14 Why Do I Have to Do What You Say?

Why do I have to do what you say?

As children, many of us want independence and freedom so we ask why we always have to do what our caregivers say. Then, as we get older, we may disagree with family members, political leaders, or institutions that make decisions that affect us. In response to these disagreements we can practice defiance, or resistance to the authority or expectation that we dislike. In the arts, defiance can be overt and clear or it can be subtle and hidden.

In “Why Do They Have More Than Us?”, we considered social hierarchies and social disparity. We focused on kings, emperors, and colonizers often at the top of a hierarchy. Kings and colonizers don’t want to topple those hierarchies down. They want them to stay in place for as long as possible, because that’s how they stay in power. Those who defy social hierarchies choose to resist the disparity, actively commenting on it and making change. This sort of defiance is often entangled in postcolonial movements of recent centuries and decades, wherein organizations or whole societies want change from the colonial order and try to determine what their independent society will be like. Let’s start with resisting an established art style and then move into expressions of social and political defiance.

Making your own style

Have you ever heard someone referred to as ‘eccentric’? Generally, this means that they don’t follow the rules or social norms, and others think they are odd. Many artists have been called eccentric. A group of Japanese artists of the Edo period have been labeled “The Eccentrics” by recent scholars because of how much their style and content diverged from the norms of their day. One of the most famous of this group was Soga Shōhaku, who favored historic painting styles reaching back hundreds of years to the Muromachi period (the same time when the Karesansui in “What is Beautiful?” was created). Shōhaku is described as “unconventional” (DMA 2017) or as a “madman” who produced “weird” imagery (Editors 2021). Lions at the Stone Bridge of Mount Tiantai (Fig. 14.2) is an excellent example of his style.

This hanging scroll produced with ink on silk is almost 4 feet tall, a scale that impacts the viewer immediately. The subject matter is even more impactful. A lion overlooks a deep cliff near the center of the painting. A huge arch rises above the lion, with jagged cliffs receding in the distance. As we look closer, we realize that the lion at the center is not alone. There are hundreds of lions in a frenzy of movement. Some lions have already fallen from the topmost arch, descending into an uncertain mass of clouds.

Shōhaku depicts a narrative here, but in a very surreal way. The original story centers on a lioness who is determined to find which of her cubs are the most resilient. The lioness throws her cubs from the cliff’s height to test them. ![]() If they survive the fall or find a way to avoid it and return back to her, they are part of the deserving, resilient bunch. Now we see why all the lions are racing up this terrifying landscape!

If they survive the fall or find a way to avoid it and return back to her, they are part of the deserving, resilient bunch. Now we see why all the lions are racing up this terrifying landscape!

As the title shows, Shōhaku illustrated this narrative with reference to an actual place: Mount Tiantai in Zhejiang Province, China. This area features a natural stone arch over a waterfall. The Tiantai landscape is dramatic. The arch could serve as a bridge, if it wasn’t so perilous to cross. But a bridge to where, you ask? Legends associated with the Tiantai sect of Buddhism say this is a bridge to paradise.

This supernatural landscape is uniquely imagined by Shōhaku. The cliff faces are impossibly sharp and high. The arch looms menacingly above the lions, almost determining their fate by its very appearance. Shōhaku exaggerates the verticality of the hanging scroll by elongating the cliff forms and driving our eye from the very bottom right corner to the top center quickly (once our concern for those lion cubs begins). The circular cloud edges and organic shapes of the lions’ bodies offer contrast to the highly geometric landscape features.

Shōhaku employs many mainstays of traditional Chinese painting, which was very influential on Japanese painting styles: mountain/water combinations, middleground mist, identifiable brushstrokes, and varied tonality. But his offering is unique and did not follow the norms of Japanese painting during his time. Some scholars suggest he simply did not like Edo period painting styles, preferring historic styles aesthetically. Some scholars suggest he was a rebel, bent on rattling cages and defying the status quo. Whatever the case, he certainly had a vision and is a clear example of how an artist can ask themself “why do I have to do what my painting master told me to do?” To learn about how Shōhaku and “the lineage of eccentrics” influenced contemporary Japanese artists such as Takashi Murakami, check out “‘Lineage of Eccentrics’: The Popularization of Art History, or Rewriting Japanese Art History” (Choi 2019).

Social defiance

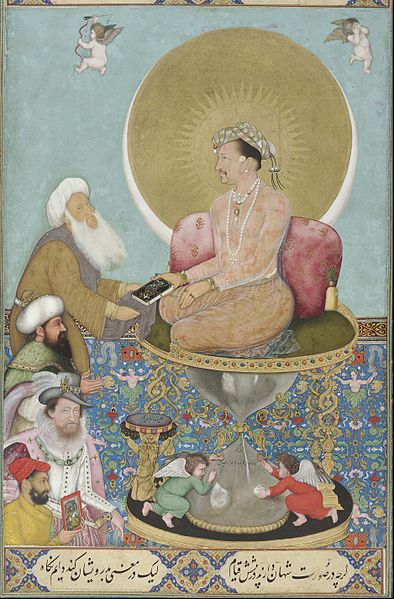

Remember Abkar from “Why Do They Have More Than Us?” Remember Basawan’s swirling composition? Mughal miniature painting continued after Akbar’s death, when his son, Jahangir, took the throne. Jahangir was like his father in some ways but instructed his court painters to depict him differently than his father did. Akbar preferred action scenes and drama. Jahangir preferred metaphorically significant depictions of his position, in defiance of social expectation.

Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Sheikh to Kings (Fig. 14.3) is another Mughal miniature painting designed to emphasize the emperor, dazzle the viewer with color, and send a message. Starting from the top we see a delicate border and two floating nude cherubs, one covering its face and the other with a bow and arrow. Yes, cupid makes an appearance in Mughal India! Below the cherubs, our eye is overpowered by the huge circular halo and starburst centered on a seated man’s head. Three guesses who that is!

Yes, that is Jahangir, the resplendent emperor. He wears an intricate fabric headwrap, jewels, and sheer garments. He rests against a plush pillow on a circular throne. The throne platform is supported by an hourglass, framed by intricate gold and jewel-encrusted designs. Another set of cherubs collaborate at the base of the hourglass inscribing written praise of Jahangir. Next to the cherub in green robes, there is a footstool that Jahangir would use to step into and out of the throne. It is elaborate and includes an inscription as well. More on that in a moment.

You’re probably wondering who the four figures on the left are. Starting at the top, we see an old man with a long white beard in a plain white head covering, wearing plain brown robes. Below him, we see a less aged man with his hands together, wearing a regal green robe and what appears to be a fur head covering. Unlike all the other figures, the third man looks out at the viewer. He wears garments very distinct from the others. His feathered hat, pink cape, and buttoned shirt frame his haughty face, sporting a wiry beard. His left forearm rests on the hilt of his sword. Lastly, in the bottom left corner, we see the youngest man, bearded and wearing a red turban with a yellow robe. This young man holds a book.

Jahangir also holds a book. He is interacting with the old man at the top left, giving the book to him. This generous act is an important part of the message of the painting. The position of the gift receiver is as well. This old, bearded man is a Sufi (a Muslim person who practices a particularly devout life focused on mysticism). The other men below him, dressed to distinguish their high status, do not receive anything from Jahangir. The green robed man is probably an Ottoman Sultan who would visit Jahangir’s court (or send officials to visit for him). The pink caped man is probably James I of England, the successor to Queen Elizabeth I. To learn more about European visitors to Jahangir’s court, check out The Mughal Padshah: A Jesuit Treatise on Emperor Jahangir’s Court and Household (Flores 2015).

Jahangir does not dote on kings. He prefers to interact with the holy man. From the emperor’s seat, this is a form of social defiance. He is defying the expectations that at his level in society, he should engage with peers ruling other lands. Instead, this painting demonstrates that he values the common man more than foreign emperors and that he relates more to a devoted religious person than to powerful politicians.

Yes, we’ve not identified the fourth man yet. Well, he’s the person who made this painting possible: the designer! His name is Bitchitr. We know this because the inscription on Jahangir’s footstool is Bitchitr’s signature. Bitchitr also hints at his occupation by holding the book, an example of the final product that would contain all his separate miniature paintings like this one, originally intended as folios in a book like the Akbarnama. We can know one more thing about Bitchitr: he is Hindu. His yellow robe clearly indicates that he practices Hinduism in Muslim-controlled Mughal India. Early Mughal leaders fostered pluralism in their empire, for Sikhs, Hindus, Muslims, Christians, and others, a topic which we will explore more in “Can We Live Together?”. These leaders defied the norms of religious control and oppression often seen in territorial empires.

Political defiance, then

Leaders like Jahangir are often the most well-placed people to defy social, religious, and political norms because of how much power they hold. Let’s consider some other politically-charged examples of defiance. First, have you ever thought of a horse as a symbol for your government?

If you lived in ancient China and participated in scholarly culture, you certainly would have answered yes to that question. Throughout Chinese history, especially in periods such as the Tang dynasty (when the Equestrienne figure in “What is Beautiful?” was made), horses served as icons for the government, its impact on people, and the status of society as a whole. The horse icon was particularly important in the scholarly community made up of government officials, men of leisure, and other intellectuals. Talk about high status and hierarchies!

China, like most countries, changed hands many times and consisted of many different ethnicities. In 1279 CE, a new era of government in China, powered by an invading force, was established under the Yuan Dynasty. Can you guess who that invading force was and what obstacle they scaled to conquer China? Yes, we’re talking about the Mongols from the Eurasian Steppe (present-day Mongolia) invading over the Great Wall of China. (FYI: Prior to the Ming Dynasty that succeeded the Yuan, the Great Wall was not as ‘great’ as we see it today. The Ming government expanded and enhanced the wall as a response to the Yuan takeover.)

The Chinese government was dominated by the Han ethnicity and had long considered Mongols to the north a threat. There were successful small invasions from time to time but in the late 1200s CE, Kublai Khan (grandson of Genghis Khan) accomplished what previous Mongol leaders had not: full takeover of China. The Mongols waged a protracted invasion against the then-ruling Song Dynasty but that was not all the Song leaders were dealing with. Ethnically Jurchen armies from Manchuria were invading as well. In fact, Jurchen advancement required that the Song move their capital from northern China (at Bianjing/Kaifeng, close to the border with Mongol lands) to the south (Lin’an/Hangzhou). According to the traditions of Chinese history (written by ethnically Han historians), the Song Dynasty was a prosperous period of native Chinese (Han) rule that ended in conquest.

As you might expect, people who had become used to Song leadership in China weren’t too happy that they had new leaders. The Yuan Dynasty was not well-loved by a particular group of scholar-officials now known as the Song Loyalists. When the Yuan took power, the Song Loyalists were the dissenters. You might imagine that they couldn’t really speak their minds out in public. But, these scholar-officials did have some weapons in their intellectual arsenal: the skillful use of imagery and metaphor to publicize messages to one’s peers. Many of these men were literati poets and painters.

One scholar, Ren Renfa, used his skill to depict the choice that officials had to make when the Yuan Mongols took over. Do I pledge my loyalty to this new government and remain a ‘fat horse’? Or do I maintain my loyalty to the conquered Song and become a ‘thin horse?’ Ren’s painting A Fat and Thin Horse (Fig. 14.5) illustrates this dilemma. ![]() The so-called fat horse is standing proudly, perhaps even prancing, with a gleaming speckled coat, well-maintained mane, and well-fed body. By contrast, the so-called thin horse bows its head. Its mane is missing or unkempt. The thin horse is beyond thin to the point of emaciation from lack of food. Its tail is curled beneath its hind legs like a scared dog.

The so-called fat horse is standing proudly, perhaps even prancing, with a gleaming speckled coat, well-maintained mane, and well-fed body. By contrast, the so-called thin horse bows its head. Its mane is missing or unkempt. The thin horse is beyond thin to the point of emaciation from lack of food. Its tail is curled beneath its hind legs like a scared dog.

You may have already noticed another strong distinction between the way Ren Renfa depicts these horses. They are both bridled with typical horse headgear, but the fat horse’s rein flows freely onto the ground while the thin horse’s rein encircles its neck. Have you surmised the visual metaphor? A thin horse is not just starving and depressed but controlled by others. Ren offers this contrast to reflect the mental, and even physical, states of those who pledge loyalty to the Yuan (fat horse) or remain Song Loyalists (thin horse). There were officials who made the thin horse choice, such as another famous painter of this time Gong Kai (check out his related painting Emaciated Horse). Stories of Gong’s life during the Yuan period include homelessness, begging, and other losses.

Song loyalists like Gong Kai were defying social norms and newly created power structures. Ren Renfa saw the choices before him and probably chose to be a fat horse. While the symbolism of horses is particular to China, you probably can think of ways that government officials in a country where you have lived have represented themselves as either loyal or not to the ruling group at any given time. In Yuan China, that was primarily done through art. Check out The World of Khubilai Khan (Watt and Hearn 2010) to learn more about arts during the Yuan Dynasty and the dynasty’s founder.

Political defiance, today

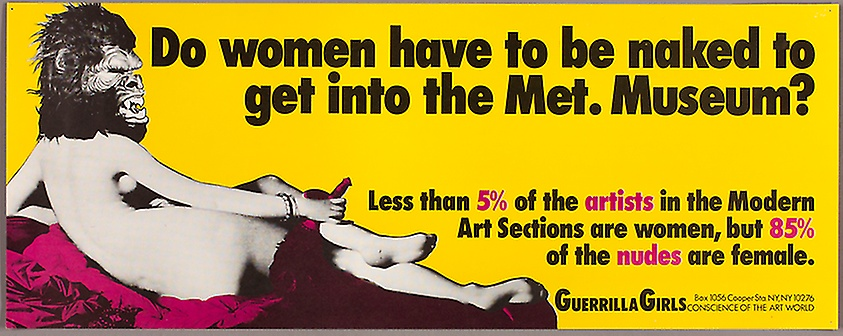

In more recent years, political dissent has related strongly to underrepresented identities and those without the privileges of power. Women artists of the 1980s CE challenged the art world and the Western Canon by bringing the political approach of feminism into their radical artworks. The most famous group associated with this movement is the Guerrilla Girls, a collective of anonymous artists in New York City starting in 1985 and continuing today. Their group name refers to guerrilla warfare wherein tactics beyond formal military norms are used to win in conflict situations. The Guerrilla Girls also dubbed themselves “the conscience of the art world” (Fig. 14.6).

The Guerrilla Girls used unconventional methods to broadcast a political message to the art world. Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum? is a large-scale poster originally created for the advertising spaces on New York City buses. The Guerrilla Girls undertook a visual campaign to challenge museums, particularly calling out the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Along with the primary title, the Guerrilla Girls incorporated clear evidence of bias for men artists in the Met’s modern art collection.

Like Hank Willis Thomas, the Guerrilla Girls appropriated imagery to build this work. In this case, they appropriated a portion of famous French painter Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres’ Grande Odalisque from 1814 CE. You may recognize Ingres’ painting even if you have never studied Western art because it is that famous, as a part of the Western art tradition of lounging nude women in luxurious surroundings (this is also an example of Orientalist painting as discussed in “Where Do Babies Come From?”).

Looking back at Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?, you’ll notice that the Guerrilla Girls have only used the Odalisque’s body and the feather fan she holds. They have replaced her head with a gorilla baring its teeth, as if the Odalisque is wearing a gorilla mask. The image presents an objectified woman’s body as if she is part of the Guerrilla Girls, putting on an anonymous identity and joining the cause. Just as they intended, the Guerrilla Girls shook up the New York City art scene in the 1980s CE and greatly contributed to the continuing dialogues that challenge the institutions of the art world, including museums (more on that in “Why Do People Take What Doesn’t Belong to Them?”). UTA Student Andrea Macias used the Guerrilla Girls as a comparative example in an essay, entitled “The people without faces and their fight against the unjust,” focused on a work by Mexican photographer, Issac Guzman.

In this discussion of political defiance in art, you may be thinking that we’ve neglected someone. Indeed, we cannot have this conversation without discussing Ai Weiwei, a contemporary artist from China. He is a very prominent artist and public figure today, coming to public acclaim by producing huge installations in high-profile museums such as the Tate Modern in London. You have probably encountered his work often called “Sunflower Seeds,” originally exhibited at the Tate in 2010 CE and titled 1-125,000,000.

The original title is important context to understanding this work. Ai commissioned local artists of Jingdezhen, the porcelain capital of historic China, to mold, fire, and paint millions of life-sized sunflower seeds. The exhibition consisted of a several inches thick layer of these individually created seeds across a vast floor. Ai created this mass of seeds as a reflection upon the imagery of early communist China wherein founder Mao Zedong was presented as the sun with sunflowers open before him, with seeds pointed in his direction (Fig. 14.7). During the ‘Cultural Revolution’ of China, children would sing a song praising Mao, “Red Sun, Chairman Mao, Every Sunflower faces you.” This was a common visual metaphor of the time, with the seeds of these sunflowers representing the Chinese people. They respond to Mao, like sunflowers open up to the sun every day. This popular idea may derive from the fact that sunflower seeds have been a common snack for many Chinese people for a long time. Redefining Propaganda in Modern China (Johnson 2020) offers tons of detail about Mao-era political imagery.

The interpretations of the meaning of Sunflower Seeds / 1-125,000,000 vary. Some commentators focus on Ai’s creation of a massive amount of small objects like the mass production of commercial products in China today, but ironically every one of the millions of seeds was handpainted. Many people see this as a challenge to the common, often derogatory, assumptions about the cheapness of goods ‘Made in China.’ At another level, scholars consider Ai’s presentation as a visual representation of the dichotomy between the individual and society. Presented as a vast sea of seeds, viewers might focus on the high quantity and the implications about the large population of China since seeds represent Chinese people in Maoist imagery.

But, take another look at the poster with Mao and the sunflowers. Do you get the feeling that those seeds are represented for their individuality and uniqueness? Probably not. The poster shows the seeds as cohesive, contained, and reverent, not as individuals but as a whole. Ai often talks about the tension between the individual and society. Which is more important? Communist nations say society. Democratic nations say the individual. Do you lose one if you prioritize the other? Ai doesn’t have answers to these questions. He is posing the questions so that you can consider how you would answer them and how governments around the world address them.

Ai has not abandoned the sunflower image in more recent years. In 2020 CE, he created a limited print run of surgical masks as a philanthropic project at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Printed Mask (Fig. 14.8) was purchased from Ai’s online platform with proceeds donated to humanitarian relief. Recognize the imagery? Sunflower seeds! Ai printed several other designs on surgical masks in this series, including his famous middle finger and feishu, a Chinese mythological creature.

There are many ways to interpret Ai’s project and the choice of sunflower seed imagery on masks used to combat the COVID-19 pandemic. If we follow the interpretation that the seeds represent people in society (and the question of individuality versus the whole), the implication of ‘social distancing’ efforts during the pandemic reflects a meaning that many commentators brought to the media during the pandemic. Self-imposed and/or government-mandated isolation of individuals impacts society. Yes, it was a measure to slow the spread of the disease but it also resulted in significant loss of social connection. It resulted in social losses to ensure individual survival. Again, Ai does not provide answers but asks us to think about the questions.

Decolonialism, Postcolonialism and Defying Loss

Review the discussion of decolonialism and postcolonialism in “Where Does Art Come From? An Introduction.” Don’t those movements sound a lot like political and social defiance? Art often plays a large role in decolonial and postcolonial movements. Think back to the Song Loyalists and the use of imagery and metaphor to speak their mind. They used artistry to present an unfavorable opinion. In colonial settings, opinions in defiance of colonialism are often not tolerated and/or result in violence. Such art can hide its ‘true feelings’ through metaphor and symbolism. Postcolonial art often has a literal or straightforward character because some of the pressure of colonial norms lifts through independence. Furthermore, postcolonial arts often respond to losses of cultural heritage and knowledge.

Some cultures see the preservation of cultural heritage as an important postcolonial mission. Located in an island archipelago in central Polynesia, the people of Tonga hold traditions very dear. Importantly, the Kingdom of Tonga is the only surviving indigenous monarchy (wherein the kings and queens today descend from an unbroken line of indigenous leadership) in the Pacific. While the Kingdom of Tonga borrowed significantly from the British, their tradition of leadership is indigenous and linked to the lineage of Tongan rulers since the earliest chiefs. It is also important to note that Tonga was colonized by the British but Tongan kings retained their power (unlike other colonized groups). In this distinct way, Tongan culture was impacted by colonization and their arts today take on a postcolonial attitude about cultural heritage and preservation.

Above all other arts, Tongan peoples honor the traditions of barkcloth production and use (similar yet distinct to the Pongo barkcloth traditions of the Mbuti discussed in “What is Important to Us?”). Barkcloth is the most important koloa (valuable and prestigious item) in Tongan society and its production is gendered: only women create barkcloth and undertake its decoration. Scholar Adrienne L. Kaeppler (1990, 63) learned through her anthropological fieldwork in Tonga that koloa are not just beautiful objects, but they have agency that actually regenerates Tongan culture. This cultural power of barkcloth derives from its makers: Tongan women.

Barkcloth (Fig. 14.9) represents a high quality example of such artworks that would be used in ritual presentations, weddings, funerals, as well as for clothing and bed coverings. As demonstrated in Figure 14.9, Tongan barkcloth is stored in rolls. This relates to one of the ways to view barkcloth, especially at ritual presentations. Kaeppler (1990, 66) experienced many examples of the unrolling of barkcloth which is seen by Tongans as a process of unveiling and revealing. These unraveling events would be accompanied by lyrical storytelling and dancing providing the narrative context to the barkcloth. Barkcloths often relate to the particular histories of villages or the great deeds of a chief. These communal events wherein barkcloth and related narratives are the stars of the show provide evidence to Kaeppler’s understanding that barkcloth and the women who produce it are honored as the perpetrators of Tongan culture. Barkcloth is the roadmap of the stories Tongans tell and the women who make them are the ultimate storytellers.

Another important facet of postcolonial arts is identity seeking in the wake of independence. This is particularly true of the postcolonial movement of India. As already mentioned, India gained independence from the British Empire, alongside partitioned countries Pakistan and Bangladesh, in 1947. Imagine that you are a citizen of a country that for hundreds of years has been part of a colonial system. Suddenly, your country is independent and must make its own name on the world’s stage. This is not easy. Many countries continue to face very rocky roads in postcolonial periods economically, politically, and socially. In social movements, artists and scholars start posing questions you are familiar with already: Who am I? What are we about?

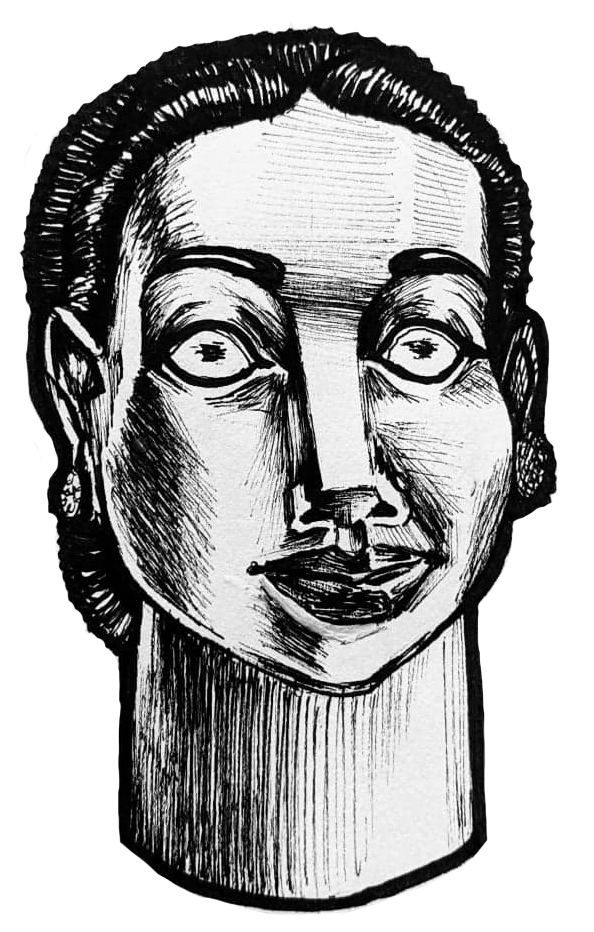

One famous contemporary artist from India offers monumental statements addressing such postcolonial concerns, in artworks such as Devi (sketched in Fig. 14.10; original here). Ravinder Reddy creates massive fiberglass heads representing women of Hindu India. These women are adorned with beautiful polychrome hairstyles made of flowers. Their yellow/gold skin tones and staring eyes are particularly striking to the viewer. Remember Bichitr’s self-portrait in Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Sheikh to Kings (Fig. 14.3)? His yellow robes signify that he belonged to the Hindu tradition (unlike Jahangir who is Muslim). The bright gold and yellow tones in Reddy’s work reflect the prominence of Hinduism in India and reinforce the allusion he makes to representation of women protecting many Hindu temples today.

Each set of monumental eyes given to these women demonstrate assertiveness and even confrontation. The attitude of these sculptures is Reddy’s response to the postcolonial questions of Indian identity. Reddy looks to the women of his daily life. They are his picture of India and where the future of India, as a continuing growing independent nation, lies.

Many critics and scholars have noted that Reddy’s monumental heads sit at a crossroads between pop art and folk art, between global pop culture and age-old Hindu traditions of India. As evidence of this, the first exhibition where his monumental heads made an appearance was titled “Contemporary Art in Asia: Traditions/Tensions.” Striving to maintain traditions but feeling the tensions of contemporary globalization are hallmarks of postcolonial arts that work to defy the norms of colonial power.

The Wrap-up

We all have our traditions and tensions that sometimes conflict with each other. We all wage battle against forces we want to repel at some point in our lives. Many artists throughout time and across the world have taken these tensions, struggles, and battles against the powers that be as the central focus of their work. They become a voice in large social and political struggles. Their voices can sometimes define a movement. Continue exploring the artists discussed in this chapter and other examples of defiance in art by checking out the media recommendations and scholarly sources below.

News Flash

- Hank Willis Thomas is active on Instagram @hankwillisthomas. He also contributes to the @forfreedoms project on Instagram.

- Do you like the Guerrilla Girls’ attitude? Check out their official website at guerrillagirls.com.

- Check out Ai Weiwei’s documentaries including “Disturbing the Peace” (2009), “Hua Hao Yue Yuan” (2010), “So Sorry” (2011), and “Coronation” (2020).

- Curious about how you would make Polynesian barkcloth? There are process videos on YouTube demonstrating “Harvesting the Mulberry,” “Processing the Mulberry,” “Dying the Cloth,” and “Making Dyes and Painting the Cloth.”