19 The Post-Colonial Igbo Identity by Chinamerem Ahuchaogu

An example student research essay

*** Students, please remember, that any unacademic use of this essay (i.e. plagiarism) submitted in class will result in failing the course.

(Cover page start)

The Post-Colonial Igbo Identity

Chinamerem Ahuchaogu

Department of Art & Art History, University of Texas Arlington

ART 1317: Art of Africa, Asia, Oceania, and the Indigenous Americas

This essay is following Prompt 2, and is in APA format with Chicago style citation frequency. I am a native English speaker and have written a couple of research papers.

(Cover page end)

(Essay start)

The Post-Colonial Igbo Identity

What does it mean to be “African”? This would be a difficult enough question to answer, but it is complicated even further by the lasting effects of Europe’s colonial era. Colonization violently disrupts the core identity of a culture and the people within it. To explore how colonization affects an individual’s perception of the world, I interviewed my 73-year-old grandmother, Celine Nwatụrụọcha of the Igbo tribe of Nigeria.

Mrs. Nwatụrụọcha has a very different identity than me, as I am a younger agnostic male who was raised by Igbo parents in the United States, and she is an older Christian woman raised completely within Igboland and Igbo culture. She has spent most of her life in her village in Imo State, Nigeria. When she was born, Nigeria was still completely controlled by the United Kingdom. Nigeria’s “independence” came when she was 6 years old. While on a video call, for each artwork, I sent her the image and asked her for her opinion on it without any context. I then explained the context of the artwork and asked for her opinion on the art and the culture surrounding it. The call took about an hour.

The first artwork we looked at was Scramble for Africa (Figure 1) by Yinka Shonibare MBE (McCurdy et al, 2022b). The artwork depicts headless figures adorned in “tribal” clothing, around a table with a map of Africa on it (ibid). As the name informs, this represents the Scramble for Africa, or the period of European imperial expansion throughout the African continent (ibid).

Mrs. Nwatụrụọcha’s first impression of Scramble for Africa was that it looked very nice. She recognized and liked the fabrics that the figures were wearing, and talked about how the price of those fabrics are very expensive now. When I gave the context that the piece represents the colonization of Africa from a critical point of view, she said that she still liked the piece, as long as there are no “devilish” connotations. When asked to elaborate, she explained that the effects of British colonization on Igboland are not so bad to her, because they are also the ones that brought us Christianity. She feels that non-Christians can do whatever they want, as long as they let Christianity be practiced.

I then explained to Mrs. Nwatụrụọcha the meaning behind the fabrics the figures are wearing. They are originally wax knockoffs of batiks, a cloth indigenous to Indonesia (McCurdy et al, 2022b). These knockoffs were created by the Dutch East India Company when the Dutch were in control of Indonesia (ibid). However, they were not popular among the indigenous people of Indonesia, so the Dutch sent them to West Africa (ibid). Now they are part of how the outside world views Africa, and even how many Africans view themselves (ibid). Mrs. Nwatụrụọcha responded that she did not know the fabrics weren’t indigenous to West Africa, and this interested her. However, she insisted that the fabrics are still nice.

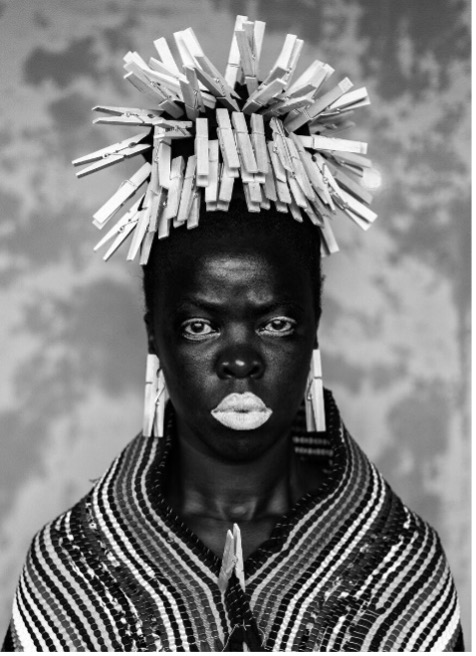

Clothing is an essential component of a culture’s identity, and while cultures evolve and take influence from other cultures, many core aspects of West African identity have confused and harmful origins. This is a major point in Zanele Muholi’s Bester I, Mayotte (Figure 2), focused instead on the specific history of South Africa (McCurdy et al, 2022b).

This piece is all about the Western perception of Africa and the people from there. Muholi depicts themself as a “savage” being adorned in an elaborate clothespin headdress and “tribal” cloth (McCurdy et al, 2022b). Through this piece, we can see that the elements implanted in African cultures for profit are often weaponized against them with harmful stereotypes. All of this confuses a cultural identity as we struggle to figure out what is “ours.”

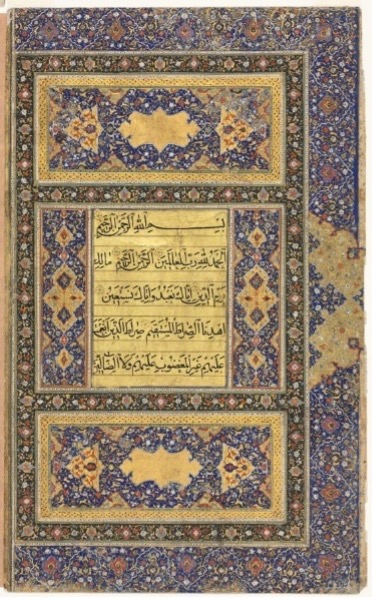

The next artwork I showed to Mrs. Nwatụrụọcha was the Qur’an Manuscript Folio (Figure 3) by the Safavid Period Maker(s) of Herat, Iran (modern-day Afghanistan) (McCurdy et al, 2022b). This is an incredibly decorated page from a 16th century Qur’an with dynamic colors and intricate calligraphy (ibid). It is clear from this page that aesthetic appeal is critical in this culture. How one writes in this culture is reflective of their soul (McCurdy et al, 2022a).

When I showed this to Mrs. Nwatụrụọcha, she recognized it as the Qur’an immediately. She commented that it’s mainly the “northerners” that are associated with it, and as a Christian, she’s not comfortable with it. The “northerners” she refers to are the Hausa-Fulani peoples that populate northern Nigeria. In the colonization of Nigeria, over 200 different tribes were grouped in with each other with no regard for their respective beliefs and cultures (Staunton, 1999, p. 514). In the mid-20th century, violent tensions rose across the board, especially between the majority-Christian Igbos and the majority-Muslim Hausa-Fulanis (ibid). These tensions led to the Biafran War and genocide, in which over one million people died (Gribbin, 1973, p. 49). Many of these people were Igbo, and many of them children (ibid). They were deliberately starved out by the Nigerian government, who were heavily aided by the British government (O’Sullivan, 2017, p. 17). This period caused many traditional Igbo practices to die out, as upkeeping them took a backseat to staying alive. Violent tensions from the war still exist today. Mrs. Nwatụrụọcha was in her late teens when war broke out, and is still apprehensive about Islam. Even without the religious context, she stated that she doesn’t like it aesthetically because she doesn’t know what it means. The violence caused by colonization not only stifles the practices in one’s own culture, it also can prevent people from appreciating aspects of different cultures, due to the scary connotations they may have.

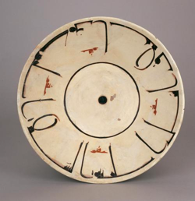

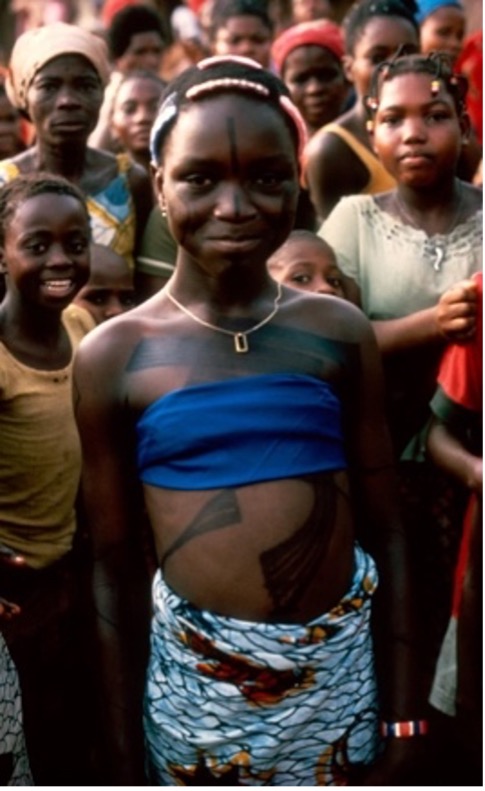

In Islam, writing is of the utmost importance because it has spiritual connotations. This importance can be seen in a variety of material outcomes including architecture, like in the changes made to Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, Turkey (Figure 4) and on an inscribed ceramic bowl (Figure 5) (McCurdy et al. 2022b). Likewise, writing was once critically important in Igbo culture as well, and still is in some areas. Uli is a traditional Igbo practice of body painting predominantly on women, by women (Willis, 1989, p. 62) (Figure 6). Special symbols are painted on a woman’s body that can represent love, beauty, and other concepts (ibid). It is often done for rites of passage in a woman’s life, like marriage, the birth of her first child, or when she obtains a title status (ibid). It is primarily a female practice because of its association with Ala, the female deity of the earth in the traditional Igbo belief system (ibid, p. 63).

When I asked Mrs. Nwatụrụọcha about this practice, she responded that it is something that is rarely done at her village – only by some people and on very special occasions. She said that she personally doesn’t like it, as she likes to be “simple,” and when asked why it is dying out, she replied that it is likely the result of Christianity. However, she doesn’t see this as a bad thing; in her view, Igbo people “respect the vow to God so much” that they are willing to let go of these things. The imposition of Christianity on Igbo culture has pushed out many traditional practices and beliefs, as they are often seen “demonic.” What many Igbos see as “Igbo culture” can be heavily skewed by European influences.

The next artwork I showed Mrs. Nwatụrụọcha was the Asa Kate Mask of the Astrolabe Bay people of Papua New Guinea (Figure 7). This mask represents the spirit Asa, who is an important figure in the life of a young Astrolabe Bay man of Papua New Guinea (McCurdy et al, 2022b). The Astrolabe Bay people have a tradition of circumcision, and this event is a key point in a boy’s transition to manhood (ibid). Boys must overcome their fear of Asa’s “bite” (circumcision) to become men (ibid).

Mrs. Nwatụrụọcha initially thought that it was from a Nigerian tribe. She said that people often keep things like this for spiritual reasons, to respect their forefathers, or even as decoration. However, she doesn’t like it because she feels that these deities should be left in the past now that we have Christianity. When I gave more context about the mask and the surrounding culture, it seemed to strengthen her aversion. She expressed concern for children that are raised in these traditional beliefs without access to Jesus, and feels that these other deities around the world and in Igbo culture are invalidated by Christianity.

The Asa Kate Mask is visually similar to the “mmanwu”, or masquerades, that are present throughout Africa, including Igboland. One such masquerade is Agbọghọ Mmụọ, or the maiden spirit (McCurdy et al, 2022b). These masks and the performances that accompany them represent the Igbo ideal of feminine beauty: spiritual, gentle, nurturing, and dynamic (ibid).

I showed Two Types of Agbọghọ Mmụọ Masks (Figure 8) to Mrs. Nwatụrụọcha, and she recognized similar masquerades from her village. According to her, people in similar masks perform these masquerades around celebratory periods, and some use the masks as decoration. To her, these performances and decorations are purely for entertainment and don’t have spiritual connotations anymore. Because of this, she is okay with them and even likes them to some degree.

After explaining to Mrs. Nwatụrụọcha how Agbọghọ Mmụọ is supposed to represent the ideal woman an Igbo culture, she seemed pleased. She stated that most of the masquerades in Igbo culture depict men and concepts surrounding men, so it is nice that there are also masquerades that depict women. This was a more positive response than I was expecting, and it illustrates the importance of gender representation within a culture. However, this resonance is only possible for Mrs. Nwatụrụọcha if the traditional, spiritual connotations are completely divorced from the art. This is the ultimatum for many traditions in colonized cultures; either they get left in the past, or they survive as shells of what they used to be.

The practice of colonization leaves long-lasting effects on the identity of a culture. The violence and confusion it causes can skew how a people view their culture, themselves, and the outside world. It is important that we all set out to rid ourselves of the stereotypes and negative connotations that we obtained from colonial practices – to see ourselves with our own lenses, and be cautious of the lenses we use to view others. We have a long way to go, but it is more than worth the effort.

References

Gribbin, R. E. (1973). Two Relief Crises: Biafra and Sudan. Africa Today, 20(3), 49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4185324

McCurdy, L. M. and class discussants (2022a). “What is Divine.” Lecture Series at the University of Texas at Arlington, February 2022.

McCurdy, Leah, Victor Tsao, Marizela Garza, Emery Martinez-Blas, Maria Esswein, Mya Lewis, Jessica Khazem, Allyson Frizzell, Emily Berkes, Lina Jammal (2022b) Where Does Art Come From? Arlington, TX: Mavs Open Press. https://uta.pressbooks.pub/wheredoesartcomefrom/

O’Sullivan, K. (2017). Back to BIAFRA. History Ireland, 25(3), 17. http://www.jstor.org/stable/90014528

Staunton, E. (1999). The Case of Biafra: Ireland and the Nigerian Civil War. Irish Historical Studies, 31(124), 514. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30007167

Willis, L. (1989). “Uli” Painting and the Igbo World View. African Arts, 23(1), 62–63. https://doi.org/10.2307/3336801