7 Will You Tell a Story?

Will you tell a story?

What do bedtime, Snapchat, and To Kill a Mockingbird have in common? Stories! Some are comforting. Some are provocative. Many are very personal. In this chapter, we discuss how storytelling and narrative go hand-in-hand with visual arts. Indeed, visual arts are often the most important vehicles for stories because they last longer than generations. As people die, stories may die with them if they are not told to the next generation, written down, or visualized in a permanent medium. The most important stories, and those that are often immortalized in stone, clay, or paint, often relate to how cultures developed, either realistically or mythologically.

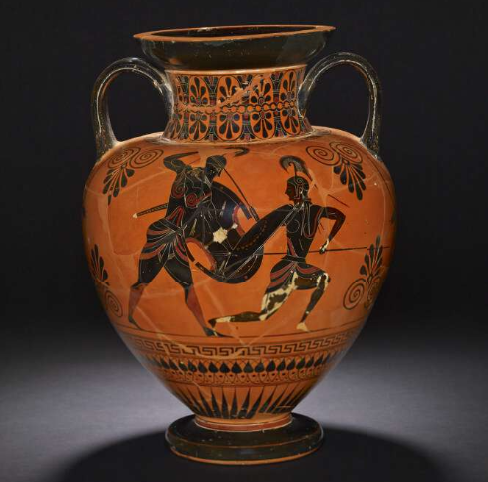

Most people educated in European or Euro-American schools are familiar with Greek mythology. Ever heard of Achilles? The term ‘my Achilles heel’ and the biological name of our Achilles tendon derive from the Greek myths about this heroic figure’s exploits during the Trojan War, classic of the Western Canon of literature. A lesser known myth about Achilles inspired the decoration on Black-Figure Amphora (Fig. 7.2). Achilles (left) plunges a spear towards Penthesilea (right), a Queen of the Amazons. Penthesilea deflects the blow with her shield. You can see the gendered differences between the two characters: Achilles’ bearded face and Penthesilea’s long hair and breasts.

The Amazons were described in many Greek myths as a society of women warriors and hunters with the prowess and skill to defeat men (with no relation to the Amazon River in South America except when a conquistador was reminded about the Greek myth through interactions with an indigenous group and gave the river its modern name). While the origins of the Amazons were not clearly described by Greek writers, recent archaeological evidence suggests that the stories featuring Amazons were, at least in part, based on real women warriors of Scythia, Sarmatia, and ancient Siberia, all cultures of Central Asia, within the Eurasian Steppe region (Fig. 7.1).

These cultures are relatively unknown to European and Euro-American audiences, even though they may feature in one of the foundations of Western culture (classical mythology). In addition, scholars have shown that these cultures form part of the ancestry of modern Slavic peoples who now live across Eastern Europe. Art of the Eurasian Steppe, found primarily in burials in southern Russia and Ukraine, is not considered part of the Western tradition until Greeks colonized portions of their lands around 300 BCE (thanks to Alexander the Great).

One of the most remarkable burials from this region was frozen in time, literally. Before Greeks arrived, around 500 BCE, Princess of Ukok of the Pazyryk culture (located east of Scythian lands) was regally buried and then (probably unintentionally) mummified via freezing. The frozen conditions not only preserved her body but most of the burial objects, including those of perishable materials that almost never survive. Skin is also perishable but mummification (by a variety of means) can preserve it, along with any body modifications such as tattoos.

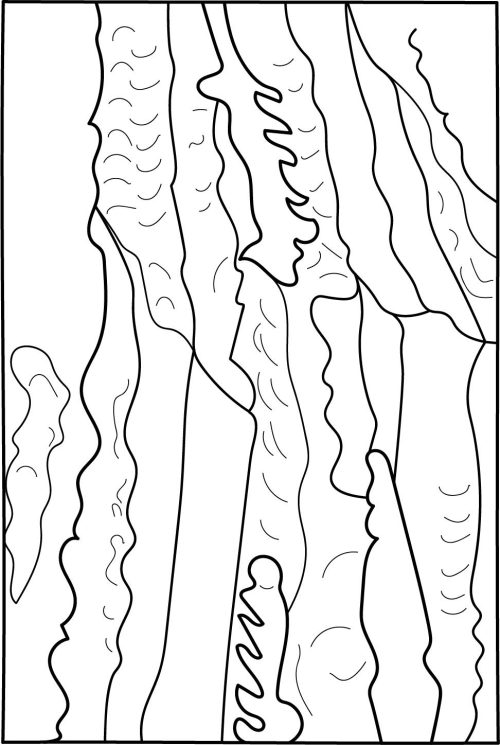

Princess of Ukok is not the only one! There are at least 6 mummified bodies from the region that retain tattoos. Each of the mummies retains at least one tattoo (most have multiple and up to 12) reflecting the Pazyryk ‘animal-style’ of art. View photographs and drawings of these tattoos in “Tattoos from Mummies of the Pazyryk Culture” (Iwe 2013, Figs. 2-16). Did you notice all those horns?

Deer are frequently depicted in these tattoos, probably because they were sacred animals to Pazyryk peoples. Birds of prey, snow leopards, sheep, and horses are represented as well. Iwe’s (2013, 93) study of these zoomorphic tattoos demonstrates a distinction between depictions of real animals and “fantasy,” hybrid creatures. Hybrid forms may incorporate special attributes associated with the Pazyryk spiritual system. Thus, these tattoos, such as Horned Creature Shoulder Tattoo (sketched in Fig. 7.3; original here) may represent Pazyryk deities. Work is still ongoing to understand the significance of this tattoo imagery. Iwe (ibid) suggests that “tattoos show a special code […] based possibly on the foundation myths of the Pazyryk society.” If representative of myths, these tattoos demonstrate that stories probably mattered just as much to the Pazyryk peoples as they did to the Classical Greeks. UTA student Nicholas found these tattoos inspiring and created a video project entitled “An Artistic Analysis of Hyper Light Drifter’s Setting and Narrative,” exploring how class themes are relevant to one of his favorite video games.

Starting at the beginning

Pazyryk ‘foundation myths’ are their creation or origin stories. Some of the most important stories told in a society relate to creation and/or the beginning of the world. What anthropologists call creation narratives or mythologies are not fantasies or works of fiction in people’s minds. These are recollections of the earliest parts of their histories.

Ancient and historic Maya peoples of eastern Mesoamerica circulated several creation narratives. Most early narratives reflected the worship of the Maize God (their version of the Maize God, not the Olmec version from “What is Divine?”). The Maize God Mural Reconstruction Painting (Fig. 7.4) recreates a mural painting by Maya artists living during the Preclassic period in modern-day northeast Guatemala (Fig. 7.1). The original murals are difficult to view in photographs due to deterioration. The Maize God Mural is part of a series that spanned the upper portions of interior walls in a single-room structure, known as Las Pinturas, built around 100 BCE. Las Pinturas was built towards the end of the Preclassic period, known as the Late Preclassic (300 BCE – 250 CE).

There are two primary components of the Maize God Mural composition, read from right to left. The longer portion on the right is framed by the long horizontal feature at the bottom. What do you think that is? Look carefully at the feature as it turns up at the far right and transforms into a … head of a serpent-like creature with its jaws open, spewing curling red spirals! If you follow the red, yellow, and white body of the serpent to the left, notice the black footprints, presumably left by the characters that walk on the body of the serpent above. As your eyes reach the end of the serpent’s body, it appears to emerge from an overhang of some kind, within which a woman kneels. Just above her head, curving shapes mingle with iguanas, snakes, trees, and even a spotted jaguar. If you look just above and to the left of the kneeling woman’s head, do you notice a curious feature hanging from the overhang? What does that resemble? Have you ever been spelunking?

That’s a representation of a stalactite, the stone formations of cave ceilings. The woman kneels inside the mouth of the cave! This isn’t just any cave… it has fangs. Like the jaguar above it, the Maya believed that special cave openings, sometimes termed mouths of caves, were considered to be the open maws of cosmic earth monsters. They were the divine embodiment of the earth and generally were associated with the origins of rivers, streams, and springs. The serpent creature that emerges from the mouth of the cave, represents the water source (because when you see a snake in the forest, that’s a good sign you are near water). This scene takes place in front of the mouth of a cave, from which life-giving waters flow. FYI: While the Tairona, discussed in “What is Divine?” and the Maya are distinct cultures, they probably shared the view of caves as important places on the landscape because they are often sources of water. The Tairona specifically focused on cave-dwelling bats while the Maya anthropomorphized cave openings.

Back to the Maize God Mural. The kneeling woman faces a procession of figures. Who is the most important figure, do you think? Scholars think it is the fifth figure from the right, standing with hands outstretched and represented with a fully red body. The red-bodied figure looks at two kneeling figures behind him (his head faces a different direction than his body), and three trailing figures, one with an impressive headdress, and two carrying heavy bundles. The red-bodied figure’s hands touch a squash, or calabash, from which viney tendrils and flowers sprout. Most scholars think the red-bodied figure is the Maya Maize God, similar but distinct to the Olmec Maize God.

Turn your attention to the scene to the left of the cave mouth. There is an elaborate standing figure, holding a special implement. To the left of that figure, is a … calabash! It is decorated with the same diagonal yellow band and motifs as the calabash the Maize God touches in the scene on the right. But this calabash is not sprouting flowers, it is cut open at the top and sprouting… a human! In fact, before the human emerged, the four red baby-looking figures with curly umbilical cords, arranged above and below the calabash, emerged! Many scholars have suggested (though there is some debate) that the standing figure is Chaak, the Maya rain and storm god. In Maya mythology, Chaak wields an axe that cracks like thunder and produces lightning when it strikes the earth. In this scene, it appears that Chaak’s axe struck the calabash (a stand-in for the earth, or a seed within the earth), tore it open, and allowed the entities to emerge. Thus, rain produces life.

Who are those babies? There have been several interpretations, including that they are linked to infantile imagery among the Olmec, but if that is the case, it’s probably a general versus specific link. One distinct interpretation suggests that the four babies represent the four directions of the earth, the land that stretches around us, and that their umbilical cords are connections to the sky realm. Thus, they metaphorically represent the land, or the physical surface of the earth. Once the land is formed, what emerges? The first human, perhaps the first king! Have you gleaned the overall purpose here? This is a visualization of the origins of humanity, a creation narrative. At the mouth of a sacred cave, the Maize God provided the fruit/seed that was nourished by the rain god Chaak to produce the land and the people.

Importantly, this is just one creation narrative among many that probably existed during the Maya Preclassic Period. This was the one considered important by the elites of the site we now call San Bartolo (they didn’t call it that). But there were Maya living in many different areas during the Preclassic Period, far afield from San Bartolo, such as those living in the mountainous highlands of southern Guatemala. Different regions often have different creation narratives that reflect different landscapes and histories.

Also importantly, creation narratives change! For example, Maya people living during the Postclassic period favored the mythology found in the Popul Vuh, a book translated by Tedlock (1996) in Popul Vuh: The Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life, Revised Edition. The Popul Vuh focuses on the sons of the Maize God, known as the Hero Twins, Hunahpu and Xbalanque. They defeat the Lords of Xibalba (the Underworld) by playing the ballgame and bring about the resurrection of their father. The Hero Twins eventually ascend into the heavens to become the sun and the moon. For many years, most scholars thought that this version of the Maya creation story was developed very late in Maya history. However, archaeologist Richard Hansen recently discovered a series of exterior plaster murals on buildings at the site known as El Mirador in Guatemala (not too far from San Bartolo), which may reflect the story of the Hero Twins, as early as 300 BCE. This evidence suggests that several different creation narratives, with similar themes and characters, were probably circulating across the Maya world at any given time.

What happened between the Preclassic Period and the Postclassic Period, you ask? The Classic period (ca. 250-900 CE), of course! (Review how these terms reflect bias in scholarship in “Where Does Art Come From?: An Introduction.”) Vessel of Dancing Lords (Fig. 7.5) is an excellent example of Classic period Maya painted pottery. This vessel is especially significant because it is signed by the artist! The hieroglyphic inscription near the rim identifies Ah Maxam as the maker and the style indicates that the artist worked in or near to the Maya city known as Naranjo, Guatemala (Fig. 7.1).

Following from the Preclassic San Bartolo Maize God Mural and the El Mirador murals, the imagery on this vessel relates to the creation narrative emphasized in this region during the Late Classic period (ca. 600-900 CE). In this case, leaders costumed as the Maize God, perform/reenact creation and the cyclical rhythm of life and death. The hieroglyphic inscriptions and other context clues help scholars make the distinction that this is a person performing as the Maize God, versus the ambiguity discussed with the Tairona Gold Figure Pendant (Fig. 4.3) in “What is Divine?” Figure 7.5 focuses on one of the three repeating panels on the vessel, each featuring a Maya lord dancing energetically.

It may be difficult to make him out. Start at the feet: at the thin ground line, locate a flatly planted left foot and right foot resting on toes with heel raised. Then follow the line of the right leg up to bended knee, over an ornate belt, across the torso leaning to the left, with an arm extended towards a court dwarf on the far left. Then, find the lord’s face looking left in profile. Something confuses and overwhelms our eyes as we try to make out the dancing figure. It is the enormous and elaborate back rack and headdress he wears (primarily depicted to the right of his body). Back racks (like backpacks made of wood) were sturdy embellished components of costumes worn on the back that allowed attached feathers, textiles, and other painted items to tower over and behind the dancer. (P.S. The Singing priest in Mural Fragment with Elite Male and Maguey Cactus Leaves [Fig. 6.8; “What is Important to Us?”] also wears a back rack.) In addition, the lord’s headdress features extravagant feathers and sacred items probably made of jade and obsidian. At the far right of Figure 7.5, where there has been loss to the ceramic body of the vessel, you will see that there is another court dwarf standing. The scene repeats. Everything between the dancing body and the right-most dwarf is the back rack that the lord sports to adequately represent the significance of the figure he personifies: the Maize God.

The Vessel of Dancing Lords demonstrates how significant creation narratives and the primary deities that feature in them were in Maya life. In the wet and humid climate of Mesoamerica, rulers themselves dressed in heavy and cumbersome costumes to bring the Maize God to life. What a workout! They would perform in plazas and/or on staircases surrounded by monumental structures that supported the temples and palaces of the city. These rulers showcased their special relationship with the divine and the origins of Maya society, reenacting creation narratives very similar to that represented in the Maize God Mural. Their ability to perform, and take on the persona and power of the Maize God, was a marker of their ability to rule. Learn more in “Plazas, Performers, and Spectators: Political Theaters of the Classic Maya” (Inomata 2006).

Experiencing creation

Different people consider the origins of humanity differently. The Maize God was significant to the creation narratives of many Mesoamerican cultures. If we take a trip northwest of Mesoamerica, to the Chihuahuan Desert of northern Mexico and the Southwest US (Fig. 7.1), we encounter a distinct creation narrative, which still resonates with people today.

The White Shaman Mural (Fig. 7.6) is one of the most famous examples of Pecos River rock art. The Pecos River runs north to south, generally parallel and eventually merging with the Rio Grande, across New Mexico, West Texas, and northern Mexico. Archaeologists who study ancient rock art flock to the confluence of the Pecos and Rio Grande Rivers. This region, around the Seminole Canyon State Park in Texas, exhibits one of the highest densities of rock art in the US. Ancient people in this region, generally called Pecos River Peoples, painted important imagery in caves and rock shelters that were probably sites of ceremony, residence, or both.

When first studied, archaeologists viewed the White Shaman Mural as a palimpsest, a layered artwork that many artists contributed to over time. If true, the mural would be a random collection of paintings done by many different artists with different intentions. Despite this, archaeologists recognized that there were abstract human figures present in the mural and one of them, represented with a white body, stood out from the rest. This ‘white shaman’ became the poster child for the mural and thus, the mural got its name.

We know better now. Archaeologist Dr. Carolyn Boyd came to the study of the White Shaman Mural as an accomplished painter with an eye for composition. When she viewed the mural, she did not see a random assortment of unrelated images (as in the palimpsest theory) but a coherent and planned narrative composition, within which the famous white shaman was a secondary character. So what’s the story?

To figure that out, Dr. Boyd had to think outside the box. She studied the living cultures of Yaqui (Hiaki) and Huichol (Wixáritari) peoples, native the Chihuahuan Desert. These groups were still practicing shamanism, the spiritual tradition that dominated the region prior to Spanish conquest. Many archaeologists interested in the ancient cultures of the Southwest US and northern Mexico view the Yaqui, Huichol, and others as important sources of ‘ethnographic analogy,’ a technique to develop interpretations about the past based on evidence from the present. Studying contemporary and/or historically documented groups can lead to insights about how past people lived or what they believed, if there is evidence of cultural continuity (which can be a matter of debate). Yaqui and Huichol shamanism are considered to be good analogies for practices of ancient peoples of the Chihuahuan Desert. In particular, Dr. Boyd realized that the description of peyote hallucinogenic experiences among the Yaqui and the significance of the divine deer within Huichol mythology could help interpret the White Shaman Mural.

Heard of peyote? It is a button-shaped cactus native to the Chihuahuan Desert, that produces psychoactive substances and when ingested can induce hallucinogenic experiences. Dr. Boyd learned that when Yaqui shamans ingest peyote and feel the psychedelic effects, they often remark that it feels like “being swallowed and passed through the body of a snake” (Boyd 2003, 54 citing Beals 1943: 64). Distinct to Tairona transformation experiences discussed in “What is Divine?”, this Yaqui experience would transport the shaman into the ‘otherworld’ – the realm beyond this one where one can seek healing, communicate with the divine, and understand the origin of things (ibid). Shamans have a ‘spirit guide’ that helps them navigate the otherworld (ibid). Huichol shamans follow the divine deer as a sort of ultimate spirit guide who traces the lineage of humanity from the first people to those living today.

Do you see reflections of these elements of contemporary indigenous cultures in the ancient White Shaman Mural? Review this reconstruction drawing of the mural for more clarity. Look closely near the bottom of the mural. You’ll notice a white undulating line running from left to right. What does that make you think of? That is the body of the snake! Now look above and below that line. Do you see the regularly spaced repeating figures, five in total, with long torsos, thin legs, outstretched arms, white faces, and red heads? These are the main characters of this narrative and the compositional component that made Dr. Boyd realize this wasn’t just random disjointed paintings but a planned depiction of traversing from our realm to the otherworld.

Originally painted with black pigmented bodies that have faded to a bluish gray over time, the five figures are shamans ingesting peyote (all the little black dots on the right and at the center) and traveling with their spirit guides (the figures, including the white shaman, depicted next to or above each black shaman). Their travels through the body of the snake lead them to the otherworld, mostly depicted beneath the white undulating line. At the far bottom right, notice the red and black feature that appears to be notched. Just to the left of this notched feature, do you recognize that animal? It is a red deer. This combination of elements really got Dr. Boyd’s attention. The Huichol creation narrative centers upon the divine deer who guides the first humans from the watery underworld (associated with the colors red and black) to the ultimate settlement of humanity at ‘Dawn Mountain.’ The brown notched archway on the bottom left is Dawn Mountain, where according to Huichol tradition, the divine deer sacrificed himself (note the deer with an arrow in its neck above the archway) and the sun rose for the first time (the first dawn). The deer’s sacrifice is a means for the first humans to learn to hunt and their first meal. Above Dawn Mountain, the peyote-deer deity (an antlered human) rises from the underworld.

It is important to note that Dr. Boyd does not apply this ethnographic analogy to suggest that the White Shaman Mural was painted by Yaqui or Huichol people. Dr. Boyd’s team accurately dated the mural to approximately 2000 BCE, applying scientific dating techniques to carbon-based pigments. Instead, the connections between the contemporary Yaqui and Huichol to this ancient painting help us to learn that there are long-established and continuing mythological and ritual traditions in this region. Dr. Boyd argues that the painters of Pecos River rock art were the ancestors of the Yaqui, Huichol, and other peoples. Her book The White Shaman Mural: An Enduring Creation Narrative in the Rock Art of the Lower Pecos (Boyd 2016) changed the game in rock art studies of the region, demonstrating that narrative sophistication and heritage are much older than previous scholars thought.

To the north of the Chihuahuan Desert in the Four Corners region of the US, sacred architecture offered a means to re-experience creation in a different way and according to different mythologies. In the Southwest US (New Mexico, Arizona, etc.; Fig. 7.1), you’ll find the modern-day reservations of Hopi, Diné (Navajo), and related cultures. As discussed in “Who Am I?” the Diné are more recent migrants to that region, whereas the Hopi are a Puebloan culture with deep roots. Puebloan (a term derived from Spanish) refers to cultures that live in permanent dwellings of adobe, often multi-storied with flat roofs. Modern Puebloan groups mostly live on reservations created by the US government based on unequal relationships and forced resettlement of indigenous peoples (see “How to Read this Book & Land Acknowledgement”).

The predecessors of the Hopi and other Puebloan groups are known as the Ancestral Puebloans. In the past, this culture was called the Anasazi, a name from the Diné language that means ‘ancient enemy’ or ‘ancient outsiders.’ Since the Diné often were in conflict with Puebloan groups like the Hopi, they applied an antagonistic term to Puebloan ancestors. Modern Puebloan peoples view the term Anasazi as disrespectful. They promote the use of (and changing of textbooks to reflect) the term Ancestral Puebloan.

The Ancestral Puebloans were the builders of cities like Chaco Canyon (New Mexico), Mesa Verde (Colorado), and Taos Pueblo (New Mexico). As their name and descendants demonstrate, they are known for building pueblos of multi-family houses of adobe bricks. Check out the ancient apartment complex called Pueblo Bonito at Chaco Canyon. In addition to their residential structures, the Ancestral Puebloans built unique ceremonial structures called kivas (Fig. 7.7). These are semi-subterranean (partly below and above the ground surface) and circular. Interior kiva spaces are accessed using a ladder from a hole in the ceiling (see the reconstructed kiva at Spruce Tree House at Mesa Verde, Colorado) or steps integrated into the upper portion of the circular wall.

Imagine the Kiva of Casa Rinconada (Fig. 7.7) reconstructed like the Mesa Verde example. These are dark, enclosed spaces with only one or two sources of light. In fact, the interior could be concealed from all sunlight if needed, only illuminated by the central fire hearth, ventilated through the ceiling. Imagine the heat and the scent of the fire!

Most kivas have an interior bench and niches integrated into the circular wall. Benches were for the people viewing and participating in the ceremonies and the niches likely served as storage for ceremonial objects and/or a metaphorical function discussed below. The Casa Rinconada kiva served a whole community, and therefore large groups of people at one time, whereas smaller kivas like the one from Mesa Verde within which smaller groups of people would gather, sometimes a single family or lineage. Large residential complexes like Pueblo Bonito contained numerous kivas, likely used by distinct groups and/or dedicated to distinct rituals.

Who descended the ladder or steps and sat on these benches? The answer is everyone, but mostly men. In Ancestral Puebloan society, community members of all ages would gather for important occasions but the most frequent participants in kiva ceremonies were men. Scholars think that women may have congregated for their own set of rituals in so-called ‘mealing rooms,’ as part of their responsibilities for preparing corn into ground masa (corn meal; from which foods like tortillas and tamales are made).

What were the rituals associated with kivas? Scholarly understanding of these rituals is limited to what descendants of the Ancestral Puebloans, such as the Hopi, chose to share. These ceremonies involved some of the most sacred and special aspects of Puebloan culture. It is understandable that some things will be kept secret and held as internal knowledge. From what we do know, the kiva is not just a place for these special rituals but a microcosm of the Puebloan universe, and a visualization of their origins.

The subterranean feature of kivas is not happenstance; it is profoundly meaningful. As one descended into the kiva, they travelled in time to the origins of their society. Puebloan mythology tells us that the first people emerged from a hole in the ground, like the corn and other plants that were so integral to their livelihood. These first people, like seeds, came from a place of darkness, up into the light, and learned how to sustain themselves in harmony with the land. Kivas usually have a central hole in the ground called a sipapu. This is the ‘place of emergence’ according to present-day Puebloan people. The niches may relate to the sipapu as holes from which life emerges from dark to light. Every descent into the kiva was a way of remembering one’s origins, remembering the stories of one’s ancestors, and continually renewing one’s relationship with the past.

Let’s consider one more example of origins and storytelling by traveling from New Mexico across the Pacific to Alhalkere, Australia (Fig. 7.1). A famous Aboriginal artist, Emily Kame Kngwarreye, descended from the indigenous peoples of arid central Australia. Kngwarreye invested in her cultural heritage, including sacred rituals, dances, songs, and body painting traditions, becoming a ceremonial leader of Awelye (women’s business). Kngwarreye spent much of her time in the desert, as a camel handler and stockhand moving herds between watering holes. She mentally mapped the desert landscape of Alhalkere over these years. That became the subject of her art.

Unlike some of the exoticized stories told about her, Kngwarreye was not an isolated indigenous woman naively painting in the desert. Emily learned various art techniques through adult education classes offered by organizations such as the Central Australia Aboriginal Media Association, which exposed the work of indigenous peoples to mainstream Australian society. In her 60s, Kngwarreye learned many styles of art, including imported batik making and Western painting on canvas. To learn about Aboriginal Batik (somewhat related to the batik discussed in “Who Am I?”), check out the exhibition “Across the Desert: Aboriginal Batik from Central Australia (National Gallery of Victoria 2008 – 2009). Kngwarreye made batik fabric paintings in the 1980s and early 1990s CE. Then, in the mid-1990s CE, Kngwarreye began experimenting with applying acrylic paint to canvas with household implements, such as shaving brushes, producing works like Yam Story I (sketched in Fig. 7.8, original here).

The title Yam Story relates to the embeddedness of storytelling within Aboriginal societies. In English, we can only approximate the nature of Aboriginal storytelling and thought, much of which concerns the time of creation before humans existed, known in English as ‘The Dreaming’ or ‘Dreamtime.’ Dreamtime stories were only ever passed on orally, through spoken word, songs, and dances. Stories of the desert landscape, teaming with the memories and continued presence of ancestors, often incorporate the wild yam. This resilient tuber is a source of life in the arid desert. As a leader of Awelye, Kngwarreye took on the responsibility of passing on the Dreamtime stories of yams and fertility of the desert to future generations of women. Her paintings reflect this important aspect of her ritual life and her practical knowledge of the desert.

Kngwarreye’s abstract style and experiments with Western derived media like acrylic paint contributed to the aura of her work within the art world. Very soon after her paintings like Yam Story I were shown in galleries in Australia, the global art market coveted them. Eventually, an entire museum was built dedicated to her work: The Emily Museum in Cheltenham, Australia. Art dealers and journalists wanted to hear from Kngwarreye herself to report on her fame and success. For example, in One sun one moon: Aboriginal art in Australia (Green 2007, 205), a quotation from Kngwarreye explains the reason behind her shift from batik textiles to painting, “… My eyesight deteriorated as I got older, and because of that I gave up on batik on silk – it was better for me to just paint.” At the end of her life, Kngwarreye became a household name in Australian art and was somewhat hounded by art dealers to purchase her work. Recently, one of her most famous paintings, Earth’s Creation, was sold for over $1.6 million. This sale demonstrates how much monetary value the art market places on Kngwarreye’s work but cannot compare to the value of her storytelling ability and contributions to her ancestral lands. UTA art student, Johnny Antram, was inspired by Kngwarreye’s visual and narrative brilliance for a word-focused laser cutting project in a digital media class.

Kingly and divine beginnings

Sometimes creation stories carry a flavor of royal heritage and lineage, if royal leadership played a significant role in the settlement and/or unification of a society. This is the case for the Kuba Kingdom primarily located in the southern regions of present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo (Fig. 7.1). The peoples that eventually established the Kuba Kingdom migrated to their present location as major changes were occurring across Africa due to European contact. The migrants settled around the Sankuru River, incorporating an existing society living there already, the Twa.

By the 17th century CE, one ethnic group called the Bushoong in this region came to dominant the rest and established the Kuba Kingdom, incorporating the local Twa as well as the Ngeende, Kel, Pyaand, Bulaang, and many others who probably migrated together. The leaders of the Kuba Kingdom unified these groups under a political unit, always ruled by a member of the Bushoong ethnicity. There is a political hierarchy amongst these groups that ensures that only certain members are able to hold power.

This hierarchy of power is explained via stories, presented as dramatic public performances, centered on three main characters: Moshambwooy/Woot (Fig. 7.9 left), Ngaady a Mwash (Fig. 7.9 right), and Bwoom (Fig. 7.9 center). Moshambwooy is the creator and Woot is the founder of the Kuba Kingdom (the first king). These two characters are embodied together in the performance via a mask that typically features an elephant trunk-like headdress and a beard (sometimes made of raffia; Kuba artists are widely known for their work with raffia) symbolizing wisdom and age. Cowrie shells adorn these masks as representations of status and wealth. Ngaady a Nwash is the ancestral maiden, represented in performances via an elegant mask with decorative face paint, distinct coiffure, and many cowrie shells. Bwoom is Woot’s competitor. Bwoom has distinctive facial features such as protruding forehead and chin, sunken cheeks, and a line of material (often beads) across his eyes, rendering him blind. See a photo of the entire Bwoom ensemble here.

Often held at initiation ceremonies and funerals, the performances of this mask triad enacts a story of kingly triumph. Woot and Bwoom compete for Ngaady a Mwash’s affections. Guess who wins… Woot (aligned with the creator god Moshambwooy) defeats Bwoom, becoming the first Kuba king and establishing the lineage of all Kuba kings to come after him. Woot is a member of the Bushoong ethnicity. This is the reason why only Bushoong men are eligible to be king. Some versions of the myth suggest that Bwoon is Woot’s brother.

Other versions and scholarly research suggest a different layer to this story. Bwoom’s facial features may associate him with the original occupants of Kuba Kingdom territory: the Twa people (Cornet 1978: 202). Like the Ituri Mbuti peoples discussed in “What is important to us?,” the Twa are a pygmy society. The protruding forehead and sunken cheeks of the Bwoom mask may be an exaggerated way to represent facial features that are sometimes seen among pygmy populations. The competition between Woot and Bwoom may be a metaphorized storytelling of the conflicts between the Bushoong and the Twa. We don’t know much at all about this conflict or what occurred between them. All we know is that the Kuba Kingdom developed, under Bushoong leadership, in lands originally occupied by Twa peoples who eventually became part of the Kuba Kingdom. This sounds a lot like a process of occupation and conquering. The story of the romantic hero of Woot defeating the different and inferior (and blind) Bwoom is a story that explains the current political situation. Scholar Jan Vansina (1987) wrote a book entitled The Children of Woot exploring this very topic. Every time the story is performed in public, the society is reminded about the foundations of power and, depending on the audience, their place in that hierarchy of power.

Let’s expand beyond the Kuba Kingdom to consider kingly stories elsewhere. Have you heard of the Shahnama? It is probably the most famous Persian poem ever, commonly called the Book or Story of Kings, written by Abu Al-Qaisn Firdausi from 977 to 1010 CE. This poem is based on the long-established stories of Pre-Islamic Persian Kings from mythical beginnings, semi-historical legendary heroes, and recorded narratives of the Sasanian kings (the Persian dynasty eventually conquered by early Muslim leaders in the late 600s CE). Firdausi composed the poem entirely in the Persian language as a way to immortalize Persian heritage.

Figure 7.10 illustrates a page of a famous copy of Firdausi’s Shahnama, known as the Great Mongol Shahnama. This illustrated manuscript was commissioned by Ilkhanid (aka Ilkhanate) leaders associated with the greater Mongol Empire in the mid 1300s CE. The painting depicts the most famous kingly hero of the Sasanian era: Bahram V (aka Bahram Gur).

Bahram Gur lived in the early 400s CE and his reign was centered at the Sasanian capital of Ctesiphon, Iran (Fig. 7.1). While he led a few conflicts with the Byzantines to the west and Kidarites to the east, Bahram Gur primarily is celebrated for his patronage of music, beneficence to his subjects, and his love of hunting. He particularly enjoyed hunting gurs (wild donkeys/onagers), thus his popular moniker.

Bahram Gur Slays a Dragon (Fig. 7.10) fantastically illustrates a mythical demonstration of Bahram Gur’s prowess and hunting skill. We view the hero from behind, in his bright blue robes and golden armor, with a prominent golden halo. He plunges a sword into the belly of a gray and red spotted dragon. The dragon’s head on the left points to the sky with its mouth open in apparent pain. The scaly serpent-like body of the dragon twists behind Bahram Gur, around a tree, and above Bahram’s horse at the far right. It appears that Bahram Gur had already felled the dragon using his bow and arrow before the fatal blow.

Bahram Gur certainly lived and hunted as a Sasanian king but he probably didn’t hunt dragons. This part of Firdausi’s story is one example of the hype and fantasy that kingly stories often accrue over time. The lesson here is clear: Bahram Gur was a badass and a Persian king to remember. A later manuscript of the Shahnama, commissioned by Safavid ruler Shah Tahmasp around 1525 CE, includes paintings of Bahram Gur and other famous Persian Shahs, such as Gayumars and his grandson Hushang, in a different style. “The Feast of Sada” events, as illustrated by Safavid court painted Sultan Muhammad, recall the mythical account of Hushang discovering fire after, of course, slaying a dragon.

Such mythical accounts can make kings seem like gods. If you remember from “What is Divine?”, there are many stories about gods and how we view them. Shakyamuni Buddha is a curious case because many see him as a god today but he wasn’t considered a god during his lifetime. As Buddhism spread into East and Southeast Asia, Buddha eventually transformed into various versions of divine beings. Shakyamuni Buddha’s eventual god-like persona often reflects the fact that he is thought to have had many more previous lives than most of us, over 500 by most accounts. The stories of Siddhartha’s previous lives are known as the Jataka tales (jataka literally means birth but refers to the many births, via reincarnation, of an individual within Buddhism). These stories are an important part of the canon of Buddhist literature, surviving in the Pali Canon of texts and other versions.

Dipankara Jataka (Fig. 7.11) depicts a previous life in which the Buddha met another Buddha, known as Dipankara Buddha, that came before him. You read that correctly! According to the Pali Canon, Shakyamuni Buddha was not the only Buddha! There were many before him! He is just the most recent. Dipankara Buddha lived much earlier than Siddhartha’s lifetime and is considered the immediate predecessor of Shakyamuni. In the sculpted panel, Dipankara Buddha is the largest figure, standing with a halo (symbolizing his enlightenment) and demonstrating the abhaya mudra. The man standing in front of Dipankara is Megha (aka Sumedha), one of the previous incarnations of Siddhartha. Megha throws flowers and fruits towards Dipankara, honoring him. Then, above and below the standing Megha, there are two additional depictions, one floating above with arms in a gesture of veneration, and the other hunched over at Dipankara’s feet. This scene depicts the story of Megha meeting Dipankara Buddha and receiving a prophecy foretelling that in a future lifetime, Megha will be reborn as a prince, eventually reach enlightenment, and become a Buddha himself.

Before we leave Dipankara and Megha, let’s look back at Shakyamuni Buddha (Fig. 4.10) in “What is Divine.” These sculptures were made around the same time and quite close to one another. Check the maps (Figs. 4.1 & 7.1) to see how close Mathura, India, and Gandhara, Pakistan, are. In comparing these two sculptures, do you notice the different material? Red sandstone was the common sculpting stone in Mathura while Gandharan artists used local gray schist. Do you notice the different representations of the robes and facial features? These differences relate to the influence that Gandhara felt from Classical Greek colonies in modern-day Afghanistan (what the Greeks called Bactria).

Established as a result of Alexander the Great’s incursions into Central Asia, the Greco-Bactrian Empire was thriving a couple centuries prior to the production of these sculptures. Greek art and culture were imported into the Greco-Bactrian Empire and filtered into surrounding regions, like Gandhara, through trade and exchange. The Greek descendants and governors of Bactria were later reconquered by Mauryan Emperor Ashoka and converted to Buddhism, contributing to the fusion of cultures over several hundred years. Of course, the full story of the origins and development of Gandharan art is far more complex. Delve deeper with “Inception of Gandhāra Sculpture” (Khan 1965).

The Gandharan artists depicted Dipankara, Megha, and the attendants around them in garments draped like Classical Greek robes. Facial features like high foreheads, straight noses, and square chins, along with thin mustaches, reflect the styles of Classical Greek portraiture. On the flip side, Shakyamuni Buddha (Fig. 4.10) from Mathura reflects native Indian styles of sculpture. The robe is presented with thick ribbing at the arm and only as incised detail on the chest. The facial features reflect native Indian preferences of a rounded chin, short forehead, and largely proportioned eyes. The Gandharan example demonstrates the early globalization of the image of the Buddha. Shakyamuni Buddha transformed again and again as new peoples found value in his teachings.

The spectacle of stories

Recall the Kuba Kingdom performance of Woot’s defeat of Bwoom. These performances were public displays of heritage and power. Performers wore those elaborate masks to take on the persona and mythology of those characters (only with permission of the current king, btw). Most societies have special traditions of performance involving theatrics, music, dance, spoken word, or a combination thereof. The costumes, the movement, the setting, and the sounds can all contribute to a spectacle that captivates an audience and ensures that the underlying message resonates with the community.

In ancient Vietnam, among the Đông Sơn (aka Lạc Việt) culture, bronze drums like the Ngọc Lũ Drum (Fig. 7.12) featured prominently in public rituals and performances. When struck, the drum would produce a deep resonance, similar to large bronze gongs. Drums like this one would have been used at funerals, feasts, and military events.

The Ngọc Lũ Drum is considered particularly important in Vietnam because of the concentric rings of figural designs on the striking surface (for more detail, check out drawings of the figural scenes provided by the Vietnam National Museum of History). Circling a central starburst, the first circle features ritually adorned figures and musicians playing drums! Other instruments are depicted, too, as well as activities of rice agriculture. A leader, the most elaborately dressed figure, appears to preside over a procession of musicians, some of whom play inside a roofed structure with streamers (their hairstyles may indicate they are women). The two larger concentric circles feature images of deer, hornbill birds, and crane egrets. Bird imagery, including feathers, features prominently in the procession scene as well. The specific nature of the rituals for which drums like the Ngọc Lũ example were played are difficult to reconstruct. But these decorative scenes offer great clues!

Across the Pacific and back in Mesoamerica, public performances of the historic and present-day Maya recall their ancient past and reflect the colonial traditions brought by the Spanish. The elaborate Late Classic Maya dance performance illustrated in the Vessel of the Dancing Lords (Fig. 7.5) continued, somewhat transformed, until Spanish contact. As briefly described in “Where Does Art Come From? An Introduction,” in Guatemala, the Spanish conquest started around 1524 CE and continued until 1697 CE when the fiercely independent Itza Maya were defeated. One of the first Maya groups to be contacted and colonized was the K’iche. This initiated a period of immense change and cultural loss, but not extinction. The present-day Maya still practice many of the ancient traditions, including performance of the Danza del Venado (Deer Dance).

Venado Mask (Fig. 7.13) is a contemporary example of a mask worn to represent the deer in a performance about hunting and the interrelationships of humans and animals. The deer is the largest bodied mammal in Mesoamerica and has been hunted by Maya peoples for thousands of years. The Danza del Venado represents the sacredness of the deer and the importance placed in this source of meat. Public performances of this dance were a communal expression of this importance and the fertility of the land from which the deer derive. ![]()

Scholars suggest that the original Danza del Venado incorporated actual deer skulls as masks. As Spanish missionaries worked to convert Maya peoples to Catholicism, the use of animal skulls in ceremonial performances was discouraged. Thus, Maya carvers developed designs for painted wooden deer masks. The adornments primarily reflect the imported traditions of Spanish dress and embroidery. Today, performers that represent the venado character in the Danza del Venado also wear garments that reflect the Spanish colonial tradition. View this video of a Danza del Venado performance in Cahabon Alta, Guatemala in 2007.

Did you notice the masks of the hunters in the video? Those masks can serve double duty. At certain times of year, they represent the hunters in the Danza del Venado and at other times of year, they are used for characters in the Baile de la Conquista (Dance of the Conquest) (Fig. 7.14). This performance was created by a Spanish missionary experimenting with ways to convert Maya people to Catholicism. He came to understand the importance of storytelling through dance and performance within Maya culture. Thus, he developed a dance telling the story of the Spanish conquest of the K’iche Maya, focused on the defeat of the K’iche King, Tecum Uman (Fig. 7.14 center). Other Maya characters include shamans and caciques (chiefs) (Fig. 7.14 right). The ultimate victory of the Spanish by Pedro de Alvarado (Fig. 7.14 left) symbolized the victory of the Catholic Church and cemented the presence of Catholicism in the lives of Maya people. The differences in skin tone among the masks in Figure 7.14 clearly demonstrate biased portrayals, with Alvarado’s hair covered in gold. After the success of the Baile de la Conquista, many dances were created by Catholic officials to celebrate patron saints of individual towns. All of these dances continue to be performed today.

K’iche Maker(s) of Chichicastanango, El Quiche, Guatemala. Tecum Uman Mask (center). ca. 1960 CE. Wood, pigment, 9 ½ x 7 ⅛ x 5 ⅞”.

K’iche Maker(s) of Chichicastanango, El Quiche, Guatemala. Cacique Mask (right). ca. 1970 CE. Wood, pigment, 8 x 8 x 5”.

UTA Guatemalan Mask Collection. Photos by Cheryl Mitchell; CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

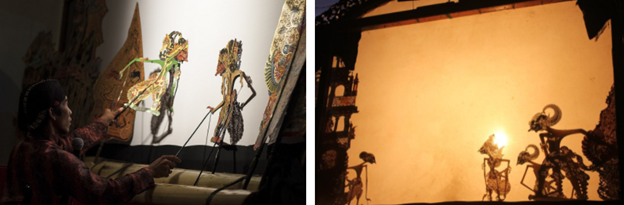

While performances primarily focused on the movement of the human body are common around the world, another form of performance also features prominently in many communities: puppetry. There are many forms of puppetry, including those using 3D puppet forms controlled via strings or with a puppeteer’s hand. Another form is shadow puppetry, wherein the puppeteer manipulates 2D puppets behind a screen and a light source projects the shadows of the puppets for the audience. Shadow puppetry can be traced across East Asia in China, Korea, and Japan. But in Southeast Asia, the tradition of Wayang Kulit of Java, Indonesia (Fig. 7.1), was probably influenced more by the puppetry traditions of India.

Figure 7.15 shows a dalang (Master Puppeteer of Java) performing a conflict scene between two male characters, depicted via painted buffalo hide puppets attached to buffalo horn or bamboo sticks. The Wayang Kulit puppets are designed with overlapping components and cut-out patterns so that the shadows they produce appear dimensionally and aesthetically complex. Set pieces of architectural facades (like that seen at the right of Figure 7.15) provide context for the scenes.

Wayang puppet shows feature music, voice actors, and dynamic stories often about Hindu mythologies and Javanese cultural legends. The drama is heightened because the shows are traditionally held from midnight to dawn. Check out historic photographs of Wayang shows and many examples of puppets here.

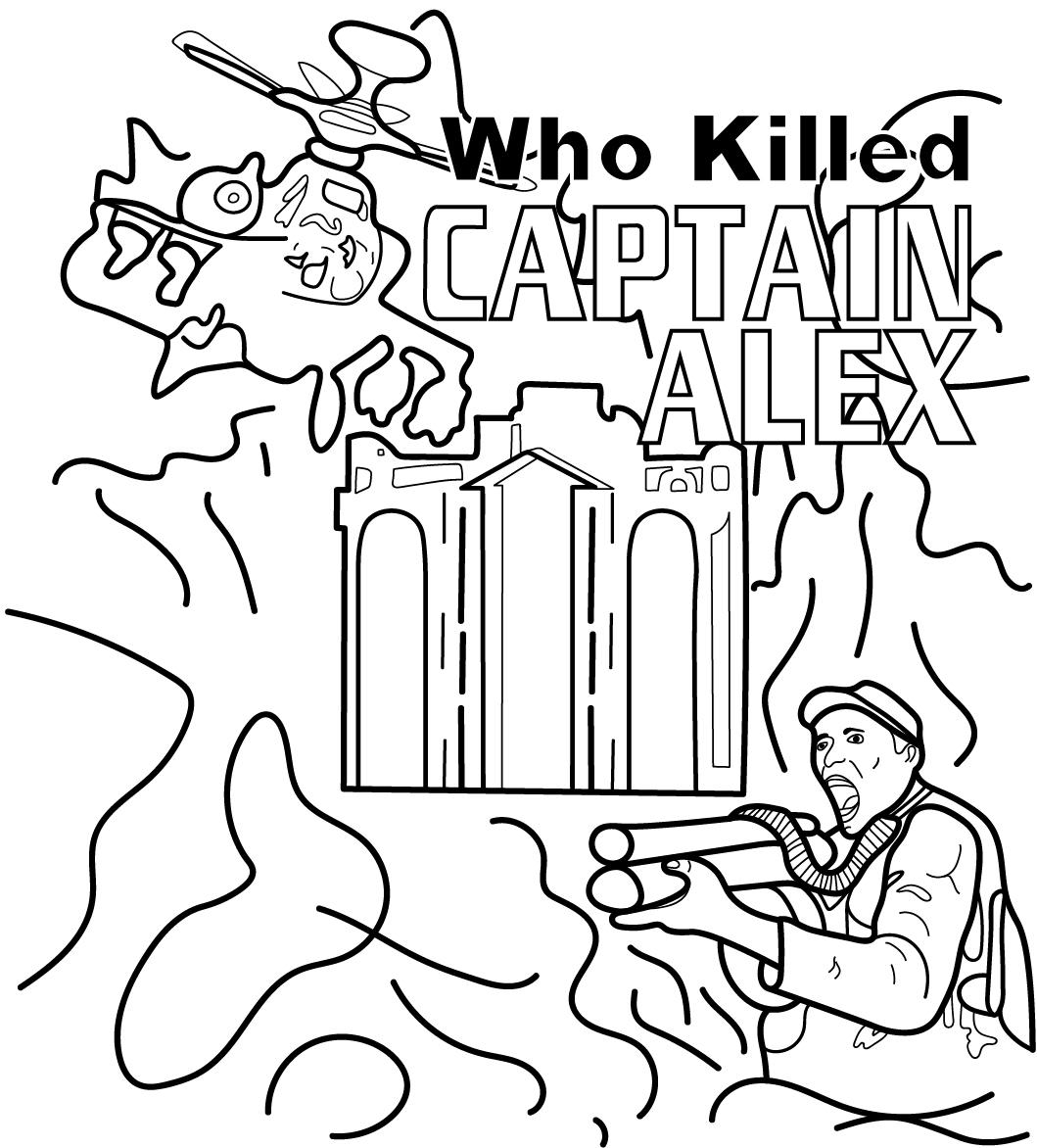

For our last excursion into stories, let’s go to the movies. We’re not going to Hollywood or Bollywood. We’re going to Wakaliwood. Wakaliga is an impoverished neighborhood of the Ugandan capital, Kampala. Isaac Nabwana established Ramon Film Productions in Wakaliga, popularly referred to as Wakaliwood, around 2005 CE. All original Wakaliwood films were extremely low-budget (like under $200) productions focused on do-it-yourself prop construction and development of local acting talent. Nabwana trained adults and children in Kung-Fu and other martial arts, using Asian cinematic classics as his guide. Hear about Nabwana’s journey from his own voice in “Meet the Steven Spielberg of Wakaliwood” from Great Big Story (Fig. 7.16).

Nabwana’s most famous film is Who Killed Captain Alex? from 2010 (original poster sketched in Fig. 7.17). Dubbed “Uganda’s First Action Movie,” the film’s storyline is as follows on IMDb:

Uganda’s president gives Captain Alex the mission to defeat the Tiger Mafia, but Alex gets killed in the process. Upon hearing the tragic news, his brother investigates to avenge Alex.

Wakaliwood films are often compared to the action films of Hollywood director Quentin Tarantino and Jean-Claude Van Damme. Martial arts sequences, gun battles, and chase scenes are common. Some viewers also find a dark comedic value in these films when the DIY props appear a bit too fake.

Films like Who Killed Captain Alex? were originally posted to YouTube for free. Nabwana also offered screenings of his films in Wakaliga for the local community. Today, Wakaliwood films are known around the world. Through social networks like a Kickstarter campaign, Nabwana has raised over $10,000 for certain projects. Bad Black has been a hit with international audiences, including those of the Seattle International Film Festival in 2017. These stories of action and (often quite violent) adventure demonstrate the value of using what you have and endeavoring to tell the stories that are the most interesting to you. As Nabwana says, “It is passion that really makes a movie [in Wakaliga]” (Venema 2015).

The Wrap-up

Stories are an integral part of the human experience, past and present. We engage with stories in so many different ways, from tv and film to grandma’s kitchen. All societies have stories that they hold dear and that they eventually seek to immortalize through visual storytelling. Art offers many different ways to express our stories and preserve the messages embedded within them. Think about the stories you want to ensure are preserved for future generations as you explore resources in the media and the scholarly literature below.

News Flash

- View an animated film illustrating the creation narrative of the Postclassic K’iche Maya creation narrative in the Popul Vuh.

- After watching Who Killed Captain Alex? check out the Wakaliwood: The Documentary also produced by Ramon Film Productions.

- To learn about Emily Kame Kngwarreye’s successful museum exhibition in Japan check out the documentary film “Emily in Japan.”

- To consider the bias and discrimination faced by Aboriginal Australians, watch this video produced by students and staff of The University of Sydney: “Ask us anything: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.”

- Check out the Shumla Archaeological Research and Education Center focused on documenting and protecting West Texas rock art for future generations, for which Dr. Carolyn Boyd is the founder and director.

Where Do I Go From Here? / The Bibliography

Boyd, Carolyn E. 2003. Rock Art of the Lower Pecos. College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

Khan, Muhammad W. 1964. Inception of Gandhāra Sculpture.” East and West 15, so. 1-2 (January):53-61. https://www.jstor.org/stable/29754868?seq=1.

Vansina, Jan. 1978. The Children of Woot. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.