6.2 Searching basics

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Brainstorm potential keywords and search queries for your topic

- Apply basic Boolean search operators to your search queries

- Identify relevant databases in which to search for journal articles

- Target your search queries in databases to the most relevant results

Pre-awareness check (Knowledge)

What are some search terms associated with your research topic? Imagine how you would search for information on your topic using Google or another typical search engine.

Training in research is beneficial because you will gain a deeper understanding of individuals, communities, and institutions. As you go through the book, you will be introduced to several evidence-based examples. It is important to discern the role and utility of research in improving existing programs or creating new ones for populations about which you are passionate. Learning the fundamentals of research will strengthen your analytical skills in dissecting complex social problems that persist in society.

This chapter will help you in searching, identifying, and gathering information to answer a particular question or problem. Think about how you gathered information about where to find the best pizza in town, the fastest/shortest route to school, or what the weather might look like for the day. Perhaps you looked on the internet, read reviews, browsed magazines, or asked your friends. Unlike day-to-day decisions, academic research, beginning with a literature review, is a systematic and organized process. It is based on empirical data and its goal is to verify or generate theories.

One of the drawbacks (or joys, depending on your perspective) of being a researcher in the 21st century is that we can do much of our work without ever leaving the comfort of our recliners. Although we may face some challenges to conducting research solely online including limited experimental research, participant access, and establishing trusting relationships with participants (Englund et al., 2022), much research can still be conducted effectively virtually. It is certainly true that you can familiarize yourself with the literature and find gaps in your knowledge in your area of interest, as most libraries offer incredible online search options and access to most of the literature you will ever need on your topic.

Unfortunately, even though many college classes require students to find and use academic journal articles, there is little training for students on how to do so. The purpose of this section and the rest of part 2 of the textbook is to build information literacy skills, which are the basic building blocks of any research project. While we describe the process here as linear, with one step following neatly after another, in reality, you will likely go back to Step 1 often as your topic gets more specific and your working question becomes clearer. [DOUBLE CHECK THIS IS STILL CORRECT]. Recall our diagram in an earlier chapter, Figure 2.1. You are cycling between reformulating your working question then searching for and reading the literature on your topic.

The process of searching databases and revising your working question can be time-consuming, so it is a good idea to write notes to yourself. Remembering why you included certain search terms, searched different databases, or other decisions in the literature search process can help you keep track of what you’ve done. You can then recreate searches to download articles you may have missed or remember reflections you had weeks ago when you last conducted a literature search. DeCarlo et al. (2020)[1] recommend creating a “working document” to capture notes and reflections when searching the literature.

Step 1: Build search queries using keywords

What do you type when you are searching for something on in a search engine like Google or Bing? Are you a question-asker? Do you type in full sentences or just a few keywords? What you type into a database or search engine is called a query. Well-constructed queries get you to the information you need more quickly, while unclear queries will force you to sift through dozens of irrelevant articles before you find the ones you want. The danger in being a question-asker or typing like you talk is that including too many extraneous words will confuse the search engine. In this section, you will learn to use keywords rather than natural language to find scholarly information.

Keywords are the words or phrases you use in your search query, and they inform the relevance and quantity of results you get. Unfortunately, different studies often use different terms to mean the same thing. A study may describe its topic as substance abuse, rather than addiction (for example). Think about what keywords are important to answering your working question. Are there other ways of expressing the same idea?

In social work research, there can be a bit of jargon to become familiar with when crafting your search queries. If you wanted to learn more about individuals of low socioeconomic status (SES) who do not have access to a bank account, you may need to learn the term “unbanked,” which refers to people without bank accounts. If you wanted to learn about children who take on parental roles in families, you may need to include the word “parentification” as part of your search query.

Exercises

TRACK 1 (IF YOU ARE CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

- List all of the keywords you can think of that are relevant to your working question.

- Add new keywords to this list as you are searching and learning more about your topic.

- Start a document in which you can put your keywords as well as your notes and reflections on the search process.

TRACK 2 (IF YOU AREN’T CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

- Pick a problem within your research topic (e.g., child welfare, mental health, school social work, veterans, reproductive health, services for individuals with an intellectual disability).

- With this problem, start to brainstorm key words that could be beneficial to include when searching the literature.

- Start a document in which you can put your keywords as well as your notes and reflections on the search process.

Boolean searching: Learn to talk like a robot

Google is a “natural language” search engine, which means it tries to use its knowledge of how people talk to better understand your query. Google’s academic database, Google Scholar, utilizes that same approach. However, other databases that are important for social work research—such as Academic Search Complete, PsycINFO, and PubMed—will not return useful results if you ask a question or type a sentence or phrase as your search query. Instead, these databases are best used by typing in keywords. Instead of typing “the effects of cocaine addiction on the quality of parenting,” you might type in “cocaine AND parenting” or “addiction AND child development.”

INSERT SCREEN SHOT HERE OF THE SEARCH EXAMPLES

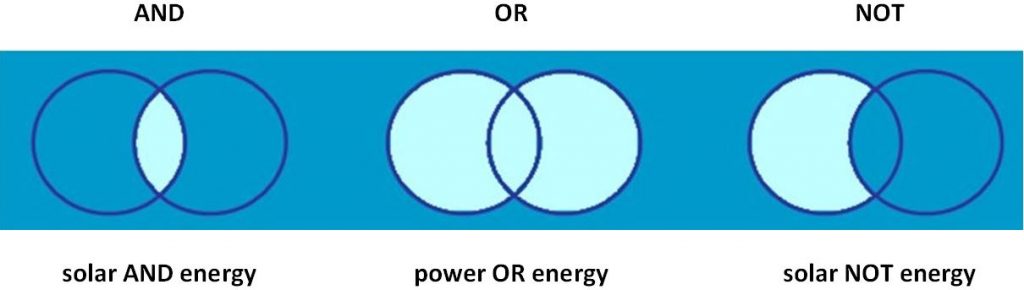

These operators (AND, OR, NOT) are part of what is called Boolean searching. Boolean searching works like a simple computer program. Your search query is made up of words connected by operators. Searching for “cocaine AND parenting” returns articles that mention both cocaine and parenting. There are lots of articles on cocaine and lots of articles on parenting, but fewer articles on that address both of those topics. In this way, the AND operator reduces the number of results you will get from your search query because both terms must be present.

The NOT operator also reduces the number of results you get from your query. For example, perhaps you wanted to exclude issues related to pregnancy. Searching for “cocaine AND parenting NOT pregnancy” would exclude articles that mentioned pregnancy from your results. Conversely, the OR operator would increase the number of results you get from your query. For example, searching for “cocaine OR parenting” would return not only articles that mentioned both words but also those that mentioned only one of your two search terms. This relationship is visualized in Figure 6.1 below.

Exercises

TRACK 1 & TRACK 2:

- Using the keywords from your list in the previous exercise, experiment with different Boolean search queries (AND, OR, and NOT).

- Continue to expand your search by swapping in different keywords.

- Write down which Boolean queries you create in your notes.

Step 2: Find the right databases

Queries are entered into a database or a searchable collection of information. In research methods, we are usually looking for databases that contain academic journal articles. Each database has a unique focus and presents distinct advantages or disadvantages. It is important to try out multiple databases, and experiment with different keywords and Boolean operators to find the most relevant results for your working question.

Google Scholar

The most commonly used public database of scholarly literature is Google Scholar, which offers many benefits. Building competence at using it will help you as you engage in literature searches. Because Google Scholar is a natural language search engine, it can seem less intimidating. However, Google Scholar also understands Boolean search terms and contains some advanced searching features like searching within one specific author’s body of work, one journal, or searching for keywords in the title of the journal. We have previously mentioned the ‘Cited By’ field which counts the number of other publications that cite the article and a link to explore and search within those citing articles. This can be helpful when you need to find more recent articles about the same topic.

You can link your personal Google account to your university login information to get one-click access to journal articles available at your institution through Google Scholar. Google Scholar’s citation generator can be quite helpful, though there are usually small revisions to make before using the recommended citation in a reference list. You can also set email alerts for a specific search query, which can help you stay current on the literature over time, and organize journal articles into folders. If these advanced features sound useful to you, consult Google Scholar Search Tips for a walkthrough.

While these features are great, there are some limitations to Google Scholar. The sources in Google Scholar are not curated by a professional body like the American Psychological Association (which curates PsycINFO). Instead, Google crawls the internet for what it thinks are scholarly works and indexes them in their database. When you search in Google Scholar, the sources will be not only journal articles, but books, government and foundation reports, gray literature, graduate theses, and articles that have not undergone peer review. There is no way to select for a specific type of source, and you need to look clearly and identify what kind of source you are reading. Not every source on Google Scholar is reputable or will match what you need for an assignment.

With that broad focus, Google Scholar ranks the results from your query by the number of times each source was cited by other scholars and the number of times your keywords are mentioned in the source. This biases the search results towards older, more foundational articles. So, you may want to consider limiting your results to only those published the last few years. Unfortunately, Google Scholar also lacks advanced searching features of other databases, like searching by subject area or within the abstract of an article.

Exercises

TRACK 1 & TRACK 2:

- Type your queries into Google Scholar. See which queries provide you with the most relevant results.

- Look for new keywords in the results you find, particularly any jargon used in that topic area you may not have known before.

- Write down notes on which queries and keywords work best. Reflect on what you read in the abstracts and titles of the search results in Google Scholar.

Databases accessed via an institution

Although learning Google Scholar is valuable, it is important to take advantage of the databases to which your institution purchases access. Two places to look for social work scholarship are the databases Social Service Abstracts and Social Work Abstracts, as these databases are indexed specifically for the discipline of social work. Because social work is interdisciplinary by nature, it is a good idea not to limit yourself solely to the social work literature on your topic. If your study requires information from the disciplines of psychology, education, or medicine, you will likely find the databases PsycINFO, ERIC, and PubMed (respectively) to be helpful in your search.

There are also less specialized databases that contain articles from across social work and other disciplines. Academic Search Complete is similar to Google Scholar in its breadth, as it contains a number of smaller databases from a variety of social science disciplines. Within Academic Search Complete, click Choose Databases to select databases that apply to different disciplines or topic areas.

It is worth mentioning that many university libraries have a meta-search engine which searches some of the databases to which they have access, including both disciplinary and interdisciplinary databases. Meta-search engines are fantastic, but it is important to narrow your results down to the type of resource you are looking for, as they will include all types of media (e.g., books, movies, games). Unfortunately, not every database is included in these meta-search engines, so you will likely want to try other databases, as well.

You can find the databases we mentioned here and others on the Databases page of your university library (see for example, this page of databases from the University of Texas at Arlington’s Libraries). A university login is required to access these databases because you pay for access as part of the tuition and fees at your university.

The databases we described here can be a bit more intimidating, as they have limited natural language support and rely mostly on Boolean searching. However, they contain more advanced search features which can help you narrow down your search to only the most relevant sources, our next step in the research process.

Exercises

TRACK 1 & TRACK 2:

- Explore different databases you can access via your university’s library website and searching using your keywords.

- Write notes on which databases and keywords provide you with the most relevant results and the disciplines you are likely to find in each database.

- Look for any new keywords in your results that will help you target your search, and experiment with new search queries.

Step 3: Reduce irrelevant search results

At this point, you may have worked on a few different search queries, swapped in and out different keywords, and explored a few different databases of academic journal articles relevant to your topic. Next, you have to deal with the most common frustration for students: narrowing down your search and reducing the number of results. Perhaps you’ve typed a query into Google Scholar or your library’s search engine and seen hundreds of thousands or millions of sources in your search results. Don’t worry! You don’t have to read all those articles to know enough about your topic area to produce a good research project.

While reading millions of articles is clearly ridiculous, there is no magic number of search results to reach. A good search will return results which are highly relevant. Reducing the number of results will save you time by eliminating irrelevant articles.

Here are two goals for reducing the number of results:

- Reduce the number of sources until you could reasonably skim through the title and abstract of each source. Generally, a hundred or a thousand results is manageable.

- Reduce the number of irrelevant sources in your search results until you are much more likely to encounter relevant articles. If only one of every ten results in your search is relevant to your topic, for example, it is a waste of time.

Here are some tips for reducing the number of irrelevant sources when you search in databases.

- Use quotation marks to indicate exact phrases, like “mental health” or “substance misuse.”

- Search for your keywords in the ABSTRACT. If your topic isn’t in the abstract, chances are the article isn’t relevant.

- Use SUBJECT headings to find relevant articles.

- Narrow down the years of publication. Unless you are gathering historical information about a topic, you are unlikely to find articles older than 10-15 years to be useful.

- Consult with a librarian. They are professional knowledge-gatherers, and there is often a librarian assigned to your department. Their job is to help you find what you need to know, and they are extensively trained in how to help you!

- Talk to your stakeholders or someone knowledgeable about your target population. They have lived experience with your topic which can help you understand the literature through a different lens. Moreover, the words they use to describe their experiences can also be useful sources of keywords, theories, studies, or jargon.

Exercises

TRACK 1 & TRACK 2:

- Using the techniques described in this subsection, reduce the number of irrelevant results in the database queries you have performed so far. Pay particular attention to searching within the abstract, using quotation marks to indicate keyword phrases, and exploring subject headings relevant to your topic.

- Reduce your database query results down to a number (a) where you could reasonably skim through the titles and abstracts to identify relevant articles and (b) where you are much more likely to encounter relevant articles. Repeat this process for your search of each database relevant to your project.

- Write down your queries or save them, so you can recreate them later if you need to return to them. Also, write down any reflections you have on the search process.

- Look for any new keywords in your results that will help you target your search better, and experiment with new search queries.

Step 4: Conduct targeted searches

Another way to save time when searching for literature is to look for articles that synthesize the results of other articles: review articles. Systematic reviews provide a summary of the existing literature on a topic. If you find one on your topic, you will be able to read one person’s summary of the literature and go deeper by reviewing and reading articles they cited in their references. Other types of reviews such as critical reviews may offer a viewpoint along with a birds-eye view of the literature.

Similarly, meta-analyses and meta-syntheses have long reference lists that are useful for finding additional sources on a topic. They use data from each article to run their own quantitative or qualitative data analysis. In this way, meta-analyses and meta-syntheses provide a more comprehensive overview of a topic. To find these kinds of articles, include the term “meta-analysis,” “meta-synthesis,” “scoping review,” or “systematic review” as keywords in your search queries.

It is good advice to read a review article first, as the purpose of review articles is to summarize an entire body of literature. This is exactly what students who are learning a new area need. Time is a precious resource for doctoral students, and review articles provide the most knowledge in the shortest time. Even if they are a few years old, they may help you understand what else you need to find in your literature search.

As you look through abstracts of articles in your search results, you will begin to notice that certain authors keep appearing. If you find an author that has written multiple articles on your topic, consider searching the AUTHOR field for that particular author. You can also search the web for that author’s Curriculum Vitae or CV (an academic resume) that will list their publications. Many authors maintain personal websites or host their CV on their university department’s webpage. Just type in their name and “CV” into a search engine. For example, you may find Michael Sherraden’s name often if your search query is about assets and poverty. You can find Michael Sherraden’s CV on the Washington University of St. Louis website.

A similar process can be used for journal names. As you are going through search results, you may also notice that many of the articles you’ve skimmed come from the same journals. Searching with that journal name in the JOURNAL field will allow you to narrow down your results to just that journal. For example, if you are searching for articles related to values and ethics in social work, you might want to search for articles in the Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics. You can do so within any database that indexes the journal, like Google Scholar, or through the search feature on the journal’s webpage. Browse the abstracts and download the full-text PDF of any article you think is relevant.

Step 5: Explore references and citations

The final step to make sure you didn’t miss anything is to look at the references in each article you cite. If there are articles that seem relevant to you, you may want to download them. Unfortunately, references may contain out-of-date material and cannot be updated after publication. As a result, a reference section for an article published in 2014 will only include references from pre-2014.

To find research published after 2014 on the same topic, you can use Google Scholar’s ‘Cited By’ feature to do a future-looking search. Look up your article on Google Scholar and click the ‘Cited By’ link. The results are a list of all the sources that cite the article you just read. Google Scholar also allows you to search within these articles—check the box below the search bar to do so—and it will search within the ‘Cited By’ articles for your keywords.

Exercises

TRACK 1 & TRACK 2:

- Examine the search results from various databases and look for authors and journals that publish often on your topic. Conduct targeted searches of these authors and journals to make sure you are not missing any relevant sources.

- Identify at least one relevant article, preferably a review article. Look in the references for any other sources relevant to your working question. Search for the article in Google Scholar and use the the ‘Cited By’ feature to look for additional sources relevant to your working question.

- Search for review articles that will help you get a broad sense of the literature. Depending on your topic, you may also want to look for other types of articles as well.

- Look for any new keywords in your results that will help you target your search, and experiment with new search queries.

- Write notes on your targeted searches, so you can recreate them later and remember your reflections on the search process.

Getting the right results

It is important to make an appointment with a librarian before coming to any conclusions on your research topic. They are highly trained professionals who can provide a great amount of assistance.

Let’s walk through an example. Imagine a local university wherein smoking was recently banned, much to the chagrin of a group of student smokers. Students were so upset by the idea that they would no longer be allowed to smoke on university grounds that they staged several smoke-outs during which they gathered in populated areas around campus and enjoyed a puff or two. Their activism was surprising. They were advocating for the freedoms of people committing a deviant act—smoking—that is highly disapproved of. Were the protesters otherwise politically active? How much effort and coordination had it taken to organize the smoke-outs?

The student researcher began their research by attempting to familiarize themselves with the literature. They started by looking to see if there were any other student smoke-outs using a simple Google search. When they turned to the scholarly literature, their search in Google Scholar for “college student activist smoke-outs,” yielded no results. Concluding there was no prior research on their topic, they informed the professor that they would not be able to write the required literature review since there was no literature for them to review. What went wrong here?

The student had been too narrow in their search for articles in their first attempt. They went back to Google Scholar and searched again using queries with different combinations of keywords. Rather than searching for “college student activist smoke-outs,” they tried “college student activism,” “smoke-out,” “protest,” and other keywords. This time their search yielded many articles. Of course, they were not all focused on pro-smoking activist efforts, but the results addressed their population of interest, college students, and on their broad topic of interest, activism. Experimenting with different keywords across different databases helped them get a comprehensive and multi-disciplinary view of the topic.

Reading articles on college student activism might give them some idea about what other researchers have found in terms of what motivates college students to become involved in activist efforts. They could also play around with their search terms and look for research on activism centered on other sorts of activities that are perceived by some to be perceived by some to be socially unacceptable, such as marijuana use or veganism. In other words, they needed to broaden their search about college student activism to include more than just smoke-outs and understand the theory and empirical evidence around student activism.

Once they searched for literature about student activism, they could link it to their specific research focus: smoke-outs organized by college student activists. What is true about activism broadly is not necessarily true of smoke-outs, as advocacy for smokers is unique from advocacy on other topics like environmental conservation. Engaging with the sociological literature about their target population, college students who smoke cigarettes, for example, helped to link the broader literature on advocacy to their specific topic area.

Revise your working question often

Throughout the process of creating and refining search queries, it is important to revisit your working question. In this example, trying to understand how and why the smoke-out took place is a good start to a working question, but it will likely need to be developed further to be more specific and concrete. Perhaps the researcher wants to understand how the protest was organized using social media and how social media impacts how students perceived the protests when they happened. This is a more specific question than “how and why did the smoke-out take place?” though you can see how the researcher started with a broad question and made it more specific by identifying one aspect of the topic to investigate in detail. You will find your working question shifting as you learn more about your topic and read more of the literature. This is an important sign that you are critically engaging with the literature and making progress. Though it can often feel like you are going in circles, there is no shortcut to figuring out what you need to know to study what you want to study.

Key Takeaways

- The quality of your search query determines the quality of your search results. If you don’t work on your queries, you’ll get a million results, only a small percentage of which are relevant to your project.

- Keywords and queries should be updated as you learn more about your topic.

- Your two goals in targeting your database searches should be reducing the number of results for each search query to a number you can feasibly skim and making those results more relevant to your project.

- Techniques to increase the number of relevant results in a search include using Boolean operators, quotation marks, searching in the abstract or title, and using subject headings.

- Use the databases that are most relevant to your topic. For general searches, Google Scholar has some strengths (ease of use, Cited By) and limitations (cannot search in abstract, includes resources other than journal articles). You can access other databases through your university’s library.

- Don’t be afraid to reach out to a librarian or your professor for help with searching. It is their job to help you.

Post-awareness check (Emotion)

What did you notice about how you felt when you were conducting your searches?

Exercises

TRACK 1 & TRACK 2:

- Reflect on your working question or research interest. Consider changes that would make it clearer and more specific based on the literature you have skimmed during your search.

- Describe how your search queries (across different databases) address your working question and provide a comprehensive view of the topic.

- Decarlo, M., Cummings, C., & Agnelli, K. (2020). Graduate research methods in social work. Open Social Work. https://pressbooks.rampages.us/msw-research ↵

search terms used in a database to find sources of information, like articles or webpages

the words or phrases in your search query

A Boolean search is a structured system that uses modifying terms (AND, OR, NOT) and symbols such as quotation marks and asterisks to modify, broaden, or restrict the search results

a searchable collection of information