put in place their own laws and government to protect their community (Britannica, 2017) (Klein, 2019). Although they still deal with the trauma and loss that came during and after the rebellion they continue their fight. Opening up a world of new opportunities for their members and inspiring many others to join the cause (ibid).

Connections Throughout History

Guzman’s E.Z.L.N piece can be related to that of Ren Renfa’s “A Fat and Thin Horse.” After the Yuan Dynasty came into place in China it was not taken well by the people who still supported the old Government, but alas they could not speak freely about it as any contradictions to the Yuan Dynasty could have endangered them (McCurdy, 2022b). However, a group of scholars now called the Song Loyalists still found ways to support what they believed in and used art as a format of political expression (ibid). Similarly, the Zapatistas faced many dangers from the Government when it came to being a part of the liberation movement. On December 22 of 1997, 45 men, women, and children were massacred in their own homes in Acteal, Mexico for suspicion of conspiring with the E.Z.L.N (Changiz, 2020). This was a clear indication of the many dangers that came with being a member or supporter of the EZLN. But also of how necessary it was for a stand to be made against the oppression and abuse of the native people of Mexico. Nevertheless, the Zapatistas continued their fight and supporters like Issac Guzman have followed them in the process, capturing moments in photographs to help spread awareness about their cause and history (Guzman, n.d).

The “Plank Painting” of Clack Island, Australia is another great piece with a similar concept to that of the E.Z.L.N. The Aboriginal people in the islands of Australia often used bark as canvases and painted many of their sacred stories and ancestors onto these pieces of wood (McCurdy, 2022c). These paintings were often held on Clack Island because of its spiritual importance to the Yidhu Warra people, similar to the painting themselves, the land was used to honor their passed loved ones and ancestors (Ibid). Like many other non-western art pieces, these paintings were stolen by an exploration group and eventually sold off to a Museum with complete disregard to the importance of these items and where they came from (ibid). In the case of the Zapatistas, The Mexican Government planned to privatize their communal farms as part of the North American Free Trade Agreement, also known as NAFTA (Britannica, 2017). Of course, the government did not consider how privatizing these lands would affect its indigenous communities and completely disregarded them when it came to making this decision. Because of its rich natural resources, a large majority of Chiapas’s indigenous population works in agriculture as it is one of the few ways the people can provide for themselves and their families (Reyes Godelmann, 2014). Without their communal farms, many of these people would be left without any form of income leaving them to starve, and worsening the percentage of poverty amongst the native people (ibid). Thus EZLN made itself public on January 1st, 1994. The same day that NAFTA went into effect (Britannica, 2017).

Similar to the way the Indigenous people of Chiapas were ignored from their own lands and of their ownership over them “Monk’s mound.” and “Serpent mound.” are other cases in which Natives were disregarded and denied of what was rightfully theirs (McCurdy, 2022c) Monk’s Mound is one of the many mounds that was built by Native Americans along the Mississippi River ( late 1600s CE) (ibid). Some of these mounds were created to support structures, while other mounds such as Serpent Mound have more spiritual meanings and were meant to represent animals that were sacred to the Native Americans (ibid). Despite the obvious involvement of the Natives, Euro – Americans denied the idea and instead fabricated mythologies about creatures that could have built the mounds instead (ibid). Refusing to credit the Natives for their hard work, creativity, and land. This denial of indigenous communities and what is rightfully theirs is not uncommon and has been seen throughout history time and time again, and it is exactly what the EZLN fights against and hopes to eradicate. In hopes of receiving better treatment and credit for themselves and for the many other indigenous communities in Mexico.

Ai Weiwei is an artist that released a collection of medical masks amid 2020, and although he left no indication or description of what the project was about, it clearly had to do with the ongoing epidemic (McCurdy, 2022b). At the time that Ai released his project, masks had become a part of the everyday life of many people across the world. Many felt unsafe without the masks and urged others to use them, while many others refused to do so and felt that it was not necessary and perhaps even a violation of their autonomy. The usage of masks became a conflicting topic and eventually a part of people’s identity and an indication of how they felt about the sickness. Similarly, the EZLN wear masks as a part of their identity (Schools for Chiapas, 2014b). Like other rebel groups, the EZLN have a trademark of their own and are commonly recognized by the black ski masks or red bandanas that they wear over their faces. The masks are a message, an indication of who they stand with and what they believe in. They are, of course, also used for protection as they keep their identities safe from those against them (ibid). Nonetheless, masks are clear to be more than just a fabric but also a part of who we define ourselves to be.

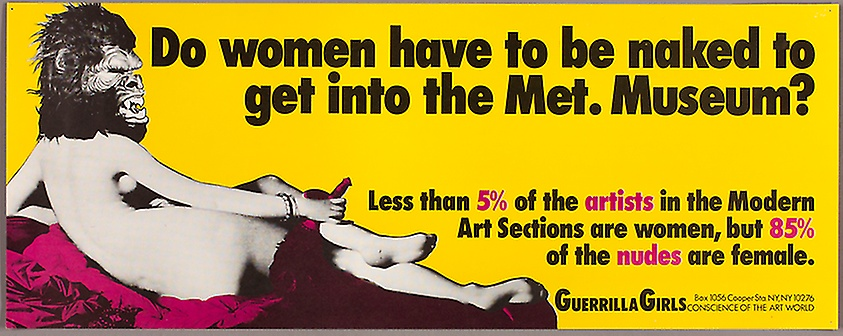

Women were and continue to be a major part of the EZLN movement. The Zapatistas not only challenge the government and colonialism but the patriarchy as well. Within the group, women have the ability to take on the roles of leaders, healers, teachers, and have a voice in community affairs (Kelin, 2019). They even made up to a third of the movement’s soldiers when it first began (Ibid). And it was a year before the EZLN made itself public that they had passed The Women’s Revolutionary Law (Marcos, 2014). Their first guerilla movement that granted women within the Zapatista movement the right to education, healthcare, income, and positions of leadership as well as the freedom to choose who they marry and how many children they want. As well as have any rape or violence made against them to be severely punished (Schools for Chiapas, 2014). Similarly to the Zapatista movement, The Guerrilla Girls challenged the patriarchy in their own way. Using guerilla tactics, just as the Zapatistas did, to promote their art and movement (McCurdy, 2022b). The Guerrilla Girls movement brought to light the discrimination against female artists and artists of color that took place in many well-known museums (ibid). Over time the Guerrilla Girls broadened their movement to many more social injustices and today continue to challenge the patriarchal ways and open new doors for women in their communities, just as the women in E.Z.L.N do.

The abuse and ill-treatment of undermined communities have been seen throughout all of history, and although much of it has changed a lot of this abuse still carries on in the modern day. That is why groups such as the EZLN and Guerrilla Girls (Figures 1 & 7) are so important, and why the history of those such as the Native Americans and Yidhu Warra people cannot be forgotten (Figures 3 & 4). It is the bravery of those who are willing enough to take a stand against the unjust that creates a pathway toward a better future. The impact that the EZLN has left on the Mexican and Indigenous communities is one that will last for many generations to come, and one that will inspire many others to take a stand as well. That is why it is so important to have their stories be known, and why it is so important to challenge the unjust, as even the weakest of voices can always become a part of something much bigger.

References

Britannica. (2017, June 23). Zapatista National Liberation Army. In Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Zapatista-National-Liberation-Army#ref286750

Changiz, M. (2020, December 22) 23 Years of Impunity for Perpetrators of Acteal Massacre. Nacla. https://nacla.org/news/2020/12/21/23-years-impunity-acteal-massacre

Guzman, I. Embers Burning in the Dry Grass. (n.d). Batsi lab. Retrieved 2022, from https://www.batsilab.org/embers-burning-in-the-dry-grass

Marcos, S. (2014, July 22). The Zapatistas Women’s Revolutionary Law as it is lived today. Open Democracy. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/zapatista-womens-revolutionary-law-as-it-is-lived-today/

McCurdy, L. Tsao, V. Garza, M. Martinez-Blas, E. Esswein, M. Lewis, M. Khazem, J. Frizzell, A. Dang, V. Cabella, S. Jammal, L. & Coleman, F. (2022). Where does Art Come From? (1st ed.) [E-Book] Mavs Open Press. https://uta.pressbooks.pub/wheredoesartcomefrom/

McCurdy, L. (2022b). Why do I have to do what you say? [E-Book]. In Where Does Art Come From? (1st ed.) Arlington, TX. Mavs Open Press. https://uta.pressbooks.pub/wheredoesartcomefrom/chapter/why-do-i-have-to-do-what-you-say/

McCurdy, L. (2022c). Why Do People Take What Doesn’t Belong To Them? [E-Book]. In Where Does Art Come From? (1st ed.) Arlington, TX. Mavs Open Press. https://uta.pressbooks.pub/wheredoesartcomefrom/chapter/why-do-people-take-what-doesnt-belong-to-them/

Klein, H. (2019, January 19). A Spark of Hope: The Ongoing Lessons of the Zapatista Revolution 25 Years On. Nacla. https://nacla.org/news/2019/01/18/spark-hope-ongoing-lessons-zapatista-revolution-25-years

Reyes Godelman, I. (2014, Jul 30). The Zapatista Movement: The Fight for Indigenous Rights in Mexico. Australian Institute of International Affairs. https://www.internationalaffairs.org.au/news-item/the-zapatista-movement-the-fight-for-indigenous-rights-in-mexico/

Schools for Chiapas.(2014). Zapatista Women’s Revolutionary Laws. https://schoolsforchiapas.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Zapatista-Womens-Revolutionary-Laws.pdf

Schools for Chiapas.(2014b). An Examination of the history and use of masks and why the Zapatistas cover their faces.http://schoolsforchiapas.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Whats-behind-the-mask_.pdf