14.2 True experiments

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Describe a true experimental design in social work research

- Understand the different types of true experimental designs

- Determine what kinds of research questions true experimental designs are suited for

- Discuss advantages and disadvantages of true experimental designs

A true experiment, often considered to be the “gold standard” in research designs, is thought of as one of the most rigorous of all research designs. In this design, one or more independent variables (as treatments) are manipulated by the researcher, subjects are randomly assigned (i.e., random assignment) to different treatment levels, and the results of the treatments on outcomes (dependent variables) are observed. The unique strength of experimental research is its ability to increase internal validity and help establish causality through treatment manipulation, while controlling for the effects of extraneous variables. As such they are best suited for explanatory research questions.

In true experimental design, research subjects are assigned to either an experimental group, which receives the treatment or intervention being investigated, or a control group, which does not. Control groups may receive no treatment at all, the standard treatment (which is called “treatment as usual” or TAU), or a treatment that entails some type of contact or interaction without the characteristics of the intervention being investigated. For example, the control group may participate in a support group while the experimental group is receiving a new group-based therapeutic intervention consisting of education and cognitive behavioral group therapy.

After determining the nature of the experimental and control groups, the next decision a researcher must make is when they need to collect data during their experiment. Do they take a baseline measurement and then a measurement after treatment, or just a measurement after treatment, or do they handle data collection another way? Below, we’ll discuss three main types of true experimental designs. There are sub-types of each of these designs, but here, we just want to get you started with some of the basics.

Using a true experiment in social work research is often difficult and can be quite resource intensive. True experiments work best with relatively large sample sizes, and random assignment, a key criterion for a true experimental design, is hard (and unethical) to execute in practice when you have people in dire need of an intervention. Nonetheless, some of the strongest evidence bases are built on true experiments.

For the purposes of this section, let’s bring back the example of CBT for the treatment of social anxiety. We have a group of 500 individuals who have agreed to participate in our study, and we have randomly assigned them to the control and experimental groups. The participants in the experimental group will receive CBT, while the participants in the control group will receive a series of videos about social anxiety.

Classical experiments (pretest posttest control group design)

The elements of a classical experiment are (1) random assignment of participants into an experimental and control group, (2) a pretest to assess the outcome(s) of interest for each group, (3) delivery of an intervention/treatment to the experimental group, and (4) a posttest to both groups to assess potential change in the outcome(s).

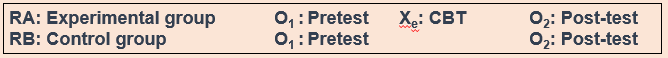

When explaining experimental research designs, we often use diagrams with abbreviations to visually represent the components of the experiment. Table 14.2 starts us off by laying out what the abbreviations mean.

| R | Random assignment |

| O | Observation (assessment of the dependent/outcome variable) |

| X | Intervention or treatment |

| Xe | Experimental condition (i.e., the treatment or intervention) |

| Xi | Treatment as usual (sometimes denoted TAU) |

| A, B, C, etc. | Denotes different groups (control/comparison and experimental) |

Figure 14.1 depicts a classical experiment using our example of assessing the intervention of CBT for social anxiety. In the figure, RA denotes random assignment to the experimental group A and RB is random assignment to the control group B. O1 (observation 1) denotes the pretest, Xe denotes the experimental intervention, and O2 (observation 2) denotes the posttest.

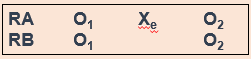

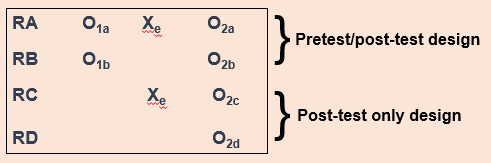

The more general, or universal, notation for classical experimental design is shown in Figure 14.2.

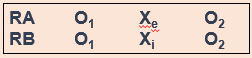

In a situation where the control group received treatment as usual instead of no intervention, the diagram would look this way (Figure 14.3), with Xi denoting treatment as usual:

Hopefully, these diagrams provide you a visualization of how this type of experiment establishes temporality, a key component of a causal relationship. By administering the pretest, researchers can assess if the change in the outcome occured after the intervention. Assuming there is a change in the scores between the pretest and posttest, we would be able to say that yes, the change did occur after the intervention.

Posttest only control group design

Posttest only control group design involves only giving participants a posttest, just like it sounds. But why would you use this design instead of using a pretest posttest design? One reason could be to avoid potential testing effects that can happen when research participants take a pretest.

In research, the testing effect threatens internal validity when the pretest changes the way the participants respond on the posttest or subsequent assessments (Flannelly, Flannelly, & Jankowski, 2018).[1] A common example occurs when testing interventions for cognitive impairment in older adults. By taking a cognitive assessment during the pretest, participants get exposed to the items on the assessment and get to “practice” taking it (see for example, Cooley et al., 2015).[2] They may perform better the second time they take it because they have learned how to take the test, not because there have been changes in cognition. This specific type of testing effect is called the practice effect.[3]

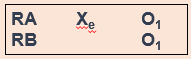

The testing effect isn’t always bad in practice—our initial assessments might help clients identify or put into words feelings or experiences they are having when they haven’t been able to do that before. In research, however, we might want to control its effects to isolate a cleaner causal relationship between intervention and outcome. Going back to our CBT for social anxiety example, we might be concerned that participants would learn about social anxiety symptoms by virtue of taking a pretest. They might then identify that they have those symptoms on the posttest, even though they are not new symptoms for them. That could make our intervention look less effective than it actually is. To mitigate the influence of testing effects, posttest only control group designs do not administer a pretest to participants. Figure 14.4 depicts this.

A drawback to the posttest only control group design is that without a baseline measurement, establishing causality can be more difficult. If we don’t know someone’s state of mind before our intervention, how do we know our intervention did anything at all? Establishing time order is thus a little more difficult. The posttest only control group design relies on the random assignment to groups to create groups that are equivalent at baseline because, without a pretest, researchers cannot assess whether the groups are equivalent before the intervention. Researchers must balance this consideration with the benefits of this type of design.

Solomon four group design

One way we can possibly measure how much the testing effect threatens internal validity is with the Solomon four group design. Basically, as part of this experiment, there are two experimental groups and two control groups. The first pair of experimental/control groups receives both a pretest and a posttest. The other pair receives only a posttest (Figure 14.5). In addition to addressing testing effects, this design also addresses the problems of establishing time order and equivalent groups in posttest only control group designs.

For our CBT project, we would randomly assign people to four different groups instead of just two. Groups A and B would take our pretest measures and our posttest measures, and groups C and D would take only our posttest measures. We could then compare the results among these groups and see if they’re significantly different between the folks in A and B, and C and D. If they are, we may have identified some kind of testing effect, which enables us to put our results into full context. We don’t want to draw a strong causal conclusion about our intervention when we have major concerns about testing effects without trying to determine the extent of those effects.

Solomon four group designs are less common in social work research, primarily because of the logistics and resource needs involved. Nonetheless, this is an important experimental design to consider when we want to address major concerns about testing effects.

Key Takeaways

- True experimental design is best suited for explanatory research questions.

- True experiments require random assignment of participants to control and experimental groups.

- Pretest posttest research design involves two points of measurement—one pre-intervention and one post-intervention.

- Posttest only research design involves only one point of measurement—after the intervention or treatment. It is a useful design to minimize the effect of testing effects on our results.

- Solomon four group research design involves both of the above types of designs, using 2 pairs of control and experimental groups. One group receives both a pretest and a posttest, while the other receives only a posttest. This can help uncover the influence of testing effects.

Exercises

TRACK 1 (IF YOU ARE CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

- Think about a true experiment you might conduct for your research project. Which design would be best for your research, and why?

- What challenges or limitations might make it unrealistic (or at least very complicated!) for you to carry your true experimental design in the real-world as a researcher?

- What hypothesis(es) would you test using this true experiment?

TRACK 2 (IF YOU AREN’T CREATING A RESEARCH PROPOSAL FOR THIS CLASS):

Imagine you are interested in studying child welfare practice. You are interested in learning more about community-based programs aimed to prevent child maltreatment and to prevent out-of-home placement for children.

- Think about a true experiment you might conduct for this research project. Which design would be best for this research, and why?

- What challenges or limitations might make it unrealistic (or at least very complicated) for you to carry your true experimental design in the real-world as a researcher?

- What hypothesis(es) would you test using this true experiment?

- Flannelly, K. J., Flannelly, L. T., & Jankowski, K. R. B. (2018). Threats to the internal validity of experimental and quasi-experimental research in healthcare. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 24(3), 107-130. https://doi.org/10.1080/08854726.2017.1421019 ↵

- Cooley, S. A., Heaps, J. M., Bolzenius, J. D., Salminen, L. E., Baker, L. M., Scott, S. E., & Paul, R. H. (2015). Longitudinal change in performance on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment in older adults. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 29(6), 824-835. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2015.1087596 ↵

- Duff, K., Beglinger, L. J., Schultz, S. K., Moser, D. J., McCaffrey, R. J., Haase, R. F., Westervelt, H. J., Langbehn, D. R., Paulsen, J. S., & Huntington's Study Group (2007). Practice effects in the prediction of long-term cognitive outcome in three patient samples: a novel prognostic index. Archives of clinical neuropsychology : the official journal of the National Academy of Neuropsychologists, 22(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acn.2006.08.013 ↵

An experimental design in which one or more independent variables are manipulated by the researcher (as treatments), subjects are randomly assigned to different treatment levels (random assignment), and the results of the treatments on outcomes (dependent variables) are observed

Ability to say that one variable "causes" something to happen to another variable. Very important to assess when thinking about studies that examine causation such as experimental or quasi-experimental designs.

the idea that one event, behavior, or belief will result in the occurrence of another, subsequent event, behavior, or belief

A demonstration that a change occurred after an intervention. An important criterion for establishing causality.

an experimental design in which participants are randomly assigned to control and treatment groups, one group receives an intervention, and both groups receive only a post-test assessment

The measurement error related to how a test is given; the conditions of the testing, including environmental conditions; and acclimation to the test itself

improvements in cognitive assessments due to exposure to the instrument