17.4 Interviews

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Identify key considerations when planning to use interviewing as a strategy for qualitative data gathering, including preparations, tools, and skills to support it

- Assess whether interviewing is an effective approach to gather data for your qualitative research proposal

A common form of qualitative data gathering involves conducting interviews. Interviews offer researchers a way to gather data directly from participants by asking them to share their thoughts on a range of questions related to a research topic. Interviews are generally conducted individually, although occasionally couples (or other dyads, which consist of a combination of two people) may be interviewed. Interviews are a particularly good strategy for capturing unique perspectives and exploring experiences in detail. People may have a host of responses to the request to be interviewed, ranging from flat out rejection to excitement at the opportunity to share their story. As you plan to conduct your interviews you will need to decide on your delivery method, how you will capture the data, you will construct your interview guide, and hone your research interviewing skills.

Delivery method

As technology has advanced, so too have our options for conducting interviews. While in-person interviews are generally still the mainstay of the qualitative researcher, phone or video-based interviews have expanded the reach of many studies, allowing us to gain access to participants across vast distances with relatively few resources. Interviewing in-person allows you to capture important non-verbal and contextual information that will likely be limited if you choose to conduct your interview via phone or video. For instance, if we conduct an interview by phone, we miss the opportunity to see how our participant interacts with their surroundings and we can’t see if their arms are crossed or their foot is fidgety. This may indicate that a certain topic might make them particularly uncomfortable. Alternatively, we may pose a question that makes a smile come across their face. If we are interviewing in person, we can ask a follow-up question noting the smile as a change in their expression, however, it’s hard to hear a smile over the phone! Additionally, there is something to be said for the ability to make a personal connection with your interviewee that may help them to engage more easily in the interview process. This personal connection can be challenging over the phone or mediated by technology. As an example, I often offer to my students that we can meet for “virtual” office hours using Zoom if it is hard for them to get to campus. However, they will often prefer to come to campus, despite the inconvenience because they would prefer to avoid the technology.

Regardless of which method you select, make sure you are well prepared. If you are meeting in person, know where you are going and allow plenty of time to get there. Remember, you are asking someone to give up their time to speak with you, and time is precious! When determining where you will meet for your interview, you may choose to meet at your office, their home, or a neutral setting in the community. If meeting somewhere in the community, do consider that you want to choose a place where you can reasonably assure the participant’s privacy and confidentiality as they are speaking with you. In most instances, I try to ask participants where they would feel most comfortable meeting. If you are speaking over phone or video, make sure to test your equipment ahead of time so that you are comfortable using it, and make sure that both you and the participant have access to a private space as you are speaking. If participants have minor children, plan ahead for whether the children should stay in the same space as the interview. If not, you may need to arrange child care or at least discuss child care with participants in advance. We also want to be mindful of how we are situated during an interview, ideally minimizing any power imbalances. This may be especially important when meeting in an office, making sure to sit across from our participants rather than behind a desk.

Capturing the data

You will also need to consider how you plan to physically capture your data. Some researchers record their interviews, using either a smartphone or a digital recording device. Recording the exchange allows you to have a verbatim record, which can allow the researcher to more fully participate in the interview, instead of worrying about capturing everything in writing. However, if there is a problem with recording – either the quality of the recording or some other equipment malfunction, the researcher can be up the proverbial creek without a paddle. Additionally, using a recording device may be perceived as a barrier between the researcher and the participant, as the participant may not feel comfortable being recorded. If you do plan to record, you should always ask permission first and announce clearly when you are starting and stopping the recording. If you will use recording equipment, be sure to test it carefully in advance, and bring backup batteries/phone charger with you.

The alternative to recording is taking field notes. Field notes consist of a written record of the interview, completed during the interview. You may elect to take field notes even if you are recording the interview, and most people do. This allows us to capture main ideas that stand out to us as researchers, nonverbal information that won’t show up in a recording, and some of our own reactions as the interview is being conducted. These field notes become invaluable if you have a problem with your recording. Even if you don’t, they provide helpful information as you interpret the data you do have in your transcript (the typed version of your recording).

If you are not recording and are relying completely on your notes, it is important to know that you are not going to capture every word and that you shouldn’t try. You want to plan in advance how you will structure your notes so that they make sense to you and are easy to follow. Try to capture all main ideas, important quotes that stand out, and whenever possible, use the participant’s own words. We need to recognize that when we paraphrase what the person is stating, we are introducing our ‘spin’ on it – their ideas go through our filter. We likely can’t avoid some of this, but we do want to minimize it as much as possible. Part of how we do this when we are relying on field notes is to take our interview notes and create expanded field notes, ideally within 24 hours of the interview. The longer you wait to expand your field notes, the less reliable they become, as our memory fades quickly! Much like they sound, expanded field notes take our jottings from the interview and expand them, providing more detail regarding the context or meaning of the statements that were captured. Expanded field notes may also contain questions, comments, or reactions that we, as the researcher, may have had to the data, which are usually kept in the margins, rather than in the body of the notes.

| Field Notes | Expanded Field Notes |

| Q 4

[Long pause] [Soft] “I was scared” (wow—fear 1st emotion) -provider -no purpose -feel lost/empty -losing house -losing family |

After asking question #4 about the participant’s reaction after he lost his job, there was a long pause in our conversation.

When he started speaking again his tone change dramatically. He was joking around a lot before this, but afterward, he became more subdued and spoke softly, breaking direct eye contact with me to stare at the floor during this part fo the conversation. He stated, “I was scared”. (I was really surprised that this was the first thing he mentioned. Previously when we had touched on job loss, he mostly expressed anger or laughed it off, but this felt very different. I’m glad this question was a bit later in the interview.) When I followed up by asking what he was scared of, he mentioned a number of things, including that he would not be able to provide for his family, that he wouldn’t have a sense of purpose and that his work was an important part of who he is. He also described feeling lost and “empty”. Additionally, he feared if this went on that he might lose his house and even his family. He feared this would change how his family saw him. |

Below are a few resources to learn more about taking quality field notes. Along with the reading, practice, practice, practice!

Resources to learn more about capturing your Field Notes:

Deggs, D., & Hernandez, F. (2018). Enhancing the value of qualitative field notes through purposeful reflection.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (2008). Qualitative guidelines project: Fieldnotes.

University of Southern California Libraries. (2019). Research guides: Organizing your social sciences research paper, writing field notes.

Wolfinger, N. (2002). On writing fieldnotes: Collection strategies and background expectancies.

Interview guide

The questions that you ask during your interview will be outlined in a tool called an interview guide. Along with your interview questions, your interview guide will also often contain a brief introduction reminding the participant of the topics that will be covered in the interview and any other instructions you want to provide them (note: much of this will simply serve as a reminder of what you already went over in your informed consent, but it is good practice to remind them right before you get started as well). In addition, the guide often ends with a debriefing statement that thanks the participant for their contribution, inquires whether they have any questions or concerns, and provides contact and resource information as appropriate. Below is a brief interview guide for a study that I was involved with, in which we were interviewing alumni regarding their perceptions of advanced educational needs in the field of social work and specifically their thoughts about practice doctorate of social work (DSW) degrees/programs.

| Introduction

Thank you for taking the time to speak with me today. As a reminder, we are conducting a study to examine your thoughts and perceptions about advanced educational needs in our field and specifically about social work practice doctorate degrees (DSW). We can stop at any time and your participation is completely voluntary. If you need anything explained more clearly as we are going through the questions, please don’t hesitate to ask. Before we get started, I will ask you to complete a brief demographic survey. [pause while participant completes demographic survey] Do you have any questions before we get started?

Interview Guide Questions

Debriefing We are so grateful that you shared your thoughts with us. We will analyze what you shared with us, along with other participants to look for themes and commonalities to help us better understand advanced educational needs in our field and also to help us as we consider developing our own DSW degree at this institution As a reminder, if you have any questions, concerns or you would like to receive copy of the results of our findings, you can contact us at XXX. |

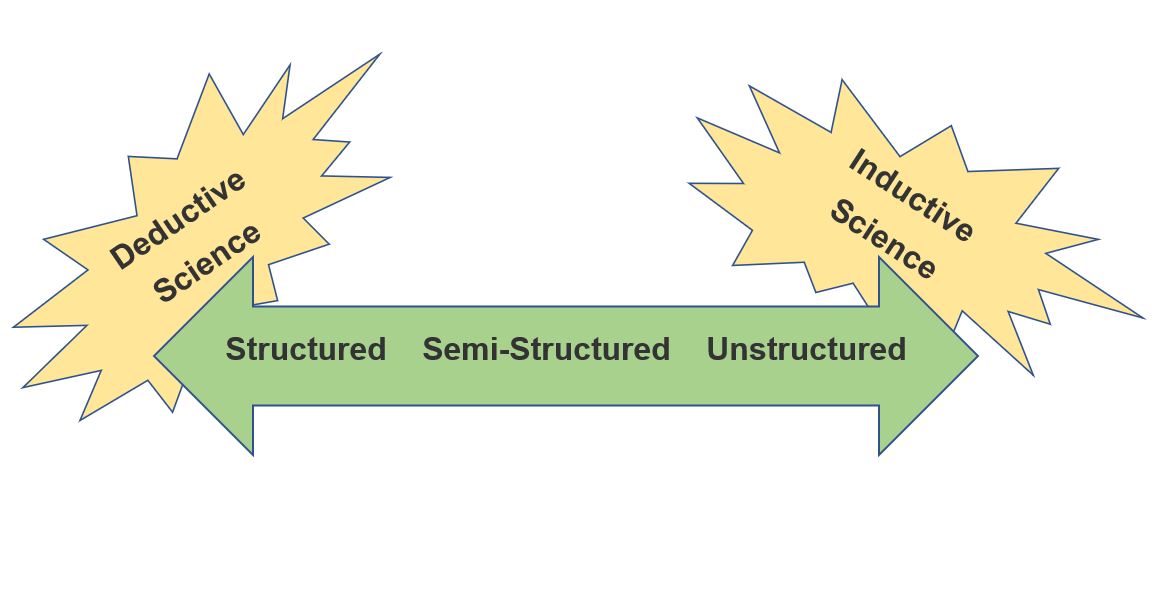

Some interviews are prescribed or structured, with a rigid set of questions that are asked consistently each time, with little to no deviation. This is called a structured interview. More often however, we are dealing with semi-structured interviews, which provide a general framework for the questions that will be asked, but- contain more flexibility to pursue related topics that are brought up by participants. This often leads to researchers asking unplanned follow-up questions to help explore new ideas that are introduced by participants. Sometimes we also use unstructured interviews. These interview guides usually just contain a very open-ended talking prompt that we want participants to respond to. If we are using a highly structured interview guide, this suggests we are leaning toward deductive reasoning apporach—we have a pretty good idea based on existing evidence what we are looking for and what questions we want to ask to help us test our existing understanding. If we are using an unstructured guide, this suggests we are leaning toward an inductive reasoning approach—we start by trying to get people to elaborate extensively on open-ended questions to provide us with data that we will use to develop our understanding of this topic.

An important concept related to the contents of your interview guide is the idea of emergent design. With qualitative research we often treat our interview guide as dynamic, meaning that as new ideas are brought up, we may integrate these new questions into our interview guide for future interviews. This reflects emergent design, as our interview guide shifts to accommodate our emerging understanding of the research topic as we are gathering data. If you do plan to use an emergent design approach in your interviews, it is important to acknowledge this in your IRB application. When you submit your application, you will need to provide the IRB with your interview guide so that they have an idea of the questions you will be discussing with participants. While using an emergent approach to some of your questions is generally acceptable (and even expected), these questions still should be clearly relevant and related to what was presented in your IRB application. If you find that you begin diverging into new areas that are substantively different from this, you should consider submitting an IRB addendum that reflects the changes, and it may be a good idea to consult with your IRB to see if this is necessary.

Designing interview questions and probes

Making up questions, it sounds easy right? Little kids are running around asking questions all the time! However, what you quickly find when conducting research is that it takes skills, ingenuity and practice to craft good interview questions. If you are conducting an unstructured interview, you will generally have fewer questions and they will be quite broad. Depending on your topic, you might ask questions like:

- Tell me about a time…

- What was it like to…

- What should people understand about…

- What does it mean to…

If your interview is more structured, your questions will be a bit more focused, but with qualitative interviewing, we are still generally trying to get people to open up about their experiences with something, so you will want to design questions that will help them to do this. Probes can be important tools to help us accomplish this. You can think of probes as brief follow-ups that are attached to a particular question that will help you explore a topic a bit further. We usually develop probes either through existing literature or knowledge on a topic, or we might add probes to our interview guide as we begin data collection based on what previous participants tell us. As an example, I’m very interested in research on the concept of wellness. I know that the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has adopted a heuristic tool, The Wheel of Wellness, that outlines eight dimensions of wellness based on research by Swarbrick (2006).[1] When interviewing participants with the broad, unstructured question “What does wellness mean in your life?”, I might use these eight dimensions that are spokes of this wheel (i.e. emotional, spiritual, intellectual, physical, environmental, financial, occupational, and social) as probes to explore if/how these dimensions might be relevant in the lives of these participants. Probes suggest that we are anticipating that certain areas may be relevant to our question.

Here are a few general guidelines to consider when crafting your interview questions.

Make them approachable

We are usually relatively unfamiliar with our participants, at least on a personal level. This can make sitting down for an interview where we might be asking some deep questions a bit awkward and uncomfortable, at least at first. Because of this, we want to craft our questions in such a way that they are not off-putting, inadvertently accusatory or judgmental, or culturally insensitive. To accomplish this, we want to make sure we phrase questions in a neutral tone (e.g. “Tell me what that was like”, as opposed to, “That sounds horrible, what was that like”). To accomplish this, we can shift perspectives and think about what it would be like for us to be asked these questions (especially by a stranger). Pilot testing is especially important here. You should plan in time for this, both conducting pilot testing and incorporating feedback on questions. Pilot testing involves you taking your questions on a dry-run with a few people outside of your sample. You might consider testing these out with peers, colleagues, or friends to get their perspective. You might want to get feedback on:

- Did the question make sense to them?

- Did they know what information you were looking for and how to respond?

- What was it like to be asked that question?

- What suggestions do they have for rephrasing the question (if it wasn’t clear)?

Also, if we are conducting interviews on topics that may be particularly hard for people to talk about, we will likely want to start out with some questions that are easier to address prior to getting into the heavier topics.

Make them relatable

Unlike surveys, where researchers may not be able to explain the meaning of a question, with interviews, we are present to help clarify questions if needed. However, ideally, our questions are as clear as possible from the beginning. This means that we avoid jargon or technical terms, we anticipate areas that might be hard to explain and try to provide some examples or a metaphor that might help get the point across, and we do our homework to relay our questions in an appropriate cultural context. Like the discussion above, pilot testing our questions can be very helpful for ensuring the relatability of our questions, especially with community representatives. When pilot testing, do your best to test questions with a person/people from the same culture and educational level as the future participants. What sounds good in our heads might make little sense to our intended audience.

Make them individually distinct, but collectively comprehensive

Just like when we are developing survey questions, you don’t want to ask more than one question at the same time. This is confusing and hard to respond to for the participant, so make sure you are only asking about one idea in each question. However, when you are thinking about your list of questions, or about your interview guide collectively, ensure that you have comprehensively included all the ideas related to your topic. It’s extremely disheartening for a qualitative researcher that has concluded their interviews to realize there was a really important area that was not included in the guide. To avoid this, make sure to know the literature in your area well and talk to other people who study this area to get their perspective on what topics need to be included. Additional topics may come up when you pilot test your interview questions.

Interview skills

As social workers, we receive much training regarding interviewing and related interpersonal skills. Many of these skills certainly transfer to interviewing for research purposes, such as attending to both verbal and non-verbal communication, active listening, and clarification. However, it is also important to understand how a practice-related interview differs from a research interview.

The most important difference has to do with providing clarity around the purpose of the interview. For a practice-related interview, we are gathering information to help understand our client’s situation and better meet their needs. The interview is a means to provide quality services to our clients, and the emphasis is on the client and resources flowing to them. However, the research interview is ideologically much different. The interview is the means and the end. The purpose of the interview is to help answer the research question, but most often, there is little or limited direct benefit to the participant. The researcher is largely the beneficiary of the exchange, as the participant provides us with data. If the participant does become upset or is negatively affected by their participation, we may help facilitate their connection with appropriate support services to address this, such as counseling or crisis numbers (and indeed, this is our ethical obligation as a competent researcher). However, counseling and treatment is not our responsibility when conducting research interviews and we should be very careful not to confuse it as such. If we do act in this way, it creates the potential for a dual relationship with the interviewee (participant and client) and puts them in a vulnerable situation. Make sure you are clear what your role is in this encounter.

Along with recognizing the focus of your role, here is a checklist of general tips for qualitative interviewing skills:

- Approach the interview in a relaxed, but professional manner

- Be observant of verbal, nonverbal, and contextual information

- Exhibit a non-judgmental stance

- Explain information clearly and check for comprehension

- Demonstrate respect for your participants and be polite

- Utilize much more listening and much less talking

- Check for understanding when you are unclear, rather than making assumptions

- Know your materials and technology (e.g. informed consent, interview guide, recording equipment)

- Be concise, clear and organized as you are taking notes

- Have a structured approach for what you need to cover and redirect if the conversation is losing focus

- Be flexible enough so that the interview does not become impersonal and disengaging due to rigidity of your agenda

Key Takeaways

- Data collection through interviewing requires careful planning for both how we will conduct our interviews (e.g. in person, over the phone, online) and the nature of the interview questions themselves. An interview guide is an important document to develop in planning this.

- Qualitative interviewing uses similar skills to clinical interviewing, but is markedly different. This difference is due in large part to the very different purpose of these two activities.

Exercises

Let’s get some practice!

Thinking about your topic, if you were to use interviewing as an approach for data collection, identify 4 interview questions that you would consider asking about your topic. Make sure these are open-ended questions so that your participants can elaborate on them.

- Interview question 1:

- Interview question 2:

- Interview question 3:

- Interview question 4:

Now pilot these. Ask a peer to read these questions and think about trying to answer them. You aren’t interested in their actual answers, you want feedback about how these questions were.

- Were they understandable and clear?

- Were they potentially culturally insensitive or offensive in any way?

- Are they something that it seems reasonable that someone could answer (especially with a researcher they likely don’t know previously)?

- Are they asked in a way that are likely to get people to elaborate (rather than just give a one-word answer)?

- What suggestions do they have to address all/any of these areas?

Based on your peer feedback, re-write your four questions incorporating their suggestions.

- Revised interview question 1:

- Revised interview question 2:

- Revised interview question 3:

- Revised interview question 4:

Resources for learning more about conducting Qualitative Interviews.

Baker, S. E., & Edwards, R. (2012) National Centre for Research Methods review paper: How many qualitative interviews is enough?

Clifford, S. Duke University Initiative on Survey Methodology at the Social Science Research Institute (n.d.). Tipsheet: Qualitative interviews.

Harvard University Sociology Dept. (n.d.). Strategies for qualitative interviews.

McGrath et al., (2018). Twelve tips for conducting qualitative research interviews.

Oltmann, S. M. (2016). Qualitative interviews: A methodological discussion of the interviewer and respondent contexts.

A few exemplars of studies employing Interview Data:

Ewart‐Boyle, S., Manktelow, R., & McColgan, M. (2015). Social work and the shadow father: Lessons for engaging fathers in Northern Ireland.

Flashman, S. H. (2015). Exploration into pre-clinicians’ views of the use of role-play games in group therapy with adolescents.

Irvin, K. (2016). Maintaining community roots: understanding gentrification through the eyes of long-standing African American residents in West Oakland.

- Swarbrick, M. (2006). A wellness approach. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 29(4), 311. ↵

A form of data gathering where researchers ask individual participants to respond to a series of (mostly open-ended) questions.

A combination of two people or objects

An interview guide is a document that outlines the flow of information during your interview, including a greeting and introduction to orient your participant to the topic, your questions and any probes, and any debriefing statement you might include. If you are part of a research team, your interview guide may also include instructions for the interviewer if certain things are brought up in the interview or as general guidance.

Context is the circumstances surrounding an artifact, event, or experience.

Notes that are taken by the researcher while we are in the field, gathering data.

Expanded field notes represents the field notes that we have taken during data collection after we have had time to sit down and add details to them that we were not able to capture immediately at the point of collection.

A statement at the end of data collection (e.g. at the end of a survey or interview) that generally thanks participants and reminds them what the research was about, what it's purpose is, resources available to them if they need them, and contact information for the researcher if they have questions or concerns.

Interview that uses a very prescribed or structured approach, with a rigid set of questions that are asked very consistently each time, with little to no deviation

An interview that has a general framework for the questions that will be asked, but there is more flexibility to pursue related topics that are brought up by participants than is found in a structured interview approach.

Interviews that contain very open-ended talking prompt that we want participants to respond to, with much flexibility to follow the conversation where it leads.

starts by reading existing theories, then testing hypotheses and revising or confirming the theory

when a researcher starts with a set of observations and then moves from particular experiences to a more general set of propositions about those experiences

Emergent design is the idea that some decision in our research design will be dynamic and change as our understanding of the research question evolves as we go through the research process. This is (often) evident in qualitative research, but rare in quantitative research.

Probes a brief prompts or follow up questions that are used in qualitative interviewing to help draw out additional information on a particular question or idea.

Testing out your research materials in advance on people who are not included as participants in your study.