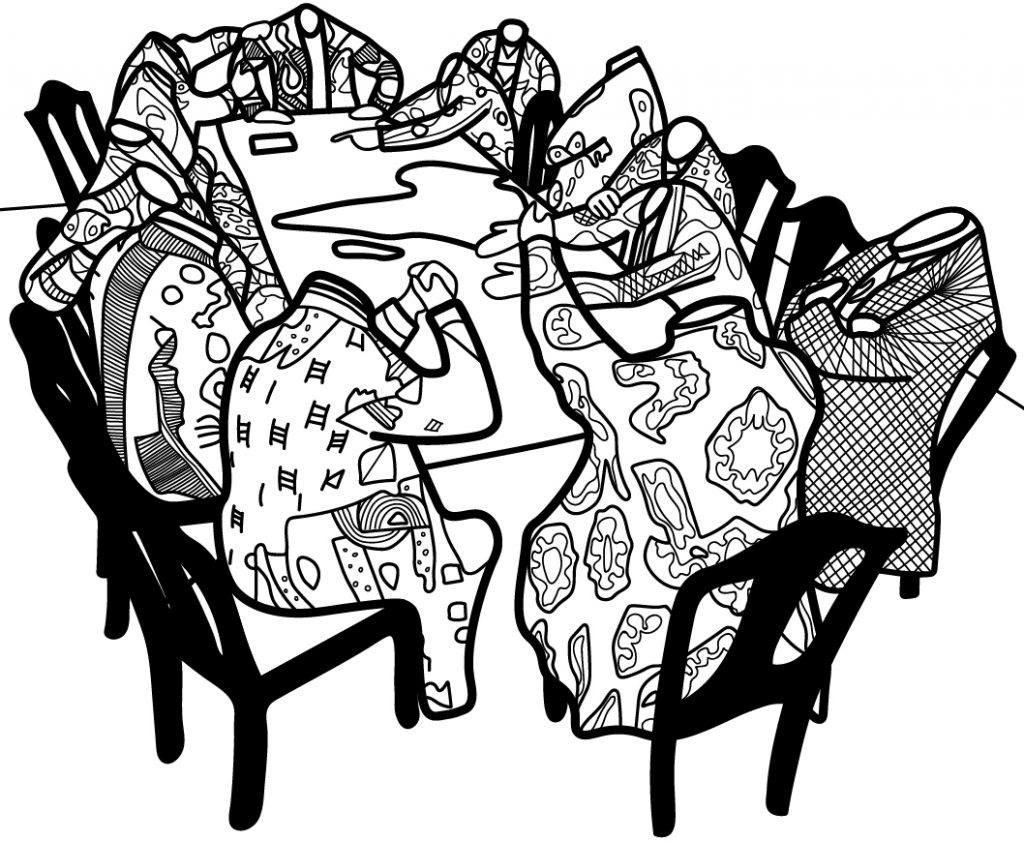

3 Who Am I?

Who am I?

You’ve asked yourself this question, right? We all have. You start wondering: Who am I? Where do I come from? Why am I like this? These questions are natural. In fact, it is concerning if people don’t ask themselves such questions because they demonstrate good mental health practices like self-reflection. We must reflect upon our experiences to make sense of them. This is how we develop ‘selfhood’ or ‘personhood’ (being an individual with our own identity). As we mature, we encounter new experiences and need to catalog them according to our selfhood.

As you grow older you realize that you are not the only one doing this self-reflection. We all start as egocentric infants and need to grow into a “theory of mind.” Psychologists use this term to describe the awareness of others’ individual mentality and points of view, distinct to our own. When you ask yourself the question, “Who Am I?” you are working through a theory of mind of others, to consider where you fit in the landscape of perspectives and experiences.

In studying global arts, one of the first and most important concepts to understand is what we will call the ‘theory of mind of cultures.’ This is the awareness that not only do individual people have their own perspective, and that difference is okay, but that those people are part of cultures that have their own group perspectives. These group perspectives, or cultural traditions, impact individual people. Cultures develop norms (implicit or explicit expectations and standards) that impact how people live their lives and the decisions they make. Norms are founded in normativity (the consensus of desirable and undesirable actions and things) developed independently in all human societies and then sometimes influenced by external groups. Some of the most engrained social norms relate to identity. For example, many societies normalize binary (two-parted) gender identities, featuring masculine men and feminine women. (FYI: Sex and gender are distinct. Sex relates to biology and gentalia. Gender refers to social constructions of identity). In such societies, reflection upon “Who am I?” often starts with situating yourself within such gender norms, or not accepting these norms and challenging your way out of them. But first, let’s consider how we go from being kids to adults and dealing with gendered norms of identity.

Coming of age

Identity formation begins at the earliest ages. Just think of how young children start thinking about potential careers and play doctor or teacher. But, identity formation ramps up significantly as you reach your ‘age of maturity.’ In most cultures, this age is when you become sexually mature (able to produce children). This age also relates to the transition from childhood to adulthood, in terms of decision-making ability and maturity of thought. In many societies, these moments of transition are marked with important ceremonies and rituals, often known as ‘rites of passage,’ ‘initiation,’ or ‘coming of age’ ceremonies that are normalized ways to enter adulthood. Among the historic and contemporary Maasai culture of Kenya and Tanzania (see Fig. 3.1), rites of passage are gendered so that men and women undertake different maturation journeys that prepare them for and mark their different roles as adults.

Young Maasai men prepare to be warriors and protectors of cattle, the primary resource for Maasai livelihoods. Eunoto is an important rite of passage for Maasai men, involving a practice that you have probably seen in tourist or travel journalist photologs: the Adumu or “jumping dance” (Fig. 3.2). This ritual activity is a performance, a competitive demonstration of strength and finesse. The participants demonstrate prowess by keeping their heels from touching the ground as they repeatedly jump and maintain an upright posture. Chanting accompanies the jumping and signifies the pulse of the group.

In the official ceremonies (not those performed solely for tourist revenue), young men visually prepare themselves, sporting ochre body paint, intricate hair braiding, beaded ornaments, and patterned red textiles. In addition to Adumu, the Eunoto (literally “warrior-shaving ceremony”) focuses on the shaving of each warrior’s braids, typically by the warrior’s mother. Combined, all these facets of the Eunoto and Adumu produce a series of spectacles, only heightened (pardon the pun) by the fact that Maasai people are some of the tallest in the world, on average, and can jump higher than most of us can dream. These spectacles present these young men as mature members of society and as having reached the age for marriage and procreation (having babies). Their prowess in the Adumu ceremony and in many other rites of passage within Maasai culture, such as those involving the Rungu (throwing club; Fig. 3.3) symbolize their identity as a man. To consider how globalization has impacted what it means to be a Maasai man, check out “‘Once Intrepid Warriors’: Modernity and the Production of Maasai Masculinities” (Hodgson 2001). Maasai women undergo distinct coming of age rites to prepare them for marriage and childbearing. We’ll expand on this in “Where Do Babies Come From?”

Like the Maasai, other cultures in Africa and around the world practice initiation rites. On the northern coast of Papua New Guinea (PNG) in Melanesia, near the modern city of Madang, so-called Astrolabe Bay is home to a group known today as the Astrolabe Bay peoples (this is the type of unimaginative naming that developed under colonial European rule). Many cultures of PNG are known for carving ancestral figures but the Astrolabe Bay peoples historically focused one of their unique art traditions on an early stage in the initiation of boys into adulthood: circumcision.

Many boys around the world are circumcised (wherein the natural foreskin around the head of the penis is removed). In Astrolabe Bay, this event marks a key point in a boy’s identity and journey to manhood. Boys are separated from the main community around age four and over the next ten years of their lives, they will transform through education in the secrets of manhood and ritual duties. This transformation incorporates circumcision, a painful process often undertaken without anesthetics. Astrolabe Bay boys endure this pain to demonstrate their worthiness.

In ceremonies that celebrate circumcision events, dancers wear Asa Kate Masks (Fig. 3.4), representing the spirit Asa. Carved in local wood, this mask incorporates exaggerated facial features such as protruding eyes with pronounced pupils, ear or horn-like protrusions featuring figures of men, elongated nose and cheeks, and an open mouth. Asa is a malevolent spirit known for frightening and potentially eating the boys who undergo circumcision. They must overcome this fear and Asa’s ‘bite’ (a metaphor of circumcision). The mask sports a gag in the mouth, probably simulating a measure taken to help boys endure the pain. After the circumcisions have been performed and the newly minted men are now prepared to return to their village, a large festival welcomes them home. They arrive on the shoulders of their fathers and uncles, now part of the fraternity among the Astrolabe Bay people. These norms help young boys form their identity.

Aging well

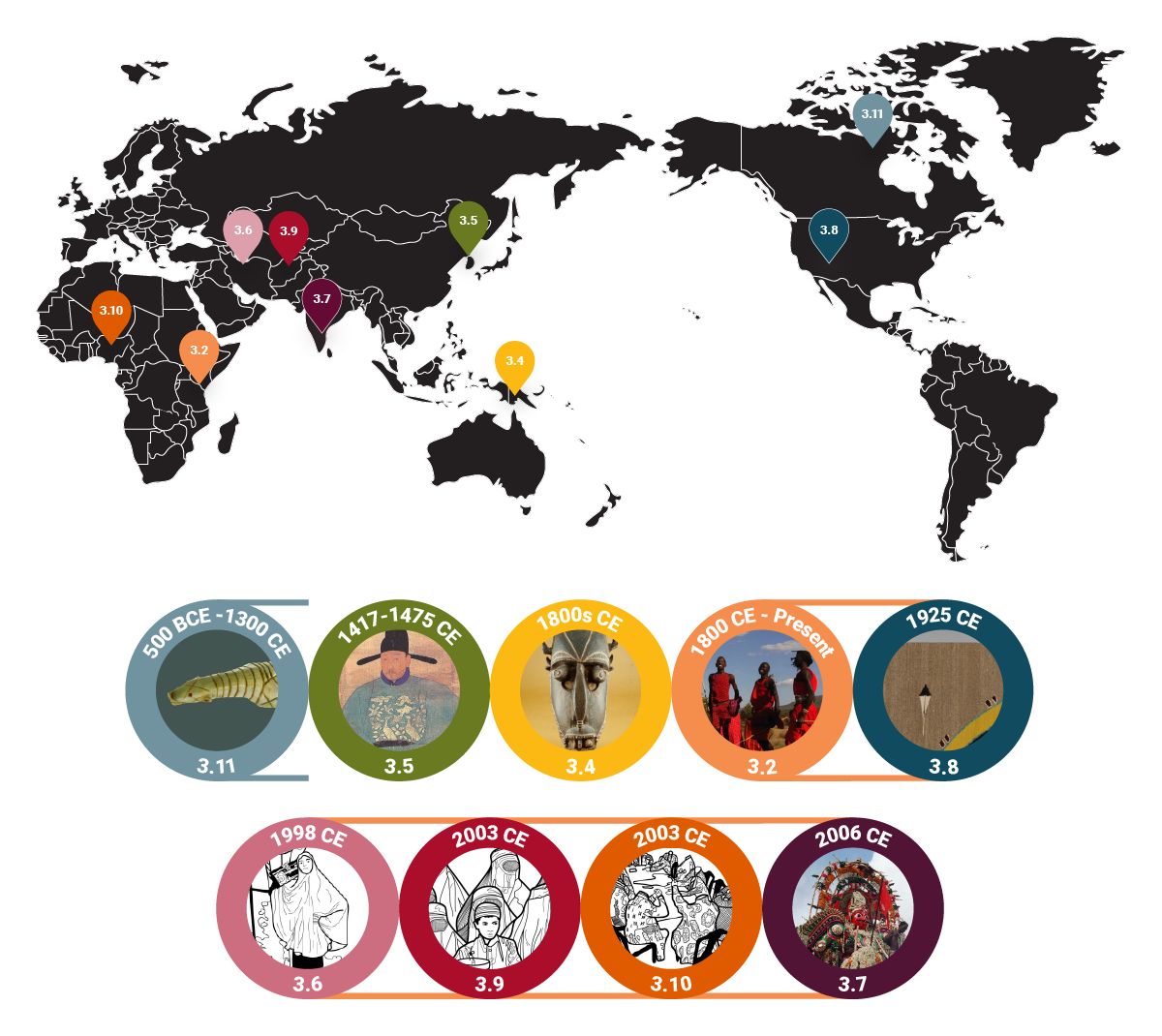

As people age, they often consider “Who Am I?” in different contexts. For example, one may consider who they are with respect to their peers. In positions of power, your peers may be your colleagues and/or your rivals. How do you ‘stack up’ to those around you? We will continue on this topic in “Why Do They Have More Than Us?” but for now, let’s consider the Portrait of Shin Suk-ju (Fig. 3.5) from the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1897 CE) of Korea (see Fig. 3.1). The fact that Shin’s portrait was painted in this manner tells us a lot about his identity. He was a civic official/bureaucrat of the Joseon court. He was esteemed by the Joseon King for his academic achievements and for honorable deeds. He aged well.

How can we deduce these facts about Shin Suk-ju? Let’s talk about Confucianism, or in this case, Neo-Confucianism. In ancient China, probably during the Zhou Dynasty (ca. 1046 -256 BCE), a scholar (probably) named Kǒng Fūzǐ and/or Kǒng Qiū (supposedly) expanded upon a pre-existing social philosophy that was passed down through generations, eventually becoming codified as Confucianism (Confucius is the anglicized way of saying his potential Chinese name). You may have noticed the multiple probablys and supposedlys in that previous sentence. Scholars can’t be sure when (or whether) Confucius lived or much about him other than the way the ideas of his intellectual group eventually coalesced into a social and moral doctrine followed by many rulers of ancient and historic China, Korea, and Japan. Confucianism eventually developed into a religion focused on order in society, which is ultimately founded in family structures, particularly the hierarchical structures of elders and primacy of men’s identities in family life. These hierarchical structures are classed under the term “filial piety.” Younger people and women must respect the hierarchy (relationships of power and authority) in their family. The hierarchy that rules a family, maintaining order and stability, is a microcosm for the whole society and the government. If society is to be harmonious and the government is to be effective, hierarchies must be respected and sustained. To learn more about the scholarship on Confucianism, check out Manufacturing Confucianism (Jensen 1997). In fact, Jensen is one of the scholars who supports the claim that Confucius wasn’t a real person but developed as a mytho-historical idea through writers after the Zhou Dynasty period.

Confucianism is considered a rationalist approach to philosophy and a religion incorporating spiritual elements such as the worship of ancestors – the ultimate elders. Other schools of thought such as the metaphysical (transcendent and/or concerning abstract ideas beyond matter) religion of Daoism and the imported (from India/Nepal) spiritual system of Buddhism began to compete with Confucianism for sway among rulers and the general population. Starting in the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE) of China, scholars began to reform the original Confucian tradition into what we now refer to as Neo-Confucianism. This new trajectory incorporated more metaphysical components to ‘answer’ the competitive landscape of Daoism and Buddhism. Thus, Neo-Confucianism served political, social, and spiritual needs as a continuation of the age-old Chinese tradition of hierarchical structure. Confucianism and later Neo-Confucianism became very influential in Korea, Japan, and other cultures around Asia. The Joseon Dynasty of Korea actually rejected Buddhism (the official state religion of the previous Koryŏ Dynasty) in favor of Neo-Confucianism.

Now, we’re back to Shin Suk-ju. Like good (Neo-)Confucianists, the Joseon court was organized as a large civic bureaucracy with many ministers, officials, and lower-level bureaucrats. To distinguish between the ranks, officials commissioned silk robes with ‘rank badges’ embroidered front and center on the chest. What do you notice about Shin’s rank badge? The luxurious gold thread plays nicely against the teal silk, right? What about the symbolism there? Notice the clouds, plants, and the two birds at the bottom of the design? Those are peacocks. Birds have always held important symbolism in Korean arts; we’ll discuss this more in “What is Beautiful?” Peacocks in Shin’s rank badge present his identity as a civic official, one of high rank and status in the court bureaucracy. Documents from this period also help us to learn that he eventually ascended to Prime Minister of the Joseon court.

This portrait also demonstrates that Shin wasn’t just any peacock-level civic official. He became a ‘meritorious subject’ of the Joseon Royal Bureau of Painting. This portrait was commissioned by the Joseon King to honor Shin for a valued decision and/or job well-done, potentially associated with Shin’s work creating the modern Korean alphabet known as Hangul or his work on royal painting collections. Check out “Sin Sukju’s Record on the Painting Collection of Prince Anpyeong and Early Joseon Antiquarianism” (Jungmann 2011) for more on that topic. Portrait of Shin Suk-ju would be presented to the official’s family and eventually would serve as an ancestor image, to be worshipped according to the Confucian tradition. In this way, Shin’s portrait represents his status as an elder. Given all these facets of his identity, Shin sat at the top of his family hierarchy and near the top of the social hierarchies in Joseon Korea.

Gender and sexuality

For a distinct contemporary perspective, let’s consider Muslim culture in modern-day Iran (see Fig. 3.1). Iranian photographer Shadi Ghadirian questions “Who Am I?” in her Qajar series presenting sepia-toned, historic looking portrait photos with unexpected twists. In Ghadirian’s Untitled (sketched in Fig. 3.6, original here), a veiled woman standing in front of an old-timey portrait backdrop holds a large boombox on her right shoulder and poses with a strong hand on her opposite hip. Other photographs in the series show veiled Muslim women, sometimes in historic garments while wearing sunglasses, drinking from a Pepsi can, vacuuming with a modern appliance, or posed with bicycles. Ghadirian juxtaposes historic and contemporary elements to challenge how non-Muslim viewers see Muslim women, especially Muslim women who chose to veil. Most Americans often see veiling practices as historic holdovers from previous eras and see veiled Muslim women as stuck in the past and thoroughly non-Modern. As a Muslim woman herself, Ghadirian asks, why can’t a veiled Muslim woman carry a boombox or ride a bike? Importantly, while these photographs poke at stereotypes of Muslim women held in the United States and around the world, Ghadirian’s work also intersects with debates within Muslim communities concerning whether religious practice can interface with modern practices and/or attitudes.

To consider Ghadirian’s work fully, we have to understand Islamic views of gender. In Islam, binary gender identities are the norm, while other gender identities are often illegal. The Qur’an (the holy book of Islam) and the Hadith (sayings of the Prophet Muhammed) provide guidance on the expectations and social roles of men and women. In the late 1970s CE, a surge of public support for conservative Muslim values rallied against the rule of Persian Shahs (Kings) in Iran. The Shahs were focused on westernization, modernization, and did not prioritize Islam as conservative communities wished. In 1979 CE, the Islamic Revolution changed the political and social landscape, officially transforming the country into the Islamic Republic of Iran with a theocratic constitution (a political system focused on the leadership of religious officials who rule in the name of their God/gods). Elections in Iran have brought many men to power, maintaining conservative Muslim values and laws. These leaders also sanction violence against dissenting social minorities and perpetuate unequal human rights.

Despite their important role in the revolution, women do not receive equal rights under Iran’s constitution. There have been movements towards women’s rights in Iran but women are subject to required veiling in public (even if veiling is not part of their personal choice), segregated educational standards, strong domesticity expectations, and, sometimes, sexual assault that goes unpunished. It is important to note that this is not the case in all countries with large Muslim populations or where Islam is the official state religion.

As a social movement, the Iranian revolution rejected European and Euro-American influences, including modern technologies, American brands, and popular culture. As Ghadirian depicts, boomboxes were imported items purchased by wealthy Iranians flirting with the illegality of European and Euro-American materials. Women would certainly not publicly present themselves with such items. Veiled women could not ride bicycles in public either given social codes of women’s modesty, even if their family was wealthy enough to own one. Under the laws of their country, based in their faith, they are not permitted to pursue the activities that they may wish to. Thus, their identity feels fractured. They are Muslim, as faithful believers, and they are women, restricted in their social freedoms. Ghadirian’s Qajar series challenges the norms assigned to contemporary Muslim women in Iran from her own point of view (which we must recognize may differ from other Muslim women in Iran). Check out “Restaging Time: Photography, Performance, and Anachronism in Shadi Ghadirian’s Qajar Series” (Heer 2012) to learn more.

Many people challenge norms and sometimes eventually deconstruct and/or change norms. In many cases, when men display traits normalized for women or vice versa, those people are viewed as ‘different,’ ‘abnormal, or, sometimes criminal. In Europe and Euro-America today, there is a spectrum of such non-norm gender identities, some that are not so upsetting to the norms and others that ruffle many more feathers. For example, girls who identify as ‘tomboys’ are not necessarily so ‘different’ these days. But, what if your identity lies on the other side of the spectrum and you don’t ‘fit in’ ways that are more challenging to the established norms?

Non-binary gender and sexuality identities often lack normalization. People who identify as transgender or non-conforming in Euro-America, for example, often live at the margins of society because of the perceptions of others. In global societies, non-binary gender and sexuality identities have long histories and sometimes are normalized. Let’s consider a long-established transgender identity in South Asia is known as Hijra (or Kinnar) (check out The Truth about Me: A Hijra Life Story [Rēvathi 2010] for a personal narrative).

Most Hijra grow up as men then at some point in their life choose to live according to women’s social roles, potentially undergoing removal of male sex organs. Some Hijra are born intersex, meaning with reproductive or sex organs atypical for their ‘presenting’ gender (which is often prescribed by parents at birth). There are references to such identities in ancient texts associated with Hinduism, indicating the longevity of this non-binary gender tradition in South Asia. FYI: We will discuss Hinduism in depth in “What is Divine?”

Despite this longevity, Hijra have not fared well in Hindu social life, often choosing to live in secluded spiritual communities and/or working as sex workers. Despite this marginalization, the Hijra community of south India celebrates its history and spiritual ancestry in the Koothandavar Festival, featuring images of the Hindu mythical hero Aravan (Fig. 3.7). The culminating event of the festival is the chariot parade of a monumental and highly decorated sculpture of Aravan, featuring thousands of strung flowers and brightly painted features. Hijra from around India assemble to ritually marry Aravan, as Lord Krishna did after transforming into a woman known as Mohini in the mythology. Then, according to the legend, Aravan is sacrificed. In this story, Lord Krishna represents the transgender experience. This ceremony recognizes the place of Hijra in history, and is a performance of their role in society. By 2014, all South Asian governments had officially recognized Hijra as a “third gender” protected under the law. Unfortunately, the Hijra who work as sex workers still lead criminalized lives because “homosexual acts” remain illegal. Despite these continued hardships, the Hijra community has more access to education and career opportunities now that their identity and their rights as people are normalized by legislation.

Another normalized non-binary gender is the nádleehí of the Diné (Navajo), a Native American culture that eventually settled in what is now the southwest US (see Fig. 3.1). Within the multiple gender traditions of the Diné, nádleehí identify as female-bodied or male-bodied, taking on norms of a woman or a man based on the embodied gender, but also occupying a different social space altogether, as discussed by Carolyn Epple (1998) in “Coming to Terms with Navajo “nádleehí”: A Critique of “berdache,” “Gay,” “Alternate Gender,” and “Two-Spirit.” For example, historic Diné artist and healer Hosteen Klah could traverse the gendered domains of weaving (gendered for women) and singing/healing (gendered for men) as a nádleehí. Sandpainting Tapestry (Fig. 3.8) exemplifies these dual roles.

Firstly, it is important to note that many Diné people do not wish their mythologies and spiritual knowledge to become public, thus the display of Diné artworks is problematic. Sandpainting Tapestry by Hosteen Klah is part of the Art Institute of Chicago collection and on their website they offer a full image if you wish to view it. With respect to Diné traditions, we choose not to illustrate the full image here. Let’s focus on Hosteen Klah as a person and artist, versus the symbolism represented in the tapestry. Klah was a trained Diné healer who performed many ceremonies focused on chanting, spiritual illustration in sandpainting, and medicinal knowledge to aid recovery from illness. According to tradition, such sandpaintings were destroyed to ensure that the powerful spirits invoked through them did not overwhelm this mortal world by their continued presence. Thus, the sandpaintings themselves are gone. However, they sort of survive because as a nádleehí, Klah could translate sandpainting designs from memory into woven tapestries, a preservable artform. These weavings are the only surviving record of Klah’s healing role and serve as a testament to the normalization of multiple genders in Diné society.

Another non-binary gender that is relatively normalized in Afghan society was highlighted in the 2003 film “Osama” by Afghan filmmaker Siddiq Barmak. Osama is the name taken on by a young girl who must become a bacha posh to ensure the livelihood of her family during the early part of the authoritarian Taliban regime in Afghanistan (see Fig. 3.1). Bacha Posh literally translates from Persian to “dressed up as a boy” and describes daughters of families without sons who must take on the role of a son, living in public as a young man. Under Taliban rule, women were often forced to remain home and were persecuted if seen in public, especially when without an escort. In the opening scene of the film, a crowd of veiled women in long blue burqas (full-body veils as seen in the Fig. 3.9 sketch and in the original film poster) protest on the village streets. They hold banners protesting for their right to work outside the home, some as widows who need to provide for their family. Eventually, members of the Taliban military arrive, chasing the protesting women, spraying many with painful streams of water, and arresting several women by locking them in cages. This is the circumstance that the unnamed protagonist and her mother find themselves in, without a father/husband or brother/son to provide income and accompany them in public. Thus, the young girl cuts her hair and takes on the clothing of a young boy, creating the character of Osama. Unfortunately, Osama is found out by the Taliban, who do not see the Afghani tradition of bacha posh as acceptable, and her fate is not a happy one.

Osama is remarkable for many reasons (but not because the name of the film happens to coincide with the name of Al-Qaeda terrorist Osama Bin Laden). This was the first film to be completely produced in Afghanistan since the Taliban take-over in the 1990s CE. Aesthetically, the film is somber and dark with some flashes of color such as the blue burqas. In tone, the film is realistic, sad, and revelatory for European and Euro-American audiences. In addition, all the actors were amateurs from Kabul, ‘discovered’ by Barmak. Given all of these important factors, this film received multiple accolades from the independent film industry including awards from the Cannes Film Festival and the Golden Globes. While Osama is not a story of hope for bacha posh in Afghanistan, it portrays this cultural tradition with realism and purpose, bringing light to one global example of where gender norms do not fit global stereotypes and have been persecuted by totalitarian regimes. Read about another personal story in “I’m a Woman Who Lived as a Boy: My Years as a Bacha Posh” (Nordberg 2014). We’ll consider the Taliban again in “Why Do People Take What Doesn’t Belong to Them?”

Big picture

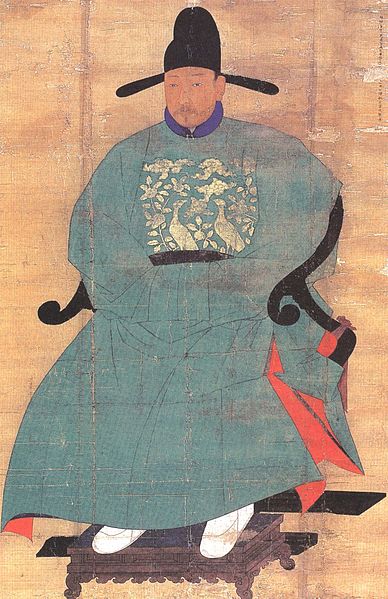

Over time, we might ask ourselves “Who Am I?” in the grander scheme of things, in the large-scale patterns of societies, economies, politics, and cultures that mingle? Contemporary artist Yinka Shonibare asks such questions, focused on his heritage as a British-born, Nigeria-raised Black man. In the early 2000s CE, Shonibare started interrogating the relationships of European imperial expansion across Africa (and other parts of the world) and Africans as people in spaces that did not offer equality.

Scramble for Africa (sketched in Fig. 3.10; original here) is one of a series of life-sized installations using the imagery of Victorian-era stately interiors, such as dining rooms, for staged and highly theatrical scenes. Headless figures gesticulate around a table, at the center of which sits a map of Africa. The gesticulations are territorial claims: “I get this part and you get that part.” These men, perceived as Europeans, are dressed in finery that denotes their station in life. They are wealthy and apparently that wealth gives them the right to stake claim to a continent already home to millions of people (please, note the sarcasm). Shonibare describes the mindset he portrays: “I wanted to represent these European leaders as mindless in their hunger for what the Belgian King Leopold II called ‘a slice of this magnificent African cake’” (Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth 2013). We’ll talk about Leopold II in “Why Do They Have More Than Us?”

The bright, colorful, and patterned clothing is important. The fabrics are often referred to as ‘African’ or ‘Tribal’ prints but Shonibare learned that such fabrics are actually wax-printed Dutch knock-offs of batiks, an indigenous type of cloth traditional in Indonesia. In the early 1600s CE, the Dutch East India Company established trade with India and Southeast Asia, eventually establishing colonies like Indonesia. Attempted sales of these ‘Dutch wax’ knock-offs were not successful in Indonesia (because Indonesians wanted traditional batiks), so the Dutch sent the knock-offs to West Africa. They became popular there and soon the history of these fabrics was conflated into ‘African’ or ‘Tribal’ labels.

We cannot ignore the human rights dimensions of Shonibare’s artwork. Are you asking yourself, “where would Shonibare’s Nigerian ancestors be in this scene?” They would be serving around the table or in a much worse situation as slaves to these seated men. Shonibare has stated that these works that exude historic character are metaphors for his feelings on imperialism and materialism still undertaken and experienced today, such as through American brands like NIKE. Shonibare asks “Who Am I?” in this confluence of resources exchanged back and forth across oceans: oil, shoes, iphones, human beings. He wants you to ask yourself who you are in these networks of exchange. How do you contribute to the perpetuation of inequality, pollution, injustice?

We should mention two other facets of Yinka Shonibare’s identity. In 2019 CE, he was awarded the honorific title Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire to recognize the importance of his work. Also, since he was 19, Shonibare has used an electric wheelchair due to a paralyzing illness. He produces some of the most acclaimed artworks on the contemporary art scene today. He is an artist asking us to think about the past and the present. To hear from Shonibare himself, check out an interview in “Yinka Shonibare in Conversation” (Downey 2004). To read about perceptions of Shonibare’s work and how it relates to the work of other artists, check out Chinamerem Ahuchaogu’s research essay submitted in Spring 2022, focused on an interview with his grandmother who grew up in Igboland, Nigeria.

Let’s take one more big leap to consider our question of identity. Have you ever asked yourself, “Who am I, a tiny human, compared to this huge planet earth?” For the people now referred to as the Dorset culture of present-day Arctic Canada (see Fig. 3.1) (we don’t know what they called themselves), the idea of human humility and the bigness of nature was a norm of their identity. Before the Inuit peoples (formerly known as Eskimo) of the Canadian Arctic and Alaska, the Dorset lived in this harsh environment, adapting to cold conditions and seasonal change. They were hunter-gatherers focused on storing enough resources to keep comfortable over the coldest months. They were very good at this, especially hunting sea mammals with harpoons. These practices naturally taught them about their environment and shaped their identity.

Dorset artists created miniature ivory carvings of polar bears (Fig. 3.11) that reflect this identity. Dorset polar bear carvings often represent the bear in the position called ‘laying, still-hunting.’ In a semi-relaxed horizontal posture, the polar bear floats/lays in the water waiting to spring into action to catch sea mammals like seals, walruses, and narwhals. ![]()

Importantly, these are the same animals Dorset people hunted. Dorset artists obviously observed polar bears while hunting and probably identified with them as successful hunters. This type of connection to nature is rare in European and Euro-American societies because patterns of consumption and resource extraction distance people from animals and nature. Most people probably associate polar bears with Coca-Cola branding or with social media pictures of melting icebergs. The Dorset saw themselves in nature. If a Dorset hunter was to ask themselves, “Who Am I?”, they may have reflected “I am like the bear.”

You may also be asking why there are incised lines on the polar bear carving. Scholars do not agree on the significance of these lines. The most interesting hypothesis asserts that these lines imitate the skeleton beneath the bear’s fur and that this skeletal reference is another bear-human connection. Archaeologists rarely find bones associated with the Dorset people. They rarely find any burials at all. Some think that Dorset mortuary practices involved dismembering the dead and sinking the fragments into the sea, becoming food for sea animals. Illustrating the skeleton on the polar bear carving is a way to visualize the cycle of life and death, hunting and consumption, and potentially linking polar bears to spiritual systems of Dorset culture. Many scholars suggest that these carvings represent profound spiritual connections between bears and people. Learn more about archaeological excavations that support such interpretations in “Dorset Shamanism: Excavations in Northern Labrador” (Thompson 1985).

The Wrap-up

Don’t stop asking yourself “Who Am I?” because that’s how you remember where you’ve been and figure out where you want to go. As you continue your studies of global arts and you meet new people, remember the theory of mind. Everyone is thinking, just not thinking the same as you. That’s a good thing most of the time. Your identity is valuable but isn’t singular. You are part of many collectives, even if they are small ones. To consider global identities more, check out the media recommendations below. Then, make your way into the scholarly literature on these topics by checking out the articles and books cited. You can contribute to these conversations!

News Flash

- Are you interested in fashion? Check out the article on slate.com called “The Curious History of ‘Tribal’ Prints” to see how Yinka Shonibare’s work relates to Gwen Stefani and New York Fashion Week.

- The BBC made a documentary film about Hijra and featuring the Aravan Festival called “India’s Ladyboys.” (Note that “Ladyboy” can be considered an offensive term.)

- The animated film The Breadwinner (2017) by Cartoon Saloom highlights the story of a bacha posh, based on the novel by Deborah Ellis.

- Are you a fan of K-Drama? Shin Suk-ju was featured in a South Korean KBS2 television period drama called The Princess’ Man produced in 2011.

Where Do I Go From Here? / The Bibliography

Downey, Anthony. 2004 “Yinka Shonibare in conversation.” Wasafiri 19, no. 41: 31-36.

Rēvathi, A. 2010. The Truth about Me: A Hijra Life Story. New Delhi: Penguin Books.