4.1 Inductive and deductive reasoning

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Describe inductive and deductive reasoning and provide examples of each

- Identify how inductive and deductive reasoning are complementary

Pre-awareness check (Emotion)

When you gain more knowledge, it is normal to experience discomfort as you question what you previously believed to be true. Have you experienced any internal struggles as you have been reading this text? Have any of your preconceived notions regarding your research topic been altered? Do you have any remaining challenges, biases, or blind spots that need to be addressed as you start this chapter?

[NEED AN INTRO TO THIS CHAPTER SECTION]

Inductive and deductive approaches to research are quite different, they can also be complementary. Let’s start by looking at each one and how they differ from one another. Then we’ll move on to thinking about how they complement one another.

Inductive reasoning

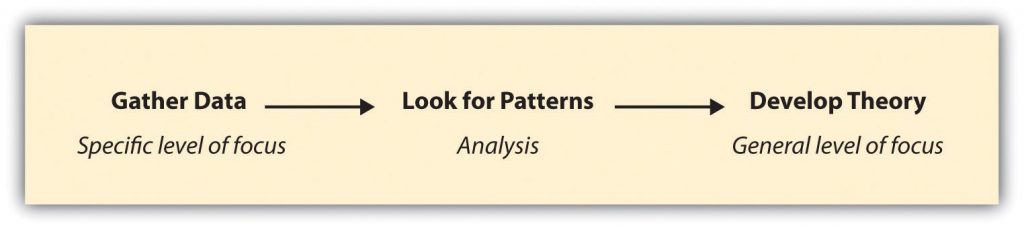

A researcher using inductive reasoning begins by collecting a substantial amount of data that is relevant to their topic of interest. The researcher will then step back from data collection to get a bird’s eye view of their data and look for patterns in the data, working to develop a theory that could explain those patterns. Thus, when researchers take an inductive approach, they start with a particular set of observations and move to a more general set of propositions about those experiences. In other words, they move from data to theory, or from the specific to the general. Figure 4.1 outlines the steps involved with an inductive approach to research.

There are many good examples of inductive research, but we’ll look at just a few here. One fascinating study in which the researchers took an inductive approach is Katherine Allen, Christine Kaestle, and Abbie Goldberg’s (2011)[1] study of how boys and young men learn about menstruation. To understand this process, Allen and her colleagues analyzed the written narratives of 23 young cisgender men in which the men described how they learned about menstruation, what they thought of it when they first learned about it, and what they think of it now. By looking for patterns across all 23 cisgender men’s narratives, the researchers were able to develop a general theory of how boys and young men learn about this aspect of girls’ and women’s biology. They conclude that sisters play an important role in boys’ early understanding of menstruation. Menstruation tends to make boys feel separated from girls, but as they gradually develop into adulthood and form romantic relationships, they simultaneously develop more mature attitudes about menstruation. Note how this study began with the data—men’s narratives of learning about menstruation—and worked to develop a theory.

In another inductive study, Kristin Ferguson and colleagues (Ferguson, Kim, & McCoy, 2011)[2] analyzed empirical data to better understand how to meet the needs of young people who are experiencing homelessness. The authors analyzed focus group data from 20 youth at a shelter. From the data they developed a set of recommendations for those interested in applied interventions that serve youth experiencing homelessness. The researchers also developed hypotheses for others who might wish to conduct further investigation of the topic. Though Ferguson and her colleagues did not test their hypotheses, their study ends where most deductive investigations begin: with a theory and a hypothesis derived from that theory. Section 4.4 discusses the use of mixed methods research as a way for researchers to test hypotheses created in a previous component of the same research project.

As in these examples, inductive reasoning is most commonly found in studies using qualitative methods, such as focus groups and interviews. Because inductive reasoning involves the creation of a new theory, researchers need very nuanced data on how the key concepts in their working research question operate in the real world. Qualitative data are often drawn from lengthy interactions and observations with the individuals and phenomena under examination. For this reason, inductive reasoning is most often associated with qualitative methods, though it is used in both quantitative and qualitative research.

Deductive reasoning

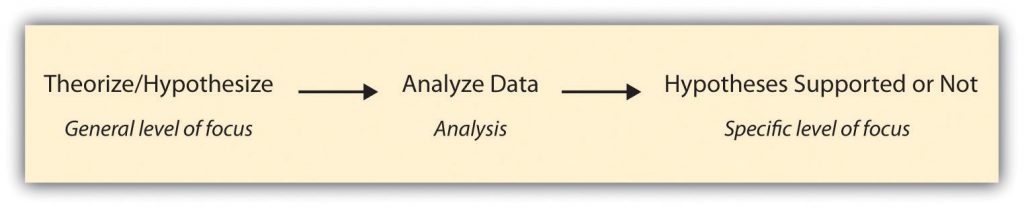

If inductive reasoning is about creating theories from raw data, deductive reasoning is about testing theories using data. Researchers using deductive reasoning take the steps described earlier for inductive research and reverse their order. They start with a compelling social theory, create a hypothesis about how the world should work, collect raw data, and analyze whether their hypothesis was confirmed or not. That is, deductive approaches move from a more general level (theory) to a more specific (data); whereas inductive approaches move from the specific (data) to general (theory).

Deductive approach to research are what many people think of when they think of scientific investigation. Students in English-dominant countries that may be confused by inductive vs. deductive research can rest part of the blame on Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of the Sherlock Holmes character. As Craig Vasey points out in his breezy introduction to logic book chapter, Sherlock Holmes more often used inductive rather than deductive reasoning (despite claiming to use the powers of deduction to solve crimes). By noticing subtle details in how people act, behave, and dress, Holmes finds patterns that others miss. Using those patterns, he creates a theory of how the crime occurred, dramatically revealed to the authorities just in time to arrest the suspect. Indeed, it is these flashes of insight into the patterns of data that make Holmes such a keen inductive reasoner. In social work practice, rather than detective work, inductive reasoning is supported by the intuitions and practice wisdom of social workers, just as Holmes’ reasoning is sharpened by his experience as a detective.

So, if deductive reasoning isn’t Sherlock Holmes’ observation and pattern-finding, how does it work? Figure 4.2 outlines the steps involved with a deductive approach to research.

While not all researchers follow a deductive approach, many do. We’ll now take a look at a couple examples of deductive research.

In a study of U.S. law enforcement responses to hate crimes, Ryan King and colleagues (King, Messner, & Baller, 2009)[3] hypothesized that law enforcement’s response would be less vigorous in areas of the country that had a stronger history of racial violence. The authors developed their hypothesis from prior research and theories on the topic. They tested the hypothesis by analyzing data on states’ lynching histories and hate crime responses. Overall, the authors found support for their hypothesis and illustrated an important application of critical race theory.

In another recent deductive study, Melissa Milkie and Catharine Warner (2011)[4] studied the effects of different classroom environments on first graders’ mental health. Based on prior research and theory, Milkie and Warner hypothesized that negative classroom features, such as a lack of basic supplies and heat, would be associated with emotional and behavioral problems in children. One might associate this research with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs or systems theory. The researchers found support for their hypothesis, demonstrating that policymakers should be paying more attention to the mental health outcomes of children’s school experiences, just as they track academic outcomes (American Sociological Association, 2011).[5]

Complementary approaches

While inductive and deductive approaches to research seem quite different, they can actually be rather complementary. In some cases, researchers will plan for their study to include multiple components, one inductive and the other deductive. In other cases, a researcher might begin a study with the plan to conduct either inductive or deductive research, but then discovers along the way that the other approach is needed to help illuminate findings. Here is an example of each such case.

Dr. Amy Blackstone (2012), author of Principles of sociological inquiry: Qualitative and quantitative methods, relates a story about her mixed methods research on sexual harassment.

We began the study knowing that we would like to take both a deductive and an inductive approach in our work. We therefore administered a quantitative survey, the responses to which we could analyze in order to test hypotheses, and also conducted qualitative interviews with a number of the survey participants. The survey data were well suited to a deductive approach; we could analyze those data to test hypotheses that were generated based on theories of harassment. The interview data were well suited to an inductive approach; we looked for patterns across the interviews and then tried to make sense of those patterns by theorizing about them.

For one paper (Uggen & Blackstone, 2004)[6], we began with a prominent feminist theory of the sexual harassment of adult women and developed a set of hypotheses outlining how we expected the theory to apply in the case of younger women’s and men’s harassment experiences. We then tested our hypotheses by analyzing the survey data. In general, we found support for the theory that posited that the current gender system, in which heteronormative men wield the most power in the workplace, explained workplace sexual harassment—not just of adult women but of younger women and men as well. In a more recent paper (Blackstone, Houle, & Uggen, 2006),[7] we did not hypothesize about what we might find but instead inductively analyzed interview data, looking for patterns that might tell us something about how or whether workers’ perceptions of harassment change as they age and gain workplace experience. From this analysis, we determined that workers’ perceptions of harassment did indeed shift as they gained experience and that their later definitions of harassment were more stringent than those they held during adolescence. Overall, our desire to understand young workers’ harassment experiences fully—in terms of their objective workplace experiences, their perceptions of those experiences, and their stories of their experiences—led us to adopt both deductive and inductive approaches in the work. (Blackstone, n.d., p. 21)[8]

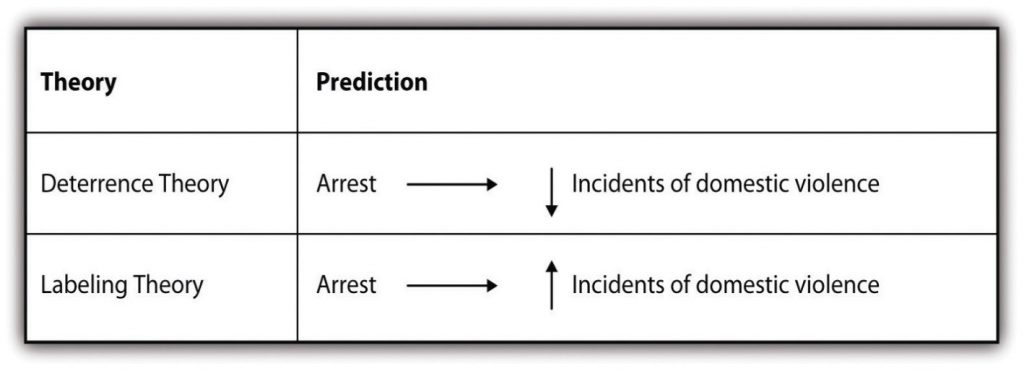

Researchers may not always set out to employ both approaches in their work but sometimes find that their use of one approach leads them to the other. One such example is described eloquently in Russell Schutt’s Investigating the Social World (2006).[9] As Schutt describes, researchers Sherman and Berk (1984)[10] conducted an experiment to test two competing theories of the effects of punishment on deterring deviance (in this case, domestic violence). Specifically, Sherman and Berk hypothesized that deterrence theory (see Williams, 2005[11] for more information on that theory) would provide a better explanation of the effects of arresting accused perpetrators than labeling theory. Deterrence theory predicts that arresting an accused perpetrators of domestic violence will reduce future incidents of violence. Conversely, labeling theory predicts that arresting alleged perpetrators will increase future incidents (see Policastro & Payne, 2013[12] for more information on that theory). Figure 4.3 summarizes the two competing theories and the hypotheses Sherman and Berk set out to test.

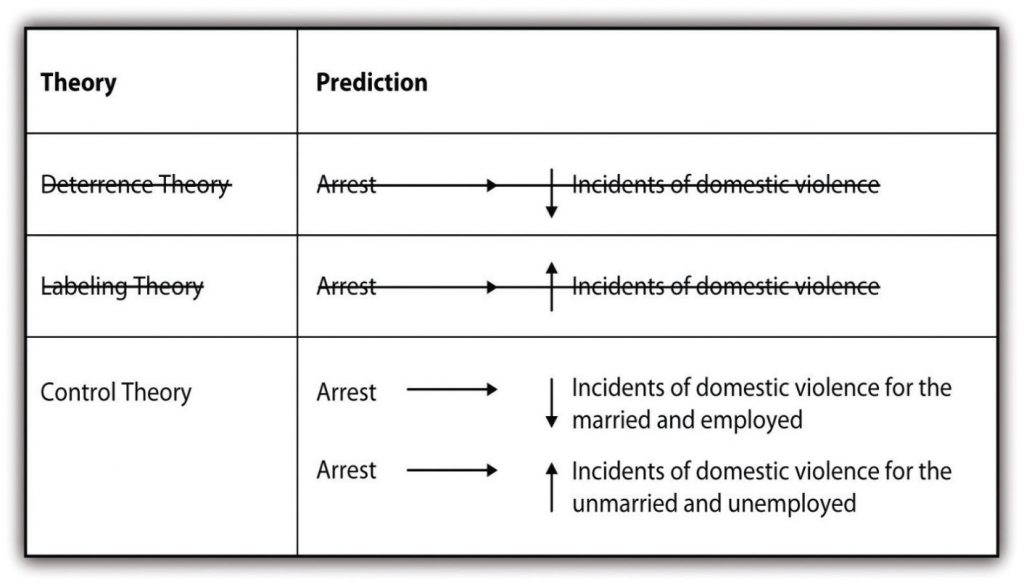

Sherman and Berk found, after conducting an experiment with the help of local police in one city, that arrest did in fact deter future incidents of violence, thus supporting their hypothesis that deterrence theory would better predict the effect of arrest. After conducting this research, they and other researchers went on to conduct similar experiments in six additional cities (Berk, Campbell, Klap, & Western, 1992; Pate & Hamilton, 1992; Sherman & Smith, 1992).[13]

Research from these follow-up studies were mixed. In some cases, arrest deterred future incidents of violence. In other cases, it did not. This left the researchers with new data that they needed to explain. The researchers therefore took an inductive approach in an effort to make sense of their latest empirical observations. The new studies revealed that arrest seemed to have a deterrent effect for those who were married and employed, but that it led to increased offenses for those who were unmarried and unemployed. Researchers thus turned to control theory, which posits that having some stake in conformity through the social ties provided by marriage and employment, as the better explanation (see Davis et al., 2000[14] for more information on this theory).

What the original Sherman and Berk study, along with the follow-up studies, show us is that we might start with a deductive approach to research, but then, if confronted by new data we must make sense of, we may move to an inductive approach. We will expand on these possibilities in section 4.5 when we discuss mixed methods research.

Ethical and critical considerations

Inductive and deductive reasoning, just like other components of the research process comes with ethical and cultural considerations for researchers. Specifically, deductive research is limited by existing theory. Because scientific inquiry has been shaped by oppressive forces such as sexism, racism, and colonialism, what is considered theory is largely based in Western, white-male-dominant culture. Thus, researchers doing deductive research may artificially limit themselves to ideas that were derived from this context. Non-Western researchers, international social workers, and practitioners working with non-dominant groups may find deductive reasoning of limited help if theories do not adequately describe other cultures.

While these flaws in deductive research may make inductive reasoning seem more appealing, on closer inspection you’ll find similar issues apply. A researcher using inductive reasoning applies their intuition and lived experience when analyzing participant data. They will take note of particular themes, conceptualize their definition, and frame the project using their unique psychology. Since everyone’s internal world is shaped by their cultural and environmental context, inductive reasoning conducted by Western researchers may unintentionally reinforcing lines of inquiry that derive from cultural oppression.

Inductive reasoning is also shaped by those invited to provide the data to be analyzed. For example, I recently worked with a student who wanted to understand the impact of child welfare supervision on children born dependent on opiates and methamphetamine. Due to the potential harm that could come from interviewing families and children who are in foster care or under child welfare supervision, the researcher decided to use inductive reasoning and to only interview child welfare workers.

Talking to practitioners is a good idea for feasibility, as they are less vulnerable than clients. However, any theory that emerges out of these observations will be substantially limited, as it would be devoid of the perspectives of parents, children, and other community members who could provide a more comprehensive picture of the impact of child welfare involvement on children. Notice that each of these groups has less power than child welfare workers in the service relationship. Attending to which groups were used to inform the creation of a theory and the power of those groups is an important critical consideration for social work researchers.

As you can see, when researchers apply theory to research they must wrestle with the history and hierarchy around knowledge creation in that area. In deductive studies, the researcher is positioned as the expert, similar to the positivist paradigm (which will be presented in Chapter 5). We’ve discussed a few of the limitations on the knowledge of researchers in this subsection, but the position of the “researcher as expert” is inherently problematic. However, it should also not be taken to an extreme. A researcher who approaches inductive inquiry as a naïve learner is also inherently problematic. Just as competence in social work practice requires a baseline of knowledge prior to entering practice, so does competence in social work research. Because a truly naïve intellectual position is impossible—we all have preexisting ways we view the world and are not fully aware of how they may impact our thoughts—researchers should be well-read in the topic area of their research study but humble enough to know that there is always much more to learn.

Key Takeaways

- Inductive reasoning begins with a set of empirical observations, seeking patterns in those observations, and then theorizing about those patterns.

- Deductive reasoning begins with a theory, developing hypotheses from that theory, and then collecting and analyzing data to test the truth of those hypotheses.

- Inductive and deductive reasoning can be employed together for a more complete understanding of the research topic.

- Though researchers don’t always set out to use both inductive and deductive reasoning in their work, they sometimes find that new questions arise in the course of an investigation that can best be answered by employing both approaches.

Exercises

TRACK 1 (IF YOU ARE CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

- Identify one theory and how it helps you understand your topic and working research question. Try to find a specific theory from this topic area, rather than relying only on the broad theoretical perspectives like systems theory or the strengths perspective. Those broad theoretical perspectives are okay, but searching for theories about your topic will help you conceptualize and design your research project.

- Using the theory you identified, describe what you expect the answer to be to your working research question.

TRACK 2 (IF YOU AREN’T CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

You are interested in researching teen dating violence and teenagers’ levels of depressive symptoms and self-esteem.

- Develop a working research question for this topic.

- Identify one theory and describe how it helps you understand your topic and working research question. Try to find a specific theory from this topic area, rather than relying only on the broad theoretical perspectives like systems theory or the strengths perspective. Those broad theoretical perspectives are okay, but searching for theories about your topic will help you conceptualize and design your research project.

- Using the theory you identified, describe what you expect the answer to be to your working research question.

- Allen, K. R., Kaestle, C. E., & Goldberg, A. E. (2011). More than just a punctuation mark: How boys and young men learn about menstruation. Journal of Family Issues, 32, 129–156. ↵

- Ferguson, K. M., Kim, M. A., & McCoy, S. (2011). Enhancing empowerment and leadership among homeless youth in agency and community settings: A grounded theory approach. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 28, 1–22 ↵

- King, R. D., Messner, S. F., & Baller, R. D. (2009). Contemporary hate crimes, law enforcement, and the legacy of racial violence. American Sociological Review, 74, 291–315. ↵

- Milkie, M. A., & Warner, C. H. (2011). Classroom learning environments and the mental health of first grade children. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52, 4–22. ↵

- The American Sociological Association wrote a press release on Milkie and Warner’s findings: American Sociological Association. (2011). Study: Negative classroom environment adversely affects children’s mental health. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/03/110309073717.htm ↵

- Uggen, C., & Blackstone, A. (2004). Sexual harassment as a gendered expression of power. American Sociological Review, 69, 64–92. ↵

- Blackstone, A., Houle, J., & Uggen, C. “At the time I thought it was great”: Age, experience, and workers’ perceptions of sexual harassment. Presented at the 2006 meetings of the American Sociological Association. ↵

- Blackstone, A. (2012). Inductive or deductive? Two different approaches. Principles of sociological inquiry: Qualitative and quantitative methods. Saylor Foundation. ↵

- Schutt, R. K. (2006). Investigating the social world: The process and practice of research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press. ↵

- Sherman, L. W., & Berk, R. A. (1984). The specific deterrent effects of arrest for domestic assault. American Sociological Review, 49, 261–272. ↵

- Williams, K. R. (2005). Arrest and intimate partner violence: Toward a more complete application of deterrence theory. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 10(6), 660-679. ↵

- Policastro, C., & Payne, B. K. (2013). The blameworthy victim: Domestic violence myths and the criminalization of victimhood. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 22(4), 329-347. ↵

- Berk, R., Campbell, A., Klap, R., & Western, B. (1992). The deterrent effect of arrest in incidents of domestic violence: A Bayesian analysis of four field experiments. American Sociological Review, 57, 698–708; Pate, A., & Hamilton, E. (1992). Formal and informal deterrents to domestic violence: The Dade county spouse assault experiment. American Sociological Review, 57, 691–697; Sherman, L., & Smith, D. (1992). Crime, punishment, and stake in conformity: Legal and informal control of domestic violence. American Sociological Review, 57, 680–690. ↵

- Taylor, B. G., Davis, R. C., & Maxwell, C. D. (2001). The effects of a group batterer treatment program: A randomized experiment in Brooklyn. Justice Quarterly, 18(1), 171-201. ↵

when a researcher starts with a set of observations and then moves from particular experiences to a more general set of propositions about those experiences

starts by reading existing theories, then testing hypotheses and revising or confirming the theory

a statement describing a researcher’s expectation regarding what they anticipate finding

when researchers use both quantitative and qualitative methods in a project