4.4 Idiographic causal explanations

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Define and provide an example of an idiographic causal explanation

- Differentiate between idiographic and nomothetic causal explanations

- Link idiographic and nomothetic causal explanations with the process of theory building and theory testing

- Describe how idiographic and nomothetic causal explanations can be complementary

We began the previous section with a definition of causality, or the idea that “one event, behavior, or belief will result in the occurrence of another, subsequent event, behavior, or belief.” Then, we described one kind of causality: a generalizable cause-and-effect explanation as a nomothetic causal explanation.

But what if you are more interested in a cause-and-effect at a more individual level? Then, you need a different kind of causal explanation, one that accounts for the complexity of human interactions. This is what Chapter 5 covers: the process of inductively deriving theory from people’s stories and experiences. This process looks different than that depicted in Figure 4.8. It still starts with your research question and answering that question by conducting a research study. But instead of testing a hypothesis you created based on a theory, you will create a theory or explanations of your own that come from the data you collected. This format works well for qualitative research questions and for research questions that existing theories do not address.

What do idiographic causal explanations look like?

An idiographic causal explanation tries to identify the many, interrelated causes that account for the phenomenon the researcher is investigating. So, if idiographic causal explanations do not look like Figure 4.5, 4.6, or 4.7 what do they look like? Instead of saying “x causes y,” your participants will describe their experiences with “x,” which they will tell you was caused and influenced by a variety of other factors, as interpreted through their unique perspective, time, and environment. As we stated before, idiographic causal explanations are messy. Your job as a social science researcher is to accurately describe the patterns in what your participants tell you.

Let’s think about this using an example. If I asked you why you decided to become a social worker, what might you say? For me, I would say that I wanted to be a mental health clinician since I was in high school. I was interested in how people thought, and I was privileged enough to have psychology courses at my local high school. I thought I wanted to be a psychologist, but at my second internship in my undergraduate program, my supervisors advised me to become a social worker because the license provided greater authority for independent practice and flexibility for career change. Once I found out social workers were like psychologists who also raised trouble about social justice, I was hooked.

That’s not a simple explanation at all! But it’s definitely a causal explanation. It is my individual, subjective truth of a complex process. If we were to ask multiple social workers the same question, we might find out that many social workers begin their careers based on factors like personal experience with a disability or social injustice, positive experiences with social workers, or a desire to help others. No one factor is the “most important factor,” like with nomothetic causal associations. Instead, a complex web of factors, contingent on context, emerge when you interpret what people tell you about their lives.

Understanding “why?”

In creating an idiographic explanation, you are still asking “why?” But the answer is going to be more complex. Those complexities are described in Table 4.1 as well as this short video comparing nomothetic and idiographic explanations.

| Nomothetic causal explanations | Idiographic causal explanations | |

|---|---|---|

| Paradigm | Positivist | Constructivist |

| Purpose of research | Prediction & generalization | Understanding & particularity |

| Reasoning | Deductive | Inductive |

| Research methods | Quantitative | Qualitative |

| Causality | Simple: cause and effect | Complex: context-dependent, sometimes circular or contradictory |

| Role of theory | Theory testing | Theory building |

If you don’t want to generalize, you are trying to establish an idiographic causal explanation. The purpose of that explanation isn’t to predict the future or generalize to larger populations, but to describe the here-and-now as it is experienced by individuals within small groups and communities. Idiographic explanations are focused less on what is generally experienced by all people but more on the particularities of what specific individuals in a unique time and place experience.

Researchers seeking idiographic causal explanations are not trying to generalize or predict, so they have no need to reduce phenomena to mathematics. In fact, only examining things that can be counted can rob a causal association of its meaning and context. Instead, the goal of idiographic causal explanations is understanding, rather than prediction. Idiographic causal explanations are formed by interpreting people’s stories and experiences. Usually, these are expressed through words. Not all qualitative studies use word data, as some can use interpretations of visual or performance art. However, the vast majority of qualitative studies do use word data, like the transcripts from interviews and focus groups or documents like journal entries or meeting notes. Your participants are the experts on their lives—much like in social work practice—and as in practice, people’s experiences are embedded in their cultural, historical, and environmental context.

Idiographic causal explanations are powerful because they can describe the complicated and interconnected nature of human life. Nomothetic causal explanations, by comparison, are simplistic. Think about if someone asked you why you wanted to be a social worker. Your story might include a couple of vignettes from your education and early employment. It might include personal experience with the social welfare system or family traditions. Maybe you decided on a whim to enroll in a social work course during your graduate program. The impact of each of these events on your career is unique to you.

Idiographic causal explanations are concerned with individual stories, their idiosyncrasies, and the patterns that emerge when you collect and analyze multiple people’s stories. This is the inductive reasoning we discussed at the beginning of this chapter. Often, idiographic causal explanations begin by collecting a lot of qualitative data, whether through interviews, focus groups, or looking at available documents or cultural artifacts. Next, the researcher looks for patterns in the data and arrives at a tentative theory for how the key ideas in people’s stories are causally related.

Unlike nomothetic causal associations, there are no formal criteria (e.g., covariation) for establishing causality in idiographic causal explanations. In fact, some criteria like temporality and non-spuriousness may be violated. For example, if an adolescent client says, “It’s hard for me to tell whether my depression began before my drinking, but both got worse when I was expelled from my first high school,” they are recognizing that it may not so simple that one thing causes another. Sometimes, there is a reciprocal association where one variable (depression) impacts another (alcohol abuse), which then feeds back into the first variable (depression) and into other variables as well (school). Other criteria, such as covariation and plausibility, still make sense, as the association you highlight as part of your idiographic causal explanation should still be plausible and its elements should vary together.

Theory building and theory testing

As we learned in the previous section, nomothetic causal explanations are created by researchers applying deductive reasoning to their topic and creating hypotheses using social science theories. Much of what we think of as social science is based on this hypothetico-deductive method, but this leaves out the other half of the equation. Where do theories come from? Are they all just revisions of one another? How do any new ideas enter social science?

Through inductive reasoning and idiographic causal explanations!

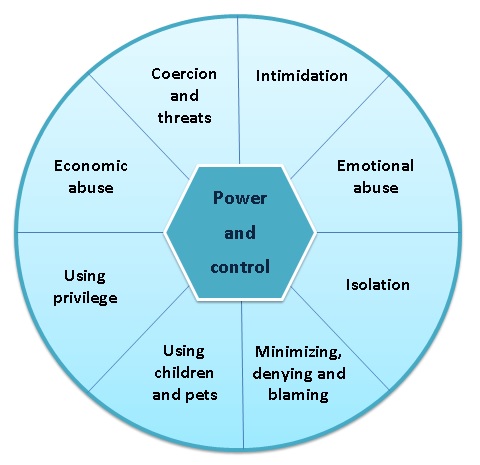

Let’s consider a social work example. If you plan to study domestic and sexual violence, you will likely encounter the Power and Control Wheel, also known as the Duluth Model (Figure 4.9). The wheel is a model designed to depict the process of domestic violence. The wheel was developed based on qualitative focus groups conducted by sexual and domestic violence advocates in Duluth, MN. This video explains more about the Duluth Model of domestic abuse.

The Power and Control Wheel is an example of what an idiographic causal explanation looks like. By contrast, look back at the previous section’s Figure 4.5, 4.6, and 4.7 on nomothetic causal associations between independent and dependent variables. See how much more complex idiographic causal explanations are?! They are complex, but not difficult to understand. At the center of domestic abuse is power and control, and while not every abuser would say that is what they were doing, that is the understanding of the survivors who informed this theoretical model. Their power and control are maintained through a variety of abusive tactics from social isolation to use of privilege to avoid consequences.

What about the role of hypotheses in idiographic causal explanations? In nomothetic causal explanations, researchers create hypotheses using existing theory and then test them for accuracy. There are generally not hypotheses in idiographic causality, but qualitative researchers begin their inquiries with ideas and observations about what they think might be true. Importantly, they address prior knowledge and biases before the project begins, but the goal of idiographic research is to let participants guide the process of knowledge building. Continuing with our Duluth Model example, advocates likely had some tentative hypotheses about what was important in a relationship with domestic violence. After all, they worked with this population for years prior to the creation of the model. However, it was the stories of the participants in these focus groups that led the Power and Control Wheel explanation for domestic abuse.

As qualitative inquiry unfolds, understandings are likely to emerge and shift as researchers learn from what their participants share. Because the participants are the experts in idiographic causal explanations, a researcher should be open to emerging topics and shift their research questions accordingly. This is in contrast to hypotheses in quantitative research, which remain constant throughout the study and are shown to be true or false.

Over time, as more qualitative studies are done and patterns emerge across different studies and locations, more sophisticated theories emerge that explain phenomena across multiple contexts. Once a theory is developed from qualitative studies, a quantitative researcher can seek to test that theory. For example, a quantitative researcher may hypothesize that men who hold traditional gender roles are more likely to engage in domestic violence. That would make sense based on the Power and Control Wheel model, as the category of “using male privilege” speaks to this association. In this way, qualitatively-derived theory can inspire a hypothesis for a quantitative research project, as we will explore in the next section.

Complementary approaches

If idiographic and nomothetic still seem like obscure philosophy terms, let’s consider another example. Imagine you are working for a community-based non-profit agency serving people with disabilities. You are putting together a report to lobby the state government for additional funding for community support programs. As part of that lobbying, you are likely to rely on both nomothetic and idiographic causal explanations.

If you looked at nomothetic explanations, you might learn how previous studies have shown that, in general, community-based programs like yours are linked with better health and employment outcomes for people with disabilities. Nomothetic causal explanations seek to establish that community-based programs result in improved outcomes for everyone with disabilities, including people in your community.

If you looked at idiographic causal explanations, you would use stories and experiences of people in community-based programs. These individual stories are full of detail about the lived experience of being in a community-based program. You might use one story from a client in your lobbying campaign, so policymakers can understand the lived experience of what it’s like to be a person with a disability in this program. For example, a client who said “I feel at home when I’m at this agency because they treat me like a family member,” or “this is the agency that helped me get my first paycheck,” can communicate richer, more complex causal explanations.

Neither kind of causal explanation is better than the other. A decision to seek idiographic causal explanations means that you will attempt to explain or describe your phenomenon exhaustively, attending to cultural context and subjective interpretations. A decision to seek nomothetic explanations, on the other hand, means that you will try to explain what is true for everyone and predict what will be true in the future. In short, idiographic explanations have greater depth, and nomothetic explanations have greater breadth.

Most importantly, social workers understand the value of both approaches to understanding the social world. A social worker helping a client with substance abuse issues seeks idiographic explanations when they ask about that client’s life story, investigate their unique physical environment, or probe how their family relationships. At the same time, a social worker also uses nomothetic explanations to guide their interventions. Nomothetic explanations may help guide them to minimize risk factors and maximize protective factors or use an evidence-based therapy, relying on knowledge about what in general helps people with substance abuse issues.

Now that you’ve been introduced to the concepts of nomothetic and idiographic causality, you may want to check out sociologist Bradley Wright’s humorous but informative blog post on types of causality.

So, which approach speaks to you? Are you interested in learning about (a) a few people’s experiences in a great deal of depth, or (b) a lot of people’s experiences more superficially, while also hoping your findings can be generalized to a greater number of people? The answer to this question will drive your research question and project. These approaches provide different types of information and both types are valuable.

Key Takeaways

- In quantitative studies, the goal is often to understand the more general causes of some phenomenon rather than the idiosyncrasies of one particular instance, as in an idiographic causal relationship.

- Idiographic causal explanations focus on subjectivity, context, and meaning.

- Idiographic causal explanations are best suited to qualitative methods.

- Idiographic causal explanations are used to create new theories in social science.

Exercises

TRACK 1 (IF YOU ARE CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

- Explore the literature on the theory you identified in section 4.1.

- Read about the origins of your theory. Who developed it and from what data?

- See if you can find a figure like Figure 4.9 in an article or book chapter that depicts the key concepts in your theory and how those concepts are related to one another causally.

- Write out a short statement on the causal explanation contained in the figure.

TRACK 2 (IF YOU AREN’T CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

You are interested in researching teen dating violence and teenagers’ levels of depressive symptoms and self-esteem.

- Explore the literature on the theory you identified in section 4.1.

- Read about the origins of your theory. Who developed it and from what data?

- See if you can find a figure like Figure 4.9 in an article or book chapter that depicts the key concepts in your theory and how those concepts are related to one another causally.

- Write out a short statement on the causal explanation contained in the figure.

attempts to explain or describe your phenomenon exhaustively, based on the subjective understandings of your participants