18.5 Content analysis

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Explain defining features of content analysis as a strategy for analyzing qualitative data

- Determine when content analysis can be most effectively used

- Formulate an initial content analysis plan (if appropriate for your research proposal)

What are you trying to accomplish with content analysis

Much like with thematic analysis, if you elect to use content analysis to analyze your qualitative data, you will be deconstructing the artifacts that you have sampled and looking for similarities across these deconstructed parts. Also consistent with thematic analysis, you will be seeking to bring together these similarities in the discussion of your findings to tell a collective story of what you learned across your data. While the distinction between thematic analysis and content analysis is somewhat murky, if you are looking to distinguish between the two, content analysis:

- Places greater emphasis on determining the unit of analysis. Just to quickly distinguish, when we discussed sampling in Chapter 10 we also used the term “unit of analysis. As a reminder, when we are talking about sampling, unit of analysis refers to the entity that a researcher wants to say something about at the end of her study (individual, group, or organization). However, for our purposes when we are conducting a content analysis, this term has to do with the ‘chunk’ or segment of data you will be looking at to reflect a particular idea. This may be a line, a paragraph, a section, an image or section of an image, a scene, etc., depending on the type of artifact you are dealing with and the level at which you want to subdivide this artifact.

- Content analysis is also more adept at bringing together a variety of forms of artifacts in the same study. While other approaches can certainly accomplish this, content analysis more readily allows the researcher to deconstruct, label and compare different kinds of ‘content’. For example, perhaps you have developed a new advocacy training for community members. To evaluate your training you want to analyze a variety of products they create after the workshop, including written products (e.g. letters to their representatives, community newsletters), audio/visual products (e.g. interviews with leaders, photos hosted in a local art exhibit on the topic) and performance products (e.g. hosting town hall meetings, facilitating rallies). Content analysis can allow you the capacity to examine evidence across these different formats.

For some more in-depth discussion comparing these two approaches, including more philosophical differences between the two, check out this article by Vaismoradi, Turunen, and Bondas (2013).[1]

Variations in the approach

There are also significant variations among different content analysis approaches. Some of these approaches are more concerned with quantifying (counting) how many times a code representing a specific concept or idea appears. These are more quantitative and deductive in nature. Other approaches look for codes to emerge from the data to help describe some idea or event. These are more qualitative and inductive. Hsieh and Shannon (2005)[2] describe three approaches to help understand some of these differences:

- Conventional Content Analysis. Starting with a general idea or phenomenon you want to explore (for which there is limited data), coding categories then emerge from the raw data. These coding categories help us understand the different dimensions, patterns, and trends that may exist within the raw data collected in our research.

- Directed Content Analysis. Starts with a theory or existing research for which you develop your initial codes (there is some existing research, but incomplete in some aspects) and uses these to guide your initial analysis of the raw data to flesh out a more detailed understanding of the codes and ultimately, the focus of your study.

- Summative Content Analysis. Starts by examining how many times and where codes are showing up in your data, but then looks to develop an understanding or an “interpretation of the underlying context” (p.1277) for how they are being used. As you might have guessed, this approach is more likely to be used if you’re studying a topic that already has some existing research that forms a basic place to begin the analysis.

This is only one system of categorization for different approaches to content analysis. If you are interested in utilizing a content analysis for your proposal, you will want to design an approach that fits well with the aim of your research and will help you generate findings that will help to answer your research question(s). Make sure to keep this as your north star, guiding all aspects of your design.

Determining your codes

We are back to coding! As in thematic analysis, you will be coding your data (labeling smaller chunks of information within each data artifact of your sample). In content analysis, you may be using pre-determined codes, such as those suggested by an existing theory (deductive) or you may seek out emergent codes that you uncover as you begin reviewing your data (inductive). Regardless of which approach you take, you will want to develop a well-documented codebook.

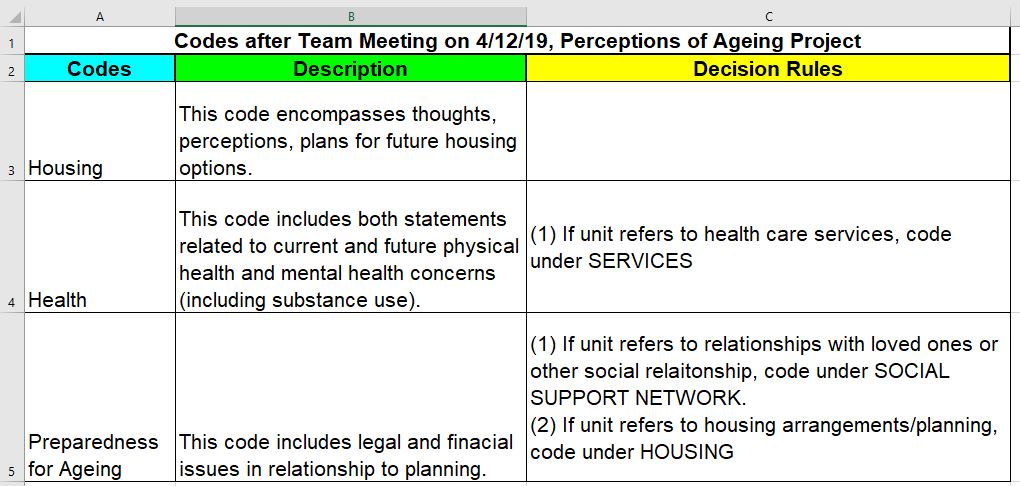

A codebook is a document that outlines the list of codes you are using as you analyze your data, a descriptive definition of each of these codes, and any decision-rules that apply to your codes. A decision-rule provides information on how the researcher determines what code should be placed on an item, especially when codes may be similar in nature. If you are using a deductive approach, your codebook will largely be formed prior to analysis, whereas if you use an inductive approach, your codebook will be built over time. To help illustrate what this might look like, Figure 18.12 offers a brief excerpt of a codebook from one of the projects I’m currently working on.

Coding, comparing, counting

Once you have (or are developing) your codes, your next step will be to actually code your data. In most cases, you are looking for your coding structure (your list of codes) to have good coverage. This means that most of the content in your sample should have a code applied to it. If there are large segments of your data that are uncoded, you are potentially missing things. Now, do note that I said most of the time. There are instances when we are using artifacts that may contain a lot of information, only some of which will apply to what we are studying. In these instances, we obviously wouldn’t be expecting the same level of coverage with our codes. As you go about coding you may change, refine and adapt your codebook as you go through your data and compare the information that reflects each code. As you do this, keep your research journal handy and make sure to capture and record these changes so that you have a trail documenting the evolution of your analysis. Also, as suggested earlier, content analysis may also involve some degree of counting as well. You may be keeping a tally of how many times a particular code is represented in your data, thereby offering your reader both a quantification of how many times (and across how many sources) a code was reflected and a narrative description of what that code came to mean.

Representing the findings from your coding scheme

Finally, you need to consider how you will represent the findings from your coding work. This may involve listing out narrative descriptions of codes, visual representations of what each code came to mean or how they related to each other, or a table that includes examples of how your data reflected different elements of your coding structure. However you choose to represent the findings of your content analysis, make sure the resulting product answers your research question and is readily understandable and easy-to-interpret for your audience.

Key Takeaways

- Much like thematic analysis, content analysis is concerned with breaking up qualitative data so that you can compare and contrast ideas as you look across all your data, collectively. A couple of distinctions between thematic and content analysis include content analysis’s emphasis on more clearly specifying the unit of analysis used for the purpose of analysis and the flexibility that content analysis offers in comparing across different types of data.

- Coding involves both grouping data (after it has been deconstructed) and defining these codes (giving them meaning). If we are using a deductive approach to analysis, we will start with the code defined. If we are using an inductive approach, the code will not be defined until the end of the analysis.

Exercises

Identify a qualitative research article that uses content analysis (do a quick search of “qualitative” and “content analysis” in your research search engine of choice).

- How do the authors display their findings?

- What was effective in their presentation?

- What was ineffective in their presentation?

Resources

Resources for learning more about Content Analysis

Bengtsson, M. (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis.

Colorado State University (n.d.) Writing@CSU Guide: Content analysis.

Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, Population Health. (n.d.) Methods: Content analysis

Mayring, P. (2000, June). Qualitative content analysis.

A few exemplars of studies employing Content Analysis

Collins et al. (2018). Content analysis of advantages and disadvantages of drinking among individuals with the lived experience of homelessness and alcohol use disorders.

Corley, N. A., & Young, S. M. (2018). Is social work still racist? A content analysis of recent literature.

Deepak et al. (2016). Intersections between technology, engaged learning, and social capital in social work education.

- Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15(3), 398-405. ↵

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277-1288. ↵

An approach to data analysis that seeks to identify patterns, trends, or ideas across qualitative data through processes of coding and categorization.

entity that a researcher wants to say something about at the end of her study (individual, group, or organization)

An approach to data analysis in which the researchers begins their analysis using a theory to see if their data fits within this theoretical framework (tests the theory).

An approach to data analysis in which we gather our data first and then generate a theory about its meaning through our analysis.

Part of the qualitative data analysis process where we begin to interpret and assign meaning to the data.

A document that we use to keep track of and define the codes that we have identified (or are using) in our qualitative data analysis.

A decision-rule provides information on how the researcher determines what code should be placed on an item, especially when codes may be similar in nature.

In qualitative data, coverage refers to the amount of data that can be categorized or sorted using the code structure that we are using (or have developed) in our study. With qualitative research, our aim is to have good coverage with our code structure.