19.4 Phenomenology

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Begin to distinguish key features that are associated with phenomenological design

- Determine when a phenomenological study design may be a good fit for a qualitative research study

What is the purpose of phenomenology research?

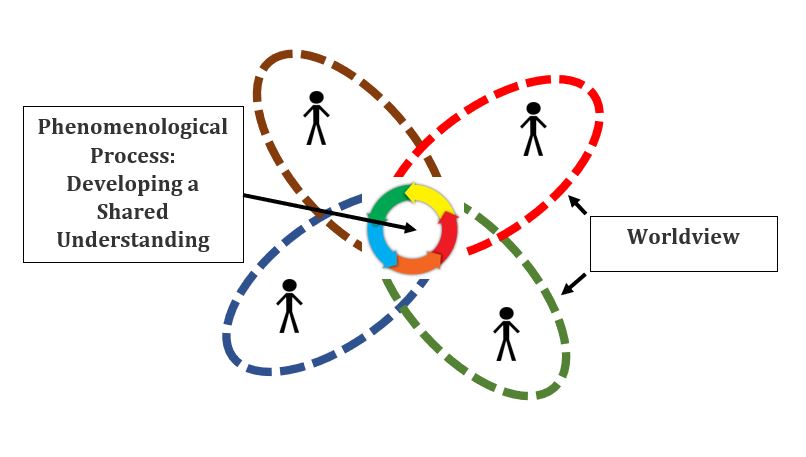

Phenomenology is concerned with capturing and describing the lived experience of some event or “phenomenon” for a group of people. One of the major assumptions in this vein of research is that we all experience and interpret our encounters with the world around us. Furthermore, we interpret these experiences from our own unique worldview, shaped by our beliefs, values and previous encounters. We then go on to attach our own meaning to them. By studying the meaning that people attach to their experiences, phenomenologists hope to understand these experiences in much richer detail. Ideally, this allows them to translate a unidimensional idea that they are studying into a multidimensional understanding that reflects the complex and dynamic ways we experience and interpret our world.

As an example, perhaps we want to study the experience of being a student in a social work research class, something you might have some first-hand knowledge with. Putting yourself into the role of a participant in this study, each of you has a unique perspective coming into the class. Maybe some of you are excited by school and find classes enjoyable; others may find classes boring. Some may find learning challenging, especially with traditional instructional methods; while others find it easy to digest materials and understand new ideas. You may have heard from your friends, who took this class last year, that research is hard and the professor is evil; while the student sitting next to you has a mother who is a researcher and they are looking forward to developing a better understanding of what she does. The lens through which you interpret your experiences in the class will likely shape the meaning you attach to it, and no two students will have the exact same experience, even though you all share in the phenomenon—the class itself. As a phenomenologist, I would want to try to capture how various students experienced the class. I might explore topics like: what did you think about the class, what feelings were associated with the class as a whole or different aspects of the class, what aspects of the class impacted you and how, etc. I would likely find similarities and differences across your accounts and I would seek to bring these together as themes to help more fully understand the phenomenon of being a student in a social work research class. From a more professionally practical standpoint, I would challenge you to think about your current or future clients. Which of their experiences might it be helpful for you to better understand as you are delivering services? Here are some general examples of phenomenological questions that might apply to your work:

- What does it mean to be part of an organization or a movement?

- What is it like to ask for help or seek services?

- What is it like to live with a chronic disease or condition?

- What do people go through when they experience discrimination based on some characteristic or ascribed status?

Just to recap, phenomenology assumes that…

- Each person has a unique worldview, shaped by their life experiences

- This worldview is the lens through which that person interprets and makes meaning of new phenomena or experiences

- By researching the meaning that people attach to a phenomenon and bringing individual perspectives together, we can potentially arrive at a shared understanding of that phenomenon that has more depth, detail and nuance than any one of us could possess individually.

What is involved in phenomenology research?

Again, phenomenological studies are best suited for research questions that center around understanding a number of different peoples’ experiences of particular event or condition, and the understanding that they attach to it. As such, the process of phenomenological research involves gathering, comparing, and synthesizing these subjective experiences into one more comprehensive description of the phenomenon. After reading the results of a phenomenological study, a person should walk away with a broader, more nuanced understanding of what the lived experience of the phenomenon is.

While it isn’t a hard and fast rule, you are most likely to use purposive sampling to recruit your sample for a phenomenological project. The logic behind this sampling method is pretty straightforward since you want to recruit people that have had a specific experience or been exposed to a particular phenomenon, you will intentionally or purposefully be reaching out to people that you know have had this experience. Furthermore, you may want to capture the perspectives of people with different worldviews on your topic to support developing the richest understanding of the phenomenon. Your goal is to target a range of people in your recruitment because of their unique perspectives.

For instance, let’s say that you are interested in studying the subjective experience of having a diagnosis of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). We might imagine that this experience would be quite different across time periods (e.g. the 1980’s vs. the 2010’s), geographic locations (e.g. New York City vs. the Kingdom of Eswatini in southern Africa), and social group (e.g. Conservative Christian church leaders in the southern US vs. sex workers in Brazil). By using purposive sampling, we are attempting to intentionally generate a varied and diverse group of participants who all have a lived experience of the same phenomenon. Of course, a purposive recruitment approach assumes that we have a working knowledge of who has encountered the phenomenon we are studying. If we don’t have this knowledge, we may need to use other non-probability approaches, like convenience or snowball sampling. Depending on the topic you are studying and the diversity you are attempting to capture, Creswell (2013) suggests that a reasonable sample size may range from 3 -25 participants for a phenomenological study. Regardless of which sample size you choose, you will want a clear rationale that supports why you chose it.

Most often, phenomenological studies rely on interviewing. Again, the logic here is pretty clear—if we are attempting to gather people’s understanding of a certain experience, the most direct way is to ask them. We may start with relatively unstructured questions: “can you tell me about your experience with…..”, “what was it it like to….”, “what does it mean to…”. However, as our interview progresses, we are likely to develop probes and additional questions, leading to a semi-structured feel, as we seek to better understand the emerging dimensions of the topic that we are studying. Phenomenology embodies the iterative process that has been discussed; as we begin to analyze the data and detect new concept or ideas, we will integrate that into our continuing efforts at collecting new data. So let’s say that we have conducted a couple of interviews and begin coding our data. Based on these codes, we decide to add new probes to our interview guide because we want to see if future interviewees also incorporate these ideas into how they understand the phenomenon. Also, let’s say that in our tenth interview a new idea is shared by the participant. As part of this iterative process, we may go back to previous interviewees to get their thoughts about this new idea. It is not uncommon in phenomenological studies to interview participants more than once. Of course, other types of data (e.g. observations, focus groups, artifacts) are not precluded from phenomenological research, but interviewing tends to be the mainstay.

In a general sense, phenomenological data analysis is about bringing together the individual accounts of the phenomenon (most often interview transcripts) and searching for themes across these accounts to capture the essence or description of the phenomenon. This description should be one that reflects a shared understanding as well as the context in which that understanding exists. This essence will be the end result of your analysis.

To arrive at this essence, different phenomenological traditions have emerged to guide data analysis, including approaches advanced by van Manen (2016)[1], Moustakas (1994)[2], Polikinghorne (1989)[3] and Giorgi (2009)[4]. One of the main differences between these models is how the researcher accounts for and utilizes their influence during the research process. Just like participants, it is expected in phenomenological traditions that the researcher also possesses their own worldview. The researcher’s worldview influences all aspects of the research process and phenomenology generally encourages the researcher to account for this influence. This may be done through activities like reflexive journaling (discussed in Chapter 20 on qualitative rigor) or through bracketing (discussed in Chapter 19 on qualitative analysis), both tools helping researchers capture their own thoughts and reactions towards the data and its emerging meaning. Some of these phenomenological approaches suggest that we work to integrate the researcher’s perspective into the analysis process, like van Manen; while others suggest that we need to identify our influence so that we can set it aside as best as possible, like Moustakas (Creswell, 2013).[5] For a more detailed understanding of these approaches, please refer to the resources listed for these authors in the box below.

Key Takeaways

- Phenomenology is a qualitative research tradition that seeks to capture the lived experience of some social phenomenon across some group of participants who have direct, first-hand experience with it.

- As a phenomenological researcher, you will need to bring together individual experiences with the topic being studied, including your own, and weave them together into a shared understanding that captures the “essence” of the phenomenon for all participants.

Exercises

Reflexive Journal Entry Prompt

- As you think about the areas of social work that you are interested in, what life experiences do you need to learn more about to help develop your empathy and humility as a social work practitioner in this field of practice?

Resources

To learn more about phenomenological research

Errasti‐Ibarrondo et al. (2018). Conducting phenomenological research: Rationalizing the methods and rigour of the phenomenology of practice.

Giorgi, A. (2009). The descriptive phenomenological method in psychology: A modified Husserlian approach. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

Koopman, O. (2015). Phenomenology as a potential methodology for subjective knowing in science education research.

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Newberry, A. M. (2012). Social work and hermeneutic phenomenology.

Polkinghorne, D. E. (1989). Phenomenological research methods. In R. S. Valle & S. Halling (Eds.). Existential-phenomenological perspectives in psychology (pp. 41-60). Boston, MA: Springer.

Seymour, T. (2019, January, 30). Phenomenological qualitative research design.

Van Manen, M. (2016). Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing. New York: Routledge.

For examples of phenomenological research

Curran et al. (2017). Practicing maternal virtues prematurely: The phenomenology of maternal identity in medically high-risk pregnancy.

Kang, S. K., & Kim, E. H. (2014). A phenomenological study of the lived experiences of Koreans with mental illness.

Pascal, J. (2010). Phenomenology as a research method for social work contexts: Understanding the lived experience of cancer survival.

- van Manen, M. (2016). Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing. New York: Routledge. ↵

- Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. ↵

- Polkinghorne, D. E. (1989). Phenomenological research methods. In R. S. Valle & S. Halling (Eds.). Existential-phenomenological perspectives in psychology (pp. 41-60). Boston, MA: Springer. ↵

- Giorgi, A. (2009). The descriptive phenomenological method in psychology: A modified Husserlian approach. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press. ↵

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). Los Angeles Sage. ↵

A qualitative research design that aims to capture and describe the lived experience of some event or "phenomenon" for a group of people.

In a purposive sample, participants are intentionally or hand-selected because of their specific expertise or experience.

also called availability sampling; researcher gathers data from whatever cases happen to be convenient or available

For a snowball sample, a few initial participants are recruited and then we rely on those initial (and successive) participants to help identify additional people to recruit. We thus rely on participants connects and knowledge of the population to aid our recruitment.

An iterative approach means that after planning and once we begin collecting data, we begin analyzing as data as it is coming in. This early analysis of our (incomplete) data, then impacts our planning, ongoing data gathering and future analysis as it progresses.

Often the end result of a phenomological study, this is a description of the lived experience of the phenomenon being studied.

A research journal that helps the researcher to reflect on and consider their thoughts and reactions to the research process and how it may be shaping the study

A qualitative research technique where the researcher attempts to capture and track their subjective assumptions during the research process. * note, there are other definitions of bracketing, but this is the most widely used.