5 What Is Beautiful?

What is beautiful?

What do you think is beautiful? Many of us may respond, beauty is in the eye of the beholder, as the old saying goes. As we discussed in “Who Am I?”, ‘the eye of the beholder’ is another way of thinking about the ‘theory of mind.’ One beholder thinks differently than another beholder. When thoughts, values, and perspectives on the world are very common within cultural groups, we call them norms. Norms about beauty are the idealizations and expectations of how people should look in a society: what ‘good looks’ are. BTW, we’re focused on beauty norms for physical appearance but they also relate to aesthetic qualities of things, which we’ll come to later in the chapter.

Beauty norms or ideals for women often relate to facial and body features. Preferred characteristics become a shorthand for femininity. There are also cultural norms that reflect ideals for the appearance of men and masculinity. For example, if you went through an European or Euro-American educational system, it is very likely that you encountered imagery like Bust of a Youth by Francesco Mochi from 1630-1640 CE. Artworks like this are often used to illustrate primary school textbooks or public flyers because they exude many of the beauty norms of European and Euro-American societies. This marble sculpture represents a young man with lush curly hair, a symmetrical face, straight nose, plump cheeks, large open eyes, parted full lips, and strong chin in clean, polished white marble. With skill and precision, Mochi captured a portrait of a classically beautiful young man, according to long-established beauty ideals of the Western Canon.

But, Mochi and other artists of the Renaissance and Baroque periods misunderstood something about Greek scultpure… it wasn’t ever meant to be seen as bare white marble. It was lavishly painted with bright colors! Check out some examples reconstructed by scholars in “When the Parthenon had dazzling colours” (Haynes 2018). Following from what Renaissance artists thought were Greco-Roman traditions, European beauty ideals often coalesced around qualities such as light complexion, facial symmetry, and straight noses. White marble came to offer an aura of ‘whiteness’ and normalized the relationship of whiteness to purity in the Western Canon and ideals of beauty.

Such images and expected ways of representation reflect how people view others in their society. We all know that people look different and the vast majority of people in any culture do not ‘fit the mold’ of beauty ideals. Yet, we continue to set store by them. These ideals influence art and they become shorthand for not just good looks but ‘goodness’ in a society, as the discussion about the term “classical” in “Where Does Art Come From? An Introduction” demonstrates. What about global arts that do not fit the mold of classical beauty but focus on unique traditions developed without reference to ‘the classics’ of the Western Canon? This is one of the ways that art history has to reflect upon its biases. In this study of art, we are taking a global perspective and so must affirm the ‘theory of mind of cultures’ and be aware of the ways that beauty (as well as gender, sexuality, etc.) is relative.

Beauty is relative

For example, let’s take a trip to Tang Dynasty China (Fig. 5.1). Like in many periods of ancient China, people wanted to be buried in style. We’ll talk more about this in “What happens when we die?” Burials during the Tang Dynasty often included painted ceramic objects representing the types of things and people you wanted to populate your afterlife. Equestrienne (Fig. 5.2) (a French term applied to a Chinese artwork) represents a fancy lady on a fancy horse, indicating the companions that the deceased person buried with this object expected in the afterlife. We’ll be talking about the importance of horses in Chinese culture later. For now, let’s focus on this lovely lady.

She delicately leans forward upon the saddle, originally holding reins in her clasped hands. You’ve probably noticed her hair already. A voluminous up-do appears to be intentionally floppy and soft. Next, we focus on her face, a soft expression upon round cheeks and a plump chin. Her skin is pale, almost white. Then, viewing her flowing red robe, we notice delicate hands against a heavy-set frame, carrying weight in the belly and thighs. If you look closely, you also will notice her fashionable shoe inserted into the stirrup. Equestrienne probably sported red-rouged cheeks in its original state, emphasizing the weight of her face. Unfortunately, paint is often lost when objects are buried for long periods.

This lady is a large woman, not skinny as the European and Euro-American stereotypes of women of Asian descent assume, and she is presented with elegance and prestige. This representation reflects women’s beauty ideals during the early Tang Dynasty. In studies like “Chinese Palace-Style Poetry and the Depiction of a Palace Beauty” (Laing 1990), we find that Tang court ladies carried weight and weren’t shy about showing it off. Scholars suggest that these ideals can be attributed to a trend-setter known as Yang Guifei (meaning ‘Imperial Consort Yang’ but probably named Yang Yuhuan). Yang Guifei was the favorite consort of the aging Emperor Xuanzong. He was enraptured with her voluptuous figure, pale skin, and bold fashion choices.

One of Yang’s bold choice is understood through a story about an event at court. The story goes that Yang riding horses with other courtesans and attendants. By accident, she fell off the horse and the combs that kept her hair in a controlled bun also fell. With grace and pose, Yang regained her seat on the horse allowing her loosened bun and hair to flow around her face, framing her plumb cheeks and chin. This hairstyle received its own name: duomaji, literally “falling off the horse bun.” Through this storied experience and many others, including sacrificing herself for the Emperor, Yang Guifei set new standards for beauty and body type ideals.

The ‘whiteness’ of Yang’s skin was an important aspect of her beauty, but did not derive from assimilation of European norms (since there was only very distant knowledge of each other between China and Europe at this time). The ideal of pale skin tone for women in China developed independently, as a marker of their sheltered and elite lives. Elite women did not labor or toil, thus their skin was unaffected by the sun.

At around the same time Yang Guifei was shaking things up in Tang China, across the Pacific in what we now call the Americas, the cultures living around the Gulf Coast of Mexico (Fig. 5.1) also produced funerary objects representing women but focused on their own ideals of beauty. These cultures, like the Nopiloa and Totonac, lived in the Gulf Coast region well after the Olmec culture transitioned into other traditions. These cultures lived contemporaneously to the Classic Maya to the east.

Figure of a Woman in Ceremonial Dress (Fig. 5.3) is also made of ceramic but features a standing or seated woman wearing the finery befitting ritual events in her culture. She wears a huipil-like woven garment featuring a stepped-fret pattern (shapes with edges that resemble the geometric profile of a staircase), defined borders, and potentially hieroglyphic symbols on the sleeves. Imagine the color and texture of this intricate woven garment! She wears adornments such as a large beaded necklace, beaded bracelets, ear flares, and a headband with horn-like projections. The texture of her hair was carefully incised into the clay surface, accentuating a hairstyle commonly seen in this region: center-parted bangs. Her face is sensitively rendered with open eyes, parted lips making teeth visible, and full cheeks as if slightly tensed in a small smile. Scholars often note that figures from this region offer very expressive faces and charming demeanors, unlike typical depictions of sedate and/or neutral faces elsewhere. The artist employed selective naturalism, depicting her face with strong realism while abstracting her hands and lower body.

Given the adornments she wears, this woman obviously represents a position of prestige in her society. Her features communicate strength and power, complemented by the stability of her slightly forward-leaning form. Her identity is one of feminine status normalized in ancient Gulf Coast cultures. As a funerary object, this womanly representation would accompany the deceased in death, probably elevating the deceased’s position in the afterlife. Thus, this figure’s identity has an active purpose within this cultural worldview: to make the afterlife better. Like Equestrienne inspired by Yang Guifei, this proud woman of ancient Mexico demonstrates the significance of women’s identities in the past.

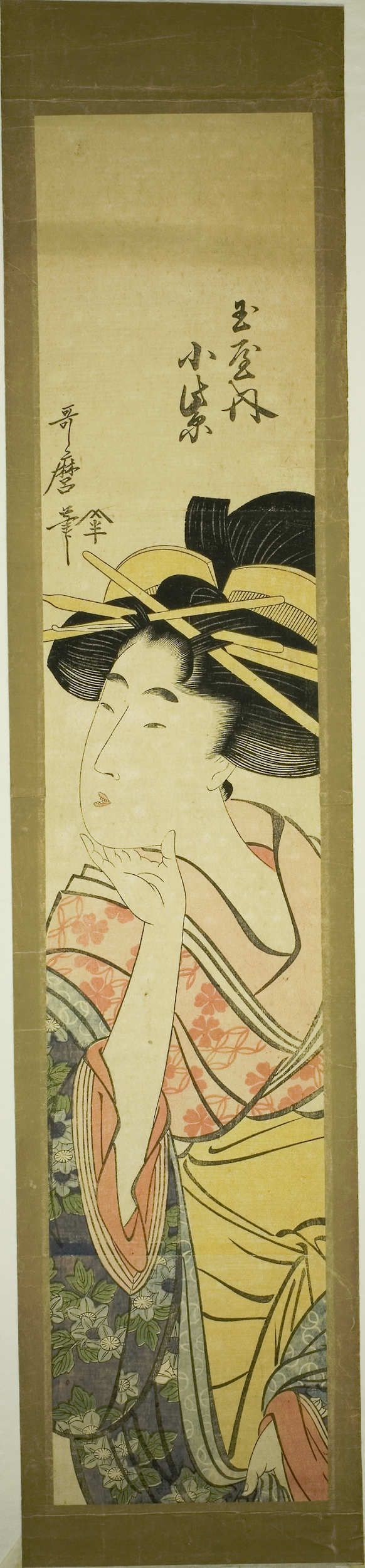

Over 1000 years later in Edo period Japan, artists created images of beautiful women, representing the unique ideals of Japanese society. The Courtesan Komurasaki of the Tamaya (Fig. 5.4) by Kitagawa Utamaro is a hashira-e, or ‘pillar print,’ produced using woodblock printing for very long and narrow proportions. To learn about the woodblock process, check out Japanese Woodblock Printing (Salter 2001). Such artworks would be perfect for hanging on a pillar in one’s home. The star of this hashira-e is a woman in an elaborate, multi-layered robe. She wears a complex hairstyle with ornamental pins and tortoiseshell combs, akin to the yoko hyōgo (“butterfly”) style. Komurasaki has a flawlessly pale complexion with diminutive facial features and a delicate hand cupping her chin. Utamaro’s composition accentuates the elongated profile of her face and neck. Differing stroke sizes used to render the facial features, hair, and the garments reflect the original painting choices and the skill of the woodblock carver to replicate that painterly variation in a different medium. These talents of the print designer and woodblock carver (not to mention the printer that ensured the many layers of color and pattern were executed well) combine to visually articulate the remarkable beauty of this woman.

We know the name of this woman from the calligraphy at the top of the print. On the right, we can read her name and title. (On the left, the artist/designer Utamaro signed his name.) Komurasaki was a famous yobidashi (“on call”) courtesan associated with the Tamaya brothel in the New Yoshiwara pleasure quarter of Edo (present-day Tokyo; Fig. 5.1). Visitors could only seek her services by making an appointment with the Tamayo teahouse, one of the most prestigious establishments where samurai, merchants, and intellectuals sought entertainment. Women like Komurasaki were considered the height of beauty in their day. The frequency of her depiction is testament to this. ![]()

Such celebrity portraits were part of the Edo culture’s ukiyo-e tradition. Literally meaning “pictures of the floating world,” ukiyo-e spanned landscape imagery, portraiture, narrative illustration, and erotica. In fact, many scholars trace the developments of contemporary manga and anime back to the surge of ukiyo-e in the Edo period. Check out Hokusai x Manga: Japanese Pop Culture since 1680 (Schulze et al. 2017) from more. In Edo, famous beauties, exuding the feminine presence and sexuality normalized for courtesans in Japanese society, offered the growing middle class an escape into ‘the floating world’ of social leisure. While some activities associated with pleasure quarters and ukiyo-e traditions were criminalized, many Edo people, including elites and royalty, refreshed themselves in their delights.

Superhuman beauty

Edo courtesans of Japan represented the epitome of the ‘earthly delights’ found in pleasure quarters of that time. Beauty also can emanate from non-earthly or superhuman sources, the divine and spiritual realms that impact many human societies. In southeastern Nigeria, Igbo peoples represent ‘the feminine’ in a performance centered on Agbogho-mmuo (literally “maiden spirit”), the divine and ultimate picture of womanhood. Figure 5.5 illustrates two examples of Agbogho-mmuo Masks. On the left, the larger mask is worn to conceal the dancer’s head entirely while the small mask (right) would primarily conceal the dancer’s face. The larger mask incorporates an exquisitely crafted coiffure (fancy hairstyle with adornments), accentuated by polychrome (multi-colored) paint. Both masks feature a similar face, with a prominent straight nose that connects the broad forehead to the large, slightly open mouth and accentuated chin. While her eyes are small in proportion, they are open and highlighted by the black curving diagonal lines that form an artistic “X” shape across her face. Her skin is white indicating her spiritual status, not an Igbo ideal of human skin tone. In the larger example, her supernatural complexion contrasts with black curls at her hairline and ascending curlicues then sweep the eye into her elaborate headdress of folding forms, and potentially some anthropomorphic elements. The patterned fabric at the base of the larger mask balances the detail of the coiffure and hides the dancer from view, enhancing the sense that divine Agbogho-mmuo is among mortals during a performance. The smaller mask was probably worn with similar fabrics to conceal the dancers. Dancers also wear a series of highly patterned garments to represent Agbogho-mmuo‘s specialness. Check out this historic photograph to see an example.

Agbogho-mmuo can represent femininity at all ages, though young women are most associated with this tradition (i.e. ‘maiden’ called out specifically in the spirit’s name). Nigerian-born Professor of English and Women’s Studies at Wichita State University, Dr. Chinyere G. Okafor enumerates the many qualities ascribed to the feminine identity in Igbo society: “communal, moral, good body shape and features, nurturing, gentle, vigorous, and dynamic” (Okafor 2007, 40). In public performances, Agbogho-mmuo entertains and instructs. The performance demonstrates what Igbo women should be from a divine authority, visualizing the sought-for identity of Igbo womanhood. Some Igbo groups prefer the Ijele masquerading tradition, focused on grandeur and excess (as in economic success) to reflect the scale of women’s roles in society. Ijele masks are known to tower over houses as they move through a village! Both Agbogho-mmuo and Ijele masquerades are spectacles celebrating Igbo women’s identity and beauty, from many angles. To consider many other examples of native African beauty ideals, check out the book The Language of Beauty in Africa Art (Petridis 2022) or visit the exhibition by the same name on view at the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, from April to July 2022.

In another way, artists of the Sukhothai Kingdom in ancient Thailand produced images of the most important divine figure within their cultural canon, Buddha, following guidelines about Buddha’s superhumanity. The Sukhothai people were devout Buddhists, taking up the religion after learning from Sri Lankan traveling monks. After about the 600s CE, Sri Lanka, unlike mainland India, sustained a large Buddhist population who were often on the move in Southeast Asia. As discussed in “What is Divine?”, the spread of Buddhism often inspired artists to incorporate pre-existing symbols to make images familiar to new groups. This also meant that pre-existing spiritual systems could merge with Buddhism, to form hybrid traditions. For example, new traditions developed that saw Buddha not just as a mortal man who reached enlightenment but as a divine figure like a god. We will explore one example of this in “What Happens When We Die?”

For now, we should consider how Sukhothai artists of Thailand (Fig. 5.1) chose to represent Buddha, according to their norms and historical conventions. Remember back to the traditional images of Buddha in “What is Divine?” Sukhothai artists produced sculptures like Walking Buddha (Fig. 5.6), distinct from that Indian imagery. Why are the Sukhothai examples unique? Firstly, Sukhothai rulers became very interested in the stories of Buddha walking around India teaching his message. The kings equated this practice with the way they ‘walked among their people’ seeing to the needs of the common man. This came in contrast to Sukhothai rivals, the Khmer rulers of present-day Cambodia, who the Sukhothai leaders considered to be very distant from their subjects. Thus, Sukhothai Buddhas are often portrayed walking versus sitting.

Perhaps more importantly, Sukhothai artists worked from the “signs of a great man” described in the Pali canon of Buddhist texts. Beyond the lakshanas listed in “What is Divine?”, Buddha had 32 primary and 80 secondary signs of greatness including “long, slender fingers,” “thighs like a royal stag,” soft, smooth skin,” “well-retracted male organ,” “ears … long like lotus petals,” and “arms … shaped like an elephant’s trunk.” These poetic reflections upon the Buddha’s image render his physical identity beautiful, complementing his spiritual beauty. To consider these ideals more, check out “Visualizing the Evolution of the Sukhothai Buddha” (Wisetchat 2013).

Can you recognize such traits in Walking Buddha? In bronze, Buddha’s skin is supple and smooth. The robe he wears clings to his form, enhancing this quality of softness. Do you notice the elephant trunk arm? His curving right limb follows the contour of his body and ends in long fingers almost reaching to his knee. His left hand, with slender fingers, is raised in the abhaya mudra, presenting a message to the viewer as if he is saying ‘don’t fear’ and ‘take reassurance from my presence.’ The curving quality of his arm is mirrored in the curvature of his very extended earlobes, a sign of the early life of material delights he left behind. Buddha’s thighs are accentuated with roundness. In addition, as Buddhist scripture codified, Buddha does not have a prominent penis or pelvic bulge. Sexuality and/or gender are not really relevant to the Buddha. While we use the pronoun “he” to describe Buddha, he transcended gender and sexuality through his enlightenment. Sukhothai artists accentuated this transcendent quality of Buddha by developing figures that appear androgynous (sex and/or gender is indeterminate; often intentionally when seen in art). In the Thai Buddhist tradition, Buddha is divine and thus not beholden to the norms of gendered identities of mere mortals.

Beauty ignored

Over time, many critical thinkers have questioned whether beauty norms and ideals are ‘a good thing.’ For example, we can ask whether Barbie’ dolls offer young girls realistic expectations for their appearance? Furthermore, many artists associated with Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transsexual, Queer, Intersex (LGBTQI+) communities question why beauty ideals and norms about appearance exist. How do such norms affect us as we mature? Do we have to conform to them? What happens if we don’t conform? One contemporary artist wrestling with these very questions is South African photographer Zanele Muholi (an individual who does not use gendered pronouns such as he or she) (Fig. 5.1).

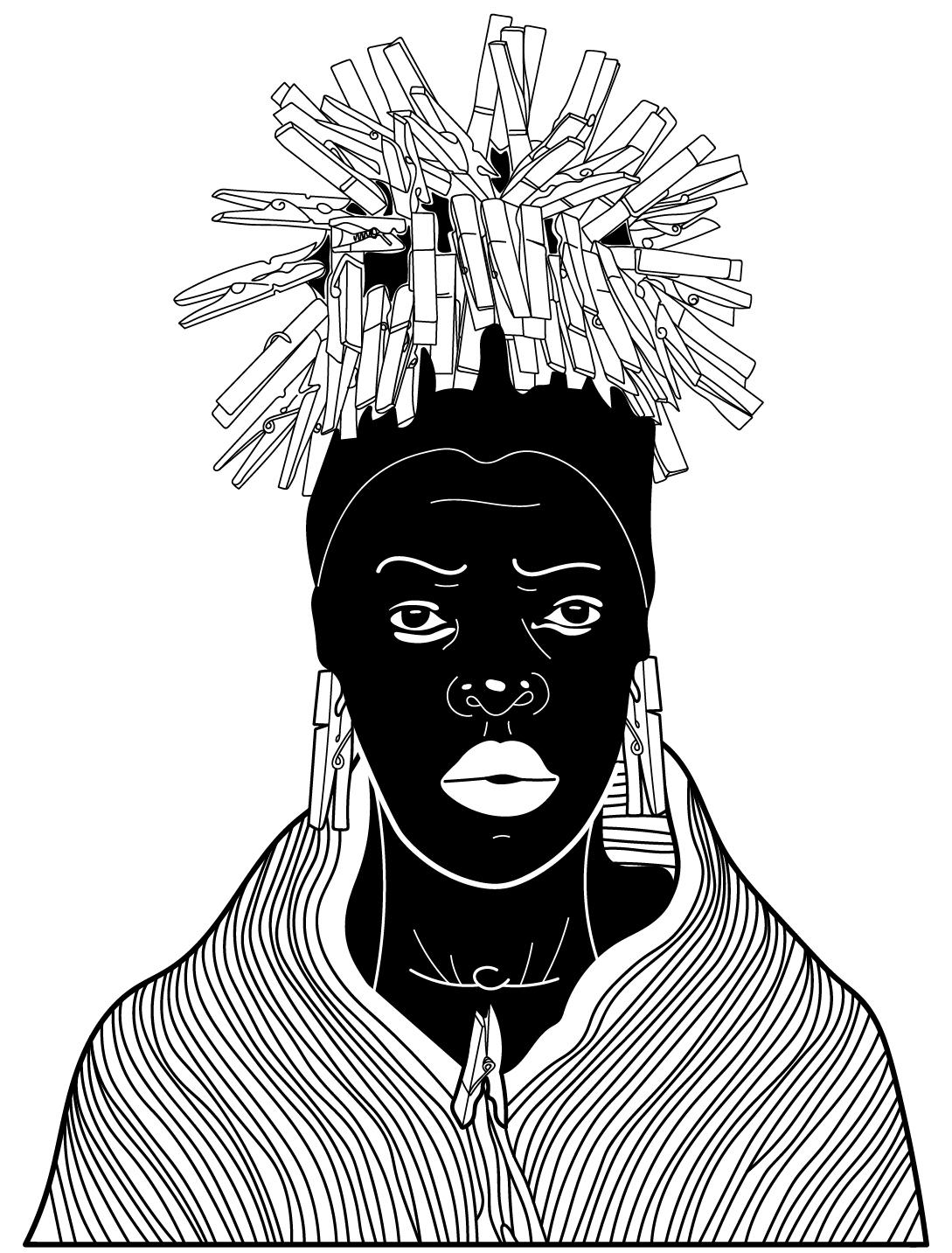

Muholi is a queer “visual activist” exploring why the beauty of people of color and people with non-conforming gender/sexuality identities are not normalized. Muholi captures self-portraits using dress and applied objects, creating raw images of personhood and challenges to norms of fashion, portraiture, and identity. In Bester I, Mayotte (sketched in Fig. 5.7; original here), Muholi created a self-portrait using lighting to spotlight their face with dark complexion contrasting white highlighted lips and eyes. Their face is framed by a coiffure of wooden clothespins, which also serve as earrings and secure a woven rug garment at their chest. The backdrop offers a fuzzy amorphous texture to the photograph, contrasting with the sharp focus and clarity of Muholi’s figure.

This figure reflects a stereotypical European and Euro-American perception of African women’s identity: the ‘tribal’ woman with eccentric adornments. Like African or tribal prints challenged by Yinka Shonibare in “Who Am I?”, this stereotype is embedded with negative connotations of primitiveness, mental simplicity, and, sometimes, ‘savagery.’ Muholi composed this self-portrait very intentionally. As an African female-bodied individual, Muholi knows how global culture views African women. Muholi presents this stereotype as a bold challenge to its perpetuators, including Black people around the world. Muholi’s images ask Black people to consider what these stereotypes mean in their lives and how to change them.

In addition to motivations of global social activism, Muholi’s series from which Bester I, Mayotte derives also comes with personal context. Bester was the name of Muholi’s mother. Bester was a domestic worker, often using clothespins and cleaning rugs. During Bester’s lifetime, being a black-skinned woman in South Africa was never easy. Until the early 1990s CE, South African society was ruled by the policy of Apartheid (literally “aparthood” in the Afrikaans language), segregating indigenous African people (of many different cultures), ‘Coloured’ people (a legal term describing people of mixed ancestry), Indian people (often descendants of slaves/servants from eastern regions), and white people with European heritage (mainly British and Dutch). The populations outside the realm of “whiteness” were oppressed and considered not deserving of the same rights, governed by the minority white supremacist group of European colonizers.

Like during the segregation-era in the US, atrocities of discrimination and violence were perpetrated against all groups not seen to conform with white ‘rightness.’ Bester Muholi lived in a world that often ignored her free will, negated her beauty by normalizing opposite qualities, and reduced her opportunities. Furthermore, people with non-conforming gender identities like Zanele Muholi did not fare well during Apartheid. In 1994 CE, when South Africa passed large-scale human rights legislation ending Apartheid, they were the first country to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation, recognizing various dimensions of sexuality and gender. While these laws were officially set in place, South African society did not transform overnight. Zanele Muholi continued to face similar discrimination as Bester did during Apartheid, along with prejudice against LGBTQI+ sexualities. Today, Muholi uses an artist’s voice to bring awareness to the identities of those that have been and continue to be oppressed, giving face to movements that actively seek equality.

Material beauty and beyond

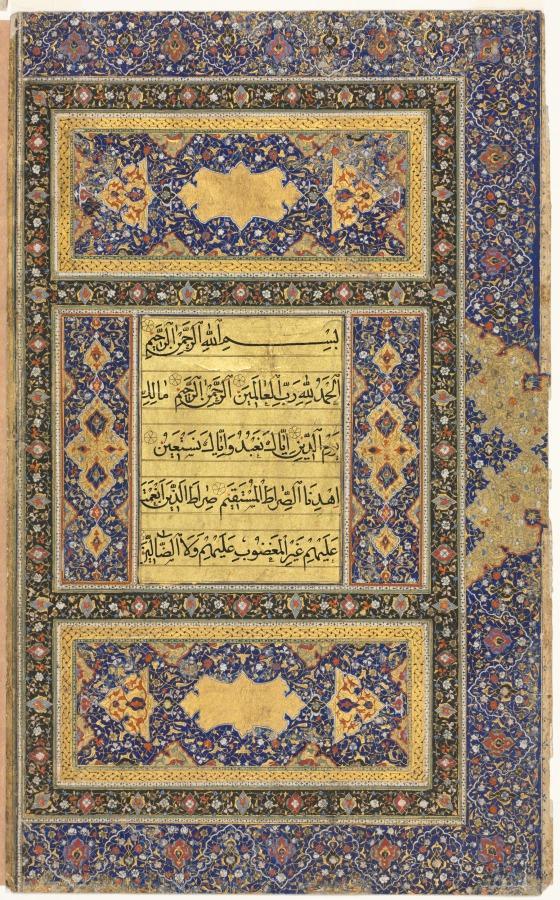

Ideals of human appearance, whether for us mortals or for the divine, often greatly impact lives. In addition, ideals of beauty beyond the human impact how cultures view the world around them, how they create art, and what they value. One artistic practice that exemplifies this grand scale of beauty is calligraphy (fancy writing) in traditions associated with Islam. Let’s consider a Safavid Period Qur’an Manuscript Folio (Fig. 5.8) from present-day Iran (see Fig. 5.1).

Manuscript folios are pages in books that oftentimes have been dismantled and/or disarticulated over time. This folio comes from an immensely decorative version of the Qur’an, employing the technique of illumination (use of gold-leaf to add luster). This single page would have served as one half of a two-page spread at the very beginning of the manuscript. In fact, this part of any Qur’an is the most decorated part and sometimes the only portion of a Qur’anic manuscript with decoration, other than expertly applied calligraphic writing. The balanced, multi-layered borders and box insets on this page create a maze-like effect. These visual mazes are full of polychrome floral and geometric patterns, characteristics of holy arts in Islam. The blue and gold complementary color scheme is a traditional choice while the accent colors of reds, greens, and neutrals add dynamism.

The star of this show is the centered box of Arabic text, written in formal naskh calligraphic script and read right to left. Each letter was formed meticulously using a qalam (reed stylus) according to a system of proportions based on diamond-shaped dots, known as nuqta. Nuqta are only guides and are not inked in final products. The small dots and linear marks around and at the top of the letter forms, known as diacritics, enhance readability and add visual interest. Those of you who have studied text design will probably spot that this text block is justified, meaning aligned to the starting right margin and then spaced to end neatly at the left margin (remember, Arabic is read right to left). Text justification produces geometric blocks of text but often includes irregular spacing, such as the elongated horizontal letter on the right of the first line. This adds emphasis and interest, inviting the reader into this holy Qur’an. Check out “Quantifying the Qur’an” (Brey 2013) for a unique analysis focused on the proportional standards of Qur’anic manuscripts.

Among the artists involved in creating this manuscript, the calligrapher would have been the most important. The production of such exquisite Qur’anic manuscripts typically took place in royal workshops attached to the Safavid and other courts. Design directors, calligraphers, illustrators, and paper makers collaborated in these workshops. These were places of prestige where the rendering of beautiful text held the most value. It is difficult to understand the fundamental importance of calligraphy in Islam if you do not consider Qur’anic scripture itself. In surah (chapter) 96 of the Qur’an, we find this: “Recite in the name of your Lord who created… Who taught by the pen. Taught men that which he knew not.” It is said that Allah speaks to the pen and orders it to write. In this way, there is a spiritual nature to writing and the art of the pen in the earliest periods of Islamic history. This prominence continues to this day. Calligraphy is taught in madrasas (colleges attached to mosques). People who practice calligraphy see it as a religious pursuit that allows them to follow the path of sacredness and purity. In fact, there is an Arabic proverb that translates to “purity of writing is purity of soul.”

All beautiful Qur’an manuscripts are not just produced for their beauty, they are produced as functional objects for people to read. Admittedly, some calligraphy is quite difficult to read (when the aesthetic value is prioritized) but all-in-all Qur’ans are for reading and reciting. In many traditions there are objects that are both pretty and functional. Let’s look at another example. Birdstone (Fig. 5.9) originated in one of the hearts of Native North American culture, what we now call Ohio (Fig. 5.1).

You might look at Birdstone and question our sanity for saying it is functional. But hold onto your hats, folks! At the base of this object beneath the neck of the bird form, there is a hole drilled horizontally through to the back beneath the tail feathers. This hole allowed a carefully crafted piece of wood to be inserted. That wood stick would be attached to an atlatl (spear-thrower used for hunting). Check out “What is an atlatl and how does it work?” (Pettigrew and Garnett 2020) if you are unfamiliar with atlatls. Some scholars have suggested that objects like Birdstone would function as a weight on the atlatl to help propel the thrown projectile farther. Others think that birdstones were used as handles on atlatls that fit well in the palm and metaphorically alluded to flight. There may have been many uses for these objects.

Birdstones were produced with care, via a laborious process of stone grinding (literally rubbing stones together to reduce a raw stone into a designed object). That labor tells us that these objects were special. Furthermore, raw stone was chosen carefully for color and veining by artists to result in the intriguing qualities of light and dark brown streaks seen in Birdstone. The beauty and the practical use of these objects were linked as well through the reference to flight and birds as creatures that can do something humans cannot.

Birds hold particular symbolic significance in many cultures. In ancient Korea, cranes represented longevity and (as water birds) reflected the presence of water sources in the landscape. Can you spot the cranes in Maebyong with Clouds, Flying Cranes, and Children amidst Willows (Fig. 5.10)? White cranes (probably red-crested white cranes native to Korea) fly amidst clouds on the periphery of the central foliated (leaf-like) shape surrounding children playing in a bamboo grove. This vessel was produced by artists of the Koryŏ (or Goryeo) Kingdom of ancient Korea (prior to the Joseon Dynasty and Shin Suk-ju from “Who am I?”).

Koryŏ potters are known for their enhancements upon Chinese techniques to produce greenware pottery, also known as celadon (a European term). Greenware refers to the green-gray color produced from iron-oxide additives in ceramic glazes that emulate the natural color of jade. In East Asia, jade has always been a prominent stone for sculpting spiritual and adornment items, bearing an aura of beauty and magic. Replicating the color of jade in other media infuses its qualities into new form. Greenware ceramics in Korea soared to new aesthetic heights with the invention of the sanggam (“inlaid”) technique. Prior to firing, artists would carve or incise designs into the somewhat dried clay body, creating wells for applying decorative glazes. This technique offers crisper and more vibrant designs than glaze painting.

This is why the imagery is clearly defined in the maebyong. The curvature and swirling patterns of the wispy clouds and the thin lines of sanggam decoration offer complexity to the design. Vessels like this reflect deep investment in artistry (because the sanggam technique takes much longer than typical glaze painting). Further, the various hues of green achieved in this example mimic the variation found in natural jade, and thus the beauty to be found in nature’s multitude. Koryŏ people also may have attributed a kind of beauty to such vessels because as a maebyong (literally “plum vase”), they would hold either long blossoming plum branches or plum wine. In the art world, greenware vessels demonstrating sanggam artistry are synonymous with Korea’s Koryŏ Kingdom. Check out a research essay by Celeste Smith in spring 2022 about a contemporary artist using Koryŏ/Goryeo ceramics in unexpected ways.

In southeast Nigeria (Fig. 5.1), where Igbo peoples live today, an ancient culture known as Igbo-Ukwu holds a similar art historical aura of artistic mastery, connected to detailed bronze sculptures in their case. Igbo farmers in the 1930s-40s CE uncovered ancient bronze arts as they tended yam fields. At first, people weren’t sure how old these bronzes were. After archaeological investigations and radiocarbon dating, scholars determined that these bronzes were the creations of Igbo ancestors from over 1000 years ago, during the 800s-900s CE. Learn about the earliest archaeology at Igbo-Ukwu in “Bronzes from Eastern Nigeria: Excavations at Igbo-Ukwu” (Shaw 1960).

Shell (Fig. 5.11) is a small ornamental container created to resemble the marine triton shell. In addition to the form, what jumps out at you about this object? Your eye probably is caught by the dense and varied decoration. At the widest part of the shell, lattice-like patterning overtakes the surface with grids, concentric circles, and complex netting. As the spiral narrows, there is a consistent pattern of alternating stripes with tightly-spaced lines and dense dots. Representations of crickets and flies pepper the surface as well. At the end of the shell, a finial supports a scene of four frogs being eaten by snake heads. This concentrated imagery of the terrestrial and undersea worlds demonstrates that Igbo-Ukwu artists were strongly observant of the natural world and attendant to cultural symbolism. For Igbo-Ukwu people, insects probably related to agriculture (as pests that must be controlled) and/or to unknown cultural dimensions. Marine imagery probably reflected exotic resources and trade that enhanced the prestige of the leaders who owned such items as this bronze-made shell.

The decorative style of Igbo-Ukwu, exemplified here, has been compared to Rococo furniture and architectural design of the Western Canon. These styles share an ‘all-over’ character, with no surface going untreated. (P.S. the Safavid Qur’an Manuscript Folio shares this ‘all-over’ aesthetic as well.) Igbo-Ukwu bronze artists independently developed an aesthetic of excess and pattern that reflected beauty and prestige in their culture. Dozens of ornamental bronze objects, including Shell, were discovered together near the burial of an ancient Igbo-Ukwu leader. As a high-ranking member of Igbo-Ukwu culture he preferred this style of art, collecting a large number of pieces that eventually were buried with him.

We’ve talked about many objects associated with burials in this chapter. Let’s talk about another one! If you picture where Woman in Ceremonial Dress is from on the Gulf Coast of Mexico, let your mind travel to the northwest. Then, settle your mind in the Chihuahuan Desert (not a desert full of tiny dogs), spanning the modern-day states of Chihuahua and Sonora of Mexico and Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas of the US (Fig. 5.1). The US-Mexico border was totally irrelevant to native peoples of the Americas.

One culture that spanned southwestern New Mexico and northern Chihuahua was the Mimbres (literally meaning “willows” in Spanish). The Mimbres River and surrounding landscape supported many ancient Pueblo cultures (meaning those who lived in congregated adobe structures the Spanish called pueblos). The Mimbres are known for producing pottery, specifically bowls, that were provided to people in death. Bowl with Geometric Design (Fig. 5.12) typifies the ‘transitional’ style of Mimbres vessels, dating to 950-100 CE, focused on geometric motifs depicted with a sense of radial movement. Typically called ‘black-on-white’ ceramics, these vessels demonstrate strong color contrast (with blacks, browns, reds, etc.) and linear abstraction. In this case, large white triangular shapes accentuated with repeating black contour lines and alignments of rhombic shapes appear to swirl around a squarish center, defined with bold lines leading to the primary white border of the bowl. Looking down upon the bowl, we see that the circular rim of the bowl merges with the rotating design and almost looks as if it is spinning. Such interesting abstraction is characteristic of Mimbres vessels, with beauty focused on simple contrasts of line and shape. These bowls also regularly include figures of people and animals centered within geometric patterns.

Another common characteristic of these vessels is the so-called ‘kill hole.’ Seen in Bowl with Geometric Design at the center right of the vessel’s base, a small hole pierces through the clay body, removing segments of the carefully painted interior design. This hole, and the many others in surviving Mimbres vessels, was intentionally created. After a bowl was decorated, and potentially used in daily life, it would be ‘killed’ so that it could accompany a deceased person to their afterlife in a parallel metaphysical condition. The Mimbres believed that special bowls were imbued with spirits, just like living things in nature. Living bowls could not go to the afterlife, so their state must be appropriately modified. Archaeologists call such processes ‘ritual termination.’ Most cultures believe that the afterlife should be a place of rest and harmony, a kind of beauty. Burial offerings should ensure that such otherworldly beauty is attainable. We’ll explore many approaches to the afterlife in “What Happens When We Die?”

Many archaeologists who study the ceramic arts of the Mimbres focus their attention not just on the deceased who took their bowls into the afterlife but the artists that made such bowls. For example, Michelle Hegmon and Stephanie Kulow (2005) studied Mimbres pottery using agency theory. Anthropologists use the term ‘agency’ to refer to the ability of people, and things, to act and influence. Artists have agency to produce artworks. Agency theory also accounts for ‘structure,’ meaning the frameworks in societies that guide, control, and/or constrain how people act and/or do not act. Artists often follow visual styles, like the so-called ‘transitional’ Mimbres style, that structures the artwork they produce. Hegmon and Kulow (2005) highlight the agency of Mimbres potters to innovate outside the boundaries of existing styles and structures in their lives. After the harsh circumstances of colonization for Native American peoples, innovation and experimentation in pottery was revived in the early 1900s CE by artists such as Maria Motoya Martinez and Julian Martinez. As a couple, they produced the famous ‘blackware’ vessels of San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico, modernizing pueblo pottery with their matte unique black-on-black style. Art collectors of the 1930s-40s CE fawned over Martinez blackware, recognizing the beauty of connections between past and present.

Material beauty can be seen in objects that we hold or that populate our graves, or it can be seen in landscapes and vistas curated for reflection in nature. You’ve heard of Japanese rock gardens, right? You may have encountered a miniature sand garden equipped with a rake. Were you enticed to pull the tines of that rake across the smooth sand? That’s the goal of those objects: to give you a break from stressful, daily life for a moment of peace, gently moving sand around in interesting patterns. Karesansui (literally “dry landscape”) represent the original tradition from which those miniature de-stress gardens derive. Primarily associated with Zen Buddhism in the Muromachi period of medieval Japan (ca. 1336-1573 CE and a longer history), minimal rock gardens illustrate landscapes of san (“mountain”) and sui (“water”). As in the Karesansui of Myoko-ji Temple in Kyoto, Japan (Fig. 5.13), mountains are symbolized by large, artfully placed boulders. Light-colored sand or gravel symbolizes water, raked to resemble the ripples of currents. Concentrically rippling gravel pockets appear to bounce off of the boulder mountains and mossy shores of this miniature landscape.

The garden is secluded from distractions. This would have been a place of contemplation and active meditative practice within the Zen Buddhist monastic community of Myoko-ji. Distinct from the Thai Buddhist tradition discussed above, Zen Buddhists of Japan (alongside Chan Buddhists of China) believe that enlightenment can be attained, not just through stillness in seated meditation, but through immediate and completely engrossed action. For example, there are stories of Zen monks reaching enlightenment while they swept their modest hut free of leaves or while cutting wild bamboo stalks with a sharp knife. Enlightenment occurred in these cases because the practitioner was so wholly invested in their task that they transcended thought or preoccupation or desire, demonstrating utter devotion to that one moment.

A garden of stillness, as if a moment of time has been captured, can help a devotee move through their spiritual practice, potentially achieving the transcendent beauty of enlightenment, like the Buddha. These temple rock gardens and the miniature versions sold in gift shops seek to offer psychological respite and inspire calm. In the Zen Buddhist tradition, beauty is calm, clarity, and stillness. Scholars have considered these psychological effects in “Structural Order in Japanese Karesansui Gardens” (Van Tonder and Lyons 2003). Take a moment to consider the beauty of raking pebbles in “Sand and Stone Garden Raking | Japanese Garden” (Fig. 5.14) and de-stress yourself. ![]()

The Wrap-up

We began this chapter by asking what you think is beautiful. We have discussed how beauty has been normalized, represented, and explored cross-culturally over thousands of years. Your opinion on beauty and how it plays a role in your life is your own. Perhaps additional experiences with media or studies of the history of what others find beautiful could lead you to contribute to our definitions of beauty today, according to what you value. To learn more, check out the links to global ideas of beauty and the examples of scholarship that investigate beauty in all its variation.

News Flash

- The Igbo style of arts like Agbogho Mmuo features in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s novel entitled Purple Hibiscus. Adichie is an award-winning Nigerian writer bringing attention to African literature.

- Like the painting by Utamaro, Beauty Looking Back by Hishikawa Moronobu is featured in “Animal Crossing: New Horizons” (Nintendo 2020) as one of the artworks sold by Jolly Redd. Make sure to check whether it is “real” or a fake!

- Want to learn more about Edo Period hairstyles? Check out The Art Institute of Chicago’s video called “Recreating Ukiyo-e Hairstyles” on YouTube. A master of hairstyling, Tomiko Minami, recreates multiple styles seen in historic prints.

- Are you interested in learning how to write and design Arabic calligraphy yourself? Check out Alhamdulillah Arts on YouTube. Start with the basics, “Arabic Calligraphy Tutorial – Lesson 1.”

Where Do I Go From Here? / The Bibliography

Okafor, Chinyere G. 2007. “Global Encounters: ‘Barbie’ in Nigerian Agbogho-mmuo mask context” Journal of African Cultural Studies 19, no. 1 (June): 37-54. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696810701485918

Salter, Rebecca. 2002. Japanese Woodblock Printing. Hawai’i: University of Hawai’i Press.