18.6 Grounded theory analysis

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Explain defining features of grounded theory analysis as a strategy for qualitative data analysis and identify when it is most effectively used

- Formulate an initial grounded theory analysis plan (if appropriate for your research proposal)

What are you trying to accomplish with grounded theory analysis

Just to be clear, grounded theory doubles as both qualitative research design (we will talk about some other qualitative designs in Chapter 22) and a type of qualitative data analysis. Here we are specifically interested in discussing grounded theory as an approach to analysis in this chapter. With a grounded theory analysis, we are attempting to come up with a common understanding of how some event or series of events occurs based on our examination of participants’ knowledge and experience of that event. Let’s consider the potential this approach has for us as social workers in the fight for social justice. Using grounded theory analysis we might try to answer research questions like:

- How do communities identity, organize, and challenge structural issues of racial inequality?

- How do immigrant families respond to threat of family member deportation?

- How has the war on drugs campaign shaped social welfare practices?

In each of these instances, we are attempting to uncover a process that is taking place. To do so, we will be analyzing data that describes the participants’ experiences with these processes and attempt to draw out and describe the components that seem quintessential to understanding this process.

Variations in the approach

Differences in approaches to grounded theory analysis largely lie in the amount (and types) of structure that are applied to the analysis process. Strauss and Corbin (2014)[1] suggest a highly structured approach to grounded theory analysis, one that moves back and forth between the data and the evolving theory that is being developed, making sure to anchor the theory very explicitly in concrete data points. With this approach, the researcher role is more detective-like; the facts are there, and you are uncovering and assembling them, more reflective of deductive reasoning. While Charmaz (2014)[2] suggests a more interpretive approach to grounded theory analysis, where findings emerge as an exchange between the unique and subjective (yet still accountable) position of the researcher(s) and their understanding of the data, acknowledging that another researcher might emerge with a different theory or understanding. So in this case, the researcher functions more as a liaison, where they bridge understanding between the participant group and the scientific community, using their own unique perspective to help facilitate this process. This approach reflects inductive reasoning.

Coding in grounded theory

Coding in grounded theory is generally a sequential activity. First, the researcher engages in open coding of the data. This involves reviewing the data to determine the preliminary ideas that seem important and potential labels that reflect their significance for the event or process you are studying. Within this open coding process, the researcher will also likely develop subcategories that help to expand and provide a richer understanding of what each of the categories can mean. Next, axial coding will revisit the open codes and identify connections between codes, thereby beginning to group codes that share a relationship. Finally, selective or theoretical coding explores how the relationships between these concepts come together, providing a theory that describes how this event or series of events takes place, often ending in an overarching or unifying idea tying these concepts together. Dr. Tiffany Gallicano[3] has a helpful blog post that walks the reader through examples of each stage of coding. Table 18.13 offers an example of each stage of coding in a study examining experiences of students who are new to online learning and how they make sense of it. Keep in mind that this is an evolving process and your document should capture this changing process. You may notice that in the example “Feels isolated from professor and classmates” is listed under both axial codes “Challenges presented by technology” and “Course design”. This isn’t an error; it just represents that it isn’t yet clear if this code is most reflective of one of these two axial codes or both. Eventually, the placement of this code may change, but we will make sure to capture why this change is made.

| Open Codes | Axial Codes | Selective |

| Anxious about using new tools | Challenges presented by technology | Doubts, insecurities and frustration experienced by new online learners |

| Lack of support for figuring technology out | ||

| Feels isolated from professor and classmates | ||

| Twice the work—learn the content and how to use the technology | ||

| Limited use of teaching activities (e.g. “all we do is respond to discussion boards”) | Course design | |

| Feels isolated from professor and classmates | ||

| Unclear what they should be taking away from course work and materials | ||

| Returning student, feel like I’m too old to learn this stuff | Learner characteristics | |

| Home feels chaotic, hard to focus on learning |

Constant comparison

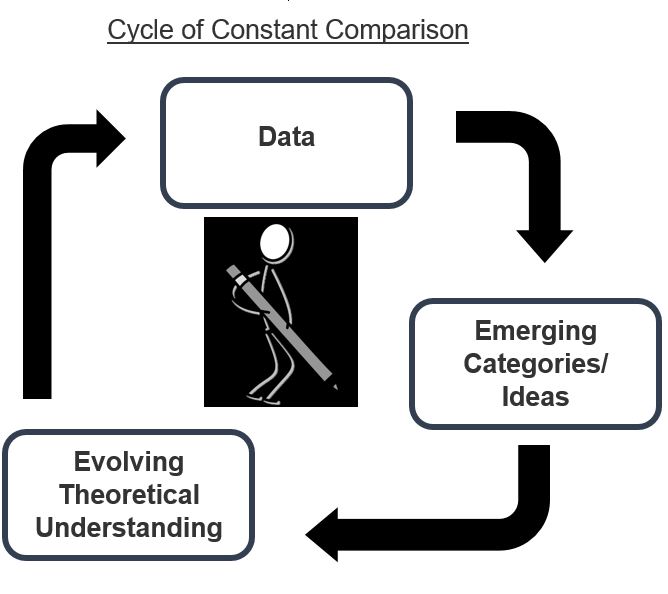

While ground theory is not the only approach to qualitative analysis that utilizes constant comparison, it is certainly widely associated with this approach. Constant comparison reflects the motion that takes place throughout the analytic process (across the levels of coding described above), whereby as researchers we move back and forth between the data and the emerging categories and our evolving theoretical understanding. We are continually checking what we believe to be the results against the raw data. It is an ongoing cycle to help ensure that we are doing right by our data and helps ensure the trustworthiness of our research. Ground theory often relies on a relatively large number of interviews and usually will begin analysis while the interviews are ongoing. As a result, the researcher(s) work to continuously compare their understanding of findings against new and existing data that they have collected.

Developing your theory

Remember, the aim of using a grounded theory approach to your analysis is to develop a theory, or an explanation of how a certain event/phenomenon/process occurs. As you bring your coding process to a close, you will emerge not just with a list of ideas or themes, but an explanation of how these ideas are interrelated and work together to produce the event you are studying. Thus, you are building a theory that explains the event you are studying that is grounded in the data you have gathered.

Thinking about power and control as we build theories

I want to bring the discussion back to issues of power and control in research. As discussed early in this chapter, regardless of what approach we are using to analyze our data we need to be concerned with the potential for abuse of power in the research process and how this can further contribute to oppression and systemic inequality. I think this point can be demonstrated well here in our discussion of grounded theory analysis. Since grounded theory is often concerned with describing some aspect of human behavior: how people respond to events, how people arrive at decisions, how human processes work. Even though we aren’t necessarily seeking generalizable results in a qualitative study, research consumers may still be influenced by how we present our findings. This can influence how they perceive the population that is represented in our study. For example, for many years science did a great disservice to families impacted by schizophrenia, advancing the theory of the schizophrenogenic mother[4]. Using pseudoscience, the scientific community misrepresented the influence of parenting (a process), and specifically the mother’s role in the development of the disorder of schizophrenia. You can imagine the harm caused by this theory to family dynamics, stigma, institutional mistrust, etc. To learn more about this you can read this brief but informative editorial article by Anne Harrington in the Lancet.[5] Instances like these should haunt and challenge the scientific community to do better. Engaging community members in active and more meaningful ways in research is one important way we can respond. Shouldn’t theories be built by the people they are meant to represent?

Key Takeaways

- Ground theory analysis aims to develop a common understanding of how some event or series of events occurs based on our examination of participants’ knowledge and experience of that event.

- Using grounded theory often involves a series of coding activities (e.g. open, axial, selective or theoretical) to help determine both the main concepts that seem essential to understanding an event, but also how they relate or come together in a dynamic process.

- Constant comparison is a tool often used by qualitative researchers using a grounded theory analysis approach in which they move back and forth between the data and the emerging categories and the evolving theoretical understanding they are developing.

Resources

Resources for learning more about Grounded Theory

Chun Tie, Y., Birks, M., & Francis, K. (2019). Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers.

Gibbs, G.R. (2015, February 4). A discussion with Kathy Charmaz on Grounded Theory.

Glaser, B.G., & Holton, J. (2004, May). Remodeling grounded theory.

Mills, J., Bonner, A., & Francis, K. (2006). The development of Constructivist Grounded Theory.

A few exemplars of studies employing Grounded Theory

Burkhart, L., & Hogan, N. (2015). Being a female veteran: A grounded theory of coping with transitions.

Donaldson, W. V., & Vacha-Haase, T. (2016). Exploring staff clinical knowledge and practice with LGBT residents in long-term care: A grounded theory of cultural competency and training needs.

Vanidestine, T., & Aparicio, E. M. (2019). How social welfare and health professionals understand “Race,” Racism, and Whiteness: A social justice approach to grounded theory.

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage publications. ↵

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. Sage Publications ↵

- Gallicano, T. (2013, July 22). An example of how to perform open coding, axial coding and selective coding. [Blog post]. https://prpost.wordpress.com/2013/07/22/an-example-of-how-to-perform-open-coding-axial-coding-and-selective-coding/ ↵

- Harrington, A. (2012). The fall of the schizophrenogenic mother. The Lancet, 379(9823), 1292-1293. ↵

- Harrington, A. (2012). The fall of the schizophrenogenic mother. The Lancet, 379(9823), 1292-1293. ↵

A form of qualitative analysis that aims to develop a theory or understanding of how some event or series of events occurs by closely examining

participant knowledge and experience of that event(s).

starts by reading existing theories, then testing hypotheses and revising or confirming the theory

a paradigm based on the idea that social context and interaction frame our realities

when a researcher starts with a set of observations and then moves from particular experiences to a more general set of propositions about those experiences

Part of the qualitative data analysis process where we begin to interpret and assign meaning to the data.

An initial phase of coding that involves reviewing the data to determine the preliminary ideas that seem important and potential labels that reflect their significance.

Axial coding is phase of qualitative analysis in which the research will revisit the open codes and identify connections between codes, thereby beginning to group codes that share a relationship.

Selective or theoretical coding is part of a qualitative analysis process that seeks to determine how important concepts and their relationships to each other come together, providing a theory that describes the focus of the study. It often results in an overarching or unifying idea tying these concepts together.

Constant comparison reflects the motion that takes place in some qualitative analysis approaches whereby the researcher moves back and forth between the data and the emerging categories and evolving understanding they have in their results. They are continually checking what they believed to be the results against the raw data they are working with.

Trustworthiness is a quality reflected by qualitative research that is conducted in a credible way; a way that should produce confidence in its findings.

claims about the world that appear scientific but are incompatible with the values and practices of science