11.1 The sampling process

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Explain the difference between unit of observation and unit of analysis

- Describe the process of sampling

- Define setting, target population, study population, sampling frame

- Explain the difference between a hypothetical sampling frame and a physical sampling frame

Pre-Awareness Check (Environment)

Considering what you know of your target population, where would your target population be the most accessible? What organizations, programs, entities should you target to promote your study within the population?

Who is your study about and who should you talk to?

Let’s consider a common issue in social work research: the implementation and impact of a social work intervention. Who has first-hand knowledge and who has second-hand knowledge? Well, practitioners would have first-hand knowledge about implementing the intervention. For example, they might discuss with you the unique language they use to help clients understand the intervention. They would have second-hand knowledge of the experiences of the clients in the intervention. Clients, on the other hand, have first-hand knowledge about the impact of those interventions on their lives.

Our goal in this chapter is to help you understand how to find the people or things you need to study in order to answer a research question. It may be helpful at this point to distinguish between two concepts. Your unit of analysis is the entity that you wish to be able to say something about at the end of your study (probably what you’d consider to be the main focus of your study). Your unit of observation is the entity (or entities) that you actually observe, measure, or collect in the course of trying to learn something about your unit of analysis.

Your unit of analysis will be determined by your research question. Your unit of observation, on the other hand, is determined largely by the method of data collection you use to answer that research question.

It is often the case that your unit of analysis and unit of observation are the same. For example, we may want to say something about social work students (unit of analysis), so we ask social work students at our university to complete a survey (unit of observation) for our study. In this case, we are observing individuals, i.e. students, so we can make conclusions about individuals.

On the other hand, our unit of analysis and observation can differ. We could sample social work students to draw conclusions about organizations or universities. Perhaps we are comparing historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) and primarily white institutions (PWIs). Even though our sample was made up of individual students from various universities (our unit of observation), our unit of analysis was the university as an organization. Conclusions we made from individual-level data were used to understand larger organizations.

Similarly, we could adjust our sampling approach to target specific student cohorts. Perhaps we wanted to understand the experiences of Black social work students in PWIs. We could choose an individual unit of observation by selecting students, or a group unit of observation by studying the National Association of Black Social Workers on campus.

Sometimes the units of analysis and observation differ due to pragmatic reasons. If we wanted to study whether being a social work student impacted family relationships, we may choose to observe students in social work programs who could give us information about how they behaved in the home. This would be more feasible than trying to include family members in the study. In this case, we would be observing students to draw conclusions about families.

In sum, there are many potential units of analysis that a social worker might examine, but some of the most common include individuals, groups, and organizations. Click on each of the dropdown arrows in Table 11.1 to read examples that identify the units of observation and analysis in a hypothetical study of student addiction to electronic gadgets.

Table 11.1 Research questions, data collection, units of observation, and hypothetical statement of findings by unit of analysis

Population: Who do you want to study?

In social scientific research, a target population is the entirety of people, policies, organizations, etc. you are most interested in. It is often the “who” that you want to be able to generalize about at the end of your study. While populations in research may be rather large, such as “people living in the United States” they are typically more specific than that. For example, a study will likely specify which people, such as “adults over the age of 18” or “people with developmental disabilities” or “students in a social work program.”

It is almost impossible for a researcher to gather data from their entire population of interest. This might sound surprising or disappointing until you think about the kinds of research questions that social workers typically ask. For example, let’s say we wish to answer the following question: “How does gender relate to attendance in a program for perpetrators of intimate partner violence (IPV)?” Would you expect to be able to collect data from all people in perpetrator of IPV intervention programs across all nations from all historical time periods? Unless you plan to make answering this research question your entire life’s work (and then some), I’m guessing your answer is a resounding no. But that doesn’t mean you can’t conduct research about the target population. While you can’t gather data from everyone, you can find some elements from your target population to study.

Exercises

TRACK 1 (IF YOU ARE CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

Let’s think about who could possibly be in your study.

- What is your population, the people you want to make conclusions about?

- Do your unit of analysis and unit of observation differ or are they the same?

- Can you ethically and practically get first-hand information from the people most knowledgeable about the topic, or will you rely on second-hand information from less vulnerable populations?

TRACK 2 (IF YOU AREN’T CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

Imagine you are studying the disproportionate rates of abuse and sexual assault for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. You are interested in learning more about abuse prevention strategies, such as healthy relationship education, for this population.

- What is the population, the people you want to make conclusions about?

- Would your unit of analysis and unit of observation differ or would they be the same?

- Can you ethically and practically get first-hand information from the people most knowledgeable about the topic, or will you rely on second-hand information from less vulnerable populations?

Setting: Where will you go to find elements of your population?

You will need to figure out where to go to get data. Social work researchers must think about locations or groups in which your target population gathers or interacts. We can use these settings to access potential research participants of the target population. However, most settings (e.g., agency, social media, household landline telephones) have access to only a segment of the target population.

The entire group of elements from the population that you have access to for your study is called the study population. You may ultimately be interested in the population of all older adults living in nursing homes, but for your study, the study population may be older adults living in nursing homes in your town.

We can use the setting(s) that contain our study population to gather a list of potential participants. A sampling frame is just such a list of elements from which you will draw your sample. But where do you find a sampling frame? Answering this question is the first step in gathering a sample for your study.

In a study on quality of care in nursing homes may choose a local nursing home because it’s easy to access. The sampling frame could be a census of all of the residents of the nursing home. You would select your participants for your study from the list of residents. Note that this is a real list. That is, an administrator at the nursing home could give you a list with every resident’s name or ID number from which you would select your participants. If you decided to include more nursing homes in your study, then your sampling frame could be all the residents at all the nursing homes who agreed to participate in your study.

Let’s consider some more examples. Unlike nursing home patients, cancer survivors do not usually live in an bounded location and may no longer receive treatment at a hospital or clinic. For social work researchers to reach participants, they may consider partnering with a support group that serves this population. Perhaps there is a support group at a local church that survivors may attend. Without a set list of people, your sampling frame might simply be the people who show up to the support group on the nights you were there. Similarly, if you posted an advertisement in an online peer-support group for people with cancer, your sampling frame is the people who view the site. In these cases, you don’t have a physical list, but there is still a sampling frame. Another example might include using a flyer to let people know about your study, in which case your sampling frame would be anyone who walks past your flyer wherever you hang it—usually in a strategic location where you know your population will be.

To reiterate, sampling frames can be a real or hypothetical lists of elements from the study population. Having a real list allows you to clearly identify who is in your study and define what chance they will have of being selected for the study. However, hypothetical lists do not allow you to be so specific.

It is important to remember that accessing your sampling frame must be practical and ethical, as we discussed in Chapter 2 and Chapter 6. For studies that present risks to participants, approval from gatekeepers and the university’s institutional review board (IRB) is needed.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Your sampling frame is generally not just everyone in the setting you identified. For example, if you were studying MSW students who are first-generation college students, you might select your university as the setting, but not everyone in the MSW program is a first-generation student. You need to be more specific about which characteristics or attributes individuals either must have or cannot have to participate in the study.

Inclusion criteria are the characteristics a person must possess in order to be included in your sample. If you were conducting a survey on LGBTQ2S+ discrimination at your agency, you might want to sample only clients who identify as LGBTQ2S+. In that case, your inclusion criteria for your sample would be that individuals have to identify as LGBTQ2S+.

Comparably, exclusion criteria are characteristics that disqualify a person from being included in your sample. In the previous example, you could think of cis-gender and heterosexual as an exclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria are often the mirror image of inclusion criteria. However, there may be other criteria by which we want to exclude people from our sample. For example, we may exclude clients who were recently discharged or those who have just begun to receive services.

Exercises

TRACK 1 (IF YOU ARE CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

- Before you start, what do you know about your setting and potential participants?

- Are there likely to be enough people in the setting of your study who meet the inclusion criteria?

You want to avoid throwing out half of the surveys you get back because the respondents aren’t a part of your target population. This is a common error I see in student proposals.

TRACK 2 (IF YOU AREN’T CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

Imagine you are studying the disproportionate rates of abuse and sexual assault for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. You are interested in learning more about abuse prevention strategies, such as healthy relationship education, for this population.

- What do you know about your setting and potential participants?

- Are there likely to be enough people in the setting of your study who meet the inclusion criteria?

Recruitment: How will you ask people to participate in your study?

Once you have a setting, sampling frame (either physical or hypothetical), and your inclusion/exclusion criteria, all that is left is to connect with potential participants. Recruitment refers to the process by which researchers inform potential participants about the study and ask them to participate in the research project. Recruitment comes in many different forms. If you have ever received a phone call asking for you to participate in a survey, someone has attempted to recruit you for a study. Perhaps you’ve seen print advertisements on buses, in student centers, or on social media. We will learn more about specific types of sampling. For now, the important thing to remember is that it is important to make sure your recruitment makes sense with your sampling strategy.

Recruitment is the first time in which you will contact potential study participants. Before you start this process, you must have approval from your university’s institutional review board (IRB) as well as any gatekeepers at the locations in which you plan to conduct your study. In many situations, gatekeepers will be necessary to gain access to your participants. For example, a gatekeeper can forward your recruitment email across their employee email list.

Recruitment can take many forms. You may show up at meetings and gatherings to ask for study volunteers. You may send emails or letters. You may advertise across a variety of media types. Each step of the recruitment process should be vetted and approved by the IRB as well as other stakeholders and gatekeepers. You will need to set reasonable expectations for how many reminders you will send to a person before moving on. Generally, it is a good idea to give people a little while to respond, though reminders are often accompanied by an increase in participation. Pragmatically, it is a good idea for you to think through each step of the recruitment process and how much time it will take to complete it.

The goal of recruitment is to enroll participants into the study. This entails providing participants with the informed consent information you prepared and the IRB approved. It is imperative to review consent information with human participants before completing any other research activities Only when the participant is totally clear on the purpose, risks and benefits, confidentiality protections, and other information detailed in Chapter 3, can you ethically move forward with including them in your sample.

Sample: Who actually participates in your study?

Once you have a sampling frame and decide which characteristics you will include and exclude, you employ a sampling strategy (which we will cover in Section 11.2), and you’re left with the group of elements for your study, your sample.

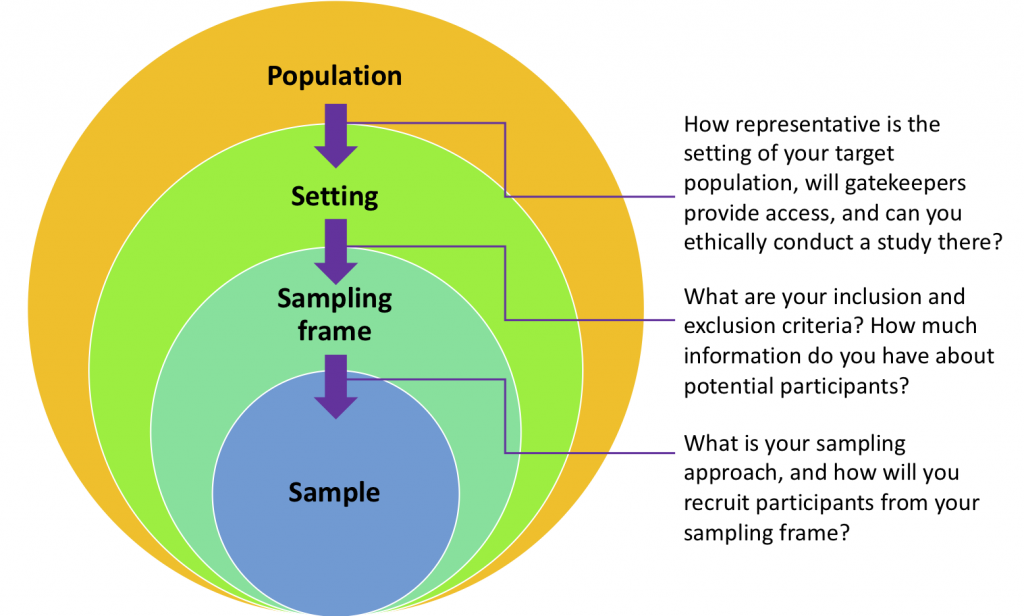

Visualizing sampling terms

Sampling terms can be a bit daunting at first. However, with some practice, they will become second nature. Let’s walk through an example Matt DeCarlo (2018)[1] shares from one of his research projects. Matt collected data related to how much it costs to become a licensed clinical social worker (LCSW) in each state. Follow along with Figure 11.1 as a guide.

Matt’s unit of analysis is states in the United States, but his unit of observations is clinical social workers, so this will be his target population as these are the people from whom he will draw his conclusions. The next step inward would be to find a setting from which to get his sampling frame. Unfortunately, there is no list of every licensed clinical social worker in the United States. He could write to each state’s social work licensing board and ask for a list of names and addresses, perhaps even using a Freedom of Information Act request if they were unwilling to share the information. That option sounds time-consuming and may have a low likelihood of success. Instead, he tried to figure out a convenient setting where social workers are likely to congregate. He considered setting up a booth at a National Association of Social Workers (NASW) conference and asking people to participate in his survey. Ultimately, this would prove too costly, and the people who gather at an NASW conference may not be representative of the general population of clinical social workers. He finally discovered the NASW membership email list, which is available to advertisers, including researchers advertising for research projects. While the NASW list does not contain every clinical social worker, it reaches over one hundred thousand social workers regularly through its monthly e-newsletter, a large proportion of social workers in practice, so he felt the setting was likely to draw a representative sample. To gain access to this setting from gatekeepers, he had to provide paperwork showing his study had undergone IRB review and submit his measures for approval by the mailing list administrator.

Once he gained access from gatekeepers, his setting became the NASW and his sampling frame was the NASW membership list. He decided to recruit 5,000 participants because he knew that people sometimes do not read or respond to email advertisements, and he figured maybe 20% would respond, which would give him around 1,000 responses.

However, figuring out this number to recruit was a challenge, because he had to balance the costs associated with using the NASW mailing list. As you can see on their pricing page, it would cost money to learn personal information about his potential participants, which he would need to check later in order to determine how representative his sample was of the overall population of clinical social workers. For example, he could see if his sample was comparable in race, age, gender, or state of residence to the broader population of social workers by comparing his sample with information about all social workers published by NASW. He presented his recruitment options to his external funder as:

- He could send an email advertisement to a lot of people (5,000), but he would know very little about them and they would get only one advertisement.

- He could send multiple advertisements to fewer people (1,000) reminding them to participate, but he would also know more about them by purchasing access to personal information.

- He could send multiple advertisements to fewer people (2,500), but not purchase access to personal information to minimize costs.

Matt and his funders decided to go with option #1. When he sent his email recruiting participants for the study, he specified that he only wanted to hear from social workers who were either currently receiving or recently received clinical supervision for licensure—his inclusion criteria. This was important because many of the people on the NASW membership list may not be licensed or license-seeking social workers. So, his sampling frame was the email addresses on the NASW mailing list who fit the inclusion criteria for the study, which he figured would be at least a few thousand people. Unfortunately, only 150 licensed or license-seeking clinical social workers responded to his recruitment email and completed the survey. You will learn in Section 11.3 why this did not make for a very good sample.

From this example, you can see that sampling is a process. The process flows sequentially from figuring out your target population, to thinking about where to find people from your target population, to figuring out how much information you know about potential participants, and finally to selecting recruiting people from that list to be a part of your sample. Through the sampling process, you must consider where people in your target population are likely to be and how best to get their attention for your study. Sampling can be an easy process, like calling every 100th name from the phone book, or challenging, like standing every day for a few weeks in an area in which people experiencing homelessness gather for shelter. In either case, your goal is to recruit enough people who will participate in your study and can represent your population well.

Sampling objects

Many research projects do not involve recruiting and sampling human subjects. Instead, they sample objects like client charts, movies, or books. The same terms apply, but the process may be bit easier if the research is not human subjects research. When we are sampling documents, we need to identify which documents are relevant. It is important to create exclusion and inclusion criteria based on your research question. Once you have a suitable sampling frame of documents eligible for inclusion in your study, you employ your sampling strategy to select the files to analyze. For example, if a research project involves analyzing client files, it is unlikely you will look at every client file that your agency has. You will need to figure out which client files are important to your research question. Perhaps you want to sample clients who have a diagnosis of reactive attachment disorder. You would have to create a list (sampling frame) of all clients at your agency (setting) who have reactive attachment disorder (your inclusion criteria) then use your sampling approach (which we will discuss in the next sections) to select which client files you will actually analyze for your study (your sample).

Sampling documents may also need consent and buy-in from stakeholders and gatekeepers. Assuming you have approval to conduct your study and access to the documents you need, the process of recruitment is much easier than in studies sampling humans. There may be no informed consent process when sampling documents, though research with confidential health or education records must be done in accordance with privacy laws such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act. The IRB can help you determine what types of approval and consent you may need for research with documents. Barring any technical or policy obstacles, the gathering of documents may be easier and less time consuming than sampling humans.

Choosing a sample from the sampling frame

The last step in sampling is choosing a sample from the sampling frame using a well-defined sampling technique. Sampling techniques can be grouped into two broad categories: probability (random) sampling and non-probability sampling. Probability sampling is ideal if generalizability of results is important for your study, but there may be unique circumstances where non-probability sampling can also be justified. These techniques are discussed in the next two sections.

Test your knowledge

In this section, we have reviewed the sampling process. In the next section, 11.2, we will review non-probability sampling, which includes sampling approaches that tend to involve hypothetical sampling frames rather than physical list sampling frames. Use the interactive tools below to test your knowledge on the information in this section.

Key Takeaways

- Think about virtual or in-person settings in which your target population gathers. Remember that you may have to engage gatekeepers and stakeholders in accessing many settings, and that you will need to assess the pragmatic challenges and ethical risks and benefits of your study.

- Consider whether you can sample documents like agency files to answer your research question. Documents are much easier to “recruit” than people!

- Researchers must consider which characteristics are necessary for people to have (inclusion criteria) or not have (exclusion criteria), as well as how to recruit participants into the sample.

- Social workers can sample individuals, groups, or organizations.

- Sometimes the unit of analysis and the unit of observation in the study differ. This is often true as target populations may be too vulnerable to expose to research whose potential harms may outweigh the benefits.

- One’s recruitment method has to match one’s sampling approach, as will be explained in the next chapter.

Exercises

TRACK 1 (IF YOU ARE CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

Once you have identified who may be a part of your study, the next step is to think about where those people gather. Are there in-person locations in your community or on the internet that are easily accessible. List at least one potential setting for your project. Describe for each potential setting:

- Based on what you know right now, how representative of your population are potential participants in the setting?

- How much information can you reasonably know about potential participants before you recruit them?

- Are there gatekeepers and what kinds of concerns might they have?

- Are there any stakeholders that may be beneficial to bring on board as part of your research team for the project?

- What interests might stakeholders and gatekeepers bring to the project and would they align with your vision for the project?

- What ethical issues might you encounter if you sampled people in this setting.

Even though you may not be 100% sure about your setting yet, let’s think about the next steps.

- For the settings you’ve identified, how might you recruit participants?

- Identify your inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria, and assess whether you have enough information on whether people in each setting will meet them.

TRACK 2 (IF YOU AREN’T CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

Imagine you are studying the disproportionate rates of abuse and sexual assault for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. You are interested in learning more about abuse prevention strategies, such as healthy relationship education, for this population.

The next step is to think about where this population might gather. Are there in-person locations in your community or on the internet that are easily accessible? List at least one potential setting for your project. Describe for each potential setting:

- How representative of your population are potential participants in the setting?

- How much information can you reasonably know about potential participants before you recruit them?

- Are there gatekeepers and what kinds of concerns might they have?

- Are there any stakeholders that may be beneficial to bring on board as part of your research team for the project?

- What interests might stakeholders and gatekeepers bring to the project and would they align with your vision for the project?

- What ethical issues might you encounter if you sampled people in this setting.

After brainstorming some ideas about your setting, think about the next steps.

- For the settings you’ve identified, how might you recruit participants?

- Identify your inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria, and assess whether you have enough information on whether people in each setting will meet them.

- DeCarlo, M. (2018). Scientific inquiry in social work research. https://scientificinquiryinsocialwork.pressbooks.com/ ↵

entity that a researcher wants to say something about at the end of her study (individual, group, or organization)

the entities that a researcher actually observes, measures, or collects in the course of trying to learn something about her unit of analysis (individuals, groups, or organizations)

the larger group of people you want to be able to make conclusions about based on the conclusions you draw from the people in your sample

individual units of a population

the subset of the target population available for study

the list of people from which a researcher will draw her sample

the people or organizations who control access to the population you want to study

an administrative body established to protect the rights and welfare of human research subjects recruited to participate in research activities conducted under the auspices of the institution with which it is affiliated

Inclusion criteria are general requirements a person must possess to be a part of your sample.

characteristics that disqualify a person from being included in a sample

the process by which the researcher informs potential participants about the study and attempts to get them to participate

the group of people you successfully recruit from your sampling frame to participate in your study