18.3 Preparations: Creating a plan for qualitative data analysis Learning Objectives

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Identify how your research question, research aim, sample selection, and type of data may influence your choice of analytic methods

- Outline the steps you will take in preparation for conducting qualitative data analysis in your proposal

Now we can turn our attention to planning your analysis. The analysis should be anchored in the purpose of your study. Qualitative research can serve a range of purposes. Below is a brief list of general purposes we might consider when using a qualitative approach.

- Are you trying to understand how a particular group is affected by an issue?

- Are you trying to uncover how people arrive at a decision in a given situation?

- Are you trying to examine different points of view on the impact of a recent event?

- Are you trying to summarize how people understand or make sense of a condition?

- Are you trying to describe the needs of your target population?

If you don’t see the general aim of your research question reflected in one of these areas, don’t fret! This is only a small sampling of what you might be trying to accomplish with your qualitative study. Whatever your aim, you need to have a plan for what you will do once you have collected your data.

Exercises

Decision Point: What are you trying to accomplish with your data?

- Consider your research question. What do you need to do with the qualitative data you are gathering to help answer that question?

To help answer this question, consider:

-

- What action verb(s) can be associated with your project and the qualitative data you are collecting? Does your research aim to summarize, compare, describe, examine, outline, identify, review, compose, develop, illustrate, etc.?

- Then, consider noun(s) you need to pair with your verb(s)—perceptions, experiences, thoughts, reactions, descriptions, understanding, processes, feelings, actions responses, etc.

Iterative or linear

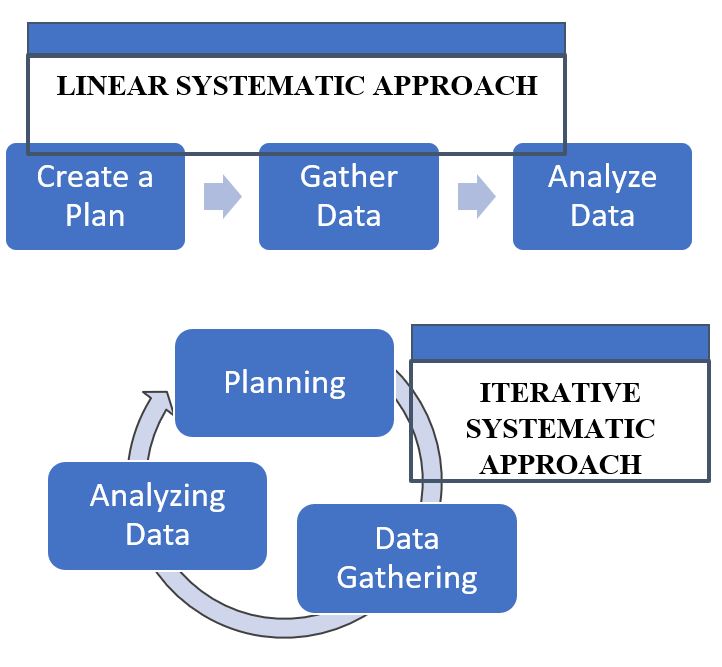

We touched on this briefly in Chapter 17 about qualitative sampling, but this is an important distinction to consider. Some qualitative research is linear, meaning it follows more of a traditionally quantitative process: create a plan, gather data, and analyze data; each step is completed before we proceed to the next. You can think of this like how information is presented in this book. We discuss each topic, one after another.

However, many times qualitative research is iterative, or evolving in cycles. An iterative approach means that once we begin collecting data, we also begin analyzing data as it is coming in. This early and ongoing analysis of our (incomplete) data then impacts our continued planning, data gathering and future analysis. Again, coming back to this book, while it may be written linear, we hope that you engage with it iteratively as you are building your proposal. By this we mean that you will revisit previous sections so you can understand how they fit together and you are in continuous process of building and revising how you think about the concepts you are learning about.

As you may have guessed, there are benefits and challenges to both linear and iterative approaches. A linear approach is much more straightforward, each step being fairly defined. However, linear research being more defined and rigid also presents certain challenges. A linear approach assumes that we know what we need to ask or look for at the very beginning of data collection, which often is not the case.

With iterative research, we have more flexibility to adapt our approach as we learn new things. We still need to keep our approach systematic and organized, however, so that our work doesn’t become a free-for-all. As we adapt, we do not want to stray too far from the original premise of our study. It’s also important to remember with an iterative approach that we may risk ethical concerns if our work extends beyond the original boundaries of our informed consent and IRB agreement. If you feel that you do need to modify your original research plan in a significant way as you learn more about the topic, you can submit an addendum to modify your original application that was submitted. Make sure to keep detailed notes of the decisions that you are making and what is informing these choices. This helps to support transparency and your credibility throughout the research process.

Exercises

Decision Point: Will your analysis reflect more of a linear or an iterative approach?

- What justifies or supports this decision?

Think about:

- Fit with your research question

- Available time and resources

- Your knowledge and understanding of the research process

Exercises

Reflexive Journal Entry Prompt

- Are you more of a linear thinker or an iterative thinker?

- What evidence are you basing this on?

- How might this help or hinder your qualitative research process?

- How might this help or hinder you in a practice setting as you work with clients?

Acquainting yourself with your data

As you begin your analysis, you need to get to know your data. This usually means reading through your data prior to any attempt at breaking it apart and labeling it. You might read through a couple of times, in fact. This helps give you a more comprehensive feel for each piece of data and the data as a whole, again, before you start to break it down into smaller units or deconstruct it. This is especially important if others assisted us in the data collection process. We often gather data as part of team and everyone involved in the analysis needs to be very familiar with all of the data.

Capturing your reaction to the data

During the review process, our understanding of the data often evolves as we observe patterns and trends. It is a good practice to document your reaction and evolving understanding. Your reaction can include noting phrases or ideas that surprise you, similarities or distinct differences in responses, additional questions that the data brings to mind, among other things. We often record these reactions directly in the text or artifact if we have the ability to do so, such as making a comment in a word document associated with a highlighted phrase. If this isn’t possible, you will want to have a way to track what specific spot(s) in your data your reactions are referring to. In qualitative research we refer to this process as memoing. Memoing is a strategy that helps us to link our findings to our raw data, demonstrating transparency. If you are using a Computre-Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS) software package, memoing functions are generally built into the technology.

Capturing your emerging understanding of the data

During your reviewing and memoing you will start to develop and evolve your understanding of what the data means. This understanding should be dynamic and flexible, but you want to have a way to capture this understanding as it evolves. You may include this as part of your memoing or as part of your codebook where you are tracking the main ideas that are emerging and what they mean. Figure 18.3 is an example of how your thinking might change about a code and how you can go about capturing it. Coding is a part of the qualitative data analysis process where we begin to interpret and assign meaning to the data. It represents one of the first steps as we begin to filter the data through our own subjective lens as the researcher. We will discuss coding in much more detail in the sections below covering various different approaches to analysis.

| Date | Code Lable | Explanations |

| 6/18/18 | Experience of wellness | This code captures the different ways people describe wellness in their lives |

| 6/22/18 | Understanding of wellness | Changed the label of this code slightly to reflect that many participants emphasize the cognitive aspect of how they understand wellness—how they think about it in their lives, not only the act of ‘experiencing it’. This understanding seems like a precursor to experiencing. An evolving sense of how you think about wellness in your life. |

| 6/25/18 | Wellness experienced by developing personal awareness | A broader understanding of this category is developing. It involves building a personalized understanding of what makes up wellness in each person’s life and the role that they play in maintaining it. Participants have emphasized that this is a dynamic, personal and onging process of uncovering their own intimate understanding of wellness. They describe having to experiment, explore, and reflect to develop this awareness. |

Exercises

Decision Point: How to capture your thoughts?

- How will you capture your thinking about the data and your emerging understanding about what it means?

- What will this look like?

- How often will you do it?

- How will you keep it organized and consistent over time?

In addition, you will want to be actively using your reflexive journal during this time. Document your thoughts and feelings throughout the research process. This will promote transparency and help account for your role in the analysis.

For entries during your analysis, respond to questions such as these in your journal:

- What surprises you about what participants are sharing?

- How has this information challenged you to look at this topic differently?

- As you reflect on these findings, what personal biases or preconceived notions have been exposed for you?

- Where might these have come from?

- How might these be influencing your study?

- How will you proceed differently based on what you are learning?

By including community members as active co-researchers, they can be invaluable in reviewing, reacting to and leading the interpretation of data during your analysis. While it can certainly be challenging to converge on an agreed-upon version of the results; their insider knowledge and lived experience can provide very important insights into the data analysis process.

Determining when you are finished

When conducting quantitative research, it is perhaps easier to decide when we are finished with our analysis. We determine the tests we need to run, we perform them, we interpret them, and for the most part, we call it a day. It’s a bit more nebulous for qualitative research. There is no hard and fast rule for when we have completed our qualitative analysis. Rather, our decision to end the analysis should be guided by reflection and consideration of a number of important questions. These questions are presented below to help ensure that your analysis results in a finished product that is comprehensive, systematic, and coherent.

Have I answered my research question?

Your analysis should be clearly connected to and in service of answering your research question. Your examination of the data should help you arrive at findings that sufficiently address the question that you set out to answer. You might find that it is surprisingly easy to get distracted while reviewing all your data. Make sure as you conducted the analysis you keep coming back to your research question.

Have I utilized all my data?

Unless you have intentionally made the decision that certain portions of your data are not relevant for your study, make sure that you don’t have sources or segments of data that aren’t incorporated into your analysis. Just because some data doesn’t “fit” the general trends you are uncovering, find a way to acknowledge this in your findings as well so that these voices don’t get lost in your data.

Have I fulfilled my obligation to my participants?

As a qualitative researcher, you are a craftsperson. You are taking raw materials (e.g. people’s words, observations, photos) and bringing them together to form a new creation, your findings. These findings need to both honor the original integrity of the data that is shared with you, but also help tell a broader story that answers your research question(s).

Have I fulfilled my obligation to my audience?

Not only do your findings need to help answer your research question, but they need to do so in a way that is consumable for your audience. From an analysis standpoint, this means that we need to make sufficient efforts to condense our data. For example, if you are conducting a thematic analysis, you don’t want to wind up with 20 themes. Having this many themes suggests that you aren’t finished looking at how these ideas relate to each other and might be combined into broader themes. Having these sufficiently reduced to a handful of themes will help tell a more complete story, one that is also much more approachable and meaningful for your reader.

In the following subsections, there is information regarding a variety of different approaches to qualitative analysis. In designing your qualitative study, you would identify an analytical approach as you plan out your project. The one you select would depend on the type of data you have and what you want to accomplish with it.

Key Takeaways

- Qualitative research analysis requires preparation and careful planning. You will need to take time to familiarize yourself with the data in general sense before you begin analyzing.

- Once you begin your analysis, make sure that you have strategies for capture and recording both your reaction to the data and your corresponding developing understanding of what the collective meaning of the data is (your results). Qualitative research is not only invested in the end results but also the process at which you arrive at them.

Exercises

Decision Point: When will you stop?

- How will you know when you are finished? What will determine your endpoint?

- How will you monitor your work so you know when it’s over?

A research process where you create a plan, you gather your data, you analyze your data and each step is completed before you proceed to the next.

An iterative approach means that after planning and once we begin collecting data, we begin analyzing as data as it is coming in. This early analysis of our (incomplete) data, then impacts our planning, ongoing data gathering and future analysis as it progresses.

The point where gathering more data doesn't offer any new ideas or perspectives on the issue you are studying. Reaching saturation is an indication that we can stop qualitative data collection.

Memoing is the act of recording your thoughts, reactions, quandaries as you are reviewing the data you are gathering.

These are software tools that can aid qualitative researchers in managing, organizing and manipulating/analyzing their data.

A document that we use to keep track of and define the codes that we have identified (or are using) in our qualitative data analysis.

Part of the qualitative data analysis process where we begin to interpret and assign meaning to the data.

A research journal that helps the researcher to reflect on and consider their thoughts and reactions to the research process and how it may be shaping the study