3.2 Specific ethical issues to consider

Learning Objectives

- Define informed consent, and describe how it works

- Identify the unique concerns related to the study of vulnerable populations

- Differentiate between anonymity and confidentiality

- Explain the ethical responsibilities of social workers conducting research

- Identify the unique ethical concern posed by internet research

As should be clear by now, conducting research on humans presents a number of unique ethical considerations. Human research subjects must be given the opportunity to consent to their participation in research, fully informed of the study’s risks, benefits, and purpose. Further, subjects’ identities and the information they share should be protected by researchers. Of course, how consent and identity protection are defined may vary by individual researcher, institution, or academic discipline. In section 3.1, we examined the role that institutions play in shaping research ethics. In this section, we’ll take a look at a few specific topics that individual researchers and social workers in general must consider before embarking on research with human subjects.

Informed consent

A norm of voluntary participation is presumed in all social work research projects. In other words, we cannot force anyone to participate in our research without that person’s knowledge or consent (so much for that Truman Show experiment). Researchers must therefore design procedures to obtain subjects’ informed consent to participate in their research. Informed consent is defined as a subject’s voluntary agreement to participate in research based on a full understanding of the research and of the possible risks and benefits involved. Although it sounds simple, ensuring that one has actually obtained informed consent is a much more complex process than you might initially presume.

The first requirement is that, in giving their informed consent, subjects may neither waive nor even appear to waive any of their legal rights. Subjects also cannot release a researcher, her sponsor, or institution from any legal liability should something go wrong during the course of their participation in the research (USDHHS,2009). [1] Because social work research does not typically involve asking subjects to place themselves at risk of physical harm by, for example, taking untested drugs or consenting to new medical procedures, social work researchers do not often worry about potential liability associated with their research projects. However, their research may involve other types of risks.

For example, what if a social work researcher fails to sufficiently conceal the identity of a subject who admits to participating in a local swinger’s club? In this case, a violation of confidentiality may negatively affect the participant’s social standing, marriage, custody rights, or employment. Social work research may also involve asking about intimately personal topics, such as trauma or suicide that may be difficult for participants to discuss. Participants may re-experience traumatic events and symptoms when they participate in a study. Even if you are careful to fully inform your participants of all risks before they consent to the research process, you can probably empathize with participants thinking they could bear talking about a difficult topic and then finding it too overwhelming once they start. In cases like these, it is important for a social work researcher to have a plan to provide supports. This may mean providing referrals to counseling supports in the community or even calling the police if the participant is an imminent danger to themselves or others.

It is vital that social work researchers explain their mandatory reporting duties in the consent form and ensure participants understand them before they participate. Researchers should also emphasize to participants that they can stop the research process at any time or decide to withdraw from the research study for any reason. Importantly, it is not the job of the social work researcher to act as a clinician to the participant. While a supportive role is certainly appropriate for someone experiencing a mental health crisis, social workers must ethically avoid dual roles. Referring a participant in crisis to other mental health professionals who may be better able to help them is preferred.

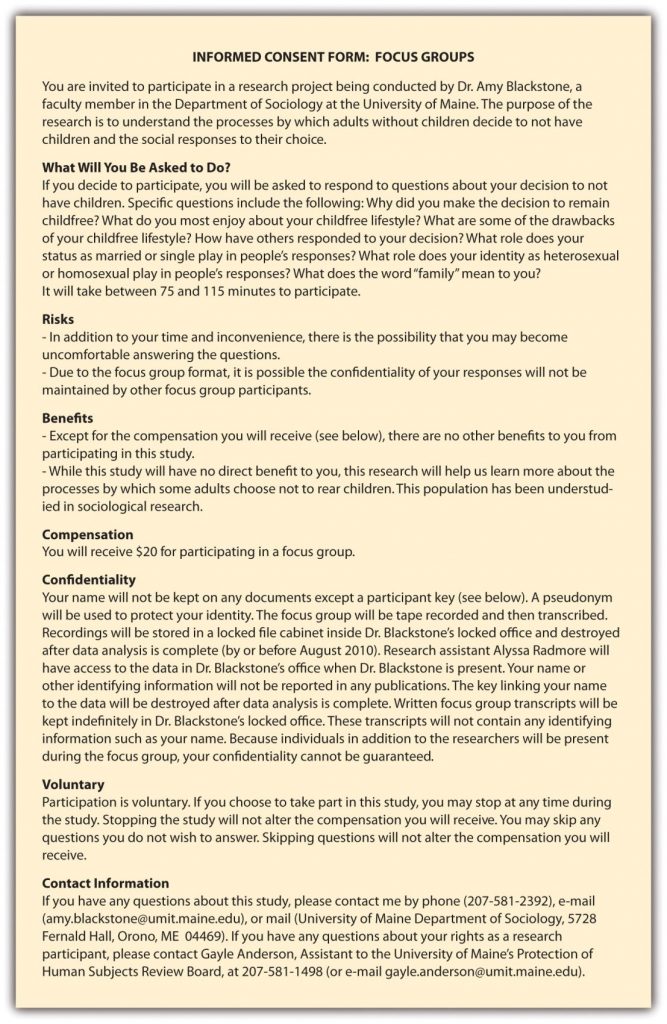

Beyond the legal issues, most IRBs require researchers to share some details about the purpose of the research, possible benefits of participation, and, most importantly, possible risks associated with participating in that research with their subjects. In addition, researchers must describe how they will protect subjects’ identities; how, where, and for how long any data collected will be stored; and whom to contact for additional information about the study or about subjects’ rights. All this information is typically shared in an informed consent form that researchers provide to subjects. In some cases, subjects are asked to sign the consent form indicating that they have read it and fully understand its contents. In other cases, subjects are simply provided a copy of the consent form and researchers are responsible for making sure that subjects have read and understand the form before proceeding with any kind of data collection. Figure 3.1 showcases a sample informed consent form from a research project on child-free adults. Note that this consent form describes a risk that may be unique to the particular method of data collection being employed: focus groups.

One last point to consider when preparing to obtain informed consent is that not all potential research subjects are considered equally competent or legally allowed to consent to participate in research. Subjects from vulnerable populations may be at risk of experiencing undue influence or coercion.[2] The rules for consent are more stringent for vulnerable populations. For example, minors must have the consent of a legal guardian in order to participate in research. In some cases, the minors themselves are also asked to participate in the consent process by signing special, age-appropriate “assent” forms designed specifically for them. Prisoners and parolees also qualify as vulnerable populations. Concern about the vulnerability of these subjects comes from the very real possibility that prisoners and parolees could perceive that they will receive some highly desired reward, such as early release, if they participate in research. Another potential concern regarding vulnerable populations is that they may be underrepresented in research, and even denied potential benefits of participation in research, specifically because of concerns about their ability to consent. So, on the one hand, researchers must take extra care to ensure that their procedures for obtaining consent from vulnerable populations are not coercive. The procedures for receiving approval to conduct research on these groups may be more rigorous than that for non-vulnerable populations. On the other hand, researchers must work to avoid excluding members of vulnerable populations from participation simply on the grounds that they are vulnerable or that obtaining their consent may be more complex. While there is no easy solution to this double-edged sword, an awareness of the potential concerns associated with research on vulnerable populations is important for identifying whatever solution is most appropriate for a specific case.

Protection of identities

As mentioned earlier, the informed consent process includes the requirement that researchers outline how they will protect the identities of subjects. This aspect of the process, however, is one of the most commonly misunderstood aspects of research.

In protecting subjects’ identities, researchers typically promise to maintain either the anonymity or confidentiality of their research subjects. Anonymity is the more stringent of the two. When a researcher promises anonymity to participants, not even the researcher is able to link participants’ data with their identities. Anonymity may be impossible for some social work researchers to promise because several of the modes of data collection that social workers employ. Face-to-face interviewing means that subjects will be visible to researchers and will hold a conversation, making anonymity impossible. In other cases, the researcher may have a signed consent form or obtain personal information on a survey and will therefore know the identities of their research participants. In these cases, a researcher should be able to at least promise confidentiality to participants.

Offering confidentiality means that some identifying information on one’s subjects is known and may be kept, but only the researcher can link participants with their data and she promises not to do so publicly. Confidentiality in research is quite similar to confidentiality in clinical practice. You know who your clients are, but others do not. You agree to keep their information and identity private. As you can see under the “Risks” section of the consent form in Figure 3.1, sometimes it is not even possible to promise that a subject’s confidentiality will be maintained. This is the case if data are collected in public or in the presence of other research participants (e.g., in the course of a focus group). Participants who social work researchers deem to be of imminent danger to self or others or those that disclose abuse of children and other vulnerable populations fall under a social worker’s duty to report. Researchers must then violate confidentiality to fulfill their legal obligations.

Protecting research participants’ identities is not always a simple prospect, especially for those conducting research on stigmatized groups or illegal behaviors. Sociologist Scott DeMuth learned that all too well when conducting his dissertation research on a group of animal rights activists. As a participant observer, DeMuth knew the identities of his research subjects. So when some of his research subjects vandalized facilities and removed animals from several research labs at the University of Iowa, a grand jury called on Mr. DeMuth to reveal the identities of the participants in the raid. When DeMuth refused to do so, he was jailed briefly and then charged with conspiracy to commit animal enterprise terrorism and cause damage to the animal enterprise (Jaschik, 2009).

Publicly, DeMuth’s case raised many of the same questions as Laud Humphreys’ work 40 years earlier. What do social scientists owe the public? Is DeMuth, by protecting his research subjects, harming those whose labs were vandalized? Is he harming the taxpayers who funded those labs? Or is it more important that DeMuth emphasize what he owes his research subjects, who were told their identities would be protected? DeMuth’s case also sparked controversy among academics, some of whom thought that as an academic himself, DeMuth should have been more sympathetic to the plight of the faculty and students who lost years of research as a result of the attack on their labs. Many others stood by DeMuth, arguing that the personal and academic freedom of scholars must be protected whether we support their research topics and subjects or not. DeMuth’s academic adviser even created a new group, Scholars for Academic Justice, to support DeMuth and other academics who face persecution or prosecution as a result of the research they conduct. What do you think? Should DeMuth have revealed the identities of his research subjects? Why or why not?

social work ethics and research

Often times, specific disciplines will provide their own set of guidelines for protecting research subjects and, more generally, for conducting ethical research. For social workers, the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) Code of Ethics section 5.02 describes the responsibilities of social workers in conducting research. Summarized below, these responsibilities are framed as part of a social worker’s responsibility to the profession. As representative of the social work profession, it is your responsibility to conduct and use research in an ethical manner.

A social worker should:

- Monitor and evaluate policies, programs, and practice interventions

- Contribute to the development of knowledge through research

- Keep current with the best available research evidence to inform practice

- Ensure voluntary and fully informed consent of all participants

- Not engage in any deception in the research process

- Allow participants to withdraw from the study at any time

- Provide access for participants to appropriate supportive services

- Protect research participants from harm

- Maintain confidentiality

- Report findings accurately

- Disclose any conflicts of interest

internet researcH

It is increasingly common for the internet to be used as a tool for conducting research and as a source of data such as the content of websites, blogs, or discussion boards. Research ethical principles apply to internet research, but there are ethical considerations that are unique to internet research.

Some of the major tensions and considerations of internet research include defining human subjects, differentiating between what is public and what is private, and making appropriate distinctions between individuals and data. These tensions lead to new concerns about informed consent, confidentiality, privacy, and harm when conducting internet research. These are important considerations because they link to the fundamental ethical principle of minimizing harm. Does the connection between one’s online data and his or her physical person enable psychological, economic, or physical, harm?

- Defining Human Subjects: In internet research, “human subject” has never been a good fit for describing many internet-based research environments. For example, should authors of web content be considered human subjects? This question is important because many regulatory bodies do not conduct ethical reviews if they determine that the research does not involve human subjects. Internet researchers have not reached a consensus about how to define the term “human subjects.” In fact, some contend that defining human subjects may not be as important as defining other terms such as harm, vulnerability, personally identifiable information, and so forth.

- Differentiating between Public and Private: Individual and cultural definitions and expectations of privacy are ambiguous, contested, and changing. On the internet, people may operate in public spaces but maintain strong perceptions or expectations of privacy. Or, they may acknowledge that the substance of their communication is public, but that the specific context in which it appears implies restrictions on how that information is – or should be – used by other parties. For example, a user may feel comfortable broadcasting tweets to a public audience, following the norms of the Twitter community. However, to find out that these ‘public’ tweets had been collected within a data set and combed over by a researcher could possibly feel like an encroachment on privacy. Despite what a simplified conceptualization of “public/private” might offer, there is no categorical way to discern all eventual harm. Data aggregators or search tools make information accessible to a wider public than what might have been originally intended. Social, academic, or regulatory delineations of public and private as a clearly recognizable binary no longer holds in everyday practice.

- Distinctions between individuals and data: The internet complicates the fundamental research ethics question of personhood. Is an avatar a person? Is one’s digital information an extension of the self? In the U.S. regulatory system, the primary question has generally been: Are we working with human subjects or not? If information is collected directly from individuals, such as an email exchange, instant message, or an interview in a virtual world, we are likely to naturally define the research scenario as one that involves a person. If the connection between the object of research and the person who produced it is indistinct, there may be a tendency to define the research scenario as one that does not involve any persons. This may oversimplify the situation–the question of whether one is dealing with a human subject is different from the question about whether information is linked to individuals: Can we assume a person is wholly removed from large data pools? For example, a data set containing thousands of tweets or an aggregation of surfing behaviors collected from a bot is perhaps far removed from the persons who engaged in these activities. In these scenarios, it is possible to forget that there was ever a person somewhere in the process that could be directly or indirectly impacted by the research. Yet there is considerable evidence that even ‘anonymized’ datasets that contain enough personal information can result in individuals being identifiable. Scholars and technologists continue to wrestle with how to adequately protect individuals when analyzing such datasets (Sweeny, 2009; Narayanan & Shmatikov, 2008, 2009).

These three issues represent ongoing tensions for internet research. Although researchers might like straightforward answers to questions such as “Will capturing a person’s Tweets cause them harm?” or “Is a blog a public or private space,” the uniqueness and almost endless range of specific situations has defied attempts to provide universal answers. The Association of Internet Researchers (Markham & Buchanan, 2012) has created a guide called Ethical Decision-Making and Internet Research that provides a detailed discussion of these issues.

Key Takeaways

- Researchers must obtain the informed consent of the people who participate in their research.

- Social workers must take steps to minimize the harms that could arise during the research process.

- If a researcher promises anonymity, she cannot link individual participants with their data.

- If a researcher promises confidentiality, she promises not to reveal the identities of research participants, even though she can link individual participants with their data.

- The NASW Code of Ethics includes specific responsibilities for social work researchers.

- Internet research is increasingly common and has its own unique set of ethical considerations.

Glossary

- Anonymity- the identity of research participants is not known to researchers

- Confidentiality- identifying information about research participants is known to the researchers but is not divulged to anyone else

- Informed consent- a research subject’s voluntary agreement to participate in a study based on a full understanding of the study and of the possible risks and benefits involved

Image attributions

Figure 3.1 is copied from Blackstone, A. (2012) Principles of sociological inquiry: Qualitative and quantitative methods. Saylor Foundation. Retrieved from: https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_principles-of-sociological-inquiry-qualitative-and-quantitative-methods/ Shared under CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 License

- The full set of requirements for informed consent can be read online at the Office for Human Research Protections. ↵

- The guidelines on vulnerable populations can be read online at the the US Department of Health and Human Services’. ↵