6.4 Critical thinking about samples

Learning Objectives

- Identify three questions you should ask about samples when reading research results

- Describe how bias impacts sampling

We read and hear about research results so often that we might sometimes overlook the need to ask important questions about where the research participants came from and how they are identified for inclusion. It is easy to focus only on findings when we’re busy and when the really interesting stuff is in a study’s conclusions, not its procedures. But now that you have some familiarity with the variety of procedures for selecting study participants, you are equipped to ask some very important questions about the findings you read and to be a more responsible consumer of research.

Who was sampled, how, and for what purpose?

Have you ever been a participant in someone’s research? If you have ever taken an introductory psychology or sociology class at a large university, that’s probably a silly question to ask. Social science researchers on college campuses have a luxury that researchers elsewhere may not share—they have access to a whole bunch of (presumably) willing and able human guinea pigs. But that luxury comes at a cost—sample representativeness. One study of top academic journals in psychology found that over two-thirds (68%) of participants in studies published by those journals were based on samples drawn in the United States (Arnett, 2008). Further, the study found that two-thirds of the work that derived from U.S. samples published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology was based on samples made up entirely of American undergraduates taking psychology courses.

These findings certainly raise the question: What do we actually learn from social scientific studies and about whom do we learn it? That is exactly the concern raised by Joseph Henrich and colleagues (Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, 2010), authors of the article “The Weirdest People in the World?” In their piece, Henrich and colleagues point out that behavioral scientists very commonly make sweeping claims about human nature based on samples drawn only from WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) societies, and often based on even narrower samples, as is the case with many studies relying on samples drawn from college classrooms. As it turns out, many robust findings about the nature of human behavior when it comes to fairness, cooperation, visual perception, trust, and other behaviors are based on studies that excluded participants from outside the United States and sometimes excluded anyone outside the college classroom (Begley, 2010). This certainly raises questions about what we really know about human behavior as opposed to U.S. resident or U.S. undergraduate behavior. Of course, not all research findings are based on samples of WEIRD folks. But even then, it would behoove us to pay attention to the population on which studies are based and the claims that are being made about to whom those studies apply.

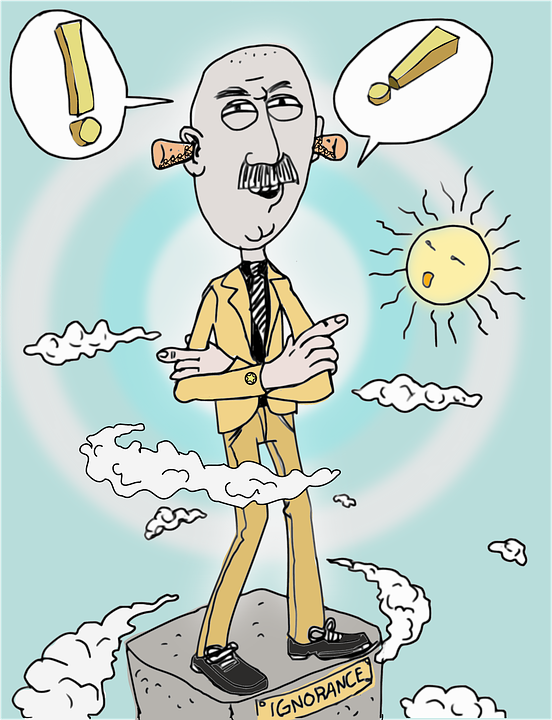

In the preceding discussion, the concern is with researchers making claims about populations other than those from which their samples were drawn. A related, but slightly different, potential concern is selection bias. Selection bias occurs when the elements selected for inclusion in a study do not represent the larger population from which they were drawn. For example, if you were to sample people walking into the social work building on campus during each weekday, your sample would include too many social work majors and not enough non-social work majors. Furthermore, you would completely exclude students whose classes are at night. Bias may be introduced by the sampling method used or due to conscious or unconscious bias introduced by the researcher (Rubin & Babbie, 2017). A researcher might select people who “look like good research participants,” in the process transferring their unconscious biases to their sample.

Another thing to keep in mind is that just because a sample may be representative in all respects that a researcher thinks are relevant, there may be aspects that are relevant that didn’t occur to the researcher when she was drawing her sample. You might not think that a person’s phone would have much to do with their voting preferences, for example. But had pollsters making predictions about the results of the 2008 presidential election not been careful to include both cell phone-only and landline households in their surveys, it is possible that their predictions would have underestimated Barack Obama’s lead over John McCain because Obama was much more popular among cell-only users than McCain (Keeter, Dimock, & Christian, 2008).

So how do we know when we can count on results that are being reported to us? While there might not be any magic or always-true rules we can apply, there are a couple of things we can keep in mind as we read the claims researchers make about their findings.

First, remember that sample quality is determined by the sample actually obtained, not by the sampling method itself. A researcher may set out to administer a survey to a representative sample by correctly employing a random selection technique, but if only a handful of the people sampled actually respond to the survey, the researcher will have to be very careful about the claims she can make about her survey findings.

Another thing to keep in mind, as demonstrated by the preceding discussion, is that researchers may be drawn to talking about implications of their findings as though they apply to some group other than the population actually sampled. Though this tendency is usually quite innocent and does not come from a place of malice, it is all too tempting a way to talk about findings; as consumers of those findings, it is our responsibility to be attentive to this sort of (likely unintentional) bait and switch.

Finally, keep in mind that a sample that allows for comparisons of theoretically important concepts or variables is certainly better than one that does not allow for such comparisons. In a study based on a nonrepresentative sample, for example, we can learn about the strength of our social theories by comparing relevant aspects of social processes. We talked about this as theory-testing in Chapter 4.

At their core, questions about sample quality should address who has been sampled, how they were sampled, and for what purpose they were sampled. Being able to answer those questions will help you better understand, and more responsibly read, research results.

Key Takeaways

- Sometimes researchers may make claims about populations other than those from whom their samples were drawn; other times they may make claims about a population based on a sample that is not representative. As consumers of research, we should be attentive to both possibilities.

- A researcher’s findings need not be generalizable to be valuable; samples that allow for comparisons of theoretically important concepts or variables may yield findings that contribute to our social theories and our understandings of social processes.

Glossary

- Selection bias- when the elements selected for inclusion in a study do not represent the larger population from which they were drawn due to sampling method or thought processes of the researcher